Clinical Significance of Surgical Intervention to Restore Swallowing Function for Sustained Severe Dysphagia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

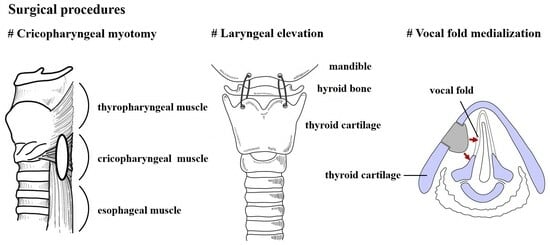

2.2. Surgical Procedure

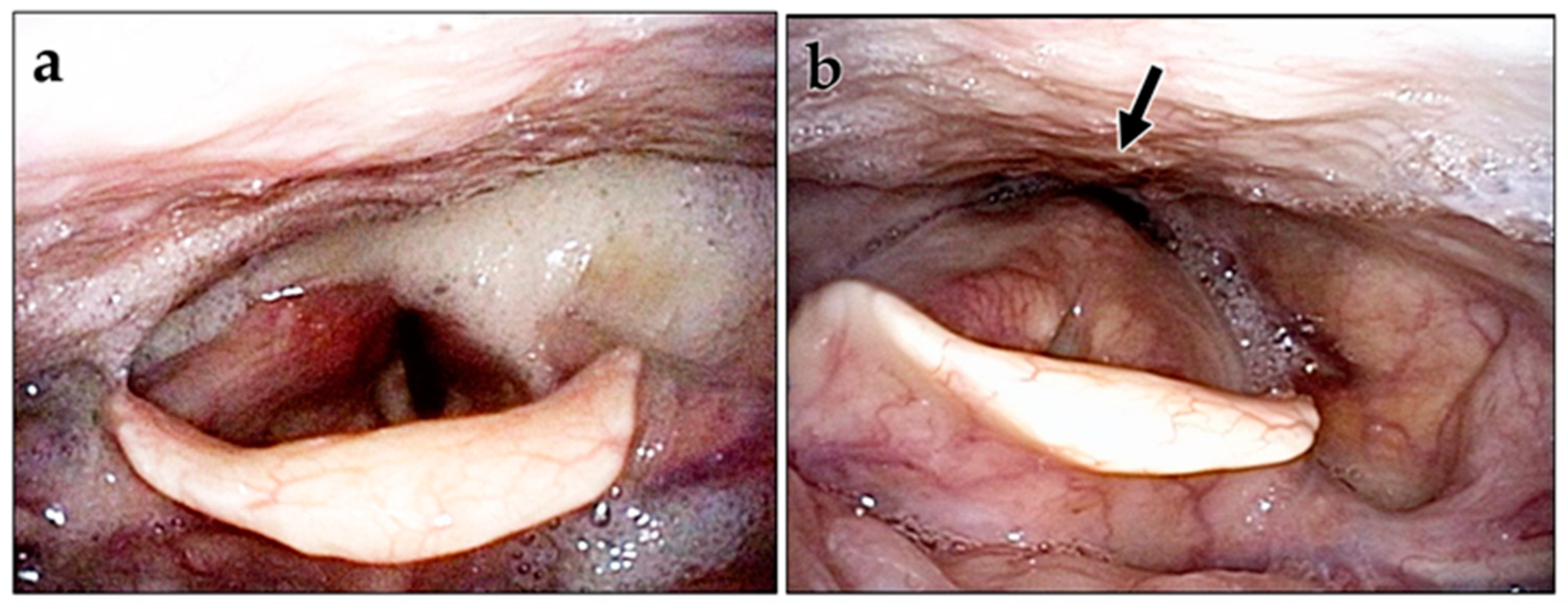

2.2.1. Cricopharyngeal Myotomy

2.2.2. Laryngeal Elevation

2.2.3. Vocal Fold Medialization

2.3. Assessment of Swallowing Function

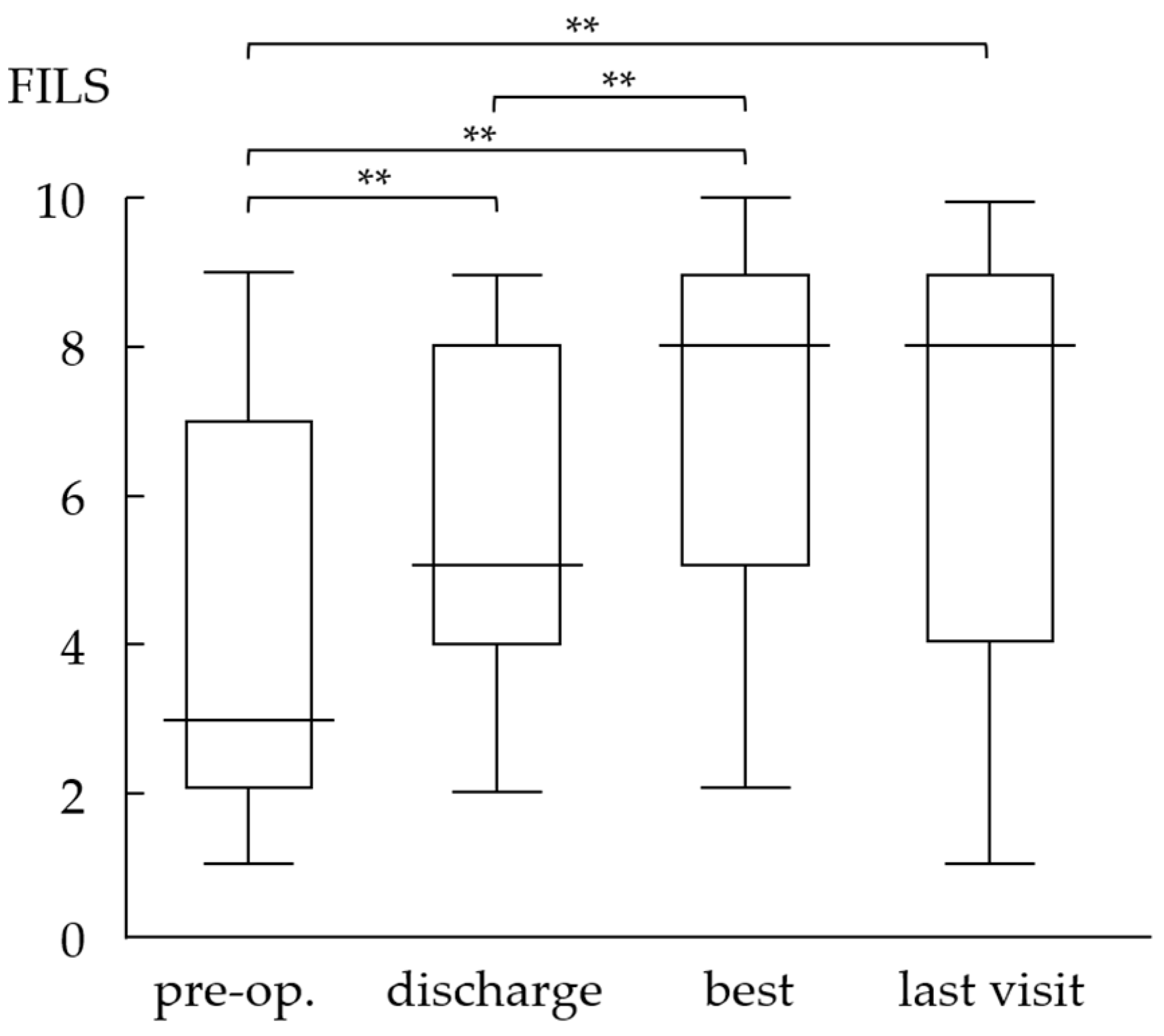

2.3.1. Food Intake Level Scale

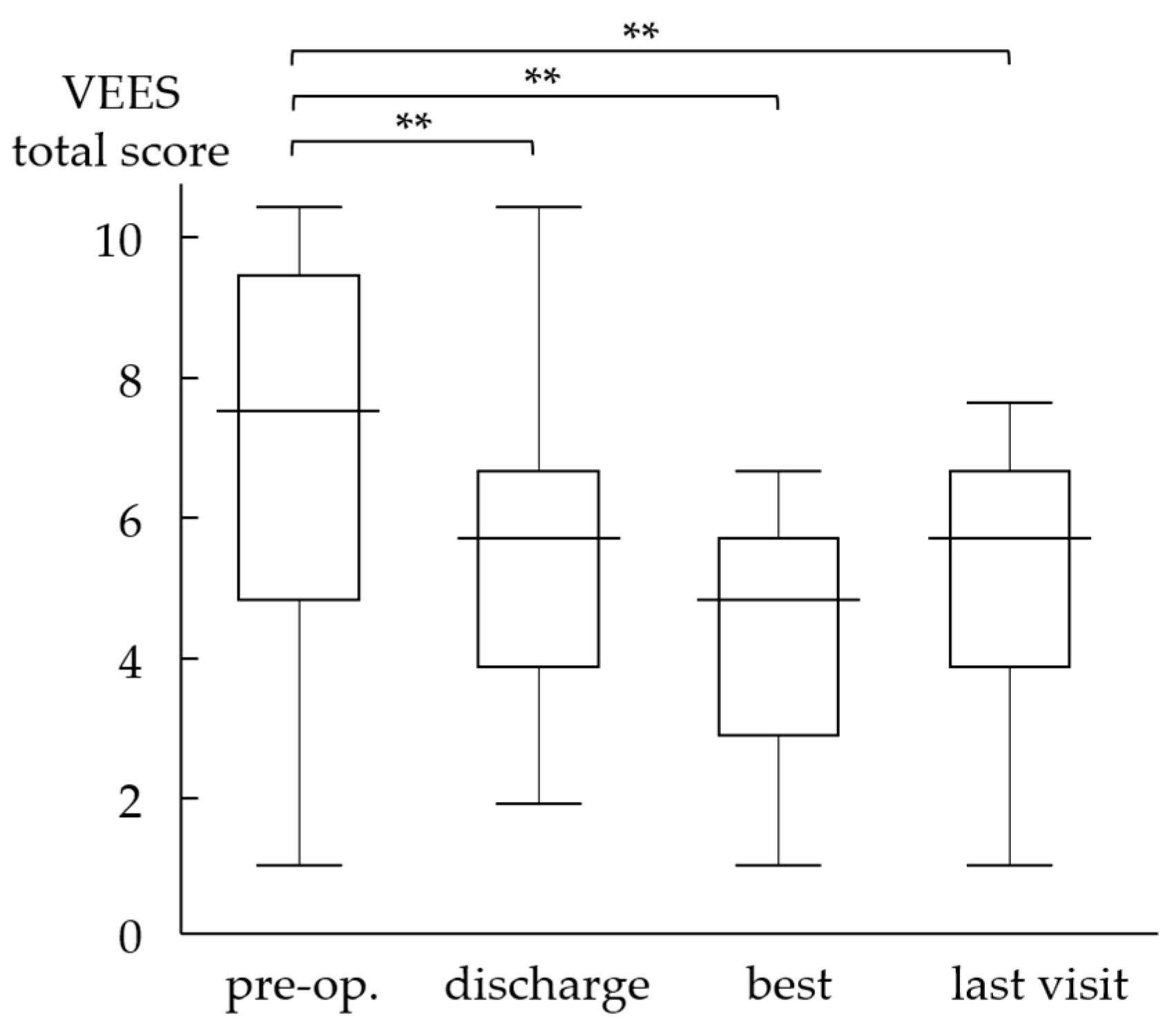

2.3.2. Videoendoscopic Examination Score of Swallowing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Statement

3. Results

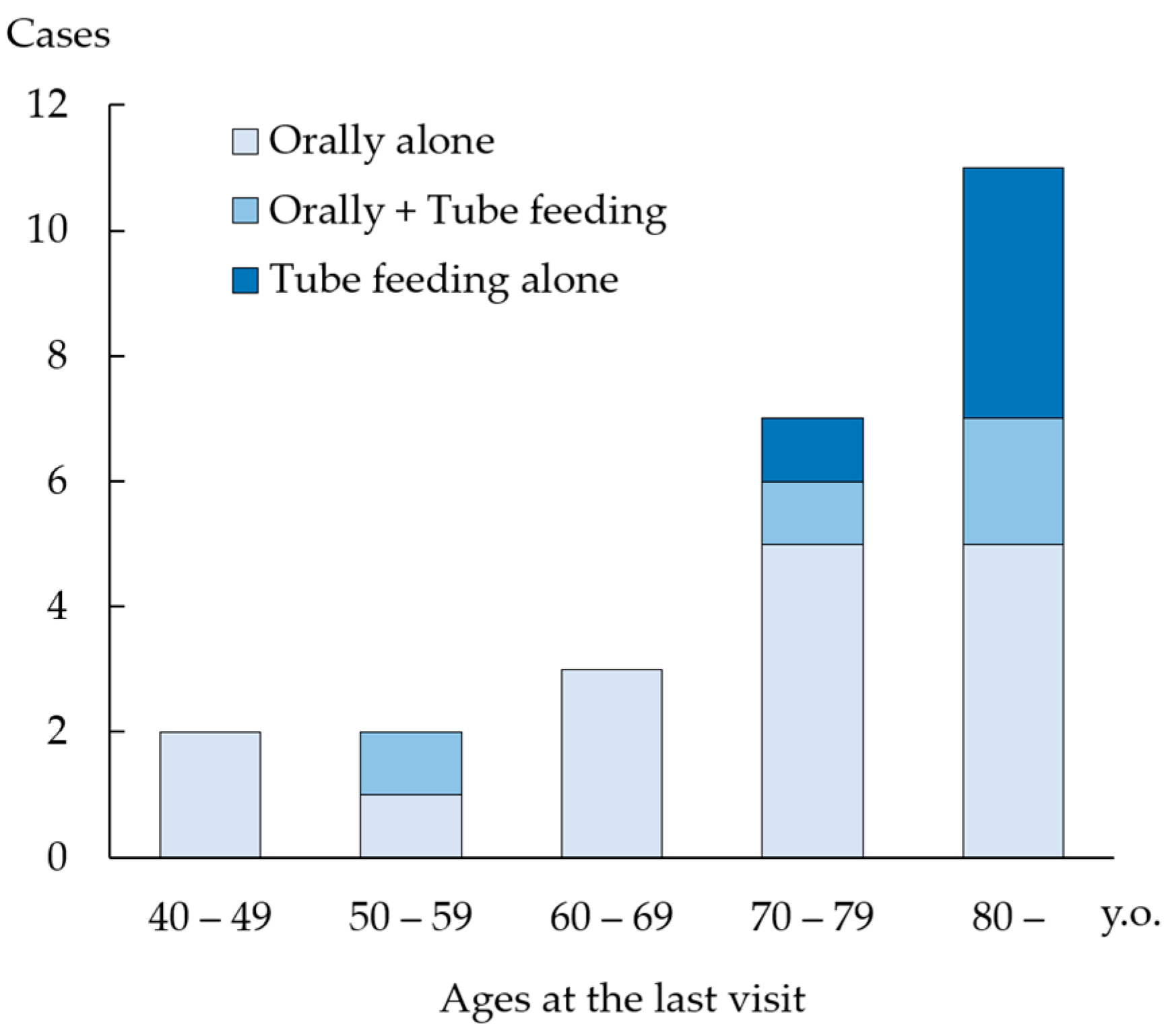

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.2. Evaluation of Oral Intake Ability Using the Food Intake Level Scale

3.3. Videoendoscopic Examination of Swallowing Score

3.4. Investigation of Patients with Stroke

3.5. Postoperative Complications and Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of Surgical Intervention

4.2. Purpose of Surgical Procedures

4.3. Surgical Outcomes

4.4. Surgical Indications

- (1)

- Unsatisfactory improvement in swallowing function despite professional conservative treatments such as rehabilitation.

- (2)

- Stable and non-progressive primary disease.

- (3)

- Dysphagia that is confirmed as primarily a disorder of the pharyngeal swallowing phase.

- (4)

- Patient age ≤ 70 years.

- (5)

- Fairly well-maintained physical and cognitive functions.

- (6)

- Fairly well-maintained pharyngolaryngeal sensation.

- (7)

- Willingness for oral food intake.

- (8)

- Availability of the necessary support at the patient’s home or in a nursing home.

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baijens, L.W.; Clavé, P.; Cras, P.; Ekberg, O.; Forster, A.; Kolb, G.F.; Leners, J.C.; Masiero, S.; Mateos-Nozal, J.; Ortega, O.; et al. European Society for Swallowing Disorders-European Union Geriatric Medicine Society white paper: Oropharyngeal dysphagia as a geriatric syndrome. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1403–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.; Tulunay-Ugur, O.E. Dysphagia in the Older Patient. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 51, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, R.; Dziewas, R.; Beck, A.M.; Clavé, P.; Hamdy, S.; Heppner, H.J.; Langmore, S.; Leischker, A.H.; Martino, R.; Pluschinski, P.; et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older persons-from pathophysiology to adequate intervention: A review and summary of an international expert meeting. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, T.; Ebihara, S.; Mori, T.; Izumi, S.; Ebihara, T. Association between sarcopenia and pneumonia in older people. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, S.; Fukuchi, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Sato, K.; Sekizawa, K.; Matsuse, T.; Japanese Study Group on Aspiration Pulmonary Disease. High incidence of aspiration pneumonia in community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients: A multicenter, prospective study in Japan. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 577–579. [Google Scholar]

- Sura, L.; Madhavan, A.; Carnaby, G.; Crary, M.A. Dysphagia in the elderly: Management and nutritional considerations. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, T.; Tsuda, K.; Takagi, S. Surgical treatment for dysphagia of neuromuscular origin. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 1999, 51, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyodo, M.; Nagao, A.; Tanaka, K. Surgical interventions as a treatment option for severe dysphagia with Intractable aspiration: Concept, indications, and efficacy. Med. Res. Arch. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panebianco, M.; Marchese-Ragona, R.; Masiero, S.; Restivo, D.A. Dysphagia in neurological diseases: A literature review. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 3067–3073. [Google Scholar]

- Hyodo, M.; Aibara, R.; Kawakita, S.; Yumoto, E. Histochemical study of the canine inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle: Implications for its function. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998, 118, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daniero, J.J.; Garrett, C.G.; Francis, D.O. Framework surgery for treatment of unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Curr. Otorhinolaryngol. Rep. 2014, 2, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki, N.; Tanabe, M.; Sawada, M. Arytenoid adduction for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1978, 104, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.J.; Jang, Y.J.; Park, G.Y.; Joo, Y.H.; Im, S. Role of injection laryngoplasty in preventing post-stroke aspiration pneumonia, case series report. Medicine 2020, 99, e19220. [Google Scholar]

- Kunieda, K.; Ohno, T.; Fujishima, I.; Hojo, K.; Morita, T. Reliability and validity of a tool to measure the severity of dysphagia: The Food Intake LEVEL Scale. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013, 46, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyodo, M.; Nishikubo, K.; Hirose, K. New scoring proposed for endoscopic swallowing evaluation and clinical significance. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 2010, 113, 670–678. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, A.; Fujishima, I.; Maeda, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Nishioka, S.; Ohno, T.; Nomoto, A.; Kayashita, J.; Mori, N.; The Japanese Working Group On Sarcopenic Dysphagia. Nutritional Management Enhances the Recovery of Swallowing Ability in Older Patients with Sarcopenic Dysphagia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sugaya, N.; Goto, F.; Seino, Y.; Nishiyama, K.; Okami, K. The effect of laryngeal elevation training on swallowing function in patients with dysphagia. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2021, 135, 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, T.; Horiuchi, A.; Makino, T.; Kajiyama, M.; Tanaka, N.; Hyodo, M. Determination of the cut-off score of an endoscopic scoring method to predict whether elderly patients with dysphagia can eat pureed diets. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 8, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, C.R.; McLean, W.C. Laryngectomy for chronic aspiration. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 1982, 3, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Topf, M.C.; Magaña, L.C.; Salmon, K.; Hamilton, J.; Keane, W.M.; Luginbuhl, A.; Curry, J.M.; Cognetti, D.M.; Boon, M.; Spiegel, J.R. Safety and efficacy of functional laryngectomy for end-stage dysphagia. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman, R.C. Diverting the paralyzed larynx: A reversible procedure for intractable aspiration. Laryngoscope 1975, 85, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, K.; Umezaki, T.; Matsubara, N.; Lee, Y.; Inoguchi, T.; Kikuchi, Y. Tracheoesophageal diversion improves oral uptake of food: A retrospective study. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 277, 2293–2298. [Google Scholar]

- Eibling, D.E.; Snyderman, C.H.; Eibling, C. Laryngotracheal separation for intractable aspiration: A retrospective review of 34 patients. Laryngoscope 1995, 105, 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eisele, D.W.; Yarington, C.T., Jr.; Lindeman, R.C.; Larrabee, W.F., Jr. The tracheoesophageal diversion and laryngotracheal separation procedures for treatment of intractable aspiration. Am. J. Surg. 1989, 157, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, W.W. Surgery to prevent aspiration. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1975, 101, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, S.; Goto, T.; Kabeya, M.; Tayama, N. Surgical closure of the larynx for the treatment of intractable aspiration: Surgical technique and clinical results. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ueha, R.; Magdayao, R.B.; Koyama, M.; Sato, T.; Goto, T.; Yamasoba, T. Aspiration prevention surgeries: A review. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Y.; Kishimoto, S.; Sumi, T.; Uchiyama, M.; Ohno, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Kano, M. Improving the quality of life of patients with severe dysphagia by surgically closing the larynx. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2019, 128, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soga, T.; Suzuki, N.; Kato, K.; Kawamoto-Hirano, A.; Kawauchi, Y.; Izumi, R.; Toyoshima, M.; Mitsuzawa, S.; Shijo, T.; Ikeda, K.; et al. Long-term outcomes after surgery to prevent aspiration for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. Paralysis of deglutition, a post-poliomyelitis complication treated by section of the cricopharyngeus muscle. Ann. Surg. 1951, 133, 572–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, S.; Ekberg, O. Cricopharyngeal myotomy in the treatment of dysphagia. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1990, 15, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, C.; Boon, M.; Spiegel, J. Open vs. endoscopic cricopharyngeal myotomy; Is. there a difference? Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2017, 38, 405–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.S.; Aye, R.W. Endoscopic Approaches to Cricopharyngeal Myotomy and Pyloromyotomy. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2018, 28, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goode, R.L. Laryngeal suspension in head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope 1976, 86, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, K.; Hwang, J.T.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, Y.T.; Park, Y.S.; Park, J.H.; Yoon, K.J. Comparison of methods for evaluation of upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxation duration: Videofluoroscopic swallow study versus high-resolution manometry. Medicine 2022, 101, e30771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, T.I.; Jones, C.A.; Hammer, M.J.; Cock, C.; Dinning, P.; Wiklendt, L.; Costa, M.; McCulloch, T.M. Predicting the activation states of the muscles governing upper esophageal sphincter relaxation and opening. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016, 310, G359–G366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviv, J.E.; Spitzer, J.; Cohen, M.; Ma, G.; Belafsky, P.; Close, L.G. Laryngeal adductor reflex and pharyngeal squeeze as predictors of laryngeal penetration and aspiration. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambayashi, T.; Kato, K.; Ikeda, R.; Suzuki, J.; Honkura, Y.; Hirano-Kawamoto, A.; Ohta, J.; Kagaya, H.; Inoue, M.; Hyodo, M.; et al. Questionnaire survey on pharyngolaryngeal sensation evaluation regarding dysphagia in Japan. Auris Nasus Larynx 2021, 48, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeit, B.; Jung, A.; Ahring, S.; Oelenberg, S.; Muhle, P.; Roderigo, M.; Wenninger, F.; von Itter, J.; Claus, I.; Warnecke, T.; et al. Relationship between post-stroke dysphagia and pharyngeal sensory impairment. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2023, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaee, A.; Murry, T.; Zschommler, A.; Desloge, R.B. Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing in patients with unilateral vocal fold immobility: Incidence and pathophysiology of aspiration. Laryngoscope 2005, 115, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.J. Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006, 14, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No Oral Intake | ||

| Level 1: | No swallowing training #1 is performed except for oral care. | |

| Level 2: | Swallowing training not using food is performed. | |

| Level 3: | Swallowing training using a small quantity of food is performed. | |

| Oral Intake and Alternative Nutrition | ||

| Level 4: | Easy-to-swallow food #2 less than the quantity of a meal (enjoyment level) is ingested orally. | |

| Level 5: | Easy-to-swallow food is orally ingested in one to two meals, but alternative nutrition is also given. | |

| Level 6: | The patient is supported primarily by ingestion of easy-to-swallow food in three meals, but alternative nutrition #3 is used as a complement. | |

| Oral Intake Alone | ||

| Level 7: | Easy-to-swallow food is orally ingested in three meals. No alternative nutrition is given. | |

| Level 8: | The patient eats three meals by excluding food that is particularly difficult to swallow #4. | |

| Level 9: | There is no dietary restriction, and the patient ingests three meals orally, but medical considerations #5 are given. | |

| Level 10: | There is no dietary restriction, and the patient ingests three meals orally (normal). | |

| (A) Salivary pooling in the vallecula and piriform sinuses | |

| Score 1 | No pooling. |

| 2 | Mild pooling. |

| 3 | Moderate pooling to fill the piriform sinus, but penetrate into the larynx. |

| 4 | Severe pooling to overflow into the larynx during inspiration. |

| (B) Elicitability of glottal closure reflex or cough reflex | |

| Score 1 | Easily elicited by a soft touch on the epiglottis. |

| 2 | Elicited by touches on the epiglottis but weak. |

| 3 | Sometimes not elicited by touches on the epiglottis, elicited by touches on the arytenoid. |

| 4 | Very poorly elicited. |

| (C) Provocation of swallowing reflex | |

| Score 1 | Only slight pharyngeal inflow of dyed water can be observed before white-out #1. |

| 2 | Dyed water can be observed to flow to the vallecula. |

| 3 | Dyed water can be observed to flow into the piriform sinus. |

| 4 | Swallowing reflex hardly occurs for a while after dyed water flows into the piriform sinus. |

| (D) Pharyngeal clearance after 3 mL of dyed water swallowed | |

| Score 1 | No residue. |

| 2 | Mild residue, can be cleared by a few additional swallowing. |

| 3 | Moderate residue, cannot be cleared by a few additional swallowing. |

| 4 | Severe residue with considerable aspiration into the larynx. |

| (n = 25) | |

|---|---|

| Age (y.o.) | 43–87 (mean: 70.4) |

| Male/Female | 20:5 |

| Postoperative follow-up (months) | 2–129 (median: 17) |

| Cause of dysphagia: | |

| Cerebrovascular disorder | 16 |

| Aging | 5 |

| Long-term intubation | 1 |

| Pharyngo-esophageal diverticulum | 1 |

| Sarcoidosis cricopharyngeal myopathy | 1 |

| Scleroderma | 1 |

| FILS (pre.) | 1–9 (mean: 4.0) |

| VEES (pre.) | 1–11 (mean: 7.7) |

| Surgical Procedure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cricopharyngeal myotomy | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Laryngeal elevation | ○ | ○ | ||||

| Vocal fold medialization | ○ | |||||

| Pharyngeal constriction | ○ | |||||

| Cervical osteophyte resection | ○ | |||||

| Pharyngo-esophageal diverticulectomy | ○ | |||||

| Infrahyoid myotomy | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| n | 5 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ito, H.; Nagao, A.; Maeda, S.; Nakahira, M.; Hyodo, M. Clinical Significance of Surgical Intervention to Restore Swallowing Function for Sustained Severe Dysphagia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175555

Ito H, Nagao A, Maeda S, Nakahira M, Hyodo M. Clinical Significance of Surgical Intervention to Restore Swallowing Function for Sustained Severe Dysphagia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(17):5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175555

Chicago/Turabian StyleIto, Hiroaki, Asuka Nagao, Suguru Maeda, Maya Nakahira, and Masamitsu Hyodo. 2023. "Clinical Significance of Surgical Intervention to Restore Swallowing Function for Sustained Severe Dysphagia" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 17: 5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175555

APA StyleIto, H., Nagao, A., Maeda, S., Nakahira, M., & Hyodo, M. (2023). Clinical Significance of Surgical Intervention to Restore Swallowing Function for Sustained Severe Dysphagia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(17), 5555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12175555