Gestational Diabetes and Preterm Birth: What Do We Know? Our Experience and Mini-Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

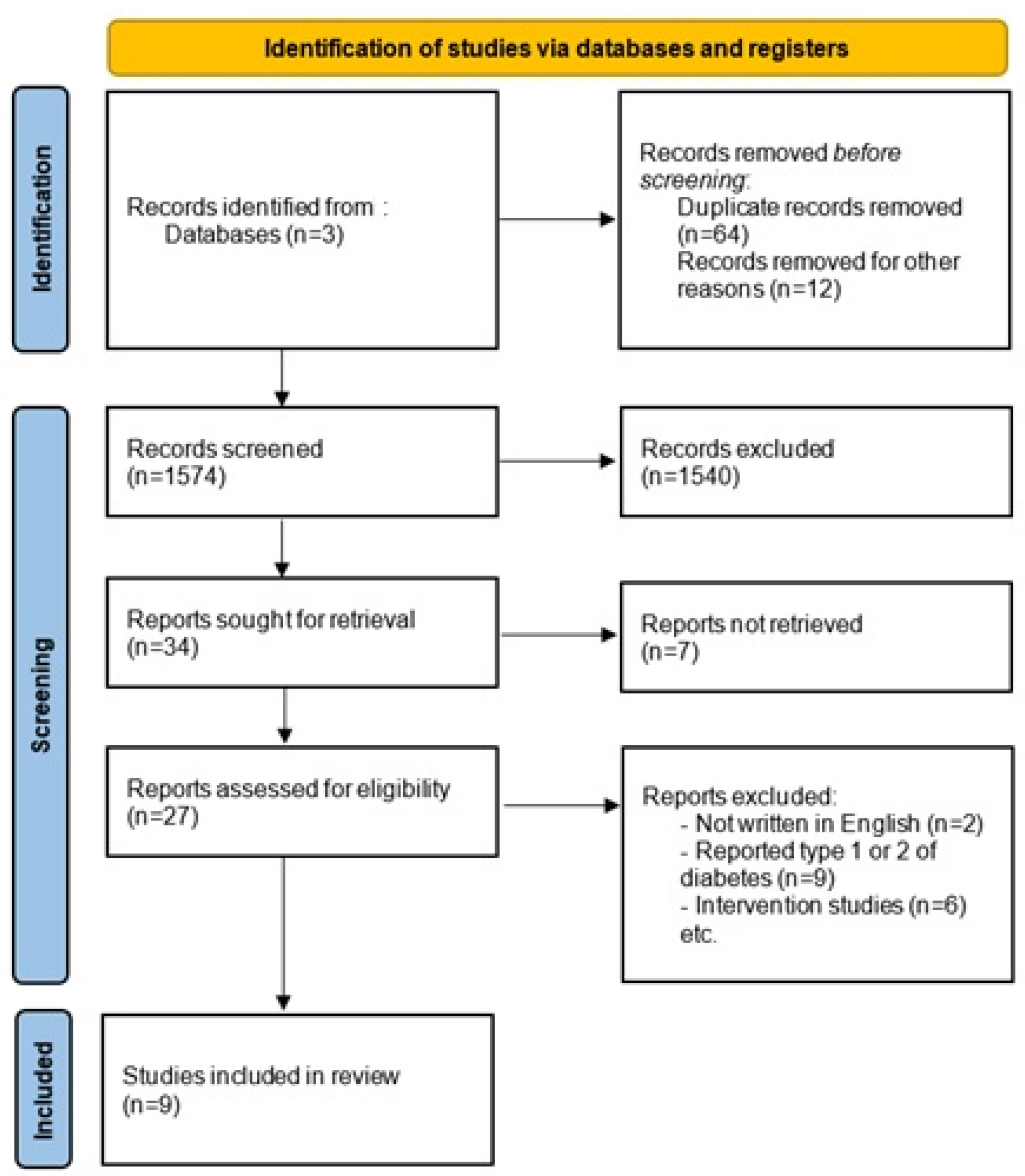

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Sullivan, J.B. Gestational Diabetes: Unsuspected, Asymptomatic Diabetes in Pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1961, 264, 1082–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, J.B.; Mahan, C.M. Criteria for the Oral Glucose Tolerance Test in Pregnancy. Diabetes 1964, 13, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lende, M.; Rijhsinghani, A. Gestational Diabetes: Overview with Emphasis on Medical Management. IJERPH 2020, 17, 9573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwali, S.A.; Onoh, R.C.; Dimejesi, I.B.; Obi, V.O.; Jombo, S.E.; Edenya, O.O. Universal versus Selective Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus among Antenatal Clinic Attendees in Abakaliki: Using the One-Step 75 Gram Oral Glucose Tolerance Test. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Hyperglycaemia First Detected in Pregnancy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Recommendations on the Diagnosis and Classification of Hyperglycemia in Pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, S14–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulletins-Obstetrics, C. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e49–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, A.; Wong, J.; Murphy, H.R.; Ross, G.P. A Clinical Update on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 763–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, B. Humans against Obesity: Who Will Win? Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, E.C.; Denison, F.C.; Norman, J.E.; Reynolds, R.M. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms, Treatment, and Complications. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, P. Future Risk of Diabetes in Mother and Child after Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2009, 104, S25–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, T.A.; Xiang, A.H.; Page, K.A. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Risks and Management during and after Pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, K.; Shakya, S.; Zhang, H. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Macrosomia: A Literature Review. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgal, R.; Gonçalves, E.; Barros, M.; Namora, G.; Magalhães, Â.; Rodrigues, T.; Montenegro, N. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Risk Factor for Non-Elective Cesarean Section: Gestational Diabetes and Cesarean Section. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2012, 38, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, K.E.; Wimsatt, J.H. Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension and Insulin Resistance: Evidence for a Connection. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1999, 78, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.; Luo, C.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, F. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2022, 377, e067946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.R.; Reynolds, R.M. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of Gestational Diabetes and Its Treatment on Fetal Development. Prenat. Diagn. 2020, 40, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutino, G.E.; Tam, C.H.; Ozaki, R.; Yuen, L.Y.; So, W.Y.; Chan, M.H.; Ko, G.T.; Yang, X.; Chan, J.C.; Tam, W.H.; et al. Long-Term Maternal Cardiometabolic Outcomes 22 Years after Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Investig. 2020, 11, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbandi, M.; Rezaeian, S.; Dianatinasab, M.; Yaghoobi, H.; Soltani, M.; Etemad, K.; Valadbeigi, T.; Taherpour, N.; Hajipour, M. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Its Association with Stillbirth, Preterm Birth, Macrosomia, Abortion and Cesarean Delivery among Pregnant Women: A National Prevalence Study of 11 Provinces in Iran. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 62, E885–E891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhkan, A.; Najafi, L.; Malek, M.; Reza Baradaran, H.; Hosseini, R.; Khajavi, A.; Ebrahim Khamseh, M. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Major Risk Factors and Pregnancy-Related Outcomes: A Cohort Study. IJRM 2021, 19, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, S.K.; Das Gupta, R.; Alam, S.; Kaur, K.; Shamim, A.A.; Puthussery, S. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome in South Asia: A Systematic Review. Endocrinol. Diabet. Metab. 2021, 4, e00285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W. The Management of Gestational Diabetes. VHRM 2009, 5, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walani, S.R. Global Burden of Preterm Birth. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrar, S.A.; Hong, P.L. Preeclampsia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Macrosomia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 216. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e18–e35. [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridis, I.; Giouleka, S.; Mamopoulos, A.; Athanasiadis, A.; Dagklis, T. Investigation and Management of Stillbirth: A Descriptive Review of Major Guidelines. J. Perinat. Med. 2022, 50, 796–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.A.; Chambers, B.D.; Baer, R.J.; Ryckman, K.K.; McLemore, M.R.; Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L. Preterm Birth and Nativity among Black Women with Gestational Diabetes in California, 2013–2017: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitzle, L.; Heidemann, C.; Baumert, J.; Kaltheuner, M.; Adamczewski, H.; Icks, A.; Scheidt-Nave, C. Pregnancy Complications in Women with Pregestational and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2023, 120, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhuza, M.P.U.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.; Qi, L.; Chen, D.; Liang, Z. The Association between Maternal HbA1c and Adverse Outcomes in Gestational Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, B.-H.; Guan, H.-M.; Bi, Y.-X.; Ding, B.-J. Gestational Diabetes: Weight Gain during Pregnancy and Its Relationship to Pregnancy Outcomes. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.S.; Moon, H.; Kim, E.H. Risk of Obstetric and Neonatal Morbidity in Gestational Diabetes in a Single Institution: A Retrospective, Observational Study. Medicine 2022, 101, e30777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billionnet, C.; Mitanchez, D.; Weill, A.; Nizard, J.; Alla, F.; Hartemann, A.; Jacqueminet, S. Gestational Diabetes and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes from 716,152 Births in France in 2012. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; Tong, J.; Yin, A.; Wu, L.; Niu, J. Association of Maternal Obesity with Preterm Birth Phenotype and Mediation Effects of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Preeclampsia: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Xing, Y.; Wang, G.; Wu, Q.; Ni, W.; Jiao, N.; Chen, W.; Liu, Q.; Gao, L.; Chao, C.; et al. Does Recurrent Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Increase the Risk of Preterm Birth? A Population-Based Cohort Study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 199, 110628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| General Characteristics of Pregnant Women | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32 ± 4.35 |

| Days of hospitalization | 26 ± 19.91 |

| Preconception BMI (kg/m2) | 26.48 ± 7.93 |

| Gestational age at the moment of birth (weeks) | 33.3 ± 2.58 |

| Emergency C-section | 78% |

| Polyhydramnios | 78% |

| Hypertensive disorders | 50% |

| Insulin treatment | 28.57% |

| Pregnant Women with GDM | At Term Delivery | Preterm Delivery | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 28.9 ± 2.90 | 32.36 ± 4.35 | 0.000313 |

| Days of hospitalization | 4.81 ± 1.52 | 26 ± 19.91 | <0.00001 |

| Preconception BMI (kg/m2) | 23.63 ± 3.64 | 26.48 ± 7.93 | 0.12054 |

| Emergency C-section | 92.3% | 78.57% | 0.12226 |

| Polyhydramnios | 36.92% | 78.57% | 0.004433 |

| Hypertensive disorders | 32.30% | 50% | 0.209362 |

| Insulin treatment | 20% | 28.57% | 0.4816 |

| Study | Year | Number of Patients | C-Section % (n) | Preterm Birth % (n) | Macrosomia % (n) | Preeclampsia % (n) | Stillbirth % (n) | LGA % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darbandi et al. [20] | 2021 | 140 | 46.81% (66) | 57.81% (37) | 8.7% (6) | ND * | 46.10% (65) | ND * |

| Scott et al. [28] | 2020 | 8609 | 49.7% (4278) | 13.33% (1148) | ND * | 12.9% (1114) | ND * | ND * |

| Reitzle et al. [29] | 2023 | 283,210 | 37.6% (106,444) | 7.4% (21,072) | ND * | ND * | 0.22% (635) | 14.4% (40,897) |

| Muhuza et al. [30] | 2023 | 2048 | 27% (553) | 9.62% (194) | 6.74% (138) | ND * | ND * | 3.4% (70) |

| Gou et al. [31] | 2019 | 1523 | 50.23% (765) | 5.06% (77) | 10.57% (161) | 7.09% (108) | ND * | 12.41% (189) |

| Chung et al. [32] | 2022 | 56 | 50% (28) | 28.6% (16) | 1.8% (1) | 3.6% (2) | ND * | 12.5% (7) |

| Billionet et al. [33] | 2017 | 57,629 | 27.8% (16,021) | 8.4% (4841) | 15.7% (9048) | 2.6% (1498) | ND * | ND * |

| Liu et al. [34] | 2022 | 6786 | ND * | 21.46% (594) | ND * | ND * | ND * | ND * |

| Li et al. [35] | 2023 | 16,806 | ND * | 5.18% (870) | ND * | ND * | ND * | ND * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Preda, A.; Iliescu, D.-G.; Comănescu, A.; Zorilă, G.-L.; Vladu, I.M.; Forțofoiu, M.-C.; Țenea-Cojan, T.S.; Preda, S.-D.; Diaconu, I.-D.; Moța, E.; et al. Gestational Diabetes and Preterm Birth: What Do We Know? Our Experience and Mini-Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4572. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144572

Preda A, Iliescu D-G, Comănescu A, Zorilă G-L, Vladu IM, Forțofoiu M-C, Țenea-Cojan TS, Preda S-D, Diaconu I-D, Moța E, et al. Gestational Diabetes and Preterm Birth: What Do We Know? Our Experience and Mini-Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(14):4572. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144572

Chicago/Turabian StylePreda, Agnesa, Dominic-Gabriel Iliescu, Alexandru Comănescu, George-Lucian Zorilă, Ionela Mihaela Vladu, Mircea-Cătălin Forțofoiu, Tiberiu Stefaniță Țenea-Cojan, Silviu-Daniel Preda, Ileana-Diana Diaconu, Eugen Moța, and et al. 2023. "Gestational Diabetes and Preterm Birth: What Do We Know? Our Experience and Mini-Review of the Literature" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 14: 4572. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144572

APA StylePreda, A., Iliescu, D.-G., Comănescu, A., Zorilă, G.-L., Vladu, I. M., Forțofoiu, M.-C., Țenea-Cojan, T. S., Preda, S.-D., Diaconu, I.-D., Moța, E., Gheorghe, I.-O., & Moța, M. (2023). Gestational Diabetes and Preterm Birth: What Do We Know? Our Experience and Mini-Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(14), 4572. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12144572