Awareness and Interest in Uterus Transplantation over Time: Analysis of Those Seeking Surgical Correction for Uterine-Factor Infertility in the US

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

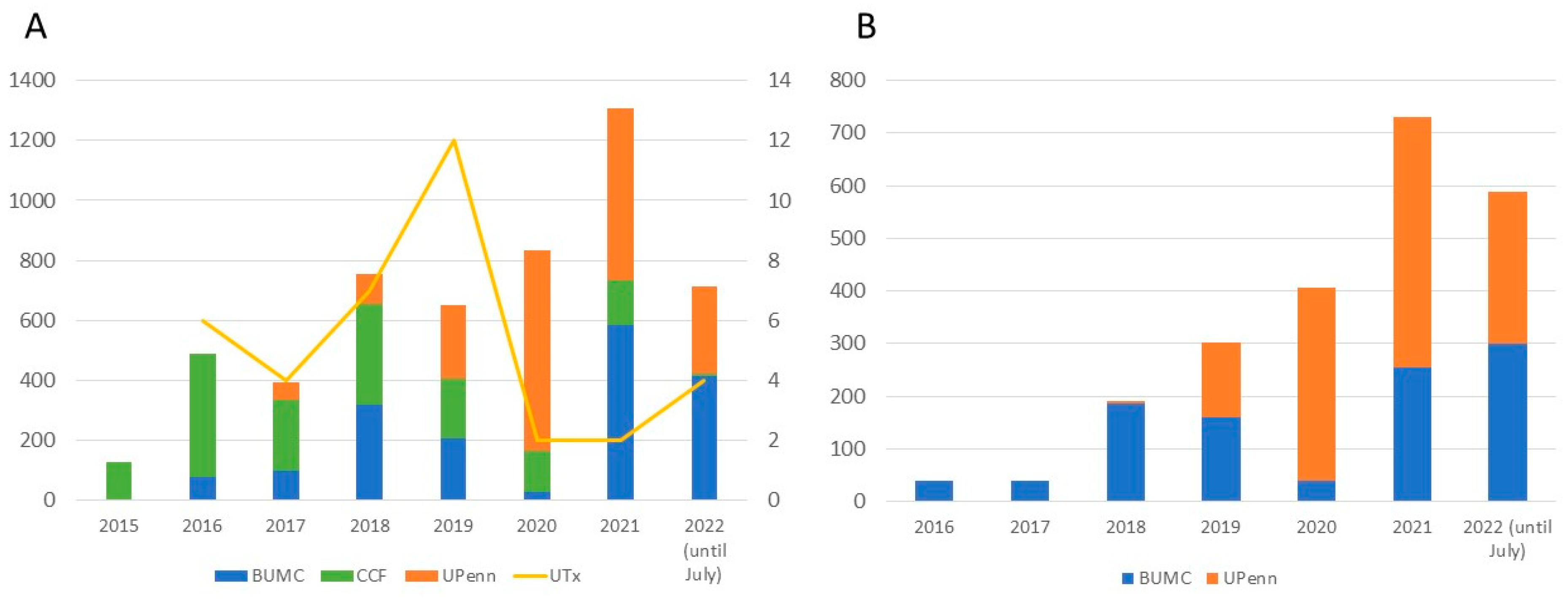

3. Results

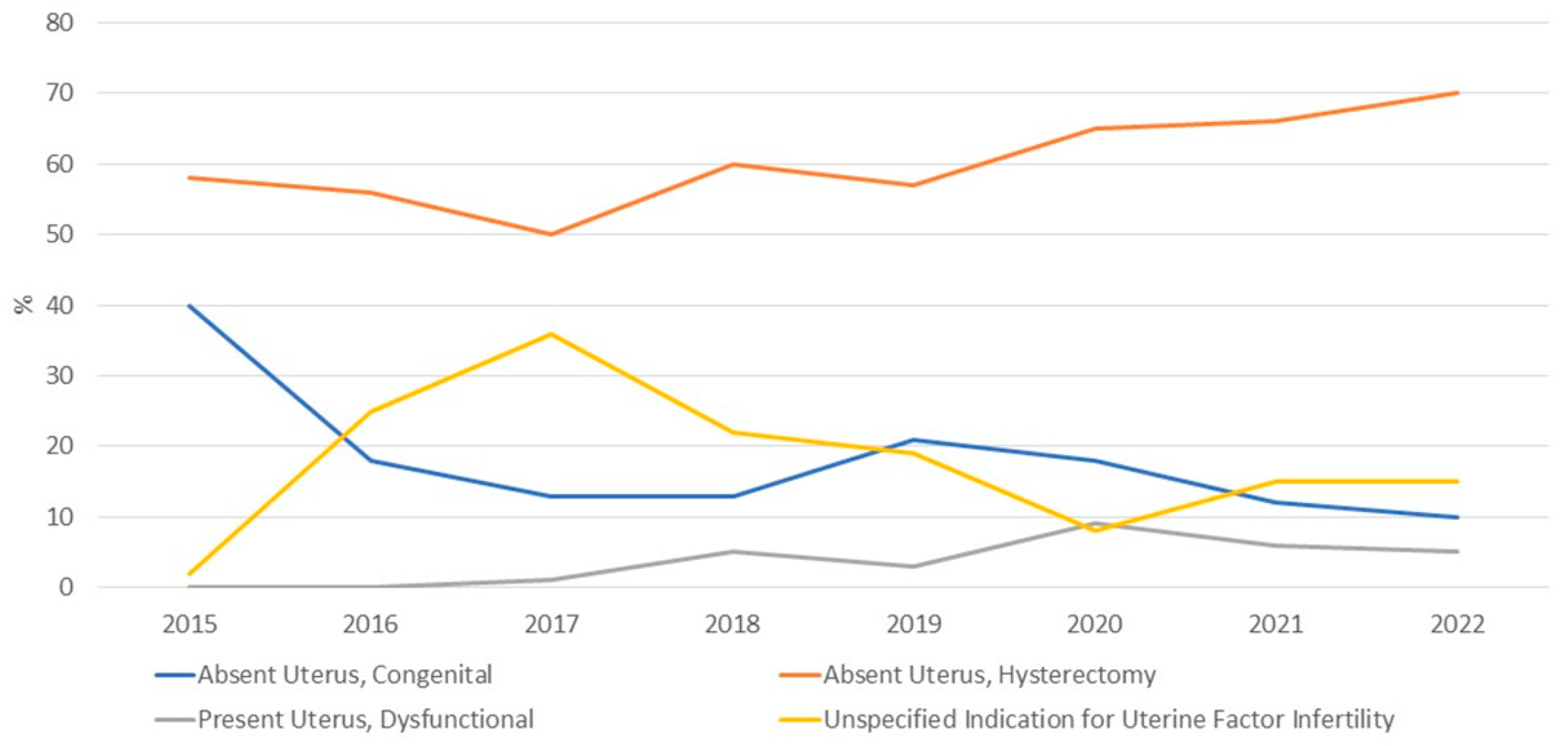

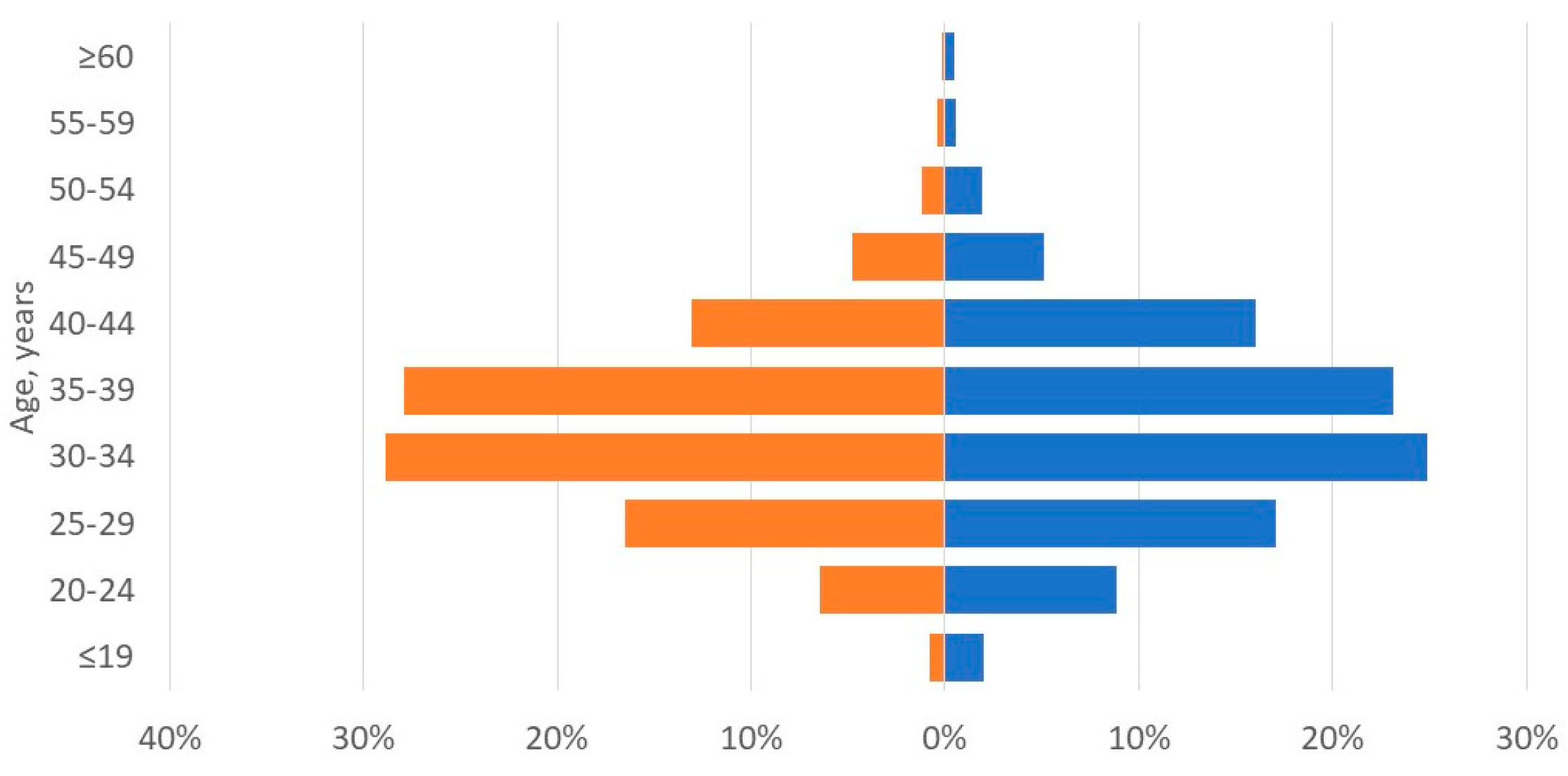

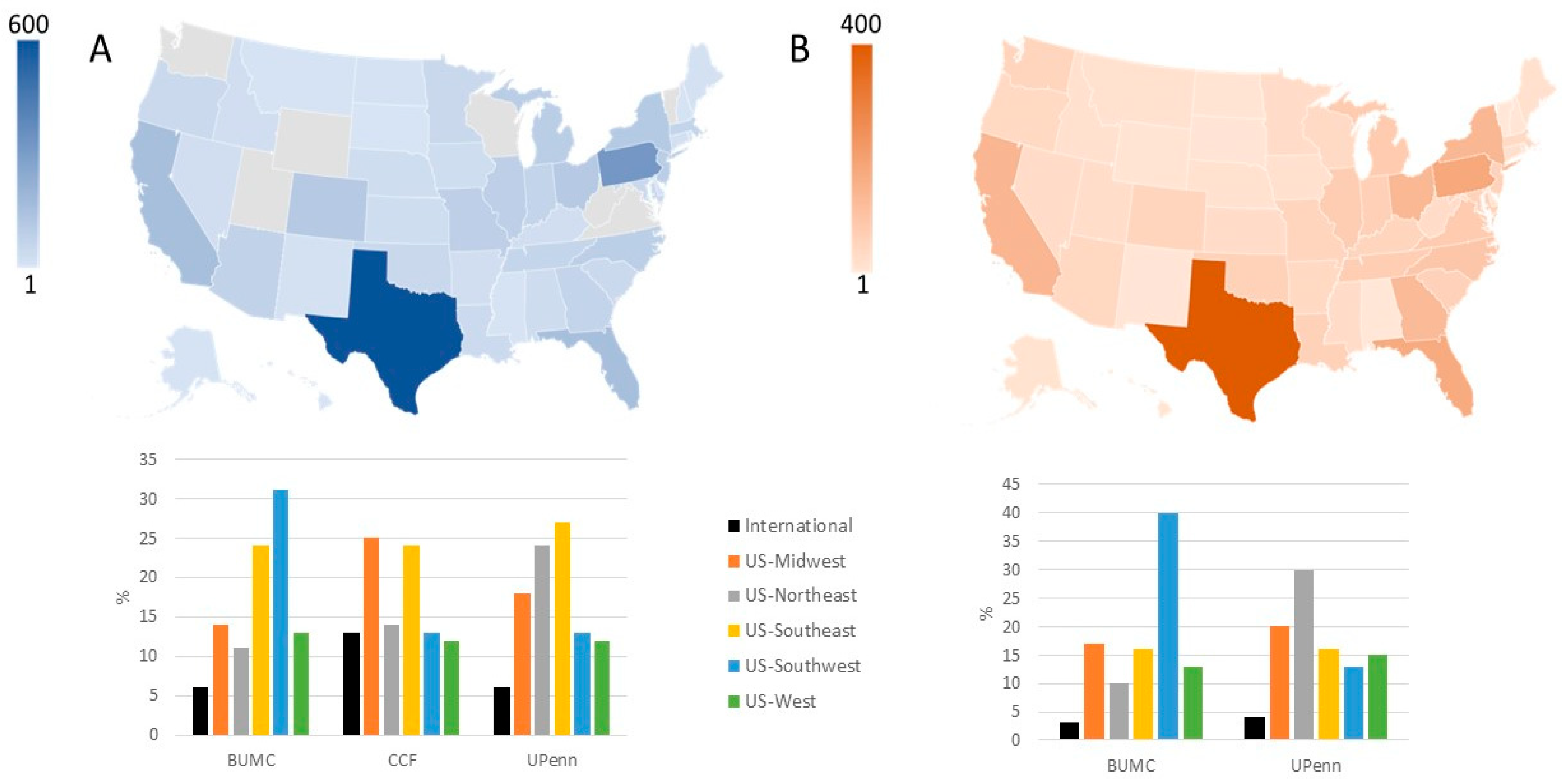

3.1. Applicant Characteristics: Potential Recipients

3.2. Applicant Characteristics: Potential Donors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johannesson, L.; Richards, E.; Reddy, V.; Walter, J.; Olthoff, K.; Quintini, C.; Tzakis, A.; Latif, N.; Porrett, P.; O’Neill, K.; et al. The first 5 years of uterus transplant in the US: A report from the United States Uterus Transplant Consortium. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, G.; McKenna, G.J.; Gunby, R.T., Jr.; Anthony, T.; Koon, E.C.; Warren, A.M.; Putman, J.M.; Zhang, L.; de Prisco, G.; Mitchell, J.M.; et al. First live birth after uterus transplantation in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brännström, M.; Tullius, S.G.; Brucker, S.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Flyckt, R.; Kisu, I.; Andraus, W.; Wei, L.; Carmona, F.; Ayoubi, J.M.; et al. Registry of the International Society of Uterus Transplantation: First report. Transplantation 2023, 107, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arian, S.E.; Flyckt, R.L.; Farrell, R.M.; Falcone, T.; Tzakis, A.G. Characterizing women with interest in uterine transplant clinical trials in the United States: Who seeks information on this experimental treatment? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonnel, M.; Revaux, A.; Menzhulina, E.; Karpel, L.; Snanoudj, R.; Le Guen, M.; De Ziegler, D.; Ayoubi, J.M. Uterus transplantation with live donors: Screening candidates in one French center. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, S.; Tardieu, A.; Filloux, M.; Essig, M.; Pichon, N.; Therme, J.F.; Piver, P.; Aubard, Y.; Ayoubi, J.M.; Garbin, O.; et al. Uterus transplantation in France: For which patients? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 205, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, L.; Wallis, K.; Koon, E.C.; McKenna, G.J.; Anthony, T.; Leffingwell, S.G.; Klintmalm, G.B.; Gunby, R.T., Jr.; Testa, G. Living uterus donation and transplantation: Experience of interest and screening in a single center in the United States. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 331.e1–331.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taran, F.A.; Schöller, D.; Rall, K.; Nadalin, S.; Königsrainer, A.; Henes, M.; Bösmüller, H.; Fend, F.; Nikolaou, K.; Notohamiprodjo, M.; et al. Screening and evaluation of potential recipients and donors for living donor uterus transplantation: Results from a single-center observational study. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, L.; Testa, G.; da Graca, B.; Wall, A. How surgical research gave birth to a new clinical surgical field: A viewpoint from the Dallas Uterus Transplant Study. Eur. Surg. Res. 2023, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, A.M.; McMinn, K.; Testa, G.; Wall, A.; Saracino, G.; Johannesson, L. Motivations and psychological characteristics of nondirected uterus donors from the Dallas UtErus Transplant Study. Prog. Transplant. 2021, 31, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, L.; Santin, G.; Nyangoh Timoh, K.; Boudjema, K.; Jacquot Thierry, L.; Gauthier, T.; Carbonnel, M.; Ayoubi, J.M.; Kerbaul, F.; Lavoue, V. Procurement of uterus in a deceased donor multi-organ donation national program in France: A scarce resource for uterus transplantation? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristek, J.; Johannesson, L.; Testa, G.; Chmel, R.; Olausson, M.; Kvarnström, N.; Karydis, N.; Fronek, J. Limited availability of deceased uterus donors: A transatlantic perspective. Transplantation 2019, 103, 2449–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifferlin, A. First U.S. baby born after a uterus transplant. Time. 1 December 2017. Available online: https://time.com/5044565/exclusive-first-u-s-baby-born-after-a-uterus-transplant/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Park, M. Baby is first to be born in US after uterus transplant, hospital says. CNN. 4 December 2017. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2017/12/04/health/uterus-transplant-us-baby-birth/index.html (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Brännström, M.; Johannesson, L.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Enskog, A.; Mölne, J.; Kvarnström, N.; Diaz-Garcia, C.; Hanafy, A.; Lundmark, C.; Marcickiewicz, J.; et al. First clinical uterus transplantation trial: A six-month report. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, E.H.; Falcone, T.; Flyckt, R.L.; Tzakis, A.G.; Kodish, E.; Richards, E.G. Uterus transplantation: Revisiting the question of deceased donors versus living donors for organ procurement. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, B.; Arora, K.S. Uterus transplantation: The ethics of using deceased versus living donors. Am. J. Bioeth. 2018, 18, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, A.; Edwards, M.; Balayla, J. Ethical considerations in the era of the uterine transplant: An update of the Montreal criteria for the ethical feasibility of uterine transplantation. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, A.; Testa, G. Living donation, listing, and prioritization in uterus transplantation. Am. J. Bioeth. 2018, 18, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayefsky, M.J.; Berkman, B.E. The ethics of allocating uterine transplants. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2016, 25, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A. Allocating uterus transplants—Who gets to be a gestational mother? Am. J. Bioeth. 2018, 18, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, A.; Edwards, M.; Balayla, J. The Montreal criteria for the ethical feasibility of uterine transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2012, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvholm, S.; Enskog, A.; Hammarling, C.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Brännström, M. Uterus transplantation: Joys and frustrations of becoming a ‘complete’ woman—A qualitative study regarding self-image in the 5-year period after transplantation. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, A.E.; Johannesson, L.; Sok, M.; Warren, A.M.; Gordon, E.J.; Testa, G. The journey from infertility to uterus transplantation: A qualitative study of the perspectives of participants in the Dallas Uterus Transplant Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 129, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggan, K.A.; Khan, Z.; Langstraat, C.L.; Allyse, M.A. Provider knowledge and support of uterus transplantation: Surveying multidisciplinary team members. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoletto, P.; Hariton, E.; Farland, L.V.; Goldman, R.H.; Gargiulo, A.R. Uterine transplantation: A survey of perceptions and attitudes of American reproductive endocrinologists and gynecologic surgeons. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylor Scott & White Health. Uterus Transplant Donor Eligibility. Available online: https://www.bswhealth.com/treatments-and-procedures/uterus-transplant (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- PennMedicine. Frequently Asked Questions and Answers about Uterus Transplant. Available online: https://www.pennmedicine.org/for-patients-and-visitors/find-a-program-or-service/transplant-institute/uterus-transplant/faqs-about-uterus-transplant#can-women-donate-their-uterus (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- McCarthy, C.R. Historical background of clinical trials involving women and minorities. Acad. Med. 1994, 69, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.T.; Watkins, L.; Piña, I.L.; Elmer, M.; Akinboboye, O.; Gorham, M.; Jamerson, B.; McCullough, C.; Pierre, C.; Polis, A.B.; et al. Increasing diversity in clinical trials: Overcoming critical barriers. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2019, 44, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Recipients | Living Donors |

|---|---|---|

| Candidates expressing interest, n | 5194 | 2217 |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 34 ± 7 | 34 ± 8 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 29 ± 8 | 28 ± 7 |

| Previous children | 2545 (49%) | 1330 (60%) |

| None | 1039 (20%) | 865 (39%) |

| 1 | 571 (11%) | 244 (11%) |

| 2 | 727 (14%) | 510 (23%) |

| 3 | 676 (13%) | 310 (14%) |

| ≥4 | 571 (11%) | 266 (12%) |

| Not reported | 1610 (31%) | 22 (1%) |

| Geographic origin | ||

| United States | 3999 (77%) | 2128 (96%) |

| International | 312 (6%) | 45 (2%) |

| Not reported | 883 (17%) | 44 (2%) |

| Indication for uterus transplantation | ||

| Absent uterus, congenital | 796 (15%) | NA |

| Absent uterus, hysterectomy | 3259 (63%) | NA |

| Present uterus, dysfunctional | 251 (5%) | NA |

| Not reported | 888 (17%) | NA |

| Category | Indication | N |

|---|---|---|

| Absent Uterus, Congenital | 796 | |

| Mullerian Anomaly (Includes MRKH) | 749 | |

| Swyer Syndrome | 1 | |

| Transgender Female | 41 | |

| Turners Syndrome | 1 | |

| CAIS | 3 | |

| Intersex, no Female Sex Organs | 1 | |

| Absent Uterus, Hysterectomy | 3259 | |

| Gynecological Indication | ||

| Abnormal bleeding | Abnormal bleeding, Unspecified | 58 |

| Menorrhagia | 65 | |

| Endometrial Ablation | 1 | |

| Contraception | Contraception | 8 |

| Complications of contraception * | 21 | |

| Infection | Pelvic inflammatory disease | 5 |

| Infection, Unspecified | 16 | |

| Malformations | Bicornuate Uterus | 2 |

| Hypoplasia | 5 | |

| Outflow Obstruction/Hematometra | 3 | |

| Septate Uterus | 1 | |

| Malformation, Unspecified | 8 | |

| Malignancy or Premalignancy | Cervical dysplasia | 64 |

| Malignancy, Adenosarcoma | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Appendix | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Breast | 1 | |

| Malignancy, Cervical | 120 | |

| Malignancy, Colon | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Endometrial | 56 | |

| Malignancy, Gestational Trophoblastic Disease | 6 | |

| Malignancy, Ovarian | 17 | |

| Malignancy, Placental | 3 | |

| Malignancy, Rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Unspecified | 48 | |

| Pain | Congested Pelvic Syndrome | 9 |

| Chronic Pain | 29 | |

| Dysmenorrhea | 15 | |

| Endometriosis | 298 | |

| Structural Abnormalities | Adenomyosis | 57 |

| Asherman syndrome | 8 | |

| Myomas | 320 | |

| Trauma | Trauma, Sexual | 5 |

| Trauma, Unspecified | 29 | |

| Urogynecological indication | Fistula | 1 |

| Prolapse | 55 | |

| Reconstruction surgery | 1 | |

| Other | Complication of Surgery | 6 |

| Cysts | 23 | |

| Scarring, Unspecified (Includes Complication of Radiation) | 11 | |

| PCOS | 10 | |

| Obstetrical Indication | Abnormal Placentation | 66 |

| Complication of Miscarriage/Abortion | 16 | |

| Complication of Pregnancy, Unspecified | 22 | |

| Complications of Ectopic Pregnancy | 6 | |

| Complications of Molar Pregnancy | 3 | |

| Postpartum Hemorrhage | 289 | |

| Postpartum Infection | 9 | |

| Uterine Rupture at Delivery | 28 | |

| Other | Claim of Malpractice | 33 |

| Family Pressure | 9 | |

| Personal Decision | 3 | |

| Unspecified Indication for Hysterectomy | 1382 | |

| Present Uterus, Dysfunctional | 251 | |

| Adenomyosis | 3 | |

| Asherman Syndrome | 6 | |

| Endometrial Ablation | 19 | |

| Endometriosis | 11 | |

| Hypoplasia | 3 | |

| Malignancy, Unspecified | 4 | |

| Myomas | 14 | |

| Trauma, Unspecified | 4 | |

| Present but Dysfunctional Uterus, Unspecified | 187 | |

| Unspecified Indication for Uterine Factor Infertility | 888 | |

| Total | 5194 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johannesson, L.; Testa, G.; Beshara, M.M.; da Graca, B.; Walter, J.R.; Quintini, C.; Latif, N.; Hashimoto, K.; Richards, E.G.; O’Neill, K. Awareness and Interest in Uterus Transplantation over Time: Analysis of Those Seeking Surgical Correction for Uterine-Factor Infertility in the US. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134201

Johannesson L, Testa G, Beshara MM, da Graca B, Walter JR, Quintini C, Latif N, Hashimoto K, Richards EG, O’Neill K. Awareness and Interest in Uterus Transplantation over Time: Analysis of Those Seeking Surgical Correction for Uterine-Factor Infertility in the US. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(13):4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134201

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohannesson, Liza, Giuliano Testa, Menas M. Beshara, Briget da Graca, Jessica R. Walter, Cristiano Quintini, Nawar Latif, Koji Hashimoto, Elliott G. Richards, and Kathleen O’Neill. 2023. "Awareness and Interest in Uterus Transplantation over Time: Analysis of Those Seeking Surgical Correction for Uterine-Factor Infertility in the US" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 13: 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134201

APA StyleJohannesson, L., Testa, G., Beshara, M. M., da Graca, B., Walter, J. R., Quintini, C., Latif, N., Hashimoto, K., Richards, E. G., & O’Neill, K. (2023). Awareness and Interest in Uterus Transplantation over Time: Analysis of Those Seeking Surgical Correction for Uterine-Factor Infertility in the US. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(13), 4201. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134201