Water-Tight Arthrotomy Joint Closure of Modified Intervastus Approach in Total Knee Arthroplasty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

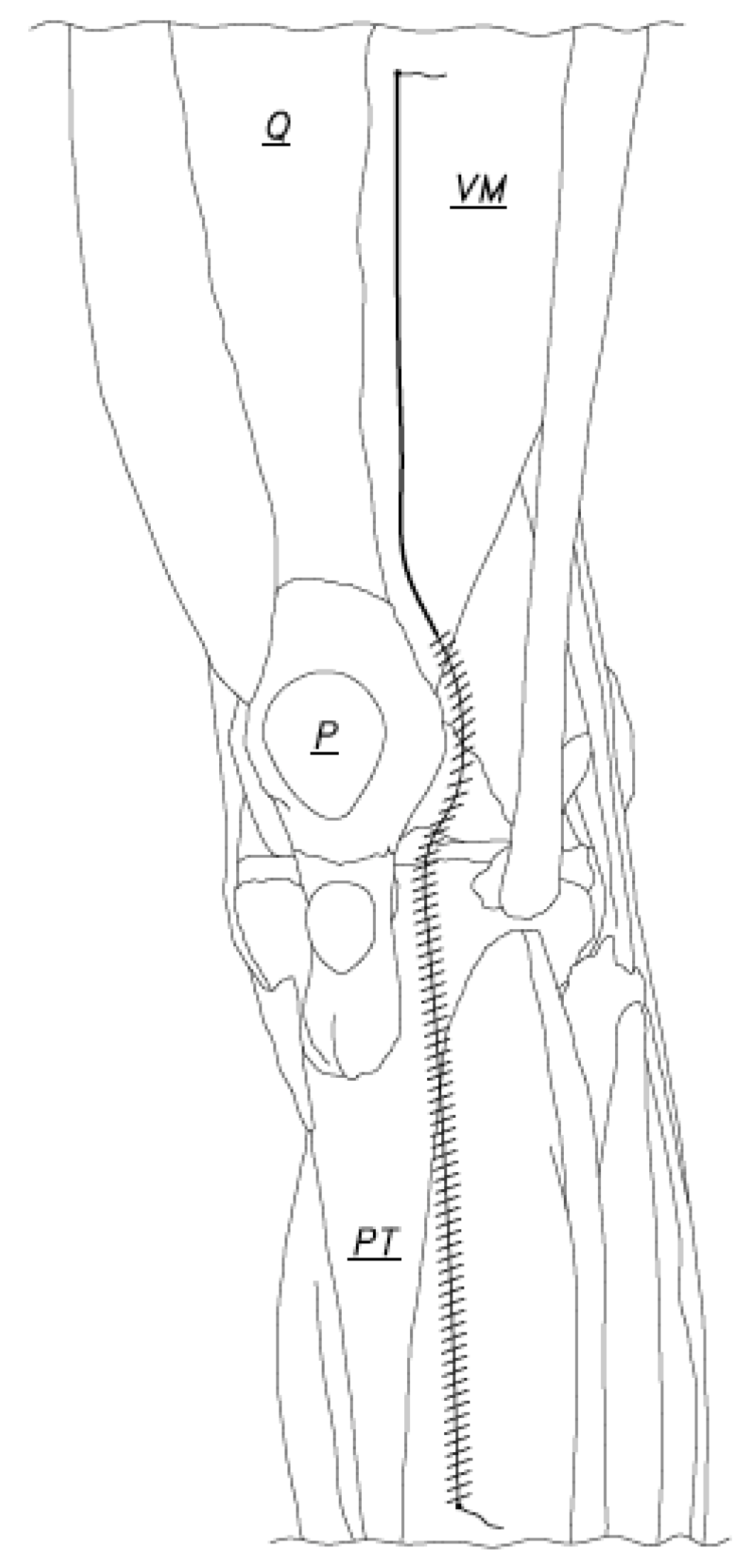

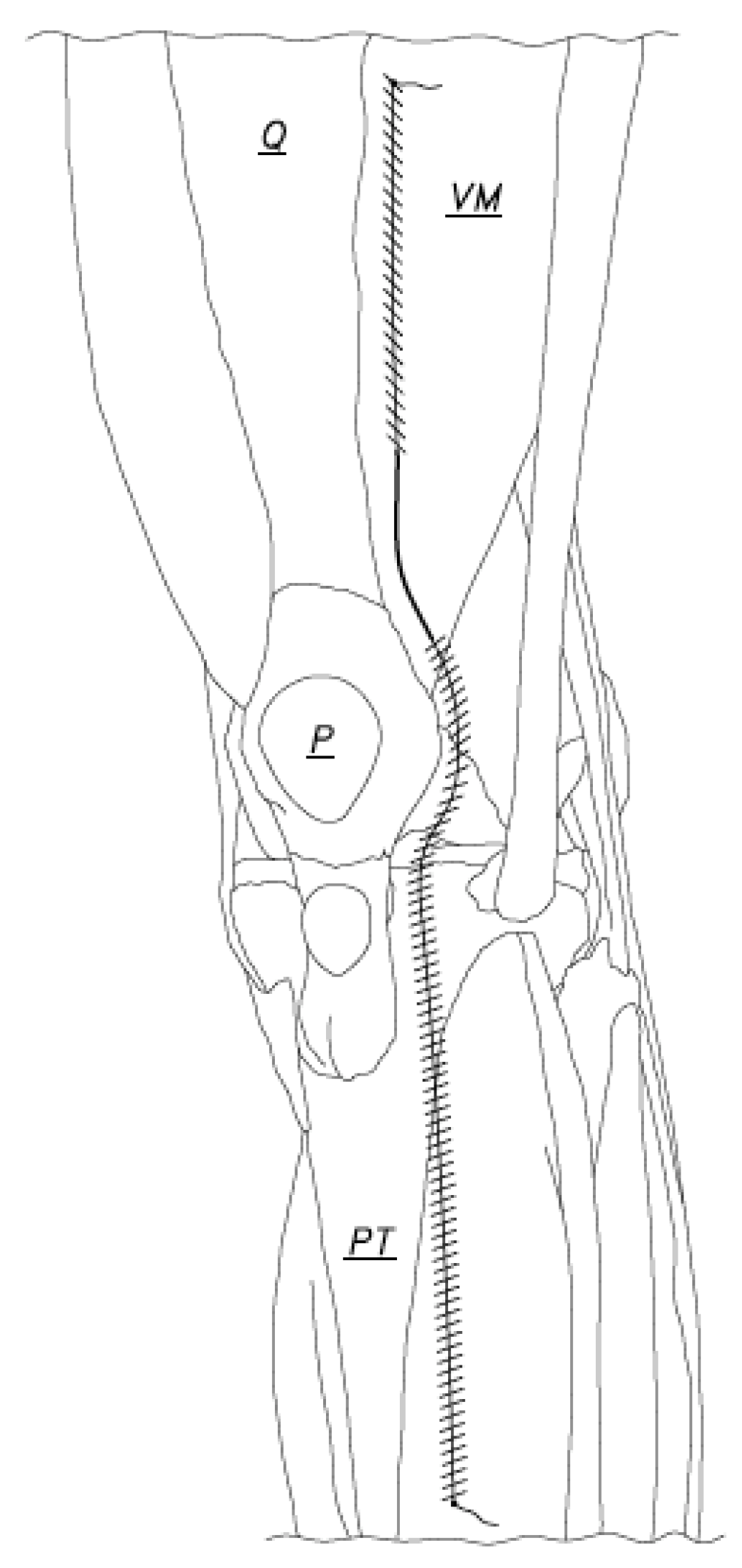

2.2. Water-Tight Arthrotomy Joint Closure Technique

2.3. Outcome Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Infections and Complications

3.2. Operative Time

3.3. Cost

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sartawi, M.M.; Rahman, H.; Kohlmann, J.M.; Levine, B.R. First Reported Series of Outpatient Total Knee Arthroplasty in the Middle East. Arthroplast. Today 2020, 6, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartawi, M.M.; Rahman, H.; Kohlmann, J.M. Clinical and Functional Outcomes Following Modified Intervastus Approach. Tech. Orthop. 2022, 37, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflatooni, J.O.; Wininger, A.E.; Park, K.J.; Incavo, S.J. Alignment options and robotics in total knee arthroplasty. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciola, G.; Bosco, F.; Giustra, F.; Risitano, S.; Capella, M.; Bistolfi, A.; Massè, A.; Sabatini, L. Learning curve in robotic-assisted total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review of the literature. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustra, F.; Bistolfi, A.; Bosco, F.; Fresia, N.; Sabatini, L.; Berchialla, P.; Sciannameo, V.; Massè, A. Highly cross-linked polyethylene versus conventional polyethylene in primary total knee arthroplasty: Comparable clinical and radiological results at a 10-year follow-up. Knee Surg. Sport. Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2023, 31, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, S.; Ruangsomboon, P.; Udomkiat, P.; Unnanuntana, A. Cosmetic outcomes and patient satisfaction compared between staples and subcuticular suture technique for wound closure after primary total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2020, 140, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, P.; Guo, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; He, Z.; Qian, Y. Barbed suture versus traditional suture in primary total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Medicine 2020, 99, e19945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Ni, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, P.; Xu, C.; Chen, J.Y. A Modified Strategy Using Barbed Sutures for Wound Closure in Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Self-Controlled Clinical Trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, D.C.; Keeney, B.J.; Dempsey, B.E.; Koenig, K.M. Are Barbed Sutures Associated With 90-day Reoperation Rates After Primary TKA? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2017, 475, 2655–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wright, R.C.; Gillis, C.T.; Yacoubian, S.V.; Raven, R.B.; Falkinstein, Y.; Yacoubian, S.V. Extensor mechanism repair failure with use of bidirectional barbed suture in total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2012, 27, 1413.e1–1413.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.L.; Patrick, D.A.; Liabaud, B.; Geller, J.A. Superficial wound closure complications with barbed sutures following knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2014, 29, 966–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; DiSegna, S.T.; Shukla, P.Y.; Matzkin, E.G. Barbed versus traditional sutures: Closure time, cost, and wound related outcomes in total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2014, 29, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartawi, M.; Kohlman, J.; Della, V.C. Modified Intervastus Approach to the Knee. J. Knee Surg. 2018, 31, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartawi, M.; Rahman, H.; Kohlmann, J.; Leighton, R.; Kersh, M.E. A Retrospective Analysis of the Modified Intervastus Approach. Am. J. Orthop. 2018, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, C.P.; Maggard-Gibbons, M. Understanding Costs of Care in the Operating Room Time. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, e176233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartawi, M.M.; Rahman, H.; Yousef, I.; Kohlmann, J.M. The Kuwait Stitch: A novel surgical technique for surgical wound closures. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, B.; Jenkinson, R.; O’Heireamhoin, S.; Austin, P.C.; Aktar, S.; Leroux, T.S.; Paterson, M.; Redelmeier, D.A. Surgical duration is associated with an increased risk of periprosthetic infection following total knee arthroplasty: A population-based retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 16, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmallah, R.K.; Khlopas, A.; Faour, M.; Chughtai, M.; Malkani, A.L.; Bonutti, P.M.; Roche, M.; Harwin, S.F.; Mont, M.A. Economic evaluation of different suture closure methods: Barbed versus traditional interrupted sutures. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5 (Suppl. S3), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sartawi, M.M.; Kohlmann, J.M.; Abdelsamie, K.R.; Rahman, H. Water-Tight Arthrotomy Joint Closure of Modified Intervastus Approach in Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12123985

Sartawi MM, Kohlmann JM, Abdelsamie KR, Rahman H. Water-Tight Arthrotomy Joint Closure of Modified Intervastus Approach in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(12):3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12123985

Chicago/Turabian StyleSartawi, Muthana M., James M. Kohlmann, Karam R. Abdelsamie, and Hafizur Rahman. 2023. "Water-Tight Arthrotomy Joint Closure of Modified Intervastus Approach in Total Knee Arthroplasty" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 12: 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12123985

APA StyleSartawi, M. M., Kohlmann, J. M., Abdelsamie, K. R., & Rahman, H. (2023). Water-Tight Arthrotomy Joint Closure of Modified Intervastus Approach in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(12), 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12123985