Prognostic Significance of the PROFUND Index on One Year Mortality in Acute Heart Failure: Results from the RICA Registry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

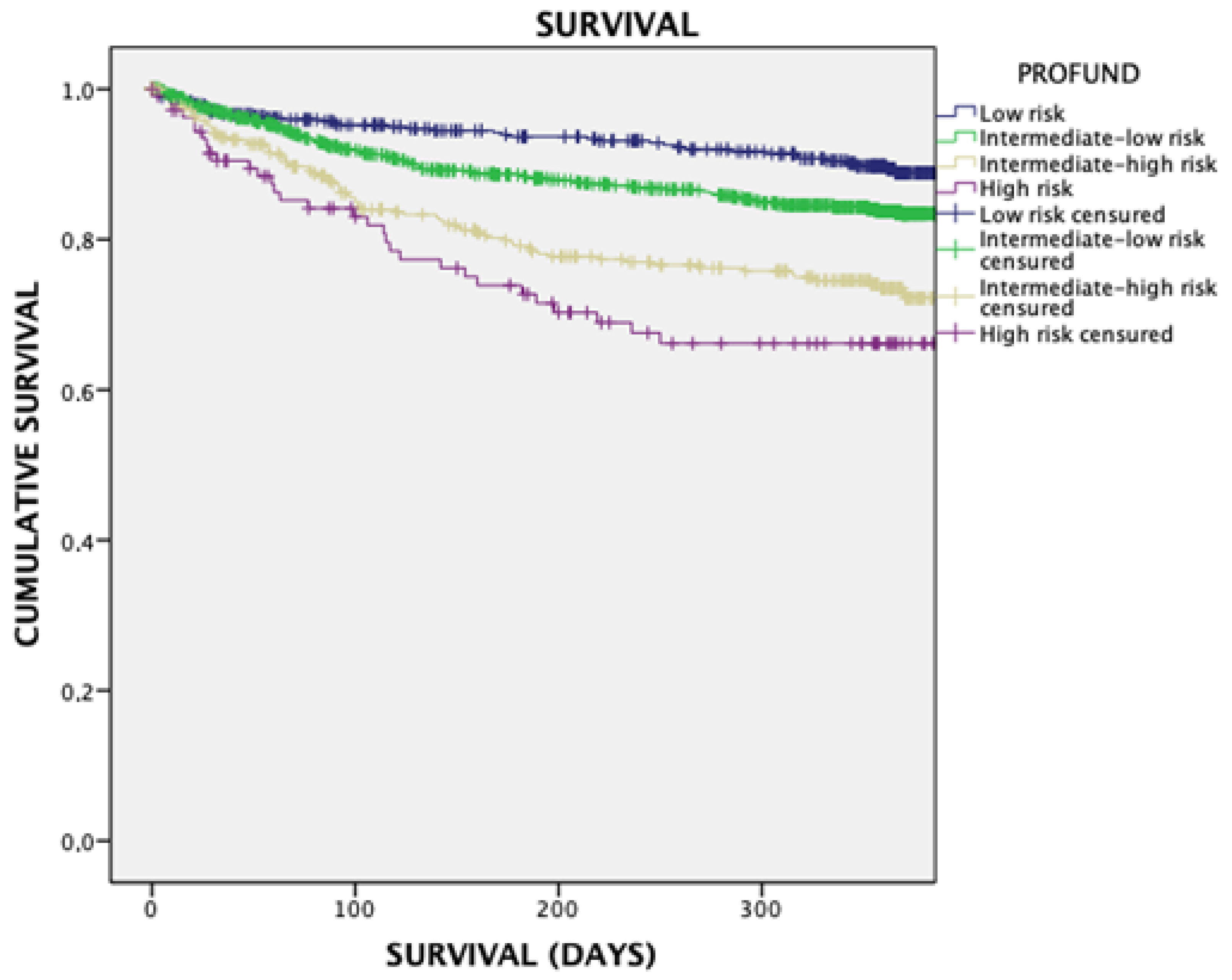

- Low-risk PROFUND group: with values between 0 and 2

- PROFUND group low intermediate risk: with values between 3 and 6

- PROFUND group high intermediate risk 7–10

- High risk PROFUND group with scores greater than or equal to 11

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gassó, M.L.F.; Hernando-Arizaleta, L.; Palomar-Rodríguez, J.A.; Soria-Arcos, F.; Pascual-Figal, D.A. Tendencia y características de las hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca durante periodo 2003–2013. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Martel, A.; Hernández-Meneses, M. Prevalence and prognostic meaning of comorbidity in heart failure. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2016, 216, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Redfield, M.M.; Weston, S.A.; Therneau, T.M.; Hall Long, K.; Shah, N.D.; Roger, V.L. Hospitalizations after heart failure diagnosis a community perspective. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Formiga, F.; Chivite, D.; Conde, A.; Ruiz-Laiglesia, F.; Franco, Á.G.; Bocanegra, C.P.; Manzano, L.; Pérez-Barquero, M.M.; RICA Investigators. Basal functional status predicts three-month mortality after a heart failure hospitalization in elderly patients-the prospective RICA study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 172, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocock, S.J.; Ariti, C.A.; McMurray, J.J.; Maggioni, A.; Køber, L.; Squire, I.B.; Swedberg, K.; Dobson, J.; Poppe, K.K.; Whalley, G.A.; et al. Predicting survival in heart failure: A risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 19, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Ollero-Baturone, M.; Moreno-Gaviño, L.; Barón-Franco, B.; Fuertes, A.; Murcia-Zaragoza, J.; Ramos-Cantos, C.; Alemán, A. Development of a new predictive model for polypathological patients. The PROFUND index. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 22, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Barón-Franco, B.; Nieto-Martín, D.; Moreno-Gaviño, L.; Ramírez-Duque, N.; Ollero-Baturone, M. Prognostic stratification and healthcare approach in patients with multiple pathologies. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2017, 217, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Garrido, M.A.; Martín-Portugués, I.A.; Becerra-Munoz, V.M.; Orellana-Figueroa, H.N.; Sanchez-Lora, F.J.; Morcillo-Hidalgo, L.; Jimenez-Navarro, M.F.; Gomez-Doblas, J.J.; de Teresa-Galvan, E.; Garcia-Pinilla, J.M. Prevalence of comorbidities and the prognostic value of the PROFUND index in a hospital cardiology unit. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2017, 217, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, P.B.; Martín, M.D.N.; de la Pisa, B.P.; Lozano, M.J.G.; Camúñez, M.Á.O.; Wittel, M.B. Validación de un modelo pronóstico para pacientes pluripatológicos en atención primaria. Aten. Primaria 2014, 46, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miró, Ò.; Rossello, X.; Gil, V.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Llorens, P.; Herrero-Puente, P.; Jacob, J.; Bueno, H.; Pocock, S.J.; ICA-SEMES Research Group. Pocock, en nombre del grupo de investigación ICA-SEMES. Predicting 30-Day Mortality for Patients With Acute Heart Failure in the Emergency Department: A Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ather, S.; Chan, W.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Ramasubbu, K.; Zachariah, A.A.; Wehrens, X.H.; Deswal, A. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ling, L.H.; Kistler, P.M.; Kalman, J.M.; Schilling, R.J.; Hunter, R.J. Comorbidity of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016, 13, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Laiglesia, F.J.; Sánchez-Marteles, M.; Pérez-Calvo, J.I.; Formiga, F.; Bartolomé-Satué, J.A.; Armengou-Arxé, A.; Lopez-Quiros, R.; Perez-Silvestre, J.; Serrado-Iglesias, A.; Montero-Pérez-Barquero, M. Comorbidity in heart failure. Results of the Spanish RICA Registry. QJM 2014, 107, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- García-Morillo, J.S.; Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Ollero-Baturone, M.; Aguilar-Guisad, M.; Ramírez-Duque, N.; de la Puente, M.A.G.; Limpo, P.; Romero-Carmona, S.; Cuello-Contreras, J.A. Incidencia y características clínicas de los pacientes con pluripatología ingresados en una unidad de Medicina Interna. Med. Clin. 2005, 125, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Bailón, M.; Iguarán-Bermúdez, R.; López-García, L.; Sánchez-Sauce, B.; Pérez-Mateos, P.; Barrado-Cuchillo, J.; Villar-Martínez, M.; Fernández-Castelao, S.; García-Klepzig, J.L.; Fuentes-Ferrer, M.E.; et al. Prognostic Value of the PROFUND Index for 30-Day Mortality in Acute Heart Failure. Medicina 2021, 57, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PROFUND Index | |

|---|---|

| VARIABLE | POINTS |

| age ≥ 85 years | 3 |

| Clinical features | |

| Active neoplasia | 6 |

| Dementia | 3 |

| III-IV NYHA dyspnea or 3–4 mMRC | 3 |

| Delirium during last hospital admission | 3 |

| Hb < 10 g/dL | 3 |

| Socio-familial situation | |

| Barthel index < 60 | 4 |

| Absence of caregiver or other than spouse | 2 |

| ≥4 hospital admissions over the last 12 months | 3 |

| Variable | All (N = 5424) | PROFUND 0–2 (N = 1132) | PROFUND 3–6 (N = 3087) | PROFUND 7–10 (N = 952) | PROFUND = o > 11 (N = 253) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age media (sd) | 79.9 (8.7) | 71.2 (7.3) | 81.4 (7.8) | 83.9 (6.2) | 85.0 (4.9) | <0.001 |

| Sex. men, N (%) | 2670 (47.3) | 729 (58.3) | 1506 (47.4) | 346 (35.8) | 89 (35.2) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension N (%) | 4866 (86.2) | 1022 (81.2) | 2760 (86.9) | 856 (88.6) | 228 (90.1) | <0.001 |

| T2DM N (%) | 2614 (46.3) | 604 (48.3) | 1404 (45.5) | 436 (45.9) | 122 (48.6) | 0.317 |

| COPD N (%) | 1269 (23.4) | 264 (23.4) | 719 (23.3) | 221 (23.3) | 62 (24.5) | 0.980 |

| OSA N (%) | 2223 (41.1) | 331 (29.3) | 1342 (43.5) | 424 (44.6) | 142 (56.1) | <0.001 |

| Renal insufficiency N (%) | 292 (5.4) | 38 (4.3) | 77 (2.5) | 77 (2.5) | 100 (39.5) | <0.001 |

| Dementia N (%) | 960 (17.7) | 68 (6) | 527 (17.1) | 237 (24.9) | 113 (44.8) | <0.001 |

| Barthel (N = 4664) media (SD) | 82.9 (22.4) | 96.3 (7.8) | 89.7 (13.0) | 55.0 (23.8) | 51.5 (26.1) | <0.001 |

| Pfeiffer(N = 4183) media (SD) | 1.60 (2.12) | 0.62 (1.2) | 1.31 (1.7) | 3.02 (2.5) | 4.31 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Familial support N (%) | 5114 (94.3) | 1048 (92.6) | 2941 (95.3) | 892 (93.7) | 230 (91.3) | <0.001 |

| Charlson score media (SD) | 3.04 (2.5) | 2.49 (2.2) | 2.90 (2.4) | 3.64 (2.7) | 5.30 (3.2) | 0.001 |

| NYHA N (%) | ||||||

| I | 417 (8) | 187 (16) | 193 (6.2) | 29 (3) | 3 (1) | <0.001 |

| II | 2969 (55) | 945 (83) | 193 (6.2) | 343 (36) | 46 (18) | <0.001 |

| III | 1876 (35) | - | 1194 (39) | 523 (55) | 188 (74) | <0.001 |

| IV | 162 (3) | - | 95 (3) | 57 (6) | 16 (6) | <0.001 |

| LVEF media (SD) | 51.4 (15.7) | 49.1 (16.4) | 51.3 (15.3) | 55.9 (15.7) | 53.0 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| BMI media (SD) | 29.2 (7.5) | 30.2 (9.4) | 28.9 (7.3) | 28.9 (5.6) | 28.4 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation N (%) | 2886 (53.2) | 534 (47.2) | 1664 (53.9) | 553 (58.1) | 143 (56.5) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic cardiopathy N (%) | 1393 (25.7) | 303 (26.8) | 793 (25.7) | 239 (25.1) | 60 (23.7) | 0.677 |

| Valvulopathy N (%) | 889 (6.4) | 137 (12.1) | 537 (17.4) | 178 (18.7) | 43 (17) | <0.001 |

| Previous HF | 3335 (61.5) | 578 (51.4) | 1913 (62) | 994 (69.8) | 185 (73.1) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory N (%) | ||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) media (SD) | 12.0 (2.0) | 13.0 (1.7) | 12.0 (2.0) | 11.5 (1.9) | 10.5 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) media (SD) | 58.6 (26.4) | 67.3 (27.8) | 53.5 (25.4) | 53.6 (25.4) | 51.3 (26.5) | <0.001 |

| proBNP (N = 2569) pg/mL media | 6686.6 | 5829.4 | 6996.6 | 7500.0 | 8219.0 | 0.131 |

| Albumin (N = 183) (g/L) media/sd | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.2 (0.6) | 3.1 (0.6) | 0.136 |

| Treatment N (%) | ||||||

| Beta blockers N (%) | 36,883 (68.5%) | 837 (74.4%) | 2130 (69.4%) | 561 (59.5%) | 156 (62.8)% | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors N (%) | 2061 (38.3%) | 486 (43.1%) | 1111 (36.7%) | 352 (37.1%) | 98 (39.1%) | 0.001 |

| ARA-2 N (%) | 1464 (27.4%) | 305 (27.3%) | 833 (27.1%) | 266 (28.8%) | 65 (26.1%) | 0.720 |

| Sacubitril valsartan N (%) | 141 (2.6%) | 38 (3.4%) | 86 (2.8%) | 15 (1.6%) | 30 (1.2%) | 0.025 |

| Furosemide (mg) N (%) | 64.3 (41.3) | 61.8 (37.2) | 64.8 (44.5) | 64.6 (35.4) | 68.7 (39.9) | 0.087 |

| Mineralocorticoids N (%) | 1247 (23.1%) | 271 (24%) | 710 (23.4%) | 199 (21.4%) | 53 (21.3%) | 0.447 |

| SGLT2I N (%) | 32 (0.6%) | 12 (1.1%) | 12 (0.4%) | 4 (0.5%) | 303 (1.2%) | 0.020 |

| Ivabradine N (%) | 65 (1.2%) | 19 (1.7%) | 37 (1.2%) | 7 (0.8%) | 101 (0.4%) | 0.171 |

| Anticoagulant N (%) | 2223 (40.6%) | 441 (39.6%) | 1265 (41.5%) | 380 (40.2)% | 88 (35.2%) | 0.189 |

| Mortality at 30 days N (%) | 1611 (29.7) | 217 (19.2) | 866 (28.1) | 405 (42.5) | 123 (48.6) | <0.001 |

| 30 days readmission N (%) | 1226 (22.8) | 193 (17.1) | 646 (21.1) | 290 (30.7) | 97 (38.6) | <0.001 |

| Mortality at 6 months N (%) | 1827 (33.7) | 271 (23.9) | 977 (31.6) | 446 (46.8) | 133 (52.6) | <0.001 |

| 6 months readmission N (%) | 2120 (39.4) | 363 (32.2) | 1154 (37.7) | 469 (49.6) | 134 (53.4) | <0.001 |

| One year mortality N (%) | 3308 61.3% | 645 57.1% | 1821 (59.4) | 647 (68.9) | 189 (74.7) | <0.001 |

| One year mortality N (%) | 1478 (72.5) | 781 (69.4) | 2193 (71.6) | 722 (76.4) | 209 (83.3) | <0.001 |

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | RR (IC al 95%) | p | RR (IC al 95%) | p |

| PROFUND index Intermediate-Low Intermediate-High High Sex (Men) | 1.648 (1.074–2.530) 2.619 (1.583–4.334) 2.525 (1.255–5.081) 1.086 (0.812–1.453) | 0.022 <0.001 <0.001 0.577 | 1.703 (1.115–2.600) 2.712 (1.658–4.435) 2.590 (1.293–5.190) | 0.014 <0.001 <0.01 |

| Charlson score | 1.082 (1.026–1.140) | 0.004 | 1.089 (1.036–1.145) | 0.001 |

| proBNP/1000 pg/mL Gromerular filtration rate | 1.018 (1.000–1.037) 0.997 (0.991–1003) | 0.052 0.370 | 1.019 (1.002–1.037) | 0.03 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 1.003 (0.993–1.013) | 0.513 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Méndez-Bailon, M.; Iguarán-Bermudez, R.; Formiga-Pérez, F.; Arévalo Lorido, J.C.; Suárez-Pedreira, I.; Morales-Rull, J.L.; Serrado-Iglesias, A.; Llacer-Iborra, P.; Ormaechea-Gorricho, G.; Carrasco-Sánchez, F.J.; et al. Prognostic Significance of the PROFUND Index on One Year Mortality in Acute Heart Failure: Results from the RICA Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11071876

Méndez-Bailon M, Iguarán-Bermudez R, Formiga-Pérez F, Arévalo Lorido JC, Suárez-Pedreira I, Morales-Rull JL, Serrado-Iglesias A, Llacer-Iborra P, Ormaechea-Gorricho G, Carrasco-Sánchez FJ, et al. Prognostic Significance of the PROFUND Index on One Year Mortality in Acute Heart Failure: Results from the RICA Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(7):1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11071876

Chicago/Turabian StyleMéndez-Bailon, Manuel, Rosario Iguarán-Bermudez, Francesc Formiga-Pérez, José Carlos Arévalo Lorido, Iván Suárez-Pedreira, Jose Luis Morales-Rull, Ana Serrado-Iglesias, Pau Llacer-Iborra, Gabriela Ormaechea-Gorricho, Francisco Javier Carrasco-Sánchez, and et al. 2022. "Prognostic Significance of the PROFUND Index on One Year Mortality in Acute Heart Failure: Results from the RICA Registry" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 7: 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11071876

APA StyleMéndez-Bailon, M., Iguarán-Bermudez, R., Formiga-Pérez, F., Arévalo Lorido, J. C., Suárez-Pedreira, I., Morales-Rull, J. L., Serrado-Iglesias, A., Llacer-Iborra, P., Ormaechea-Gorricho, G., Carrasco-Sánchez, F. J., Casado-Cerrada, J., Andrès, E., Diez-Manglano, J., Lorenzo-Villalba, N., & Montero-Pérez-Barquero, M. (2022). Prognostic Significance of the PROFUND Index on One Year Mortality in Acute Heart Failure: Results from the RICA Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(7), 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11071876