Intraoperative Appearance of Endosalpingiosis: A Single-Center Experience of Laparoscopic Findings and Systematic Review of Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Own Population

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Systematic Review Population

2.4. Parameters

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Quality Assessment Systematic Review

2.7. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

3.1. Own Population

3.1.1. Demographic Data—Age, Parity, Menopause, Reasons for Surgery

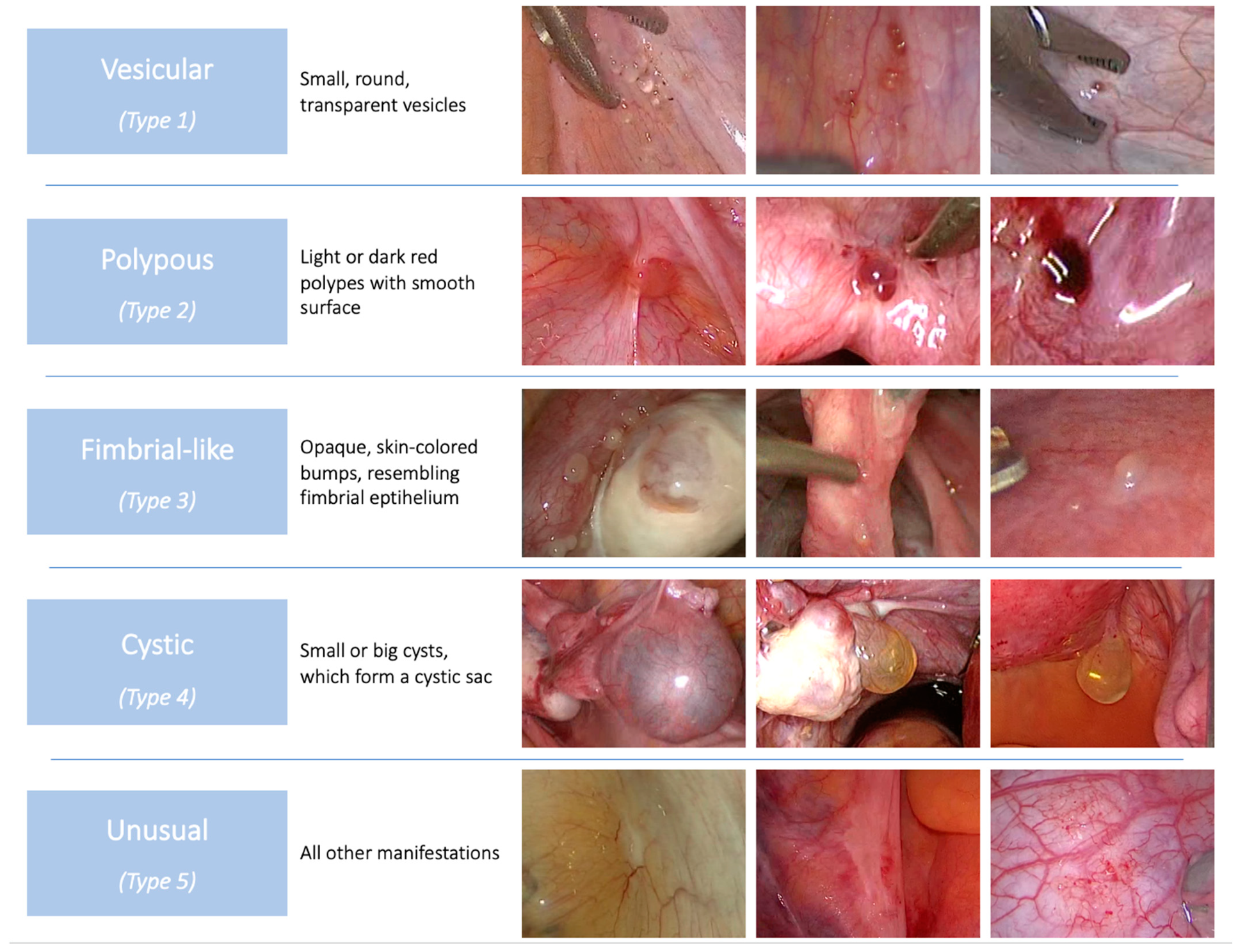

3.1.2. Phenotype

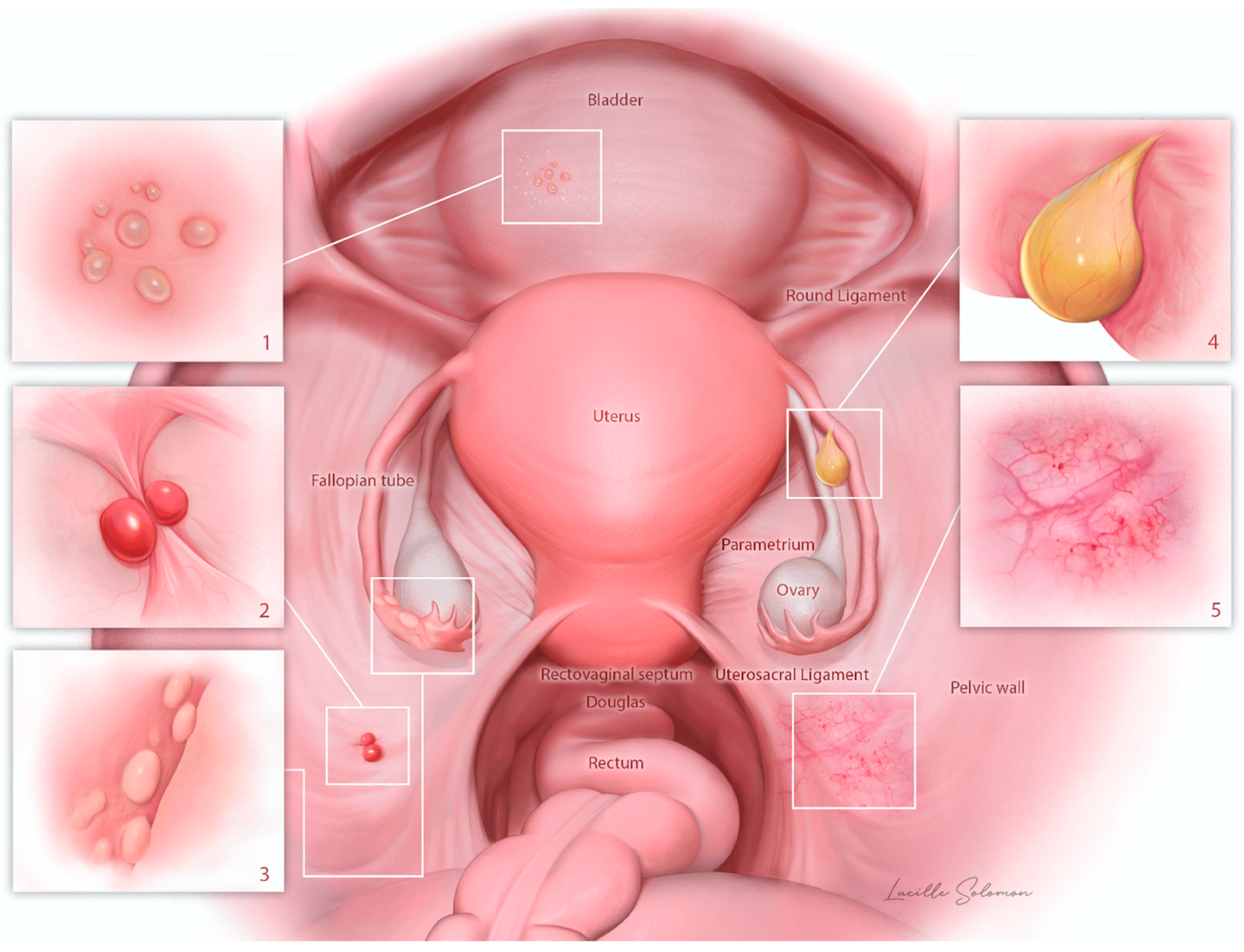

3.1.3. Anatomical Distribution

3.2. Systematic Review

3.2.1. Demographic Data—Age, Parity, Menopause, Reasons for Surgery

3.2.2. Phenotype

3.2.3. Anatomical Distribution

3.3. Comparison between Own and Systematic Review Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prentice, L.; Stewart, A.; Mohiuddin, S.; Johnson, N.P. What is endosalpingiosis? Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesseling, M.H.; De Wilde, R.L. Endosalpingiosis in laparoscopy. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 2000, 7, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, J.A. Postsalpingectomy endometriosis (endosalpingiosis). Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 1930, 20, 443–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, R.E.; Yeh, J. Müllerianosis: Four developmental (embryonic) mullerian diseases. Reprod Sci. 2013, 20, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, M.; van Altena, A.M.; Bulten, J.; Siebers, A.G.; Bekkers, R.L.M. Increased association of ovarian cancer in women with histological proven endosalpingiosis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020, 65, 101700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burney, R.O.; Giudice, L.C. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esselen, K.M.; Terry, K.L.; Samuel, A.; Elias, K.M.; Davis, M.; Welch, W.R.; Muto, M.G.; Ng, S.W.; Berkowitz, R.S. Endosalpingiosis: More than just an incidental finding at the time of gynecologic surgery? Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, M.H.; Shih, I.M. Oncogenic BRAF and KRAS mutations in endosalpingiosis. J. Pathol. 2020, 250, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwine, D.B. Age-related evolution in color appearance of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1987, 48, 1062–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, L.; Kalaitzopoulos, D.R.; Mrozek, A.; Eberhard, M.; Samartzis, N. How and where to expect endosalpingiosis intraoperatively. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 117, 461–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Conell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwel, P. The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In Joanna Briggs Institute Rewiewer’s Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Doré, N.; Landry, M.; Cadotte, M.; Schürch, W. Cutaneous Endosalpingiosis. Arch. Dermatol. 1980, 116, 909–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, R.L.; Barbatis, C.; Charnock, M. Endosalpingiosis in pregnancy. Case report. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1982, 89, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallenbach-Hellweg, G. Atypical endosalpingiosis: A case report with consideration of the differential diagnosis of glandular subperitoneal inclusions. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1987, 182, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazot, M.; Vacher Lavenu, M.C.; Bigot, J.M. Imaging of endosalpingiosis. Clin. Radiol. 1999, 54, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Tsuzuki, M.; Okubo, Y.; Aizawa, T.; Miki, M. A case of submucosal endosalpingiosis in the urinary bladder. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1999, 90, 802–805. [Google Scholar]

- Santeusanio, G.; Ventura, L.; Partenzi, A.; Spagnoli, L.G.; Kraus, F.T. Omental endosalpingiosis with endometrial-type stroma in a woman with extensive hemorrhagic pelvic endometriosis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1999, 111, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rondez, R.; Kunz, J. Serous cystadenofibroma of the epiploic appendix. A tumor of the secondary müllerian system: Case report and review of the literature. Pathologe 2000, 21, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatley, M.K.; Russell, P. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterus. J. Clin. Pathol. 2001, 54, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, P.; Idoate, M.; Corella, C. Cutaneous umbilical endosalpingiosis with severe abdominal pain. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2001, 15, 179–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCluggage, W.G.; O’Rourke, D.; McElhenney, C.; Crooks, M. Mullerian papilloma-like proliferation arising in cystic pelvic endosalpingiosis. Hum. Pathol. 2002, 33, 944–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, J.D.; Vogeley, K.J.; Howell, J.D.; Koontz, W.W.; Koo, H.P.; Amaker, B. Endosalpingiosis of bladder. J. Urol. 2002, 167, 1401–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinig, J.; Gottschalk, I.; Cirkel, U.; Diallo, R. Endosalpingiosis-an underestimated cause of chronic pelvic pain or an accidental finding? A retrospective study of 16 cases. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2002, 103, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, T.; Bontikous, S.; Smolka, G.; Vestring, T.; Schmidt, D.; Gickler, W. Cystic lymphangioma with endosalpingiosis as a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Z. Gastroenterol. 2002, 40, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Tsai, E.M.; Yang, C.H.; Kuo, C.H.; Lee, J.N. Multilobular cyst as endosalpingiosis of uterine serosa: A case report. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2003, 19, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, M. Tumor-like cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterus with florid epithelial proliferation. A case report. APMIS 2004, 112, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, G.K.; Watson, K.M.; Salisbury, J.; Du Vivier, A.W. Two cases of cutaneous umbilical endosalpingiosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 151, 924–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Sabet, L.; Izawa, J.I. Management of endosalpingiosis of urinary bladder. Urology 2004, 64, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajo, K.; Zúbor, P.; Macháleková, K.; Plank, L.; Visnovskỳ, J. Tumor-like manifestation of endosalpingiosis in uterus: A case report. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2005, 201, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.N.; Cho, M.S.; Kim, S.C.; Han, W.S. Tumor-like multilocular cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterine serosa: Possible clinical and radiologic misinterpreted. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2005, 84, 98–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunnick, G.H.; Pietzrak, P.; Richardson, N.G.; Ratcliffe, N.; Donaldson, D.R. Multiple, large, benign peritoneal cysts—A case report. Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 2005, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoubrey, A.; Houghton, O.; McCallion, K.; McCluggage, W.G. Serous adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid mesentery arising in cystic endosalpingiosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 58, 1221–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, A.H.; Ganesan, R.; Rollason, T.P. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterus. Histopathology 2006, 49, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, J.; Mensikova, J.; Mukensnabl, P.; Zamecnik, M. Mullerianosis of the urinary bladder: Report of a case with suggested metaplastic origin. Virchows Arch. 2006, 449, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanahashi, J.; Kashima, K.; Daa, T.; Kondo, Y.; Kitano, S.; Yokoyama, S. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis of the spleen. APMIS 2006, 114, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.M.; Yang, S.F.; Lin, H.C.; Juan, H.C.; Wu, W.J.; Huang, C.H.; Wang, C.J.; Li, C.C. Müllerianosis of ureter: A rare cause of hydronephrosis. Urology. 2007, 69, 1208.e9–1208.e911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.J.; Malpica, A.; Broaddus, R.R. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis presenting as an obstructive colon mass mimicking malignancy: Case report and literature review. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2007, 38, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, M.; Mistuda, A.; Shibuya, K.; Honda, Y.; Shimada, N.; Koike, J.; Sugimoto, M. Retroperitoneal lymphangioleiomyomatosis associated with endosalpingiosis. APMIS 2007, 115, 1460–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cil, A.P.; Atasoy, P.; Kara, S.A. Myometrial involvement of tumor-like cystic endosalpingiosis: A rare entity. Ultrasound Obs. Gynecol. 2008, 32, 32–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driss, M.; Zhioua, F.; Doghri, R.; Mrad, K.; Dhouib, R.; Romdhane, K.B. Cotyledonoid dissecting leiomyoma of the uterus associated with endosalpingiosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009, 280, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Vilela, D.; Izquierdo-Garcia, F.M.; Mendez-Alvarez, J.R.; Dominguez-Iglesias, F. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis inside a uterine subserous leiomyoma. Pathology 2009, 41, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavramidis, T.S.; Sapalidis, K.; Michalopoulos, N.; Karayannopoulou, G.; Cheva, A.; Papavramidis, S.T. Umbilical endosalpingiosis: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2010, 4, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneja, S.; Sidhu, R.; Khurana, A.; Sekhon, R.; Mehta, A.; Jena, A. MRI appearance of florid cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterus: A case report. Korean J. Radiol. 2010, 11, 476–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, R.E.; Mhawech-Fauceglia, P.; Odunsi, K.; Yeh, J. Pathogenesis of mediastinal paravertebral müllerian cysts of Hattori: Developmental endosalpingiosis-müllerianosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2010, 29, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniar, K.P.; Kalir, T.L.; Palese, M.A.; Unger, P.D. Endosalpingiosis of the urinary bladder: A case of probable implantative origin with characterization of benign Fallopian tube immunohistochemistry. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 18, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivia Vella, J.E.; Nair, N.; Ferryman, S.R.; Athavale, R.; Latthe, P.; Hirschowitz, L. Müllerianosis of the urinary bladder. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 19, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patonay, B.; Semer, D.; Hong, H. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis with extensive peritoneal involvement and concurrent bilateral ovarian serous cystadenoma. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 31, 773–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, P.; Nappi, L.; Santoro, A.; Bufo, P.; Greco, P. Pelvic mass-like florid cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterus: A case report and a review of literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 283, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapardiel, I.; Tobias-Gonzalez, P.; de Santiago, J. Endosalpingiosis mimicking recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Taiwan J. Obs. Gynecol. 2012, 51, 660–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kudva, R.; Hegde, P. Mullerianosis of the urinary bladder. Indian J. Urol. 2012, 28, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, R.; Gómez, A.; Galiana, N.; Campos, A.; Puente, R.; Bas, E.; Díaz-Caneja, C. Peritoneal mullerian tumor-like (endosalpingiosis-leiomyomatosis peritoneal): A hardly known entity. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 2012, 329416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheel, A.H.; Frasunek, J.; Meyer, W.; Ströbel, P. Cystic endosalpingiosis presenting as chronic back pain, a case report. Diagn. Pathol. 2013, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oida, T.; Otoshi, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Madono, K.; Momohara, C.; Imamura, R.; Takada, S.; Matsumiya, K.; Oka, K.; Tsujimoto, M. Endocervicosis/endosalpingiosis of the bladder: A case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urol. Jpn. 2013, 59, 175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Mishima, T.; Harada, J.; Kawa, G.; Okada, T. [A case of endosalpingiosis in submucosa of the urinary bladder]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2013, 59, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, K.; Kojima, F.; Ishida, M.; Iwai, M.; Kagotani, A.; Kawauchi, A. Müllerianosis and endosalpingiosis of the urinary bladder: Report of two cases with review of the literature. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 4408–4414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yığıt, S.; Dere, Y.; Yetımalar, H.; Etıt, D. Tumor-like cystic endosalpingiosis in the myometrium: A case report and a review of the literature. Turk. J. Pathol. 2014, 30, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Singhania, N.; Janakiraman, N.; Coslett, D.; Ahmad, N. Endosalpingiosis in conjunction with ovarian serous cystadenoma mimicking metastatic ovarian malignancy. Am. J. Case Rep. 2014, 15, 361–363. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.; Khan, A. Florid Cystic Endosalpingiosis. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 22, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.W.; Cheung, V.Y. Coexisting endosalpingiosis and subserous adenomyosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 315–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, L.; Steinhoff, M.; Lourenco, A.P. Endosalpingiosis presenting as multiple pelvic masses. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 34, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, A.L.; Ashok, K.P.; Anoosha, K.; Indira, C.S. Cystic endosalpingiosis of uterine parametrium- a scarcely encountered and sparsely documented entity. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, FD06–FD07. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, M.W.; Ngu, S.F.; Cheung, V.Y. Mullerian cyst of the uterus misdiagnosed as ovarian cyst on pelvic sonography. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2014, 42, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Murali, S.; Zangmo, R. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis, masquerading as malignancy in a young patient: A brief review. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014, bcr2013201645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneda, S.; Fujii, S.; Nosaka, K.; Inoue, C.; Tanabe, Y.; Matsuki, T.; Ogawa, T. MR imaging findings of mass-forming endosalpingiosis in both ovaries: A case report. Abdom Imaging 2015, 40, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Roselló, J.; Pamplona-Bueno, L.; Montero-Balaguer, B.; Desantes-Real, D.; Perales-Marín, A. Florid Cystic Endosalpingiosis (Müllerianosis) in Pregnancy. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 2016, 8621570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satgunaseelan, L.; Russell, P.; Phan-Thien, K.C.; Tran, K.; Sinclair, E. Perineural space infiltration by endosalpingiosis. Pathology 2016, 48, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanimir, M.; ChiuŢu, L.C.; Wese, S.; Milulescu, A.; Nemeş, R.N.; Bratu, O.G. Müllerianosis of the urinary bladder: A rare case report and review of the literature. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2016, 57 (Suppl. 2), 849–852. [Google Scholar]

- Zangmo, R.; Singh, N.; Kumar, S.; Vatsa, R. Second Look of Endosalpingiosis: A Rare Entity. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 2017, 67, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulayim, B.; Serin, N.; Karatas, S.; Celik, B. Cystic Endosalpingiosis of Uterus and Ovary Found on Laparoscopy: Disease of Haze. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017, 24, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.D.; McCullough, A.E. Gastrointestinal: Cystic endosalpingiosis of the spleen: CT, MR, and US imaging. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.; Park, H.S.; Cho, U.; Yoo, C.; Jung, J.-H.; Yoo, J.; Choi, H.J. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis associated with a retroperitoneal leiomyoma mimicking malignancy: A case report. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 10112–10116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quirante, F.P.; Montorfano, L.M.; Serrot, F.; E Billington, M.; Da Silva, G.; Menzo, E.L.; Szomstein, S.; Rosenthal, R.J. The case of the missing appendix: A case report of appendiceal intussusception at the site of colonic mullerianosis. Gastroenterol. Rep. (Oxf). 2017, 5, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, S.; Mendinhos, G.; Madureira, R.; Martins, A.; Veríssimo, C. Vaginal Endosalpingiosis Case Report: A Rare Entity Presenting as Intermenstrual Bleeding. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 2017, 2424392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, Y.; Sentani, K.; Matsuoka, N.; Nakayama, H.; Hattori, T.; Kudo, Y.; Yasui, W. Intramural florid cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterus after menopause. Pol. J. Pathol. 2018, 69, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, K.E.; Kenneth Schoolmeester, J.; Bakkum-Gamez, J.N. Florid cystic endosalpingiosis with uterine preservation and successful assisted reproductive therapy. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 25, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N.; Guo, X.; Bauer, J.; Hennig, M.; Kümpers, C.; Merseburger, A.S. Intravesical salpingiosis: Case report and review of the literature. Aktuelle Urol. 2018, 49, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.J.; Li, Y.C.; Jung, S.M.; Liao, Y.H.; Huang, Y.T. Masslike Cystic Endosalpingiosis in the Uterine Myometrium. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 392–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, J.; Kung, F.T. Uterine endosalpingiosis: Case report and review of the literature. Taiwan J. Obs. Gynecol. 2019, 58, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Saha, K.; Mukhopadhyay, J. Intramyometrial cystic endosalpingiosis-a rare entity in gynecological pathology: A case report and brief review of the literature. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2019, 62, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Goto, M.; Kojima, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Ishiyama, S.; Kawai, M.; Okazawa, Y.; Tomita, N.; Seki, E.; et al. A case of endosalpingiosis in the lymph nodes of the mesocolon. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 6, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortu, İ.; Arı, S.A.; Özçeltik, G.; Şahin, C.; Ergenoğlu, A.M.; Akercan, F. Laparoscopic view of endosalpingiosis in a woman with dermoid cyst and endometriosis. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2020, 22, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, F.S.; Tavallaei, M.; Ketabforoush, A.H.M.E.; Bahadorinia, M. Paratubal endosalpingiosis: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 77, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Bhat, V.; Gadabanahalli, K.; Raju, N.; Kulkarni, P. Endosalpingiosis of urinary bladder: Report on a rare entity. BJR Case Rep. 2020, 6, 20190129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, H.; Dupeux, M.; Paris, M.; Sauvan, M. Florid Cystic Endosalpingiosis and Adenomyosis of the Uterus Mimicking Malignancy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talia, K.L.; Fiorentino, L.; Scurry, J.; McCluggage, W.G. A Clinicopathologic Study and Descriptive Analysis of “Atypical Endosalpingiosis”. Int. J. Gynecol Pathol. 2020, 39, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixinho, C.; Machado-Neves, R.; Silva, P.T.; Bernardes, J.; Silva, A.C.; Amaro, T. Hysteroscopic Findings Related with the Assessment and Treatment of Uterine Florid Cystic Endosalpingiosis: A Case Report and Review of All the Published Cases. Acta Med. Port. 2021, 34, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbaiah, M.; Toi, P.C.; Dorairajan, G.; Stephen, S.N. Cystic Uterine Endosalpingiosis in a Patient with Carcinoma Endometrium. J. Midlife Health 2020, 11, 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, A.D.; Mahajan, S.A.; Kulkarni, D. Coexistence of malacoplakia and mullerianosis in the urinary bladder: An uncommon pathology. Indian J. Urol. 2020, 36, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhralddin, S.S.; Mahmood, S.N.; Qader, D.K.; Ali, A.A.; Kakamad, F.H.; Salih, A.M.; Abdullah, H.O. Mullerianosis of the urinary bladder; A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 83, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchialini, T.; Ziglioli, F.; Palmieri, G.; Barbieri, A.; Infranco, A.; Milandri, R.; Simonetti, E.; Ferretti, S.; Maestroni, U. Müllerianosis of the urinary bladder may simulate a bladder cancer: A case report. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92 (Suppl. 1), e2021148. [Google Scholar]

- Keihanian, T.; Kumar, S.R.; Ronquillo, N.; Amin, S. A rare case of endosalpingiosis masquerading as a pedunculated subepithelial colonic nodule: Utility of EUS and endoscopic resection. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 93, 1432–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ovidio, V.; Maggi, D.; Bruno, G.; Fratoni, S.; Guazzaroni, M. An Extragenital Colonic Salpingiosis. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2021, 30, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, F.C.; Lee, H.L.; Singh, R. Ovarian endosalpingiosis mimicking hydrosalpinges. Unexpected intraoperative findings and a diagnostic rollercoaster. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 2021, rjab264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busuttil, G.; German, K.; DeGaetano, J.; Scerri, A.P. The menstruating bladder, an unusual cause of haematuria. Malta Med. J. 2012, 24, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Merino, J.-M.; Guillan-Maquieira, C.; Alvarez Garcia, A.; Mendez-Diaz, C.; Sanchez Rodriguez-Losada, J.; Chantada Abal, V. Mullerianosis vesical. Prog. Obstet. Y Ginecol. 2014, 57, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carmen, S.; Rodriguez, M.; Gomez, M.A.; Cruz, M.A.; Nunez, M.A.; Sacho, M. Müllerianosis with Intestinal Metaplasia: A Case Report. Turk. J. Pathol. 2015, 31, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manucha, V.; Azar, A.; Shwayder, J.M.; Hudgens, J.L.; Lewin, J. Cystic adenomatoid tumor of the uterus. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 967–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Darakh, P.; Patil, M.; Mahajan, A. Mullerianosis of Urinary Bladder: A Great Impersonator of Malignant Urinary Bladder Tumours. Int. J. Contemp. Med. Res. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balthazar, P.; Kearns, C.; Zapparoli, M. Endosalpingiosis. Radiographics 2021, 41, E61–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almatrafi, M.H.; Alhazmi, A.M.; Almosaieed, B.N. Mullerianosis of the urinary bladder. Urol. Case Rep. 2020, 33, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, A.; Aguilera, E.; Dabancens, A. [Oviductal physiological alterations and endosalpingiosis (author’s transl)]. Reproduccion 1981, 5, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zinsser, K.R.; Wheeler, J.E. Endosalpingiosis in the omentum: A study of autopsy and surgical material. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1982, 6, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.C.; Bansal, M.; Purrazzella, R.; Malviya, V.; Strauss, L. Benign glandular inclusions in lymph nodes, endosalpingiosis, and salpingitis isthmica nodosa in a young girl with clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1983, 7, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, H.H.; Bannatyne, P.; Russell, P. Adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tubes: A clinicopathological study of eight cases. Pathology 1983, 15, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaughey, W.T.; Kirk, M.E.; Lester, W.; Dardick, I. Peritoneal epithelial lesions associated with proliferative serous tumours of ovary. Histopathology 1984, 8, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, G.J.; Samuelson, J.J.; Dehner, L.P. Cytologic diagnosis of florid peritoneal endosalpingiosis. A case report. Acta Cytol. 1986, 30, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Michael, H.; Roth, L.M. Invasive and noninvasive implants in ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential. Cancer 1986, 57, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidawy, M.K.; Silverberg, S.G. Endosalpingiosis in female peritoneal washings: A diagnostic pitfall. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1987, 6, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienemann, D.; Pickartz, H. So-called peritoneal implants of ovarian carcinomas. Problems in differential diagnosis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 1987, 182, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajigas, A.; Axiotis, C.A. Endosalpingiosis of the vermiform appendix. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1990, 9, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tohya, T.; Nakamura, M.; Fukumatsu, Y.; Katabuchi, H.; Matsuura, K.; Itoh, M.; Okamura, H. Endosalpingosis in the pelvic peritoneum and pelvic lymph nodes. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 1991, 43, 756–762. [Google Scholar]

- Biscotti, C.V.; Hart, W.R. Peritoneal serous micropapillomatosis of low malignant potential (serous borderline tumors of the peritoneum). A clinicopathologic study of 17 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1992, 16, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padberg, B.C.; Stegner, H.E.; von Sengbusch, S.; Arps, H.; Schröder, S. DNA-cytophotometry and immunocytochemistry in ovarian tumours of borderline malignancy and related peritoneal lesions. Virchows Arch A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1992, 421, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadar, N.; Krumerman, M. Possible metaplastic origin of lymph node “metastases” in serous ovarian tumor of low malignant potential (borderline serous tumor). Gynecol. Oncol. 1995, 59, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, L.C.; Bilek, K. Frequency and histogenesis of pelvic retroperitoneal lymph node inclusions of the female genital tract. An immunohistochemical study of 34 cases. Pathol. Res Pract. 1995, 191, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, V.K.; Martin, D.C. Anecdotal association of endosalpingiosis with chlamydia trachomatis IgG titers and Fitz-Hugh-Curtis adhesions. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 1995, 2, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grouls, V. [Proliferating serous papillary cystadenoma of the borderline type in myometrium of the fundus uteri]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1996, 56, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.G.; Tornos, C.; Zhuang, Z.; Merino, M.J.; Gershenson, D.M. Tumor recurrence in stage I ovarian serous neoplasms of low malignant potential. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1998, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, M.C.; Ralls, P.W.; Fu, Y.S. Transvaginal sonographic evaluation of multiple peripherally distributed echogenic foci of the ovary: Prevalence and histologic correlation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1998, 171, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Lecksell, K.; Epstein, J.I. Can immunohistochemistry enhance the detection of micrometastases in pelvic lymph nodes from patients with high-grade urothelial carcinoma of the bladder? Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1999, 112, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, A.; Kikuchi, Y.; Matsuoka, T.; Yashima, R.; Abe, R.; Suzuki, T. Endosalpingiosis of nonmetastatic lymph nodes along the stomach in a patient with early gastric cancer: Report of a case. Surg. Today 1999, 29, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluggage, W.G.; Weir, P.E. Paraovarian cystic endosalpingiosis in association with tamoxifen therapy. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 53, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A.; Sánchez-Piedra, D.; Bernaldo de Quiros, L.; Martínez, V. Endosalpingiosis (müllerianosis) of the bladder: A potential source of error in urinary cytology. Cytopathology 2000, 11, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risberg, B.; Davidson, B.; Dong, H.P.; Nesland, J.M.; Berner, A. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping of serous effusions and peritoneal washings: Comparison with immunocytochemistry and morphological findings. J. Clin. Pathol. 2000, 53, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Matsui, K.; Travis, W.D.; Gonzalez, R.; Terzian, J.A.; Rosai, J.; Moss, J.; Ferrans, V.J. Association of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) with endosalpingiosis in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes: Report of two cases. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001, 9, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluggage, W.G.; Clements, W.D. Endosalpingiosis of the colon and appendix. Histopathology 2001, 39, 645–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malpica, A.; Deavers, M.T.; Gershenson, D.; Tortolero-Luna, G.; Silva, E.G. Serous tumors involving extra-abdominal/extra-pelvic sites after the diagnosis of an ovarian serous neoplasm of low malignant potential. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001, 25, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalir, T.; Wang, B.Y.; Goldfischer, M.; Haber, R.S.; Reder, I.; Demopoulos, R.; Cohen, C.J.; Burstein, D.E. Immunohistochemical staining of GLUT1 in benign, borderline, and malignant ovarian epithelia. Cancer 2002, 94, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camatte, S.; Morice, P.; Atallah, D.; Pautier, P.; Lhommé, C.; Haie-Meder, C.; Duvillard, P.; Castaigne, D. Lymph node disorders and prognostic value of nodal involvement in patients treated for a borderline ovarian tumor: An analysis of a series of 42 lymphadenectomies. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2002, 195, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilos, G.A.; Vilos, A.W.; Haebe, J.J. Laparoscopic findings, management, histopathology, and outcome of 25 women with cyclic leg pain. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 2002, 9, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, J.L.; Lynn, A.A. Histologic features of surgically removed fallopian tubes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002, 126, 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fausett, M.B.; Zahn, C.M.; Kendall, B.S.; Barth, W.H. The significance of psammoma bodies that are found incidentally during endometrial biopsy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shappell, H.W.; Riopel, M.A.; Smith Sehdev, A.E.; Ronnett, B.M.; Kurman, R.J. Diagnostic criteria and behavior of ovarian seromucinous (endocervical-type mucinous and mixed cell-type) tumors: Atypical proliferative (borderline) tumors, intraepithelial, microinvasive, and invasive carcinomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002, 26, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, J.; Seemüller, F.; Löhrs, U. K-RAS mutations in ovarian and extraovarian lesions of serous tumors of borderline malignancy. Lab Invest. 2003, 83, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yoo, J.; Choi, H.J.; Kang, S.J. M llerian-Type Gland Inclusions in Pelvic Lymph Nodes Mimicking Metastasis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cancer Res. Treat. 2003, 35, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrick, K.S.; Milvenan, J.S.; Albores-Saavedra, J. Serous tumor of low malignant potential arising in inguinal endosalpingiosis: Report of a case. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2003, 22, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Ylagan, L.R. Pelvic washing cytology in serous borderline tumors of the ovary using ThinPrep: Are there cytologic clues to detecting tumor cells? Diagn Cytopathol. 2004, 30, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.L.; Frates, M.C.; Muto, M.G.; Welch, W.R. Small echogenic foci in the ovaries: Correlation with histologic findings. J. Ultrasound Med. 2004, 23, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.K.; Moritani, S.; Urabe, M.; Bamba, M.; Ueda, M.; Nishino, T.; Muramatsu, M.; Kaneko, C. Cytologic diagnosis of endosalpingiosis with pregnant women presenting in peritoneal fluid: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004, 30, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Leong, A.S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, I.; Ahn, G.H.; Kim, H.S.; Chun, Y.K. Calretinin, CD34, and alpha-smooth muscle actin in the identification of peritoneal invasive implants of serous borderline tumors of the ovary. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascu, P.C.; Vilos, G.A.; Ettler, H.C.; Abu-Rafea, B.; Hollet-Caines, J.; Ahmad, R. Histopathologic findings on uterosacral ligaments in women with chronic pelvic pain and visually normal pelvis at laparoscopy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2006, 13, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, J.K.; Balzer, B.L.; Longacre, T.A. Lymph node involvement in ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential (borderline tumors): Pathology, prognosis, and proposed classification. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, I.; Encinas, A.; Gradil, C.; Davide, J.; Daniel, J.; Graça, L.M.; Teixeira, M. Endosalpingiosis of choledochal duct. Surgery 2007, 142, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pollheimer, M.J.; Leibl, S.; Pollheimer, V.S.; Ratschek, M.; Langner, C. Cystic endosalpingiosis of the appendix. Virchows Arch. 2007, 450, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallón-Aguilar, L.; Olano-Acosta, C.; López-Porras, M.; Flores-Cortés, M.; Pareja-Ciuró, F. Endosalpingiosis of the appendix. Cir. Esp. 2009, 85, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, J.P.; Li, A.; Li, H.L. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis with florid endosalpingiosis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 192, 826–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.; Young, R.H.; Misdraji, J. Ruptured appendiceal diverticula mimicking low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009, 33, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Wong, C.; Russell, P. Pelvic lymphangioleiomyomatosis associated with endosalpingiosis. Pathology 2009, 41, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herce, J.M.; Luque, V.R.; Luque, J.A.; García, P.M.; Gómez, D.D. Association of retroperitoneal lymphangioleiomyomatosis with endosalpingiosis: A case report. Cases J. 2009, 2, 6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corben, A.D.; Nehhozina, T.; Garg, K.; Vallejo, C.E.; Brogi, E. Endosalpingiosis in axillary lymph nodes: A possible pitfall in the staging of patients with breast carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djordjevic, B.; Clement-Kruzel, S.; Atkinson, N.E.; Malpica, A. Nodal endosalpingiosis in ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential with lymph node involvement: A case for a precursor lesion. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 1442–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karafin, M.; Parwani, A.; Netto, G.J.; Illei, P.B.; Epstein, J.I.; Ladanyi, M.; Argani, P. Diffuse expression of PAX2 and PAX8 in the cystic epithelium of mixed epithelial stromal tumor, angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts, and primary renal synovial sarcoma: Evidence supporting renal tubular differentiation. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, H.; Cho, H.Y.; Jung, S.J.; Kim, K.-R.; Ro, J.Y.; Shen, S.S. Carcinoma of müllerian origin presenting as colorectal cancer: A clinicopathologic study of 13 Cases. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2011, 15, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Abushahin, N.; Pang, S.; Xiang, L.; Chambers, S.K.; Fadare, O.; Kong, B.; Zheng, W. Tubal origin of ‘ovarian’ low-grade serous carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 1488–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurman, R.J.; Vang, R.; Junge, J.; Hannibal, C.G.; Kjaer, S.K.; Shih, I.M. Papillary tubal hyperplasia: The putative precursor of ovarian atypical proliferative (borderline) serous tumors, noninvasive implants, and endosalpingiosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarode, V.R.; Euhus, D.; Thompson, M.; Peng, Y. Atypical endosalpingiosis in axillary sentinel lymph node: A potential source of false-positive diagnosis of metastasis. Breast J. 2011, 17, 672–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpica, A.; Sant’Ambrogio, S.; Deavers, M.T.; Silva, E.G. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the female peritoneum: A clinicopathologic study of 26 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneige, N.; Dawlett, M.; Kologinczak, T.; Guo, M. Endosalpingiosis in Peritoneal Washings in Women with Benign Gynecologic Conditions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013, 121, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, G.; Stewart, J.; Deavers, M.; Lu, K.; Sneige, N. Peritoneal washing cytology in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomies: A 10-year experience and reappraisal of its clinical utility. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, B.; Malpica, A. Ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential with nodal low-grade serous carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Vilela, D.; Izquierdo, F.M.; Riera-Velasco, J.R.; Escobar-Stein, J. Endosalpingiosis can mimic malignant glands and result in a false positive mesorectal resection margin. Virchows Arch. 2012, 461, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, J.J.; Vilos, G.A.; Ettler, H.C.; Marks, J.; Vilos, A.G.; Abu-Rafea, B. Granulosa cells in the uterosacral ligament: Case report and review of the literature. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2012, 19, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, M.; Brasanac, D.; Stojicic, M. Cutaneous inguinal scar endosalpingiosis and endometriosis: Case report with review of literature. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2013, 35, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Sánchez, C.; Ocón Revuelta, E.M.; Fontillón, M.; Argüelles Salido, E.; Medina López, R.A. [Endosalpingiosis of the bladder. A case report]. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2013, 66, 605–608. [Google Scholar]

- Mincik, I.; Mytnik, M.; Straka, L.; Breza, J.; Vilcha, I. Inflammatory pseudotumour of urinary bladder—A rare cause of massive macroscopic haematuria. Bratisl. Lek. Listy. 2013, 114, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.H.; Omeroglu, G.; Kanber, Y.; Omeroglu, A. Endosalpingiosis in axillary lymph nodes simulating metastatic breast carcinoma: A potential diagnostic pitfall. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 21, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilsher, M.; Snook, K.L. Endosalpingiosis in an axillary lymph node with synchronous micro-metastatic mammary carcinoma. Pathology 2014, 46, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, E.; Cimino-Mathews, A.; Argani, C.; Kronz, J.; Vang, R.; Argani, P. A subset of nondescript axillary lymph node inclusions have the immunophenotype of endosalpingiosis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 1612–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Park, J.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, H.H.; Chung, S.H.; Jeon, D.S. Endosalpingiosis in postmenopausal elderly women. J. Menopausal. Med. 2014, 20, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerdem, U.; Hoda, S.A. Endosalpingiosis of axillary sentinel lymph node: A mimic of metastatic breast carcinoma. Breast J. 2015, 21, 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomani, L.; Calhoun, B.C.; Biscotti, C.V.; Grobmyer, S.R.; Sturgis, C.D. Endosalpingiosis of Axillary Lymph Nodes: A Rare Histopathologic Pitfall with Clinical Relevance for Breast Cancer Staging. Case Rep. Pathol. 2016, 2016, 2856358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chakhtoura, G.; Nassereddine, H.; Gharios, J.; Khaddage, A. Isolated endosalpingiosis of the appendix in an adolescent girl. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. 2016, 44, 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, P.; van der Griend, R.; Anderson, L.; Yu, B.; O’Toole, S.; Simcock, B. Evidence for lymphatic pathogenesis of endosalpingiosis. Pathology 2016, 48, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, P.; Anderson, L. Evidence for lymphatic pathogenesis of endosalpingiosis: The more things change, the more they stay the same. Pathology 2016, 48, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, J.V.; Prabhu, S.; Wiley, E. Coexistent Isolated Tumor Cell Clusters of Infiltrating Lobular Carcinoma and Benign Glandular Inclusions of Müllerian (Endosalpingiosis) Type in an Axillary Sentinel Node: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2016, 24, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallan, A.J.; Antic, T. Benign müllerian glandular inclusions in men undergoing pelvic lymph node dissection. Hum. Pathol. 2016, 57, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barresi, V.; Barns, D.; Grundmeyer Rd, R.; Rodriguez, F.J. Cystic endosalpingiosis of lumbar nerve root: A unique presentation. Clin. Neuropathol. 2017, 36, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpathiou, G.; Da Cruz, V.; Patoir, A.; Forest, F.; Hag, B.; Tiffet, O.; Peoc’h, M. Mediastinal cyst of müllerian origin: Evidence for developmental endosalpingiosis. Pathology 2017, 49, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Sánchez, L.E.; Hernández Barroso, M.; Hernández Hernández, G.; Soto Sánchez, A.; Barrera Gómez, M. Endosalpingiosis as an obstructive entity simulating a sigma neoplasm. Cir. Esp. 2017, 95, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.K.; Savas, Y.; Furuncuoglu, Y.; Cevher, T.; Demiral, S.; Tabandeh, B.; Aslan, M. Imaging Findings of the Unusual Presentations, Associations and Clinical Mimics of Acute Appendicitis. Eurasian J. Med. 2017, 49, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, Y.; Tabata, J.; Yorozu, T.; Kitai, S.; Ueda, K.; Saito, M.; Yanaihara, N.; Yamada, K.; Okamoto, A. Polypoid endometriosis of the ovary and müllerianosis of pelvic lymph nodes mimicking an ovarian carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Int. Cancer Conf. J. 2017, 6, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall, C.P.; Sharp, D.S.; Zynger, D.L. Benign Müllerian Inclusions in Lymphadenectomies for Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Radiologic and Pathologic Mimic of Metastases. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2017, 15, e877–e879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, R.A.R.; Taheini, K.M.; Sheikh, S.S. Mullerianosis of the Urinary Bladder: A Case Report. Case Rep. Oncol. 2018, 11, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, K.R.; Singh, C.; Neychev, V. Endosalpingiosis of the Gallbladder: A Unique Complication of Ruptured Ectopic Pregnancy. Cureus 2019, 11, e5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiino, S.; Yoshida, M.; Jimbo, K.; Asaga, S.; Takayama, S.; Maeshima, A.; Tsuda, H.; Kinoshita, T.; Hiraoka, N. Two rare cases of endosalpingiosis in the axillary sentinel lymph nodes: Evaluation of immunohistochemical staining and one-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) assay in patients with breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 2019, 474, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, M.; Chen, A.; Gonzalez, R.S. Clinicopathologic findings in gynecologic proliferations of the appendix. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 92, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, H.Y.; Alhatem, A.; Barlog, L.; Heller, D. A Rare Mimic of Malignancy: Papillary Endosalpingiosis. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 28, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.; Fulmali, R.; McCluggage, W.G. Low-grade Serous Carcinoma Arising in Inguinal Nodal Endosalpingiosis: Report of 2 Cases and Literature Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2020, 39, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, G.; Jorns, J.M. Endosalpingiosis and other benign epithelial inclusions in breast sentinel lymph nodes. Breast J. 2020, 26, 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.G.; Kim, G.; Bakkar, R.; Bozdag, Z.; Shaye-Brown, A.; Loghavi, S.; Stolnicu, S.; Hadareanu, V.; Bulgaru, D.; Cayax, L.I.; et al. Histology of the normal ovary in premenopausal patients. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2020, 46, 151475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancheti, S.; Somal, P.K.; Chaudhary, D.; Khandelwal, S. Mullerianosis of urinary bladder: The great impersonator. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2020, 63, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Sardana, R.; Quddus, M.R.; Harigopal, M. Epithelium Involving Bilateral Axillary Lymph Nodes: Metastasis, Misplaced, or Mullerian! Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 29, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumiya, H.; Todo, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Yamada, R.; Minowa, K.; Tsuruta, T.; Kurosu, H.; Minobe, S.; Kato, H.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Diagnostic criteria of sentinel lymph node micrometastasis or macrometastasis based on tissue rinse liquid-based cytology in gynecological cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 25, 2138–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.L.; Farrell, R.; Kamath, V.; Ho-Shon, I.; Yap, F. Concordant PET/CT and ICG positive lymph nodes in endometrial cancer: A case of mistaken identity. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, rjz377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, J.; Wasickanin, M.; Katz, T.A.; Wickersham, E.L.; Steed, D.O.E.; Simper, N. Prevalence of endosalpingiosis and other benign gynecologic lesions. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, e0232487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivo, M.Z.; Tacha, D.E.; Hansel, D.E. Expression of uroplakin II and GATA-3 in bladder cancer mimickers: Caveats in the use of a limited panel to determine cell of origin in bladder lesions. Hum. Pathol. 2021, 113, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, M.; Juncos, A.C.; Ganzer, L.M.; Cardona, F.P.; Abrego, M. Uterine Florid Cystic Endosalpingiosis with Conservative Surgery. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 29, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutschka, B.G.; Lauchlan, S.C. Endosalpingiosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1980, 55 (Suppl. 3), 57S–60S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcintosh, A.; Teo, U.L.; Millan, D.W.M.; Alexander-Sefre, F. Endosalpingiosis Masquerading as Ovarian Carcinoma and Presenting on Cervical Smear. Scott. Med. J. 2008, 53, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura Sanchez, J.; Solis Garcia, E.; Gonzalez Serrano, T. Serous papillary adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon arising in cystic endosalpingiosis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Rev. Esp. Patol. 2008, 41, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Krentel, H.; Hucke, J. Disseminated Hormone-Producing Leiomyomatosis after Laparoscopic Supracervical Hysterectomy: A Case Report. Geburtshilfe Frauenheikunde 2010, 70, 894–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolnicu, S.; Preda, O.; Kinga, S.; Marian, C.; Nicolau, R.; Andrei, S.; Nicolae, A.; Nogales, F.F. Florid, papillary endosalpingiosis of the axillary lymph nodes. Breast J. 2011, 17, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magill, L.; Rajan, P.; Zafar, N.; Seywright, M.; Hendry, D. Endocervicosis and endosalpingiosis of the urinary bladder: A case report. Br. J. Med. Surg. Urol. 2011, 4, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Rosenthal, D.L.; Erozan, Y.S. Mullerianosis of the urinary bladder: Report of a case with diagnosis suggested in urine cytology and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012, 40, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, S.; Jung, J.H.; Choi, H.J.; Kang, C.S. Intramural florid cystic endosalpingiosis of the uterus: A case report and review of the literature. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 54, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacalbasa, N.B.; Irina, T.D. Lymph node involvement in endosalpingiosis. A case report and literature review. Ginecoeu 2016, 12, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, P.F.; Fernández, J.A.; Sánchez, B.C.G.I.P.; Cañal, P.L.; Gil, S.P.; Gil, S.P.; Ferrera, y.C.F. Dispositivos intratubáricos Essure® asociados a dolor pélvico crónico y endosalpingiosis. Prog. De Obstet. Y Ginecol. 2017, 60, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, L.S.; Trusso, W.N.; Puigoriol, E.B.; Weakner, S.M.; Cros, N.E. Appendicular endosalpingiosis. Prog. Obstet. Y Ginecol. 2018, 61, 176–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ilnitsky, S.; Abu Rafea, B.; Vilos, A.G.; Vilos, G.A. Pelvic Peritoneal Pockets: Distribution, Histopathology, and Clinical Significance. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2019, 41, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudor, J.; Williams, T.R.; Myers, D.T.; Umar, B. Appendiceal endosalpingiosis: Clinical presentation and imaging appearance of a rare condition of the appendix. Abdom. Radiol. 2019, 44, 3246–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyna-Villasmil, E.; Torres-Cepeda, D.; Rondon-Tapia, M. Müllerianosis of cervix. Case report. Rev. Peru. Ginecol. Y Obstet. 2020, 66, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sajnani, J.; Swan, K. Endosalpingiosis: Clinical Presentation and Coexisting Pathology. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, 83s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Inoue, C.; Mukuda, N.; Murakami, A.; Yamaji, D.; Yunaga, H.; Nosaka, K. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of endosalpingiosis: A case report. Acta Radiol Open. 2021, 10, 20584601211022504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J.; Vang, R.; Argani, P.; Cimino-Mathews, A. Endosalpingiosis Is Negative for GATA3. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2021, 145, 1448–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.; Byrnes, K.G.; Walsh, K.; O’Sullivan, G.; McHale, T. Renal endometriosis mimicking a malignancy–a rare case of Reno-Mullerian fusion. Researchsquare 2021, 3, 2339–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Song, S.H.; Shin, B.K.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, N.W.; Lee, K.W. Primary clear cell carcinoma of a paratubal cyst: A case report with literature review. Aust. N Z J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 51, 284–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Angelico, G.; Inzani, F.; Spadola, S.; Arciuolo, D.; Valente, M.; Fiorentino, V.; Mulè, A.; Scambia, G.; Zannoni, G.F. The Many Faces of Endometriosis-Related Neoplasms in the Same Patient: A Brief Report. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2020, 85, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, S.; Kandemir, S.; Yavuz, O.; Koyuncuoglu, M.; Ulukus, E.C.; Celiloglu, M. Persistent tubal epithelium in ovaries after salpingectomy. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2020, 41, 919–923. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, N.C.S.; Maher, P.J.; Pyman, J.M.; Readman, E.; Gordon, S. Endosalpingiosis, an unrecognized condition: Report and literature review. Gynecol. Surg. 2004, 1, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenczy, A.; Talens, M.; Zoghby, M.; Hussain, S.S. Ultrastructural studies on the morphogenesis of psammoma bodies in ovarian serous neoplasia. Cancer 1977, 39, 2451–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Pitman, M.B.; Torous, V.F. Determining the significance of psammoma bodies in pelvic washings: A 10-year retrospective review. Cancer Cytopathol. 2021, 129, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, K.W.; Cheung, V.Y. Response: Cystic Endosalpingiosis or Multicystic Mesothelioma? J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2016, 23, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Zhao, L.; Weng Lao, I.; Yu, L.; Wang, J. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma: A 17-year single institution experience with a series of 75 cases. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2019, 38, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esselen, K.M.; Ng, S.K.; Hua, Y.; White, M.; Jimenez, C.A.; Welch, W.R.; Drapkin, R.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Ng, S.W. Endosalpingiosis as it relates to tubal, ovarian and serous neoplastic tissues: An immunohistochemical study of tubal and Müllerian antigens. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 132, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.G.; Lawson, B.C.; Ramalingam, P.; Liu, J.; Shehabeldin, A.; Marques-Piubelli, M.L.; Malpica, A. Precursors in the ovarian stroma: Another pathway to explain the origin of ovarian serous neoplasms. Hum. Pathol. 2022, 127, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwine, D.B. ‘Invisible’ microscopic endometriosis: A review. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2003, 55, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Own Population | Systematic Review | p-Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.2 (SD 16.4) | 45.7 (SD 14.4) | 0.003 | ||

| Menopausal status | 0.232 | ||||

| premenopausal | 75.3% (58/77) | 65.9% (58/88) | |||

| postmenopausal | 24.7% (19/77)) | 34.1% (30/88) | |||

| Parity | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 70.1% (54/77) | 22% (11/50) | |||

| I | 7.8% (6/77) | 20% (10/50) | |||

| ≥II | 22.1% (17/77) | 58% (29/50) | |||

| Endometriosis | 53.2% (41/77) | 9% (106/1174) | <0.001 | ||

| rASRM | I/II | 61% (25/41) | 56.3% (9/16 *) | ||

| III/IV | 39% (16/41) | 43.8% (7/16 *) | |||

| Neoplasm ** | 28.6% (22/77) | 9.4% (110/1174) | <0.001 | ||

| cervical | 1.3% (1/77) | 6.4% (7/110) | |||

| uterine | 10.4% (8/77) | 30.9% (34/110) | |||

| ovarian | 18.2% (14/77) | 19.1% (21/110) | |||

| breast | 2.6% (2/77) | 17.3% (19/110) | |||

| intestinal | 2.6% (2/77) | 2.7% (3/110) | |||

| other | 2.6% (2/77) | 15.5% (17/110) | |||

| Own Population (n = 77) | Systematic Review (n = 295) | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelvic pain | 29.9% (n = 23) | 21.4% (n = 63) | 0.115 |

| Gynecologic neoplasm * | 27.3% (n = 21) | 15.6% (n = 46) | 0.018 |

| Fertility diagnostic | 20.8% (n = 16) | 7.1% (n = 21) | <0.001 |

| Suspicious pelvic mass | 15.6% (n = 12) | 28.9% (n = 85) | 0.019 |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | 3.9% (n = 3) | 5.1% (n = 15) | 0.665 |

| Bowel disorder | 1.3% (n = 1) | 1.4% (n = 4) | 0.969 |

| Risk reduction surgery | 1.3% (n = 1) | 1.0% (n = 3) | 0.831 |

| Breast cancer | 0% (n = 0) | 6.1% (n = 18) | 0.026 |

| Suspicion of urinary tract neoplasm | 0% (n = 0) | 5.1% (n = 15) | 0.043 |

| Urinary tract disorder | 0% (n = 0) | 3.7% (n = 11) | 0.085 |

| Inguinal mass | 0% (n = 0) | 2.0% (n = 6) | 0.207 |

| Intestinal cancer | 0% (n = 0) | 1.0% (n = 3) | 0.374 |

| Cesarean section | 0% (n = 0) | 0.7% (n = 2) | 0.469 |

| Ectopic pregnancy | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 1) | 0.609 |

| Paravertebral cyst | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 1) | 0.609 |

| Spleenic mass | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 1) | 0.609 |

| Own Population | Systematic Review | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 50) | (n = 99) | ||||

| Size mean (mm) | 3.6 (range 1–40) | 48.5 (range 2–250) | p < 0.001 * | ||

| Shape | |||||

| symmetric | 64% (n = 32) | 36.4% (n = 36) | p = 0.001 | ||

| irregular | 36% (n = 18) | 63.6% (n = 63) | |||

| Color | |||||

| transparent | 48% (n = 24) | 31.3% (n = 31) | p = 0.005 | ||

| white | 22% (n = 11) | 10.1% (n = 10) | |||

| yellow | 10% (n = 5) | 15.2% (n = 15) | |||

| light red | 16% (n = 8) | 18.2% (n = 18) | |||

| dark red/brown | 4% (n = 2) | 25.3% (n = 25) | |||

| Height | |||||

| flat | 70% (n = 35) | 8.1% (n = 8) | p < 0.001 | ||

| polypous | 22% (n = 11) | 15.2% (n = 15) | |||

| cystic | 8% (n = 4) | 76.8% (n = 76) | |||

| Surface | |||||

| smooth | 84% (n = 42) | 88.9% (n = 88) | p = 0.398 | ||

| irregular | 16% (n = 8) | 11.1% (n = 11) | |||

| Consistency | |||||

| soft | 88% (n = 44) | 67.7% (n = 67) | p = 0.007 | ||

| solid | 12% (n = 6) | 32.3% (n = 32) | |||

| Calcification | |||||

| no | 76% (n = 38) | 87.9% (n = 78) | p = 0.063 | ||

| yes | 24% (n = 12) | 12.1% (n = 12) | |||

| Adhesions | |||||

| no | 68% (n = 34/50) | 91.9% (n = 91/99) | p = 0.002 | ||

| string | 8% (n = 4/50) | 1% (n = 1/99) | |||

| area | 14% (n = 7/50) | 3% (n = 3/99) | |||

| dense | 10% (n = 5/50) | 4% (n = 4/99) | |||

| Endometriosis | |||||

| no | 74% (n = 37/50) | 88.9% (n = 88/99) | p = 0.054 | ||

| peritoneal | 16% (n = 8/50) | 8.1% (n = 8/99) | |||

| deep | 10% (n = 5/50) | 3% (n = 3/99) | |||

| Pattern type | |||||

| 1 | vesicular | 62% (n = 31/50) | 8.1% (n = 8/99) | p < 0.001 | |

| 2 | polypous | 6% (n = 3/50) | 11.1% (n = 11/99) | ||

| 3 | fimbrial like | 12% (n = 6/50) | 1% (n = 1/99) | ||

| 4 | cystic | 10% (n = 5/50) | 49.5% (n = 49/99) | ||

| 5 | unusual | 10% (n = 5/50) | 30.3% (n = 30/99) | ||

| Own Population | Systematic Review | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 77 | n = 1174 | p-Values | ||

| Urinary tract | 19.5% (n = 15) | 4.1% (n = 48) | <0.001 | |

| Bladder | 19.5% (n = 15) | 4% (n = 47) | <0.001 | |

| Peritoneal | 19.5% (n = 15) | 1% (n = 12) | <0.001 | |

| Deep | 0% (n = 0) | 3% (n = 35) | 0.124 | |

| Ureter | 0% (n = 0) | 0.1% (n = 1) | 0.798 | |

| Vagina | 0% (n = 0) | 0.1% (n = 1) | 0.798 | |

| Uterus | 6.5% (n = 5) | 6.3% (n = 74) | 0.947 | |

| Surface | 6.5% (n = 5) | 4.7% (n = 56) | 0.496 | |

| Deep | 0% (n = 0) | 1.4% (n = 17) | 0.288 | |

| Ovary | 15.6% (n = 12) | 23.2% (n = 272) | <0.001 | |

| Left | 5.2% (n = 4) | 2.6% (n = 30) | 0.168 | |

| Right | 10.4% (n = 8) | 2.9%(n = 34) | <0.001 | |

| NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 17.7% (n = 208) | <0.001 | |

| Fallopian tube | 15.6% (n = 12) | 20.4% (n = 239) | <0.001 | |

| Left | 6.5% (n = 5) | 0.6% (n = 7) | <0.001 | |

| Right | 9.1% (n = 7) | 0.5% (n = 6) | <0.001 | |

| NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 19.3% (n = 226) | <0.001 | |

| Parametrium | 11.7% (n = 9) | 3.2% (n = 38) | <0.001 | |

| Left | 7.8% (n = 6) | 0.3% (n = 4) | <0.001 | |

| Right | 3.9% (n = 3) | 0.4% (n = 5) | <0.001 | |

| NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 2.5% (n = 29) | 0.163 | |

| Rectovaginal septum | 2.6% (n = 2) | 0.1% (n = 1) | <0.001 | |

| Sacrouterine ligament | 24.7% (n = 19) | 1.2% (n = 14) | <0.001 | |

| Left | 7.8% (n = 6) | 0.4% (n = 5) | <0.001 | |

| Right | 16.9% (n = 13) | 0.5% (n = 6) | <0.001 | |

| NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 3) | 0.657 | |

| Pelvic sidewall | 18.2% (n = 14) | 1.1% (n = 13) | <0.001 | |

| Left | 9.1% (n = 7) | 0.4% (n = 5) | <0.001 | |

| Right | 6.5% (n = 5) | 0.3% (n = 4) | <0.001 | |

| NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 4) | 0.608 | |

| Douglas | 20.7% (n = 16) | 6.7% (n = 79) | <0.001 | |

| Peritoneal NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 7.3% (n = 86) | 0.014 | |

| Retroperitoneum | 0% (n = 0) | 0.5% (n = 6) | 0.529 | |

| Lumbar nerve root | 0% (n = 0) | 0.1% (n = 1) | 0.798 | |

| Paravertebral | 0% (n = 0) | 0.2% (n = 2) | 0.717 | |

| NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 3) | 0.657 | |

| Abdominal wall | 3.9% (n = 3) | 1.2% (n = 14) | 0.047 | |

| Left | 2.6% (n = 2) | 0.1% (n = 1) | <0.001 | |

| Right | 1.3% (n = 1) | 0% (n = 0) | <0.001 | |

| Umbilicus | 0% (n = 0) | 0.4% (n = 5) | 0.566 | |

| Inguinal | 0% (n = 0) | 0.6% (n = 7) | 0.497 | |

| NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 0.1% (n = 1) | 0.798 | |

| Abdominal organs | 10.4% (n = 8) | 8% (n = 94) | 0.459 | |

| Small bowel | 0% (n = 0) | 0.2% (n = 2) | 0.717 | |

| Sigma/Colon | 2.6% (n = 2) | 1.2% (n = 15) | 0.333 | |

| Appendix | 1.3% (n = 1) | 2.4% (n = 28) | 0.539 | |

| Omentum | 6.5% (n = 5) | 5.5% (n = 65) | 0.723 | |

| Spleen | 0% (n = 0) | 0.2% (n = 2) | 0.717 | |

| Gallbladder/ductus choledochus | 0% (n = 0) | 0.2% (n = 2) | 0.717 | |

| Pleura | 0% (n = 0) | 0.1% (n = 1) | 0.798 | |

| Lymph node | 7.8% (n = 6) | 18.5% (n = 217) | <0.001 | |

| Inguinal | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 3) | 0.657 | |

| Pelvic | 5.2% (n = 4) | 3.9% (n = 46) | <0.001 | |

| Paraaortic | 2.6% (n = 2) | 0.8% (n = 10) | <0.001 | |

| Pelvi-abdominal NOS | 0% (n = 0) | 9.7% (n = 114) | 0.004 | |

| Axillary | 0% (n = 0) | 3.3% (n = 39) | 0.104 | |

| Neck | 0% (n = 0) | 0.3% (n = 4) | 0.608 | |

| Mediastinal | 0% (n = 0) | 0.1% (n = 1) | 0.798 | |

| Abdominal washing | 0% (n = 0) | 4.5% (n = 53) | 0.057 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burla, L.; Kalaitzopoulos, D.R.; Mrozek, A.; Eberhard, M.; Samartzis, N. Intraoperative Appearance of Endosalpingiosis: A Single-Center Experience of Laparoscopic Findings and Systematic Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7006. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237006

Burla L, Kalaitzopoulos DR, Mrozek A, Eberhard M, Samartzis N. Intraoperative Appearance of Endosalpingiosis: A Single-Center Experience of Laparoscopic Findings and Systematic Review of Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(23):7006. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237006

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurla, Laurin, Dimitrios Rafail Kalaitzopoulos, Anna Mrozek, Markus Eberhard, and Nicolas Samartzis. 2022. "Intraoperative Appearance of Endosalpingiosis: A Single-Center Experience of Laparoscopic Findings and Systematic Review of Literature" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 23: 7006. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237006

APA StyleBurla, L., Kalaitzopoulos, D. R., Mrozek, A., Eberhard, M., & Samartzis, N. (2022). Intraoperative Appearance of Endosalpingiosis: A Single-Center Experience of Laparoscopic Findings and Systematic Review of Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(23), 7006. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237006