Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients with Distinct Postoperative Fibrinolytic Phenotypes Require Different Antifibrinolytic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

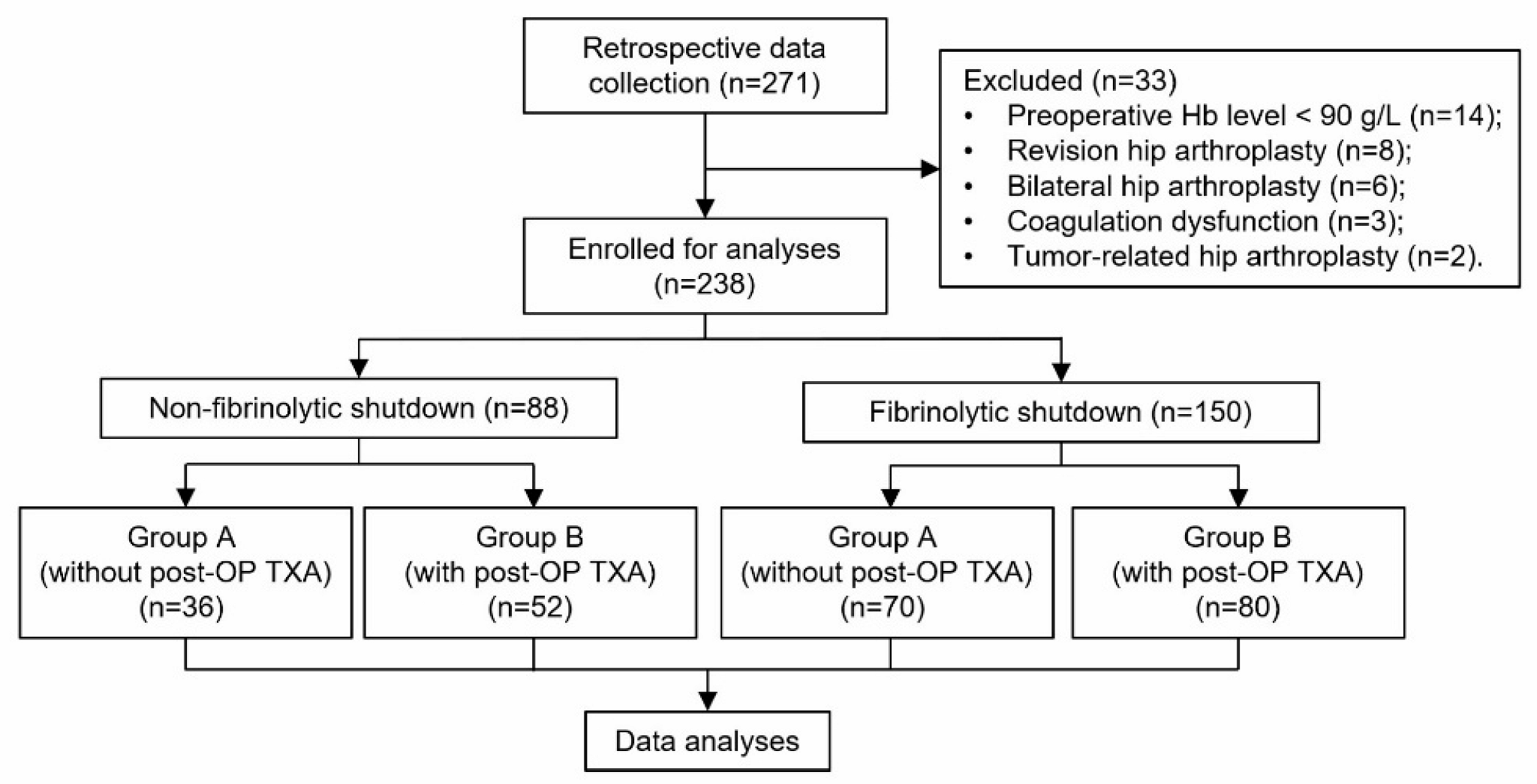

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Surgical Procedure and Perioperative Management

2.4. Outcome Measurements

2.5. Thromboelastography (TEG)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.2. Primary Outcomes

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferguson, R.J.; Palmer, A.J.; Taylor, A.; Porter, M.L.; Malchau, H.; Glyn-Jones, S. Hip replacement. Lancet 2018, 392, 1662–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Huang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Xie, J.; Chen, G.; Pei, F. Multiple-Dose Intravenous Tranexamic Acid Further Reduces Hidden Blood Loss After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 2940–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-D.; Tian, M.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tao, Y.-Z.; Shao, L.; Luo, C.; Xiao, P.-C.; Zhu, Z.-L.; Liu, J.-C.; et al. Efficacy of a three-day prolonged-course of multiple-dose versus a single-dose of tranexamic acid in total hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakur, H.; Roberts, I.; Bautista, R.; Caballero, J.; Coats, T.; Dewan, Y.; El-Sayed, H.; Gogichaishvili, T.; Gupta, S.; Herrera, J.; et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayet-Ageron, A.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Ker, K.; Shakur, H.; Ageron, F.X.; Roberts, I. Effect of treatment delay on the effectiveness and safety of antifibrinolytics in acute severe haemorrhage: A meta-analysis of individual patient-level data from 40 138 bleeding patients. Lancet 2018, 391, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Gonzalez, E.; Chapman, M.P.; Chin, T.L.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; Sauaia, A. Hyperfibrinolysis, physiologic fibrinolysis, and fibrinolysis shutdown: The spectrum of postinjury fibrinolysis and relevance to antifibrinolytic therapy. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014, 77, 811–817; discussion 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Neal, M.D.; Sheppard, F.R.; Kornblith, L.Z.; Draxler, D.F.; Walsh, M.; Medcalf, R.L.; Cohen, M.J.; Cotton, B.A.; et al. Fibrinolysis Shutdown in Trauma: Historical Review and Clinical Implications. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 129, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medcalf, R.L.; Keragala, C.B.; Draxler, D.F. Fibrinolysis and the Immune Response in Trauma. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 46, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R.J.; Spinella, P.C.; Bochicchio, G.V. Tranexamic Acid Update in Trauma. Crit. Care Clin. 2017, 33, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.T.; Coleman, J.R.; Carmichael, H.; Mauffrey, C.; Vintimilla, D.R.; Samuels, J.M.; Sauaia, A.; Moore, E.E. High Rate of Fibrinolytic Shutdown and Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Severe Pelvic Fracture. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 246, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.H.; Koster, A.; Quinones, Q.J.; Milling, T.J.; Key, N.S. Antifibrinolytic Therapy and Perioperative Considerations. Anesthesiology 2018, 128, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meizoso, J.P.; Dudaryk, R.; Mulder, M.B.; Ray, J.J.; Karcutskie, C.A.; Eidelson, S.A.; Namias, N.; Schulman, C.I.; Proctor, K.G. Increased risk of fibrinolysis shutdown among severely injured trauma patients receiving tranexamic acid. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 84, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, L.S.; Vulliamy, P.; Gillespie, S.; Jones, T.F.; Pierre, R.S.J.; Breukers, S.E.; Gaarder, C.; Juffermans, N.P.; Maegele, M.; Stensballe, J.; et al. The S100A10 Pathway Mediates an Occult Hyperfibrinolytic Subtype in Trauma Patients. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, R.A.; Borrelli, M.R.; Vella-Baldacchino, M.; Thavayogan, R.; Orgill, D.P. The STROCSS statement: Strengthening the Reporting of Cohort Studies in Surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 46, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.J.; Gu, X.P.; Wu, X.D.; Chen, H.; Kwong, J.S.W.; Zhou, L.Y.; Chen, S.; Ma, Z.L. Restrictive Versus Liberal Strategy for Red Blood-Cell Transfusion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in Orthopaedic Patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 2018, 100, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.B. Estimating allowable blood loss: Corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology 1983, 58, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, S.B.; Hidalgo, J.H.; Bloch, T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery 1962, 51, 224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Hu, K.; Huang, W. Commentary: Tranexamic Acid in Patients Undergoing Coronary-Artery Surgery. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, L.; Cohen, E.; Vagher, J.; Woodward, E.; Caprini, J. Comparison of thrombelastography with common coagulation tests. Thromb. Haemost. 1981, 46, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Martini, W.; Dubick, M.; Salinas, J.; Butenas, S.; Kheirabadi, B.; Pusateri, A.; Vos, J.; Guymon, C.; Wolf, S.; et al. Thromboelastography as a better indicator of hypercoagulable state after injury than prothrombin time or activated partial thromboplastin time. J. Trauma 2009, 67, 266–275; discussion 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, S.; Cox, D. Thrombelastography. Br. J. Anaesth. 1992, 69, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salooja, N.; Perry, D. Thrombelastography. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis Int. J. Haemost. Thromb. 2001, 12, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.D.; Chen, Y.; Tian, M.; He, Y.; Tao, Y.Z.; Xu, W.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Huang, W. Application of thrombelastography (TEG) for safety evaluation of tranexamic acid in primary total joint arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madurska, M.J.; Sachse, K.A.; Jansen, J.O.; Rasmussen, T.E.; Morrison, J.J. Fibrinolysis in trauma: A review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. Off. Publ. Eur. Trauma Soc. 2018, 44, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.; Monroe, D.M. Coagulation 2006: A modern view of hemostasis. Hematol./Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.R.; Dahapute, A.A.; Panda, I.; Bava, S.S. Role of Local Infiltration of Tranexamic Acid in Reducing Blood Loss in Peritrochanteric Fracture Surgery in the Elderly Population. Malays. Orthop. J. 2016, 10, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Nilsoon, I.M.; Colleen, S.; Granstrand, B.; Melander, B. Role of urokinase and tissue activator in sustaining bleeding and the management thereof with EACA and AMCA. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1968, 146, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): An international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2105–2116. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, I.; Shakur, H.; Afolabi, A.; Brohi, K.; Coats, T.; Dewan, Y.; Gando, S.; Guyatt, G.; Hunt, B.J.; Morales, C.; et al. The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: An exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 1101.e1–1101.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, R.; Hocking, E.D.; Fearnley, G.R. Reaction pattern to three stresses--electroplexy, surgery, and myocardial infarction--of fibrinolysis and plasma fibrinogen. J. Clin. Pathol. 1969, 22, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.B.; Moore, E.E.; Chapman, M.P.; Hansen, K.C.; Cohen, M.J.; Pieracci, F.M.; Chandler, J.; Sauaia, A. Does Tranexamic Acid Improve Clot Strength in Severely Injured Patients Who Have Elevated Fibrin Degradation Products and Low Fibrinolytic Activity, Measured by Thrombelastography? J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 229, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Non-Fibrinolytic Shutdown (n = 88) | Fibrinolytic Shutdown (n = 150) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 36) | Group B (n = 52) | p Value | Group A (n = 70) | Group B (n = 80) | p Value | |

| Female, n (%) | 21 (58.3%) | 30 (57.7%) | 0.952 ┼ | 38 (54.3%) | 48 (60.0%) | 0.480 ┼ |

| Age, year (SD) | 60.38 (14.70) | 63.12 (17.88) | 0.096 * | 68.03 (15.67) | 68.72 (14.80) | 0.793 * |

| Height, cm (SD) | 159.38 (6.55) | 160.00 (7.47) | 0.726 * | 157.59 (6.12) | 159.65 (7.81) | 0.150 * |

| Weight, kg (SD) | 58.08 (8.09) | 59.79 (9.36) | 0.434 * | 59.43 (9.56) | 57.75 (11.54) | 0.423 * |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 22.89 (3.17) | 23.23 (3.29) | 0.667 † | 23.65 (3.17) | 22.59 (3.87) | 0.143 * |

| Major diagnosis | ||||||

| HF, n (%) | 12 (33.3%) | 13 (25.0%) | 0.473 ┼ | 25 (35.7%) | 23 (28.8%) | 0.362 ┼ |

| HOA, n (%) | 4 (11.1%) | 8 (15.4%) | 0.754 ┼ | 10 (14.3%) | 15 (18.8%) | 0.464 ┼ |

| DDH, n (%) | 9 (25.0%) | 12 (23.1%) | 0.835 ┼ | 18 (25.7%) | 19 (23.8%) | 0.781 ┼ |

| ONFH, n (%) | 11 (30.6%) | 19 (36.5%) | 0.560 ┼ | 17 (24.3%) | 23 (28.8%) | 0.537 ┼ |

| Left THA, n (%) | 22 (61.1%) | 31 (59.6%) | 0.888 ┼ | 31 (44.3%) | 41 (51.3%) | 0.394 ┼ |

| Intraoperative blood loss, mL (SD) | 138.70 (99.90) | 165.19 (156.42) | 0.141 * | 132.46 (117.45) | 157.39 (135.37) | 0.319 * |

| Operation time, min (SD) | 81.50 (33.81) | 84.79 (33.13) | 0.676 † | 96.93 (42.00) | 86.00 (36.80) | 0.122 * |

| LOS, day (SD) | 13.51 (5.45) | 14.02 (4.22) | 0.560 * | 13.26 (3.10) | 13.96 (3.88) | 0.315 * |

| Outcomes | Non-Fibrinolytic Shutdown (n = 88) | Fibrinolytic Shutdown (n = 150) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 36) | Group B (n = 52) | p Value | Group A (n = 70) | Group B (n = 80) | p Value | |

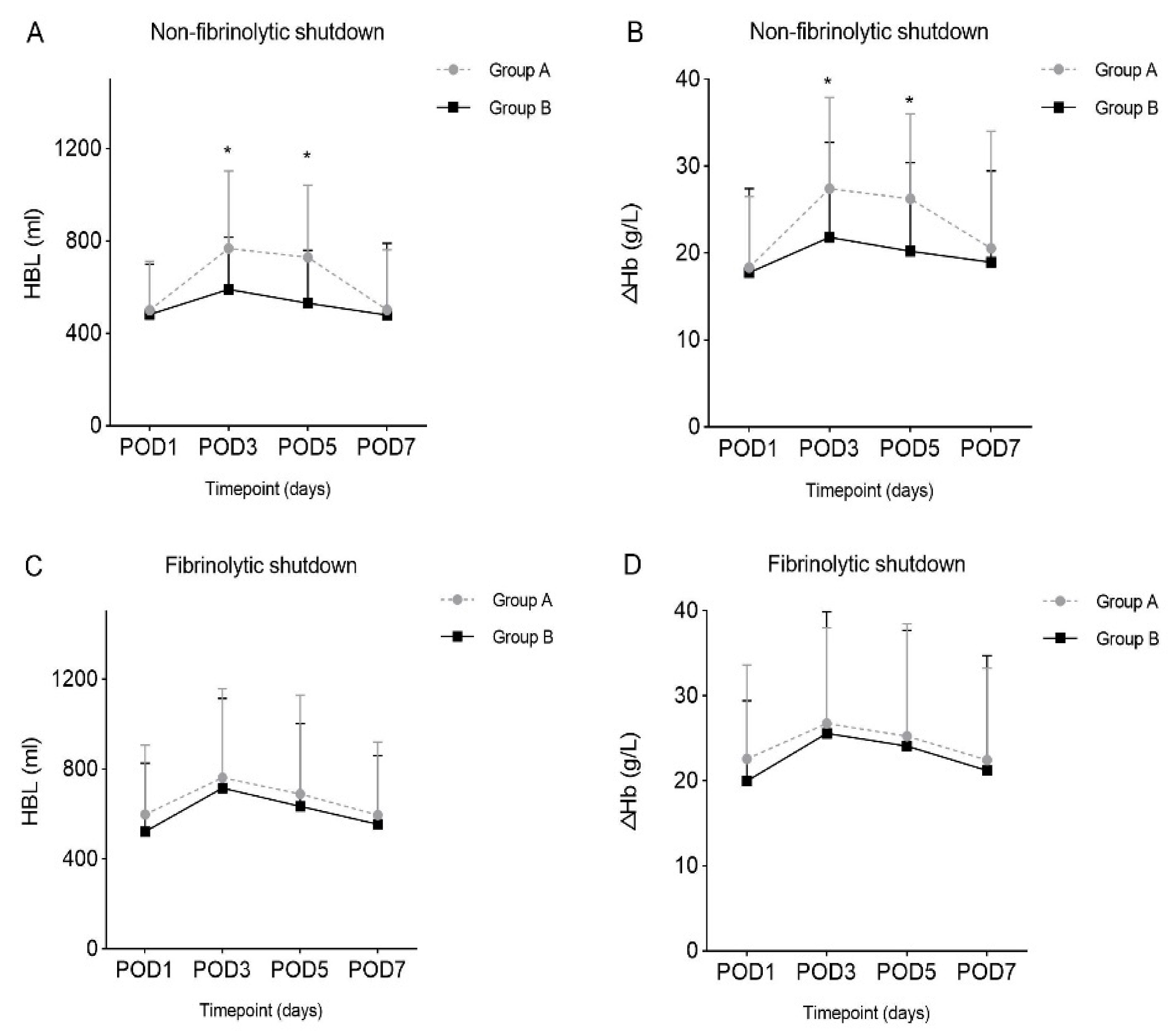

| HBL, mL (SD) | ||||||

| POD1 | 500.91 (211.17) | 481.46 (218.04) | 0.713 † | 597.92 (308.45) | 522.23 (304.26) | 0.230 * |

| POD3 | 768.10 (335.10) | 590.05 (227.15) | 0.009 *,§ | 761.87 (396.77) | 715.93 (398.98) | 0.572 † |

| POD5 | 729.34 (313.01) | 520.88 (227.88) | 0.003 *,§ | 689.53 (439.38) | 634.21 (368.88) | 0.275 * |

| POD7 | 501.48 (259.81) | 479.86 (310.61) | 0.864 * | 595.10 (325.65) | 553.80 (306.59) | 0.700 * |

| ΔHb, g/L (SD) | ||||||

| POD1 | 18.36 (8.16) | 17.75 (9.65) | 0.769 * | 22.57 (11.05) | 19.98 (9.45) | 0.167 * |

| POD3 | 27.42 (10.48) | 21.83 (10.92) | 0.027 †,§ | 26.75 (11.24) | 25.59 (14.30) | 0.623 * |

| POD5 | 26.25 (9.80) | 20.23 (10.19) | 0.033 †,§ | 25.25 (13.21) | 24.08 (13.65) | 0.666 † |

| POD7 | 20.55 (13.46) | 18.94 (10.51) | 0.723 * | 22.46 (10.79) | 21.20 (13.50) | 0.767 * |

| Outcomes | Non-Fibrinolytic Shutdown (n = 88) | Fibrinolytic Shutdown (n = 150) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 36) | Group B (n = 52) | p Value | Group A (n = 70) | Group B (n = 80) | p Value | |

| D-D, mg/L (SD) | ||||||

| POD1 | 4.50 (1.99) | 4.08 (4.04) | 0.743 * | 5.57 (3.24) | 3.80 (3.65) | 0.052 * |

| POD3 | 2.30 (1.16) | 1.64 (1.43) | 0.164 * | 2.03 (1.57) | 1.60 (1.36) | 0.252 * |

| POD5 | 6.82 (7.33) | 5.59 (5.39) | 0.283 * | 4.38 (2.19) | 3.76 (2.06) | 0.328 † |

| POD7 | 4.30 (0.19) | 3.94 (2.50) | 0.846 * | 5.80 (3.61) | 3.84 (1.85) | 0.174 * |

| FDP, μg/mL (SD) | ||||||

| POD1 | 12.34 (3.52) | 10.08 (7.26) | 0.324 * | 13.15 (8.37) | 10.44 (8.81) | 0.222 * |

| POD3 | 7.60 (2.76) | 6.27 (6.41) | 0.508 * | 6.91 (3.50) | 6.39 (5.40) | 0.699 * |

| POD5 | 10.80 (7.38) | 10.07 (3.38) | 0.801 * | 12.13 (4.89) | 11.38 (5.24) | 0.607 † |

| POD7 | 12.00 (5.24) | 11.40 (1.56) | 0.876 * | 14.70 (9.76) | 11.86 (5.07) | 0.465 * |

| PT, s (SD) | ||||||

| POD1 | 13.73 (1.21) | 13.78 (0.84) | 0.872 * | 13.75 (0.65) | 13.88 (0.89) | 0.558 * |

| POD3 | 14.25 (2.14) | 13.86 (1.06) | 0.382 * | 13.79 (0.99) | 13.76 (0.95) | 0.923 † |

| POD5 | 13.60 (2.19) | 13.72 (0.81) | 0.794 * | 13.21 (0.94) | 13.46 (1.04) | 0.413 * |

| POD7 | 14.15 (0.64) | 13.90 (1.19) | 0.776 * | 12.25 (0.21) | 13.77 (1.34) | 0.122 * |

| APTT, s (SD) | ||||||

| POD1 | 36.83 (5.51) | 36.78 (4.89) | 0.978 * | 36.33 (5.10) | 38.31 (5.38) | 0.147 † |

| POD3 | 41.23 (6.33) | 41.70 (7.68) | 0.850 * | 40.77 (5.48) | 43.72 (7.33) | 0.133 * |

| POD5 | 40.24 (5.72) | 41.49 (6.20) | 0.621 * | 38.85 (4.89) | 41.55 (6.60) | 0.140 * |

| POD7 | 42.85 (8.41) | 40.16 (5.16) | 0.507 * | 34.25 (4.03) | 40.77 (5.02) | 0.082 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Chen, B.; Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Zuo, X.; Lei, Y.; Huang, W. Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients with Distinct Postoperative Fibrinolytic Phenotypes Require Different Antifibrinolytic Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236897

Liu J, Chen B, Wu X, Wang H, Zuo X, Lei Y, Huang W. Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients with Distinct Postoperative Fibrinolytic Phenotypes Require Different Antifibrinolytic Strategies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(23):6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236897

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiacheng, Bowen Chen, Xiangdong Wu, Han Wang, Xiaohai Zuo, Yiting Lei, and Wei Huang. 2022. "Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients with Distinct Postoperative Fibrinolytic Phenotypes Require Different Antifibrinolytic Strategies" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 23: 6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236897

APA StyleLiu, J., Chen, B., Wu, X., Wang, H., Zuo, X., Lei, Y., & Huang, W. (2022). Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients with Distinct Postoperative Fibrinolytic Phenotypes Require Different Antifibrinolytic Strategies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(23), 6897. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11236897