Abstract

(1) Background: This study aimed to investigate the relationship of triglyceride glucose–body mass index (TyG-BMI) with bone mineral density (BMD), femoral neck geometry, and risk of fracture in middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals. (2) Methods: A total of 832 nondiabetic individuals were selected from the prospective population-based HOPE cohort. All individuals underwent DXA for assessment of BMD at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip, as well as femoral neck geometry. The 10-year probabilities of both major osteoporotic (MOFs) and hip fractures (HFs) were calculated. (3) Results: Cortical thickness, compression strength index, cross-sectional moment of inertia, cross-sectional area, section modulus, and 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in women (all p < 0.001). The presence of osteoporosis was related to age, BMI, BMD and femoral neck geometry, TyG-BMI, MOF, and HF. TyG-BMI was positively correlated with BMD. In men, TyG-BMI showed significant negative correlation with HF but not with MOF, the correlation exists only after adjusting for other variables in women. Femoral neck geometries were significantly impaired in individuals with low TyG-BMI. (4) Conclusion: TyG-BMI is positively associated with BMD and geometry, and negatively associated with risk of fracture in nondiabetic middle-aged and elderly Chinese men and women.

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with resulting increased bone fragility and high risk of fracture []. It is a major contributor to the global burden of disease, and early recognition and management will benefit both individuals and society. Bone mineral density (BMD), determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), is currently widely used to assess the quality of bone. However, only 50–70% of total bone strength can be attributed to BMD. Previous research has shown that some patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity have high fracture risk despite having high BMD [,,,]. Independent of BMD, bone geometry contributes to fracture risk [,,]. Geometric parameters of the femoral neck, such as cross-sectional area (CSA), buckling ratio (BR), and section modulus (SM) [] also describe bone strength and are independently predictive of hip fragility fracture [,,].

Insulin resistance (IR) does not seem to have a detrimental effect on bone mass, the most important parameter for the diagnosis of osteoporosis [,]. Animal research suggest that insulin exerts an anabolic effect on bone and is a critical regulator of skeletal development and structural integrity [,]. In the Rotterdam Study, which enrolled nearly 6000 elderly men and women, higher glucose and insulin levels were associated with higher bone mass at all skeletal sites, supporting the association between increased insulin levels and high BMD []. Abrahamsen and colleagues [], however, found no association between BMD and insulin, but this may have been due to the relatively small population studied. In addition to BMD, femoral neck geometry affects bone strength. Studies have reported an inverse association between femoral neck strength and IR [], but the study populations included individuals with and without diabetes. Shanbhogue et al. [] reported that hyperinsulinemia directly affects bone structure, independent of obesity, in nondiabetic postmenopausal women. A few studies have examined the relationship between insulin resistance and osteoporosis in nondiabetic patients. Francisco et al. [] conducted research in nondiabetic postmenopausal women and showed that there is a direct relationship between IR and BMD, but no association between IR and the prevalence of osteoporosis. It is possible that the relationship between IR and bone metabolism varies with sex, race, and bone mass or structure.

IR was earlier evaluated by the pancreatic suppression test, the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp technique (HEGC), or the minimal model approximation of the metabolism of glucose [,,]. However, these methods are invasive, complicated, expensive, and difficult to use in the clinical setting. Meanwhile, the homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), which is mostly used nowadays, is limited by the absence of consensus on the reference value. Recently, the triglyceride and glucose–body mass index (TyG-BMI)—which incorporates fasting blood glucose, serum triglyceride levels, and body mass index (BMI)—has been proposed as a reliable and highly sensitive and specific alternative marker of IR [,]. Several studies have shown that high TyG-BMI is associated with cardiovascular events [] and incident nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a healthy population [], and Khamseh et al. found that TyG-BMI is a reliable discriminator of liver fibrosis []. However, to date, no clinical studies have examined the association between TyG-BMI and bone metabolism. This study aimed to investigate how TyG-BMI is related to BMD, femoral neck geometry, and risk of fracture in nondiabetic Chinese middle-aged and elderly individuals.

2. Patients and Methods

The study population was selected from among the participants of the HOPE study, an ongoing prospective study that is enrolling individuals undergoing physical examination at the Health Management Center of Xiangya Second Hospital. The HOPE study, which aims to achieve a sample size of 5000 over a period of 1 year, has already accumulated more than 1800 patients. Patients are eligible for enrollment in the HOPE study if they (1) are ≥40 years old and (2) undergo DXA for BMD measurement. The exclusion criteria are (1) history of hip joint replacement or lumbar spine surgery; (2) inability to undergo DXA for any reason; (3) history of treatment with antiosteoporosis drugs; or (4) history of malignant tumor.

For the present study, we selected 832 healthy postmenopausal women and men aged ≥50 years from the HOPE cohort. We excluded patients with diabetes mellitus and individuals without data on fasting blood glucose or serum triglycerides. The medical records of the selected patients were searched to obtain details such as age, years since menopause, investigation results, height, and weight. BMI was calculated as the ratio of weight (in kilograms) and height (in meters) squared (kg/m2). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Second Hospital, South China University, Changsha, China (approved number LYF2021015).

DXA scans were performed by two experienced physicians using the bone densitometer (Discovery Wi S/N87556; Hologic, Marlborough, MA, USA). The quality control (QC) program at a DXA facility includes adherence to manufacturer guidelines for system maintenance. In addition, reliability analysis was according The International Society for Clinical Densitometry guideline. The regions scanned were the left femoral neck, total hip, and lumbar spine. Seven hip geometric parameters were calculated: outer diameter, CSA, cortical thickness (CT), cross-sectional moment of inertia (CSMI), compression strength index (CSI), SM and BR (from BMD), and areal bone size data. Outer diameter refers to the outer diameter of the femoral neck at its midpoint. Endocortical diameter refers to the endocortical diameter of the femoral neck at the midpoint. CSA is an index of axial compression strength and reflects the resistance to loads directed along the bone axis. CSMI is a measure of the mass distribution relative to the geometric center; it reflects how effective a cross-section is at resisting bending and torsion—depending on the axis chosen for calculation. CT is an estimate of mean cortical thickness. BR is an index of bone geometric instability and reflects the resistance against compressive stress, which could lead to sudden sideways deflection of the structural member; higher BR values indicate greater instability and higher fracture risk [,,]. CSI is a measure of the ability of the femoral neck to withstand compressive load in the axial dimension. SM, computed as CSMI divided by the distance from the bone edge to the centroid, describes femoral neck bending strength. A China-specific fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) algorithm (which included the femoral neck BMD T-score) was used to determine the 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fractures (MOFs) and hip fractures (HFs).

Blood samples were obtained after enrollment and overnight fast of at least 8 h. Fasting blood glucose, serum triglycerides, serum total cholesterol, and serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were measured using an ADVIA 1650 Chemistry Analyzer (Siemens, Washington, DC, USA), and a Hitachi 7600 Automatic Analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Serum levels of total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) were measured by an automated chemiluminescence system. TyG-BMI was calculated using the formula [] TyG-BMI = Ln [fasting glucose (mg/dL) × triglycerides (mg/dL)/2] × BMI.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were assessed for normality and analyzed using the independent samples t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Pearson or Spearman correlation was used to examine associations between TyG-BMI and BMD, femoral neck geometry, and risk of fracture. Participants were stratified by sex to examine sex-specific associations. Multivariable linear regression analysis was used to explore associations between TyG-BMI and femoral neck parameters (bone density and femoral neck geometry) in the two sexes. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to explore associations between TyG-BMI and osteoporosis. All analyses were performed using SPSS 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

Characteristics of the 832 individuals (474 men, 358 women) are summarized in Table 1 and Table S1. Mean age was comparable between men and women (59.0 ± 7.95 years vs. 59.6 ± 7.72 years, p = 0.126). Mean TyG-BMI was significantly higher in men than in women (219.6 ± 32.5 vs. 202.5 ± 29.8, p < 0.001). The prevalence of osteoporosis (as diagnosed by the BMD T-score) was higher in women than in men (20.1% vs. 9.5%, p < 0.05). Other detailed baseline characteristics are presented in Table S1. Compared to the nonosteoporotic group, the presence of osteoporosis was related to age, BMI, BMD and femoral neck geometry, TyG-BMI and TyG index, MOF, and HF in both sexes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of osteoporosis and nonosteoporosis group.

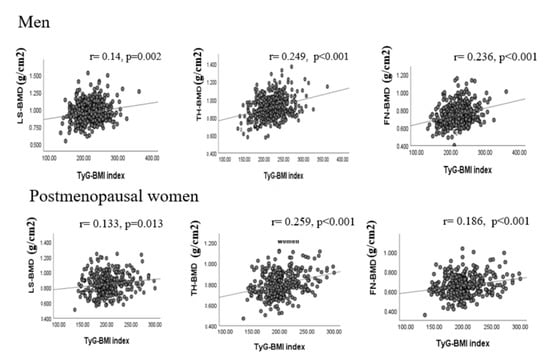

3.2. Association of TyG-BMI with BMD

Figure 1 shows the correlation of TyG-BMI with BMD at different sites. In men, TyG-BMI was positively correlated with femoral neck BMD (r = 0.236, p < 0.001), total hip BMD (r = 0.249, p < 0.001), and lumbar spine BMD (r = 0.145, p = 0.002). Similarly, in women, TyG-BMI was positively correlated with femoral neck BMD (r = 0.186, p < 0.001), total hip BMD (r = 0.259, p < 0.001), and lumbar spine BMD (r = 0.133, p = 0.013). In both sexes, the association persisted even after adjusting for age, smoking, drinking, and history of previous hip fracture or parental hip fracture.

Figure 1.

Correlations of serum TyG-BMI level with BMD. FN: femoral neck; TH: total hip; LS: lumbar spine; BMD: bone mineral density; TyG: triglyceride glucose index, TyG-BMI: combined TyG and BMI.

In unadjusted analysis (Table 2), TyG-BMI was positively correlated with femoral neck CSA, CSMI, SM, and CT in both men and women (all p < 0.001), but negatively correlated with BR and CSI. In both sexes, the associations remained statistically significant even after adjusting for age, smoking, drinking, and history of previous hip fracture or parental hip fracture (Table 3). In men, TyG-BMI was significantly correlated to HF but not to MOF; in women, TyG-BMI was not significantly correlated with either of the two factors (p > 0.05). However, in women, after adjusting for age, smoking, drinking, and history of previous hip fracture and parental hip fracture, TyG-BMI was significantly associated with MOF and HF; in men, the TyG-BMI remained significantly associated with HF.

Table 2.

Correlations of triglyceride glucose–body mass index and bone strength and risk of fracture.

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis between the TyG-BMI and the densitometry parameters.

3.3. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis of Association between TyG-BMI and BMD and Bone Geometric Parameters

Linear regression analysis showed that TyG-BMI was a significant independent predictor of BMD, SM, CSA, CSI, and BR. The standardized regression coefficients of TyG-BMI in men (Table 3) and women (Table 4), respectively, were 0.234 (p < 0.001) and 0.279 (p < 0.001) for femoral neck BMD, 0.176 (p < 0.001) and 0.192 (p < 0.001) for total hip BMD, 0.238 (p < 0.001) and 0.283 (p < 0.001) for CSA, 0.212 (p < 0.001) and 0.228 (p < 0.001) for SM, and −0.202 (p < 0.001) and 0.282 (p < 0.001) for BR.

Table 4.

Linear regression analysis between the TyG-BMI and the densitometry parameters.

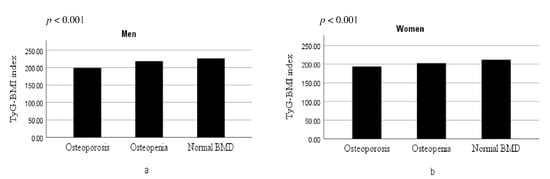

3.4. Distributions of the TyG-BMI According to the Bone Health Status

In the evaluation of the relationship between TyG-BMI and the bone health status, patients with osteoporosis had a lower TyG-BMI (p for trend = 0.006) compared to the others, showing a dose–response behavior (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distributions of the TyG-BMI according to the bone health status in men (a) and in women (b).

3.5. Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses between Possible Predictors and Osteoporosis

In the multivariable logistic regression analyses, the TyG-BMI was found to be significantly associated with osteoporosis (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.019; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.01–1.028) after adjusting for confounders. Age (aOR = 0.919; 95% CI = 0.892–0.947) and sex, female (aOR = 0.489; 95% CI = 0.266–0.889) were also related to osteoporosis (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses between possible predictors and osteoporosis. Adjusted with age, sex, 25(OH)D, current smoker, current drinker.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the association of TyG-BMI with bone mass and femoral neck geometry in healthy, nondiabetic, middle-aged and elderly individuals. The proximal femur, hip, and the lumbar spine were examined, as these are anatomical sites at high risk of osteoporotic fractures. As measures of bone strength, we used areal BMD (aBMD) and femoral geometry. TyG-BMI, which combines serum triglycerides, fasting plasma glucose, and obesity status, is considered more reliable than TyG for the identification of IR. It is a less expensive and more reliable marker of IR than traditional markers such as HOMA-IR [,]. Although IR cannot replace DXA in the diagnosis of osteoporosis, IR is introduced as a simple indicator, which can reflect the level and change in BMD. In addition, it can help to specify a reasonable lipid and FBG control target for nondiabetic individuals, because IR is known to have a deleterious effect on metabolic status, but this study found that it may have a protective effect on bone mineral density. In the future, we will further explore a reasonable range of lipids and FBG to achieve the greatest benefit.

We demonstrated that higher aBMD was associated with higher bone strength and lower fracture risk at all sites, with the association being significantly stronger in men than in postmenopausal women. The sex differences in these parameters may explain the higher incidence of fragility fractures in women. It also implies that sex-dependent femoral neck geometry contributes significantly to the ability to withstand stress.

The relationship between IR and BMD has been studied in different populations but the results have been mixed. Consistent with Riggs et al. [], we found that higher TyG-BMI was associated with greater aBMD at both weight-bearing and nonweight-bearing skeletal sites, and TyG-BMI was significantly associated with osteoporosis. Previous studies have reported an association between bone metabolism and HOMA-IR, another surrogate marker of IR. Further, greater IR was found to be associated with higher BMD [,]. A study of Caucasian nondiabetic women from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) found that higher IR is associated with greater volumetric BMD and generally favorable bone microarchitecture at nonweight-bearing distal radius and weight-bearing distal tibia, independent of body weight []. This effect of hyperinsulinism on BMD may be because insulin exerts peripheral osteogenic effects via stimulation of osteoblasts or inhibition of osteoclasts. All these research results suggest that TyG-BMI is a protective factor for osteoporosis. However, Shin et al. [] reported an inverse relationship between HOMA-IR and aBMD in a population-based study of young South Korean men (mean age, 49.9 years) suggesting that IR is a negative predictor of bone health. Our study population differs from that of Shin et al. [] in several aspects: our study participants were Chinese, older (mean age, 60.3 years), and, importantly, nondiabetic. It is currently unknown whether the effects of IR or hyperinsulinemia on bone are age-, sex-, or race-specific. The inclusion of patients with diabetes in Shin et al. [] may have confounded their results as HOMA-IR is unreliable in patients on antidiabetic medications; further, chronic hyperglycemia and/or antidiabetic medications may affect skeletal microarchitecture. Thus, comparison of their findings with ours is difficult.

In this study, we also investigated the association between TyG-BMI and femoral neck geometry. A recent study showed that several conditions associated with altered bone metabolism (for example, sarcopenia) result in poor femoral neck geometry, suggesting that these indices on DXA scans may be a good indicator of bone health []. Consistent with a previous Chinese study [], we found that CSA, CT, SM, CSMI, and CSI decrease with age, whereas BR increases with age. These results imply that the decrease in CSA, CT, SM, CSMI, and CSI and increase in BR might contribute to fragility fractures of the femoral neck in old age. Further, CSA, CT, SM, CSMI, and CSI were lower, and BR higher, in women than in men, which may explain the greater vulnerability of the femoral neck in the former.

There is a paucity of data describing the relationships between IR and femoral neck geometry. In the present study, TyG-BMI was positively associated with femoral neck CSA and SM, but negatively associated with BR; the relationships remained statistically significant even after controlling for age and previous fracture, suggesting that IR contributed to favorable femoral neck geometry. A possible explanation for this relationship is that insulin has an anabolic effect on bone, stimulating osteoblast growth and proliferation on periosteal surfaces and thus increasing SM and CSA. Overall, the results suggest that TyG-BMI has a positive effect on bone geometry in middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals. Contrary to our findings, an inverse association between IR and bone size has been demonstrated in nondiabetic postmenopausal Caucasian women []. In Korean men and women, with and without diabetes, HOMA-IR and fasting insulin levels were found to be inversely associated with composite indices of femoral neck strength []. The primary difference between our study and the studies mentioned above is in the populations enrolled, implying that differences in sex, age, diabetes status, and race affect the relationship between IR and bone structure.

This study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, so we cannot infer that IR leads to high bone strength; that will have to be clarified in longitudinal studies. Second, serum levels of hormones that affect bone metabolism (e.g., estrogen, androgen, and pituitary gonadotropin) were not evaluated in our study. Third, we did not use the HEGC technique and HOMA-IR for measuring IR, these methods, although accurate and popular, are time-consuming and costly and therefore not suitable for application in large samples. TyG-BMI is a reliable and highly sensitive alternative to HEGC [] and HOMA-IR in nondiabetic individuals []. In addition, the results are only applicable to middle-aged and elderly nondiabetic Chinese individuals. Other populations need to be studied further.

In summary, TyG-BMI may be a reliable indicator of favorable bone density and strength in healthy, nondiabetic postmenopausal women and men and could be useful in the clinic to evaluate and predict the risk of osteoporosis. Possible mechanisms are as follows: physiological concentrations of insulin have been shown to inhibit osteoclast activity in bone and to increase osteoblast proliferation rate, collagen synthesis, alkaline phosphatase production, and glucose uptake. Insulin-deficient models are associated with reductions in mineralized surface area, osteoid surface, mineral apposition rate, and osteoblast activity and number []. Studies in murine models suggest that hyperinsulinemia and IR, in the absence of hyperglycemia, may contribute to reduced bone turnover, and reduced bone turnover may increase areal BMD []. IR and hyperinsulinemia can exist in both diabetic and nondiabetic people. In nondiabetic people who have IR and hyperinsulinemia, the risk of developing diabetes in the later stage is greatly increased. Additionally, IR and hyperinsulinemia are major cardiovascular risk factors in healthy persons and patients with diabetes []. However, considering the impact of IR on bone, it is particularly necessary to find an optimal cut point value. More mechanistic studies, both preclinical and clinical, are needed to better understand the effect of IR on bone and metabolism, and to clarify whether insulin resistance-related changes affect fracture risk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm11195694/s1, Table S1: Baseline characteristics of participants according to gender.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S. and H.L.; data curation, Z.W., Y.L., L.X., Q.W., R.C., N.D., X.Q. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, Z.W., L.X., C.Y., Q.W., R.C., Y.O. and Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.L., Z.S. and H.L.; project administration, H.L.; software, C.Y. and Y.O.; supervision, H.L.; validation, R.C.; writing—original draft, Z.W., N.D. and X.Q.; writing—review & editing, Z.S. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant number 81870622), the Hunan Nature Science Foundation (grant number 2018JJ2574), the Changsha Nature Science Foundation (grant number kq2014251), and Bethune Charitable Foundation, BCF (grant number G-X-2019-1107-3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of (protocol code IT202012) on 26 February 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AGE | glycation end product |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BR | buckling ratio |

| CSA | cross-sectional area |

| CSI | compression strength index |

| CSMI | cross-sectional moment of inertia |

| CT | cortical thickness |

| DXA | dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| HEGC technique | hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp technique |

| HFs | hip fractures |

| HOMA-IR | homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance |

| IR | insulin resistance |

| MOFs | major osteoporotic fractures |

| SM | section modulus |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TyG-BMI | triglyceride and glucose–body mass index |

References

- Kado, D.; Browner, W.; Blackwell, T.; Gore, R.; Cummings, S.R. Rate of bone loss is associated with mortality in older women: A prospective study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2000, 15, 1974–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonds, D.; Larson, J.; Schwartz, A.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Robbins, J.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Johnson, K.C.; Margolis, K.L. Risk of fracture in women with type 2 diabetes: The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 3404–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestergaard, P.J. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes—A meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2007, 18, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siris, E.S.; Chen, Y.-T.; Abbott, T.A.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Miller, P.D.; Wehren, L.E.; Berger, M.L. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, K.L.; Seeley, D.G.; Lui, L.-Y.; Cauley, J.A.; Ensrud, K.; Browner, W.S.; Cummings, S.R. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: Long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2003, 18, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.G.; Curiel, M.D.; Carranza, F.H.; Cano, R.P.; Peréz, A.D. Femoral bone mineral density, neck-shaft angle and mean femoral neck width as predictors of hip fracture in men and women. Multicenter Project for Research in Osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2000, 11, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laet, C.; Kanis, J.A.; Odén, A.; Johanson, H.; Johnell, O.; Delmas, P.; Eisman, J.A.; Kroger, H.; Fujiwara, S.; Garnero, P. Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, P.; Partanen, J.; Jalovaara, P.; Jämsä, T. Combination of bone mineral density and upper femur geometry improves the prediction of hip fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 2004, 15, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.M.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Marshall, L.M.; Cummings, S.R.; Lang, T.F.; Cauley, J.A.; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Research Group. Proximal femoral structure and the prediction of hip fracture in men: A large prospective study using QCT. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, M.E.; Beck, T.J.; Lian, Y.; Karlamangla, A.S.; Greendale, G.A.; Ruppert, K.; Lo, J.; Greenspan, S.; Vuga, M.; Cauley, J.A. Ethnic variability in bone geometry as assessed by hip structure analysis: Findings from the hip strength across the menopausal transition study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, B.C.; Lewis, J.R.; Brown, K.; Prince, R.L. Evaluation of a simplified hip structure analysis method for the prediction of incident hip fracture events. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwic, A.E.; Clynes, M.; Denison, H.J.; Jameson, K.A.; Edwards, M.H.; Sayer, A.A.; Dennison, E.M. Non-invasive Assessment of Lower Limb Geometry and Strength Using Hip Structural Analysis and Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography: A Population-Based Comparison. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2016, 98, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Conte, C.; Epstein, S.; Napoli, N. Insulin resistance and bone: A biological partnership. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paula, F.J.; de Araújo, I.M.; Carvalho, A.L.; Elias, J., Jr.; Salmon, C.E.; Nogueira-Barbosa, M.H. The Relationship of Fat Distribution and Insulin Resistance with Lumbar Spine Bone Mass in Women. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, J.S.; Kalaitzoglou, E.; Clay Bunn, R.; Uppuganti, S.; Thrailkill, K.M.; Fowlkes, J.L. Preserving and restoring bone with continuous insulin infusion therapy in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Bone Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrailkill, K.; Bunn, R.C.; Lumpkin CJr Wahl, E.; Cockrell, G.; Morris, L.; Kahn, C.R.; Fowlkes, J.; Nyman, J.S. Loss of insulin receptor in osteoprogenitor cells impairs structural strength of bone. J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 703589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolk, R.P.; Van Daele, P.L.; Pols, H.A.; Burger, H.; Hofman, A.; Birkenhäger, J.C.; Grobbee, D.E. Hyperinsulinemia and bone mineral density in an elderly population: The Rotterdam Study. Bone 1996, 18, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsen, B.; Rohold, A.; Henriksen, J.E.; Beck-Nielsen, H. Correlations between insulin sensitivity and bone mineral density in non-diabetic men. Diabet. Med. 2000, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanthan, P.; Crandall, C.J.; Miller-Martinez, D.; Seeman, T.E.; Greendale, G.A.; Binkley, N.; Karlamangla, A.S. Insulin resistance and bone strength: Findings from the study of midlife in the United States. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhogue, V.V.; Finkelstein, J.S.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Yu, E.W. Association between Insulin Resistance and Bone Structure in Nondiabetic Postmenopausal Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3114–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo-Sánchez, F.; Usategui-Martín, R.; Ruiz-de Temiño, Á.; Gil, J.; Ruiz-Mambrilla, M.; Fernández-Gómez, J.M.; Pérez-Castrillón, J.L. Relationship between Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), Trabecular Bone Score (TBS), and Three-Dimensional Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (3D-DXA) in Non-Diabetic Postmenopausal Women. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Tobin, J.D.; Andres, R. Glucose clamp technique: A method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am. J. Physiol. 1979, 237, E214–E223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, R.N.; Prager, R.; Volund, A.; Olefsky, J.M. Equivalence of the insulin sensitivity index in man derived by the minimal model method and the euglycemic glucose clamp. J. Clin. Investig. 1987, 79, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, M.S.; Doberne, L.; Kraemer, F.; Tobey, T.; Reaven, G. Assessment of insulin resistance with the insulin suppression test and the euglycemic clamp. Diabetes 1981, 30, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Romero, F.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; González-Ortiz, M.; Martínez-Abundis, E.; Ramos-Zavala, M.G.; Hernández-González, S.O.; Rodríguez-Morán, M. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3347–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, B.; Kim, W.; Ahn, C.; Choi, H.Y.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, J.; Shin, H.; Kang, J.G.; Moon, S. Lipid indices as simple and clinically useful surrogate markers for insulin resistance in the U.S. population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Dong, L.; Shao, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Lv, S.; Sun, Y.; Shen, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X. Triglyceride glucose index for predicting cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitae, A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hamaguchi, M.; Obora, A.; Kojima, T.; Fukui, M. The Triglyceride and Glucose Index Is a Predictor of Incident Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 2019, 5121574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamseh, M.E.; Malek, M.; Abbasi, R.; Taheri, H.; Lahouti, M.; Alaei-Shahmiri, F. Triglyceride Glucose Index and Related Parameters (Triglyceride Glucose-Body Mass Index and Triglyceride Glucose-Waist Circumference) Identify Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver and Liver Fibrosis in Individuals with Overweight/Obesity. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2021, 19, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, D.; Lee, T. Assessing bone quality in terms of bone mineral density, buckling ratio and critical fracture load. J. Bone Metab. 2014, 21, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sheu, Y.; Cauley, J.A.; Patrick, A.L.; Wheeler, V.W.; Bunker, C.H.; Zmuda, J.M. Risk factors for fracture in middle-age and older-age men of African descent. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Beck, T.J.; Wang, X.F.; Seeman, E. Structural and biomechanical basis of sexual dimorphism in femoral neck fragility has its origins in growth and aging. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2003, 18, 1766–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Er, L.K.; Wu, S.; Chou, H.H.; Hsu, L.A.; Teng, M.S.; Sun, Y.C.; Ko, Y.L. Triglyceride Glucose-Body Mass Index Is a Simple and Clinically Useful Surrogate Marker for Insulin Resistance in Nondiabetic Individuals. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locateli, J.C.; Lopes, W.A.; Simões, C.F.; de Oliveira, G.H.; Oltramari, K.; Bim, R.H.; Nardo, N., Jr. Triglyceride/glucose index is a reliable alternative marker for insulin resistance in South American overweight and obese children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 32, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, B.L.; Melton, L.J., III; Robb, R.A.; Camp, J.J.; Atkinson, E.J.; Peterson, J.M.; Rouleau, P.A.; McCollough, C.H.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Khosla, S. Population-based study of age and sex differences in bone volumetric density, size, geometry, and structure at different skeletal sites. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 1945–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimeri, M.; Leek, F.; Wang, N.X.; Koh, H.R.; Roy, N.C.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Totman, J.J. Association of Insulin Resistance with Bone Strength and Bone Turnover in Menopausal Chinese-Singaporean Women without Diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Hong, A.R.; Choi, W.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Kang, H.C. Association of Triglyceride-Glucose Index with Bone Mineral Density in Non-diabetic Koreans: KNHANES 2008-2011. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2021, 108, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, K.; Park, S.M. Association between insulin resistance and bone mass in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddik, H.; Nasr, R.; Pinti, A.; Watelain, E.; Fayad, I.; Baddoura, R.; El Hage, R. Sarcopenia negatively affects hip structure analysis variables in a group of Lebanese postmenopausal women. BMC Bioinform. 2020, 21 (Suppl. S2), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Tang, M.L.; Wu, X.P.; Yuan, L.Q.; Dai, R.C.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, Z.-F.; Peng, Y.-Q.; Luo, X.-H.; Wu, X.-Y. Gender differences in a reference database of age-related femoral neck geometric parameters for Chinese population and their association with femoral neck fractures. Bone 2016, 93, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, B.-J.; Lee, S.H.; Koh, J.M. Insulin resistance and composite indices of femoral neck strength in Asians: The fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV). Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 84, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrailkill, K.M.; Lumpkin, C.K., Jr.; Bunn, R.C.; Kemp, S.F.; Fowlkes, J.L. Is insulin an anabolic agent in bone? Dissecting the diabetic bone for clues. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 289, E735–E745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, D.; Baxter, B.; Campbell, B.C.V.; Carpenter, J.S.; Cognard, C.; Dippel, D.; Vorwerk, D. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Revised Consensus Statement for Endovascular Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Int. J. Stroke 2018, 13, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeva-Andany, M.M.; Martínez-Rodríguez, J.; González-Lucán, M.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Castro-Quintela, E. Insulin resistance is cardiovascular risk factor in humans. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).