Impact of Prior Statin Therapy on In-Hospital Outcome of STEMI Patients Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Protocol

2.3. Statistical Analysis

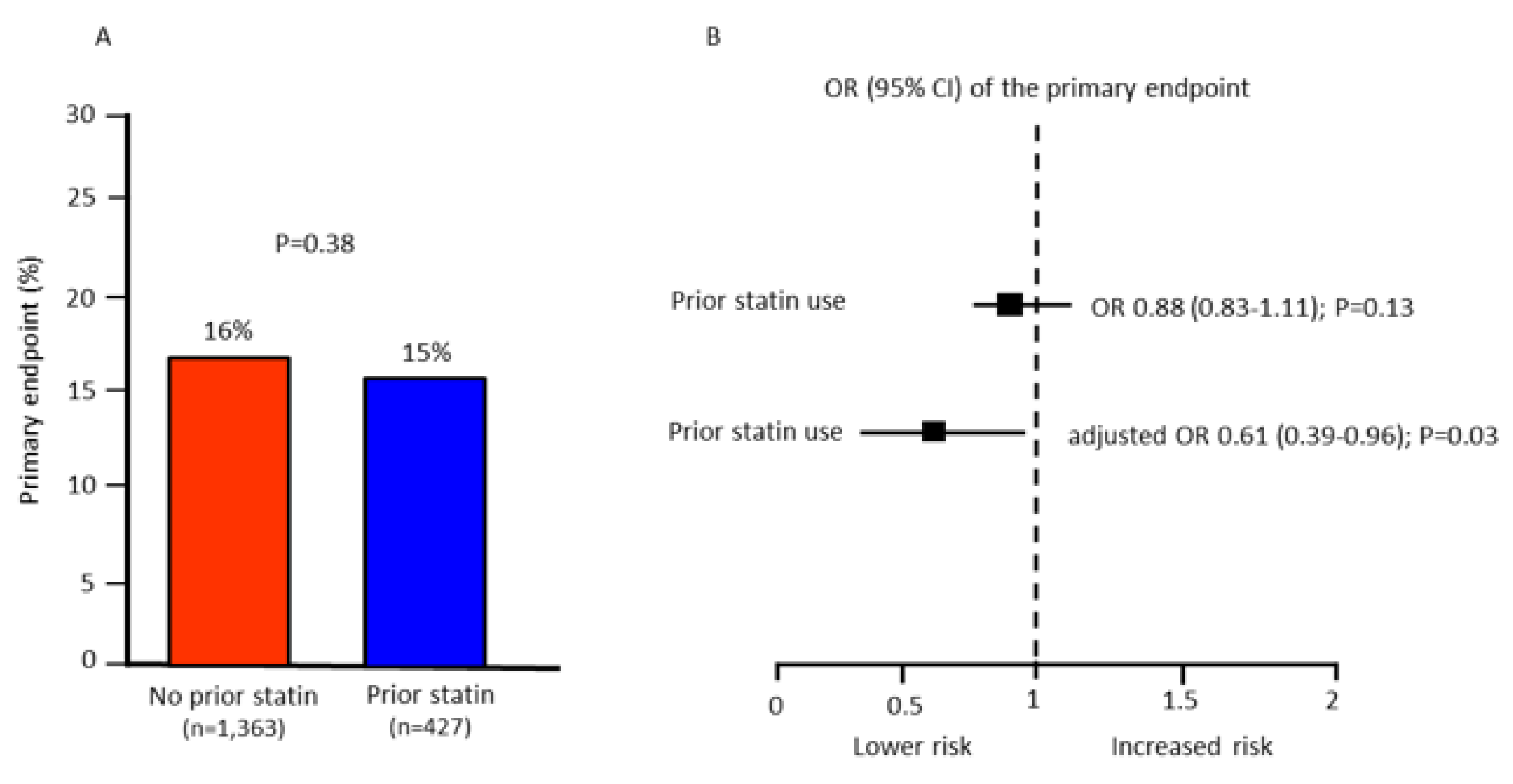

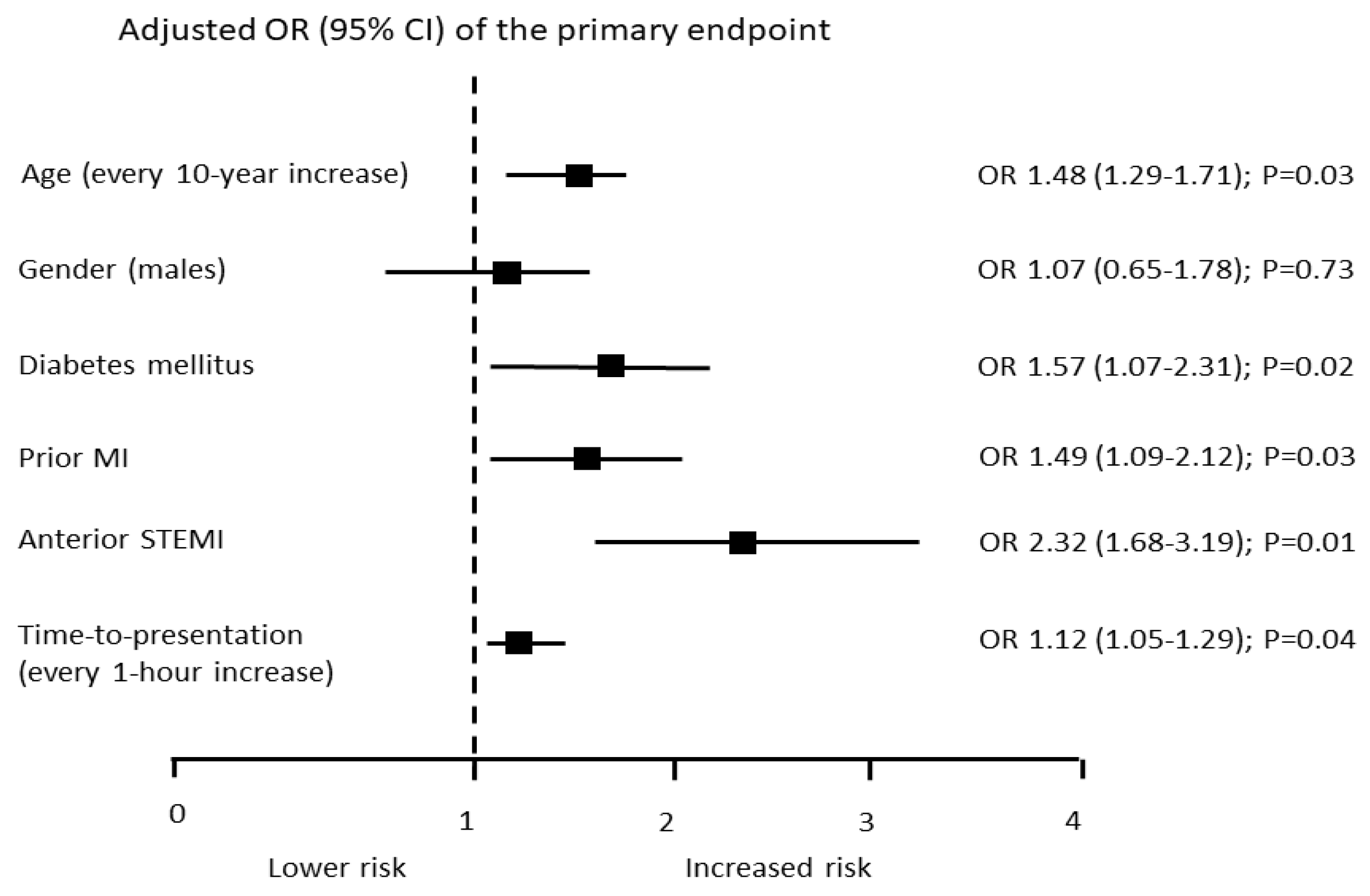

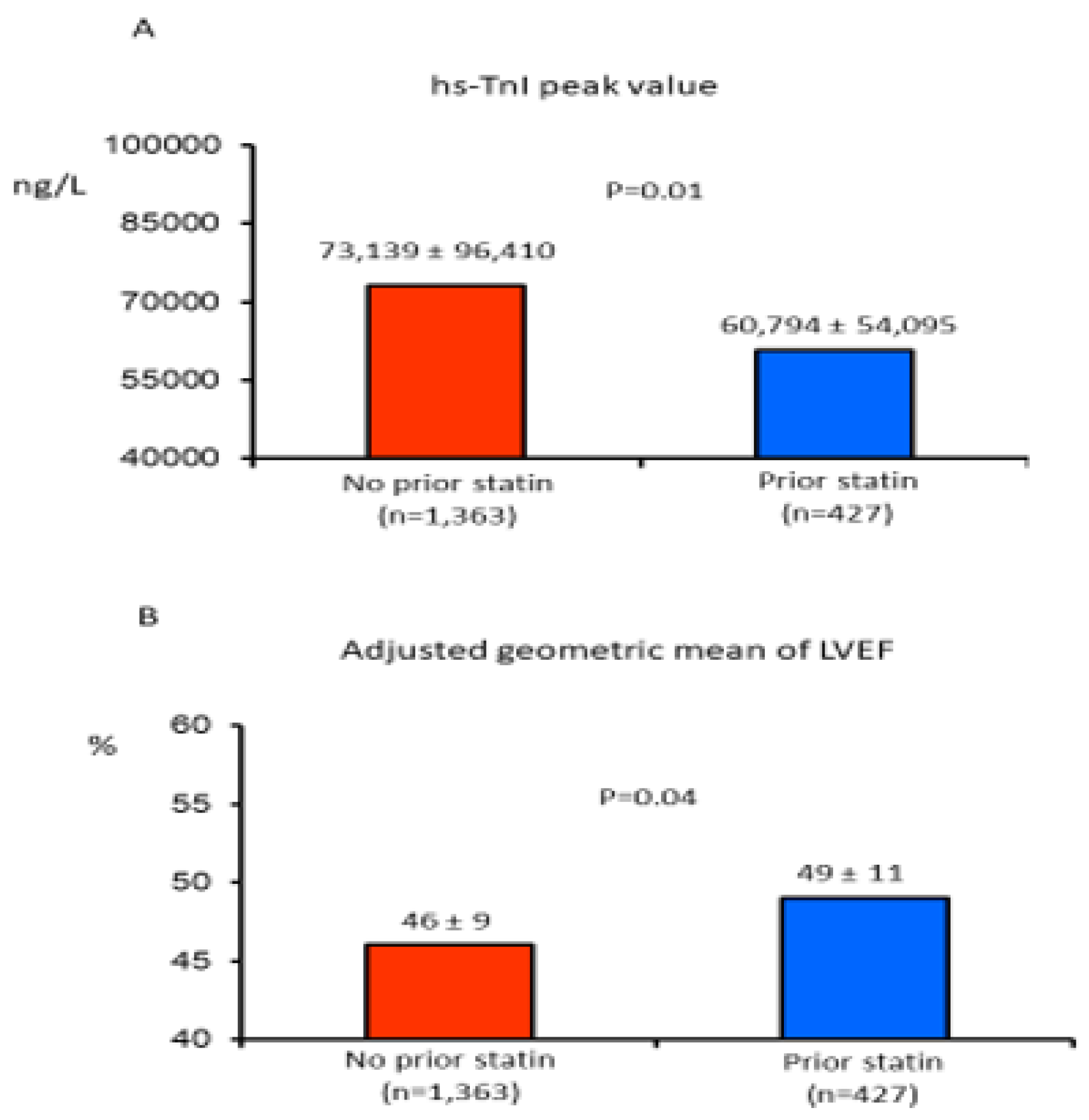

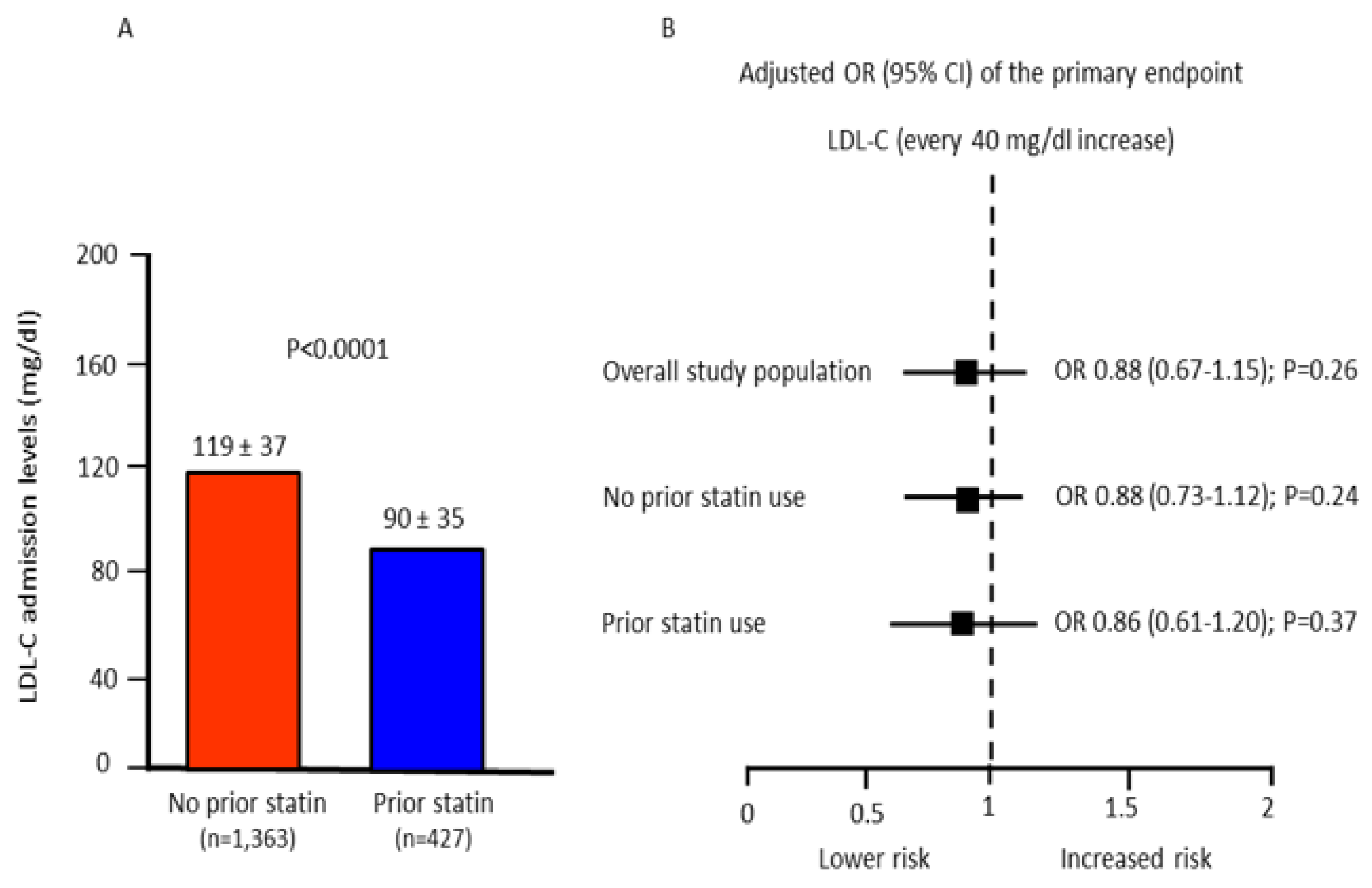

3. Results

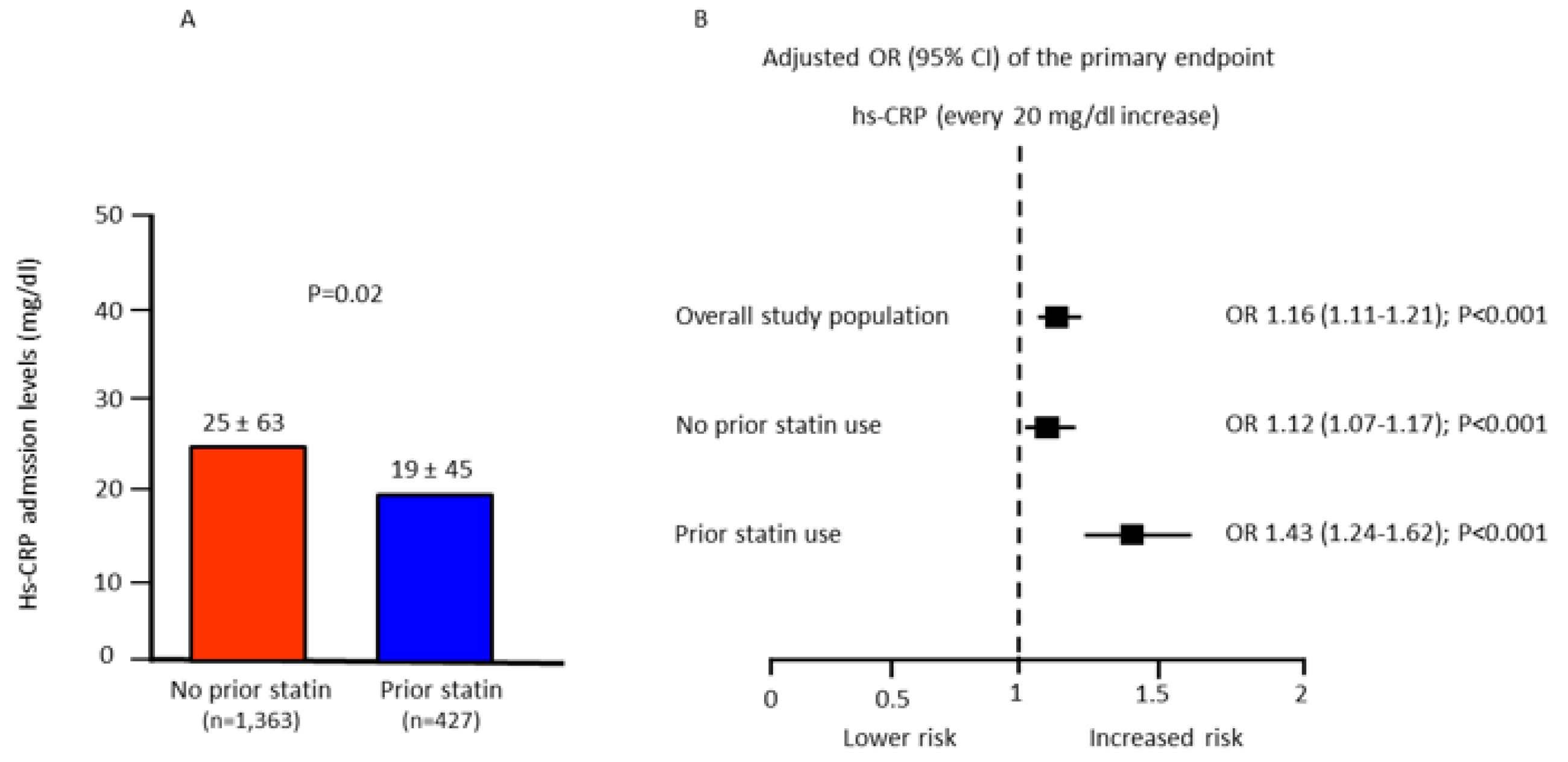

Subsection

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar]

- O’Gara, P.T.; Kushner, F.G.; Ascheim, D.D.; Casey, D.E.; Chung, M.K.; de Lemos, J.A.; Ettinger, S.M.; Fang, J.C.; Fesmire, F.M.; Franklin, B.A.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013, 127, 362–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, N.J.; Robinson, J.G.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Blum, C.B.; Eckel, R.H.; Goldberg, A.C.; Gordon, D.; Levy, D.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2889–2934. [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra, F.; Hoorntje, J.C.; de Boer, M.-J.; Reiffers, S.; Miedema, K.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Hof, A.W.V.; Suryapranata, H. Long-term benefit of primary angioplasty as compared with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1413–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, E.C.; Boura, J.A.; Grines, C.L. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: A quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003, 361, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, E.C.; Hillis, L.D. Primary PCI for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasceri, V.; Patti, G.; Nusca, A. Randomized trial of atorvastatin for reduction of myocardial damage during coronary intervention: Results from the ARMYDA (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) study. Circulation 2004, 110, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessen, B.E.; Guedeney, P.; Gibson, C.M.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Cao, D.; Lepor, N.; Mehran, R. Lipid Management in Patients Presenting With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e018897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, K.; Megalou, A.; Bazoukis, G.; Tse, G.; Manolis, A. Pre-loading therapy with statins in patients with angina and acute coronary syndromes undergoing PCI. J. Interv. Cardiol. 2017, 30, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, G.; Pasceri, V.; Colonna, G.; Miglionico, M.; Fischetti, D.; Sardella, G.; Montinaro, A.; Di Sciascio, G. Atorvastatin pretreatment improves outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing early percutaneous coronary intervention: Results of the ARMYDA-ACS randomized trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, E.O.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Picard, M.H.; Nasseri, B.A.; MacGillivray, C.; Gannon, J.; Lian, Q.; Bloch, K.D.; Lee, R.T. Rosuvastatin reduces experimental left ventricular infarct size after ischemia-reperfusion injury but not total coronary occlusion. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H1802–H1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atar, S.; Ye, Y.; Lin, Y.; Freeberg, S.Y.; Nishi, S.P.; Rosanio, S.; Huang, M.H.; Uretsky, B.F.; Perez-Polo, J.R.; Birnbaum, Y. Atorvastatin-induced cardioprotection is mediated by increasing inducible nitric oxide synthase and consequent S-nitrosylation of cycloxygenase-2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H1960–H1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H. Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.; Choi, D.; Lee, C.J.; Lee, S.H.; Ko, Y.; Hong, M.; Kim, B.; Oh, S.J.; Jeon, D.W.; et al. Efficacy of high-dose atorvastatin loading before primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: The STATIN STEMI trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 3, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.G.; Won, H.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, B.K.; Choi, D.; Hong, M.K.; Bae, J.H.; Lee, S.; Lim, D.S.; et al. Efficacy of early intensive rosuvastatin therapy in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (ROSEMARY Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellosta, S.; Paoletti, R.; Corsini, A. Safety of statins: Focus on clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Circulation 2004, 109, III50–III57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.W.; Selker, H.P.; Thiele, H.; Patel, M.R.; Udelson, J.E.; Ohman, E.M.; Maehara, A.; Eitel, I.; Granger, C.B.; Jenkins, P.L.; et al. Relationship between infarct size and outcomes following primary PCI: Patient-level analysis from 10 randomized trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenzi, G.; Cosentino, N.; Cortinovis, S.; Milazzo, V.; Rubino, M.; Cabiati, A.; De Metrio, M.; Moltrasio, M.; Lauri, G.; Campodonico, J.; et al. Myocardial Infarct Size in Patients on Long-Term Statin Therapy Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015, 116, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Olsson, A.G.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Ganz, P.; Oliver, M.F.; Waters, D.; Zeiher, A.; Chaitman, B.R.; Leslie, S.; Stern, T.; et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: The MIRACL study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001, 285, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinlay, S.; Schwartz, G.G.; Olsson, A.G.; Rifai, N.; Leslie, S.J.; Sasiela, W.J.; Szarek, M.; Libby, P.; Ganz, P. High-dose atorvastatin enhances the decline in inflammatory markers in patients with acute coronary syndromes in the MIRACL study. Circulation 2003, 108, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, D.; Wen, X.; Xie, L.; Bavry, A.A. Evidence of pre-procedural statin therapy a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuernau, G.; Eitel, I.; Wöhrle, J.; Kerber, S.; Lauer, B.; Pauschinger, M.; Schwab, J.; Birkemeyer, R.; Pfeiffer, S.; Mende, M.; et al. Impact of long-term statin pretreatment on myocardial damage in ST elevation myocardial infarction (from the AIDA STEMI CMR Substudy). Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, S.; Post, M.C.; Branden, B.J.V.D.; Eefting, F.D.; Goumans, M.-J.; Stella, P.R.; Van Es, H.W.; Wildbergh, T.X.; Rensing, B.J.; Doevendans, P.A. Early statin treatment prior to primary PCI for acute myocardial infarction: REPERATOR, a randomized placebo-controlled pilot trial. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 80, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Yun, K.H.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, Y.C.; Joe, D.-Y.; Ko, J.S.; Rhee, S.J.; Lee, E.M.; Yoo, N.J.; Kim, N.-H.; et al. Effect of high dose rosuvastatin loading before primary percutaneous coronary intervention on infarct size in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Korean Circ. J. 2014, 44, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, S.; Tsutsui, M.; Shimokawa, H.; Yamashita, T.; Tanimoto, A.; Tasaki, H.; Ozumi, K.; Sabanai, K.; Morishita, T.; Suda, O.; et al. Statin Treatment Upregulates Vascular Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase Through Akt/NF-B Pathway. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Cannon, C.P. The potential relevance of the multiple lipid-independent (pleiotropic) effects of statins in the management of acute coronary syndromes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-D.; Yang, Y.-J.; Geng, Y.-J.; Cheng, Y.-T.; Zhang, H.-T.; Zhao, J.-L.; Yuan, J.-Q.; Gao, R.-L. The cardioprotection of simvastatin in reperfused swine hearts relates to the inhibition of myocardial edema by modulating aquaporins via the PKA pathway. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 2657–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwanger, O.; Santucci, E.V.; de Barros, E.S.; Jesuíno, I.A.; Damiani, L.P.; Barbosa, L.M.; Santos, R.H.N.; Laranjeira, L.N.; Egydio, F.M.; Borges de Oliveira, J.A.; et al. Effect of Loading Dose of Atorvastatin Prior to Planned Percutaneous Coronary Intervention on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Acute Coronary Syndrome: The SECURE-PCI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Haager, P.; Suliman, H.; Christott, P.; Radke, P.; Blindt, R.; Kelm, M. Effect of statin therapy before Q-wave myocardial infarction o myocardial perfusion. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 101, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, K.; Ito, H.; Kawano, S.; Okamura, A.; Kurotobi, T.; Date, M.; Inoue, K.; Fujii, K. Chronic pre-treatment of statins is associated with the reduction of the no-reflow phenomenon in the patients with reperfuse acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.A.; Danielson, E.; Rifai, N.; Ridker, P.M. Effect of statin therapy on C-reactive protein levels: The pravastatin inflammation/CRP evaluation (PRINCE): A randomized trial and cohort study. JAMA 2001, 286, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidmann, L.; Obeid, S.; Mach, F.; Shahin, M.; Yousif, N.; Denegri, A.; Muller, O.; Räber, L.; Matter, C.M.; Lüscher, T.F. Pre-existing treatment with aspirin or statins influences clinical presentation, infarct size and inflammation in patients with de novo acute coronary syndromes. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 275, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, B.W.; Hong, T.J.; Choe, J.C.; Lee, H.W.; Oh, J.H.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, H.C.; Cha, K.S.; Jeong, M.H. Lower In-Hospital Ventricular Tachyarrhythmia in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Receiving Prior Statin Therapy. Angiology 2018, 69, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Prior Statin Therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 427) | No (n = 1363) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 68 ± 11 | 65 ± 12 | <0.0001 |

| Men, n (%) | 344 (81%) | 1010 (74%) | 0.007 |

| Body weight (kg) | 76 ± 14 | 76 ± 15 | 0.65 |

| Height (cm) | 169 ± 10 | 169 ± 9 | 0.55 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 127 (30%) | 210 (15%) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 306 (72%) | 723 (53%) | <0.0001 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 146 (34%) | 584 (43%) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n, (%) | 201 (47%) | 89 (7%) | <0.0001 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass, n (%) | 72 (17%) | 35 (3%) | <0.0001 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 186 (52%) | 70 (6%) | <0.0001 |

| Time-to-treatment (h) | 5 ± 7 | 6 ± 5 | 0.72 |

| Anterior AMI, n (%) | 167 (39%) | 612 (45%) | 0.03 |

| LVEF (%) | 48 ± 11 | 48 ± 12 | 0.86 |

| Medication before hospital admission, n (%) | |||

| Aspirin | 159 (37%) | 244 (17%) | <0.0001 |

| Beta-blockers | 184 (51%) | 192 (17%) | 0.01 |

| ACE/AR blockers | 187 (52%) | 291 (26%) | <0.0001 |

| Warfarin | 19 (5%) | 47 (4%) | 0.38 |

| Medication during CCU stay, n (%) | |||

| DAPT | 427 (100%) | 1363 (100%) | 1 |

| Statin | 427 (100%) | 1363 (96%) | 1 |

| Beta-blockers | 290 (82%) | 902 (82%) | 0.98 |

| ACEi/ARB | 244 (69%) | 725 (66%) | 0.24 |

| Laboratory values at hospital admission | |||

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 160 ± 61 | 157 ± 64 | 0.46 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1 ± 0.43 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 0.002 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 74 ± 25 | 78 ± 24 | 0.02 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.7 ± 1.8 | 14.0 ± 1.9 | 0.004 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 156 ± 40 | 185 ±43 | <0.0001 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 48± 13 | 43 ± 13 | 0.2 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 114 ±62 | 120 ± 71 | 0.3 |

| Prior Statin Therapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 427) | No (n = 1363) | p Value | |

| Mortality, n (%) | 10 (2.3%) | 50 (3.7%) | 0.18 |

| CPR, VT, or VF, n (%) | 52 (12%) | 188 (14%) | 0.39 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 62 (14%) | 185 (14%) | 0.84 |

| High-degree AV conduction disturbances, n (%) | 25 (6%) | 56 (5%) | 0.16 |

| Acute pulmonary edema, n (%) | 48 (11%) | 158 (12%) | 0.84 |

| Respiratory failure requiring MV, n (%) | 15 (4.2%) | 72 (6.4%) | 0.11 |

| Cardiogenic shock requiring IABP, n (%) | 30 (7%) | 129 (9.5%) | 0.12 |

| Major bleeding requiring blood transfusion, n (%) | 13 (3%) | 31 (2%) | 0.37 |

| CCU length of stay (days) | 4 ± 2 | 4 ± 3 | 0.89 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lanza, O.; Cosentino, N.; Lucci, C.; Resta, M.; Rubino, M.; Milazzo, V.; De Metrio, M.; Trombara, F.; Campodonico, J.; Werba, J.P.; et al. Impact of Prior Statin Therapy on In-Hospital Outcome of STEMI Patients Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11185298

Lanza O, Cosentino N, Lucci C, Resta M, Rubino M, Milazzo V, De Metrio M, Trombara F, Campodonico J, Werba JP, et al. Impact of Prior Statin Therapy on In-Hospital Outcome of STEMI Patients Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(18):5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11185298

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanza, Oreste, Nicola Cosentino, Claudia Lucci, Marta Resta, Mara Rubino, Valentina Milazzo, Monica De Metrio, Filippo Trombara, Jeness Campodonico, José Pablo Werba, and et al. 2022. "Impact of Prior Statin Therapy on In-Hospital Outcome of STEMI Patients Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 18: 5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11185298

APA StyleLanza, O., Cosentino, N., Lucci, C., Resta, M., Rubino, M., Milazzo, V., De Metrio, M., Trombara, F., Campodonico, J., Werba, J. P., Bonomi, A., & Marenzi, G. (2022). Impact of Prior Statin Therapy on In-Hospital Outcome of STEMI Patients Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(18), 5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11185298