Abstract

Sepsis is associated with 11 million global deaths annually. Although serious consequences of sepsis can generally be avoided with prevention and early detection, research has not yet addressed the efficacy of evidence-based health information formats for different risk groups. This study examines whether two evidence-based health information formats—text based and graphical—differ in how well they foster informed choice and risk and health literacy and in how well they support different sepsis risk groups. Based on a systematic literature review, two one-page educative formats on sepsis prevention and early detection were designed—one text based and one graphical. A sample of 500 German participants was randomly shown one of the two formats; they were then assessed on whether they made informed choices and on their risk and health literacy. For both formats, >70% of participants made informed choices for sepsis prevention and >75% for early detection. Compared with the graphical format, the text-based format was associated with higher degrees of informed choice (p = 0.012, OR = 1.818) and risk and health literacy (p = 0.032, OR = 1.710). Both formats can foster informed choices and risk and health literacy on sepsis prevention and early detection, but the text-based format appears to be more effective.

1. Introduction

Every year, 11 million people worldwide die from sepsis, which is the primary cause of death from infection [1,2]. In Europe, incident sepsis cases in 2017 amounted to 2,430,000, with 545,000 deaths resulting; in Germany alone in 2016, there were 280,000 sepsis cases, leading to 55,000 deaths [1,3]. Survivors often face long-term functional, cognitive, or physical disabilities [4]. These numbers are particularly depressing given that many sepsis-associated deaths could be prevented with measures such as vaccinations, e.g., against influenza or pneumococcal infection, good wound hygiene, and timely detection and treatment [5,6,7,8,9]. Effectively addressing the threat of sepsis requires people to have a basic knowledge of potential causes and symptoms, as well as the benefits and harms of preventive measures, in order to make informed choices about potential courses of action [10]. However, studies on sepsis-associated awareness and knowledge in various countries have demonstrated considerable knowledge gaps [11,12,13]. For example, an international survey on public perceptions of and attitudes toward sepsis showed that 88% of participants from Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, France, and the United States had never heard of sepsis [13]. In a German survey, 89% of participants over 60 reported that they had heard of sepsis, but they tended to underestimate the incidence and mortality rates of sepsis, and only 17% were aware that vaccination can help prevent sepsis [14].

One reason for the lack of awareness around sepsis might be that the available information on sepsis is not understood, in part due to incomplete or intransparent information formats. Many people, including patients who have to make decisions about their health, encounter difficulties in understanding medical information and risks [15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, certain presentation formats can help people understand numerical information [16,18,21,22,23]. For example, statistical formats such as absolute risk information have been shown to foster the comprehension of medical benefits and harms. In contrast, relative risk information misleads doctors and laypeople alike [16,24,25,26,27]. This is because relative numbers—in contrast to absolute numbers—hide the denominator they relate to, thereby providing incomplete and misleading risk information [16,28,29]. Furthermore, presenting health information in transparent graphical formats rather than in text-based formats can help people understand risks and make informed decisions [30]. For instance, graphical representations can increase the probability of preventive health behaviour and foster the recall of health information [30,31,32,33,34,35].

Nonetheless, studies show that when it comes to presentation formats, one size may not fit all: Different target groups (defined, e.g., by age, numeracy, or graph literacy) may require different forms of presentation to best improve their informed choices [19,34,36,37]. For instance, older patients tend to face more health risks and need to make more medical decisions; it is therefore necessary to tailor information formats to their specific needs.

The aim of the present study is to determine whether two evidence-based health information formats—text based and graphical—differ in how well they foster informed choice (primary endpoint), how well they foster risk and health literacy on sepsis (secondary endpoint), and how well they support different sepsis risk groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Overview

We employed an online randomized-controlled (text-based vs. graphical) trial (RCT). Participants were randomly assigned to either a text-based or a graphical health format at a 1:1 ratio. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study but were blind to the condition they were assigned to. This RCT is part of the SepsisWissen project funded by the Innovationfonds of the German Federal Joint Committee (01VSF19020). We registered the trial (Risk communication on sepsis early detection and prevention; RICOSEP) at the German Clinical Trial Register (DRKS00024850) and adhered to the CONSORT checklist. The original registration was amended in two ways after a soft launch with 30 recruited participants. While initially a pre–post design was planned, we had to decide against that after screening the data from the soft launch. Assessing the outcome measures prior to the intervention with the prequestionnaire directed participants’ attention towards the aspects addressed in the prequestionnaire. Thus, as they read through the risk information, a strong attentional bias was created which would not exist in a real-world setting and might have created a ceiling effect of measured endpoints regardless of format, which would have limited the validity of the trial. Furthermore, an additional item was included in the study that queried which 3 of 15 pieces of information about sepsis participants thought were the most important to know.

Recruitment was restarted for the adapted study design. The data from the 30 soft-launch participants were not included in the main analyses. However, some highlights which might provide exploratory insights are outlined in this paper and in the Supplementary Materials (Table S3).

2.2. Procedure

Participants gave informed consent prior to the study. Participants were screened according to preset criteria for age, pre-existing conditions (see Supplementary Materials, Table S1), and education. Either the text-based or the graphical health format was shown. Participants could spend as much time as they wanted to read the educative material, but based on pre-testing, a time minimum was set for 2.5 min, after which participants could proceed to the main survey.

2.3. Sample Size

In order for one information format to be considered superior, we required the conservative difference in informed choice to be at least 15 percentage points. The rationale for this benchmark was based on effects from survey studies comparing currently available standard information to either of the risk formats we used in our trial [38,39,40]. Taking these postulated differences into account (52% vs. 37% informed choice), planning for a chi-square test and aiming for a power of 90% at an α level of 5% (two-tailed), we needed 242 participants for each intervention arm (nQuery 7.0).

2.4. Participant Characteristics

Altogether, 500 people at higher risk for sepsis—that is, aged ≥ 60 years and/or presenting with pre-existing conditions such as cancer or chronic diseases—participated. Recruitment was undertaken by the market research institute IPSOS Health (Nuremberg, Germany). IPSOS used an established online panel to recruit 150 participants aged 60 years and older without known pre-existing conditions in Germany. A further 350 patients with pre-existing conditions (see Supplementary Materials, Table S2) were recruited by contacting physicians and support groups. Participation was monetarily reimbursed.

2.5. Participant Flow

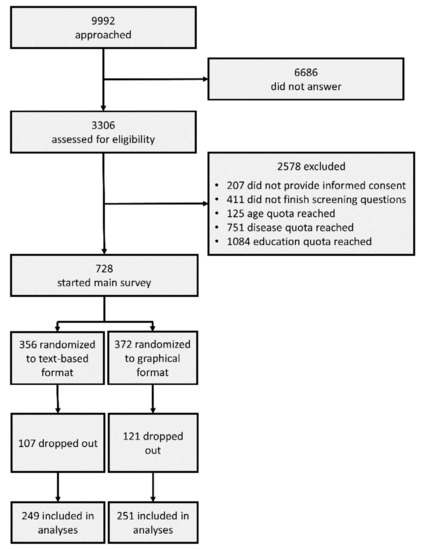

IPSOS approached 9992 individuals, of whom 3306 started the trial upon invitation. Of these, 207 did not provide informed consent, 411 abandoned the survey prematurely, and 1960 were rejected because targeted quotas were already filled, leaving 728 participants to start the main survey. Of these, 228 dropped out (text-based: 107; graphical: 121); a final total of 500 participants (text-based: 249, graphical: 251) finished the survey (see Figure 1). Information on gender, age, and education were available for 332 of all participants who dropped out.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow.

2.6. Materials

Information Formats

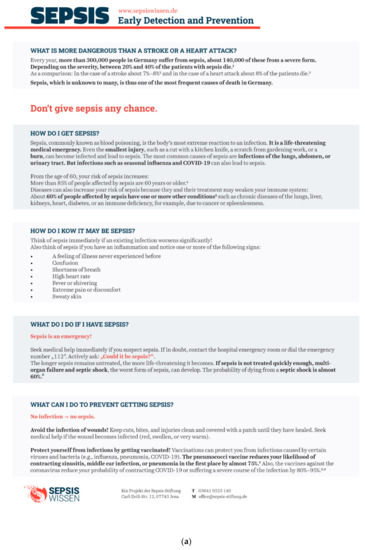

Based on the guideline for evidence-based health information, the content of the evidence-based formats on prevention and early detection of sepsis was informed by a systematic literature review [41]. Along with general information about the prevalence and mortality of sepsis in Germany (compared with other conditions), the information formats covered three aspects of prevention (wound hygiene, chronic preconditions, and vaccinations) and two aspects of early detection (symptoms and sepsis as an emergency). Comprehensibility was piloted with 10 members of the general public, and the content was revised after feedback. A text-based format and a graphical format of the information were then developed in cooperation with the branding and communications agency Bloominds (Berlin, Germany). The content of the two formats differed only in that the graphical format featured images such as icons and graphs rather than only text. Figure 2 shows the two information formats.

Figure 2.

(a) English translations of the text-based and (b) graphical information formats on prevention and early detection of sepsis.

2.7. Measures

2.7.1. Informed Choice

The primary endpoint was the validated binary, combined measure of informed choice according to Marteau et al., which differentiates between informed and noninformed choice [10,40]. We separately assessed the prevention and early detection of sepsis. As Marteau’s measure was originally validated on a prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome, it had to be reframed specifically to sepsis for our study (see Supplementary Materials, Figure S1). Three aspects are captured by this measure: risk and health literacy, attitude, and decision.

Risk and health literacy was measured with eight items. For instance, to capture how well participants understood the numerical information provided, they were asked questions such as “How many people do you think get sepsis in Germany every year?” Responses for the item that asked for a count were counted as correct if they were within ±5% of the correct value (i.e., if the right answer was 300,000, responses ranging from 285,000 to 315,000 were counted as correct). Two questions asked for a percentage; answers within ±5 percentage points were counted as correct (e.g., where the right answer was 75%, responses ranging from 70% to 80% were counted as correct). Other questions in this section were aligned to the method used in the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU [42]), which instead of capturing direct knowledge captures people’s impressions of how well they understand, evaluate, and apply health information. Items were adjusted for sepsis and assessed along a four-point Likert scale (e.g., “On a scale from very easy to very difficult, how easy do you find it to remember the most important protective measures against sepsis?”). Health literacy items were counted as adequate if they were rated as very easy or easy. To calculate a participant’s risk and health literacy score, we tallied all their “correct” and “adequate” responses; if they had five or more, they were considered to have sufficient risk and health literacy.

Attitudes toward prevention (“With respect to protection from sepsis, I find vaccinations to be…”) and early detection (“In case of signs for sepsis, being asked to actively draw the attention of physicians to the possibility of sepsis is something that I find to be...”) were assessed with four items, each rated on a four-point Likert scale [38]: reassuring (1)–worrying (4), important (1)–unimportant (4), a good thing (1)–a bad thing (4), an advantage (1)–a disadvantage (4). Attitude was regarded as positive if the mean score across all four options was <2.5.

Decision was assessed with one yes/no question for prevention (“To avoid sepsis, I will have my vaccination status checked promptly and, if necessary, have my vaccinations refreshed”) and another one for early detection (“If I observe any signs of sepsis or a rapid deterioration in my general condition in the future, I will seek medical attention immediately and actively approach the staff about sepsis”).

Informed choice was then combined from the three aspects: A participant’s choice was classified as informed if their risk and health literacy was categorized as adequate and their attitude (positive or negative) corresponded with their final decision. Participants who did not display adequate knowledge or whose attitudes and decision did not match (e.g., who demonstrated a positive attitude toward prevention but decided against it) were classified as making uninformed choices regarding prevention or early detection of sepsis. As a secondary endpoint, we analysed risk and health literacy as its own entity. All endpoints were assessed after participants had seen one or the other information format.

2.7.2. Relevance of Information

To further inform SepsisWissen’s planned sepsis awareness campaign, an additional item asked participants what information about sepsis they consider to be most relevant. Participants could choose 3 pieces of information from a list of 15, including “information about how dangerous sepsis is compared to other diseases” and “the information that a significantly deteriorating infection can indicate sepsis.”

2.8. Statistical Methods

Frequencies tested via odds ratios (OR) and chi-square tests were used to analyse differences between the two formats in the primary endpoint of informed choice as well as in sepsis-specific risk and health literacy. In planned subgroup analyses, these differences were also tested within age groups (<60 vs. ≥60 years). Differences between age groups were analysed with chi-square tests. The online questionnaire did not permit item nonresponse; there were therefore no missing values. Data were stored and analysed with IBM SPSS Statistics 26.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 reports the distribution of gender, age, and education for participants in the two intervention arms. The distributions of participants exposed to the text-based and graphical formats were similar in terms of gender and age but different in terms of education: There were more participants with higher education in the graphical format group (see Table 1). Details on the diseases of the 350 participants with known pre-existing conditions—including 235 under 60 years of age—are shown in Table 2. All participants without known pre-existing conditions (n = 150) were required to be aged 60 or older.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (n = 500) in Both Intervention Arms.

Table 2.

Pre-existing Conditions of Participants (n = 350) in Both Intervention Arms.

3.2. Informed Choice and Risk and Health Literacy for Text-Based and Graphical Formats

Overall, 75% of participants made an informed choice about sepsis prevention after the intervention, and 82% demonstrated adequate risk and health literacy on sepsis prevention. For the early detection of sepsis, 81% made an informed choice after intervention, and 83% exhibited adequate risk and health literacy (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Overall Frequencies for Informed Choice and Risk and Health Literacy for Prevention and Early Detection of Sepsis.

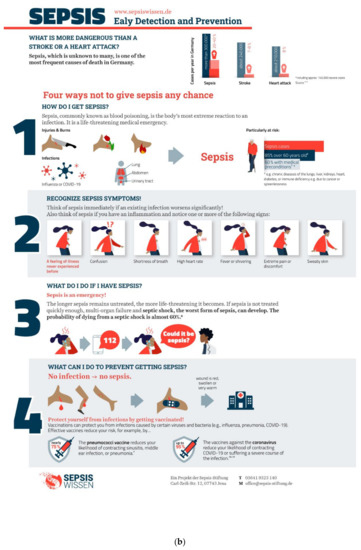

The text-based format was associated with higher rates of informed choice (86%) and adequate risk and health literacy (87%) on early detection of sepsis than was the graphical format (informed choice 76%, p = 0.012, OR = 1.818; risk and health literacy 79%, p = 0.032, OR = 1.710). No such differences between formats were found for sepsis prevention (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentages and statistical significance according to chi-square tests for informed choice and risk and health literacy for text-based and graphical formats. Note: Text-based n = 249; graphical n = 251. * p ≤ 0.05.

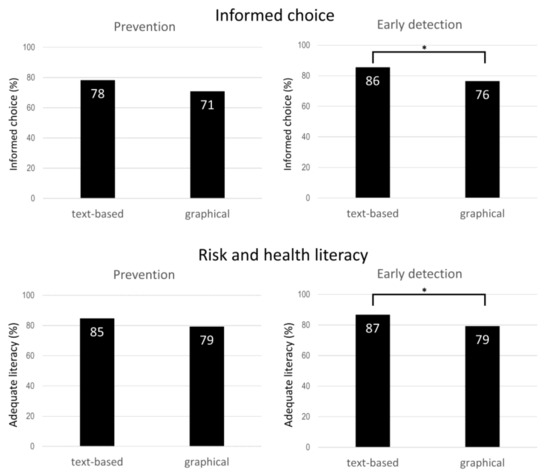

3.3. Differences between Age Groups

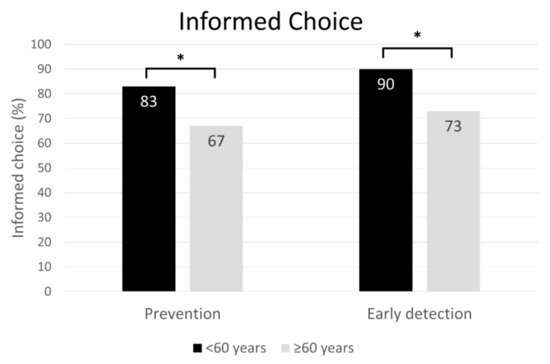

Of the participants under 60 years old, 83% (prevention) and 90% (early detection) made an informed choice; of participants aged 60 years or older, only 67% (prevention) and 73% (early detection) made an informed choice (see Figure 4; prevention: p < 0.001, early detection: p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Informed choices and statistical significance according to chi-square test by age group. Note: Under 60 years: n = 235; 60 years and older: n = 265. * p < 0.001.

Furthermore, for participants under 60 years old (n = 235), the text-based format was associated with more informed choices than was the graphical format for both sepsis prevention (p = 0.005, OR = 2.878) and early detection (p = 0.027, OR = 1.833). These differences were not found for participants aged 60 years and older (n = 265). We did not detect any age-related differences between the two formats in terms of risk and health literacy (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequencies and statistical significance in chi-square test for informed choice and risk and health literacy by age group.

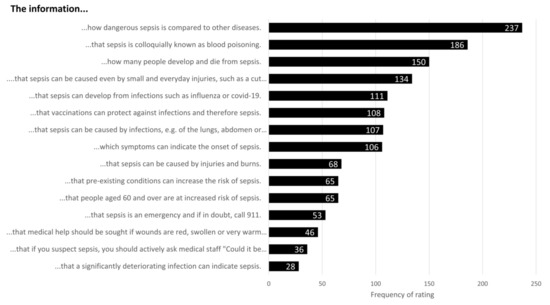

3.4. Relevance of Information

Of 15 pieces of information about sepsis on the list, participants considered 3 to be most relevant. Information about the danger of sepsis in relation to other diseases (e.g., cancer) was rated as relevant most often (237 times), followed by the information that sepsis is colloquially called “blood poisoning” (186 times) and information on the annual incidence and death rate of sepsis (150 times; see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Relevance ratings for sepsis information.

3.5. Soft-Launch Data: Pre–Post Differences

Before viewing the information formats, fewer than half of the 30 participants in the soft launch of the study made an informed choice on the early detection (40%) and prevention of sepsis (27%). After seeing the information formats, 63% of participants made an informed choice on early detection and 70% made an informed choice on the prevention of sepsis (see Supplementary Materials, Table S3).

4. Discussion

For the prevention and early detection of sepsis, more than 74% of participants made an informed choice after reading either of the health information formats. We found that evidence-based health information in a text-based format was more effective at fostering informed choices and risk and health literacy than a graphical format with regard to the early detection of sepsis; no difference between formats was found for informed choice and risk and health literacy with regard to sepsis prevention. For participants under 60 years old, the text-based format was more effective at fostering informed choices on both the early detection and the prevention of sepsis. These results indicate that low-threshold, easy-to-implement health information has the potential to improve sepsis awareness, particularly in specific risk groups.

Our finding that the text-based format outperformed the graphical format is not completely in line with the findings of Garcia-Retamero and Cokely [36]. In their systematic review of studies on the efficacy of visual aids, they found that 88% of the studies demonstrated visualisations to be more effective than text in promoting risk literacy. However, Garcia-Retamero and Cokely also stressed the importance of numeracy and graph literacy for understanding of visualisations [36]. Because numeracy and graph literacy were not assessed in our study, their effects on our results remains unclear; perhaps a subgroup of participants with at least moderate graph literacy might have profited more from the graphical format than from the text-based format.

Another reason the text-based format performed better in our study might be that the graphical format presented different kinds of visualisations (e.g., bar charts, icons) and contained not only numerical information but also verbal qualitative information. The mix of different components and types of information, as well as the visualisations of complex information (e.g., the course of action for the early detection of sepsis), may have made it harder for participants to grasp the exact meaning of the information in the graphical format than in the text-based format [36]. Although graphical information has been found to be easier to remember, we can only speculate on whether the graphical format would have been better at supporting informed choices in the long run since endpoints were assessed directly after the presentation of the information formats [34,43,44,45]. Future studies with follow-up assessments might shed light on this point.

In the present study, 83% (prevention) and 90% (early detection) of the participants under 60 years old made an informed choice, but only 67% (prevention) and 73% (early detection) of the participants aged 60 years or older did so. Participants younger than 60 years old benefited more from the text-based format than from the graphical format in terms of making an informed choice; this was not the case for participants aged 60 years and older, for whom there was no difference between formats. Although participants under 60 years old differed from participants aged 60 years and older in education, with fewer older participants having received higher education (see Supplementary Materials, Table S4), the results may nevertheless suggest the importance of offering tailored health information formats to address different informational needs. Future studies might for example examine whether individuals aged 60 years and older profit more from other formats, such as experience-based approaches. Information formats such as the single page used in our study could be adapted for print with text-based information on one side and graphical information on the other, thereby addressing the needs of as many people as possible on one sheet of paper.

Another way to increase the relevance—and therefore potentially the effect—of evidence-based health information might be to focus on the information that is especially relevant to the target group. We found that participants tended to regard relatively basic information such as the prevalence and mortality of sepsis, its potential causes, and the fact that sepsis is also known as blood poisoning as most relevant. It might be helpful to centre evidence-based health information on these topics as an engaging starting point.

Our study has limitations that warrant attention. First, since we needed to omit the baseline measure to avoid attentional biases, no pre–post design was employed. Therefore, the present study could only assess the outcomes of evidence-based health information formats after the intervention, and no comparison with the initial state could be made. However, the data from the soft launch, which featured a pre–post design, indicate that both informed choice and risk and health literacy might have been lower before the intervention. This notion is supported by the fact that previous studies have found considerable knowledge gaps regarding sepsis [11,12,13,14]. Future studies should further investigate the effects of evidence-based health information on informed choice and risk and health literacy, for example by implementing a pre–post design with a follow-up assessment. Second, our results are based on a sample with an increased risk of sepsis. Therefore, the results may not generalize to the general population. People with pre-existing conditions or senior citizens might be more sensitive to health-related topics such as sepsis. Moreover, the nonresponse rate was high. We do not know how nonrespondents differed from participants. It is conceivable that participants with stronger interest in the topic had both higher interest in reading the information and higher motivation to complete the entire questionnaire, and that the sample may thus have been selective in that regard. It is also conceivable that participants dropped out because they found the information formats uninformative; in both cases, we might expect that informed choice would have been somewhat lower in participants who dropped out. Nonetheless, comparing participants with people who left the survey prematurely shows that although the former included more men, age and education did not differ, thus indicating that the study sample was not selective in this regard. Third, the components of risk and health literacy were assessed in different ways. While risk literacy was examined using questions in an open numerical or multiple-choice format, health literacy was measured with three items adapted from the HLS-EU, using a Likert scale ranging from “very easy” to “very difficult”. The HLS-EU has been criticized for assessing subjective health literacy rather than health-related knowledge itself [46]. Additionally, some items in the HLS-EU might be answered as “very difficult” even by health professionals and informed individuals since the task itself (e.g., understanding a package leaflet) is very difficult. We chose and adapted the items assessing sepsis specific health literacy carefully to avoid this problem. Third, our study assessed decision as an intention and did not examine whether this intention translated into actual behaviour. Future studies could employ a follow-up measurement to make it possible to assess prevention behaviour (e.g., asking whether participants had had their vaccination status checked), but this might be difficult for early detection because the number of sepsis cases would presumably be low.

5. Conclusions

These limitations notwithstanding, our RCT is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to examine the differences in a text-based and a graphical evidence-based health information format on sepsis regarding informed choice and risk and health literacy. The text-based format was better than the graphical format at fostering informed choice and risk and health literacy for the early detection of sepsis, and younger participants (under 60 years old) seemed to profit more from the text-based than the graphical format in terms of making informed choices, although this was not the case for older respondents (aged 60 years and older). Furthermore, participants regarded information about the prevalence and mortality rates of sepsis, its potential causes, and its colloquial name, “blood poisoning,” as the most relevant information on sepsis. Our findings can form the basis for studies examining the effectiveness of different health information formats for various risk groups and can be used to inform sepsis awareness campaigns on how best to offer evidence-based health information to high-risk target groups.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm11133659/s1, Table S1: Pre-set criteria for the recruitment of participants with and without pre-existing conditions and actual frequencies in the sample; Table S2: Demographic characteristics of participants with and without pre-existing conditions; Figure S1: English translation of the survey items on informed choice; Table S3: Frequencies and percentages for informed choice and for adequate risk-and-health literacy for the prevention and early detection of sepsis for the 30 participants of the soft-launch with a pre-post design; Table S4: Demographic characteristics of participants under and those ages 60 years and older.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: O.W.; Methodology, O.W., K.R., C.F.-S. and D.S.; Formal Analysis: O.W., L.J.D. and A.P.; Investigation: O.W. and L.J.D.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: L.J.D., O.W. and A.P.; Writing—Review & Editing: O.W., K.R., S.B., D.S., C.F.-S. and A.P.; Visualization: L.J.D. and O.W.; Supervision: O.W. and K.R.; Project Administration: L.J.D. and O.W.; Funding Acquisition: O.W., K.R., C.F.-S. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Innovation Funds of the German Federal Joint Committee, grant number 01VSF19020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Jena University Hospital (protocol code 2020-1921_1-Bef, 11.03.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in OSF (doi 10.17605/OSF.IO/85DHZ).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D.R.; Colombara, D.V.; Ikuta, K.S.; Kissoon, P.N.; Finfer, P.S.; et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, N.; Matthäus-Krämer, C.; Schwarzkopf, D.; Scherag, A.; Born, S.; Reinhart, K.; Fleischmann-Struzek, C. Association between sepsis incidence and regional socioeconomic deprivation and health care capacity in Germany—An ecological study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashyna, T.J.; Cooke, C.; Wunsch, H.; Kahn, J. Population Burden of Long-Term Survivorship After Severe Sepsis in Older Americans. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bloos, F.; Rüddel, H.; Thomas-Rüddel, D.; Schwarzkopf, D.; Pausch, C.; Harbarth, S.; Schreiber, T.; Gründling, M.; Marshall, J.; Simon, P.; et al. Effect of a multifaceted educational intervention for anti-infectious measures on sepsis mortality: A cluster randomized trial. Intensiv. Care Med. 2017, 43, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, I.V.R.; Phillips, G.S.; Alpern, E.R.; Angus, D.C.; Friedrich, M.E.; Kissoon, N.; Lemeshow, S.; Levy, M.M.; Parker, M.M.; Terry, K.M.; et al. Association Between the New York Sepsis Care Mandate and In-Hospital Mortality for Pediatric Sepsis. JAMA 2018, 320, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rhodes, A.; Evans, L.E.; Alhazzani, W.; Levy, M.M.; Antonelli, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, A.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 304–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, C.W.; Gesten, F.; Prescott, H.C.; Friedrich, M.E.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Phillips, G.S.; Lemeshow, S.; Osborn, T.; Terry, K.M.; Levy, M.M. Time to Treatment and Mortality during Mandated Emergency Care for Sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, V.X.; Fielding-Singh, V.; Greene, J.D.; Baker, J.M.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Bhattacharya, J.; Escobar, G.J. The timing of early antibiotics and hospital mortality in sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marteau, T.M.; Dormandy, E.; Michie, S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect. 2001, 4, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mellhammar, L.; Christensson, B.; Linder, A. Public Awareness of sepsis is low in sweden. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015, 2, ofv161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, M.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, C.; Jo, Y.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kang, K.W.; Lee, S.H.; Park, C.; Kim, J.; et al. Awareness and knowledge of sepsis in the general Korean population: Comparison with the awareness and knowledge of acute myocardial infarction and stroke. Clin. Exp. Emerg Med. 2014, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rubulotta, F.M.; Ramsay, G.; Parker, M.M.; Dellinger, R.P.; Levy, M.M.; Poeze, M. An international survey: Public awareness and perception of sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitze, S.; Fleischmann-Struzek, C.; Betsch, C.; Reinhart, K.; Vaccination60+ Study Group. Determinants of sepsis knowledge: A representative survey of the elderly population in Germany. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Retamero, R.; Galesic, M. Who proficts from visual aids: Overcoming challenges in people’s understanding of risks. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Gaissmaier, W.; Kurz-Milcke, E.; Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S. Helping doctors and patients make sense of health statistics. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2007, 8, 53–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, V.F.; Nelson, W.L.; Han, P.K.; Dieckmann, N.F. How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 943–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wegwarth, O.; Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S.; Gaissmaier, W.; Gigerenzer, G. Do physicians understand cancer screening statistics? A national survey of primary care physicians in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wegwarth, O.; Gigerenzer, G. US gynecologists’ estimates and beliefs regarding ovarian cancer screening’s effectiveness 5 years after release of the PLCO evidence. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegwarth, O.; Widschwendter, M.; Cibula, D.; Sundström, K.; Portuesi, R.; Lein, I.; Rebitschek, F.G. What do European women know about their female cancer risks and cancer screening? A cross-sectional online intervention survey in five European countries. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffrage, U.; Lindsey, S.; Hertwig, R.; Gigerenzer, G. Communicating statistical information. Science 2000, 290, 2261–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S.; Welch, H.G. The drug facts box: Providing consumers with simple tabular data on drug benefit and harm. Med. Decis. Mak. 2007, 27, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegwarth, O.; Kurzenhauser-Carstens, S.; Gigerenzer, G. Overcoming the knowledge-behavior gap: The effect of evidence-based HPV vaccination leaflets on understanding, intention, and actual vaccination decision. Vaccine 2014, 32, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Covey, J. A meta-analysis of the effects of presenting treatment benefits in different formats. Med. Decis. Mak. 2007, 27, 638–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffrage, U.; Gigerenzer, G. Using natural frequencies to improve diagnostic inferences. Acad. Med. 1998, 73, 538–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, C.D.; Chen, E.; Strauss, B. Measured enthusiasm: Does the method of reporting trial results alter perceptions of therapeutic effectiveness? Ann. Intern. Med. 1992, 117, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegwarth, O.; Wagner, G.G.; Gigerenzer, G. Can facts trump unconditional trust? Evidence-based information halves the influence of physicians’ non-evidence-based cancer screening recommendations. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0183024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Wegwarth, O.; Feufel, M. Misleading communication of risk. BMJ 2010, 341, c4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Edwards, A. Simple tools for understanding risks: From innumeracy to insight. BMJ 2003, 327, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Retamero, R.; Cokely, E.T. Communicating health risks with visual aids. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.S.; Cox, A.D.; Sturm, L.; Zimet, G. Behavioral interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptability among mothers of young girls. Health Psychol. 2010, 29, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Retamero, R.; Cokely, E.T. Effective communication of risks to young adults: Using message framing and visual aids to increase condom use and STD screening. J. Exp. Psychol Appl. 2011, 17, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vogt, F.; Marteau, T.M. Perceived effectiveness of stop smoking interventions: Impact of presenting evidence using numbers, visual displays, and different timeframes. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012, 14, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaissmaier, W.; Wegwarth, O.; Skopec, D.; Muller, A.S.; Broschinski, S.; Politi, M.C. Numbers can be worth a thousand pictures: Individual differences in understanding graphical and numerical representations of health-related information. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kakkilaya, V.; Groome, L.J.; Platt, D.; Kurepa, D.; Pramanik, A.; Caldito, G.; Conrad, L.; Bocchini, J.A.; Davis, T.C. Use of a visual aid to improve counseling at the threshold of viability. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e1511–e1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Retamero, R.; Cokely, E.T. Designing visual aids that promote risk literacy: A systematic review of health research and evidence-based design heuristics. Hum. Factors 2017, 59, 582–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.; Andrade, A.D.; García-Retamero, R.; Anam, R.; Rodríguez, R.; Lisigurski, M.; Sharit, J.; Ruiz, J.G. Health literacy, numeracy, and graphical literacy among veterans in primary care and their effect on shared decision making and trust in physicians. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdel-Kader, K.; Dew, M.A.; Bhatnagar, M.; Argyropoulos, C.; Karpov, I.; Switzer, G.; Unruh, M.L. Numeracy skills in CKD: Correlates and outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osborn, C.Y.; Cavanaugh, K.; Wallston, K.A.; Rothman, R.L. Self-efficacy links health literacy and numeracy to glycemic control. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckelberg, A.; Hulfenhaus, C.; Haastert, B.; Muhlhauser, I. Effect of evidence based risk information on “informed choice” in colorectal cancer screening: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011, 342, d3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DNEM e.V. Guideline Evidence-Based Health Information. 2016. Available online: https://www.leitlinie-gesundheitsinformation.de/?lang=en (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.M.; Vogt, D. Health literacy in the German population. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2017, 114, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paivio, A.; Rogers, T.B.; Smythe, P.C. Why are pictures easier to recall than words? Psychon. Sci. 1986, 11, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, D.C.; Puglisi, J.T.; Sovacool, M. Memory for pictures, words, and spatial location in older adults: Evidence for pictorial superiority. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, R.N. Recognition memory for words, sentences, andpictures. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1967, 6, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckelberg, A.; Meyer, G.; Mühlhauser, I. Correspondence (letter to the editor): Questionnaire should not be used any longer. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2017, 114, 330. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).