Interdisciplinary Care Networks in Rehabilitation Care for Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Databases Searched and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

- Assessment (a systematic approach to ensuring that the health service uses its resources to improve the health of the population most efficiently) [31];

- Education—basic knowledge (anatomy, biomechanics, the function of the body, and pathophysiology) [32];

- Education—knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics (information on prevention, cause of pain, ergonomics, information on posture, information on activity, exercise) [32];

- Education—knowledge of treatment (self-management, lifestyle modification, information on coping with the problems) [32];

- Manual Therapy (passive joint mobilization and massage therapy) [33];

- Specific Exercise Therapy (active and/or active-assisted strengthening, mobilizing, and stretching exercises to restore the function of the affected region) [34];

- General Exercise Therapy (aerobic and resistance training, causing an increase in energy expenditure, to maintain health-related outcomes) [35];

- Mind-Body Exercise Therapy (to enhance the mind’s capacity to positively affect bodily functions and symptoms, including pain, by combining exercises with mental focus) [36];

- Workplace intervention (a set of comprehensive health promotion and occupational health strategies implemented in the workplace to improve work-related outcomes) [42];

- Anesthetics (local anesthetics for diagnosis and therapy, indications include functional disorders, inflammatory diseases, and acute and chronic pain) [43];

- Medication management (a systematic process of ensuring that the patient’s medication regimen is optimally appropriate, effective, and safe, and that the patient is adhering to this regimen to promote health and reduce the need for health care use) [44].

2.4. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

3. Results

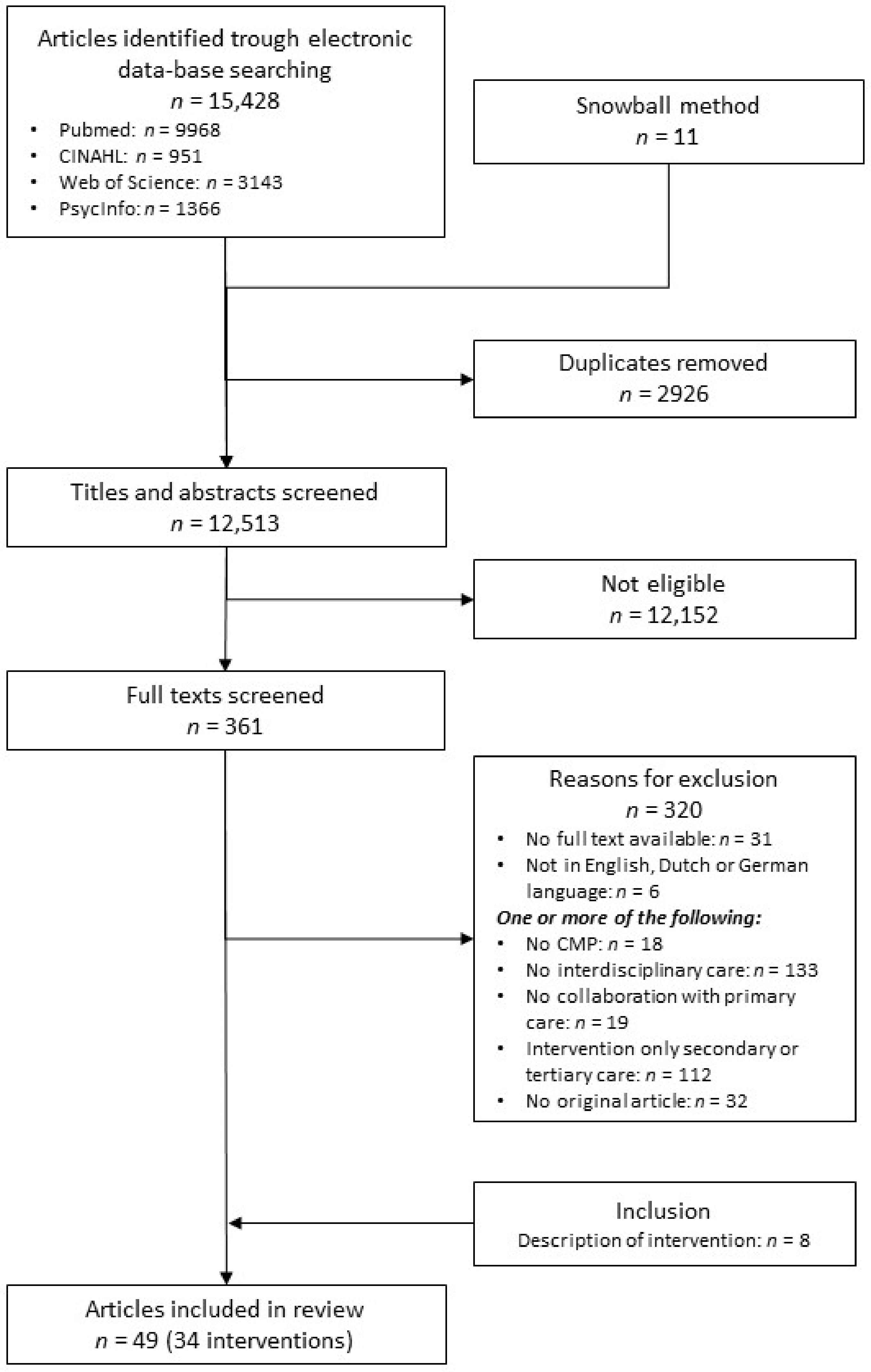

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Quadruple Aim Outcomes

3.2.1. Within Primary Care—Randomized Trial Designs

3.2.2. Within Primary Care—Non-Randomized Study Designs

3.2.3. Within Primary Care—Qualitative Designs

3.2.4. Between Primary Care and Secondary or Tertiary Care—Randomized Trial Designs

3.2.5. Between Primary Care and Secondary or Tertiary Care—Non-Randomized Trial Designs

3.2.6. In Primary Care and between Primary Care and Secondary or Tertiary Care—Randomized Trial Design

3.2.7. Between Primary Care and Social Care—Randomized Trial Design

3.2.8. Between Primary Care and Social Care—Non-Randomized Study Design

3.2.9. Between Primary Care and Secondary or Tertiary Care and Social Care—Randomized Trial Designs

3.2.10. Between Primary Care and Community-Based Care—Randomized Trial Designs

3.2.11. Between Primary Care and Community-Based Care—Qualitative Designs

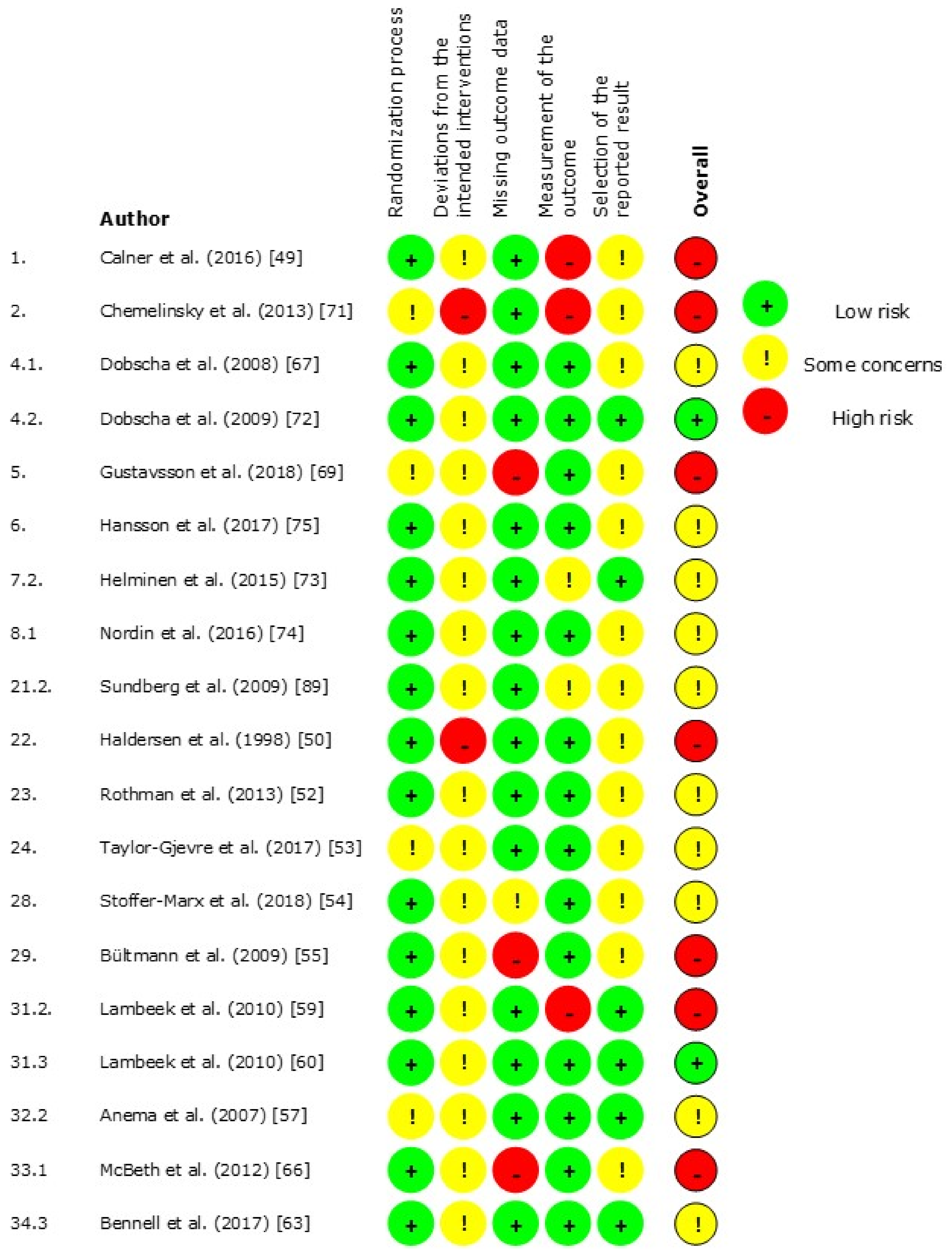

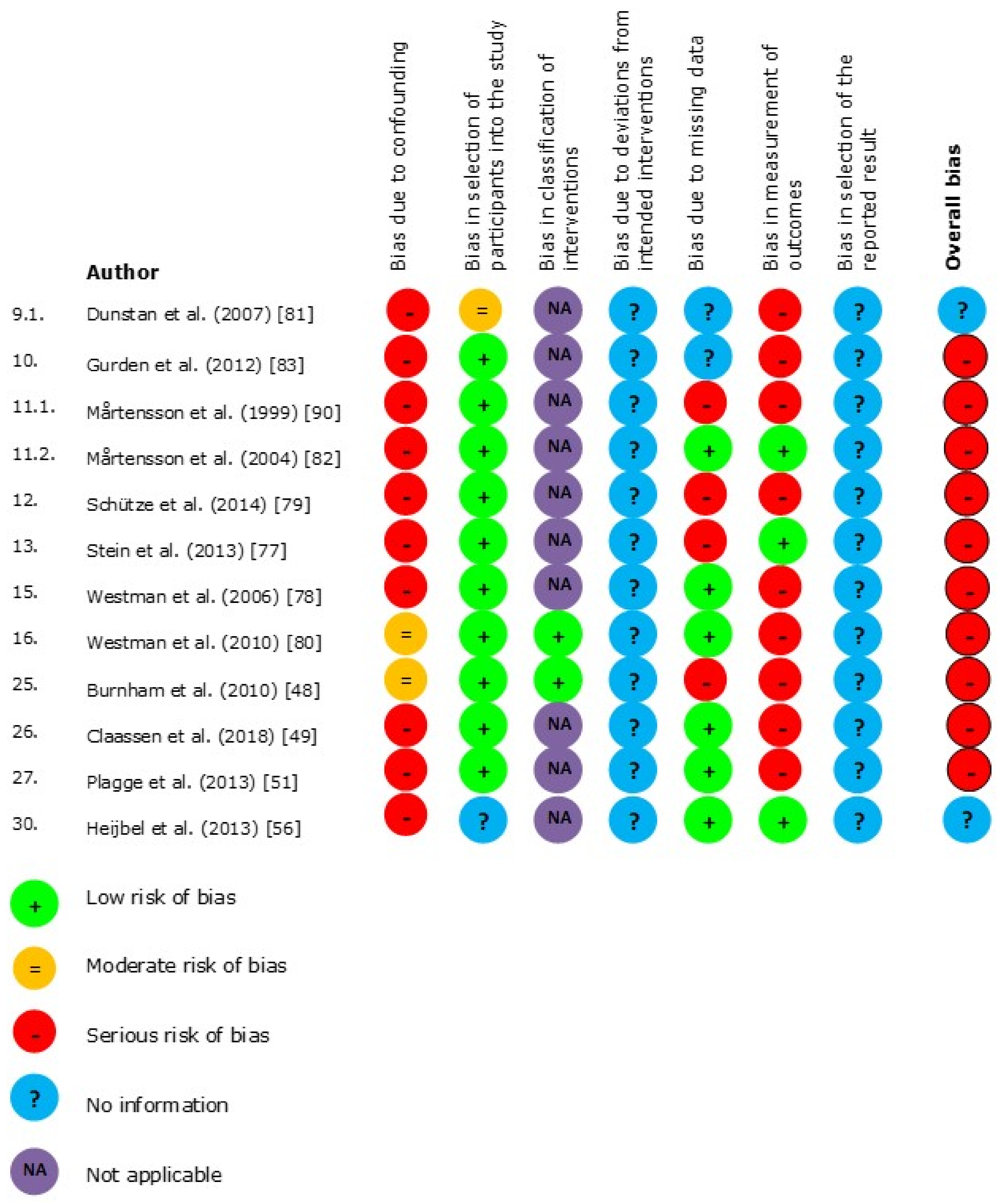

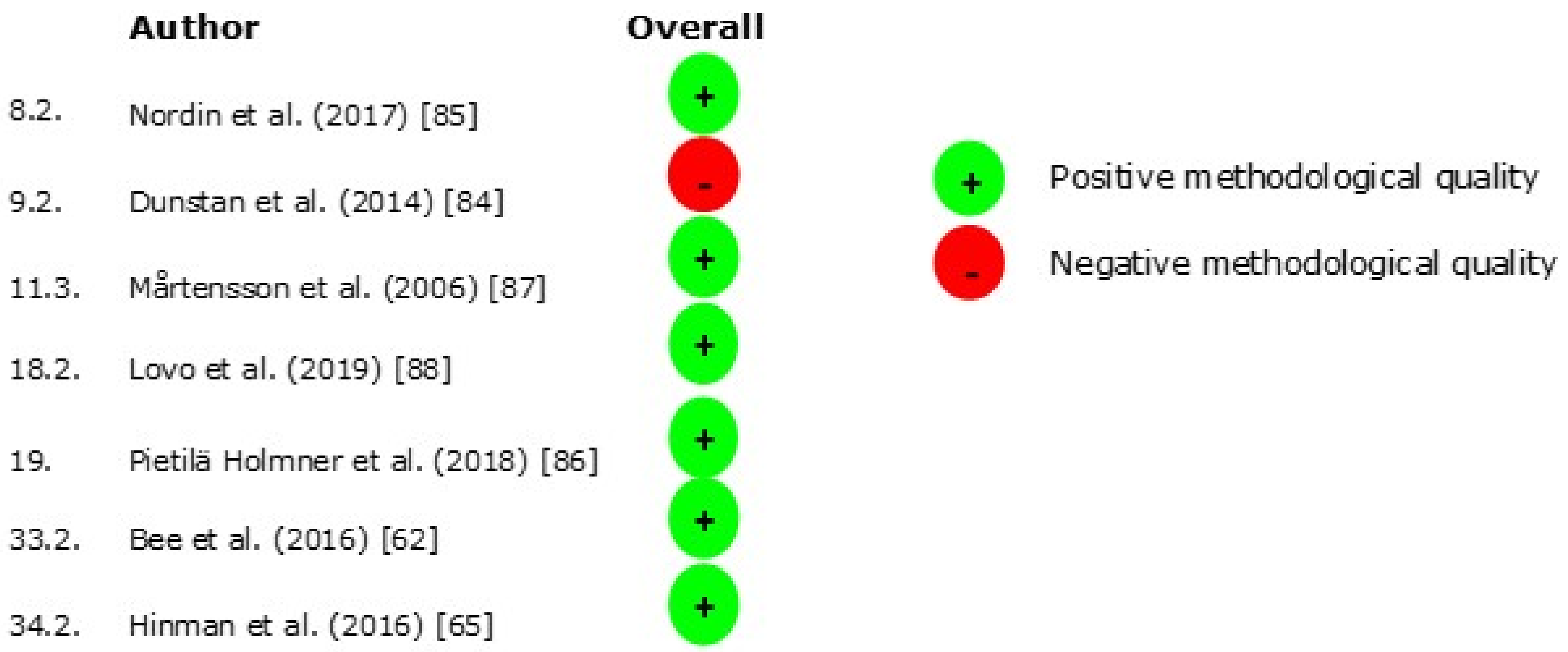

3.3. Risk of Bias

3.4. Randomized Trial Designs

3.5. Non-Randomized Study Designs

3.6. Qualitative Designs

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Future Innovations and Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Literature Searches

| Patient | (((Pain[MeSH:NoExp] OR Pain*[tiab] OR Ache*[tiab]) AND (chronic*[tiab] OR back[tiab] OR musculoskeletal*[tiab] OR Neck[tiab] OR cervical*[tiab] OR lumb*[tiab] OR ankle*[tiab] OR knee*[tiab] OR wrist*[tiab] OR elbow*[tiab] OR shoulder*[tiab] OR hip[tiab] OR pelvic girdle[tiab] OR Physical Suffering*[tiab])) OR Arthralgia[MESH] OR arthralgia*[tiab] OR polyarthralgia*[tiab] OR Muscular Rheumatism[tiab] OR Lumbago[tiab] OR Fibromyalgi*[tiab] OR Neckache*[tiab] OR complex regional pain syndrome[tiab] OR regional pain[tiab] OR Arthritis[MeSH] OR Arthriti*[tiab] OR osteoarthr*[tiab]) |

| AND | |

| Intervention | (((interdisciplin*[tiab] OR integrat*[tiab] OR intersect*[tiab] OR transmural[tiab] OR multidisciplinar*[tiab] OR chain*[tiab] OR Comprehensive[tiab] OR deliver*[tiab] OR network*[tiab] OR coordinat*[tiab] OR collaboration*[tiab] OR level*[tiab] OR appropriate[tiab] OR outpatient[tiab] OR ambulatory[tiab] OR Patient focused[tiab] OR transition*[tiab]) AND (healthcare[tiab] OR care[tiab] OR health care[tiab] OR service*[tiab] OR system*[tiab])) OR Patient Care Management [MeSH:NoExp] OR patient care management [tiab] OR comprehensive health care[MeSH] OR Delivery of Health Care[MeSH] OR pain management[MeSH] OR Pain Management*[tiab] OR integrated delivery system*[tiab] OR managed clinical network*[tiab] OR Intersectoral Collaboration*[tiab] OR managed care[tiab] OR shared care[tiab]) |

| AND | |

| Comparison | ((Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine[MESH] OR physical and rehabilitation medicine[tiab] OR rehabilitation [MESH] OR rehabilitation[tiab] OR Physical Therapy Specialty[MeSH] OR physical therap*[tiab] OR Physical Therapy Modalities[MeSH] OR Physical Therapy Modalit*[tiab] OR occupational therapy[MeSH] OR Occupational Therap*[tiab] OR Physiatry[tiab] OR Habilitation[tiab] OR physiotherap*[tiab] OR biopsychosocial[tiab] OR exercise therapy[tiab])) |

| AND | |

| Outcome | (Quadruple Aim[tiab] OR Triple Aim[tiab] OR health outcome*[tiab] OR quality of health care[MeSH] OR quality of healthcare[tiab] OR Population health[MeSH] OR population health[tiab] OR Quality of Life[MeSH] OR quality of life[tiab] OR treatment Outcome[MeSH] OR treatment outcome*[tiab] OR Clinical Effect*[tiab] OR Rehabilitation Outcome*[tiab] OR Treatment Efficacy[tiab] OR Experienced health[tiab] OR HRQOL[tiab] OR health related quality of life[tiab] OR life quality[tiab] OR patient satisfaction[MeSH] OR patient satisfaction*[tiab] OR Consumer Satisfaction[tiab] OR patient experience*[tiab] OR meaning in work[tiab] OR meaningful work[tiab] OR workforce engagement[tiab] OR work pressure[tiab] OR job satisfaction[MeSH] OR job satisfaction*[tiab] OR work satisfaction[MeSH] OR work satisfaction*[tiab] OR workforce satisfaction[tiab] OR Health care costs[MeSH] OR Health Care Cost*[tiab] OR Health Expenditures[MeSH] OR Health Expenditure*[tiab] OR Cost-Benefit Analysis[MeSH] OR Cost-Benefit Analys*[tiab] OR Costs and Cost Analysis[MeSH] OR Costs and cost analys*[tiab] OR cost effect*[tiab] OR Costs[tiab]) |

| AND | |

| Time | (“1994/11/1”[Date-Publication]: “3000”[Date-Publication]) |

| Final | #6,”Search (((((((((Pain[MeSH:NoExp] OR Pain*[tiab] OR Ache*[tiab]) AND (chronic*[tiab] OR back[tiab] OR musculoskeletal*[tiab] OR Neck[tiab] OR cervical*[tiab] OR lumb*[tiab] OR ankle*[tiab] OR knee*[tiab] OR wrist*[tiab] OR elbow*[tiab] OR shoulder*[tiab] OR hip[tiab] OR pelvic girdle[tiab] OR Physical Suffering*[tiab])) OR Arthralgia[MESH] OR arthralgia*[tiab] OR polyarthralgia*[tiab] OR Muscular Rheumatism[tiab] OR Lumbago[tiab] OR Fibromyalgi*[tiab] OR Neckache*[tiab] OR complex regional pain syndrome[tiab] OR regional pain[tiab] OR Arthritis[MeSH] OR Arthriti*[tiab] OR osteoarthr*[tiab])))) AND (((((interdisciplin*[tiab] OR integrat*[tiab] OR intersect*[tiab] OR transmural[tiab] OR multidisciplinar*[tiab] OR chain*[tiab] OR Comprehensive[tiab] OR deliver*[tiab] OR network*[tiab] OR coordinat*[tiab] OR collaboration*[tiab] OR level*[tiab] OR appropriate[tiab] OR outpatient[tiab] OR ambulatory[tiab] OR Patient focused[tiab] OR transition*[tiab]) AND (healthcare[tiab] OR care[tiab] OR health care[tiab] OR service*[tiab] OR system*[tiab])) OR Patient Care Management [MeSH:NoExp] OR patient care management [tiab] OR comprehensive health care[MeSH] OR Delivery of Health Care[MeSH] OR pain management[MeSH] OR Pain Management*[tiab] OR integrated delivery system*[tiab] OR managed clinical network*[tiab] OR Intersectoral Collaboration*[tiab] OR managed care[tiab] OR shared care[tiab])))) AND ((((Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine[MESH] OR physical and rehabilitation medicine[tiab] OR rehabilitation [MESH] OR rehabilitation[tiab] OR Physical Therapy Specialty[MeSH] OR physical therap*[tiab] OR Physical Therapy Modalities[MeSH] OR Physical Therapy Modalit*[tiab] OR occupational therapy[MeSH] OR Occupational Therap*[tiab] OR Physiatry[tiab] OR Habilitation[tiab] OR physiotherap*[tiab] OR biopsychosocial[tiab] OR exercise therapy[tiab]))))) AND (((Quadruple Aim[tiab] OR Triple Aim[tiab] OR health outcome*[tiab] OR quality of health care[MeSH] OR quality of healthcare[tiab] OR Population health[MeSH] OR population health[tiab] OR Quality of Life[MeSH] OR quality of life[tiab] OR treatment Outcome[MeSH] OR treatment outcome*[tiab] OR Clinical Effect*[tiab] OR Rehabilitation Outcome*[tiab] OR Treatment Efficacy[tiab] OR Experienced health[tiab] OR HRQOL[tiab] OR health related quality of life[tiab] OR life quality[tiab] OR patient satisfaction[MeSH] OR patient satisfaction*[tiab] OR Consumer Satisfaction[tiab] OR patient experience*[tiab] OR meaning in work[tiab] OR meaningful work[tiab] OR workforce engagement[tiab] OR work pressure[tiab] OR job satisfaction[MeSH] OR job satisfaction*[tiab] OR work satisfaction[MeSH] OR work satisfaction*[tiab] OR workforce satisfaction[tiab] OR Health care costs[MeSH] OR Health Care Cost*[tiab] OR Health Expenditures[MeSH] OR Health Expenditure*[tiab] OR Cost-Benefit Analysis[MeSH] OR Cost-Benefit Analys*[tiab] OR Costs and Cost Analysis[MeSH] OR Costs and cost analys*[tiab] OR cost effect*[tiab] OR Costs[tiab])))) AND (““1994/11/1”“[Date-Publication]: ““3000”“[Date-Publication])”,9968,07:24:25 |

| Patient | (((TI Pain OR AB Pain) OR (TI Ache OR AB ache)) AND ((TI chronic OR AB chronic) OR (TI back OR AB back) OR (TI musculoskeletal OR AB musculoskeletal) OR (TI Neck OR AB neck) OR (TI cervical OR AB cervical) OR (TI lumb OR AB lumb) OR (TI ankle OR AB ankle) OR (TI knee OR AB knee) OR (TI wrist OR AB wrist) OR (AB elbow OR TI elbow) OR (TI shoulder OR AB shoulder) OR (TI hip OR AB hip) OR (TI pelvic girdle OR AB pelvic girdle) OR (TI Physical Suffering OR AB physical suffering))) OR TI Arthralgia OR AB arthralgia OR TI polyarthralgia OR AB polyarthralgia OR TI Muscular Rheumatism OR AB muscular rheumatism OR TI Lumbago OR AB lumbago OR TI Fibromyalgia OR AB fibromyalgia OR TI Neckache OR AB neckache OR TI complex regional pain syndrome OR AB complex regional pain syndrome OR TI regional pain OR AB regional pain OR TI Arthritis OR AB arthritis OR TI osteoarthritis OR AB osteoarthritis |

| AND | |

| Intervention | ((TI interdisciplinary OR AB interdisciplinary OR TI integrated OR AB integrated OR TI intersection OR AB intersection OR TI transmural OR AB transmural OR TI multidisciplinary OR AB multidisciplinary OR TI chain OR AB chain OR TI Comprehensive OR AB Comprehensive OR TI delivery OR AB delivery OR TI network OR AB network OR TI coordination OR AB coordination OR TI collaboration OR AB collaboration OR TI level OR AB level OR TI levels OR AB levels OR TI appropriate OR AB appropriate OR TI outpatient OR AB outpatient OR TI ambulatory OR AB ambulatory OR TI Patient focused OR AB patient focused OR TI transition OR AB transition) AND (TI healthcare OR AB healthcare OR TI care OR AB care OR TI health care OR AB health care OR TI service OR AB service OR TI system OR AB system)) OR TI Patient Care Management OR AB patient care management OR TI patient care management OR AB patient care management OR TI comprehensive health care OR AB comprehensive health care OR TI Delivery of Health Care OR AB delivery of health care OR TI pain management OR AB pain management OR TI integrated delivery system OR AB integrated delivery system OR TI managed clinical network OR AB managed clinical network OR TI Intersectoral Collaboration OR AB intersectoral collaboration OR TI managed care OR AB managed care OR TI shared care OR AB shared care |

| AND | |

| Comparison | (TI Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine AB physical and rehabilitation medicine OR TI rehabilitation OR AB rehabilitation OR TI Physical Therapy Specialty OR AB physical therapy specialty OR TI Physical Therapy Modalities OR AB Physical Therapy Modalities OR TI occupational therapy OR AB occupational therapy OR TI Physiatry OR AB physiatry OR TI Habilitation OR AB habilitation OR TI physiotherapy OR AB physiotherapy OR TI biopsychosocial OR AB biopsychosocial OR TI exercise therapy OR AB exercise therapy) |

| AND | |

| Outcome | TI Quadruple Aim OR AB quadruple aim OR TI Triple Aim OR AB triple aim OR TI health outcome OR AB health outcome OR TI quality of health care OR AB quality of healthcare OR TI Population health OR AB population health OR TI Quality of Life OR AB quality of life OR TI treatment Outcome OR AB treatment outcome OR TI Clinical Effect OR AB clinical effect OR TI Rehabilitation Outcome OR AB rehabilitation outcome OR TI Treatment Efficacy OR AB treatment efficacy OR TI Experienced health OR AB experienced health OR TI HRQOL OR AB HRQOL OR TI health related quality of life OR AB health related quality of life OR TI life quality OR AB life quality OR TI patient satisfaction OR AB patient satisfaction OR TI Consumer Satisfaction OR AB consumer satisfaction OR TI patient experience OR AB patient experience OR AB meaning in work OR TI meaning in work OR TI meaningful work OR AB meaningful work OR TI workforce engagement OR AB workforce engagement OR TI work pressure OR AB work pressure OR TI job satisfaction OR AB job satisfaction OR TI work satisfaction OR AB work satisfaction OR TI workforce satisfaction OR AB workforce satisfaction OR TI Health care costs OR AB Health Care Costs OR TI Health Expenditures OR AB Health Expenditures OR TI Cost-Benefit Analysis OR AB Cost-Benefit Analysis OR TI Costs and Cost Analysis OR AB Costs and cost analysis OR TI cost effectivity OR AB cost effectivity OR TI Costs OR AB costs |

| AND | |

| Time | DT 1994–2019 |

| (((TI Pain OR AB Pain) OR (TI Ache OR AB ache)) AND ((TI chronic OR AB chronic) OR (TI back OR AB back) OR (TI musculoskeletal OR AB musculoskeletal) OR (TI Neck OR AB neck) OR (TI cervical OR AB cervical) OR (TI lumb OR AB lumb) OR (TI ankle OR AB ankle) OR (TI knee OR AB knee) OR (TI wrist OR AB wrist) OR (AB elbow OR TI elbow) OR (TI shoulder OR AB shoulder) OR (TI hip OR AB hip) OR (TI pelvic girdle OR AB pelvic girdle) OR (TI Physical Suffering OR AB physical suffering))) OR TI Arthralgia OR AB arthralgia OR TI polyarthralgia OR AB polyarthralgia OR TI Muscular Rheumatism OR AB muscular rheumatism OR TI Lumbago OR AB lumbago OR TI Fibromyalgia OR AB fibromyalgia OR TI Neckache OR AB neckache OR TI complex regional pain syndrome OR AB complex regional pain syndrome OR TI regional pain OR AB regional pain OR TI Arthritis OR AB arthritis OR TI osteoarthritis OR AB osteoarthritis) AND (((TI interdisciplinary OR AB interdisciplinary OR TI integrated OR AB integrated OR TI intersection OR AB intersection OR TI transmural OR AB transmural OR TI multidisciplinary OR AB multidisciplinary OR TI chain OR AB chain OR TI Comprehensive OR AB Comprehensive OR TI delivery OR AB delivery OR TI network OR AB network OR TI coordination OR AB coordination OR TI collaboration OR AB collaboration OR TI level OR AB level OR TI levels OR AB levels OR TI appropriate OR AB appropriate OR TI outpatient OR AB outpatient OR TI ambulatory OR AB ambulatory OR TI Patient focused OR AB patient focused OR TI transition OR AB transition) AND (TI healthcare OR AB healthcare OR TI care OR AB care OR TI health care OR AB health care OR TI service OR AB service OR TI system OR AB system)) OR TI Patient Care Management OR AB patient care management OR TI patient care management OR AB patient care management OR TI comprehensive health care OR AB comprehensive health care OR TI Delivery of Health Care OR AB delivery of health care OR TI pain management OR AB pain management OR TI integrated delivery system OR AB integrated delivery system OR TI managed clinical network OR AB managed clinical network OR TI Intersectoral Collaboration OR AB intersectoral collaboration OR TI managed care OR AB managed care OR TI shared care OR AB shared care) AND ((TI Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine AB physical and rehabilitation medicine OR TI rehabilitation OR AB rehabilitation OR TI Physical Therapy Specialty OR AB physical therapy specialty OR TI Physical Therapy Modalities OR AB Physical Therapy Modalities OR TI occupational therapy OR AB occupational therapy OR TI Physiatry OR AB physiatry OR TI Habilitation OR AB habilitation OR TI physiotherapy OR AB physiotherapy OR TI biopsychosocial OR AB biopsychosocial OR TI exercise therapy OR AB exercise therapy)) AND (TI Quadruple Aim OR AB quadruple aim OR TI Triple Aim OR AB triple aim OR TI health outcome OR AB health outcome OR TI quality of health care OR AB quality of healthcare OR TI Population health OR AB population health OR TI Quality of Life OR AB quality of life OR TI treatment Outcome OR AB treatment outcome OR TI Clinical Effect OR AB clinical effect OR TI Rehabilitation Outcome OR AB rehabilitation outcome OR TI Treatment Efficacy OR AB treatment efficacy OR TI Experienced health OR AB experienced health OR TI HRQOL OR AB HRQOL OR TI health related quality of life OR AB health related quality of life OR TI life quality OR AB life quality OR TI patient satisfaction OR AB patient satisfaction OR TI Consumer Satisfaction OR AB consumer satisfaction OR TI patient experience OR AB patient experience OR AB meaning in work OR TI meaning in work OR TI meaningful work OR AB meaningful work OR TI workforce engagement OR AB workforce engagement OR TI work pressure OR AB work pressure OR TI job satisfaction OR AB job satisfaction OR TI work satisfaction OR AB work satisfaction OR TI workforce satisfaction OR AB workforce satisfaction OR TI Health care costs OR AB Health Care Costs OR TI Health Expenditures OR AB Health Expenditures OR TI Cost-Benefit Analysis OR AB Cost-Benefit Analysis OR TI Costs and Cost Analysis OR AB Costs and cost analysis OR TI cost effectivity OR AB cost effectivity OR TI Costs OR AB costs) Limiters-Published Date: 19941101–20191131 Expanders-Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes-Boolean/Phrase |

| Patient | (((Pain* OR Ache*) AND (chronic* OR musculoskeletal* OR Neck OR cervical* OR lumb* OR ankle* OR knee* OR wrist* OR elbow* OR shoulder* OR hip* OR pelvic girdle OR Physical Suffering*)) OR arthralgia* OR polyarthralgia* OR “Muscular Rheumatism*” OR Lumbago OR Fibromyalgi* OR Neckache* OR “complex regional pain syndrome” OR “regional pain” OR Arthriti* OR osteoarthritis) |

| AND | |

| Intervention | (((interdisciplinary OR integrated OR intersectoral OR transmural OR multidisciplinary OR chain* OR Comprehensive OR deliver* OR network* OR coordination OR collaboration* OR level* OR appropriate OR outpatient OR ambulatory OR Patient focused OR transitional) AND (healthcare OR care OR health care OR service* OR system*)) OR “Patient Care Management” OR “comprehensive health care” OR “Delivery of Health Care” OR “pain management” OR “integrated delivery system*” OR “managed clinical network*” OR “Intersectoral Collaboration*” OR “managed care” OR “shared care”) |

| AND | |

| Comparison | (“Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine” OR rehabilitation OR “Physical Therapy Specialty” OR “physical therap*” OR “Physical Therapy Modalit*” OR “occupational therap*” OR Physiatr* OR Habilitation OR physiotherap* OR biopsychosocial treatment OR “exercise therapy”) |

| AND | |

| Outcome | (“Quadruple Aim” OR “Triple Aim” OR health outcome* OR “quality of health care” OR “quality of healthcare” OR “Population health” OR “Quality of Life” OR “treatment Outcome” OR “Clinical Effect*” OR “Rehabilitation Outcome*” OR “Treatment Efficacy” OR “Experienced health” OR HRQOL OR “health related quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “patient satisfaction” OR “Consumer Satisfaction” OR “patient experience*” OR “meaning in work” OR “meaningful work” OR “workforce engagement” OR “work pressure” OR “job satisfaction” OR “work satisfaction” OR “workforce satisfaction” OR “Health care cost*” OR “Health Expenditure*” OR “Cost-Benefit Analys*” OR “Costs and Cost Analys*” OR “cost effect*” OR Costs) |

| AND | |

| Time | 1994–2019 |

| TOPIC: ((((Pain* OR Ache*) AND (chronic* OR musculoskeletal* OR Neck OR cervical* OR lumb* OR ankle* OR knee* OR wrist* OR elbow* OR shoulder* OR hip* OR pelvic girdle OR Physical Suffering*)) OR arthralgia* OR polyarthralgia* OR “Muscular Rheumatism*” OR Lumbago OR Fibromyalgi* OR Neckache* OR “complex regional pain syndrome” OR “regional pain” OR Arthriti* OR osteoarthritis)) AND TOPIC: ((((interdisciplinary OR integrated OR intersectoral OR transmural OR multidisciplinary OR chain* OR Comprehensive OR deliver* OR network* OR coordination OR collaboration* OR level* OR appropriate OR outpatient OR ambulatory OR Patient focused OR transitional) AND (healthcare OR care OR health care OR service* OR system*)) OR “Patient Care Management” OR “comprehensive health care” OR “Delivery of Health Care” OR “pain management” OR “integrated delivery system*” OR “managed clinical network*” OR “Intersectoral Collaboration*” OR “managed care” OR “shared care”)) AND TOPIC: ((“Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine” OR rehabilitation OR “Physical Therapy Specialty” OR “physical therap*” OR “Physical Therapy Modalit*” OR “occupational therap*” OR Physiatr* OR Habilitation OR physiotherap* OR biopsychosocial treatment OR “exercise therapy”)) AND TOPIC: ((“Quadruple Aim” OR “Triple Aim” OR health outcome* OR “quality of health care” OR “quality of healthcare” OR “Population health” OR “Quality of Life” OR “treatment Outcome” OR “Clinical Effect*” OR “Rehabilitation Outcome*” OR “Treatment Efficacy” OR “Experienced health” OR HRQOL OR “health related quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “patient satisfaction” OR “Consumer Satisfaction” OR “patient experience*” OR “meaning in work” OR “meaningful work” OR “workforce engagement” OR “work pressure” OR “job satisfaction” OR “work satisfaction” OR “workforce satisfaction” OR “Health care cost*” OR “Health Expenditure*” OR “Cost-Benefit Analys*” OR “Costs and Cost Analys*” OR “cost effect*” OR Costs)) Timespan: 1994–2019. Indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, ESCI. |

| Patient | (((Pain* OR Ache*) AND (chronic* OR musculoskeletal* OR Neck OR cervical* OR lumb* OR ankle* OR knee* OR wrist* OR elbow* OR shoulder* OR hip* OR pelvic girdle OR Physical Suffering*)) OR arthralgia* OR polyarthralgia* OR “Muscular Rheumatism*” OR Lumbago OR Fibromyalgi* OR Neckache* OR “complex regional pain syndrome” OR “regional pain” OR Arthriti* OR osteoarthritis) |

| AND | |

| Intervention | (((interdisciplinary OR integrated OR intersectoral OR transmural OR multidisciplinary OR chain* OR Comprehensive OR deliver* OR network* OR coordination OR collaboration* OR level* OR appropriate OR outpatient OR ambulatory OR Patient focused OR transitional) AND (healthcare OR care OR health care OR service* OR system*)) OR “Patient Care Management” OR “comprehensive health care” OR “Delivery of Health Care” OR “pain management” OR “integrated delivery system*” OR “managed clinical network*” OR “Intersectoral Collaboration*” OR “managed care” OR “shared care”) |

| AND | |

| Comparison | (“Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine” OR rehabilitation OR “Physical Therapy Specialty” OR “physical therap*” OR “Physical Therapy Modalit*” OR “occupational therap*” OR Physiatr* OR Habilitation OR physiotherap* OR biopsychosocial OR “exercise therapy”) |

| AND | |

| Outcome | (“Quadruple Aim” OR “Triple Aim” OR health outcome* OR “quality of health care” OR “quality of healthcare” OR “Population health” OR “Quality of Life” OR “treatment Outcome” OR “Clinical Effect*” OR “Rehabilitation Outcome*” OR “Treatment Efficacy” OR “Experienced health” OR HRQOL OR “health related quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “patient satisfaction” OR “Consumer Satisfaction” OR “patient experience*” OR “meaning in work” OR “meaningful work” OR “workforce engagement” OR “work pressure” OR “job satisfaction” OR “work satisfaction” OR “workforce satisfaction” OR “Health care cost*” OR “Health Expenditure*” OR “Cost-Benefit Analys*” OR “Costs and Cost Analys*” OR “cost effect*” OR Costs) |

| AND | |

| Time | 1994–2019 |

| ((Pain* OR Ache*) AND (chronic* OR musculoskeletal* OR Neck OR cervical* OR lumb* OR ankle* OR knee* OR wrist* OR elbow* OR shoulder* OR hip* OR pelvic girdle OR Physical Suffering*)) OR arthralgia* OR polyarthralgia* OR “Muscular Rheumatism*” OR Lumbago OR Fibromyalgi* OR Neckache* OR “complex regional pain syndrome” OR “regional pain” OR Arthriti* OR osteoarthritis)) AND ((((interdisciplinary OR integrated OR intersectoral OR transmural OR multidisciplinary OR chain* OR Comprehensive OR deliver* OR network* OR coordination OR collaboration* OR level* OR appropriate OR outpatient OR ambulatory OR Patient focused OR transitional) AND (healthcare OR care OR health care OR service* OR system*)) OR “Patient Care Management” OR “comprehensive health care” OR “Delivery of Health Care” OR “pain management” OR “integrated delivery system*” OR “managed clinical network*” OR “Intersectoral Collaboration*” OR “managed care” OR “shared care”)) AND ((“Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine” OR rehabilitation OR “Physical Therapy Specialty” OR “physical therap*” OR “Physical Therapy Modalit*” OR “occupational therap*” OR Physiatr* OR Habilitation OR physiotherap* OR biopsychosocial OR “exercise therapy”)) AND ((“Quadruple Aim” OR “Triple Aim” OR health outcome* OR “quality of health care” OR “quality of healthcare” OR “Population health” OR “Quality of Life” OR “treatment Outcome” OR “Clinical Effect*” OR “Rehabilitation Outcome*” OR “Treatment Efficacy” OR “Experienced health” OR HRQOL OR “health related quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “patient satisfaction” OR “Consumer Satisfaction” OR “patient experience*” OR “meaning in work” OR “meaningful work” OR “workforce engagement” OR “work pressure” OR “job satisfaction” OR “work satisfaction” OR “workforce satisfaction” OR “Health care cost*” OR “Health Expenditure*” OR “Cost-Benefit Analys*” OR “Costs and Cost Analys*” OR “cost effect*” OR Costs)) Limiters-Published Date: 19941101–20191131 Expanders-Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes-Boolean/Phrase |

References

- Breivik, H.; Collett, B.; Ventafridda, V.; Cohen, R.; Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain 2006, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieza, A.; Causey, K.; Kamenov, K.; Hanson, S.W.; Chatterji, S.; Vos, T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 396, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.P.; Jöud, A.; Bergknut, C.; Croft, P.; Edwards, J.J.; Peat, G.; Petersson, I.F.; Turkiewicz, A.; Wilkie, R.; Englund, M. International comparisons of the consultation prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions using population-based healthcare data from England and Sweden. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 73, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskin, D.J.; Richard, P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J. Pain 2012, 13, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breivik, H.; Eisenberg, E.; O’Brien, T. The individual and societal burden of chronic pain in Europe: The case for strategic prioritisation and action to improve knowledge and availability of appropriate care. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkering, G.E.; Bala, M.M.; Reid, K.; Kellen, E.; Harker, J.; Riemsma, R.; Huygen, F.J.P.M.; Kleijnen, J. Epidemiology of chronic pain and its treatment in The Netherlands. Neth. J. Med. 2011, 69, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, D.G.; Smith, E.; Cross, M.; Sanchez-Riera, L.; Buchbinder, R.; Blyth, F.M.; Brooks, P.; Woolf, A.D.; Osborne, R.H.; Fransen, M.; et al. The global burden of musculoskeletal conditions for 2010: An overview of methods. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P.M. The burden of musculoskeletal disease—A global perspective. Clin. Rheumatol. 2006, 25, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.; Mattke, S.; Perrault, P.J.; Wagner, E.H. Untangling practice redesign from disease management: How do we best care for the chronically ill? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2009, 30, 385–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.; Knickman, J.R. Changing the chronic care system to meet people’s needs. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.H.; Torrance, N. Management of chronic pain in primary care. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2011, 5, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfield, B.; Shi, L.; Macinko, J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 457–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.A.; Wagner, E.H. Chronic illness management: What is the role of primary care? Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 138, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckxstaens, P.; Maeseneer, J.; Sutter, A. The role of general practitioners and family physicians in the management of multimorbidity. In Comorbidity of Mental and Physical Disorders; Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation in Health Systems; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel, R.J.; Peng, Y.B.; Peters, M.L.; Fuchs, P.N.; Turk, D.C. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 581–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Guzman, J.; Van Tulder, M.W. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD000963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, R.J.; McGeary, D.D.; Peterson, A.; Moore, M.; LeRoy, K.; Isler, W.C.; Hryshko-Mullen, A.S.; Edell, T. Preliminary findings of a randomized controlled trial of an interdisciplinary military pain program. Mil. Med. 2009, 174, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanos, S.; Houle, T.T. Multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary management of chronic pain. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 17, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association for the Study of Pain Terminology Working Group. Classification of Chronic Pain, 2nd ed.; IASP: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673&.navItemNumber=677 (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Berwick, D.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Whittington, J. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alleva, A.; Leigheb, F.; Rinaldi, C.; Di Stanislao, F.; Vanhaecht, K.; De Ridder, D.; Bruyneel, L.; Cangelosi, G.; Panella, M. Achieving quadruple aim goals through clinical networks: A systematic review. J. Health Qual. Res. 2019, 34, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, N.; Zamora, K.; Tighe, J.; Li, Y.; Douraghi, M.; Seal, K. The integrated pain team: A mixed-methods evaluation of the impact of an embedded interdisciplinary pain care intervention on primary care team satisfaction, confidence, and perceptions of care effectiveness. Pain Med. 2017, 19, 1748–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzelthin, S.F.; Daniëls, R.; Van Rossum, E.; Cox, K.; Habets, H.; De Witte, L.P.; Kempen, G.I. A nurse-led interdisciplinary primary care approach to prevent disability among community-dwelling frail older people: A large-scale process evaluation. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1184–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.D.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.F.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Wright, J.; Williams, R.; Wilkinson, J.R. Health needs assessment: Development and importance of health needs assessment. Br. Med. J. 1998, 316, 1310–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainpradub, K.; Sitthipornvorakul, E.; Janwantanakul, P.; van der Beek, A.J. Effect of education on non-specific neck and low back pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Man. Ther. 2016, 22, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egmond, D.L.; Schuitemaker, R.; Mink, A.J.F. Extremiteiten: Manuele Therapie in Enge en Ruime Zin; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McNeely, M.L.; Campbell, K.; Ospina, M.; Rowe, B.H.; Dabbs, K.; Klassen, T.P.; Mackey, J.; Courneya, K. Exercise interventions for upper-limb dysfunction due to breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2010, CD005211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.I.; Scherer, R.W.; Geigle, P.M.; Berlanstein, D.R.; Topaloglu, O.; Gotay, C.C.; Snyder, C. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD007566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husebø, A.M.L.; Husebø, T.L. Quality of life and breast cancer: How can mind-body exercise therapies help? An overview study. Sports 2017, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, I.; Öhlund, C.; Eek, C.; Wallin, L.; Peterson, L.-E.; Fordyce, W.E.; Nachemson, A.L. The effect of graded activity on patients with subacute low back pain: A randomized prospective clinical study with an operant-conditioning behavioral approach. Phys. Ther. 1992, 72, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J.; Hellsing, A.-L.; Andersson, D. A controlled study of the effects of an early intervention on acute musculoskeletal pain problems. Pain 1993, 54, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; De Vet, H.C.W.; Berfelo, M.W.; Kerckhoffs, M.R.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Wolters, P.M.J.C.; Brandt, P.A.V.D. Effectiveness of behavioral graded activity after first-time lumbar disc surgery: Short term results of a randomized controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 2003, 12, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordyce, W.E.; Fowler, R.S.; Lehmann, J.F.; DeLateur, B.J.; Sand, P.L.; Trieschmann, R.B. Operant conditioning in the treatment of chronic pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1973, 54, 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Haazen, I.W.C.J.; Schuerman, J.A.; Kole-Snijders, A.M.J.; Eek, H. Behavioural rehabilitation of chronic low back pain: Comparison of an operant treatment, an operant-cognitive treatment and an operant-respondent treatment. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 34, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Population Health National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Workplace Health Model. 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/model/index.html (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Egli, S.; Pfister, M.; Ludin, S.M.; De La Vega, K.P.; Busato, A.; Fischer, L. Long-term results of therapeutic local anesthesia (neural therapy) in 280 referred refractory chronic pain patients. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrin, K.; Chan, F.; Pagoria, N.; Jolson-Oakes, S.; Uyeno, R.; Levin, A. A statewide medication management system: Health information exchange to support drug therapy optimization by pharmacists across the continuum of care. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br. Med. J. 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br. Med. J. 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools, Checklist for Qualitative Research; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, R.; Day, J.; Dudley, W. Multidisciplinary chronic pain management in a rural Canadian setting. Can. J. Rural Med. 2010, 15, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Claassen, A.A.O.M.; Schers, H.J.; Koëter, S.; Van Der Laan, W.H.; Kremers-van de Hei, K.C.A.L.C.; Botman, J.; Busch, V.J.J.F.; Rijnen, W.H.C.; van den Ende, C.H.M. Preliminary effects of a regional approached multidisciplinary educational program on healthcare utilization in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: An observational study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorsen, E.M.; Kronholm, K.; Skouen, J.S.; Ursin, H. Multimodal cognitive behavioral treatment of patients sicklisted for musculoskeletal pain: A randomized controlled study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1998, 27, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Plagge, J.M.; Lu, M.W.; Lovejoy, T.I.; Karl, A.I.; Dobscha, S.K. Treatment of comorbid pain and PTSD in returning veterans: A collaborative approach utilizing behavioral activation. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, M.G.; Ortendahl, M.; Rosenblad, A.; Johansson, A.C. Improved quality of life, working ability, and patient satisfaction after a pretreatment multimodal assessment method in patients with mixed chronic muscular pain: A randomized-controlled study. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Gjevre, R.; Nair, B.; Bath, B.; Okpalauwaekwe, U.; Sharma, M.; Penz, E.; Trask, C.; Stewart, S.A. Addressing rural and remote access disparities for patients with inflammatory arthritis through video-conferencing and innovative inter-professional care models. Musculoskelet. Care 2018, 16, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffer-Marx, M.A.; Klinger, M.; Luschin, S.; Meriaux-Kratochvila, S.; Zettel-Tomenendal, M.; Nell-Duxneuner, V.; Zwerina, J.; Kjeken, I.; Hackl, M.; Öhlinger, S.; et al. Functional consultation and exercises improve grip strength in osteoarthritis of the hand—A randomised controlled trial. Arthritis Res. 2018, 20, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bültmann, U.; Sherson, D.; Olsen, J.; Hansen, C.L.; Lund, T.; Kilsgaard, J. Coordinated and tailored work rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial with economic evaluation undertaken with workers on sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2009, 19, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijbel, B.; Josephson, M.; Vingård, E. Implementation of a rehabilitation model for employees on long-term sick leave in the public sector: Difficulties, counter-measures, and outcomes. Work 2013, 45, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anema, J.R.; Steenstra, I.A.; Bongers, P.M.; de Vet, H.C.; Knol, D.L.; Loisel, P.; van Mechelen, W. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for subacute low back pain: Graded activity or workplace intervention or both? A randomized controlled trial. Spine 2007, 32, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeek, L.C.; Anema, J.R.; Van Royen, B.J.; Buijs, P.C.; Wuisman, P.I.; Van Tulder, M.W.; Van Mechelen, W. Multidisciplinary outpatient care program for patients with chronic low back pain: Design of a randomized controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study [ISRCTN28478651]. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambeek, L.C.; Bosmans, J.E.; Van Royen, B.J.; Van Tulder, M.W.; Van Mechelen, W.; Anema, J.R. Effect of integrated care for sick listed patients with chronic low back pain: Economic evaluation alongside a randomised controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 2010, 341, c6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeek, L.C.; Van Mechelen, W.; Knol, D.L.; Loisel, P.; Anema, J.R. Randomised controlled trial of integrated care to reduce disability from chronic low back pain in working and private life. Br. Med. J. 2010, 340, c1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenstra, I.A.; Anema, J.R.; Bongers, P.M.; De Vet, H.C.W.; Van Mechelen, W. Cost effectiveness of a multi-stage return to work program for workers on sick leave due to low back pain, design of a population based controlled trial [ISRCTN60233560]. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2003, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bee, P.; McBeth, J.; Macfarlane, G.J.; Lovell, K. Managing chronic widespread pain in primary care: A qualitative study of patient perspectives and implications for treatment delivery. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, K.L.; Campbell, P.K.; Egerton, T.; Metcalf, B.; Kasza, J.; Forbes, A.; Bills, C.; Gale, J.; Harris, A.; Kolt, G.S.; et al. Telephone coaching to enhance a home-based physical activity program for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2017, 69, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, K.L.; Egerton, T.; Bills, C.; Gale, J.; Kolt, G.S.; Bunker, S.J.; Hunter, D.J.; Brand, C.A.; Forbes, A.; Harris, A.; et al. Addition of telephone coaching to a physiotherapist-delivered physical activity program in people with knee osteoarthritis: A randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, R.S.; Delany, C.M.; Campbell, P.K.; Gale, J.; Bennell, K.L. Physical therapists, telephone coaches, and patients with knee osteoarthritis: Qualitative study about working together to promote exercise adherence. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBeth, J.; Prescott, G.; Scotland, G.; Lovell, K.; Keeley, P.; Hannaford, P.; McNamee, P.; Symmons, D.P.M.; Woby, S.; Gkazinou, C.; et al. Cognitive behavior therapy, exercise, or both for treating chronic widespread pain. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobscha, S.K.; Corson, K.; Leibowitz, R.Q.; Sullivan, M.D.; Gerrity, M.S. Rationale, design, and baseline findings from a randomized trial of collaborative care for chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care. Pain Med. 2008, 9, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, B.; Grona, S.L.; Milosavljevic, S.; Sari, N.; Imeah, B.; O’Connell, M.E. Advancing interprofessional primary health care services in rural settings for people with chronic low back disorders: Protocol of a community-based randomized controlled trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, C.; Nordlander, J.; Söderlund, A. Activity and life-role targeting rehabilitation for persistent pain: Feasibility of an intervention in primary healthcare. Eur. J. Physiother. 2018, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calner, T.; Nordin, C.; Eriksson, M.; Nyberg, L.; Gard, G.; Michaelson, P. Effects of a self-guided, web-based activity programme for patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain in primary healthcare: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelimsky, T.C.; Fischer, R.L.; Levin, J.B.; Cheren, M.I.; Marsh, S.K.; Janata, J.W. The primary practice physician Program for Chronic Pain (© 4PCP): Outcomes of a primary physician-pain specialist collaboration for community-based training and support. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobscha, S.K.; Corson, K.; Perrin, N.A.; Hanson, G.C.; Leibowitz, R.Q.; Doak, M.N.; Dickinson, K.C.; Sullivan, M.D.; Gerrity, M.S. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: A cluster randomized trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009, 301, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, E.-E.; Sinikallio, S.H.; Valjakka, A.L.; Väisänen-Rouvali, R.H.; Arokoski, J.P.A. Effectiveness of a cognitive–behavioural group intervention for knee osteoarthritis pain: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 868–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, C.A.; Michaelson, P.; Gard, G.; Eriksson, M.K.; Gustavsson, C.; Buhrman, M. Effects of the web behavior change program for activity and multimodal pain rehabilitation: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, E.E.; Sörensson, E.; Ronnheden, A.-M.; Lundgren, M.; Bjärnung, A.; Dahlberg, L.E. Arthritis school in primary health care. A pilot study of 14 years of experiences from Malmo. Lakartidningen 2008, 105, 2175–2177. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, T.; Halpin, J.; Warenmark, A.; Falkenberg, T. Towards a model for integrative medicine in Swedish primary care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBar, L.; Benes, L.; Bonifay, A.; Deyo, R.A.; Elder, C.R.; Keefe, F.J.; Leo, M.C.; McMullen, C.; Mayhew, M.; Owen-Smith, A.; et al. Interdisciplinary team-based care for patients with chronic pain on long-term opioid treatment in primary care (PPACT)—Protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2018, 67, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, E.-E.; Sinikallio, S.H.; Valjakka, A.L.; Väisänen-Rouvali, R.H.; Arokoski, J.P. Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral group intervention for knee osteoarthritis pain: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, C.; Michaelson, P.; Eriksson, M.K.; Gard, G. It’s about me: Patients’ experiences of patient participation in the web behavior change program for activity in combination with multimodal pain rehabilitation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.A.; Covic, T. Can a rural community-based work-related activity program make a difference for chronic pain-disabled injured workers? Aust. J. Rural Health 2007, 15, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.A. Participants’ evaluation of a brief intervention for pain-related work disability. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2014, 37, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurden, M.; Morelli, M.; Sharp, G.; Baker, K.; Betts, N.; Bolton, J. Evaluation of a general practitioner referral service for manual treatment of back and neck pain. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2012, 13, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, L.; Marklund, B.; Fridlund, B. Evaluation of a biopsychosocial rehabilitation programme in primary healthcare for chronic pain patients. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 1999, 6, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson, L.; Marklund, B.; Baigi, A.; Gunnarsson, M.; Fridlund, B. Long-term influences of a biopsychosocial rehabilitation programme for chronic pain patients. Musculoskelet. Care 2004, 2, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, L.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. Experiences of a primary health care rehabilitation programme. A focus group study of persons with chronic pain. Disabil. Rehabil. 2006, 28, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütze, R.; Slater, H.; O’Sullivan, P.; Thornton, J.; Finlay-Jones, A.; Rees, C.S. Mindfulness-based functional therapy: A preliminary open trial of an integrated model of care for people with persistent low back pain. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 839. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, K.F.; Miclescu, A. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit. Scand. J. Pain 2013, 4, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, Z.; Frakes, K.-A.; Cornwell, P.; Kuys, S.S.; Barnett, A.G.; McPhail, S.M. The health outcomes and costs of people attending an interdisciplinary chronic disease service in regional Australia: Protocol for a longitudinal cohort investigation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, A.; Linton, S.J.; Theorell, T.; Öhrvik, J.; Wåhlén, P.; Leppert, J. Quality of life and maintenance of improvements after early multimodal rehabilitation: A 5-year follow-up. Disabil. Rehabil. 2006, 28, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, A.; Linton, S.J.; Öhrvik, J.; Wahlén, P.; Theorell, T.; Leppert, J. Controlled 3-year follow-up of a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation program in primary health care. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 32, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorflinger, L.M.; Ruser, C.; Sellinger, J.; Edens, E.L.; Kerns, R.D.; Becker, W.C. integrating interdisciplinary pain management into primary care: Development and implementation of a novel clinical program. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 2046–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovo, S.; Harrison, L.; O’Connell, M.E.; Trask, C.; Bath, B. Experience of patients and practitioners with a team and technology approach to chronic back disorder management. J. Multidiscip. Health 2019, 12, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmner, E.P.; Stålnacke, B.-M.; Enthoven, P.; Stenberg, G. “The acceptance” of living with chronic pain—An ongoing process: A qualitative study of patient experiences of multimodal rehabilitation in primary care. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, G.; Holmner, E.P.; Stålnacke, B.-M.; Enthoven, P. Healthcare professional experiences with patients who participate in multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary care—A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, T.; Petzold, M.; Wändell, P.; Ryden, A.; Falkenberg, T. Exploring integrative medicine for back and neck pain—A pragmatic randomised clinical pilot trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2009, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjel, T.C.C.; Spreeuwenberg, M.D.; Struijs, J.N.; Baan, C.A.; Ruwaard, D. Substituting hospital-based outpatient cardiology care: The impact on quality, health and costs. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibbald, B.; Pickard, S.; McLeod, H.; Reeves, D.; Mead, N.; Gemmell, I.; Coast, J.; Roland, M.; Leese, B. Moving specialist care into the community: An initial evaluation. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2008, 13, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocon, A.; Rhodes, P.J.; Wright, J.P.; Eastham, J.; Williams, D.R.R.; Harrison, S.R.; Young, R.J. Specialist general practitioners and diabetes clinics in primary care: A qualitative and descriptive evaluation. Diabet. Med. 2004, 21, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obucina, M.; Harris, N.; Fitzgerald, J.; Chai, A.; Radford, K.; Ross, A.; Carr, L.; Vecchio, N. The application of triple aim framework in the context of primary healthcare: A systematic literature review. Health Policy 2018, 122, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerman, N.; Kidd, S.A. The healthcare triple aim in the recovery era. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 47, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.; Joanne, O.; Froud, R.; Underwood, M.; Seers, K. The work of return to work. Challenges of returning to work when you have chronic pain: A meta-ethnography. Br. Med. J. Open 2019, 9, e025743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, A.D.; Zhao, J.; Voth, J.; Hassan, S.; Dubin, R.; Stinson, J.N.; Jaglal, S.; Fabico, R.; Smith, A.J.; Taenzer, P.; et al. Evaluation of an innovative tele-education intervention in chronic pain management for primary care clinicians practicing in underserved areas. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skamagki, G.; King, A.; Duncan, M.; Wåhlin, C. A systematic review on workplace interventions to manage chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Physiother. Res. Int. 2018, 23, e1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, R.; King-VanVlack, C. The trajectory of chronic pain: Can a community-based exercise/education program soften the ride? Pain Res. Manag. 2010, 15, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Integreated health services—What and why? In Technical Brief; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Br. Med. J. 2014, 348, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| An intervention for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) of the posture- and locomotion apparatus. Studies were also included if the study population was a mix of patients with subacute and chronic complaints. | An intervention developed for headache or stomach-ache, or only for patients with subacute pain (<12 weeks). |

| Rehabilitation care enabling individuals aged ≥18 years to maintain or return to their daily life activities, fulfill meaningful life roles and maximize their well-being [30]. The goal of the rehabilitation is on the improvement of participation or functioning of the patient. | A (rehabilitation) intervention which was designed for pre-post surgery care, or if it consisted of eHealth, which substitutes the treatment given by an HCP, or if the intervention only focuses on medication prescription or use. |

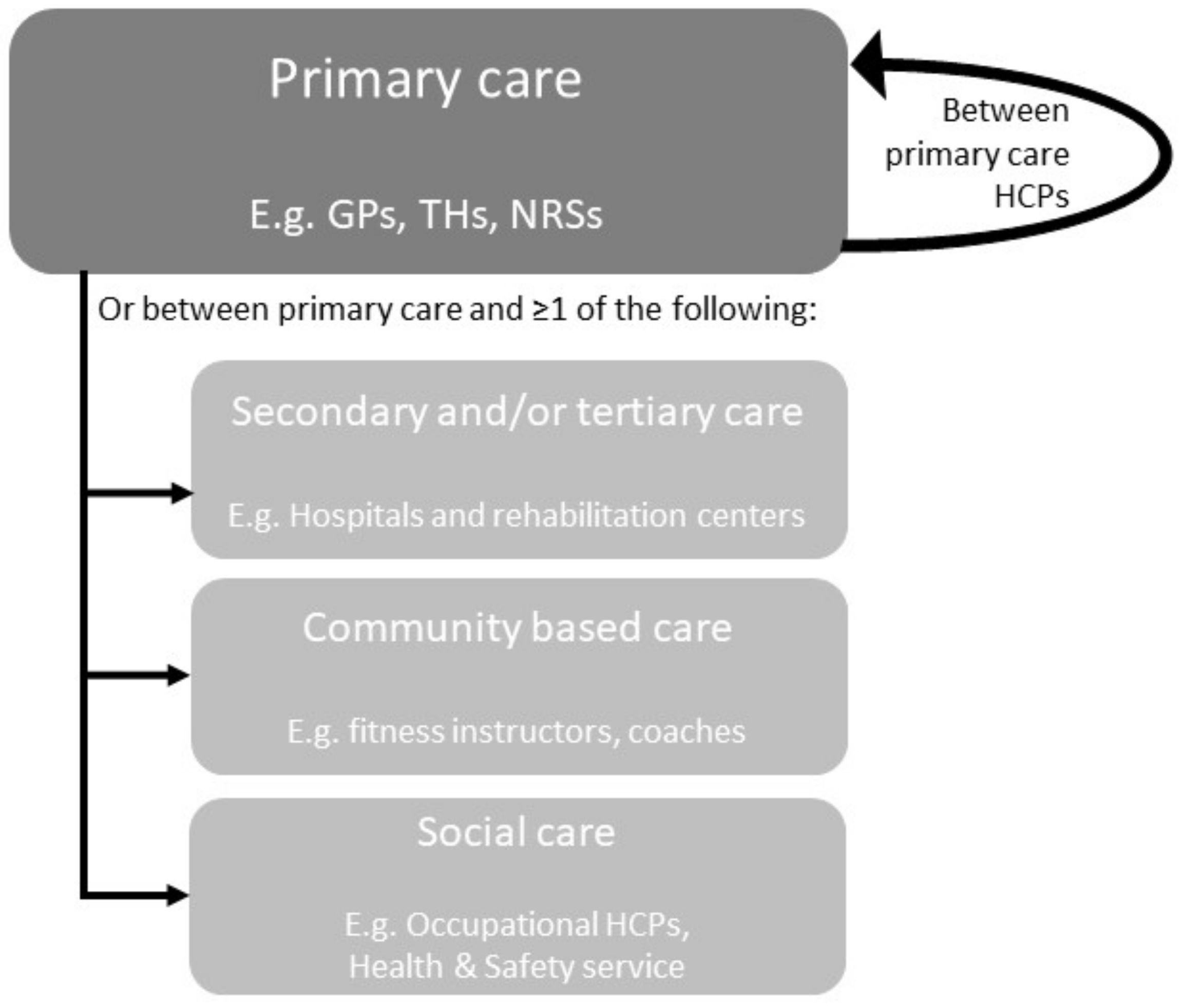

| An interdisciplinary care network based on the IASP definition [21]: a multimodal treatment provided by a multidisciplinary team collaborating in assessment and/or treatment using a shared biopsychosocial model and goals. The HCPs all have to work closely together with regular team meetings (face to face or online), agreement on the diagnosis, therapeutic aims and plans for treatment and review. There was a bidirectional discussion or exchange of treatment approaches with the same goal between HCPs of different disciplines (e.g., a GP with a physiotherapist). | An intervention in which HCPs of different disciplines treated a patient but without a mutual goal, bidirectional discussion, or exchange of treatment approaches. An intervention that focuses only on the referral or triage of patients without collaboration during the treatment itself. An intervention with only extended practices roles, e.g., the physiotherapist takes over the roles of the GP. |

| Implemented within primary care or between primary care and other healthcare settings (secondary or tertiary care, social care, or community-based care) (see Figure 1) | Interventions implemented within or between secondary or tertiary clinic(s). |

| Original descriptions of (results of) an intervention, such as protocol articles, feasibility studies, process evaluations, and qualitative and quantitative (cost)-effectiveness studies. | A review or guideline. The references for these studies were checked for eligible articles. |

| Only full texts which were available in Dutch, English, or German. | |

| Articles published between 1 January 1994 and 14 November 2019. |

| No. | Author, Year & Country | Intervention Name | Target Population | Collaboration | Content and Intensity Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within primary care | |||||

| Randomized trial designs | |||||

| 1 | Calner et al., (2016) [49] * Intervention is linked to interventions of Nordin (number 8) Sweden | Multimodal pain Rehabilitation (MMR) & web behaviour change program for activity (Web-BCPA) | Chronic musculoskeletal pain of the back, neck, shoulders, and/or a generalized pain condition | PH THs PSY or PSY-C NRS 1× Team discussion with patient about treatment plan | MMR ≥2×/w, ≥6 w At least 3 different healthcare professionals Specific Exercise Therapy General Exercise Therapy Manual Therapy Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Web-BCPA 24 h, 7 d, 16 w Self-guided by the patient Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of treatment Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| 2 | Chelimsky et al., (2013) [71] US | Primary Practice Physician Program for Chronic Pain (4PCP) | Chronic Pain (back pain 51.9%, fibromyalgia 23.1%, neck pain 6.7%, others) | PH PSY THs | * No separate intervention for patients Collaborative training of PHs consisting of: Active learning: Evidence-based active learning seminars, self-directed learning Clinical support: to collaborate with the interdisciplinary treatment team comprising pain-informed THs and PSY providing cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| 3 | DeBar et al., (2018) [77] USA | Pain Program for Active Coping and Training (PPACT) | Chronic pain On opioid treatment (≥6 m) On health plan | PPACT interventionist team: PSY-C NCM PCPs: PS PR PPACT interventionists and PCPs meetings for treatment plan (before start treatment) and evaluation (end of treatment) | Comprehensive intake evaluation NCM or PSY-C Assessment Medication management 1 × TS Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)-based pain coping skills training and adapted movement practice 12 w (group) Cognitive-behavioral therapy PCP consultation and patient outreach By NCM and PSY-C |

| 4 | 1: Dobscha et al., (2008) [67] 2: Dobscha et al., (2009) [72] USA | Study of the Effectiveness of a Collaborative Approach to Pain (SEACAP) | Musculoskeletal pain Chronic Exclusion: fibromyalgia | PSY: care manager IT: intervention & workshop teacher TH: workshop teacher Discussion between PSY and IT about assessment results and treatment recommendations. These are sent by email to clinicians. Leading workshop with PSY and IT or TH. | Telephone contact Written materials Education—Basic knowledge Assessment by PSY Assessment Education—Knowledge of treatment Recommendation treatment plan Based on discussions about symptoms or additional education by PSY and IT Workshop 90 m, 4×, 4 months By PSY, co-led by IT or TH Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment |

| 5 | Gustavsson et al., (2018) [69] Sweden | Activity and life-role targeting rehabilitation (ALAR) | Musculoskeletal pain Chronic | TSs PH PSY-C TSs: Participating in education meetings about treatment protocol and behavioral medicine approach, 3×,4 h MMR: team discussions about assessment and treatment plan | Multimodal pain rehabilitation (MMR) Content and intensity are patient dependent Assessment Cognitive-behavioral therapy ALAR + MMR 1 h, 10×, 10 w Workbook and therapist for goal setting Assessment Education—Knowledge of treatment Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| 6 | Hansson et al., (2010) [75] Sweden | Patient education program for osteoarthritis (PEPOA) | OA in hip, knee or hand | THs OS NRS DT Providing PEPOA | PEPOA (n = 8–10) 3 h, 5×, 1×/w, 5 w Education—Knowledge of treatment |

| 7 | 1: Helminen et al., (2013) [78] 2: Helminen et al., (2015) [73] Finland | Cognitive-behavioural (CB) intervention for OA | Knee pain Chronic | PSY TH Providing CB intervention | Cognitive Behavioral group intervention (n = 8–10): 1×/w, 2 h, 6 w Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment Mind-Body Exercise Therapy |

| 8 | 1: Nordin et al., (2016) [74] 2:Nordin et al., (2017) [79] Sweden | Web Behavior Change Program for Activity (Web-BCPA) added to multimodal pain rehabilitation (MMR) | Pain in the back, neck, shoulder, and/or generalized pain | NRS THs PH PSY PSY-C PH for contact with the team and Swedish Social Insurance Agency | MMR 2–3×/w, 6–8 w By ≥3 disciplines Specific Exercise Therapy General Exercise Therapy Manual Therapy Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment Cognitive-behavioral therapy Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Web-BCPA 16 w Self-guided Cognitive-behavioral therapy Education—Knowledge of treatment |

| Non-randomized trial designs | |||||

| 9 | 1: Dunstan et al., (2007) [80] 2: Dunstan et al., (2014) [81] Australia | Light multidisciplinary Work-Related Activity Program (WRAP) | Musculoskeletal pain Chronic | PSY TH GP ORP | WRAP (n = 30, 7 groups) 4 h, 1×/w, 6 w By PSY and TH providing treatment, GP as medical case-manager, and ORP as a return-to-work case manager Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Specific Exercise Therapy General Exercise Therapy Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Workplace intervention |

| 10 | Gurden et al., (2012) [82] UK | North East Essex Primary Care Trust manual therapy service | Back or Neck pain Subacute and chronic | GP CH THs Prescribed treatment plan Advise during referral after treatment (TH to GP) | GP consultation Assessment Education—Basic knowledge Medication management Manual therapy (within 2 weeks) max. 6× CH, TSs Manual Therapy Discharge with a report to GP |

| 11 | 1: Mårtensson et al., (1999) [83] 2: Mårtensson et al., (2004) [84] 3: Mårtensson et al., (2006) [85] Sweden | Biopsychosocial rehabilitation programme, Focus on Health (FoH) | Pain Chronic | GP NRS THs PSY-C Teaching in FoH program | FoH Group sessions (n = 5–9) 2×/w, 6 w: 6 × 6 h + 6 × 3 h Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Education—Knowledge of treatment Ergonomics Individual introductory and concluding conversation for activity and locomotion analysis |

| 12 | Schütze et al., (2014) [86] Australia | Mindfulness-Based Functional Therapy (MBFT) | LBP Chronic | PSY TH Co-facilitated sessions | MBFT-group session (n = 6 & n = 10) 2 h/w, 8 w Education—Knowledge of treatment Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| 13 | Stein et al., (2013) [87] Sweden | Multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation (MDR) | Musculoskeletal pain Chronic | GP PSY THs Examination report of GP visible by all Team meeting about biopsychosocial motivation to participate Providing treatment | MDR Group sessions (n = 6–8): 5 h, 3 d/w, 6 w GP (12 h) Education—Basic knowledge Mind-Body Exercise Therapy TH (18 h) Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Mind-Body Exercise Therapy TH (20 h) Specific Exercise Therapy Cognitive-behavioral therapy Mind-Body Exercise Therapy PSY (28 h) Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment Cognitive-behavioral therapy Additional education (12 h), provided by Swedish Insurance Agency, Swedish Employment Agency, local fitness center, dietary adviser |

| 14 | Tyack et al., (2013) [88] Australia | Student-led interdisciplinary chronic disease health service | Back pain Chronic | NRS PO THs Exercise PSY PSY-C SP DT PR Indigenous health worker Case conference and service delivery | Intake by 1 HCP and 2 students Assessment Case conference By the team Selection of appropriate services Services from one or more HCP 3–6 months |

| 15 | Westman et al., (2006) [89] Sweden | STAR project; multimodal rehabilitation program | Musculoskeletal pain Chronic Sick listed | PSY PH TH A representative from the National Insurance Company Team discussions about treatment plan | STAR project group based (n = 8–10) 3.5 h/d, 5 d, 8 w General Exercise Therapy Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Creative activities Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment Individual (when necessary): Physiotherapy or psychotherapy or orthopedic consultation |

| 16 | Westman et al., (2010) [90] Sweden | Multidisciplinary rehabilitation program | Musculoskeletal pain Chronic Sick listed | GP TH PSY or PSY-C Team discussions about diagnosis and treatment plan | Assessment and deciding treatment program 1×/w By the team Assessment And one or more of the following interventions: Multimodal Group (n = 6–8) 4 h/d, 4 d, 6 w General Exercise Therapy Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Creative activities Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment Three-way communication Patient, GP/PSY or PSY-C Adjustments of treatment plan Individual TH or PSY or orthopedic consultation Workplace-based intervention Workplace intervention |

| Qualitative designs | |||||

| 17 | 1:Dorflinger et al., (2014) [91] 2: Purcell et al., (2018) [25] USA | Integrated Pain Team (ITP) | Pain Chronic | PH and/or NP PSY PR Team discussions about diagnosis and treatment plan Providing treatment Keeping track of treatments (inside and outside ITP) | ITP existing of: 3×, 2–3 m, n = 15–20/m Interdisciplinary Assessment 1 h by complete team and patient Assessment Education—Basic knowledge Medication management During complete follow-up by ITP Medication management Additional Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—knowledge of treatment Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| 18 | 1: Bath et al., (2016) [65] 2: Lovo et al., (2019) [92] Canada | Secure video conferencing/telehealth | LBP Chronic | TH (urban-based) NP (local rural) 1× Digital assessment | Digital assessment 1× NP at patient side performing a physical examination Assessment Education—Knowledge of treatment |

| 19 | Pietilä Holmner et al., (2018) [93] Sweden | Multimodal rehabilitation (MMR) | Pain Chronic Sick listed (or at risk) | THs PH PSY Team discussions about assessment and treatment | MMR Individual and/or group intervention General Exercise Therapy Mind-Body Exercise Therapy Education—Knowledge of treatment |

| 20 | Stenberg et al., (2016) [94] Sweden | Multimodal rehabilitation (MMR) | Pain Chronic Sick listed (or at risk) | THs PSY-C PSY GP DT NRS THs deliver treatment. Other members deliver treatment or have a consultation function | MMR By THs and optionally ≥1 of the other HCPs Group, individually, or combination Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| 21 | 1: Sundberg et al., (2007) [76] 2: Sundberg et al., (2009) [95] Sweden | Integrative medicine (IM) management | Back or Neck pain Mixed population subacute and chronic | GP Senior CT providers Team discussions about treatment plan | IM Conventional therapies, advise by GP Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Anaesthetics General Exercise Therapy Complementary therapies by CT providers 10×, 12 w Manual Therapy |

| Between primary care and secondary or tertiary care | |||||

| Randomized trial designs | |||||

| 22 | Haldorsen et al., (1998) [50] Norway | Multimodal Cognitive Behavioral Treatment (MMCBT) | Back, neck, shoulder pain, generalized muscle pain, more localized musculoskeletal disorders Subacute and chronic Sick listed | NEU GP PSY Registered NRS TH Team discussions on diagnosis and treatment plan Providing treatment (e.g., Education) | Multidisciplinary rehabilitation 6 h, 5×/w, 4 w Combination of group and individual treatment Assessment Specific Exercise Therapy General Exercise Therapy Individual by TH Cognitive-behavioral therapy (8×) Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment 2× lectures and discussions by all healthcare professionals Workplace interventions By physician, human resource officer, occupational counsellor, representative of a governmental social insurance authority. |

| 23 | Rothman et al., (2013) [52] Sweden | Multidisciplinary, multimodal (MM), multi-professional assessment | CMP Chronic | GP And ≥3: NRS PSY TH PSY-C OS when necessary: liaison PH at the Psychosomatic Medicine Clinic (PMC) Interdisciplinary team meeting about assessment | Assessment in the MM Group Each discipline had 1 meeting with patient (mean 7 sessions) Conference meeting to give treatment advice:

|

| 24 | Taylor-Gjevre et al., (2017) [53] Canada | Video-conferencing | RA | Urban-based RT On-site TH Performing assessment and follow-up care | Video-conferencing treatment 4× TH is at patient side for physical examination and set up conferencing with the rheumatologist who is performing the assessment and follow-up care Assessment |

| Non-randomized trial designs | |||||

| 25 | Burnham et al., (2010) [48] Canada | Central Alberta Pain and Rehabilitation Institute (CAPRI) program | Pain Chronic | PH TH GP PSY NRS DT KN Team discussions about treatment plan Executing of treatment (full multidisciplinary management) | Referral documentation review GP Initial assessment 1: spine care assessment: 1,5 h, by PH and TH 2: medical care assessment (optional): 2 h, by GP Assessment Treatment (1 of the options) I-1: Consultation only: education, activity modification, and a customized home exercise program Education General exercise therapy I-2: Interventional management: anaesthetic block by PH Anaesthetics I-3: Supervised medication management: by GP Medication management I-4: Full multidisciplinary management (n = 4–6): 5 h, 1×/w, 2–3 months, the whole team Group discussions about education and treatment plan Psychotherapy Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of treatment |

| 26 | Claassen et al., (2018) [49] The Netherlands | Osteoarthritis (OA) education | OA in hip or knee | GP TH OS or NP Public health advisor (when available) Teaching in OA educational program | OA educational program (n = 10–12) 1,5 h, 2× Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Basic knowledge Education—Knowledge of treatment Booklet Information, monitoring forms, course handout, 20 FAQs, a pedometer, and a list of websites and contact information |

| 27 | Plagge et al., (2013) [51] USA | Integrated Management of Pain and PTSD in Returning OEF/OIF/ONDVEterans (IMPPROVE) | Pain Chronic Posttraumatic stress disorder Veterans | PSY PH Discussions about assessment and weekly telephone meetings about treatment | Biopsychosocial evaluation 90 min by PSY Assessment Care management 1×/w by PSY and PH Reviewing recommendations with veterans, assessing interest and willingness to engage in recommended treatments, discussing concerns or questions, coordination of care between services, facilitating communication between the veteran and providers, helping veterans navigate the VA system, monitoring treatment plans Behavioral Activation Psychotherapy 8×, 75–90 min Individual by PSY Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| In primary care and between primary care and secondary or tertiary care | |||||

| Randomized trial design | |||||

| 28 | Stoffer-Marx et al., (2018) [54] Austria | The combined intervention | OA in hand Chronic | RT THs NRS DT They have primary or specialized care setting expertise (or both) Two deliver treatment together | Baseline assessment By blinded assessor Assessment The combined intervention Individual treatment 7×/w, 8 w By 2 HCPs Specific Exercise Therapy Medication management Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Education—Knowledge of treatment |

| Between primary care and social care | |||||

| Randomized trial designs | |||||

| 29 | Bültmann et al., (2009) [55] Denmark | Coordinated and Tailored Work Rehabilitation (CTWR) | Musculoskeletal disorders or LBP Subacute and chronic Sick listed | OP TH CH PSY PSY-C Team discussions about diagnosis and treatment plan PSY-C as caseworker establishing and maintaining contact with the workplace and the municipal case manager Report of a work rehabilitation plan to GP | CTWR: existing of Work disability screening 1×, 2 h, 4–12 w after sick leave Interdisciplinary Assessment Work rehabilitation plan max. 3 months Interdisciplinary with patient Assessment Workplace intervention |

| Non-randomized trial design | |||||

| 30 | Heijbel et al., (2013) [56] Sweden | Occupational Health Service (OHS) | Mixed group Musculoskeletal problems Subacute and chronic Sick listed | PH TH PSY NRS Team assessment | Team assessment With team Assessment Rehabilitation meeting and plan of measures With patient, supervisor, several OHS team members, local insurance office, trade union (optional) Treatment Education Cognitive-behavioral therapy 4 w, FU 6 m or 12 m Workplace intervention Follow-up meeting after rehabilitation |

| Between primary care and secondary or tertiary care and social care | |||||

| Randomized trial designs | |||||

| 31 | 1: Lambeek et al., (2007) [58] 2: Lambeek et al., (2010) [59] 3: Lambeek et al., (2010) [60] *Interventions are identical to the interventions of Steenstra and Anema. (number 32) The Netherlands | Multidisciplinary outpatient care program (MOC) | Non-specific LBP Chronic Sick listed <2 years | CM: coordination of care and communication team (primary-tertiary care) THs Patients own medical specialist GP OP Conference call with team: 1×/3 w | MOC existing of: Case management protocol CM collect information from HCP team. Referral in collaboration with OP. Organization of conference calls. Assessment Workplace intervention protocol 8 h, 4 w TH helps to achieve consensus between patient and supervisor for return to work Workplace intervention Graded activity program max. 26 sessions, max. 12 weeks Local TH practices Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| 32 | 1: Steenstra et al., (2003) [61] 2: Anema et al., (2007) [57] *Interventions are identical to the interventions of Lambeek. (number 31) The Netherlands | Workplace intervention and Graded Activity | Non-specific LBP Subacute and chronic Sick listed | 1: OP GP Contact about referral 2: OP GP THs Workplace intervention with worker, employer, OP, GP | Combined intervention (CI): existing of Workplace intervention (WI) direct after inclusion (2–6 weeks after sick leave), 24 d Assessment Workplace intervention Graded Activity Program (optional) 0.5 h, 2×/w, max. 26× After 8 weeks of sick leave By TH Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| Between primary care and community-based care | |||||

| Randomized trial designs and qualitative designs | |||||

| 33 | 1: McBeth et al., (2012) [66] 2: Bee et al., (2016) [62] England | Combined Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT) and prescribed exercise (PE) | Fibromyalgia Chronic | TH FI Two-way information exchange between TH and FI | T-CBT 1 h telephone assessment 30–45 min, 1×/w, 7 w, FU 3 and 6 m By TH Education—Knowledge of treatment Cognitive-behavioral therapy PE 20–60 h-2×/w By FI General exercise therapy |

| 34 | 1: Bennell et al., (2012) [64] 2: Hinman et al., (2015) [65] 3: Bennell et al., (2017) [63] Australia | Physiotherapy plus telephone coaching | Patients with knee OA Subacute and chronic | TH TC Written information exchange between the TC and TH occurred after each session. | Physical therapy program 30 m, 5×, 6 months Specific exercise therapy General exercise therapy Information booklet Education—Knowledge of disease prevention and ergonomics Telephone coaching 6–12×, 6 months Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| Author & Year | Study Date | Study Design & N | Study Outcomes | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In primary care | |||||

| Randomized trial designs | |||||

| 1 | Calner et al., | 2011–2014 | RCT | Health | |

| (2016) [49] | * Pain intensity (100-mm Visual Analogue Scale) | 4 m:-1 y: - | |||

| n = I:60, C:49 | * Pain-related disability (Pain Disability Index) | 4 m:-1 y: - | |||

| * Health-related quality of life (36-item Short-Form Health Survey) | All domains: 4 m:-1 y: - | ||||

| Costs | |||||

| * Work-related aspects and behavior § (Work Ability Index (7–49)) | 4 m:-1 y: - | ||||

| * Working percentage § | +/- | ||||

| 2 | Chelimsky et | - | Controlled pilot | Health | n.d between groups, over time: |

| al., (2013) [71] | study | * Pain intensity (0–10 Numeric Rating Scale) | 0 m-1 y: + | ||

| * Pain qualities (Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire) | 0 m-1 y: + | ||||

| n = 40 pt | * Physical functioning; measured with: | ||||

| n = I:12, C:16 | - Multidimensional Pain Inventory Interference Scale | 0 m-1 y: + | |||

| HCPs | - Brief Pain Inventory | 0 m-1 y: + | |||

| - Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale | 0 m-1 y: - | ||||

| HCPs are | * Emotional functioning; measured with: | ||||

| controlled, not | - Back Depression Inventory | 0 m-1 y: + | |||

| the pts | - Profile of Mood States | 0 m-1 y: + | |||

| Experienced quality of care by patients | |||||

| * Participant ratings of global improvement and satisfaction with treatment; | |||||

| measured with: | |||||

| - Patient Global Impression of Change | n.d. | ||||

| - Treatment helpfulness questionnaire | n.d. | ||||

| - Facilitation of patient involvement in care | + | ||||

| Satisfaction with work by HCPs | n.d between groups, over time: | ||||

| * Experiences with work ¥ (24-item physician perspectives questionnaire) | |||||

| - Knowledge | I: 0 m-1 y:- C: 0 m-1 y: - | ||||

| - Diagnosis/Management | I: 0 m-1 y: + C: 0 m-1 y: + | ||||

| - Treatment Comfort | I: 0 m-1 y:- C: 0 m-1 y: - | ||||

| - Treatment Satisfaction | I: 0 m-1 y: + C: 0 m-1 y: - | ||||

| - Use of Referrals | I: 0 m-1 y: + C: 0 m-1 y: - | ||||

| * Interview regarding: MD functional approach, Patient functional approach, | All: + | ||||

| Enabling self-management, Assessing patient mood, Assessing patient sleep, | |||||

| Comfort with use of medication | |||||

| 3 | DeBar et al., | 2014–2017 | Protocol | Health | n.a. |

| (2018) [77] | Randomized | * Pain, Enjoyment, General Activity (PEG) § (3-item measure based on Short Form | |||

| pragmatic trial | of the Brief Pain Inventory) | ||||

| * Pain-related disability (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire) | |||||

| Intended n = 851 | |||||

| pt in clusters | Costs | ||||

| * Healthcare utilization (opioids dispensed, both aggregated and disaggregated | |||||

| primary care contact, use of specialty pain services, inpatient services related to | |||||

| pain, and overall outpatient utilization) | |||||

| Experienced quality of care by patients | |||||