22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome as a Human Model for Idiopathic Scoliosis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

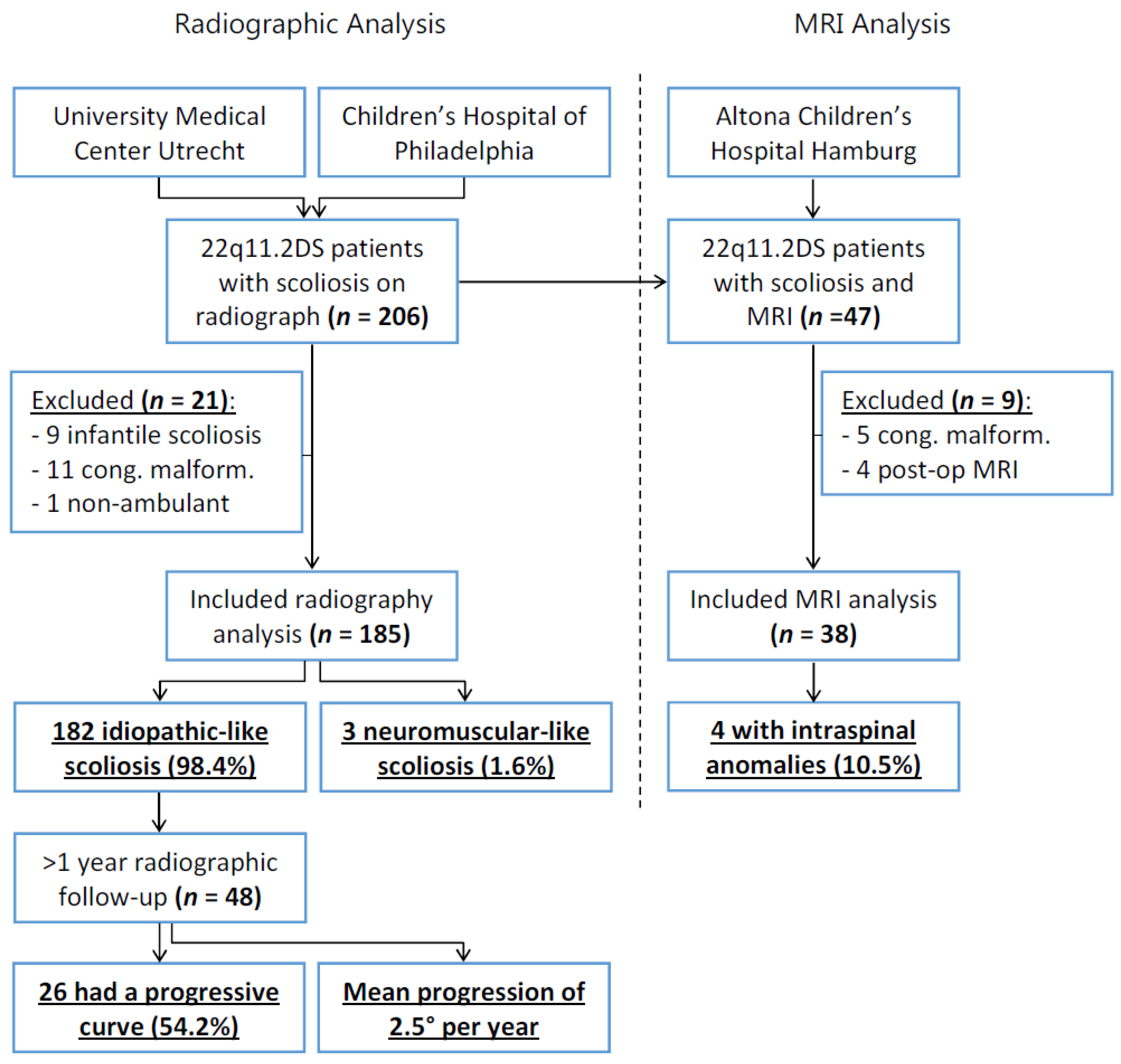

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Radiographic Analysis

2.3. MRI Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

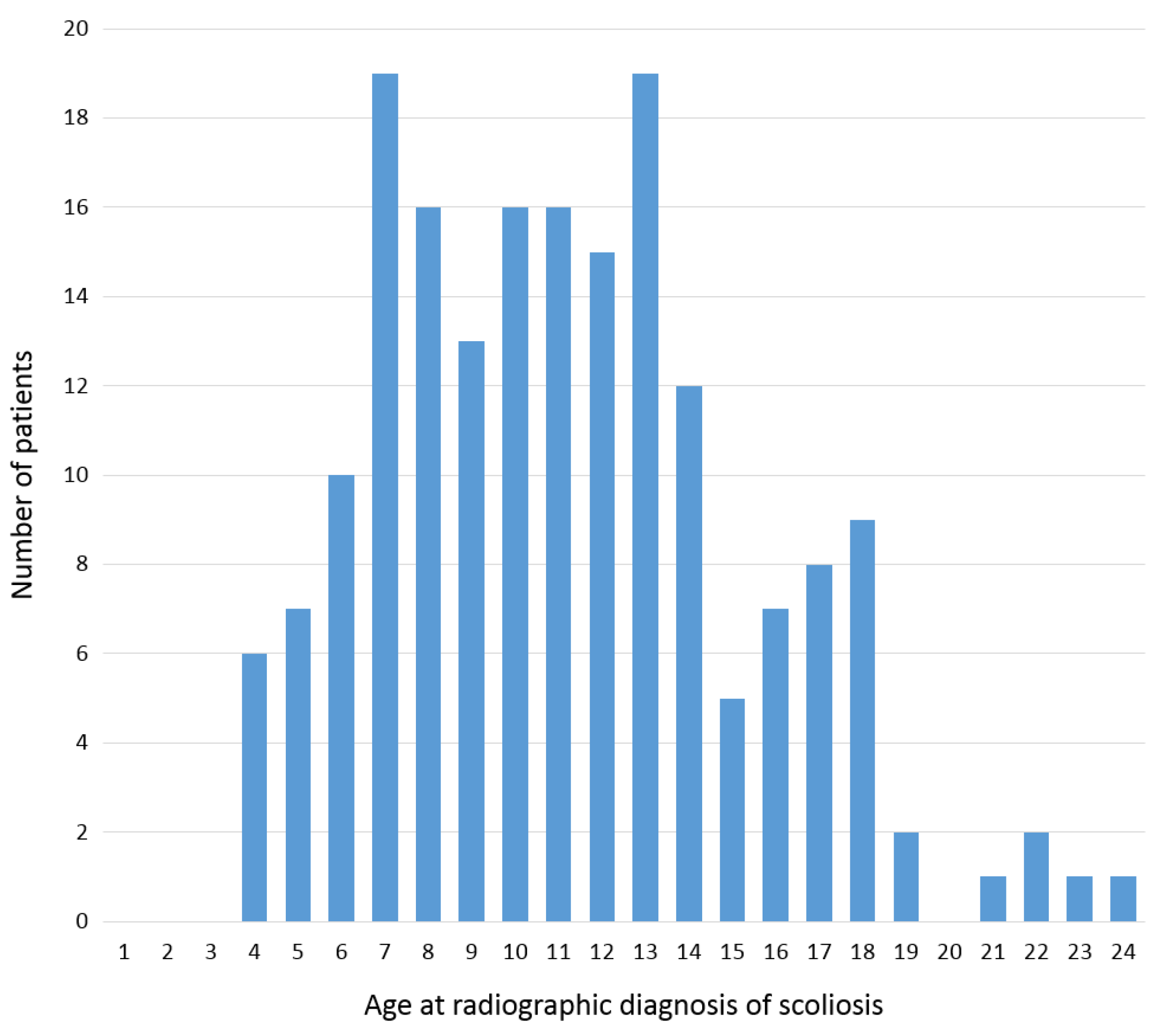

3.1. Study Population

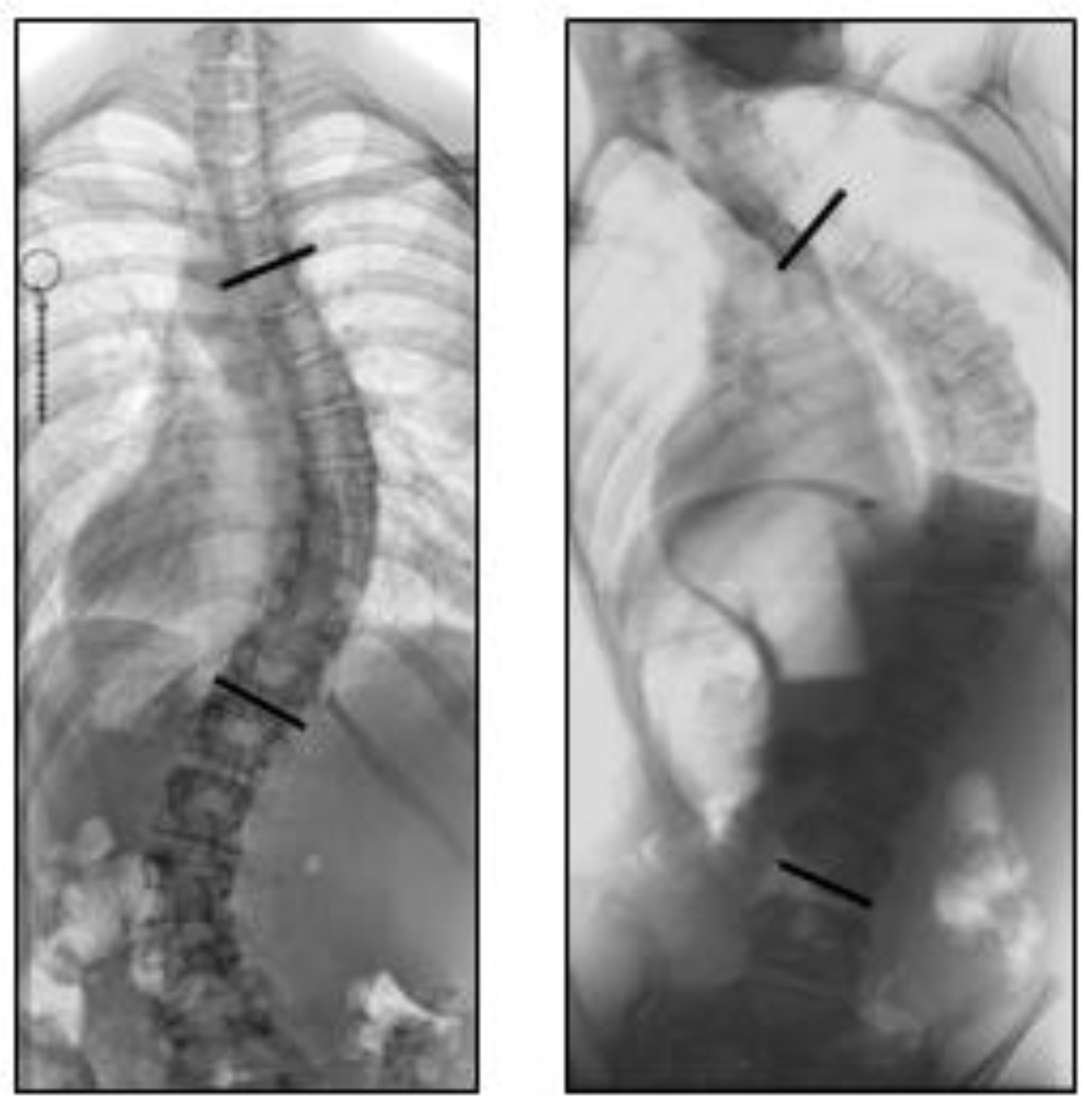

3.2. Radiographic Analysis

3.3. MRI Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, J.C.; Castelein, R.M.; Chu, W.C.; Danielsson, A.J.; Dobbs, M.B.; Grivas, T.B.; Gurnett, C.A.; Luk, K.D.; Moreau, A.; Newton, P.O.; et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015, 1, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kouwenhoven, J.-W.M.; Castelein, R.M. The pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Review of the literature. Spine 2008, 33, 2898–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlösser, T.P.C.; van der Heijden, G.J.M.G.; Versteeg, A.L.; Castelein, R.M. How “idiopathic” is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? A systematic review on associated abnormalities. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorman, K.F.; Julien, C.; Moreau, A. The genetic epidemiology of idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2012, 21, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kesling, K.L.; Reinker, K.A. Scoliosis in twins: A meta-analysis of the literature and report of six cases. Spine 1997, 22, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouwenhoven, J.W.; Smit, T.H.; van der Veen, A.J.; Kingma, I.; van Dieen, J.H.; Castelein, R.M. Effects of dorsal versus ventral shear loads on the rotational stability of the thoracic spine: A biomechanical porcine and human cadaveric study. Spine 2007, 32, 2545–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castelein, R.M.; Pasha, S.; Cheng, J.C.Y.C.; Dubousset, J. Idiopathic Scoliosis as a Rotatory Decompensation of the Spine. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 1850–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasha, S.; de Reuver, S.; Homans, J.F.; Castelein, R.M. Sagittal curvature of the spine as a predictor of the pediatric spinal deformity development. Spine Deform. 2021, 9, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.M.A.; de Wilde, R.F.; Kouwenhoven, J.-W.M.; Castelein, R.M. Experimental animal models in scoliosis research: A review of the literature. Spine J. 2011, 11, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boswell, C.W.; Ciruna, B. Understanding Idiopathic Scoliosis: A New Zebrafish School of Thought. Trends Genet. 2017, 33, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, M.; Dubousset, J.; Imamura, Y.; Iwaya, T.; Yamada, T.; Kimura, J. An experimental study in chickens for the pathogenesis of idiopathic scoliosis. Spine 1993, 18, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobyn, J.D.; Little, D.G.; Gray, R.; Schindeler, A. Animal models of scoliosis. J. Orthop. Res. 2015, 33, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur, R.E.; Bassett, A.S.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Bearden, C.E.; Chow, E.; Emanuel, B.S.; Owen, M.; Swillen, A.; Van den Bree, M.; Vermeesch, J.; et al. A neurogenetic model for the study of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: The International 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome Brain Behavior Consortium. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Sullivan, K.E.; Marino, B.; Philip, N.; Swillen, A.; Vorstman, J.A.S.; Zackai, E.H.; Emanuel, B.S.; Vermeesch, J.R.; Morrow, B.E.; et al. 22Q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grati, F.R.; Molina Gomes, D.; Ferreira, J.C.P.B.; Dupont, C.; Alesi, V.; Gouas, L.; Horelli-Kuitunen, N.; Choy, K.W.; García-Herrero, S.; de la Vega, A.G.; et al. Prevalence of recurrent pathogenic microdeletions and microduplications in over 9500 pregnancies. Prenat. Diagn. 2015, 35, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojevic, C.; Heung, T.; Theriault, M.; Tomita-Mitchell, A.; Chakraborty, P.; Kernohan, K.; Bulman, D.E.; Bassett, A.S. Estimate of the contemporary live-birth prevalence of recurrent 22q11.2 deletions: A cross-sectional analysis from population-based newborn screening. Can. Med Assoc. Open Access J. 2021, 9, E802–E809. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, J.F.; Baldew, V.G.M.; Brink, R.C.; Kruyt, M.C.; Schlösser, T.P.C.; Houben, M.L.; Deeney, V.F.X.; Crowley, T.B.; Castelein, R.M.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M. Scoliosis in association with the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: An observational study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, J.F.; de Reuver, S.; Breetvelt, E.J.; Vorstman, J.A.S.; Deeney, V.F.X.; Flynn, J.M.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Kruyt, M.C.; Castelein, R.M. The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome as a model for idiopathic scoliosis—A hypothesis. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 127, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, I.M.; Sheppard, S.E.; Crowley, T.B.; McGinn, D.E.; Bailey, A.; McGinn, M.J.; Unolt, M.; Homans, J.F.; Chen, E.Y.; Salmons, H.I.; et al. What is new with 22q? An update from the 22q and You Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part. A 2018, 176, 2058–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, A.S.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Devriendt, K.; Digilio, M.C.; Goldenberg, P.; Habel, A.; Marino, B.; Oskarsdottir, S.; Philip, N.; Sullivan, K.; et al. Practical Guidelines for Managing Patients with 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Kulklo, T.; Blanke, K.; Lenke, L. Spinal Deformity Study Group Radiographic Measurement Manual; Medtronic Sofamor Danek USA, Inc.: Memphis, TN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, M.J.; Ohtsuka, K. The natural history of congenital scoliosis. A study of two hundred and fifty-one patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1982, 64, 1128–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abul-Kasim, K.; Ohlin, A. Curve Length, Curve Form, and Location of Lower-End Vertebra as a Means of Identifying the Type of Scoliosis. J. Orthop. Surg. 2010, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Felice, F.; Zaina, F.; Donzelli, S.; Negrini, S. The Natural History of Idiopathic Scoliosis during Growth: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 97, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heemskerk, J.L.; Kruyt, M.C.; Colo, D.; Castelein, R.M.; Kempen, D.H.R. Prevalence and risk factors for neural axis anomalies in idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review. Spine J. 2018, 18, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, S.; Chae, H.-W.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, S.; Kwon, J.-W.; Lee, S.-B.; Moon, S.-H.; Lee, H.-M.; Lee, B.H. Incidence and Surgery Rate of Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Nationwide Database Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strahle, J.; Smith, B.W.; Martinez, M.; Bapuraj, J.R.; Muraszko, K.M.; Garton, H.J.L.; Maher, C.O. The association between Chiari malformation Type I, spinal syrinx, and scoliosis. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2015, 15, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yılmaz, H.; Zateri, C.; Kusvuran Ozkan, A.; Kayalar, G.; Berk, H. Prevalence of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Turkey: An epidemiological study. Spine J. 2020, 20, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, H.A.; Moe, J.H.; Bradford, D.S.; Winter, R.B. The selection of fusion levels in thoracic idiopathic scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 1983, 65, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenke, L.G.; Betz, R.R.; Harms, J.; Bridwell, K.H.; Clements, D.H.; Lowe, T.G.; Blanke, K. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis. J. Bone Jt. Surg.-Ser. A 2001, 83, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlösser, T.P.C.; Shah, S.A.; Reichard, S.J.; Rogers, K.; Vincken, K.L.; Castelein, R.M. Differences in early sagittal plane alignment between thoracic and lumbar adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2014, 14, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sullivan, T.B.; Reighard, F.G.; Osborn, E.J.; Parvaresh, K.C.; Newton, P.O. Thoracic Idiopathic Scoliosis Severity Is Highly Correlated with 3D Measures of Thoracic Kyphosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2017, 99, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonstein, J.; Carlson, J. The prediction of curve progression in untreated idiopathic scoliosis during growth Untreated of Curve Scoliosis in Growth. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1984, 66, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Homans, J.F.; Tromp, I.N.; Colo, D.; Schlösser, T.P.C.; Kruyt, M.C.; Deeney, V.F.X.; Crowley, T.B.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Castelein, R.M. Orthopaedic manifestations within the 22q11.2 Deletion syndrome: A systematic review. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part. A 2018, 176, 2104–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagi, S.; Lapi, E.; Gambineri, E.; Salti, R.; Genuardi, M.; Colarusso, G.; Conti, C.; Jenuso, R.; Chiarelli, F.; Azzari, C.; et al. Thyroid function and morphology in subjects with microdeletion of chromosome 22q11 (del(22)(q11)). Clin. Endocrinol. 2010, 72, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.C.; Qin, L.; Cheung, C.S.; Sher, A.H.; Lee, K.M.; Ng, S.W.; Guo, X. Generalized low areal and volumetric bone mineral density in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2000, 15, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.D.; Harding, A.F.; Morgan, E.L.; Nicholson, R.J.; Thomas, K.A.; Whitecloud, T.S.; Ratner, E.S. Trabecular bone mineral density in idiopathic scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1987, 7, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Ali, M.; Al-Othman, A.; Bubshait, D.; Al-Dakheel, D. Does scoliosis causes low bone mass? A comparative study between siblings. Eur. Spine J. 2008, 17, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burner, W.L.; Badger, V.M.; Sherman, F.C. Osteoporosis and acquired back deformities. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1982, 2, 383–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beals, R.K.; Haglund Kenny, K.; Lees, M.H. Congenital heart disease and idiopathic scoliosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1972, 89, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.E.; White, R.I.; Fischer, K.C.; Neill, C.; Dorst, J.P. The scoliosis of congenital heart disease. Am. Heart J. 1972, 84, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, J.F.; de Reuver, S.; Heung, T.; Silversides, C.K.; Oechslin, E.N.; Houben, M.L.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Kruyt, M.C.; Castelein, R.M.; Bassett, A.S. The role of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in the relationship between congenital heart disease and scoliosis. Spine J. 2020, 20, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirwald, R.L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Bailey, D.A.; Beunen, G.P. An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Homans, J.F.; Schlosser, T.P.C.; Pasha, S.; Kruyt, M.; Castelein, R. Variations in the sagittal spinal profile precede the development of scoliosis: A pilot study of a new approach. Spine J. 2021, 21, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Current Study | Abul-Kasim et al. (2010) 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 22q11.2DS | Idiopathic Scoliosis | Neuro. Scoliosis | |

| n | 185 | 77 | 21 |

| Major curve location | |||

| - Thoracic | 79 (43%) | 52 (68%) | 5 (24%) |

| - Thoracolumbar | 54 (29%) | 13 (17%) | 12 (57%) |

| - Lumbar | 52 (28%) | 12 (16%) | 4 (19%) |

| Median curve length in № vertebrae (IQR) | 6 (5–7) | 7 (7–8) | 10 (9–11) |

| >8 vertebrae in curve | 18 (10%) | 3 (4%) | 19 (90%) |

| Curve morphology | |||

| - S-shape | 127 (69%) | 14 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| - C-shape | 58 (31%) | 63 (82%) | 21 (100%) |

| Lower-end vertebra | |||

| - L3+ | 114 (62%) | 62 (81%) | 5 (24%) |

| - L4 | 67 (36%) | 15 (19%) | 8 (38%) |

| - L5 | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (38%) |

| Fulfilled criteria for 2 | |||

| - Neuro. scoliosis | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (76%) |

| - Idiopathic scoliosis | 183 (98%) | 77 (100%) | 5 (24%) |

| Current Study | Heemskerk et al. (2018) 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| 22q11.2DS | Idiopathic Scoliosis | |

| n | 38 | 8622 |

| Spinal anomaly: | ||

| -Isolated syrinx | 318 (3.7%) | |

| -Isolated Arnold-Chiari malf. | 259 (3.0%) | |

| -Arnold-Chiari malf. with syrinx | 218 (2.5%) | |

| -Tethered cord | 49 (0.57%) | |

| -Dural ectasia | 33 (0.38%) | |

| -Cerabral or intra/paraspinal tumors | 22 (0.26%) | |

| -Tonsilar herniation | 1 (3%) | 20 (0.23%) |

| -Diastematomyelia | 19 (0.22%) | |

| -Abnormal position of conus | 10 (0.12%) | |

| -Extra- or intradural cysts | 1 (3%) | 6 (0.07%) |

| -Intraspinal lipoma | 1 (3%) | 5 (0.06%) |

| -Discopathy | 4 (0.05%) | |

| -Hydrocephalus | 3 (0.03%) | |

| -Vertebral body abnormality | 2 (5%) 2 | 3 (0.03%)3 |

| -Hydromyelia | 2 (0.02%) | |

| -Craniocervical junctional narrowing | 1 (0.01%) | |

| -Cerebellar angioma | 1 (0.01%) | |

| -Dandy-Walker syndrome | 1 (0.01%) | |

| -Arteriovenous fistula | 1 (0.01%) | |

| -Not specified | 88 (1%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Reuver, S.; Homans, J.F.; Schlösser, T.P.C.; Houben, M.L.; Deeney, V.F.X.; Crowley, T.B.; Stücker, R.; Pasha, S.; Kruyt, M.C.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; et al. 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome as a Human Model for Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214823

de Reuver S, Homans JF, Schlösser TPC, Houben ML, Deeney VFX, Crowley TB, Stücker R, Pasha S, Kruyt MC, McDonald-McGinn DM, et al. 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome as a Human Model for Idiopathic Scoliosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(21):4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214823

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Reuver, Steven, Jelle F. Homans, Tom P. C. Schlösser, Michiel L. Houben, Vincent F. X. Deeney, Terrence B. Crowley, Ralf Stücker, Saba Pasha, Moyo C. Kruyt, Donna M. McDonald-McGinn, and et al. 2021. "22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome as a Human Model for Idiopathic Scoliosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 21: 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214823

APA Stylede Reuver, S., Homans, J. F., Schlösser, T. P. C., Houben, M. L., Deeney, V. F. X., Crowley, T. B., Stücker, R., Pasha, S., Kruyt, M. C., McDonald-McGinn, D. M., & Castelein, R. M. (2021). 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome as a Human Model for Idiopathic Scoliosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(21), 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214823