Investigation of the Effect of Alkyl Chain Length on the Size and Distribution of Thiol-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Applications

Abstract

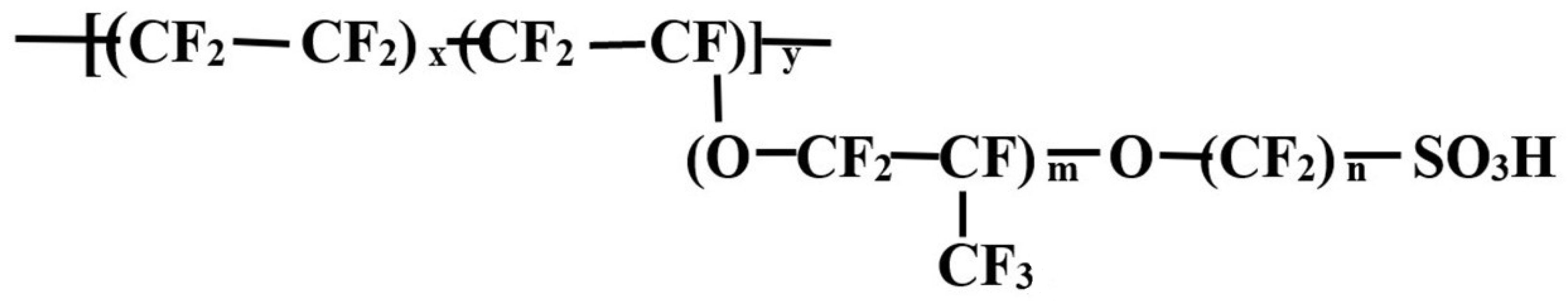

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

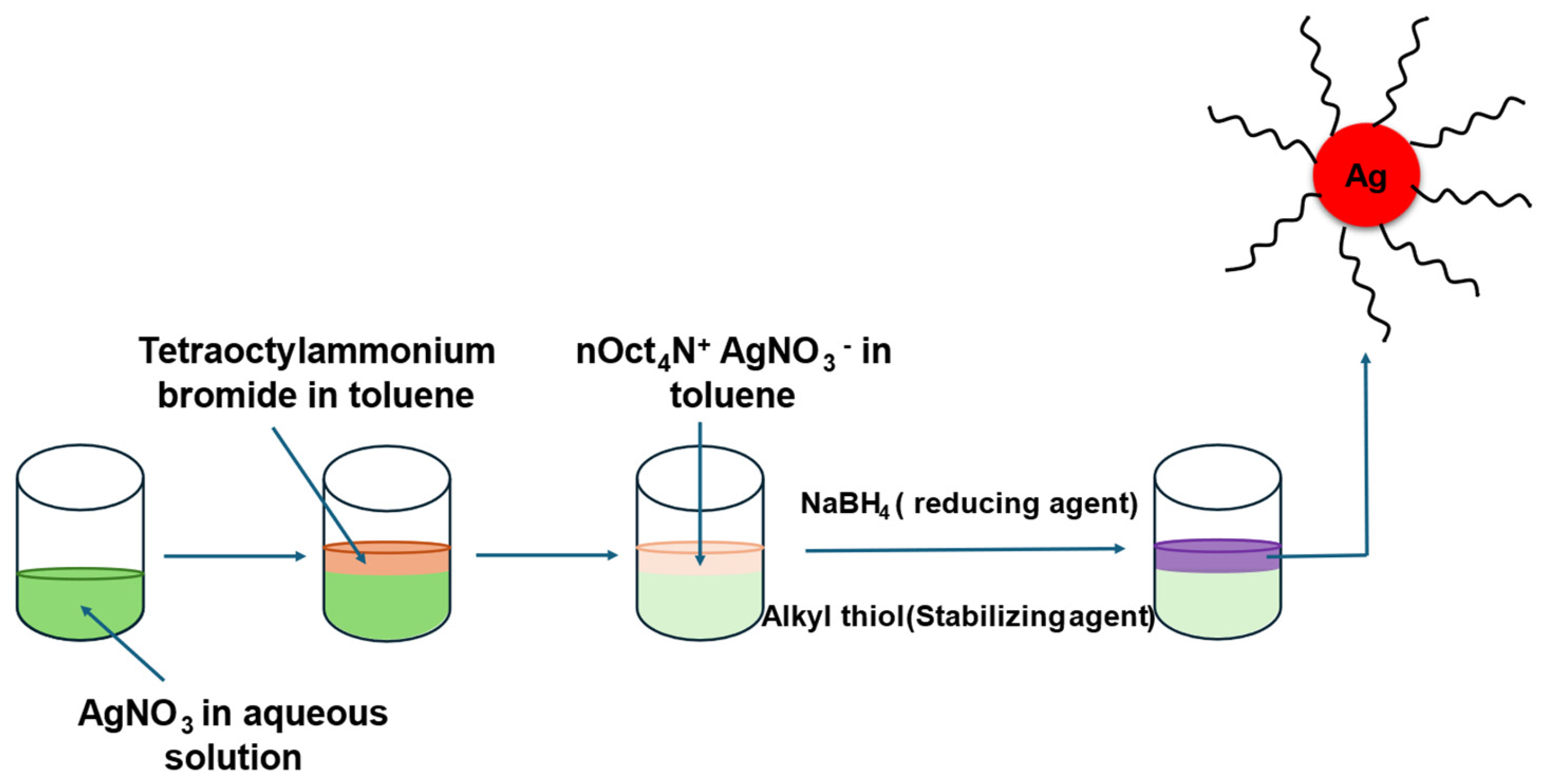

2.2. Fabrication of Ag NPs

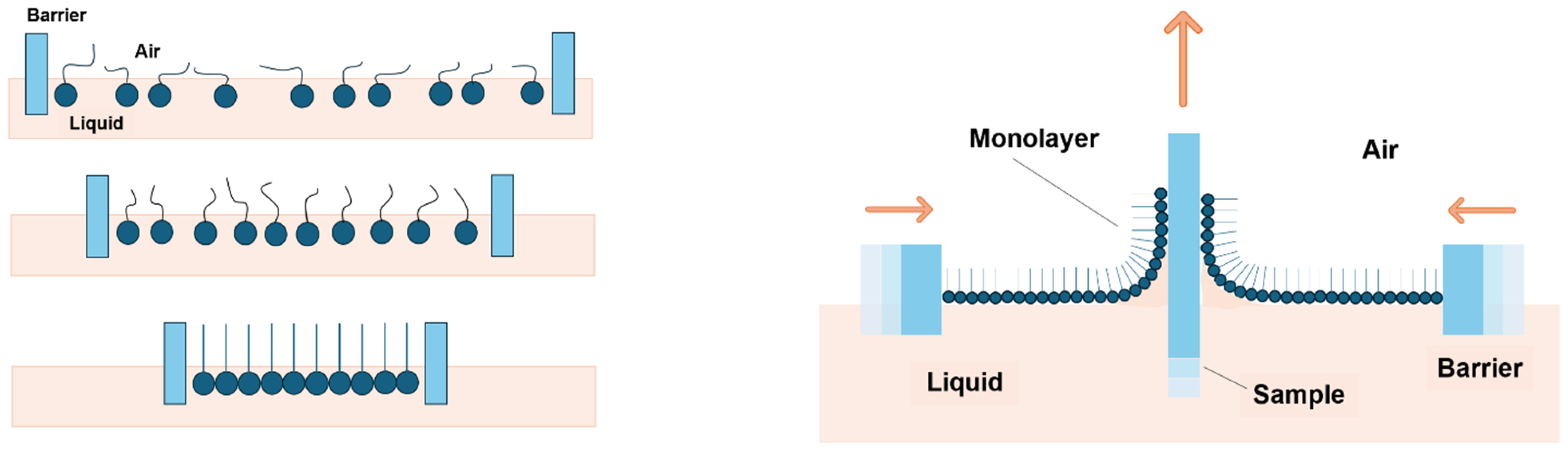

2.3. Deposition of Ag NPs

2.4. Crystal Structure and Morphology Study of Ag NPs

2.5. PEMFC Demonstration Kit Performance

2.6. High-Power PEMFC Performance Test

2.7. CO Tolerance Testing for Ag-Modified Catalysts

2.8. Durability Study

3. Results and Discussion

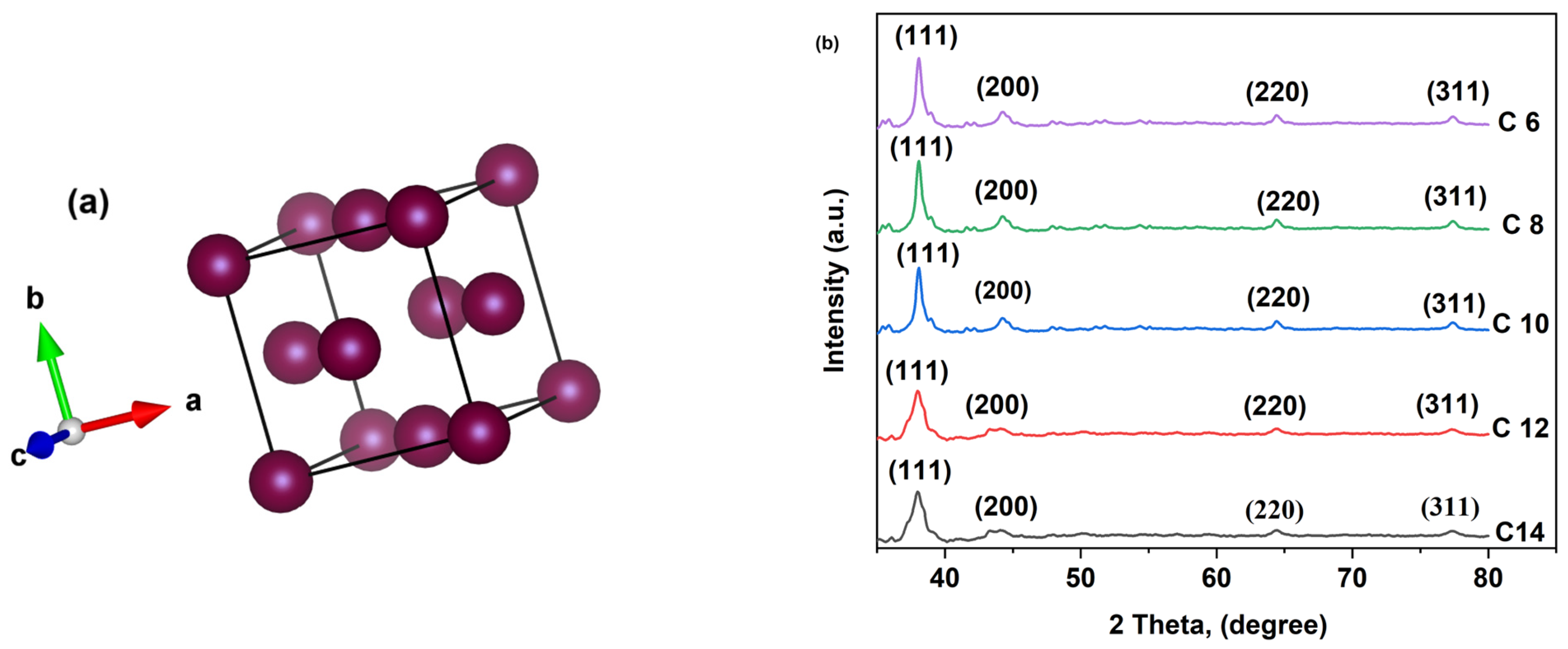

3.1. XRD Analysis

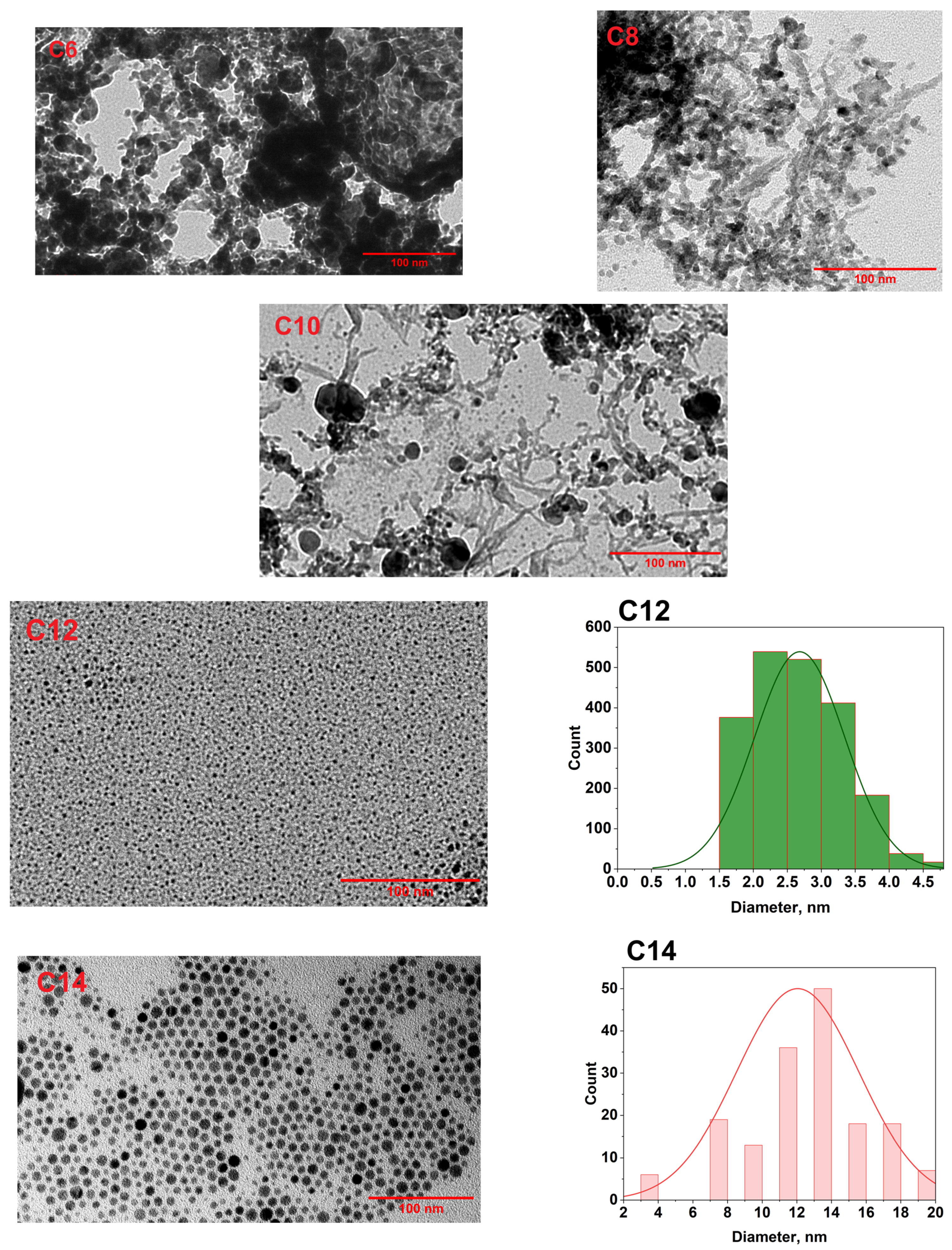

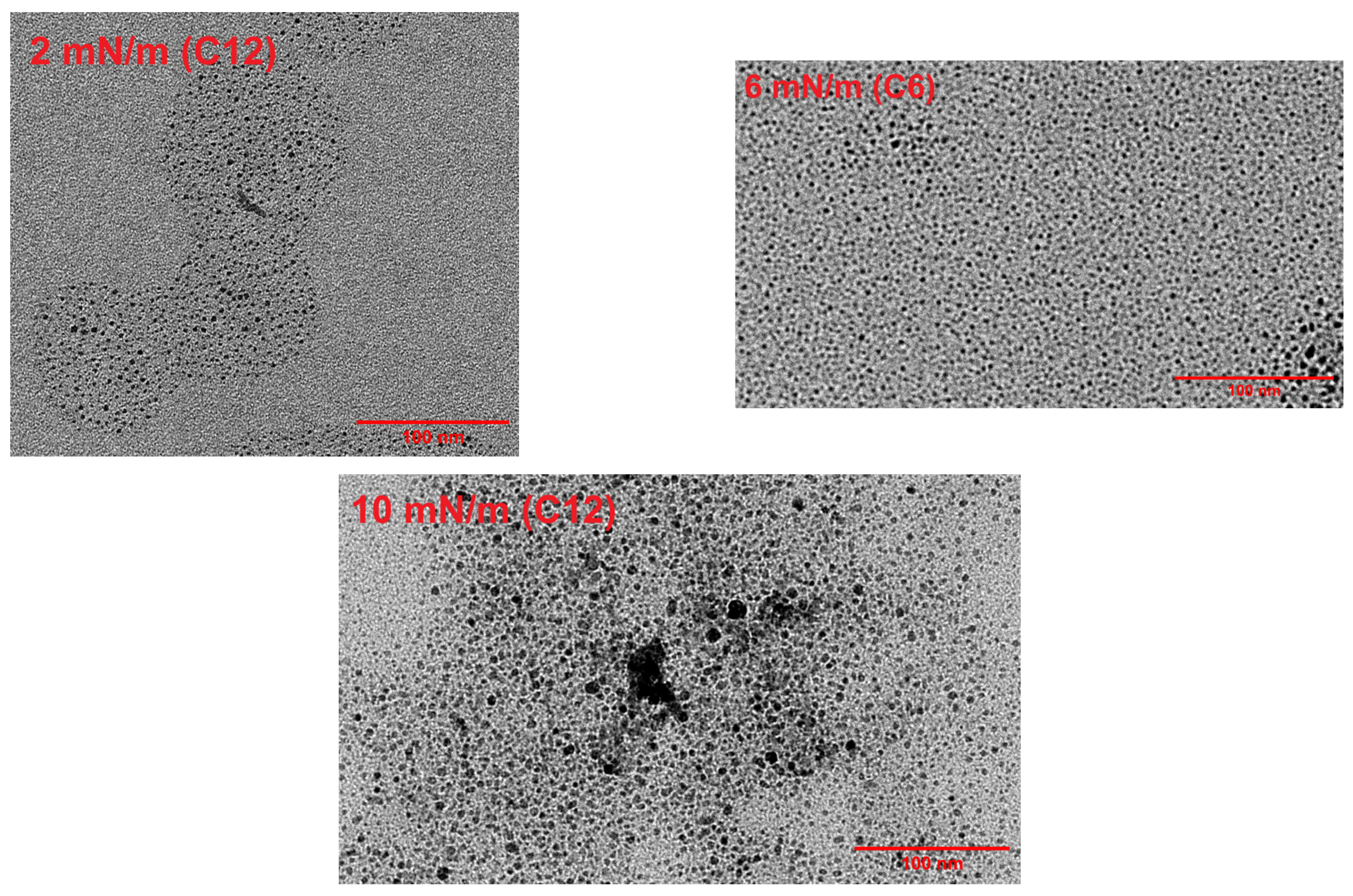

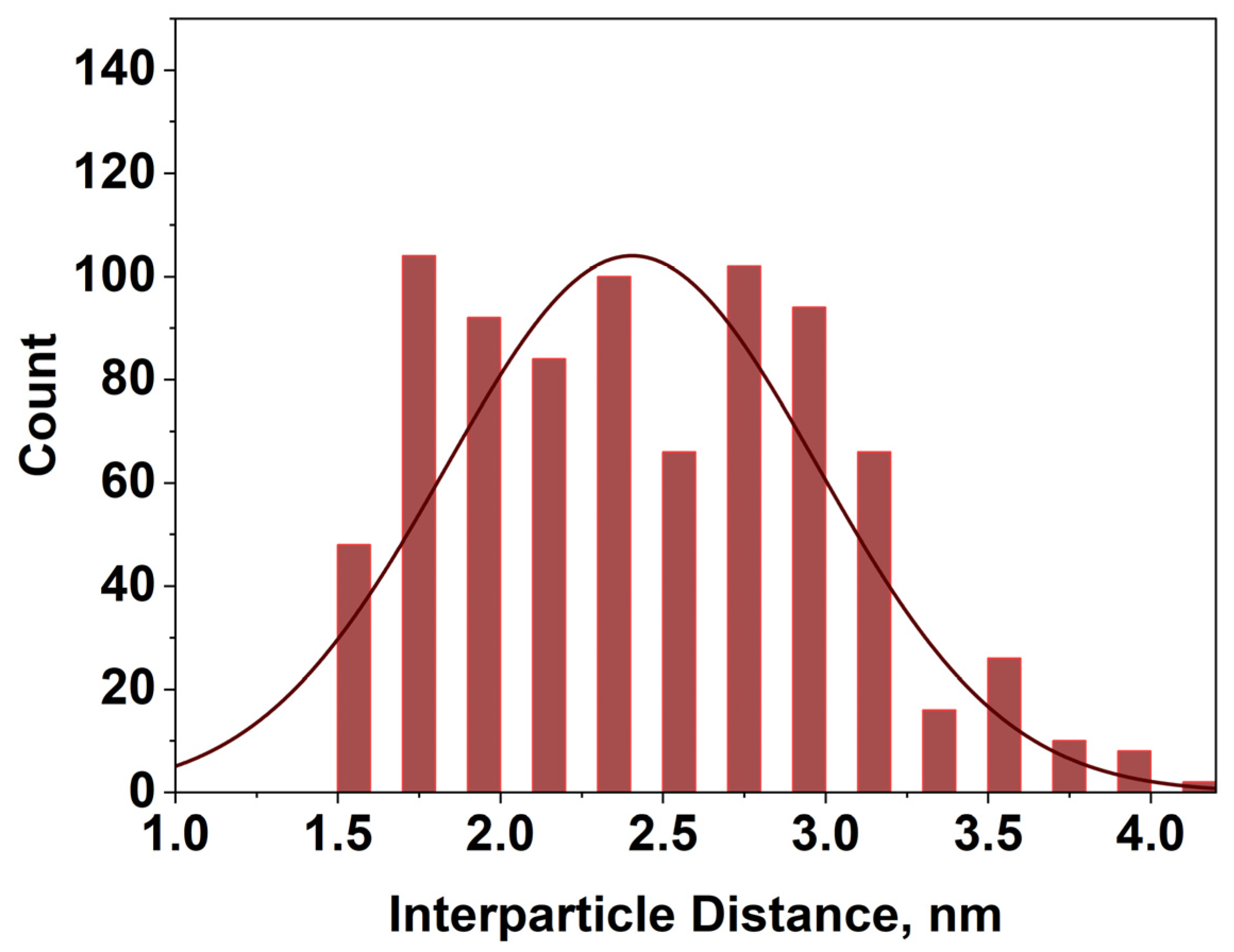

3.2. Morphology Study of Ag NPs by TEM

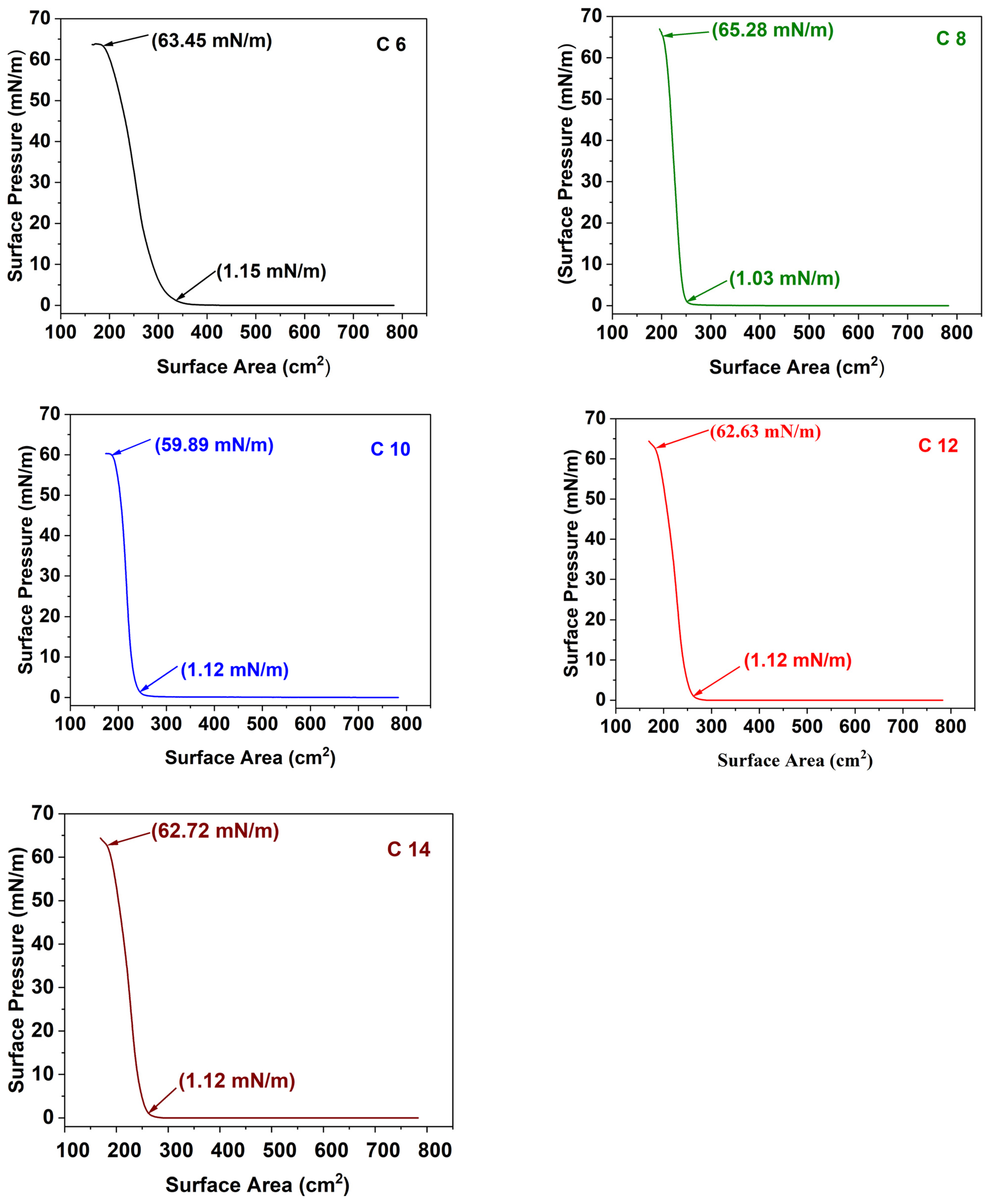

3.3. Ag NP Film Development

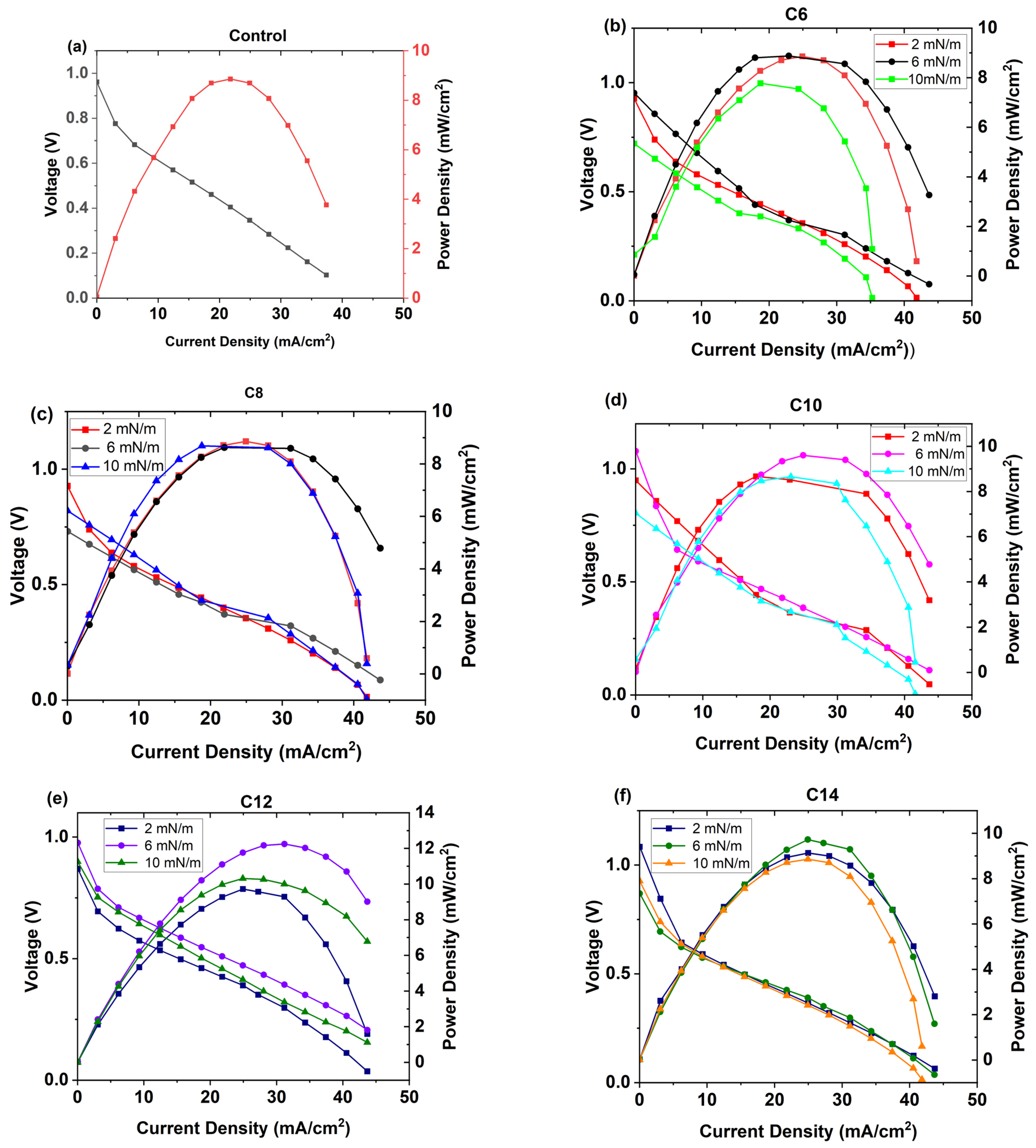

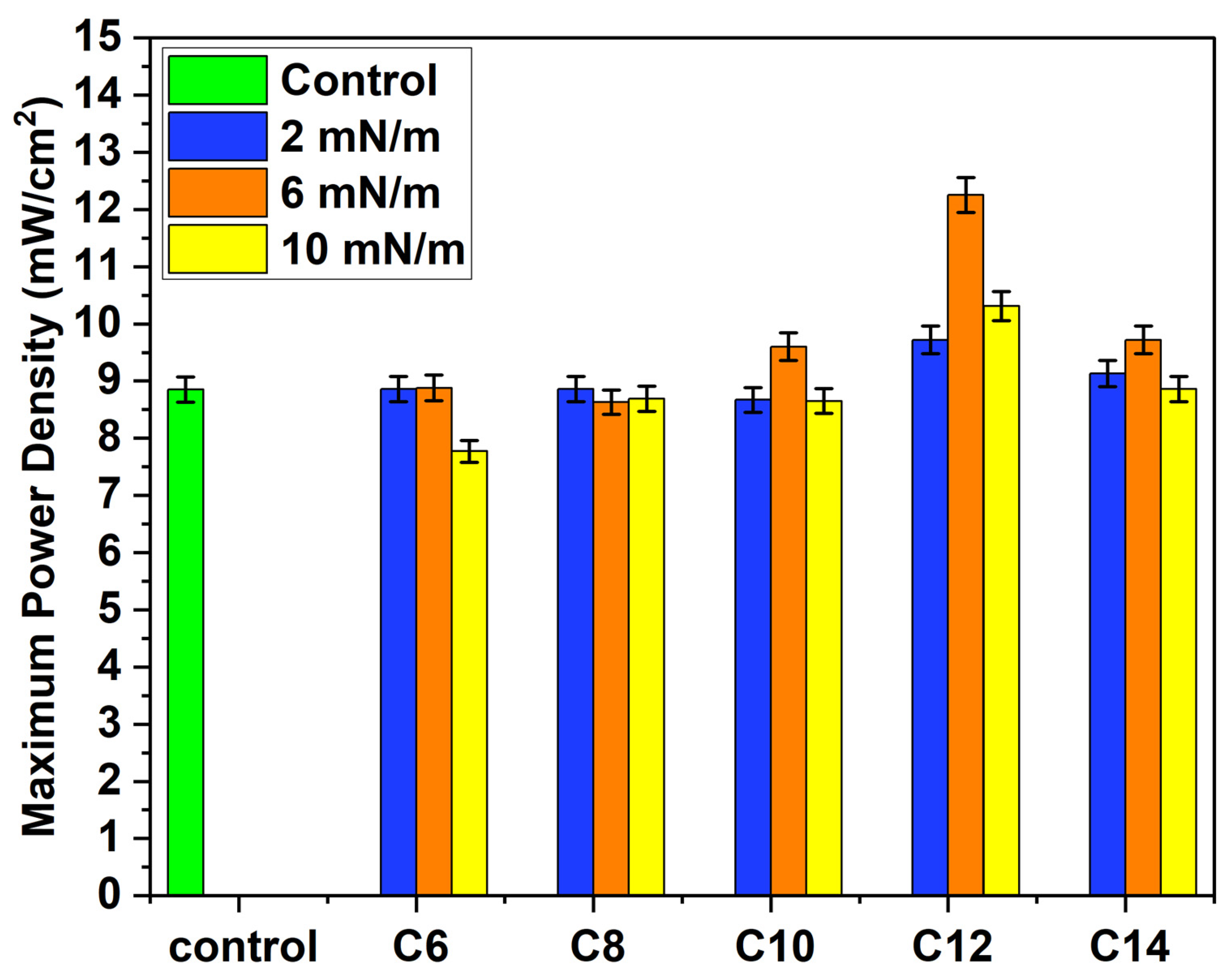

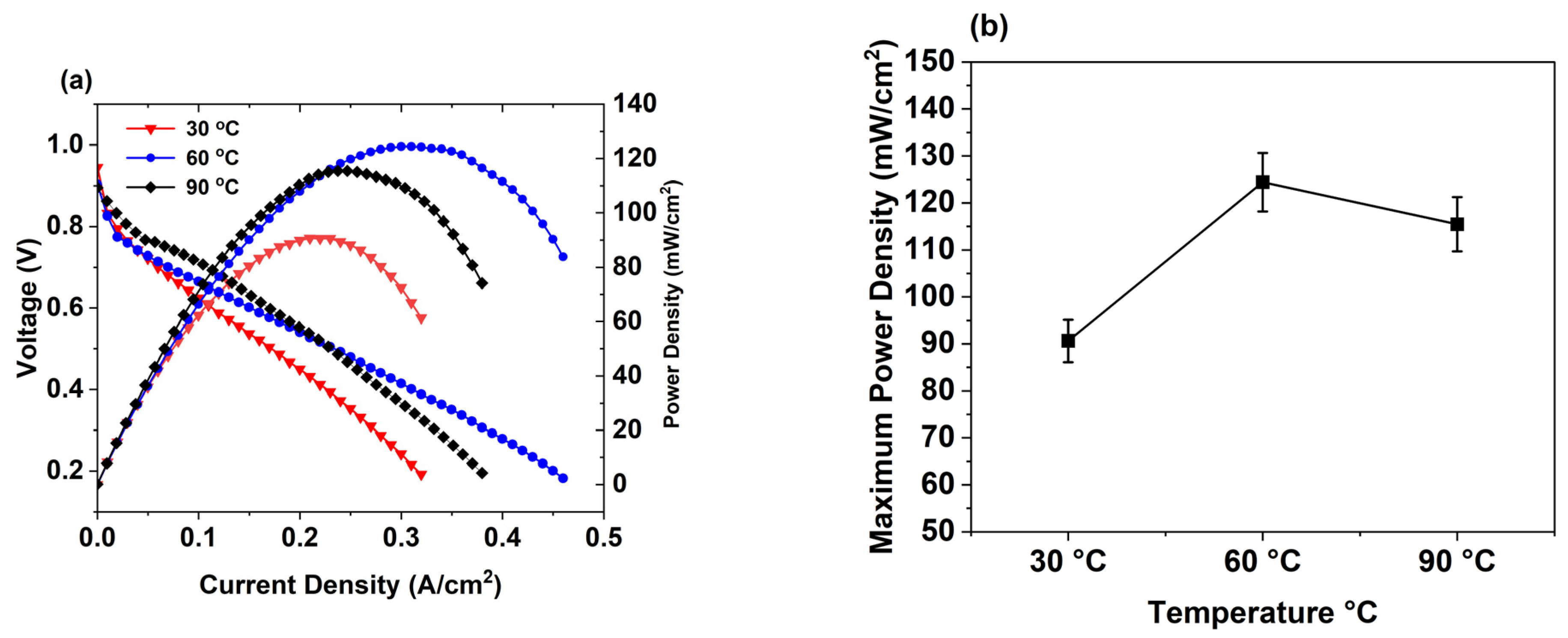

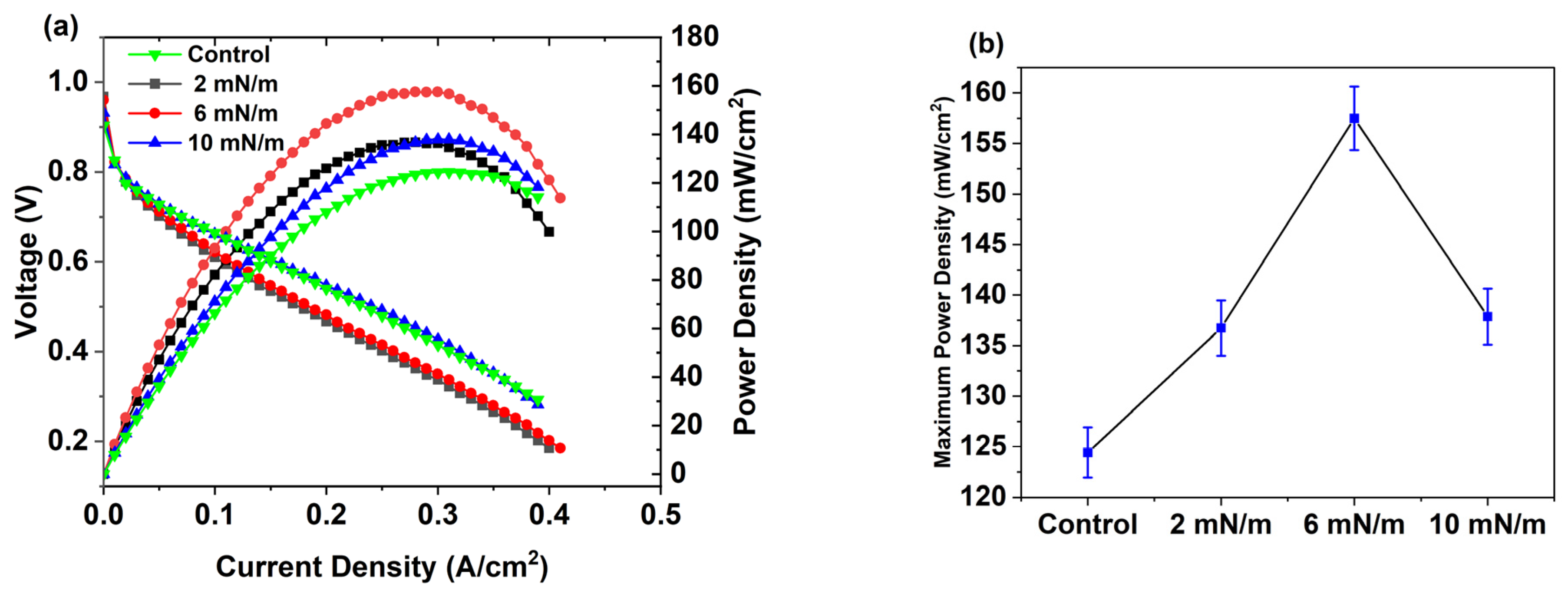

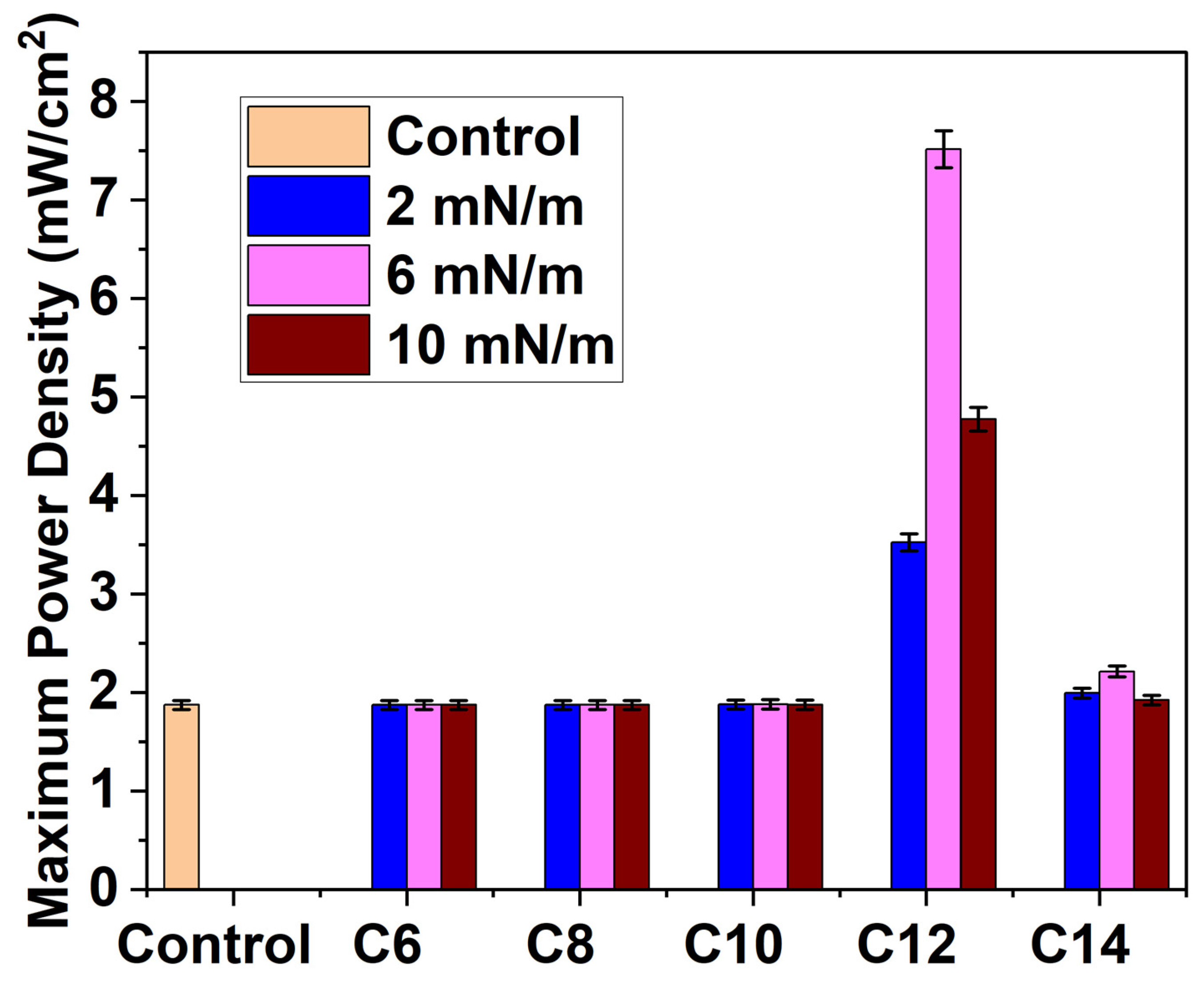

3.4. PEMFC Performance Test

3.5. CO Resistance Test

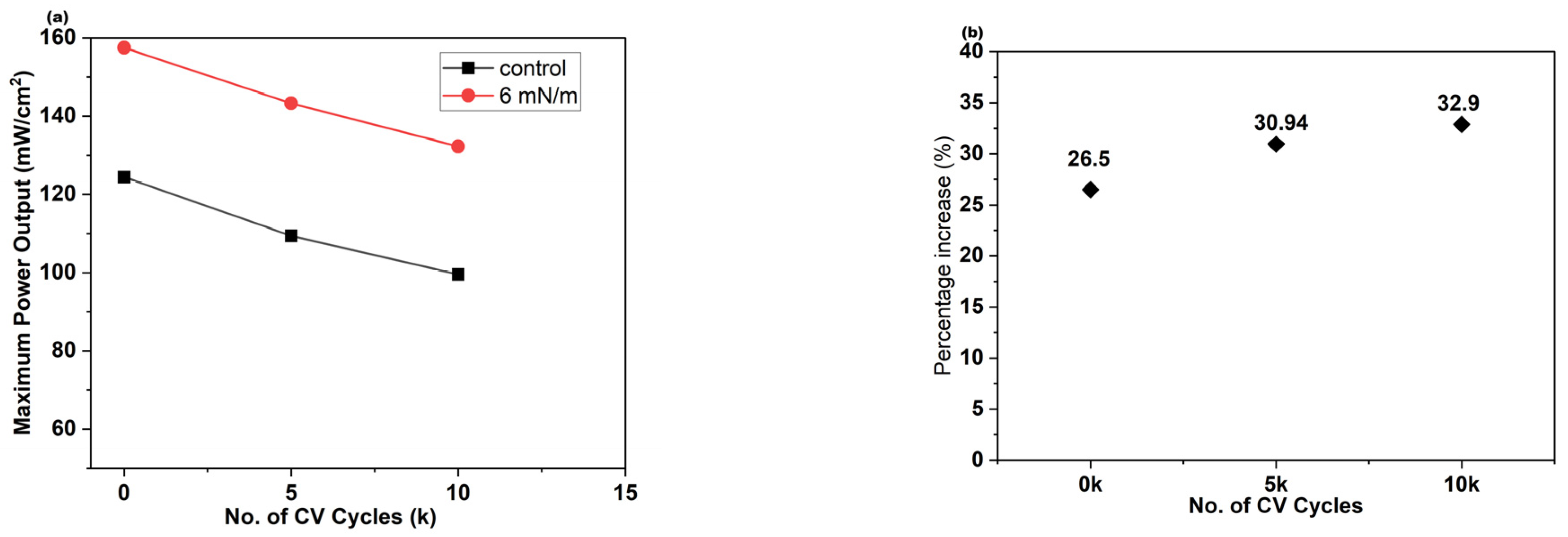

3.6. Durability Study

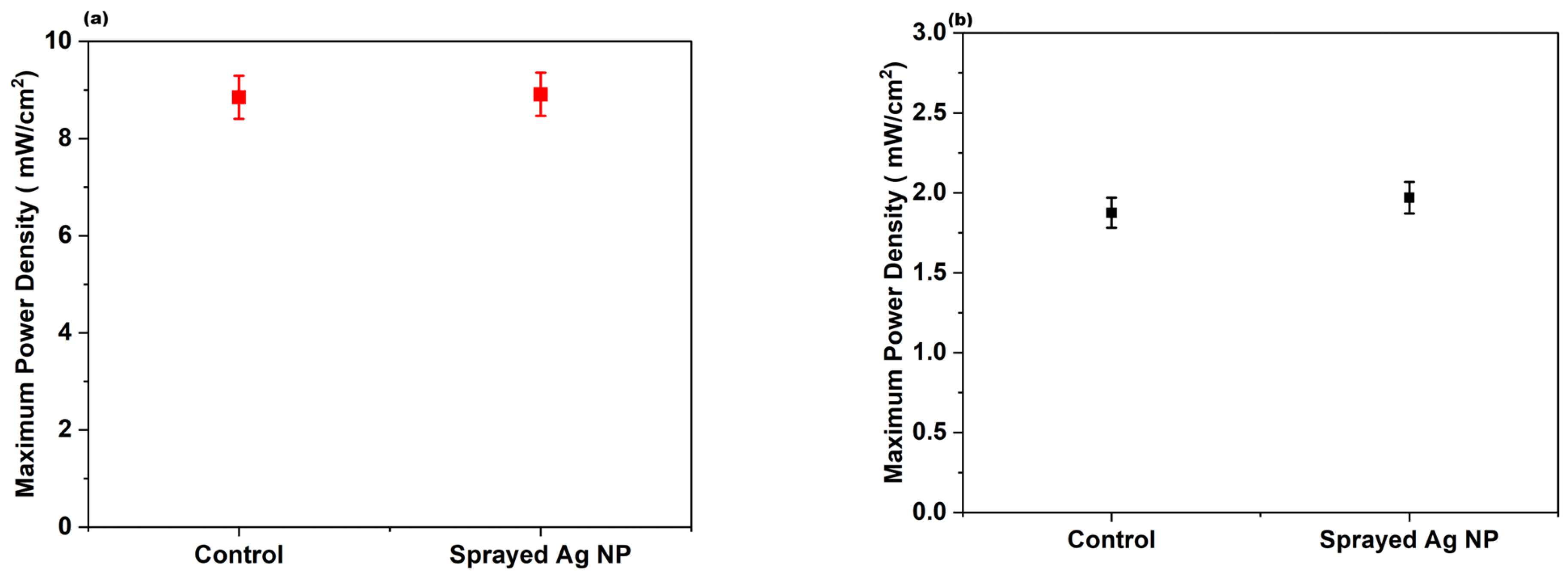

3.7. Performance and CO Resistance Test of C12 Ag NPs Coated by the Spray Method

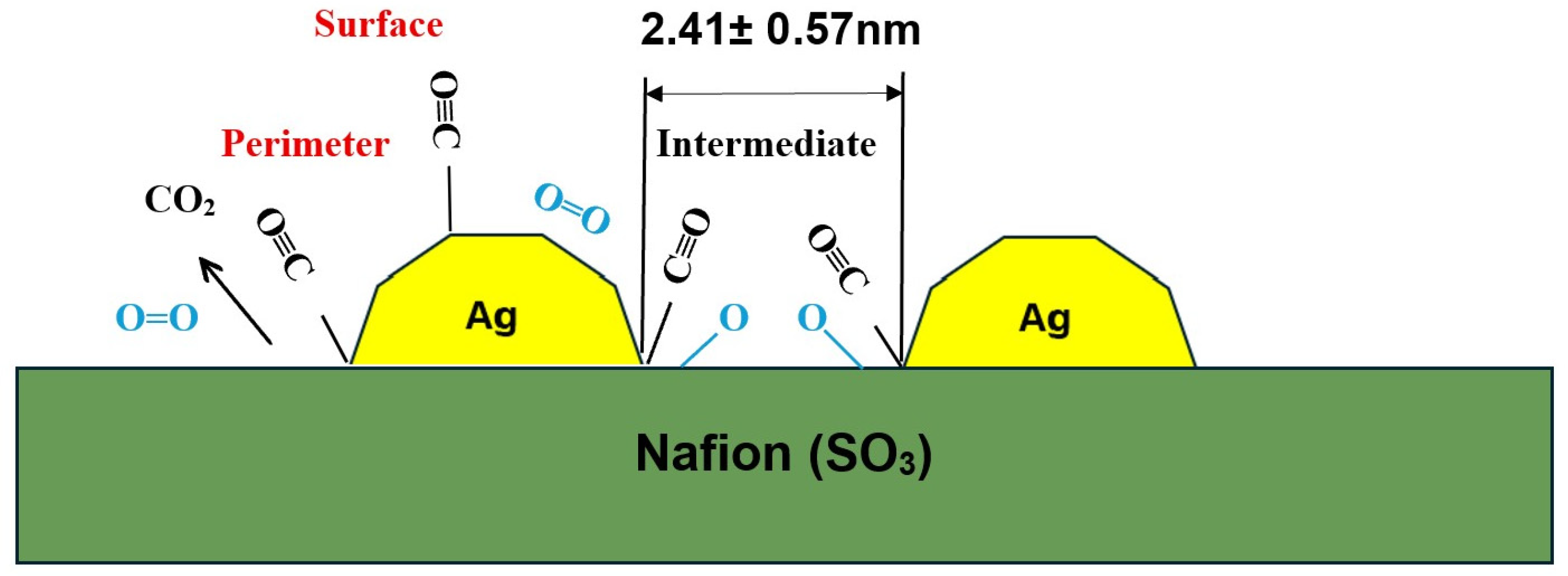

3.8. Catalytic Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kiani, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, R. Proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Recent developments and future perspectives. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 9392–9411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Yang, J.; Weng, Z.; Ma, F.; Liang, F.; Zhang, C. Review on proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Safety analysis and fault diagnosis. J. Power Sources 2024, 617, 235118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, A. Recent developments of proton exchange membranes for PEMFC: A review. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 956132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, M.; Tolj, I.; Barbir, F. Review of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell-Powered Systems for Stationary Applications Using Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2024, 17, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, A.; Fang, H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Rahman, M.F.; Fu, S.; Yin, Y.; Fang, Y.; Sprouster, D.; Isseroff, R.; Sharma, S.K.; et al. Designing a micro-cellulose membrane for hydrogen fuel cells. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 3025–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, H.; Akın, Y. Recent studies on proton exchange membrane fuel cell components, review of the literature. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 304, 118244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Song, W.; Wei, T.; Zhang, K.; Shao, Z. Improved CO tolerance of Pt nanoparticles on polyaniline-modified carbon for PEMFC anode. Fuel 2025, 382, 133239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, P.C. Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Catalyst Layer Degradation Mechanisms: A Succinct Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Tong, Y.; Hung, Y.M.; Wang, X. Progress on the durability of catalyst layer interfaces in proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 192, 358–377. [Google Scholar]

- Le Canut, J.-M.; Abouatallah, R.; Harrington, D. Detection of Membrane Drying, Fuel Cell Flooding, and Anode Catalyst Poisoning on PEMFC Stacks by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A857–A864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, C.; Specchia, S.; Saracco, G.; Specchia, V. CO-selective methanation over Ru–γAl2O3 catalysts in H2-rich gas for PEM FC applications. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Weidner, J.W. Analysis of an Electrochemical Filter for Removing Carbon Monoxide from Reformate Hydrogen. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, E231–E236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Subramanian, A.; Kisslinger, K.; Zuo, X.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Yin, Y.; Nam, C.-Y.; Rafailovich, M.H. Suppression of Carbon Monoxide Poisoning in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells via Gold Nanoparticle/Titania Ultrathin Film Heterogeneous Catalysts. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 3479–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Amphlett, J.C.; Mann, R.F.; Peppley, B.A.; Roberge, P.R. Carbon monoxide poisoning of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. In Proceedings of the IECEC-97 Proceedings of the Thirty-Second Intersociety Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 July–1 August 1997; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 768–773. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, H.; Bacquart, T.; Perkins, M.; Moore, N.; Ihonen, J.; Hinds, G.; Smith, G. Operando characterisation of the impact of carbon monoxide on PEMFC performance using isotopic labelling and gas analysis. J. Power Sources Adv. 2020, 6, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Haque, M.S.; Hasan, M.; Hakim, M.A. Fabrication of Bismuth Vanadate (BiVO4) Nanoparticles by a Facile Route. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2019, 20, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.A.; Porembsky, V.I.; Fateev, V.N. Pure hydrogen production by PEM electrolysis for hydrogen energy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettcher, S.W. Introduction to Green Hydrogen. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 13095–13098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Hydrogen Production: Electrolysis. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-production-electrolysis (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Beck, A.; Yang, A.C.; Leland, A.R.; Riscoe, A.R.; Lopez, F.A.; Goodman, E.D.; Cargnello, M. Understanding the preferential oxidation of carbon monoxide (PrOx) using size-controlled Au nanocrystal catalyst. AIChE J. 2018, 64, 3159–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Mei, J.; Tang, X.; Jiang, J.; Sun, C.; Song, K. The Degradation Prediction of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Performance Based on a Transformer Model. Energies 2024, 17, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion Power. Manufacturer of Value-Added Products Containing Nafion™. Available online: https://ion-power.com/nafion-research/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Perma Pure. The Basic Physical and Chemical Properties of Nafion™ Polymer. Available online: https://www.permapure.com/environmental-scientific-old/nafion-tubing/nafion-physical-and-chemical-properties/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Foniok, K.; Drozdova, L.; Prokop, L.; Krupa, F.; Kedron, P.; Blazek, V. Mechanisms and Modelling of Effects on the Degradation Processes of a Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Fuel Cell: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun Lim, H.; Kim, G.; Jin Yun, G. Durability and Performance Analysis of Polymer Electrolyte Membranes for Hydrogen Fuel Cells by a Coupled Chemo-mechanical Constitutive Model and Experimental Validation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 24257–24270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Jiang, R.; Elbaccouch, M.; Muradov, N.; Fenton, J.M. On-board removal of CO and other impurities in hydrogen for PEM fuel cell applications. J. Power Sources 2006, 162, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, S.; Soler, J.; Valenzuela, R.X.; Daza, L. Assessment of the performance of a PEMFC in the presence of CO. J. Power Sources 2005, 151, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrette, L.P.L.; Friedrich, K.A.; Hubera, M.; Stimming, U. Improvement of CO tolerance of proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells by a pulsing technique. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Rihko-Struckmann, L.; Sundmacher, K. Spontaneous oscillations of cell voltage, power density, and anode exit CO concentration in a PEM fuel cell. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 18179–18185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruta, M. Gold as a novel catalyst in the 21st century: Preparation, working mechanism, and applications. Gold Bull. 2004, 37, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, I.X.; Tang, W.; McEntee, M.; Neurock, M.; Yates, J.T., Jr. Inhibition at perimeter sites of Au/TiO2 oxidation catalyst by reactant oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12717–12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, I.X.; Tang, W.; Neurock, M.; Yates, J.T., Jr. Insights into Catalytic Oxidation at the Au/TiO2 Dual Perimeter Sites. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 47, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-S.; Sun, H.; Wang, L.-C.; Liu, Y.-M.; Fan, K.-N.; Cao, Y. Morphology effects of nanoscale ceria on the activity of Au/CeO2 catalysts for low-temperature CO oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 90, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Wang, A.; Yang, X.; Allard, L.F.; Jiang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, T. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, A.S.; Slavinskaya, E.M.; Gulyaev, R.V.; Zaikovskii, V.I.; Stonkus, O.A.; Danilova, I.G.; Plyasova, L.M.; Polukhina, I.A.; Boronin, A.I. Metal–support interactions in Pt/Al2O3 and Pd/Al2O3 catalysts for CO oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 97, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Pan, C.; Zhao, S.; Liu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Rafailovich, M.H. Enhancing performance of PEM fuel cells: Using the Au nanoplatelet/Nafion interface to enable CO oxidation under ambient conditions. J. Catal. 2016, 339, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perala, S.R.K.; Kumar, S. On the Mechanism of Metal Nanoparticle Synthesis in the Brust–Schiffrin Method. Langmuir 2013, 29, 9863–9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Savanur, M.R.S.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Asnani, K.; Kumar, B.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, S. Recent Advances in Silver Nanoparticles-Catalyzed Reactions. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202403655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-Y.; Gao, Z.-W.; Yang, K.-F.; Zhanga, W.-Q.; Xu, L.-W. Nanosilver: A new generation of silver catalysts for organic transformations in the efficient synthesis of fine chemicals. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 2554–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Dhal, G.C. Applications of silver nanocatalysts for low-temperature oxidation of carbon monoxide. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 110, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Soubaihi, R.M.; Saoud, K.M.; Dutta, J. Low-temperature CO oxidation by silver nanoparticles in silica aerogel mesoreactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brust, M.; Walker, M.; Bethell, D.; Schiffrin, D.J.; Whyman, R. Synthesis of thiol-derivatised gold nanoparticles in a two-phase liquid–liquid system. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 7, 801–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Srinivasan, M.P.; Dharmarajan, R. Synthesis of short-chain thiol-capped gold nanoparticles, their stabilization, and immobilization on silicon surface. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 390, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsley, S.; Edwards, W.; Mati, I.K.; Poss, G.; Diez-Castellnou, M.; Marro, N.; Kay, E.R. A General One-Step Synthesis of Alkanethiyl-Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles with Control over Core Size and Monolayer Functionality. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 6168–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motte, L.; Pileni, M.P. Influence of Length of Alkyl Chains Used to Passivate Silver Sulfide Nanoparticles on Two- and Three-Dimensional Self-Organization. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 4104–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallipurath, A.; Nicoletti, O.; Skelton, J.M.; Mahajan, S.; Midgley, P.A.; Elliott, S.R. Surfactant-free coating of thiols on gold nanoparticles using sonochemistry: A study of competing processes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 1886–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hock, N.; Racaniello, G.F.; Aspinall, S.; Denora, N.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Thiolated Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: Mimicking the Workhorses of Our Body. Adv. Sci. 2021, 9, 2102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinterwirth, H.; Kappel, S.; Waitz, T.; Prohaska, T.; Lindner, W.; Lämmerhofer, M. Quantifying Thiol Ligand Density of Self-Assembled Monolayers on Gold Nanoparticles by Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, K.; Kaplan, M.; Çalış, S. Effects of nanoparticle size, shape, and zeta potential on drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 666, 124799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernihough, O.; Ismail, M.S.; El-Kharouf, A. Intermediate Temperature PEFCs with Nafion® 211 Membrane Electrolytes: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Membranes 2022, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, H.R.; Nores-Pondal, F.; Buera, M.P. Low temperature thermal properties of Nafion 117 membranes in water and methanol-water mixtures. J. Power Sources 2006, 161, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barique, M.A.; Tsuchida, E.; Ohira, A.; Tashiro, K. Effect of Elevated Temperatures on the States of Water and Their Correlation with the Proton Conductivity of Nafion. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S. Temperature sensitivity characteristics of PEM fuel cell and output performance improvement based on optimal active temperature control. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 206, 123966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Liu, M.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Grigoriev, S.; Hasanien, H.; Tang, X.; Li, R.; Sun, C. Polarization loss decomposition-based online health state estimation for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 2, 150162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvolbæk, B.; Janssens, T.; Clausen, B.; Falsig, H.; Christensen, C.; Nørskov, J. Catalytic activity of Au nanoparticles. Nano Today 2007, 2, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Molecular Formula | Chemical Structure |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Hexanethiol (C6) | C6H14S | CH3–(CH2)5–SH |

| 1-Octanethiol (C8) | C8H18S | CH3–(CH2)7–SH |

| 1-Decanethiol (C10) | C10H22S | CH3–(CH2)9–SH |

| 1-Dodecanethiol (C12) | C12H26S | CH3–(CH2)11–SH |

| 1-Tetradecanethiol (C14) | C14H30S | CH3–(CH2)13–SH |

| Pt Load (mg/cm2) | Cell Area (cm2) | Temperature (°C) | Relative Humidity (RH%) | Flow Rate | Back Pressure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anode (SCCM) | Cathode (SCCM) | Anode (kPa) | Cathode (kPa) | ||||

| 0.1 | 16 | 30, 60, 90 | 100 | 60 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

| Crystal System | Space Group | Lattice Parameters | Unit Cell Volume, V (Å)3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a = b = c (Å) | α = β = γ | |||

| Face-centered Cubic | F m-3 m | 4.08550 | 90° | 68.1923 |

| Type of Ag NP | Crystallite Size (nm) | Lattice Strain (%) |

|---|---|---|

| C6 | 13.75 | 0.008 |

| C8 | 13.6 | 0.008 |

| C10 | 12.71 | 0.009 |

| C12 | 2.83 | 0.039 |

| C14 | 2.95 | 0.039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rahman, M.F.; Fang, H.; Raut, A.; Sloutski, A.; Rafailovich, M. Investigation of the Effect of Alkyl Chain Length on the Size and Distribution of Thiol-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Applications. Membranes 2026, 16, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020058

Rahman MF, Fang H, Raut A, Sloutski A, Rafailovich M. Investigation of the Effect of Alkyl Chain Length on the Size and Distribution of Thiol-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Applications. Membranes. 2026; 16(2):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020058

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahman, Md Farabi, Haoyan Fang, Aniket Raut, Aaron Sloutski, and Miriam Rafailovich. 2026. "Investigation of the Effect of Alkyl Chain Length on the Size and Distribution of Thiol-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Applications" Membranes 16, no. 2: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020058

APA StyleRahman, M. F., Fang, H., Raut, A., Sloutski, A., & Rafailovich, M. (2026). Investigation of the Effect of Alkyl Chain Length on the Size and Distribution of Thiol-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Applications. Membranes, 16(2), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020058