Eco-Friendly Ceramic Membranes from Natural Clay and Almond Shell Waste for the Removal of Dyes and Drugs from Wastewater

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

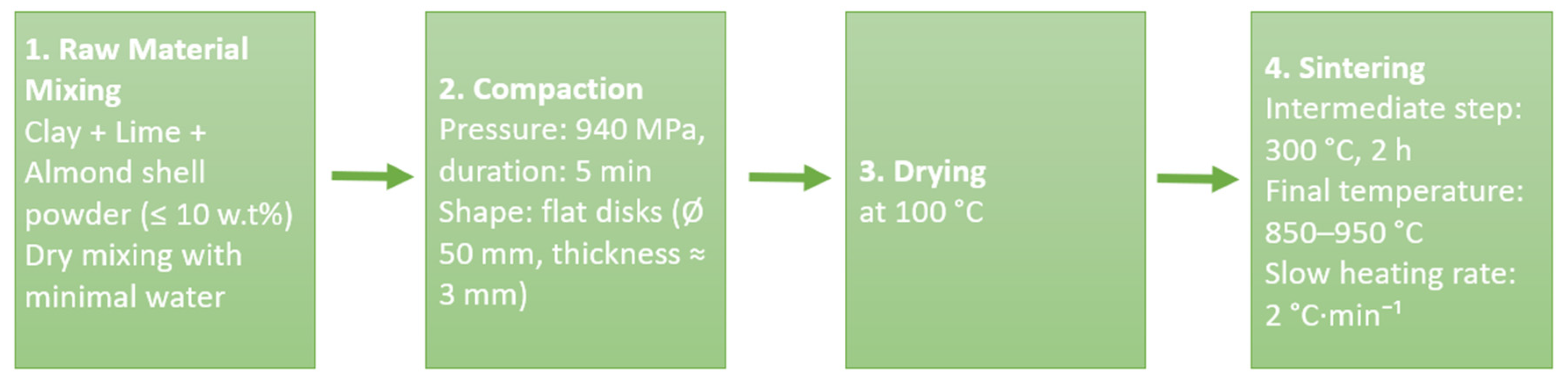

2.2. Preparation of MK Membranes

2.3. Membrane Characterization

2.4. Filtration Performance of MK Membranes

2.5. Evaluation of Fouling Resistance

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Flat Ceramic Membranes

3.1.1. Shrinkage

3.1.2. Porosity and Mechanical Strength

3.1.3. Chemical Resistance

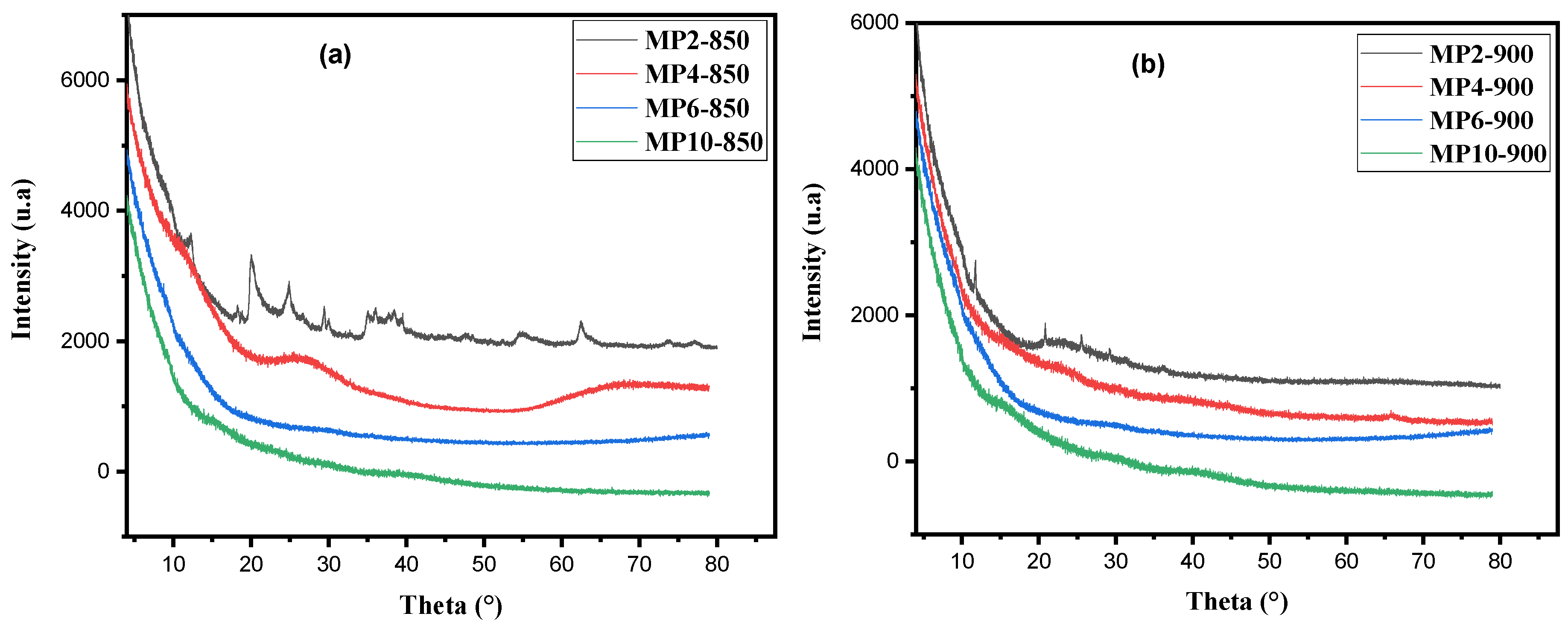

3.1.4. XRD Analysis

3.1.5. FTIR Analysis

3.1.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3.1.7. Morphology Analysis

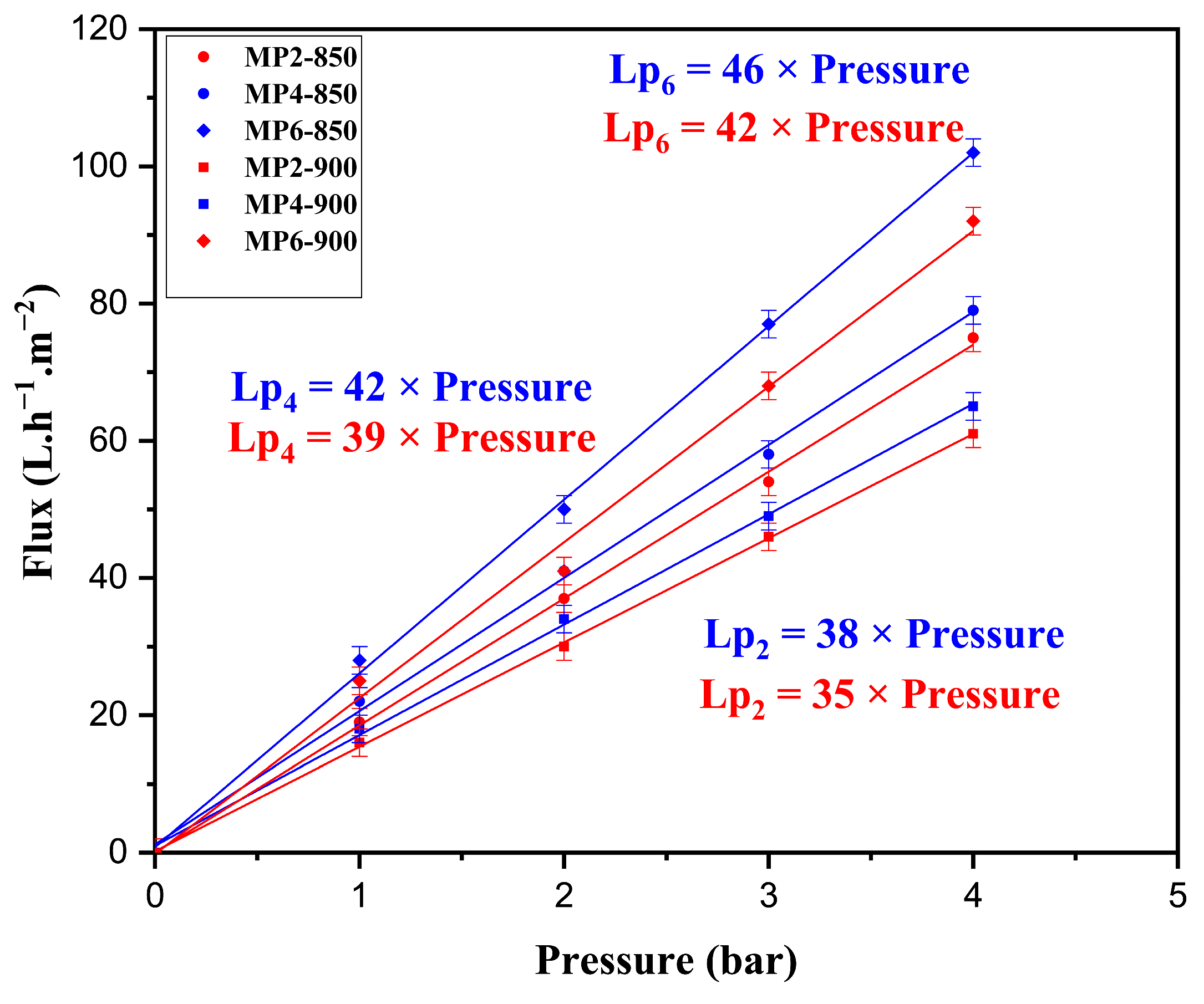

3.1.8. Permeability Test

3.1.9. Determination of the Isoelectric Point (pHiso) of the Prepared Membranes

3.2. Application for Crystal Violet and Paracetamol Removal from Aqueous Solution

3.2.1. Novel Membrane Performance

- For CV: 34, 31, 41, 34, 43, and 39 L·h−1·m−2 for membranes MP2-850, MP2-900, MP4-850, MP4-900, MP6-850, and MP6-900, respectively;

- For PCT: the stabilized flux was of 35, 32, 42, 36, 44, and 43 L·h−1·m−2 (Figure 11a,b). This trend can be primarily attributed to the deposition and accumulation of the recalcitrant molecules on the membrane surfaces, which depend on the characteristics of the membranes.

3.2.2. Determination of the Fouling Coefficients and Membrane Regeneration

Determination of Fouling Coefficients

Determination of Membrane Regeneration

3.2.3. Membrane Cost Estimation

3.3. Comparative Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rani, S.L.S.; Kumar, R.V. Insights on Applications of Low-Cost Ceramic Membranes in Wastewater Treatment: A Mini-Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmiri, Y.; Attia, A.; Jallouli, N.; Chabanon, E.; Charcosset, C.; Mahouche Chergi, S.; Algieri, C.; Chakraborty, S.; Ben Amar, R. Synthesis of a Cost-Effective ZnO/Zeolite Photocatalyst for Paracetamol Removal. Emergent Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrouni, J.; Aloulou, H.; Attia, A.; Dammak, L.; Ben Amar, R. Surface modification of a zeolite microfiltration membrane: Characterization and application to the treatment of colored and oily wastewaters. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 4513–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Fan, Y. State-of-the-art developments in fabricating ceramic membranes with low energy consumption. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 14966–14987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, T.; Abdelmjid, B.; Ahlam, E.; Abdelaali, K.; Abdellah, A.; Mohamed, O.; Rachid Alami Younssi, S. Manufacture and characterization of flat microfiltration membrane based on Moroccan pyrophyllite clay for pretreatment of raw seawater for desalination: A Review. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 253, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saja, S.; Bouazizi, A.; Achiou, B.; Ouammou, M.; Albizane, A.; Bennazha, J.; Alami Younssi, S. Elaboration and characterization of low-cost ceramic membrane made from natural Moroccan perlite for treatment of industrial wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, F.; Gray, S. Cost and efficiency perspectives of ceramic membranes for water treatment. Water Res. 2022, 220, 118629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoui, M.; Limousy, L. Low-cost ceramic membranes: Synthesis, classifications, and applications. C. R. Chim. 2019, 22, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmiri, Y.; Attia, A.; Aloulou, H.; Dammak, L.; Baklouti, L.; Ben Amar, R. Preparation and Characterization of New and Low-Cost Ceramic Flat Membranes Based on Zeolite-Clay for the Removal of Indigo Blue Dye Molecules: A Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 10865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defriend Obrey, K.A.; Wiesner, M.; Barron, A.R. Alumina and aluminate ultrafiltration membranes derived from alumina nanoparticles. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 224, 11–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suna, L.; Wang, Z.; Gaob, B. Ceramic membranes originated from cost-effective and abundant natural minerals and industrial wastes for broad applications: A Review. Desal. Water Treat. 2020, 201, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadawi, M.; Mosalagae, M.; Reaney, I.; Meredith, J. Guar gum: A novel binder for ceramic extrusion. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 16727–16735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousbih, S.; Errais, E.; Darragi, F.; Duplay, J.; Malika, T.-A.; Michael Olawale, D.; Ben Amar, R. Treatment of textile wastewater using monolayered ultrafiltation ceramic membrane fabricated from natural kaolin clay: A Review. Environ. Technol. 2021, 42, 3348–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franca, S.A.S.; Santana, N.L.S.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Romualdo, R.M.; Rafaela, R.A.; Lira, H.L. Ceramic membranes production using quartzite waste for treatment of domestic water. Int. J. Adv. Ceram. 2025, 22, e14986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagdali, S.; Miyah, Y.; El Habacha, M.; Mahmoudy, G.; Benjalloun, M.; Iaich, S.; Zerbet, M.; Chiban, M.; Sinan, F. Performance assessment of a phengite clay-based flat membrane for microfiltration of real-wastewater from clothes washing: Characterization, cost estimation, and regeneration. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakcho, Y.; Mouiya, M.; Bouazizi, A.; Abouliatim, Y.; Sehaqui, H.; Mansouri, S.; Benhammou, A.; Hannache, H.; Alami, J.; Abourriche, A. Treatment of seawater and wastewater using a novel low-cost ceramic membrane fabricated with red clay and tea waste: A Review. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, A.; Gao, L.; Kong, L.; Oraaji, Y.; Zhao, S. Waste-derived low-cost ceramic membranes for water treatment: Opportunities, challenges and future directions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoussi, H.; Osmani, H.; Courtois, C.; Bourahli, M.E.H. Mineralogical and Chemical Characterization of DD3 Kaolin from the East of Algeria. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2016, 55, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Hao, J.; Wang, W. Study of Almond Shell Characteristics: A Review. Materials 2018, 11, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrouni, J.; Attia, A.; Elberrichi, F.Z.; Dammak, L.; Baklouti, L.; Ben Aissa, M.-A.; Ben Amar, R.; Deratani, A. Green and Sustainable Clay Ceramic Membrane Preparation and Application to Textile Wastewater Treatment for Color Removal. Membranes 2025, 15, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjema, B.; Achiou, B.; Boulkrinat, A.; Elomari, H.; Bouazizi, A.; Ouammou, M.; Bennazha, J. Fabrication and characterization of low-cost ceramic membranes for wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, W.; Canfield, N. Development of thin porous metal sheet as micro-filtration membrane and inorganic membrane support. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 409, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veréb, G.; Kassai, P.; Nascimben Santos, E.; Arthanareeswaran, G.; Hodúr, C.; László, Z. Intensification of the Ultrafiltration of Real Oil-Contaminated Water with Per-Ozonation and/or with TiO2, TiO2/CNT Nanomaterial-Coated Membrane Surfaces. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22195–22205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgada, A.; Achiou, B.; Younssi, S.; Fatima Zohra, C.; Mohamed, O.; Jason, A.C.; Rachid, B.; Khaoula, M. Low-Cost Ceramic Microfiltration Membrane Made from Natural Phosphate for Pretreatment of Raw Seawater for Desalination. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beqqour, D.; Achiou, B.; Bouazizi, A.; Ouaddari, H.; Elomari, H.; Ouammou, M.; Bennazha, J.; Alami Younssi, S. Enhancement of Microfiltration Performances of Pozzolan Membrane by Incorporation of Micronized Phosphate and Its Application for Industrial Wastewater Treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, A.; Saja, S.; Achiou, B.; Ouammou, M.; Calvo, J.I.; Aaddane, A.; Younssi, S.A. Elaboration and Characterization of a New Flat Ceramic Microfiltration Membrane Made from Natural Moroccan Bentonite for Industrial Wastewater Treatment. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 132, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamor, I. Elaboration des membranes céramiques de microfiltration. Master’s Thesis, Ecole Nationale Polytechnique, University of Algiers, El Harrach, Algeria, 10 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Q.; Lim, Y.J.; Wang, R. Chemically Robust Hollow Fiber Thin-film Composite Membranes Based on Polyurea Selective Layers for Nanofiltration under Extreme pH Conditions. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 738, 124818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountoumnjou, O.; Szymczyk, A.; Enjema Lyonga Mbambyah, E.; Njoya, D.; Elimbi, A. New Low-Cost Ceramic Microfiltration Membranes for Bacteria Removal. Membranes 2022, 12, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, D.P.; Monson, A.; Urban-Klaehn, J. Sintering Study of Digital Light Process-Printed Zeolite by Positron, Thermogravimetric and X-Ray Techniques. Next Mater. 2024, 3, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura Brito, F.G.L.; Cardoso, V.S.T.; Lopes, C.L.; Henriques, D.J.; Lima, A.P.; Mansur, H.S. Multi-Functional Eco-Friendly 3D Scaffolds Based on N-Acyl Thiolated Chitosan for Potential Adsorption of Methyl Orange and Antibacterial Activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr Allah Ali, A.; Saied, M.H.; Mostafa, M.Z.; Abdel-Moneim, T.M. A survey of maximum PPT techniques of PV systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Energytech, Cleveland, OH, USA, 29–31 May 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yan, C.; Alshameri, A.; Qiu, X.; Zhou, C.; Li, D. Synthesis and Characterization of 13X Zeolite from Low-Grade Natural Kaolin. Adv. Powder Technol. 2014, 25, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakib, S.; Sghyar, M.; Rafiq, M.; Cot, D.; Larbot, A.; Cot, L. Elaboration and Characterization of Porous Ceramics Based on Granitic Sand Using an Extrusion Process. Ann. Chim. Sci. Matér. 2000, 25, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Chun-Wei Lin, J.; Srivastava, G.; Djenour, Y. A Nutrient Recommendation System for Soil Fertilization Based on Evolutionary Computation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid Rekik, S.; Gassara, S.; Bouaziz, J.; Deratan, A.; Baklouti, S. Development and Characterization of Porous Membranes Based on Kaolin/Chitosan Composite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 143, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayehi, M.; Dhouib Sahnoun, R.; Fakhfakh, S.; Baklouti, S. Effect of Elaboration Parameters of a Ceramic Membrane on the Filtration Process Efficacy. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 5202–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, S.; Uzal, N. Preparation and Characterization of PSF/PEI/CaCO3 Nanocomposite Membranes for Oil/Water Separation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 25315–25326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matin, A.; Jillani, S.M.S.; Baig, U.; Ihsanullah, I.; Alhooshani, K. Removal of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds from Water Sources Using Nanofiltration and Reverse Osmosis Membranes: Comparison of Removal Efficiencies and In-Depth Analysis of Rejection Mechanisms. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 338, 117682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanth, D.; Pugazhenthi, G.; Uppaluri, R. Biomass assisted microfiltration of chromium (VI) using Baker’s yeast by ceramic membrane prepared from low-cost raw materials. Desalination 2012, 285, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risqi, U.; Saputra, M.; Markhan, A.; Triqoni, N. Visual SLAM and Structure from Motion in Dynamic Environments. Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouiya, M.; Bouaziz, A.; Abourriche, A.; El Khessaimi, Y.; Benhammou, A.E.Y.; Taha, Y. Effect of Sintering Temperature on the Microstructure and Mechanical Behavior of Porous Ceramics Made from Clay and Banana Peel Powder. Results Mater. 2019, 4, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Membrane | Clay (wt.%) | Lime (wt.%) | Almond Shell (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP-2 | 96 | 2 | 2 |

| MP-4 | 94 | 2 | 4 |

| MP-6 | 92 | 2 | 6 |

| MP-10 | 88 | 2 | 10 |

| MP2-900 | MP4-900 | MP6-900 | MP10-900 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | 61.4 | 66.5 | 61.2 | 62.6 |

| Al | 14.1 | 17.0 | 14.7 | 14.4 |

| Mn | 13.7 | - | 12.6 | - |

| Si | 7.6 | 15.4 | 9.1 | 12.8 |

| Ni | 2.0 | - | 1.4 | - |

| Ca | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.9 |

| S | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| C | - | - | - | 7.9 |

| Membrane | Jw1 (L·m−2·h−1) | Jwf (L·m−2·h−1) | Jw2 (L·m−2·h−1) | FRR (%) | Rt (%) | Rr (%) | Rir (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP2-850 | 38.0 | 35.0 | 34.0 | 89.5 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 10.5 |

| MP4-850 | 42.0 | 41.5 | 41.0 | 97.6 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| MP6-850 | 46.0 | 44.0 | 43.0 | 93.6 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 4.3 |

| MP2-900 | 35.0 | 32.0 | 31.0 | 88.3 | 11.4 | 2.9 | 5.6 |

| MP4-900 | 39.0 | 36.0 | 34.0 | 87.2 | 12.8 | 5.1 | 7.7 |

| MP6-900 | 42.0 | 40.0 | 39.0 | 92.9 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 7.1 |

| Membrane | Jw1 (L·m−2·h−1) | Jwf (L·m−2·h−1) | Jw2 (L·m−2·h−1) | FRR (%) | Rt (%) | Rr (%) | Rir (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP2-850 | 38.0 | 34.0 | 33.0 | 86.8 | 13.2 | 2.6 | 10.5 |

| MP4-850 | 42.0 | 41.0 | 40.0 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| MP6-850 | 46.0 | 43.0 | 42.0 | 91.3 | 8.7 | 2.2 | 5.4 |

| MP2-900 | 35.0 | 31.0 | 30.0 | 85.7 | 14.3 | 2.9 | 6.5 |

| MP4-900 | 39.0 | 34.0 | 33.0 | 84.6 | 15.4 | 2.6 | 12.8 |

| MP6-900 | 42.0 | 39.0 | 37.0 | 88. | 11.9 | 4.8 | 7.1 |

| Price of Raw Materials | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Unit per Kg ($) | Amount of Raw Material (g) | Price ($) |

| kaolin powder | 0.5 | 19.2 | 0.010 |

| Lime | - | 0.4 | 0.008 |

| Almond shells | - | 0.4 | - |

| Total raw materials cost for the fabrication of 1 membrane | 0.018 | ||

| Energy cost (Based on power consumption) | |||

| Dry oven | 0.027 | ||

| Presse | 3.245 | ||

| Furnace | 0.086 | ||

| Total production cost for the fabrication of 1 membrane ($) | 3.358 | ||

| (Surface of membrane = 1.7 × 10−3 m2) | |||

| Total production cost of the (MP2) Kaolin membrane ($ m−2) | 3.376 | ||

| Reference | Raw Materials of Ceramic Membrane | Fabrication Technique | Sintering Temperature (°C) | Porosity (%) | Permeability (L·h−1·m−2·bar−1) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Applications and Removal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | Moroccan red clay with tea waste | Uniaxial pressing | 1100 | 39.1 | 1249 | 14.8 | Seawater: 99.76% |

| [14] | ball clay, quartzite waste, and corn starch | 1000 | 35.0 | 203 | 8.6 | Treatment of domestic laundry wastewater: >91% | |

| [15] | Natural Moroccanphengite clay | 1050 | 34.5 | 43.5 | 26.7 | pretreated real wastewater (RWW3) from local clothes washing: 100% | |

| [42] | Ceramic Membrane From Clay and banana peel | 1100 | 40.3 | 550 | 19.2 | Not specified | |

| This work | Algerian clay, Almond shell, and Lime | 900 | 12.5 | 35.0 | 25.0 | Treatment of PCT: 87% Treatment of CV: 87% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bahrouni, J.; Aouay, F.; Larchet, C.; Dammak, L.; Ben Amar, R. Eco-Friendly Ceramic Membranes from Natural Clay and Almond Shell Waste for the Removal of Dyes and Drugs from Wastewater. Membranes 2026, 16, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020052

Bahrouni J, Aouay F, Larchet C, Dammak L, Ben Amar R. Eco-Friendly Ceramic Membranes from Natural Clay and Almond Shell Waste for the Removal of Dyes and Drugs from Wastewater. Membranes. 2026; 16(2):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020052

Chicago/Turabian StyleBahrouni, Jamila, Feryelle Aouay, Christian Larchet, Lasâad Dammak, and Raja Ben Amar. 2026. "Eco-Friendly Ceramic Membranes from Natural Clay and Almond Shell Waste for the Removal of Dyes and Drugs from Wastewater" Membranes 16, no. 2: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020052

APA StyleBahrouni, J., Aouay, F., Larchet, C., Dammak, L., & Ben Amar, R. (2026). Eco-Friendly Ceramic Membranes from Natural Clay and Almond Shell Waste for the Removal of Dyes and Drugs from Wastewater. Membranes, 16(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020052