Toward Rational Design of Ion-Exchange Nanofiber Membranes: Meso-Scale Computational Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Protein Adsorption on Ion-Exchange (IEX) Nanofibre Membranes

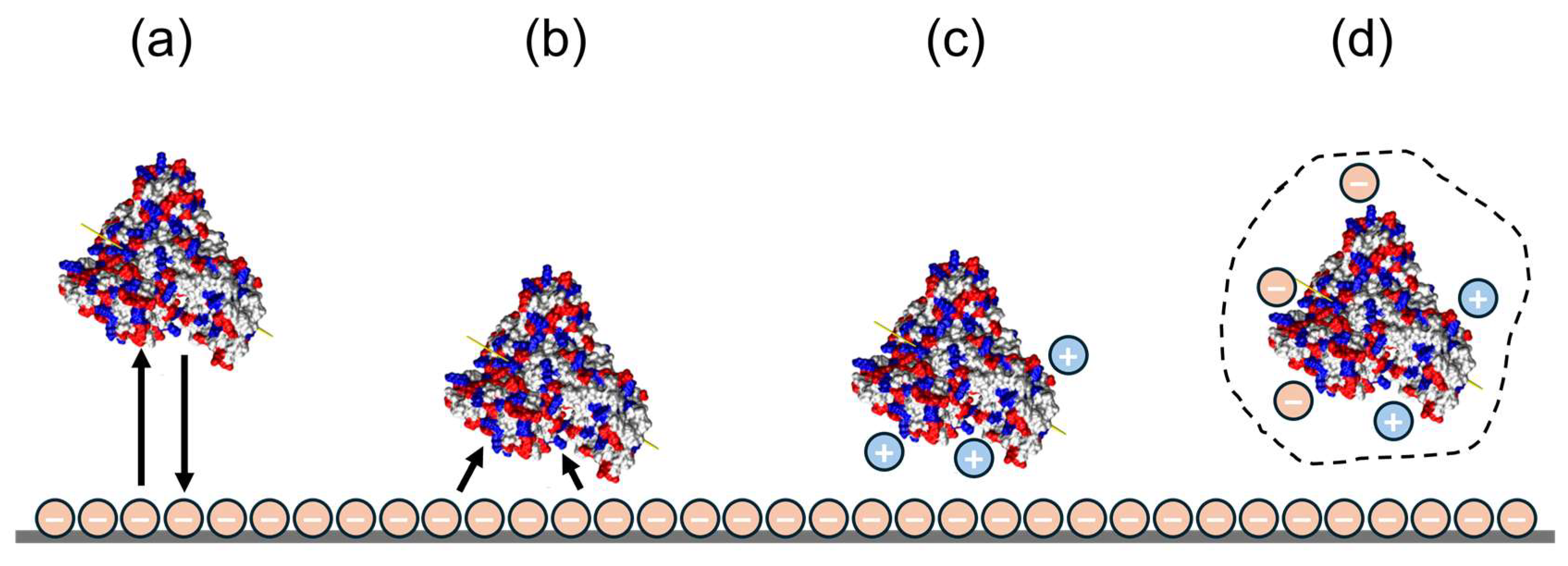

2.1. Separation Mechanism of IEX Binding

2.2. Factors Impacting the Binding of Proteins on IEX Nanofibres

2.2.1. Adsorbent Structural Effect

2.2.2. Protein Properties

2.2.3. Solution Parameters

3. Modelling Approaches for Protein Binding

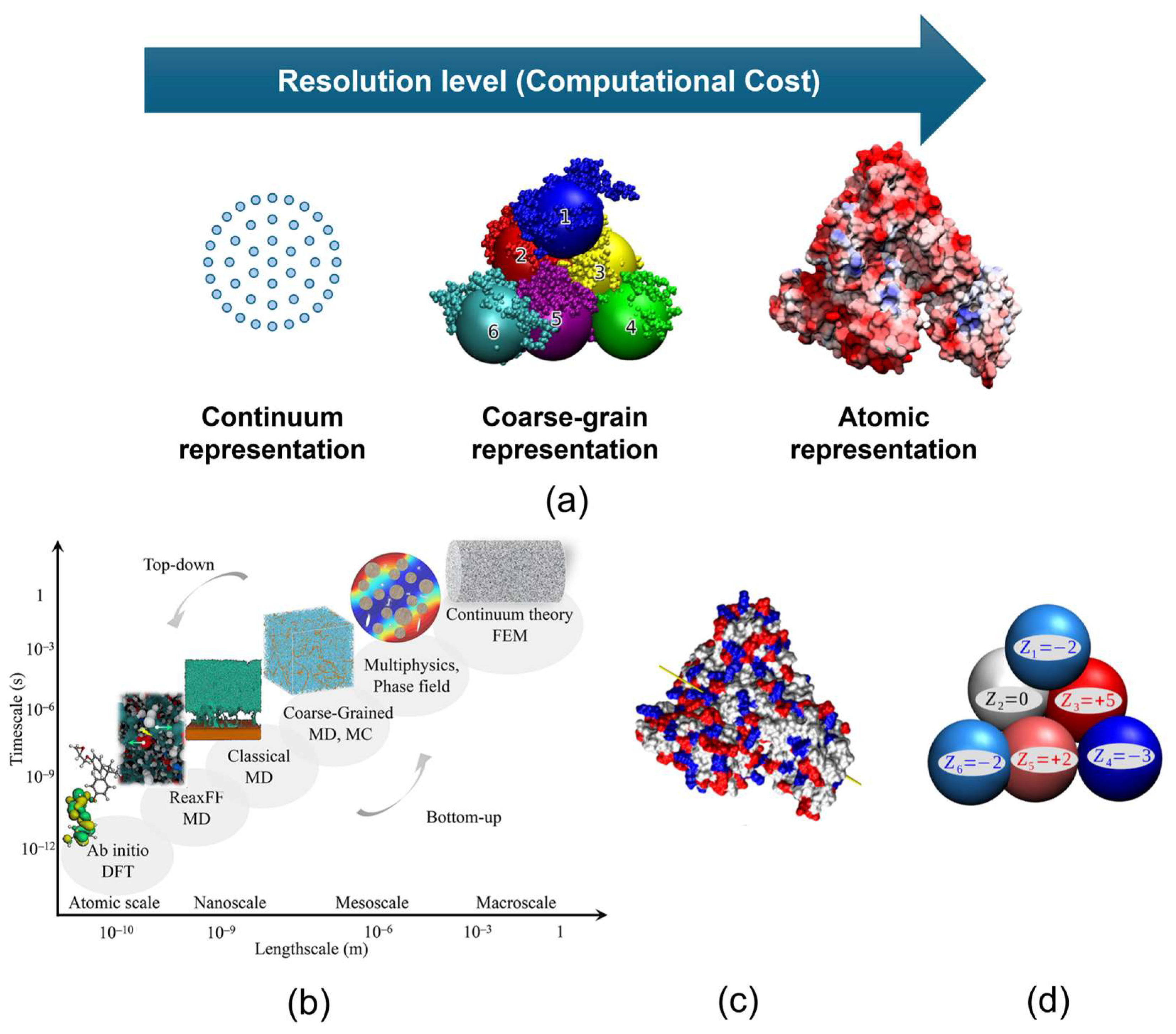

3.1. Modelling Frameworks for Ion-Exchange Protein Binding

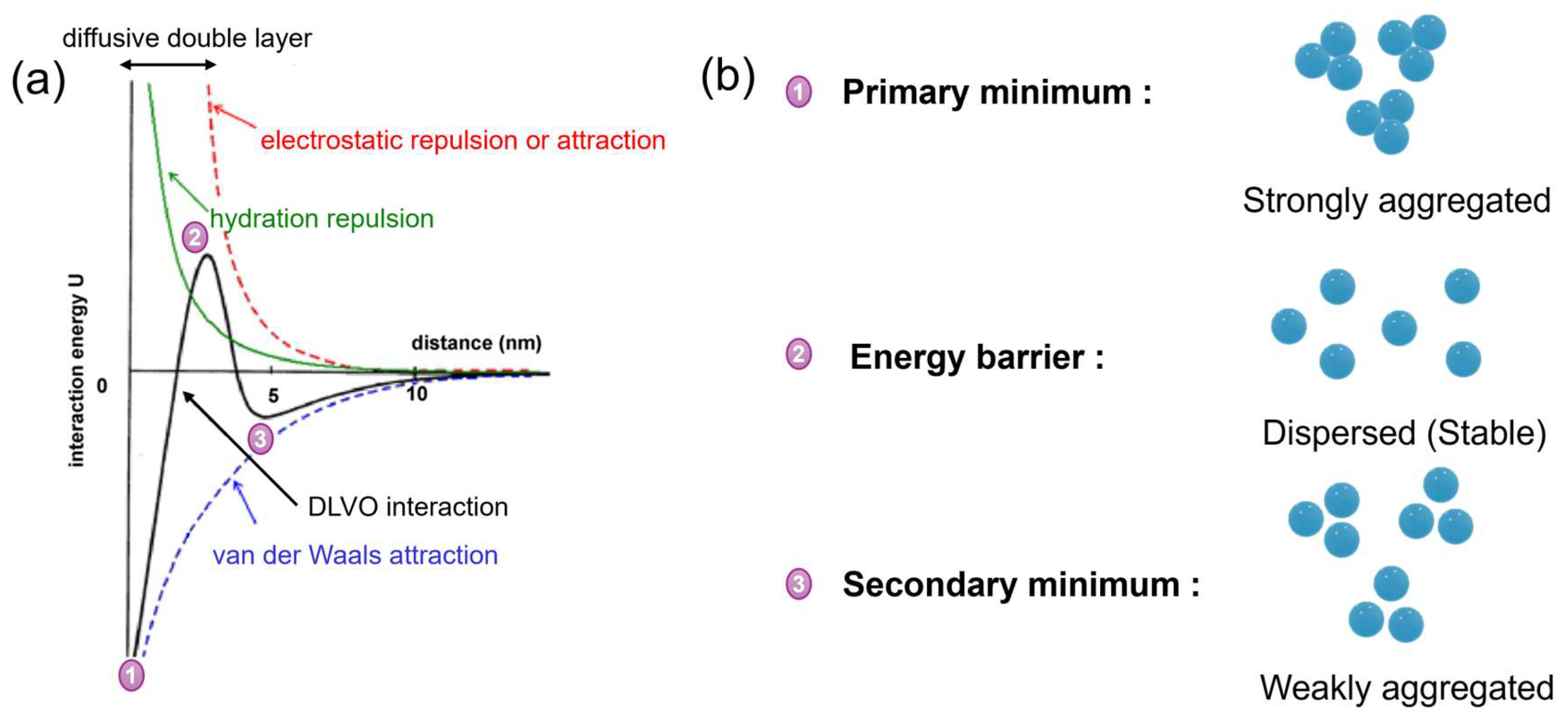

3.2. Application of DLVO Theory to Protein Binding on IEX Nanofibres

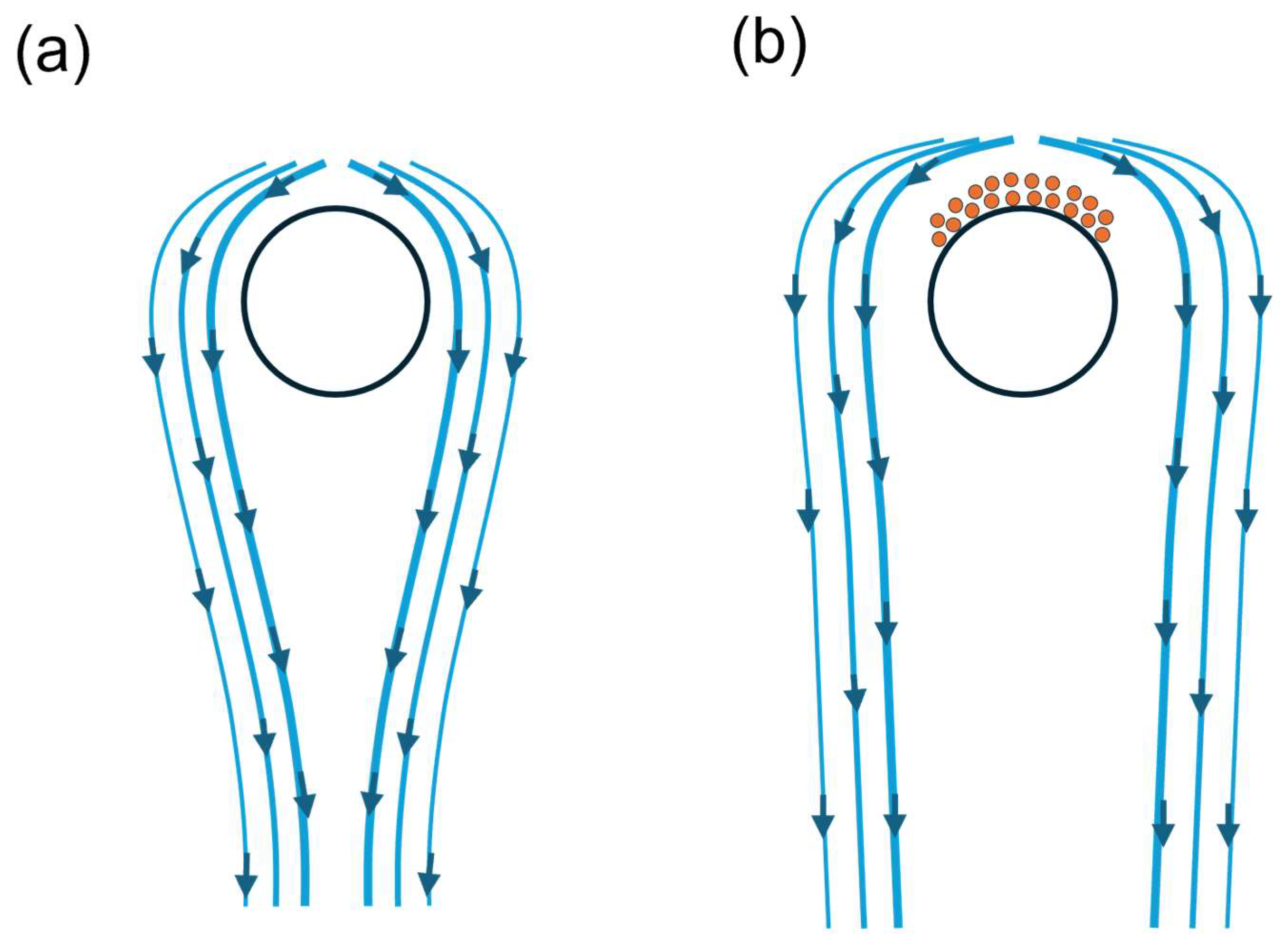

3.3. Dynamics of Fibre–Protein Interactions

3.4. Influence of Protein–Protein Interactions During Binding

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, X.; Merenda, A.; Al-Attabi, R.; Dumée, L.F.; Zhang, X.; Thang, S.H.; Pham, H.; Kong, L. Towards next generation high throughput ion exchange membranes for downstream bioprocessing: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 647, 120325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydney, A.L. New developments in membranes for bioprocessing—A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 620, 118804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, J.-C.; Rydén, L. Protein Purification: Principles, High Resolution Methods, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaos, E.L. Handbook on Protein Purification: Industry Challenges and Technological Developments; Nova: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstweiler, L.; Bi, J.; Middelberg, A.P.J. Continuous downstream bioprocessing for intensified manufacture of biopharmaceuticals and antibodies. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 231, 116272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.; Devine, T.; O’Kennedy, R. Technology advancements in antibody purification. Antib. Technol. J. 2016, 6, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yu, B.; Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Cong, H. Recent advances on protein separation and purification methods. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 284, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yu, B.; Cong, H.; Shen, Y. Recent development and application of membrane chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Stern, D.; Lock, L.L.; Mills, J.; Ou, S.-H.; Morrow, M.; Xu, X.; Ghose, S.; Li, Z.J.; Cui, H. Emerging biomaterials for downstream manufacturing of therapeutic proteins. Acta Biomater. 2019, 95, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saufi, S.M.; Fee, C.J. Mixed matrix membrane chromatography based on hydrophobic interaction for whey protein fractionation. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 444, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Chu, J.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, J. Surface modification of regenerated cellulose membrane based on thiolactone chemistry—A novel platform for mixed mode membrane adsorbers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 511, 145539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.F.; Ma, J.; Winter, C.; Bayer, R. Recovery and purification process development for monoclonal antibody production. mAbs 2010, 2, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, P. Modeling of Controlled-Shear Affinity Filtration Using Computational Fluid Dynamics and a Novel Zonal Rate Model for Membrane Chromatography. Doctoral Dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lalli, E.; Silva, J.S.; Boi, C.; Sarti, G.C. Affinity Membranes and Monoliths for Protein Purification. Membranes 2020, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Duan, C.; Yan, Z.; Si, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Electrospun nanofibrous composite materials: A versatile platform for high efficiency protein adsorption and separation. Compos. Commun. 2018, 8, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Wang, X.; Si, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Scalable Fabrication of Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes Functionalized with Citric Acid for High-Performance Protein Adsorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 11819–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel-Roos, S.; Stein, D.; Strube, J. Evaluation of Continuous Membrane Chromatography Concepts with an Enhanced Process Simulation Approach. Antibodies 2018, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hsia, T.; Merenda, A.; Al-Attabi, R.; Dumee, L.F.; Thang, S.H.; Kong, L. Constructing novel nanofibrous polyacrylonitrile (PAN)-based anion exchange membrane adsorber for protein separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 285, 120364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.S.; Kumar, D.; Kateja, N. Recent developments in chromatographic purification of biopharmaceuticals. Biotechnol. Lett 2018, 40, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borneman, Z.; Groothuis, B.; Willemsen, M.; Wessling, M. Coiled fiber membrane chromatography. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 346, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boi, C.; Malavasi, A.; Carbonell, R.G.; Gilleskie, G. A direct comparison between membrane adsorber and packed column chromatography performance. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1612, 460629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque, A.C.A.; Pina, A.S.; Azevedo, A.M.; Aires-Barros, R.; Jungbauer, A.; Di Profio, G.; Heng, J.Y.Y.; Haigh, J.; Ottens, M. Anything but Conventional Chromatography Approaches in Bioseparation. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 15, 1900274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-de-la-Peña, A.M.; González-Valdez, J.; Aguilar, O. Protein A chromatography: Challenges and progress in the purification of monoclonal antibodies. J. Sep. Sci. 2019, 42, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, P.; Liu, N.; Wan, Y.; Guo, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Liu, K.; Lu, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, D. Highly efficient nanofibrous sterile membrane with anti-BSA/RNA-fouling surface via plasma-assisted carboxylation process. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 601, 117935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Lei, S.; Du, K. High-surface-area interconnected macroporous nanofibrous cellulose microspheres: A versatile platform for large capacity and high-throughput protein separation. Cellulose 2021, 28, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tanioka, A.; Matsumoto, H. De Novo Ion-Exchange Membranes Based on Nanofibers. Membranes 2021, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, J.; Fan, J.; Pourdeyhimi, B.; Boi, C.; Carbonell, R.G. Advances in high-throughput, high-capacity nonwoven membranes for chromatography in downstream processing: A review. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 2300–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabaghian, Z.; Pakkaner, E.; Kong, L.; Yang, X. A review on chromatographic membranes for antibody purification: Factors affecting binding capacity and guidelines for membrane design. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 357, 130147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, H.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Salahi, E.; Tayebifard, A.; Rahimipour, M.R.; Keyanpour-Rad, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospun nylon 6/zinc doped hydroxyapatite membrane for protein separation: Mechanism of fouling and blocking model. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 59, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Greiner, A. On the way to clean and safe electrospinning—Green electrospinning: Emulsion and suspension electrospinning. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2011, 22, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Wang, X.; Fu, Q.; Si, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, X.; Sun, G.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. A versatile method for fabricating ion-exchange hydrogel nanofibrous membranes with superb biomolecule adsorption and separation properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 506, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafi, M.; Chery, J.; Frey, M.M. Functionalized Electrospun Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Nanofibrous Membranes with Poly(Methyl Vinyl Ether-Alt-Maleic Anhydride) for Protein Adsorption. Materials 2018, 11, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Kumar, B.; Lu, J. Handbook of Fibrous Materials, 2 Volumes: Volume 1: Production and Characterization/Volume 2: Applications in Energy, Environmental Science and Healthcare; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; An, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z. Preparation of pH-controllable nanofibrous membrane functionalized with lysine for selective adsorption of protein. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 531, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Attabi, R.; Merenda, A.; Hsia, T.; Sriramoju, B.; Dumée, L.F.; Thang, S.H.; Pham, H.; Yang, X.; Kong, L. Morphology engineering of nanofibrous poly(acrylonitrile)-based strong anion exchange membranes for enhanced protein adsorption and recovery. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 65, 105750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-T.; Wickramasinghe, S.R.; Qian, X. Electrospun Weak Anion-Exchange Fibrous Membranes for Protein Purification. Membranes 2020, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Ju, J.; Wang, S.; Hao, L.; Sui, K.; Xia, Y.; Tan, Y. Seaweed-Derived Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes for Ultrahigh Protein Adsorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1905610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dods, S.R.; Hardick, O.; Stevens, B.; Bracewell, D.G. Fabricating electrospun cellulose nanofibre adsorbents for ion-exchange chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1376, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fu, Q.; Wang, X.; Si, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, B. In situ cross-linked and highly carboxylated poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibrous membranes for efficient adsorption of proteins. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 7281–7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, Q.; Si, Y.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Highly Carbonylated Cellulose Nanofibrous Membranes Utilizing Maleic Anhydride Grafting for Efficient Lysozyme Adsorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 15658–15666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Huang, J.; Pakkaner, E.; Wagemans, J.; Eyley, S.; Thielemans, W.; Gijsbers, R.; Smet, M.; Yang, X. Tailoring stimuli-responsive PVDF-based copolymer membrane with engineered pore structure for efficient antibody purification. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, J.; Yao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, J. Electrospun poly(styrene-co-maleic anhydride) nanofibrous membrane: A versatile platform for mixed mode membrane adsorbers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 484, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Fieg, G.; Keil, F.J.; Jakobtorweihen, S. Adsorption of Proteins onto Ion-Exchange Chromatographic Media: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 16049–16058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Lenhoff, A.M. Electrostatic Contributions to Protein Retention in Ion-Exchange Chromatography. 1. Cytochrome c Variants. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 6743–6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, H.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Salahi, E.; Tayebifard, A.; Keyanpour-Rad, M.; Rahimipour, M.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Protein adsorption on electrospun zinc doped hydroxyapatite containing nylon 6 membrane: Kinetics and isotherm. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 443, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Peng, R.; Chen, X. Hydrophobic interaction membrane chromatography for bioseparation and responsive polymer ligands involved. Front. Mater. Sci. 2017, 11, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, M.; Verdes, D.; Seeger, S. Understanding protein adsorption phenomena at solid surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 162, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahirel, V.; Jardat, M. Effective interactions between charged nanoparticles in water: What is left from the DLVO theory? Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 15, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umatheva, U. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations of Membrane and Resin-Based Chromatography. Doctoral Dissertation, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lemma, S.M.; Boi, C.; Carbonell, R.G. Nonwoven Ion-Exchange Membranes with High Protein Binding Capacity for Bioseparations. Membranes 2021, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Si, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Elaborate design of ethylene vinyl alcohol (EVAL) nanofiber-based chromatographic media for highly efficient adsorption and extraction of proteins. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 555, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Boi, C.; Lemma, S.M.; Lavoie, J.; Carbonell, R.G. Iminodiacetic Acid (IDA) Cation-Exchange Nonwoven Membranes for Efficient Capture of Antibodies and Antibody Fragments. Membranes 2021, 11, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, S.; Schneiderman, S.; Crandall, C.; Fong, H.; Menkhaus, T.J. Synthesis of Cellulose-graft-Polypropionic Acid Nanofiber Cation-Exchange Membrane Adsorbers for High-Efficiency Separations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 41055–41065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dismer, F.; Hubbuch, J.; Ulbricht, M. Detailed analysis of membrane adsorber pore structure and protein binding by advanced microscopy. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tao, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Wan, Y.; Chen, G. The Effect of Pore Channel Structure Uniformity on the Performance of a Membrane Adsorber Determined by Flow Distribution Analysis Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Processes 2025, 13, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahianbijan, F.; Giglia, S.; Carbrello, C.; Zydney, A.L. Quantitative analysis of internal flow distribution and pore interconnectivity within asymmetric virus filtration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 595, 117578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoy Altinkaya, S. A review on microfiltration membranes: Fabrication, physical morphology, and fouling characterization techniques. Front. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lu, J.; Guo, L. Fabrication of highly carboxylated thermoplastic nanofibrous membranes for efficient absorption and separation of protein. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 665, 131203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasim, M.; Khan, M.H.; Bibi, N.S.; Fernandez-Lahore, M. Understanding the interaction of proteins to ion exchange chromatographic supports: A surface energetics approach. Biotechnol. Prog. 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samari-Kermani, M.; Jafari, S.; Rahnama, M.; Raoof, A. Ionic strength and zeta potential effects on colloid transport and retention processes. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 42, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasim, M.; Bibi, N.S.; Vennapusa, R.R.; Fernandez-Lahore, M. Extended DLVO calculations expose the role of the structural nature of the adsorbent beads during chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 35, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persico, M.; Mikhaylin, S.; Doyen, A.; Firdaous, L.; Hammami, R.; Chevalier, M.; Flahaut, C.; Dhulster, P.; Bazinet, L. Formation of peptide layers and adsorption mechanisms on a negatively charged cation-exchange membrane. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 508, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firkowska-Boden, I.; Zhang, X.; Jandt, K.D. Controlling Protein Adsorption through Nanostructured Polymeric Surfaces. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1700995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachimska, B.; Pajor, A. Physico-chemical characterization of bovine serum albumin in solution and as deposited on surfaces. Bioelectrochemistry 2012, 87, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, S.A.; Evans, E.; Benavidez, T.E.; Garcia, C.D. Protein adsorption onto nanomaterials for the development of biosensors and analytical devices: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 872, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Poncet-Legrand, C.; Staunton, S.; Quiquampoix, H. pH-Dependent Changes in Structural Stabilities of Bt Cry1Ac Toxin and Contrasting Model Proteins following Adsorption on Montmorillonite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5693–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-X.; Pang, X. Electrostatic Interactions in Protein Structure, Folding, Binding, and Condensation. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1691–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xin, Q.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Ding, X. Protein adsorption and desorption behavior of a pH-responsive membrane based on ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 21398–21405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Yin, Z. The Role of Surface Properties on Protein Aggregation Behavior in Aqueous Solution of Different pH Values. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wu, Z.; Wangb, Y.; Ding, L.; Wang, Y. Role of pH-induced structural change in protein aggregation in foam fractionation of bovine serum albumin. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 9, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassel, K.J.; Moresoli, C. Role of pH and Ionic strength on weak cation exchange macroporous Hydrogel membranes and IgG capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 498, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushko, M.L.; Shluger, A.L. DLVO theory for like-charged polyelectrolyte and surface interactions. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2007, 27, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, E. Recent Developments in the Methods and Applications of Electrostatic Theory. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 2267–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, H.T.; Perrot, C.; Panneton, R. Influence of Porosity, Fiber Radius and Fiber Orientation on the Transport and Acoustic Properties of Random Fiber Structures. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2017, 103, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.A. Computational models for studying physical instabilities in high concentration biotherapeutic formulations. mAbs 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J. Multiscale modeling and simulations of protein adsorption: Progresses and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 41, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Fieg, G.; Jakobtorweihen, S. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of a Binary Protein Mixture Adsorption onto Ion-Exchange Adsorbent. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 2794–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.A.; Jayaraman, A. Molecular Modeling and Simulations of Peptide–Polymer Conjugates. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2020, 11, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, D.A.; Razul, M.S.G. Computer simulation techniques for food science and engineering: Simulating atomic scale and coarse-grained models. Food Struct. 2014, 1, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; He, Z.; Quan, X.; Sun, D.; Miao, Z.; Yu, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, J. Molecular simulations of charged complex fluids: A review. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glotzer, S.C.; Paul, W. Molecular and Mesoscale Simulation Methods for Polymer Materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2002, 32, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, Z.G.; Mao, W.; Alexeev, A. Mesoscale modeling: Solving complex flows in biology and biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Sundén, B.; Yuan, J. Analysis of multi-phase transport phenomena with catalyst reactions in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells—A review. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 7899–7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkas, G.; Euston, S.R. Molecular simulation of protein adsorption and conformation at gas-liquid, liquid–liquid and solid–liquid interfaces. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournois, M.; Mathé, S.; André, I.; Esque, J.; Fernández, M.A. Surface charge distribution: A key parameter for understanding protein behavior in chromatographic processes. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1648, 462151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiblinger, N.; Hahn, R.; Carta, G. Efficient calculation of the equilibrium composition in multicomponent batch adsorption with the steric mass action model. Adsorption 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, M.d.S.; Santos, M.S.; Lima, E.R.d.A.; Tavares, F.W.; Barreto, A.G.B. A modified Poisson-Boltzmann equation applied to protein adsorption. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1531, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, R.; Lingg, N. Chapter 21—Separation of proteins by ion-exchange chromatography. In Ion-Exchange Chromatography and Related Techniques; Nesterenko, P.N., Poole, C.F., Sun, Y., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 435–460. [Google Scholar]

- Briskot, T.; Hahn, T.; Huuk, T.; Hubbuch, J. Protein adsorption on ion exchange adsorbers: A comparison of a stoichiometric and non-stoichiometric modeling approach. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1653, 462397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babi, D.K.; Griesbach, J.; Hunt, S.; Insaidoo, F.; Roush, D.; Todd, R.; Staby, A.; Welsh, J.; Wittkopp, F. Opportunities and challenges for model utilization in the biopharmaceutical industry: Current versus future state. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2022, 36, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boztepe, I.; Yang, X.; Zhao, S.; Kong, L. Module Design for Membrane Chromatography Applications in Downstream Bioprocessing: Flow Distribution Matters. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 21733–21746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, K.; Shirzadi, M.; Fukasawa, T.; Fukui, K.; Ishigami, T. Prediction of fluid-particle dynamics and performance in fibrous filters obtained from X-ray CT using convolutional neural network and discrete phase model. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, J.; Salehi, F.; Sheikholeslami, M.; Masoudi, M.; Lee, A. Optimization of nanofluid heat transfer in a microchannel heat sink with multiple synthetic jets based on CFD-DPM and MLA. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2021, 167, 107008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shikhov, I.; Arns, C. Mechanisms of Pore-Clogging Using a High-Resolution CFD-DEM Colloid Transport Model. Transp. Porous Media 2024, 151, 831–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S.B.; Ha, E.-S.; Kim, M.-S.; Jeong, S.H.; Hwang, S.-J.; Choi, D.H. Application of the Discrete Element Method for Manufacturing Process Simulation in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaresan, S.; Ozel, A.; Kolehmainen, J. Toward Constitutive Models for Momentum, Species, and Energy Transport in Gas–Particle Flows. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2018, 9, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar, A.; Ramachandran, R. CFD–DEM–PBM coupled model development and validation of a 3D top-spray fluidized bed wet granulation process. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2019, 125, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodołażski, A. Metaheurystic optimization of CFD–multiphase population balance and biokinetics aeration stirrer tank bioreactor of sludge flocs for scale-up study with bio(de/re)flocculation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 184, 108477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Franks, G.V.; Goudeli, E. Aggregation and breakage dynamics of alumina particles under shear by coupled Computational Fluid Dynamics—Discrete Element Method. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 661, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.a.; Diao, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chu, M.; Han, K.; Shen, H. Study on turbulent aggregation dynamics in the process of fine particles capture by single fibers. Part. Sci. Technol. 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gautam, S.; Atri, S.; Tafreshi, H.V.; Pourdeyhimi, B. The impact of particle deposition on collection efficiency of electret fibers. J. Aerosol Sci 2024, 181, 106426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briskot, T.; Hahn, T.; Huuk, T.; Hubbuch, J. Adsorption of colloidal proteins in ion-exchange chromatography under consideration of charge regulation. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1611, 460608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohaus, J.; Perez, Y.M.; Wessling, M. What are the microscopic events of colloidal membrane fouling? J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 553, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agmo Hernández, V. An overview of surface forces and the DLVO theory. ChemTexts 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahian, O.; Kolsi, L.; Amani, M.; Estellé, P.; Ahmadi, G.; Kleinstreuer, C.; Marshall, J.S.; Siavashi, M.; Taylor, R.A.; Niazmand, H.; et al. Recent advances in modeling and simulation of nanofluid flows-Part I: Fundamentals and theory. Phys. Rep. 2019, 790, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicane, G. Colloidal Model of Lysozyme Aqueous Solutions: A Computer Simulation and Theoretical Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegh, H.; Sahay, R.; Soni, S. Protein–polymer interaction: Transfer loading at interfacial region of PES-based membrane and BSA. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasim, M.; Hidayatullah Khan, M.; Bibi, N.S.; Zaman Khan, N. Protein adsorption onto monoliths: A surface energetics study. Eng. Life Sci. 2018, 18, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapikouni, T.S.; Missirlis, Y.F. Protein–material interactions: From micro-to-nano scale. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2008, 152, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, A.; Cui, H.; Zhou, B.; Qiao, J.; Wei, J.; Li, X. Protein language model empowered the robust ASR-driven PET hydrolase featured with two PET binding motifs. Green Carbon 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S.A.; Sasidharan, S.; Kim, H.; Gomez-Flores, A.; Li, T.; Shen, C. Colloid Interaction Energies for Surfaces with Steric Effects and Incompressible and/or Compressible Roughness. Langmuir 2021, 37, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiura, A.; Dutta, C.; Leung, W.; Zepeda O, J.; Terlier, T.; Landes, C.F. The competing influence of surface roughness, hydrophobicity, and electrostatics on protein dynamics on a self-assembled monolayer. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollon, G.; Quacquarelli, A.; Andò, E.; Viggiani, G. Can friction replace roughness in the numerical simulation of granular materials? Granul. Matter 2020, 22, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akampumuza, O.; Xu, H.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, H.; Quan, Z.; Qin, X. Analyzing the effect of nanofiber orientation on membrane filtration properties with the progressive increase in its thickness: A numerical and experimental approach. Text. Res. J. 2020, 90, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Sansare, S.; Nagarajan, V.; Chaudhuri, B. Discrete Element Modeling (DEM) based investigation of tribocharging in the pharmaceutical powders during hopper discharge. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 596, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyegbile, B.; Ay, P.; Narra, S. Flocculation kinetics and hydrodynamic interactions in natural and engineered flow systems: A review. Environ. Eng. Res. 2016, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, J.L.; Webster, T.J. Protein Interactions at Material Surfaces; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Barberi, J.; Spriano, S. Titanium and Protein Adsorption: An Overview of Mechanisms and Effects of Surface Features. Materials 2021, 14, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Keeling, R.; Tracka, M.; Van Der Walle, C.F.; Uddin, S.; Warwicker, J.; Curtis, R. The Role of Electrostatics in Protein–Protein Interactions of a Monoclonal Antibody. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 2475–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Roche, A.; van der Walle, C.F.; Uddin, S.; Du, J.; Warwicker, J.; Pluen, A.; Curtis, R. Determination of Protein–Protein Interactions in a Mixture of Two Monoclonal Antibodies. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 4775–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Srivastava, P.; Rathore, A.S.; Chokshi, P. Population balance modelling of aggregation of monoclonal antibody based therapeutic proteins. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 216, 115479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Way, A.; Wang, C. Enhancing aggregate reduction using anion exchange hybrid filter in an immunocytokine diabody fusion protein purification process. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1739, 465526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachy, V.; Kalyuzhnyi, Y.V.; Hribar-Lee, B.; Dill, K.A. Protein Association in Solution: Statistical Mechanical Modeling. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusara, S.; Yamin, P.; Wenzel, W.; Krstić, M.; Kozlowska, M. A coarse-grained xDLVO model for colloidal protein–protein interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 12780–12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Pattanayek, S.K. Effect of surface energy of solid surfaces on the micro- and macroscopic properties of adsorbed BSA and lysozyme. Biophys. Chem. 2017, 226, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subeshan, B.; Atayo, A.; Asmatulu, E. Machine learning applications for electrospun nanofibers: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 14095–14140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangayach, R.; Jeong, N.; Demirel, E.; Uzal, N.; Fung, V.; Chen, Y. Machine Learning-Aided Inverse Design and Discovery of Novel Polymeric Materials for Membrane Separation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Separation Type | Method |

|---|---|

| Ion exchange | Reversible adsorption of a charged protein to ion-exchange matrices containing oppositely charged covalently attached side groups [4] |

| Hydrophobic interaction | Adsorbents, which have covalently attached hydrophobic groups Hydrophilic region exposure is promoted by decreased ionic strength [12] |

| Affinity | Specific interaction between the immobilised ligand and the binding site on the target molecule [13] Selective and efficient target molecule capturing [14] Most selective chromatography types among others [12] |

| Mixed-mode | Selective protein adsorption by the combination of several separation methods and membrane adsorbents [8] |

| Ref. | Nanofibrous Membrane | Fibre Diameter (df) (nm) | Water Contact Angle (WCA) (o) | Mean Pore Size (µm) | Specific Surface Area (SSA) (m2/g) | Target Protein | pH | Initial Concentration (mg/mL) | Binding Capacity (mg/g or mg/mL *) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | PAN-pAQ | 353 ± 69–673 ± 36 | 115 ± 5–132 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.1–1.7 ± 0.2 | 4.4–9.3 | BSA | 7.5 | - | 98 ± 8–166 ± 2 (SBC) |

| [36] | PSf-GMA-DEA PAN-GMA-DEA | 2500 ± 460 (PSf) 150–340 (PAN) | 128 ± 4.8 (PSf) 73.1 ± 3.5 (PAN) | - | - | BSA | 7.0 | 0.5–3 | 201.3 ± 4.8 * (PSf) 87.2 ± 2.6 * (PAN) (DBC) 260 * (PSf) 100 *(PAN) (SBC) |

| [16] | EVOH-CCA | 562 | 120 | - | 2.52 | Lysozyme | 4–10 | 1 | 250 (DBC) |

| [37] | SA-PEO | 150 | - | 0.3–0.6 | 13.56 (g/m2) | Lysozyme | 3.18 | 0.4–2.0 | 805 (DBC) 1235 (SBC) |

| [38] | CA-DEAE and CA-COO | 500 | - | - | - | Lysozyme BSA | 8.0/BSA5.5/Lysozyme | 2.0 | COO-27 * lysozyme (DBC) & DEAE-20 * BSA (DBC) |

| [39] | PVA-MAH | 226-(30% PVA) 284-(5% PVA) | 45 | 0.002–0.064 | 3.2–3.5 (g/m2) | Lysozyme | 6.0 | 0.1–1.2 | 159 (DBC) |

| [40] | CMA | 267 | 124 | 0.65 | 3.28 (g/m2) | Lysozyme | 4–8 | 1 | 160 (SBC) 118 (DBC) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boztepe, I.; Zhao, S.; Yang, X.; Kong, L. Toward Rational Design of Ion-Exchange Nanofiber Membranes: Meso-Scale Computational Approaches. Membranes 2026, 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010005

Boztepe I, Zhao S, Yang X, Kong L. Toward Rational Design of Ion-Exchange Nanofiber Membranes: Meso-Scale Computational Approaches. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoztepe, Inci, Shuaifei Zhao, Xing Yang, and Lingxue Kong. 2026. "Toward Rational Design of Ion-Exchange Nanofiber Membranes: Meso-Scale Computational Approaches" Membranes 16, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010005

APA StyleBoztepe, I., Zhao, S., Yang, X., & Kong, L. (2026). Toward Rational Design of Ion-Exchange Nanofiber Membranes: Meso-Scale Computational Approaches. Membranes, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010005