Development of High-Performance Catalytic Ceramic Membrane Microchannel Reactor for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Methanol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

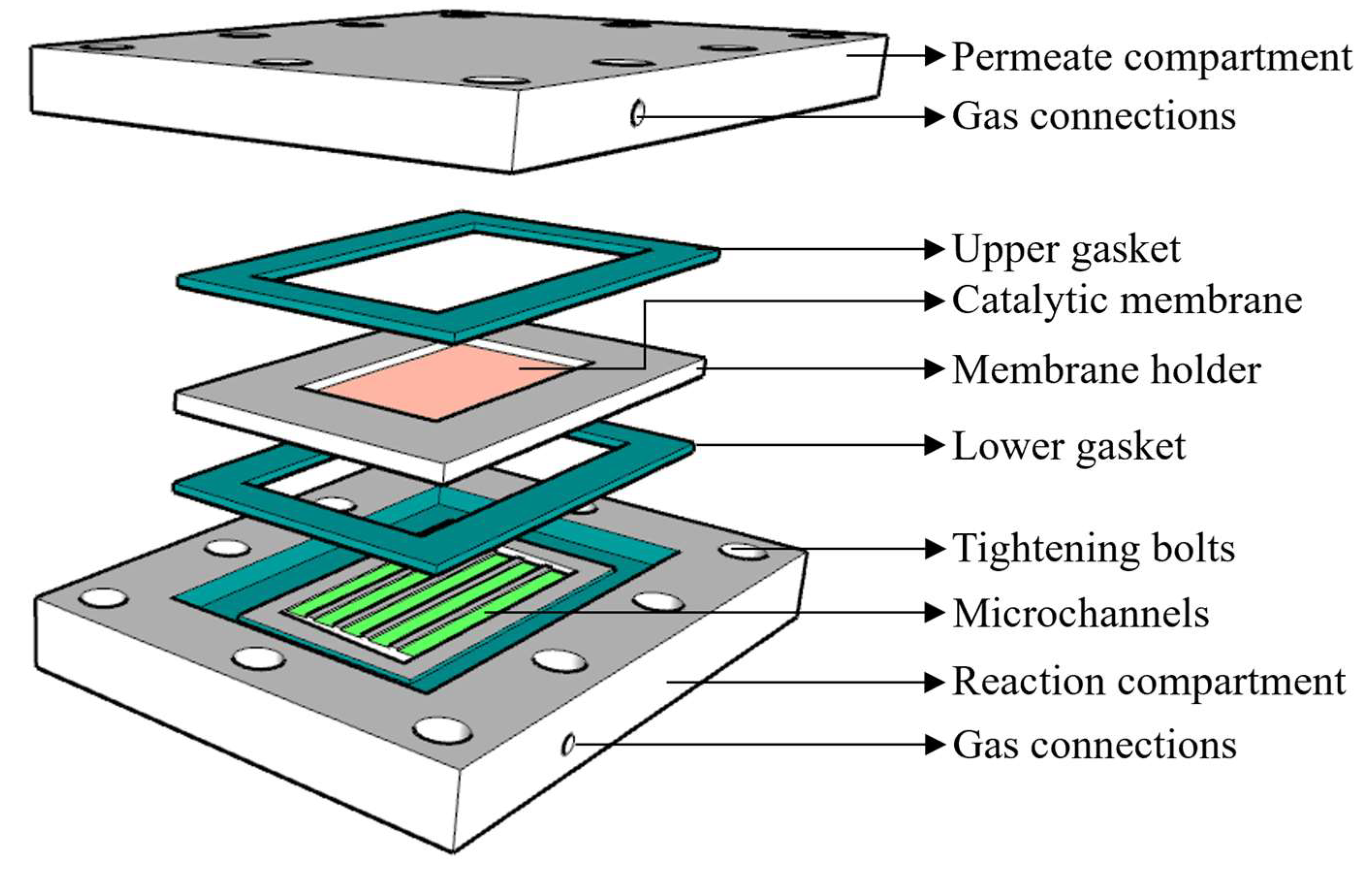

2.1. Ceramic Membrane Microchannel Reactor

2.1.1. Reactor Module

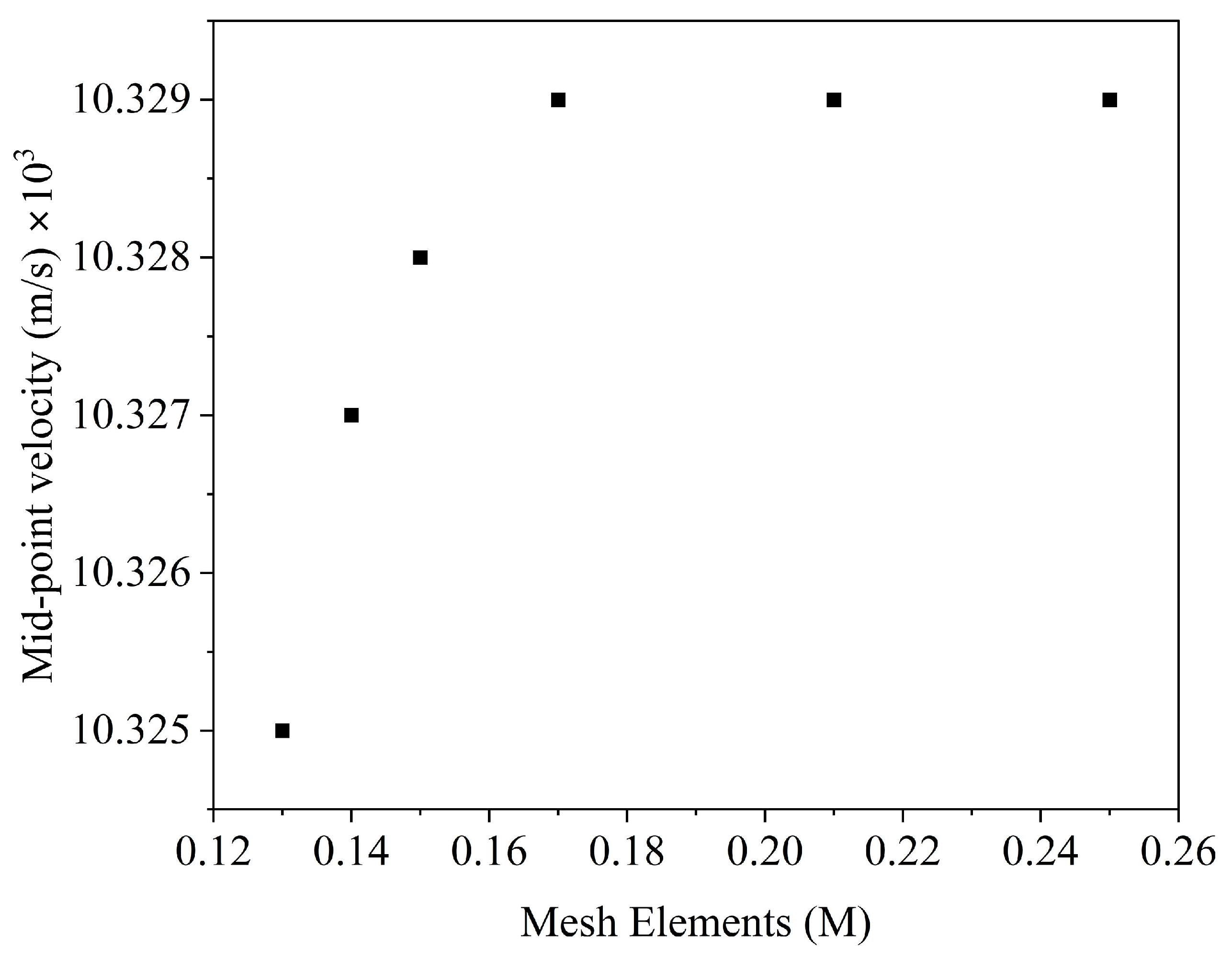

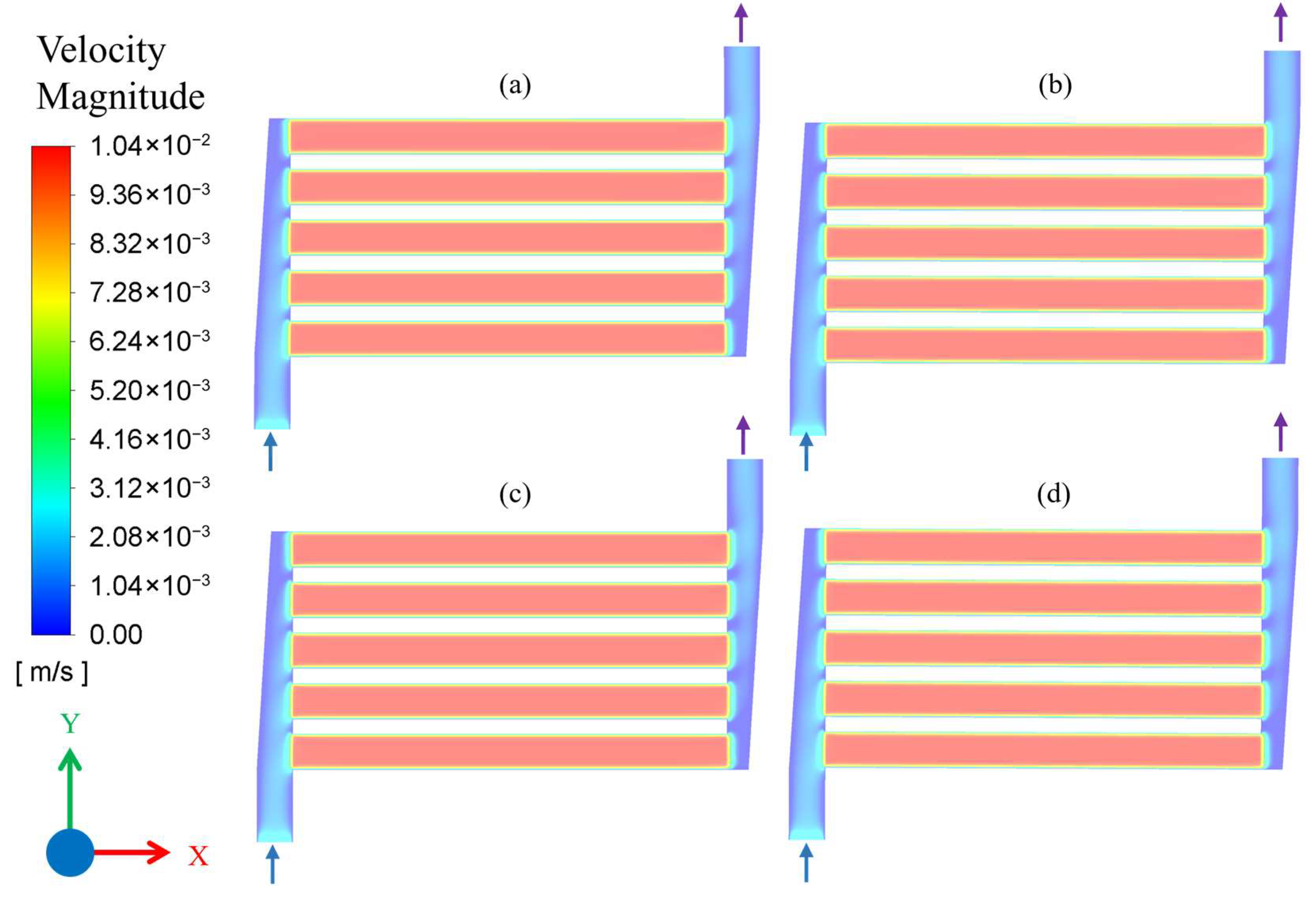

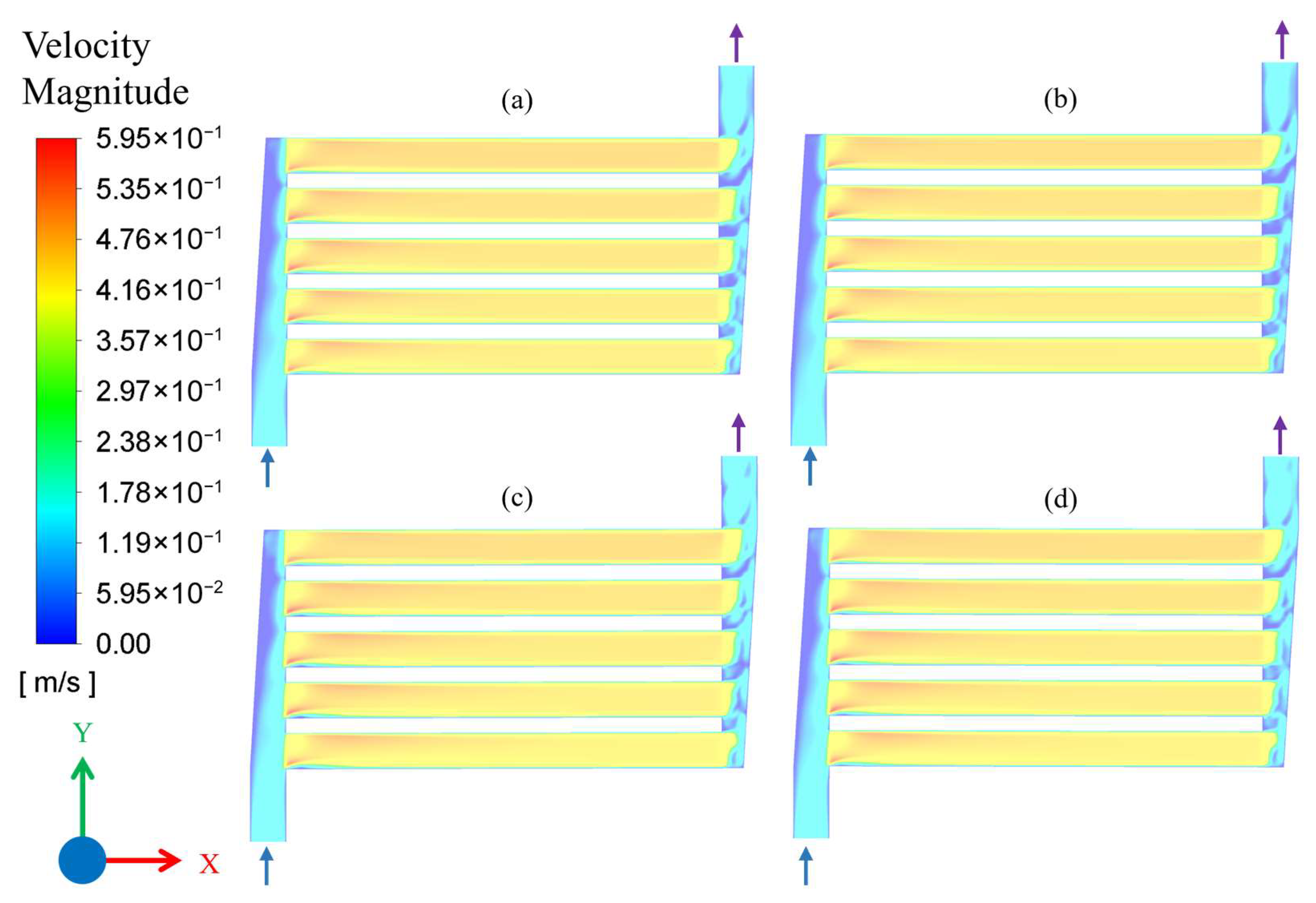

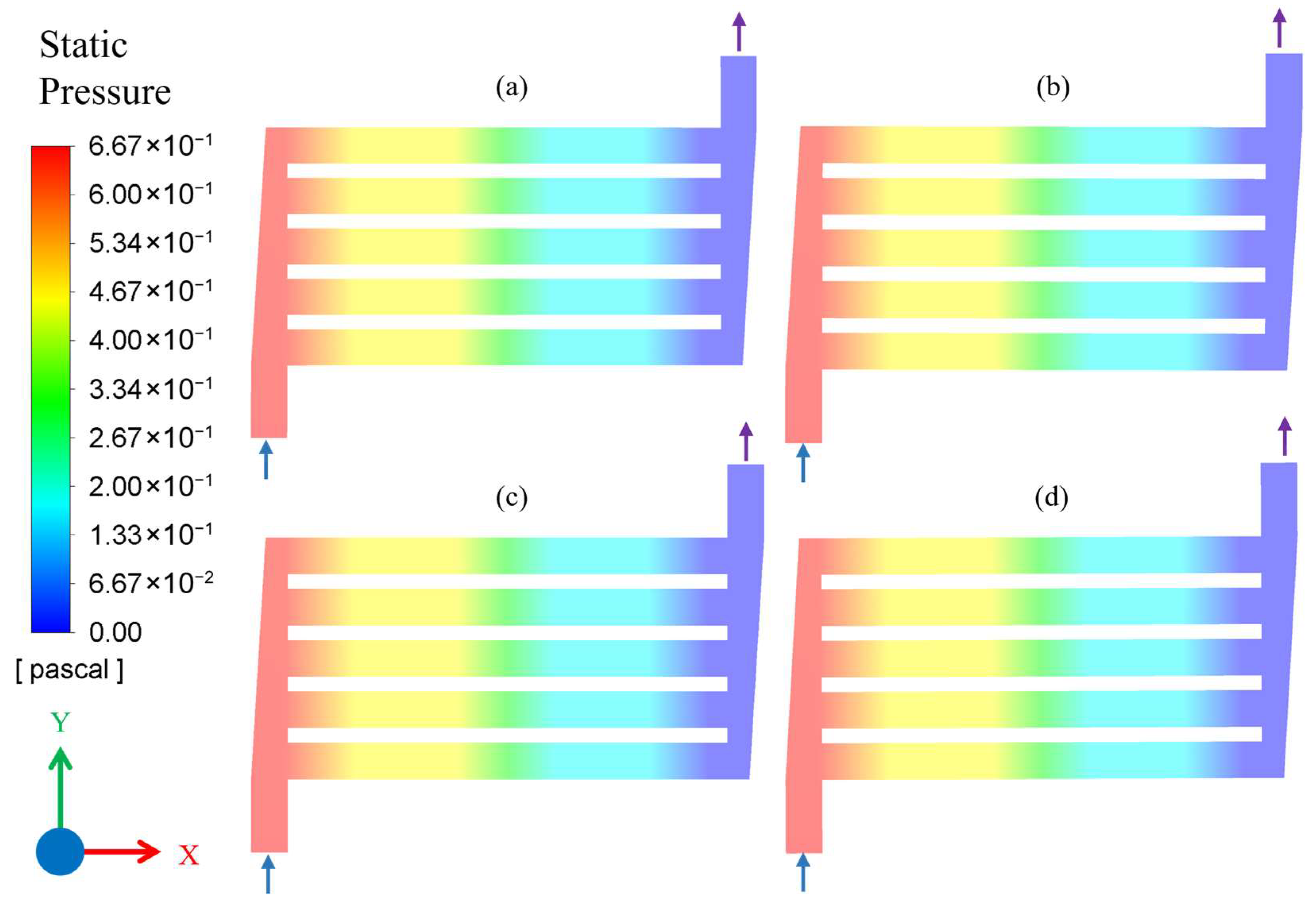

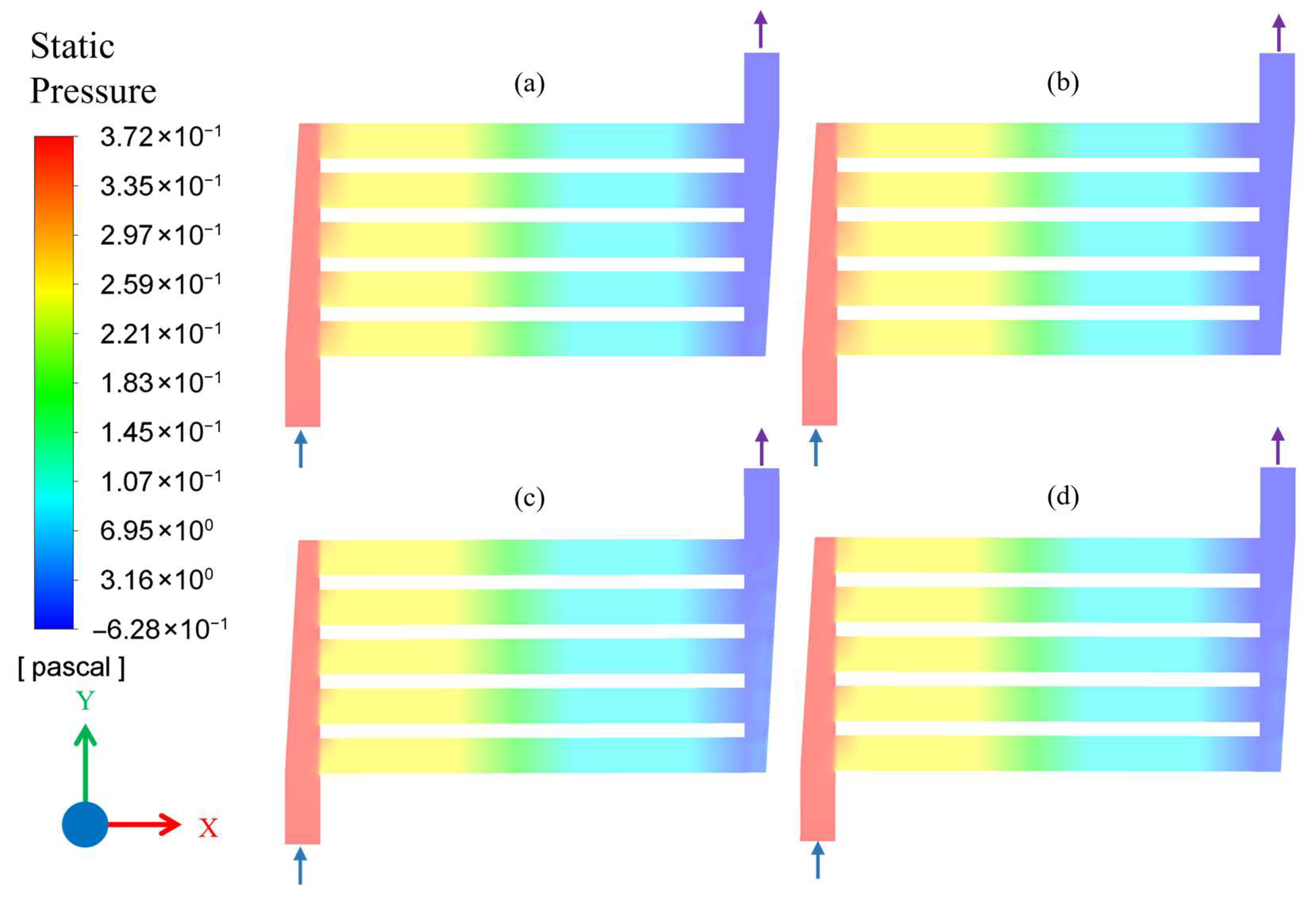

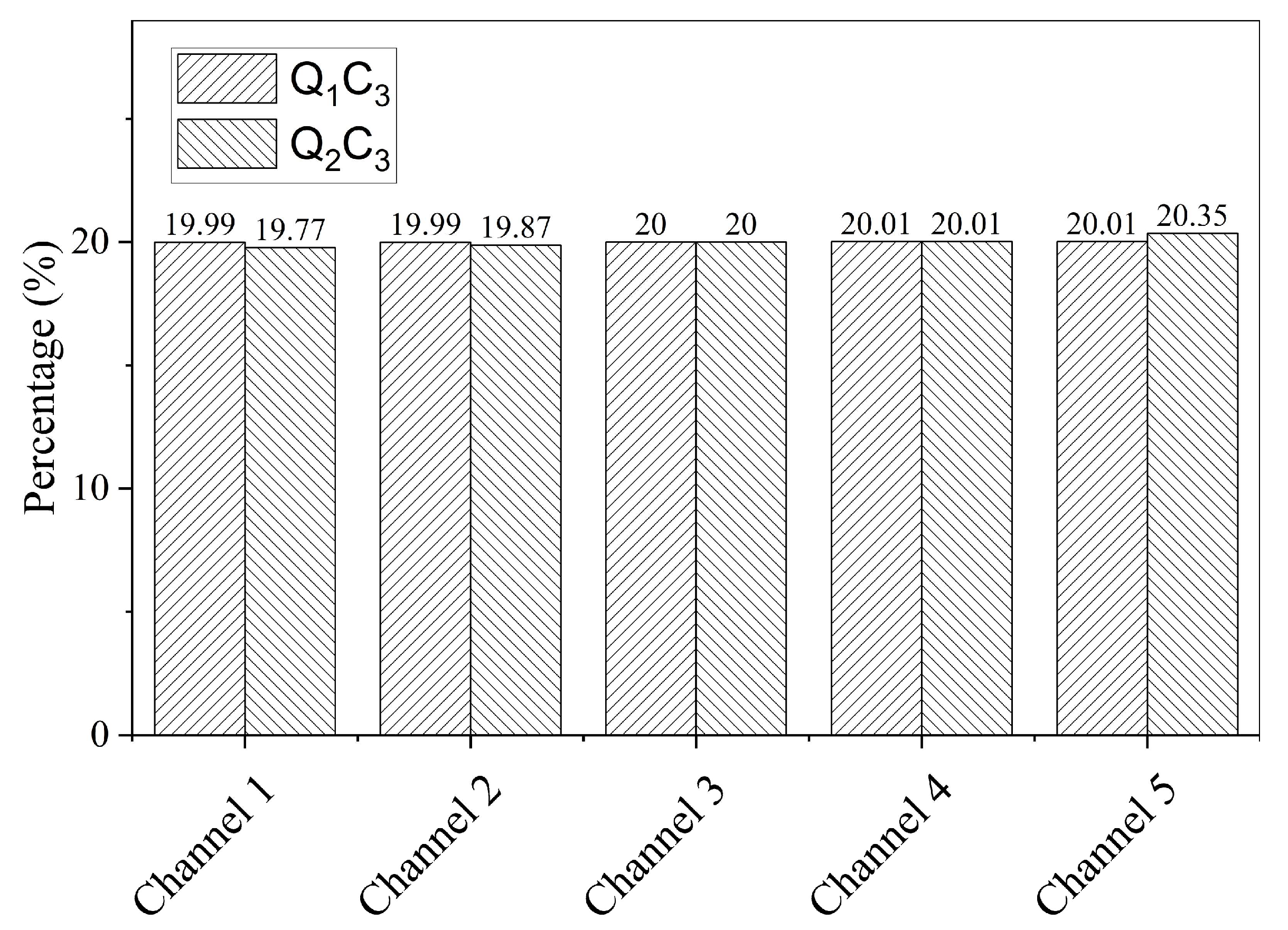

2.1.2. CFD Simulations

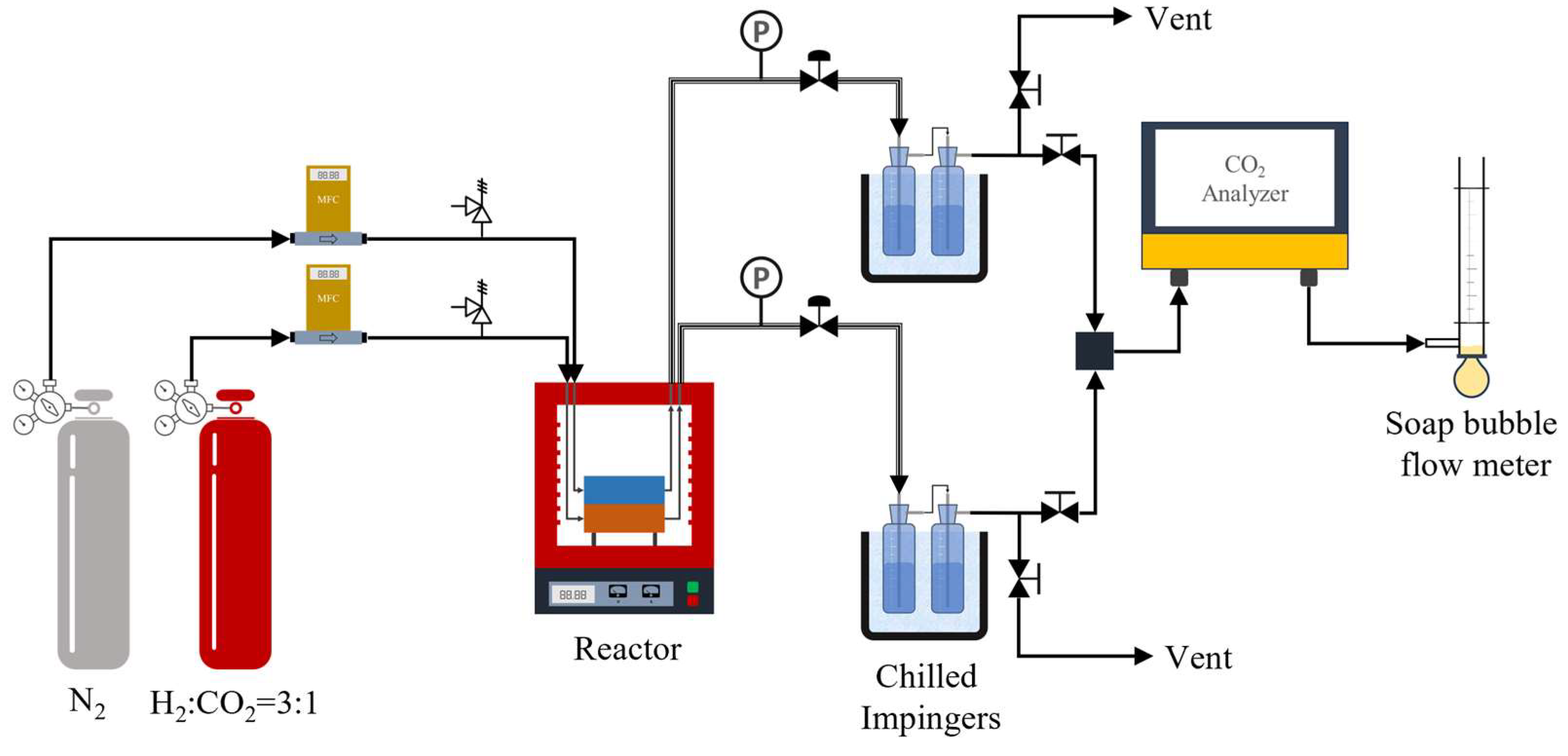

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.2.1. Materials

2.2.2. Synthesis of LTA Zeolite Membrane

2.2.3. Synthesis of Catalyst and Catalytic Membrane

2.2.4. Performance Test

2.3. Membrane and Catalyst Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of CFD Simulations

3.2. Results of Synthesized LTA Zeolite Membrane

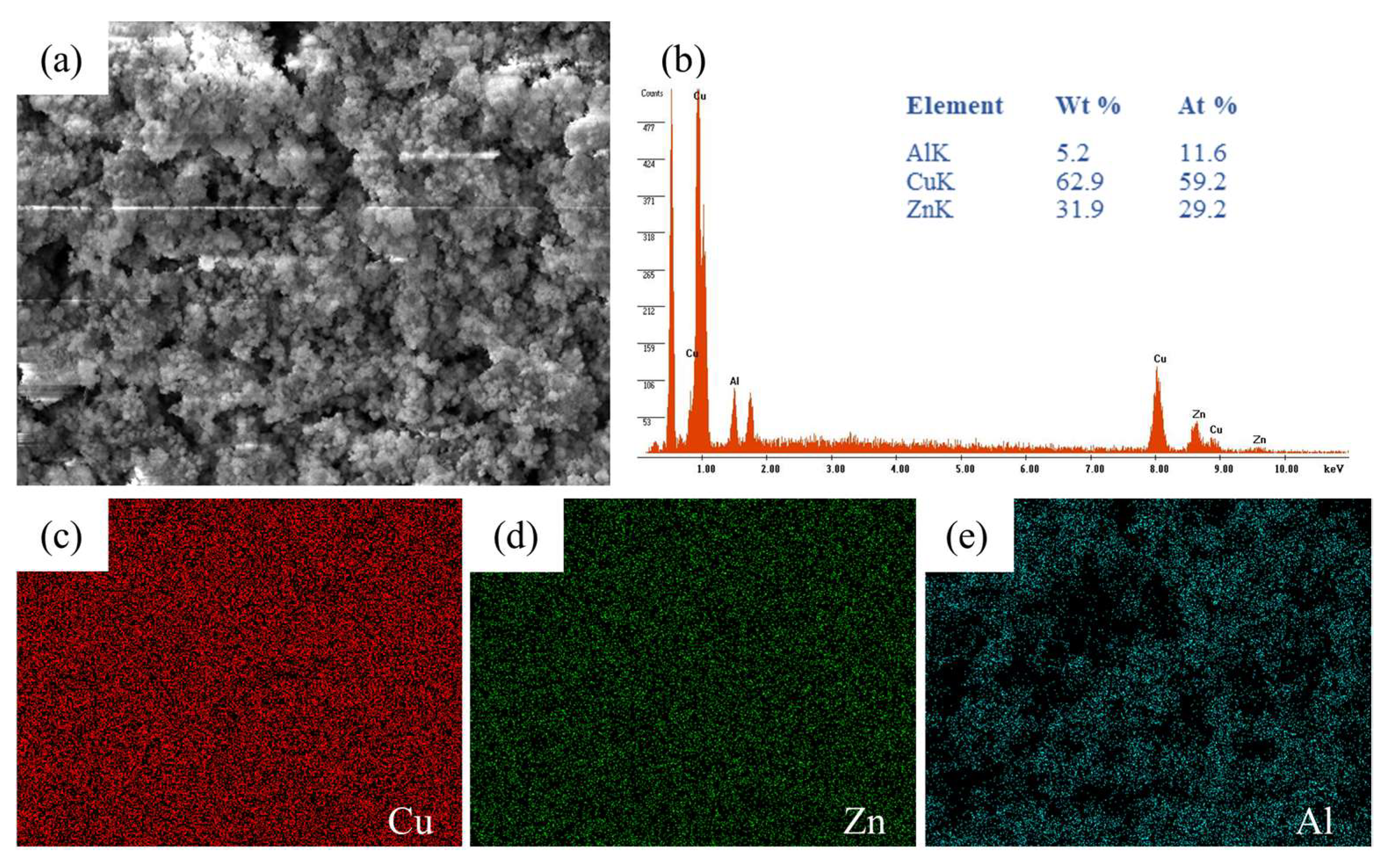

3.3. Catalyst and Catalytic Membrane

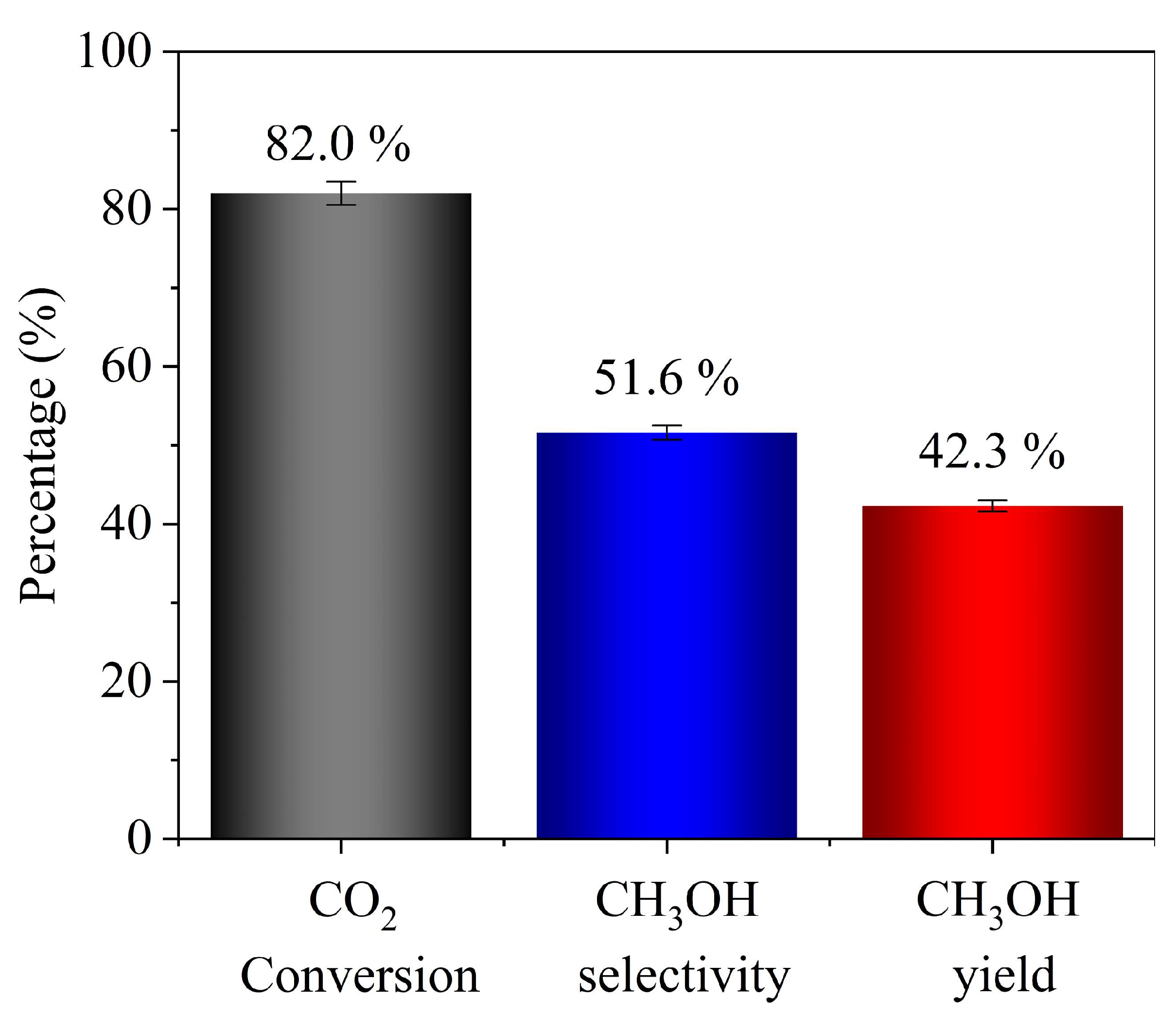

3.4. Performance Test

| Reactor Type | Catalyst | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (MPa) | CO2 Conversion | CH3OH Selectivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium conditions | NA * | 250 | 5.0 | 27 | 68 | [35] |

| Traditional packed bed reactor | Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 | 250 | 3.0 | 8.5 | 33 | [35] |

| Packed bed tubular membrane reactor | Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 | 256 | 2.0 | 16.5 | 37.9 | [38] |

| Catalytic membrane tubular reactor | Cu-ZnO-Al2O3-ZrO2 | 220 260 | 3.0 3.0 | 26.5 36.1 | 93.2 100 | [14] |

| Catalytic membrane tubular reactor | Cu/Zn-BTC | 250 | 3.0 | 49.1 | 93.4 | [16] |

| Packed bed hollow-fiber membrane reactor | Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 | 220 250 | 3.5 3.5 | 57.2 61.4 | 67 45 | [15] |

| Catalytic membrane microchannel reactor | Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 | 220 | 3.0 | 82 | 51.6 | This work |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, B.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Xue, J.; Andrew, R.; Feng, K.; Qi, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Developing countries’ responsibilities for CO2 emissions in value chains are larger and growing faster than those of developed countries. One Earth 2023, 6, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Kharas, H.; McArthur, J.W. Developing Countries Are Key to Climate Action. 2023. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/developing-countries-are-key-to-climate-action/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- European Commission. 2030 Climate Targets. 2023. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2030-climate-targets_en (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Behera, P.; Haldar, A.; Sethi, N. Achieving carbon neutrality target in the emerging economies: Role of renewable energy and green technology. Gondwana Res. 2023, 121, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris agreement. In Proceedings of the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) to United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Paris, France, 12 December 2015.

- UNFCC. COP29 UN Climate Conference Agrees to Triple Finance to Developing Countries, Protecting Lives and Livelihoods. 2024. Available online: https://unfccc.int/news/cop29-un-climate-conference-agrees-to-triple-finance-to-developing-countries-protecting-lives-and (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Olah, G.A. Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2636–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olah, G.A.; Goeppert, A.; Prakash, G.K.S. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol and Dimethyl Ether: From Greenhouse Gas to Renewable, Environmentally Carbon Neutral Fuels and Synthetic Hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeppert, A.; Czaun, M.; Jones, J.-P.; Prakash, G.K.S.; Olah, G.A. Recycling of carbon dioxide to methanol and derived products—Closing the loop. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7995–8048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Breyer, C. Global production potential of green methanol based on variable renewable electricity. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 3503–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R. Renewable Methanol as an Agent for the Decarbonization of Maritime Logistic Systems: A Review. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollai, S.; Porcu, A.; Tola, V.; Ferrara, F. Pettinau, Renewable methanol production from green hydrogen and captured CO2: A techno-economic assessment. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 68, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgun, I.; Dincer, I. Development of an integrated energy system with CO2 capture and utilization in an industrial setting for clean hydrogen and methanol. Energy 2025, 320, 135106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Li, Y.; Wei, W.; Jiang, J.; Caro, J.; Huang, A. Highly Selective CO2 Conversion to Methanol in a Bifunctional Zeolite Catalytic Membrane Reactor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 18289–18294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, C.; Ren, S.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, F.; Liang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Yu, M. Na+ -gated water-conducting nanochannels for boosting CO2 conversion to liquid fuels. Science 2020, 367, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Huang, A. Synthesis of a Cu/Zn-BTC@LTA derivatived Cu–ZnO@LTA membrane reactor for CO2 hydrogenation. J. Memb. Sci. 2022, 662, 121010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshimo, M.; Liu, B.; Lee, H.R.; Yogo, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Shigaki, N.; Mogi, Y.; Kita, H.; Nakao, S. Membrane Reactor for Methanol Synthesis Using Si-Rich LTA Zeolite Membrane. Membranes 2021, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Cao, E.; Ellis, P.; Constantinou, A.; Kuhn, S.; Gavriilidis, A. Development of a flat membrane microchannel packed-bed reactor for scalable aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol in flow. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 377, 120086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojang, A.A.; Wu, H.-S. Design, fundamental principles of fabrication and applications of microreactors. Processes 2020, 8, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, K.; Wong, K.Y.; Wong, K.H.; Chong, C.T.; Ng, J.-H. Enhancing biodiesel production: A review of microchannel reactor technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizualem, Y.D.; Nurie, A.G.; Nadew, T.T. A review on biodiesel micromixers: Types of micromixers, configurations, and flow patterns. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, H.; Xie, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Advanced stackable membrane microreactor for gas–liquid-solid reactions: Design, operation, and scale-up. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 504, 158798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Meng, X.; Xu, B.; Yang, J.; Li, S.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; et al. Synthesis of zeolite NaA membranes with high performance and high reproducibility on coarse macroporous supports. J. Memb. Sci. 2013, 444, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, T.; Bian, Z.; Lim, K.; Dewangan, N.; Haw, K.G.; Wang, Z.; Kawi, S. Low-cost and facile fabrication of defect-free water permeable membrane for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 133554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, G. Sweep Gas in a Membrane Reactor BT—Encyclopedia of Membranes; Drioli, E., Giorno, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauth, T.; Pielmaier, K.; Dieterich, V.; Wein, N.; Spliethoff, H.; Fendt, S. Design parameter optimization of a membrane reactor for methanol synthesis using a sophisticated CFD model. Energy Adv. 2025, 4, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakiliç, P.; Wang, X.; Kapteijn, F.; Nijmeijer, A.; Winnubst, L. Defect-free high-silica CHA zeolite membranes with high selectivity for light gas separation. J. Memb. Sci. 2019, 586, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, Z.; Fatemi, S.; Davoodpour, M. Comparative study of seeding methods; dip-coating, rubbing and EPD, in SAPO-34 thin film fabrication. Adv. Powder Technol. 2014, 25, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, R.; Luo, P.; Huang, W. Insight into the structural sensitivity of CuZnAl catalysts for CO hydrogenation to alcohols. Fuel 2022, 323, 124265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamsuwan, T.; Krutpijit, C.; Praserthdam, S.; Phatanasri, S.; Jongsomjit, B.; Praserthdam, P. Comparative study on the effect of different copper loading on catalytic behaviors and activity of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts toward CO and CO2 hydrogenation. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duma, Z.G.; Dyosiba, X.; Moma, J.; Langmi, H.W.; Louis, B.; Parkhomenko, K.; Musyoka, N.M. Thermocatalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 to Methanol Using Cu-ZnO Bimetallic Catalysts Supported on Metal–Organic Frameworks. Catalysts 2022, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián-Cabrera, I.; Granados, M.L.; Fierro, J.L.G. Structural reversibility of a ternary CuO-ZnO-Al2O3 ex hydrotalcite-containing material during wet Pd impregnation. Catal. Lett. 2002, 84, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurr, P.; Kasatkin, I.; Girgsdies, F.; Trunschke, A.; Schlögl, R.; Ressler, T. Microstructural characterization of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts for methanol steam reforming—A comparative study. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 348, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, N.D.; Jensen, A.D.; Christensen, J.M. The roles of CO and CO2 in high pressure methanol synthesis over Cu-based catalysts. J. Catal. 2021, 393, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makertiharta, I.G.B.N.; Dharmawijaya, P.T.; Wenten, I.G. Current progress on zeolite membrane reactor for CO2 hydrogenation. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1788, 40001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-X.; Yang, L.-Q.-Q.; Chi, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Li, X.-G.; He, Y.-L.; Reina, T.R.; Xiao, W.-D. CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol Over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 Catalyst: Kinetic Modeling Based on Either Single- or Dual-Active Site Mechanism. Catal. Lett. 2022, 152, 3110–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Hei, J.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Yin, X.; Meng, S. Influence of Cu/Al Ratio on the Performance of Carbon-Supported Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Catalysts 2023, 13, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, F.; Paturzo, L.; Basile, A. An experimental study of CO2 hydrogenation into methanol involving a zeolite membrane reactor. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2004, 43, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Simulation No. | Flow Rate (mL/min) | Pressure (MPa) | Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1C1 | 10 | 2.5 | 200 |

| Q1C2 | 10 | 2.5 | 260 |

| Q1C3 | 10 | 4.0 | 200 |

| Q1C4 | 10 | 4.0 | 260 |

| Q2C1 | 500 | 2.5 | 200 |

| Q2C2 | 500 | 2.5 | 260 |

| Q2C3 | 500 | 4.0 | 200 |

| Q2C4 | 500 | 4.0 | 260 |

| Component | Expected Composition (At. %) | XRF Composition (At. %) | EDS Composition (At. %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 60 | 64.1 | 59.2 |

| Zn | 30 | 34.4 | 29.2 |

| Al | 10 | 1.4 | 11.6 |

| Cu/Zn | 2 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ullah, A.; Hashim, N.A.; Rabuni, M.F.; Junaidi, M.U.M.; Ahmed, A.; Mohammed, M.G.; Siddique, M.S. Development of High-Performance Catalytic Ceramic Membrane Microchannel Reactor for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Methanol. Membranes 2026, 16, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010045

Ullah A, Hashim NA, Rabuni MF, Junaidi MUM, Ahmed A, Mohammed MG, Siddique MS. Development of High-Performance Catalytic Ceramic Membrane Microchannel Reactor for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Methanol. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleUllah, Aubaid, Nur Awanis Hashim, Mohamad Fairus Rabuni, Mohd Usman Mohd Junaidi, Ammar Ahmed, Mustapha Grema Mohammed, and Muhammed Sahal Siddique. 2026. "Development of High-Performance Catalytic Ceramic Membrane Microchannel Reactor for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Methanol" Membranes 16, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010045

APA StyleUllah, A., Hashim, N. A., Rabuni, M. F., Junaidi, M. U. M., Ahmed, A., Mohammed, M. G., & Siddique, M. S. (2026). Development of High-Performance Catalytic Ceramic Membrane Microchannel Reactor for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Methanol. Membranes, 16(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010045