Antifouling and Antibacterial Activity of Laser-Induced Graphene Ultrafiltration Membrane

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication of LIG on PES UF Substrates

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Membrane Performance

2.5. Permeance and Permeance Recovery Tests

2.6. Cultivation of Bacteria

2.7. Antibacterial Activity of LIG Electrode

2.8. Antibacterial Activity of the Membranes

2.9. Chemical Stability Test

3. Results and Discussion

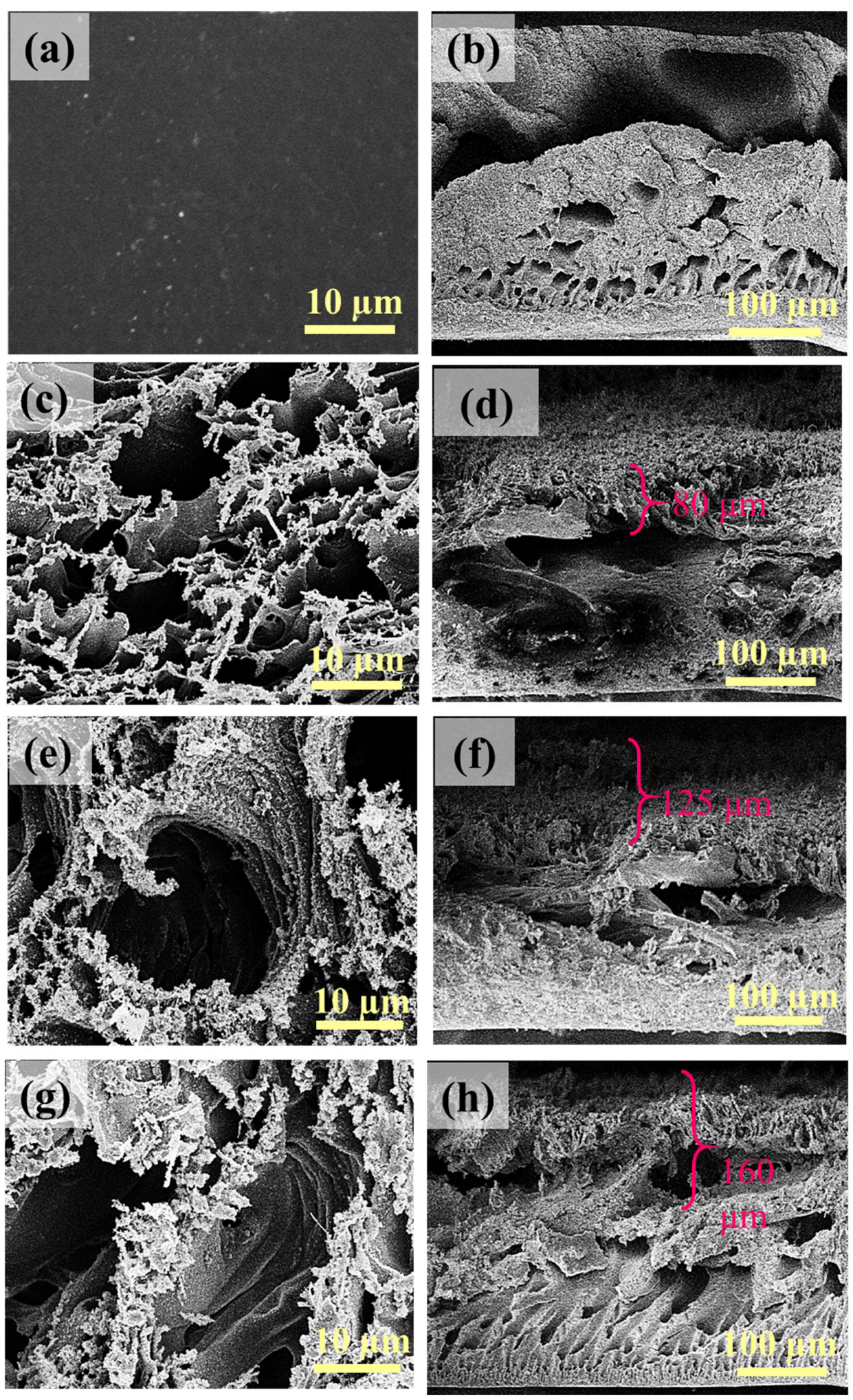

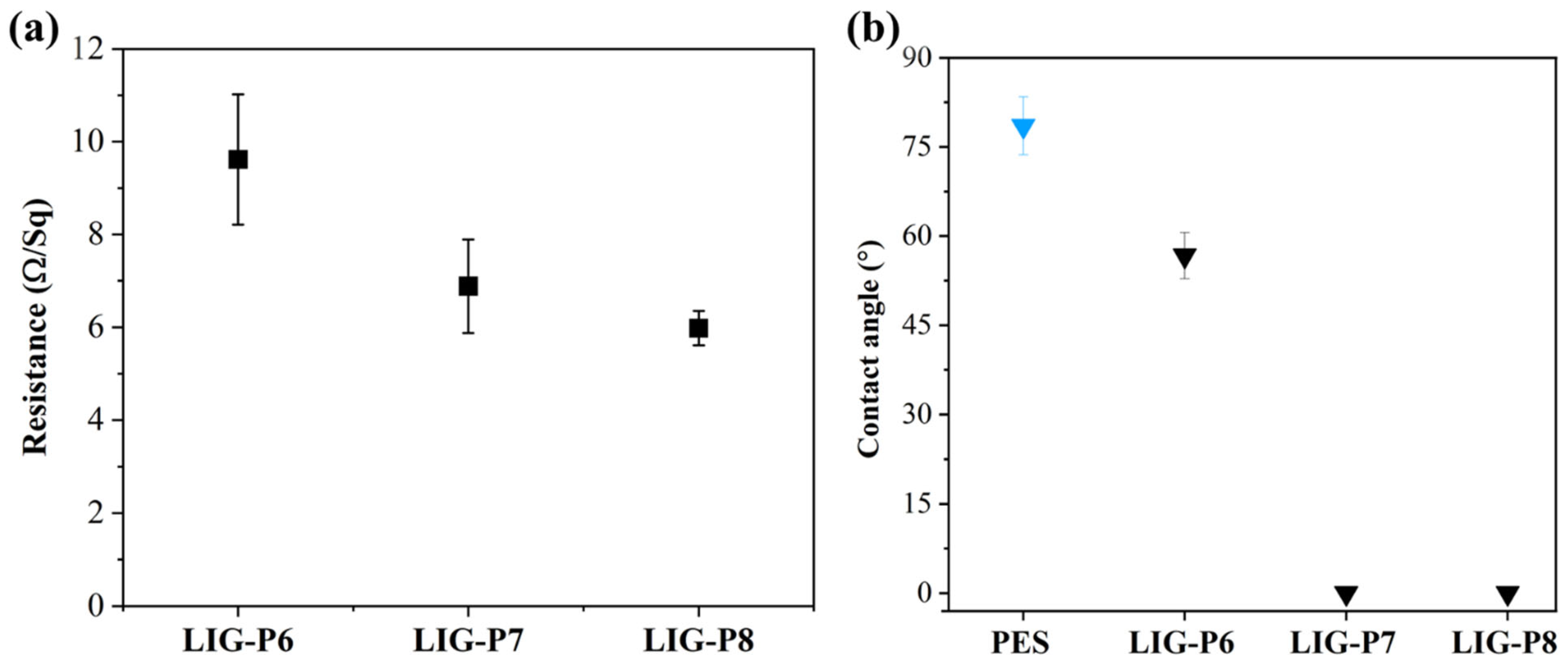

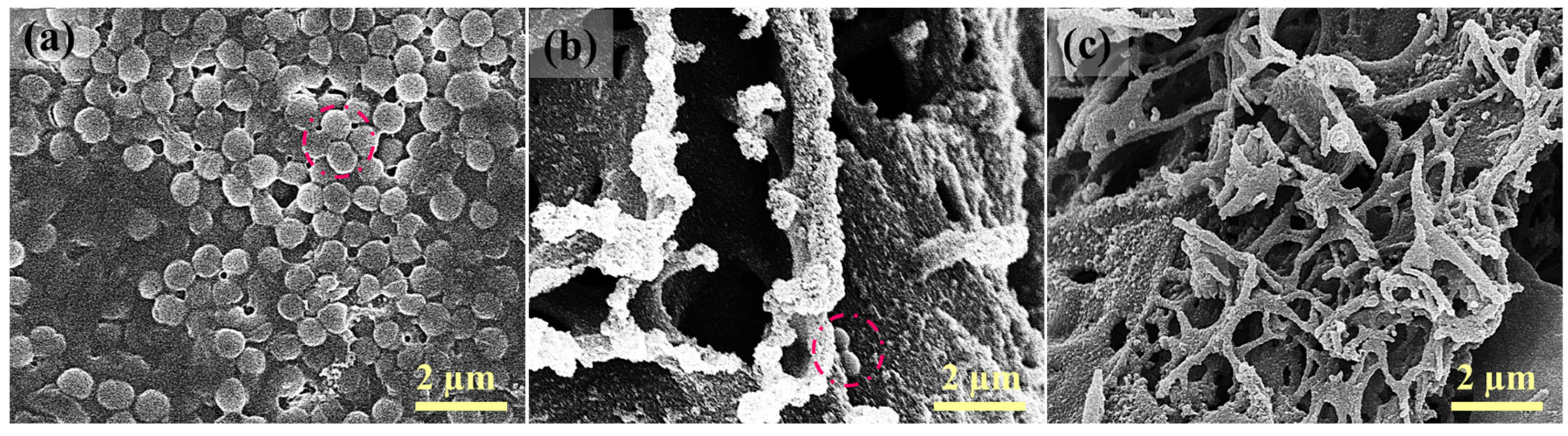

3.1. Characterization of LIG UF Membranes

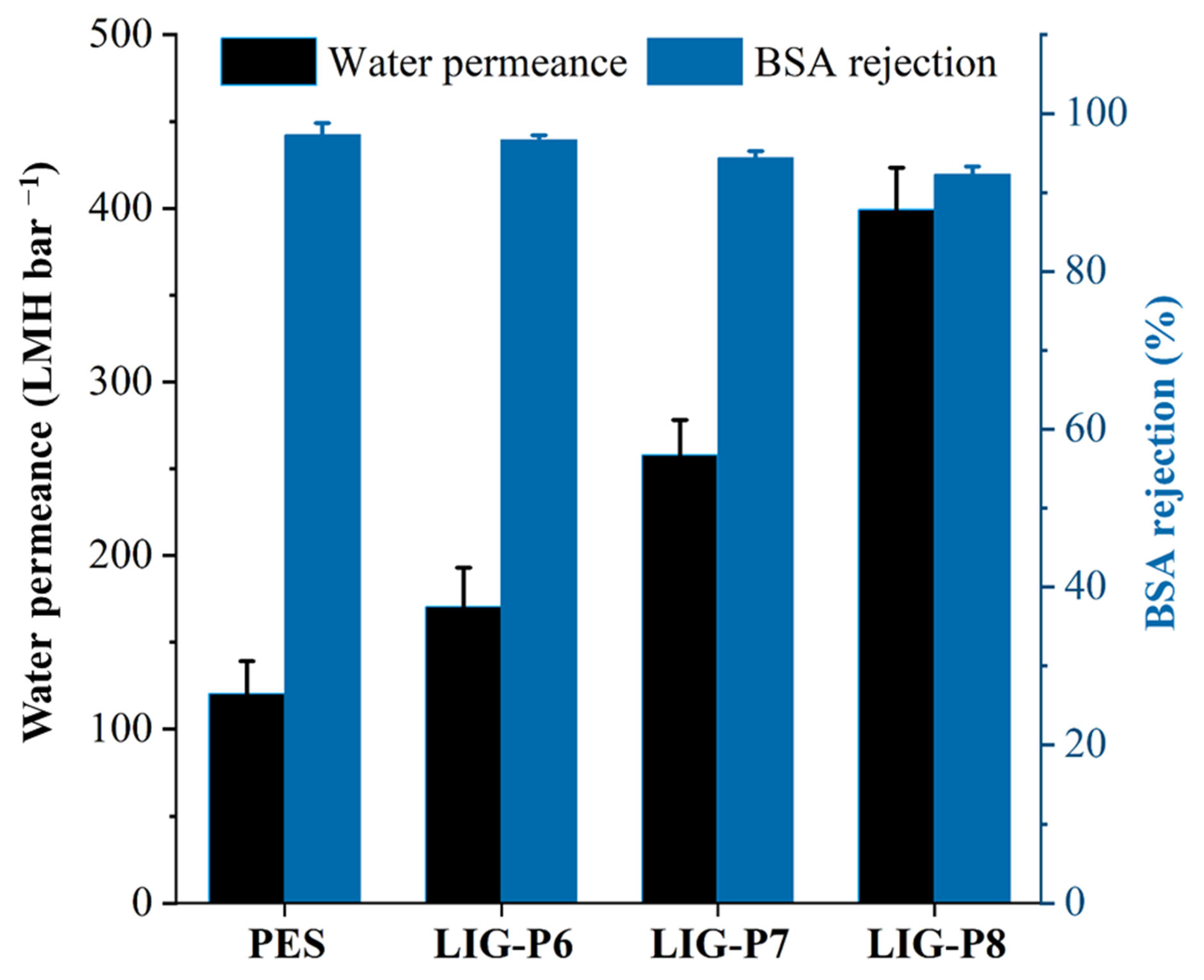

3.2. Performance Evaluation

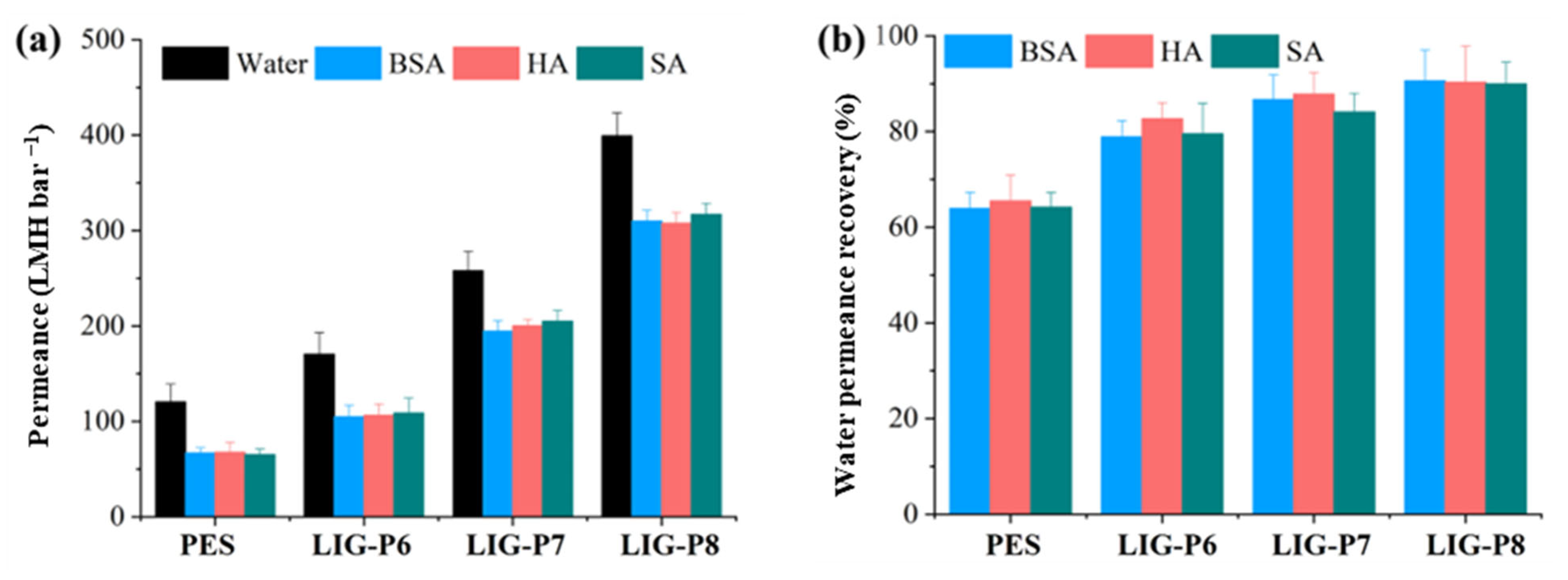

3.3. Anti-Fouling Assessment

3.4. Long-Term Water Permeance and Anti-Fouling Properties

3.5. Antibacterial Activity of LIG Electrode and LIG UF Membrane

4. Conclusions

- It achieved a high water permeance of 400 LMH bar−1 and corresponding BSA rejection of 93%.

- LIG-P8 exhibited lower PDR (22%) and improved permeance recovery (90%) compared to the virgin PES membrane (45% and 64%, respectively).

- The enhanced fouling resistance can be attributed to increased hydrophilicity and surface functionalities on the membrane surface.

- A key feature of the LIG membranes was their highly conductive nature, which effectively killed the S. aureus bacteria upon applying an external potential. The antibacterial rate of the LIG-P8 electrode was enhanced with increasing the applied voltage and contact time. The direct application of voltage assisted with the destruction of cell membranes, leading to bacterial killing, which is attributed to the chemical oxidative species.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Gao, S.; Cui, J.; Huang, C.; Fu, G. Biomimetic Durable Multifunctional Self-Cleaning Nanofibrous Membrane with Outstanding Oil/Water Separation, Photodegradation of Organic Contaminants, and Antibacterial Performances. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 34999–35010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Cui, J.; Qu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Huang, C.; Fu, G. Self-Healing and Superwettable Nanofibrous Membranes with Excellent Stability toward Multifunctional Applications in Water Purification. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 23644–23654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, W.; Ziemann, E.; Be’er, A.; Lu, X.; Elimelech, M.; Bernstein, R. Functionalization of Ultrafiltration Membrane with Polyampholyte Hydrogel and Graphene Oxide to Achieve Dual Antifouling and Antibacterial Properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 565, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, K.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y. Novel Control Strategy for Membrane Biofouling by Surface Loading of Aerobically and Anaerobically Applicable Photocatalytic Optical Fibers Based on a Z-Scheme Heterostructure Zr-MOFs/RGO/Ag3PO4Photocatalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6608–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plisko, T.V.; Bildyukevich, A.V.; Karslyan, Y.A.; Ovcharova, A.A.; Volkov, V.V. Development of High Flux Ultrafiltration Polyphenylsulfone Membranes Applying the Systems with Upper and Lower Critical Solution Temperatures: Effect of Polyethylene Glycol Molecular Weight and Coagulation Bath Temperature. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 565, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Zhao, W.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Bai, J.; Zhang, L. Antifouling Fibrous Membrane Enables High Efficiency and High-Flux Microfiltration for Water Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 49254–49265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Du, X.-A.; Liu, Y.; Ju, Y.; Song, S.; Dong, L. A High-Efficiency Ultrafiltration Nanofibrous Membrane with Remarkable Antifouling and Antibacterial Ability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 15191–15199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Miao, R.; Wang, X.; Lv, Y.; Meng, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, D.; Feng, L.; Liu, Z.; Ju, K. Fouling Behavior of Typical Organic Foulants in Polyvinylidene Fluoride Ultrafiltration Membranes: Characterization from Microforces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 3708–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, T.; Shi, J.; Wang, W.; Teng, K.; Qian, X.; Shan, M.; Deng, H.; Tian, X.; Li, C.; et al. Manipulating Migration Behavior of Magnetic Graphene Oxide via Magnetic Field Induced Casting and Phase Separation toward High-Performance Hybrid Ultrafiltration Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18418–18429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitounis, D.; Ali-Boucetta, H.; Hong, B.H.; Min, D.H.; Kostarelos, K. Prospects and Challenges of Graphene in Biomedical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2258–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill Choi, B.; Park, H.; Jung Park, T.; Ho Yang, M.; Sung Kim, J.; Jang, S.-Y.; Su Heo, N.; Yup Lee, S.; Kong, J.; Hi Hong, W. Solution Chemistry of Self-Assembled Graphene Nanohybrids for High-Performance Flexible Biosensors. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2910–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano, D.C.; Kosynkin, D.V.; Berlin, J.M.; Sinitskii, A.; Sun, Z.; Slesarev, A.; Alemany, L.B.; Lu, W.; Tour, J.M. Improved Synthesis of Graphene Oxide. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4806–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, F.; Fonseca de Faria, A.; Elimelech, M. Environmental Applications of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5861–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.H.; Huang, Y.; Yu, M.; Her, N.; Flora, J.R.V.; Park, C.M.; Kim, S.; Cho, J.; Yoon, Y. Evaluation of Humic Acid and Tannic Acid Fouling in Graphene Oxide-Coated Ultrafiltration Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22270–22279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Quan, X.; Chen, S.; Yu, H. Superpermeable Atomic-Thin Graphene Membranes with High Selectivity. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 1920–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Huang, H.; Xiao, C.; Zheng, S.; Shi, X.; Qin, J.; Fu, Q.; Bao, X.; Feng, X.; Müllen, K.; et al. Electrochemically Scalable Production of Fluorine-Modified Graphene for Flexible and High-Energy Ionogel-Based Microsupercapacitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8198–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, M.F.; Kaner, R.B. Scalable Fabrication of High-Power Graphene Micro-Supercapacitors for Flexible and on-Chip Energy Storage. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tour, J.M. Top-Down versus Bottom-Up Fabrication of Graphene-Based Electronics. Chemistry 2013, 26, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supur, M.; Dyck, C.V.; Bergren, A.J.; Mccreery, R.L. Bottom-up, Robust Graphene Ribbon Electronics in All-Carbon Molecular Junctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 6090–6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.L.; Larosa, J.M.; Luo, X.; Cui, X.T. Electrically Controlled Drug Delivery from Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Films. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1834–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Grüner, G.; Zhao, Y. Recent Advancements of Graphene in Biomedicine. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 2542–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Deng, E.; Park, D.; Pfeifer, B.A.; Dai, N.; Lin, H. Grafting Activated Graphene Oxide Nanosheets onto Ultrafiltration Membranes Using Polydopamine to Enhance Antifouling Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 48179–48187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ruiz-Zepeda, F.; Ye, R.; Samuel, E.L.G.G.; Yacaman, M.J.; Yakobson, B.I.; Tour, J.M. Laser-Induced Porous Graphene Films from Commercial Polymers. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.K.; Mahbub, H.; Nowrin, F.H.; Malmali, M. Highly Robust Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) Ultrafiltration Membrane with a Stable Microporous Structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 46884–46895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.K.; Lin, B.; Nowrin, F.H.; Malmali, M. Comparing Structure and Sorption Characteristics of Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) from Various Polymeric Substrates. ACS Environ. Sci. Technol. Water 2022, 2, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamaraiselvan, C.; Wang, J.; James, D.K.; Narkhede, P.; Singh, S.P.; Jassby, D.; Tour, J.M.; Arnusch, C.J. Laser-Induced Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes as Conductive Carbon-Based Materials in Environmental Technology. Mater. Today 2020, 34, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsman, D.S.; Getachew, B.A.; Cooper, C.B.; Grossman, J.C. Preserving Nanoscale Features in Polymers during Laser Induced Graphene Formation Using Sequential Infiltration Synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinam, K.; Singh, S.P.; Li, Y.; Kasher, R.; Tour, J.M.; Arnusch, C.J. Polyimide Derived Laser-Induced Graphene as Adsorbent for Cationic and Anionic Dyes. Carbon 2017, 124, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Sha, J.; Fei, H.; Li, Y.; Tour, J.M. Efficient Water-Splitting Electrodes Based on Laser-Induced Graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 26840–26847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ren, M.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Yakobson, B.I.; Tour, J.M. Oxidized Laser-Induced Graphene for Efficient Oxygen Electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Ye, R.; Mann, J.A.; Zakhidov, D.; Li, Y.; Smalley, P.R.; Lin, J.; Tour, J.M. Flexible Boron-Doped Laser-Induced Graphene Microsupercapacitors. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 5868–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyk, B.; Silva, B.; Carvalho, A.; Silvestre, S.; Fernandes, A.; Martins, R.; Fortunato, E.; Costa, F. Laser-Induced Graphene from Paper for Mechanical Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 10210–10221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanford, M.G.; Yang, K.; Chyan, Y.; Kittrell, C.; Tour, J.M. Laser-Induced Graphene for Flexible and Embeddable Gas Sensors. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 3474–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.P.; Li, Y.; Be’er, A.; Oren, Y.; Tour, J.M.; Arnusch, C.J. Laser-Induced Graphene Layers and Electrodes Prevents Microbial Fouling and Exerts Antimicrobial Action. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 18238–18247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tour, J.M.; Arnusch, C.J.; Singh, S.P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tour, J.M.; Arnusch, C.J. Sulfur-Doped Laser-Induced Porous Graphene Derived from Polysulfone-Class Polymers and Membranes. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, D.X.; Yang, K.; Yoon, J.; Singh, S.P.; Wang, T.; Arnusch, C.J.; Tour, J.M. Laser-Induced Graphene Composites as Multifunctional Surfaces. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 2579–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, H.; Nowrin, F.H.; Saed, M.A.; Malmali, M. Radiofrequency-Triggered Surface-Heated Laser-Induced Graphene Membranes for Enhanced Membrane Distillation. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2025, 13, 1950–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Belfort, G. Correcting for Surface Roughness: Advancing and Receding Contact Angles Contact Angle. Langmuir 2002, 18, 6465–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Singh, S.P.; Nunes Kleinberg, M.; Gupta, A.; Arnusch, C.J.; Kleinberg, M.N.; Gupta, A.; Arnusch, C.J. Laser-Induced Graphene-PVA Composites as Robust Electrically Conductive Water Treatment Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 10914–10921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamaraiselvan, C.; Thakur, A.K.; Gupta, A.; Arnusch, C.J. Electrochemical Removal of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants Using Robust Laser-Induced Graphene Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 1452–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sharma, C.P.; Arnusch, C.J. Simple Scalable Fabrication of Laser-Induced Graphene Composite Membranes for Water Treatment. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Pandey, R.P.; Shahi, V.K. Preparation, Characterization and Thermal Degradation Studies of Bi-Functional Cation-Exchange Membranes. Desalination 2015, 367, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sreedhar, N.; Jaoude, M.A.; Arafat, H.A. High-Flux, Antifouling Hydrophilized Ultrafiltration Membranes with Tunable Charge Density Combining Sulfonated Poly(Ether Sulfone) and Aminated Graphene Oxide Nanohybrid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 12, 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.-N.; He, M.; Jiang, Z.; Su, Y. Improving Permeation and Antifouling Performance of Polyamide Nanofiltration Membranes through the Incorporation of Arginine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13577–13586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, R.W.; WU, D.; Howell, J.A.; Gupta, B.B. Critical flux concept for microfiltration fouling. J. Membr. Sci. 1995, 100, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hasan, H.; Muhammad, M.H.; Ismail, N.’I. A Review of Biological Drinking Water Treatment Technologies for Contaminants Removal from Polluted Water Resources. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 33, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, R.; Al-Khtheeri, H.; Weerasekera, D.; Fernando, N.; Vaira, D.; Holton, J.; Basset, C. Bactericidal and Anti-Adhesive Properties of Culinary and Medicinal Plants against Helicobacter Pylori. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 7499–7507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaeni, S.S. The Application of Membrane Technology for Water Disinfection. Water Res. 1999, 33, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Zeev, E.; Passow, U.; Romero-Vargas Castrillón, S.; Elimelech, M. Transparent Exopolymer Particles: From Aquatic Environments and Engineered Systems to Membrane Biofouling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horseman, T.; Yin, Y.; Christie, K.S.; Wang, Z.; Tong, T.; Lin, S. Wetting, Scaling, and Fouling in Membrane Distillation: State-of-the-Art Insights on Fundamental Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies. ACS EST Eng. 2020, 1, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, I.-M.; Malmali, M. Scaling Behavior in Membrane Distillation: Effect of Biopolymers and Antiscalants. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, I.-M.; Lin, B.; Matinpour, H.; Malmali, M. In-Situ Imaging to Elucidate on Scaling and Wetting in Membrane Distillation. Desalination 2024, 577, 117393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcelli, N.; Judd, S. Chemical Cleaning of Potable Water Membranes: A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 71, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, H.; Rocha, L.; Lopez, A.; Matinpour, H.; Malmali, M. Reverse Osmosis for Desalination of Partially Desalinated Produced Water to Meet the Regulatory Standards. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 736, 124669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Li, X.; Wan, C.; Chung, T.-S. Zwitterionic Polymers Grafted Poly(Ether Sulfone) Hollow Fiber Membranes and Their Antifouling Behaviors for Osmotic Power Generation. J. Memb. Sci. 2016, 497, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Zhang, D.R.; He, Y.; Zhao, X.S.; Bai, R. Modification of Membrane Surface for Anti-Biofouling Performance: Effect of Anti-Adhesion and Anti-Bacteria Approaches. J. Memb. Sci. 2010, 346, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lin, W.; Sun, H.; Wu, L.; Chen, S. A Facile Method for Polyamide Membrane Modification by Poly(Sulfobetaine Methacrylate) to Improve Fouling Resistance. J. Memb. Sci. 2013, 446, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankovich, T.A.; Gray, D.G. Bactericidal Paper Impregnated with Silver Nanoparticles for Point-of-Use Water Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, S.; Yang, J.; Ma, A. Advancing Strategies of Biofouling Control in Water-Treated Polymeric Membranes. Polymers 2022, 14, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Improved Flux and Anti-Biofouling Performances of Reverse Osmosis Membrane via Surface Layer-by-Layer Assembly. J. Memb. Sci. 2017, 539, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Lagemaat, M.; Grotenhuis, A.; van de Belt-Gritter, B.; Roest, S.; Loontjens, T.J.A.; Busscher, H.J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Ren, Y. Comparison of Methods to Evaluate Bacterial Contact-Killing Materials. Acta Biomater. 2017, 59, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thakur, A.K.; Mahbub, H.; Qavi, I.; Nateqi, M.; Tan, G.; Malmali, M. Antifouling and Antibacterial Activity of Laser-Induced Graphene Ultrafiltration Membrane. Membranes 2026, 16, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010021

Thakur AK, Mahbub H, Qavi I, Nateqi M, Tan G, Malmali M. Antifouling and Antibacterial Activity of Laser-Induced Graphene Ultrafiltration Membrane. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleThakur, Amit K., Hasib Mahbub, Imtiaz Qavi, Masoud Nateqi, George Tan, and Mahdi Malmali. 2026. "Antifouling and Antibacterial Activity of Laser-Induced Graphene Ultrafiltration Membrane" Membranes 16, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010021

APA StyleThakur, A. K., Mahbub, H., Qavi, I., Nateqi, M., Tan, G., & Malmali, M. (2026). Antifouling and Antibacterial Activity of Laser-Induced Graphene Ultrafiltration Membrane. Membranes, 16(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010021