Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of a Venturi-Integrated Diffuser Design for Membrane Bioreactors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

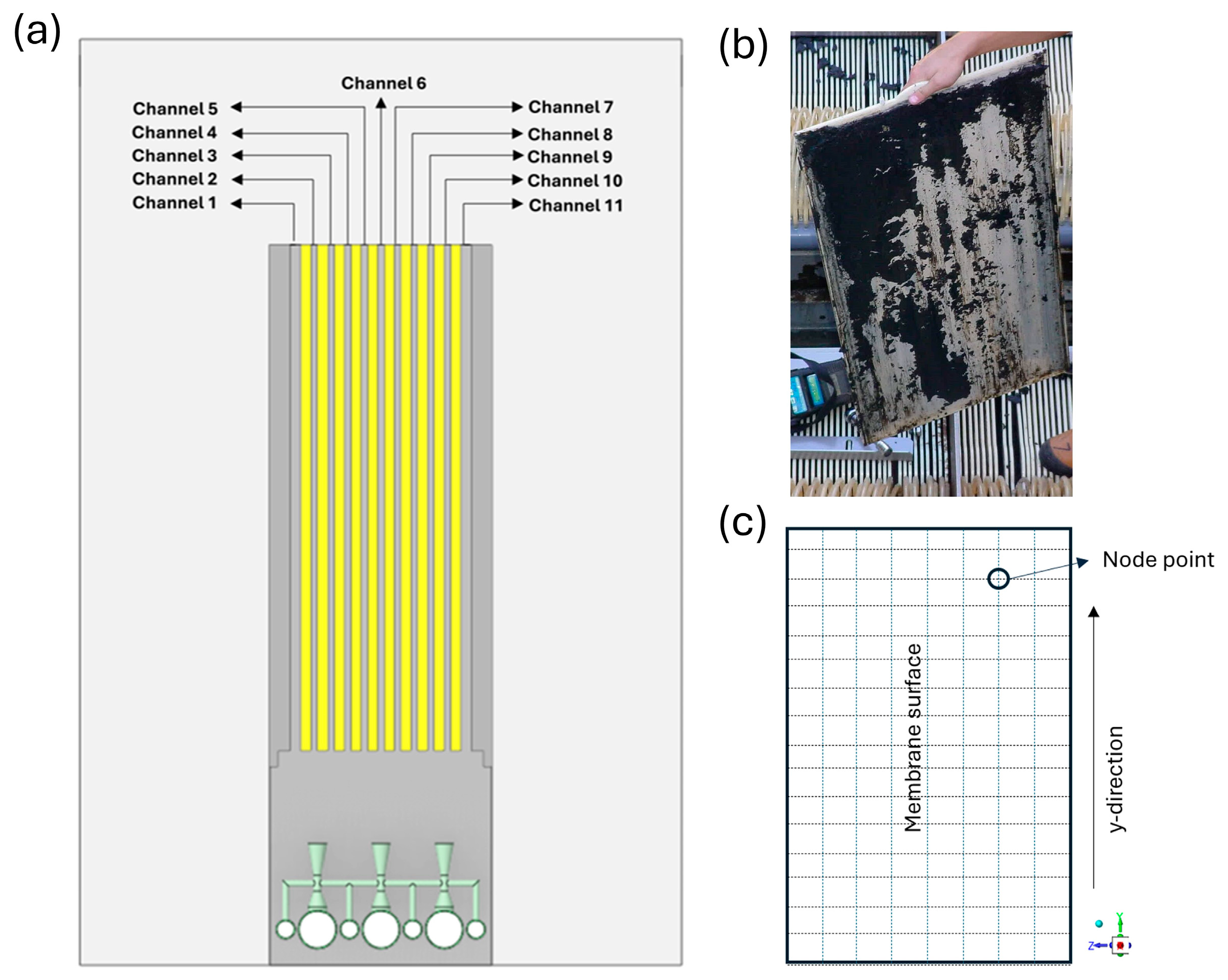

2.1. Model Geometry

2.2. Operating Principle of the Venturi Injector

2.3. Meshing

2.4. Model Setup

3. Results and Discussion

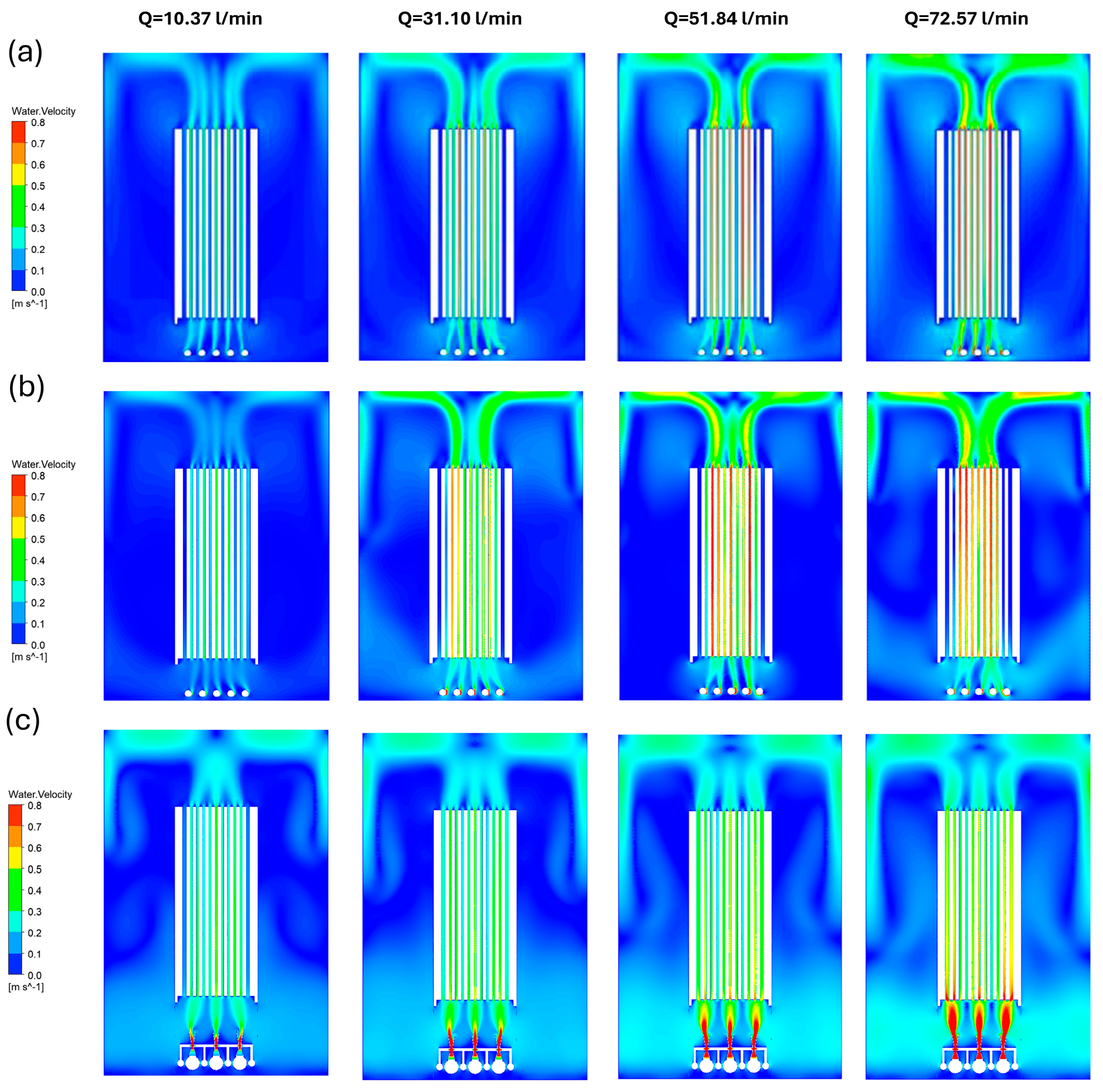

3.1. Comparison of Hydrodynamic Behaviors in Models

3.2. Comparison of Shear Stress Distributions on the Membrane Surface

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, Y. Numerical Investigation of the Aeration Process in the MBR System Equipped with a Flat Sheet Membrane Module. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- López-Serrano, M.J.; Lakho, F.H.; Van Hulle, S.W.H.; Batlles-delaFuente, A. Life cycle cost assessment and economic analysis of a decentralized wastewater treatment to achieve water sustainability within the framework of circular economy. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, K. Comparative Study of Membrane Fouling with Aeration Shear Stress in Filtration of Different Substances. Membranes 2023, 13, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaalp, N. Anoxic Treatment of Agricultural Drainage Water in a Venturi-Integrated Membrane Bioreactor. Membranes 2023, 13, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogarathinam, L.T.; Ismail, A.F.; Goh, P.S. Membrane Bioreactor for Sewage Treatment. In Clean Water: Next Generation Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Drews, A. Membrane fouling in membrane bioreactors—Characterisation, contradictions, cause and cures. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 363, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-D.; Chang, I.-S.; Lee, K.-J. Principles of Membrane Bioreactors for Wastewater Treatment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.; Xie, J.; Pan, Y.; Zou, X.; Sun, F.; Yu, Y.; Xu, R.; Jiang, W.; Chen, C. The optimization and regulation of energy consumption for MBR process: A critical review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, E.; Mehrnia, M.R.; Mousavi, S.M.; Mostoufi, N. Experimental study and computational fluid dynamics simulation of a full-scale membrane bioreactor for municipal wastewater treatment application. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 9930–9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barillon, B.; Ruel, S.M.; Langlais, C.; Lazarova, V. Energy efficiency in membrane bioreactors. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 67, 2685–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, L.; Drews, A.; Prieske, H.; Bérubé, P.R.; Kraume, M. The importance of fluid dynamics for MBR fouling mitigation. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 122, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratkovich, N.; Bentzen, T.R.; Bérubé, P.; Heinen, N.; Rasmussen, M.R. Energy consumption related to shear stress for membrane bioreactors used for wastewater treatment. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems, ECOS, Novi Sad, Serbia, 4–7 July 2011; pp. 2195–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Kayaalp, N.; Ozturkmen, G. A venturi device reduces membrane fouling in a submerged membrane bioreactor. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, E.; Kayaalp, N. Modelling of hydrogenotrophic denitrification process in a venturi-integrated membrane bioreactor. Environ. Technol. 2024, 45, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaalp, N.; Ozturkmen, G.; Gul, E.; Gunay, E. A comparison of a blower and a Venturi aeration system in a submerged membrane bioreactor. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017, 69, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englehardt, J.D.; Wu, T.; Tchobanoglous, G. Urban net-zero water treatment and mineralization: Experiments, modeling and design. Water Res. 2013, 47, 4680–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, H.; Huang, Y.; He, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, K. Design and structural parameter optimization of Venturi-type microbubble reactor for wastewater treatment by CFD simulation. J. Flow Chem. 2024, 14, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, L.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Q.; Yu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Duan, J. Novel Venturi injector reactor design and application in ammonia nitrogen wastewater treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Wu, Q.; Ye, Q.; Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Yue, R.; Teng, J.; Hong, H.; Liao, B.-Q. Superior performance of a membrane bioreactor through innovative in-situ aeration and structural optimization using computational fluid dynamics. Water Res. 2023, 243, 120353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, N.; Farahsary, P.S.; Targhi, M.M. CFD Modeling of Fouling by Biological Materials in Tubular Membrane in Submerged Membrane Bioreactor with ANSYS FLUENT Software. Appl. Res. J. 2016, 2, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, R.; Deveci, G.; Turken, T.; Sengur, R.; Guclu, S.; Koseoglu-Imer, D.Y.; Koyuncu, I. Analysis of wall shear stress on the outside-in type hollow fiber membrane modules by CFD simulation. Desalination 2014, 351, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, L.; Chang, J.; Dong, S.; Xiao, F. Optimizing slug bubble size for application of the ultra-thin flat sheet membranes in MBR: A comprehensive study combining CFD simulation and experiment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 15322–15338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengel, Y.; Cimbala, J. Ebook: Fluid Mechanics Fundamentals and Applications (Si Units); McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Yan, X.; Xiao, K.; Guan, J.; Li, T.; Liang, P.; Huang, X. Optimization of membrane unit location in a full-scale membrane bioreactor using computational fluid dynamics. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 249, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Waite, T.D.; Leslie, G. Numerical simulation of bubble induced shear in membrane bioreactors: Effects of mixed liquor rheology and membrane configuration. Water Res. 2015, 75, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansys Fluent Theory Guide. Available online: https://www.ansys.com/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Khalili-Garakani, A.; Mehrnia, M.R.; Mostoufi, N.; Sarrafzadeh, M.H. Analyze and control fouling in an airlift membrane bioreactor: CFD simulation and experimental studies. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Brannock, M.; Leslie, G. Membrane bioreactors: Overview of the effects of module geometry on mixing energy. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2009, 4, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weia, K.C.; Jinsonga, H.; Jinga, L.; Liub, W.; Jordanb, E.; Kuzmab, M. Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to Optimize the Hydrodynamic in Large Scale Membrane Tanks. In Proceedings of the Water Environment Federation Technical Exhibition and Conference WEFTEC, Chicago, IL, USA, 18–22 October 2008; pp. 3012–3026. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Vedantam, S.; Spanjers, H.; Nopens, I.; van Lier, J.B. Analysis of mass transfer characteristics in a tubular membrane using CFD modeling. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4705–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, Q.; Dai, P.; Guan, J.; Waite, T.D.; Leslie, G. CFD modelling of uneven flows behaviour in flat-sheet membrane bioreactors: From bubble generation to shear stress distribution. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 570, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, S. The MBR Book: Principles and Applications of Membrane Bioreactors for Water and Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, F.J., Jr. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for goodness of fit. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1951, 46, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Min. Mesh Size [mm] | Max. Mesh Size [mm] | Mesh Type | Mesh Number | Skewness | Aspect Ratio | Average Velocity [m/s] | Average Shear Stress [Pa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5 | 13 | Polyhedral | 114,162 | 0.69 | 11.59 | 0.1364 | 0.6052 |

| 2 | 0.4 | 9 | Polyhedral | 340,407 | 0.58 | 8.21 | 0.1406 | 0.6312 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 7 | Polyhedral | 575,909 | 0.50 | 6.27 | 0.1433 | 0.6673 |

| 4 | 0.3 | 5 | Polyhedral | 894,025 | 0.50 | 6.22 | 0.1467 | 0.6787 |

| 5 | 0.2 | 5 | Polyhedral | 985,088 | 0.52 | 6.83 | 0.1552 | 0.6883 |

| 6 | 0.2 | 4 | Polyhedral | 1,450,079 | 0.48 | 6.09 | 0.1584 | 0.6911 |

| 7 | 0.2 | 3.5 | Polyhedral | 1,970,998 | 0.45 | 5.70 | 0.1597 | 0.6920 |

| Simulation Methods and Conditions | Standard Scenario | |

|---|---|---|

| Models | Phase | Two-phase: liquid–gas |

| Multiphase model | Eulerian model | |

| Turbulent model | Standard k–ε | |

| Near-wall function | Standard wall functions | |

| Boundary conditions | Inlet-1 (water inlet) | Velocity-inlet (Only V-MBR) |

| Inlet-2 (air inlet) | Pressure-inlet | |

| Outlet-1 (MBR surface) | Degassing | |

| Outlet-2 (water outlet) | Pressure-outlet (Only V-MBR) | |

| Membrane surface | Wall | |

| Solution methods | Pressure–velocity coupling | Phase-coupled SIMPLE |

| Spatial Discretization for gradient | Least squares cell-based | |

| Spatial Discretization for momentum | Quick | |

| Spatial Discretization for volume fraction | Quick | |

| Solution controls | Pressure | 0.5 |

| Intensity | 1 | |

| Momentum | 0.2 | |

| Turbulent Kinetic Energy | 0.8 |

| Shear Stress (Pa) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel No | Model | Number of Values | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | Std. Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| 1 | S-MBR | 20,809 | 0.00013 | 0.41480 | 0.02553 | 0.03238 | 0.03112 | 96.09% | 3.85000 | 24.54000 |

| V-MBR | 21,255 | 0.01123 | 1.26000 | 0.41580 | 0.42070 | 0.22700 | 53.95% | 0.01658 | −1.16200 | |

| 2 | S-MBR | 20,856 | 0.00064 | 1.07600 | 0.35130 | 0.37420 | 0.16810 | 44.91% | 0.27760 | −0.10200 |

| V-MBR | 21,148 | 0.53090 | 2.23500 | 1.24800 | 1.24000 | 0.20480 | 16.52% | 0.01591 | −0.69750 | |

| 3 | S-MBR | 20,893 | 0.00326 | 2.77300 | 1.25100 | 1.17200 | 0.35140 | 29.99% | −1.25500 | 2.84900 |

| V-MBR | 21,109 | 0.45510 | 2.04100 | 1.42800 | 1.39800 | 0.24240 | 17.34% | −0.17010 | −1.14900 | |

| 4 | S-MBR | 20,991 | 0.00101 | 2.27500 | 1.10800 | 1.02500 | 0.47450 | 46.30% | −0.61560 | −0.47240 |

| V-MBR | 20,934 | 0.25310 | 1.40300 | 0.88940 | 0.86140 | 0.19240 | 22.34% | −0.32430 | −0.88420 | |

| 5 | S-MBR | 21,184 | 0.00446 | 1.50200 | 0.60630 | 0.60790 | 0.20370 | 33.51% | −0.18780 | 1.43000 |

| V-MBR | 21,172 | 0.52630 | 1.84100 | 1.09100 | 1.09600 | 0.14140 | 12.90% | 0.05714 | −0.74080 | |

| 6 | S-MBR | 21,216 | 0.00720 | 2.65000 | 1.19100 | 1.17800 | 0.27000 | 22.92% | −0.37200 | 3.22600 |

| V-MBR | 20,926 | 0.69720 | 2.22200 | 1.44400 | 1.42100 | 0.17840 | 12.55% | −0.16770 | 0.62580 | |

| 7 | S-MBR | 21,184 | 0.00446 | 1.50200 | 0.60630 | 0.60790 | 0.20370 | 33.51% | −0.18780 | 1.43000 |

| V-MBR | 21,172 | 0.52630 | 1.84100 | 1.09100 | 1.09600 | 0.14140 | 12.90% | 0.05714 | −0.74080 | |

| 8 | S-MBR | 20,991 | 0.00101 | 2.27500 | 1.10800 | 1.02500 | 0.47450 | 46.30% | −0.61560 | −0.47240 |

| V-MBR | 20,934 | 0.25310 | 1.40300 | 0.88940 | 0.86140 | 0.19240 | 22.34% | −0.32430 | −0.88420 | |

| 9 | S-MBR | 20,893 | 0.00326 | 2.77300 | 1.25100 | 1.17200 | 0.35140 | 29.99% | −1.25500 | 2.84900 |

| V-MBR | 21,109 | 0.45510 | 2.04100 | 1.42800 | 1.39800 | 0.24240 | 17.34% | −0.17010 | −1.14900 | |

| 10 | S-MBR | 20,856 | 0.00064 | 1.07600 | 0.35130 | 0.37420 | 0.16810 | 44.91% | 0.27760 | −0.10200 |

| V-MBR | 21,148 | 0.53090 | 2.23500 | 1.24800 | 1.24000 | 0.20480 | 16.52% | 0.01591 | −0.69750 | |

| 11 | S-MBR | 20,809 | 0.00013 | 0.41480 | 0.02553 | 0.03238 | 0.03112 | 96.09% | 3.85000 | 24.54000 |

| V-MBR | 21,255 | 0.01123 | 1.26000 | 0.41580 | 0.42070 | 0.22700 | 53.95% | 0.01658 | −1.16200 | |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test | Mann–Whitney Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel No | p Value | D | p Value | Difference Between Medians | |

| Actual | Hodges–Lehmann | ||||

| 1 | <0.0001 | 0.8787 | <0.0001 | 0.3903 | 0.3832 |

| 2 | <0.0001 | 0.9906 | <0.0001 | 0.8971 | 0.8690 |

| 3 | <0.0001 | 0.3754 | <0.0001 | 0.1772 | 0.2005 |

| 4 | <0.0001 | 0.4190 | <0.0001 | 0.2183 | 0.2302 |

| 5 | <0.0001 | 0.8804 | <0.0001 | 0.4848 | 0.4805 |

| 6 | <0.0001 | 0.4576 | <0.0001 | 0.2533 | 0.2358 |

| 7 | <0.0001 | 0.8804 | <0.0001 | 0.4848 | 0.4805 |

| 8 | <0.0001 | 0.4190 | <0.0001 | 0.2183 | 0.2302 |

| 9 | <0.0001 | 0.3754 | <0.0001 | 0.1772 | 0.2005 |

| 10 | <0.0001 | 0.9906 | <0.0001 | 0.8971 | 0.8690 |

| 11 | <0.0001 | 0.8787 | <0.0001 | 0.3903 | 0.3832 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Batmaz, V.; Kayaalp, N. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of a Venturi-Integrated Diffuser Design for Membrane Bioreactors. Membranes 2026, 16, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010010

Batmaz V, Kayaalp N. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of a Venturi-Integrated Diffuser Design for Membrane Bioreactors. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatmaz, Veli, and Necati Kayaalp. 2026. "Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of a Venturi-Integrated Diffuser Design for Membrane Bioreactors" Membranes 16, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010010

APA StyleBatmaz, V., & Kayaalp, N. (2026). Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of a Venturi-Integrated Diffuser Design for Membrane Bioreactors. Membranes, 16(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010010