Effects of Metal Foam Insertion on the Performance of a Vacuum Membrane Distillation Unit

Abstract

1. Introduction

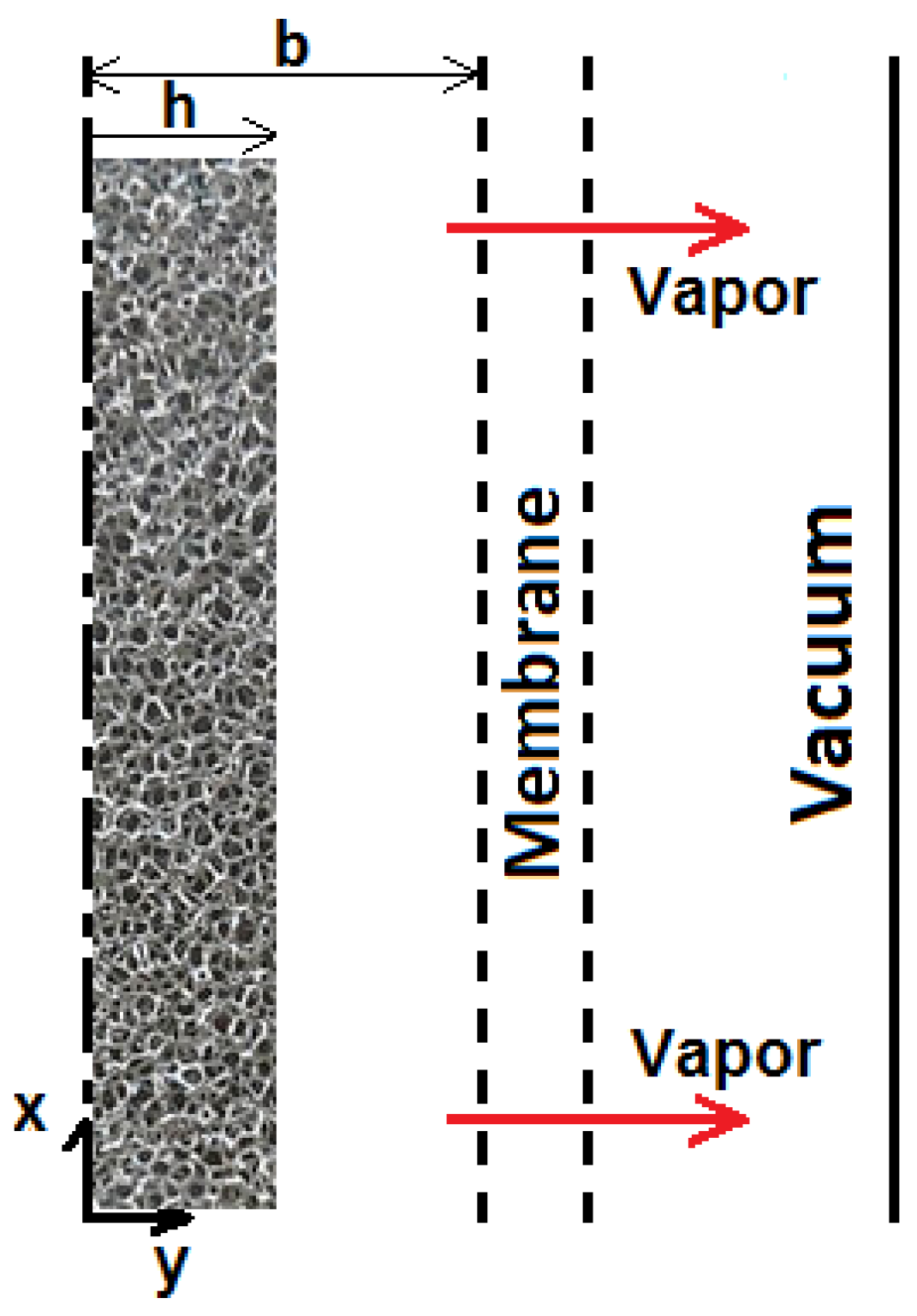

2. Mathematical Model

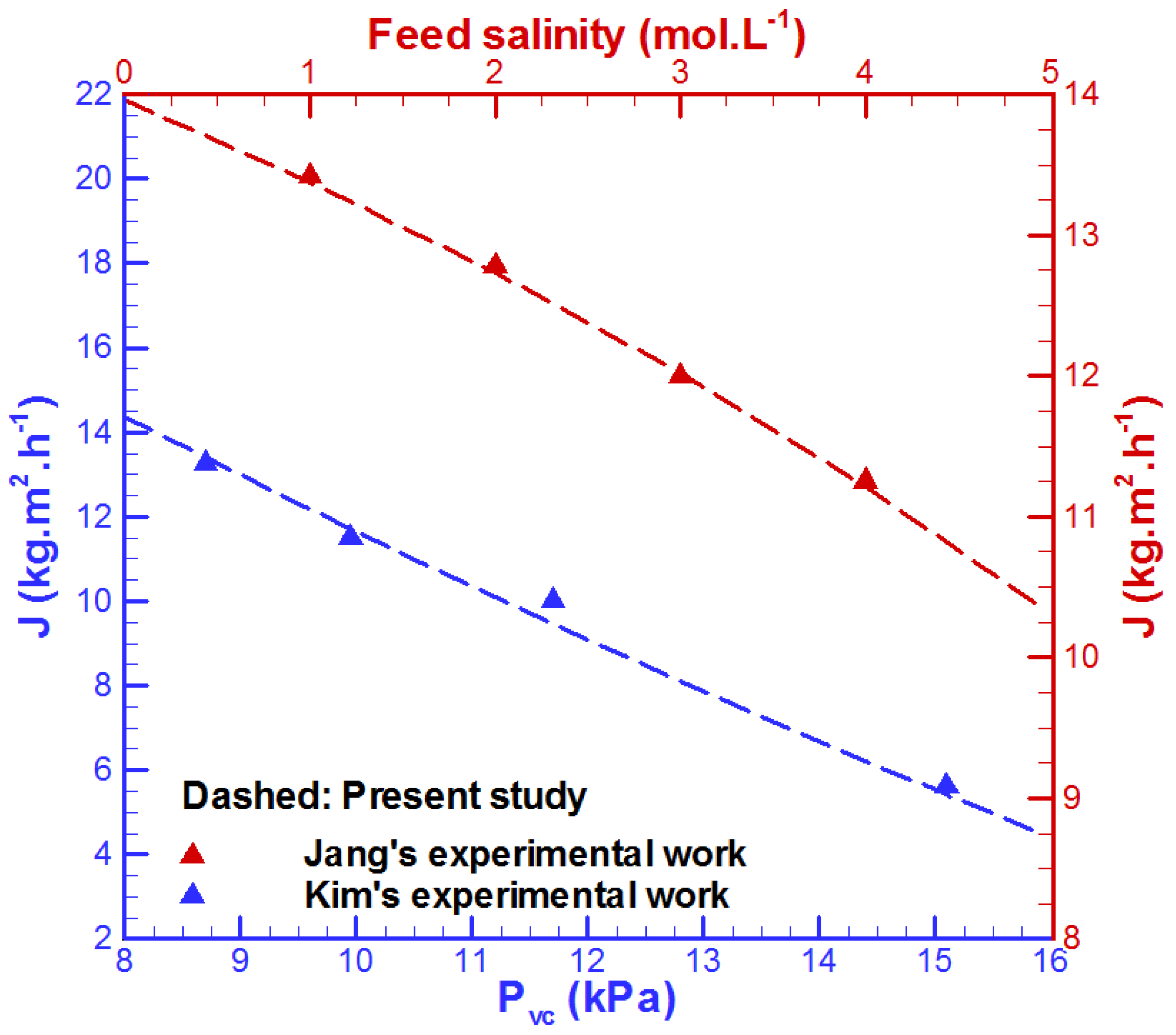

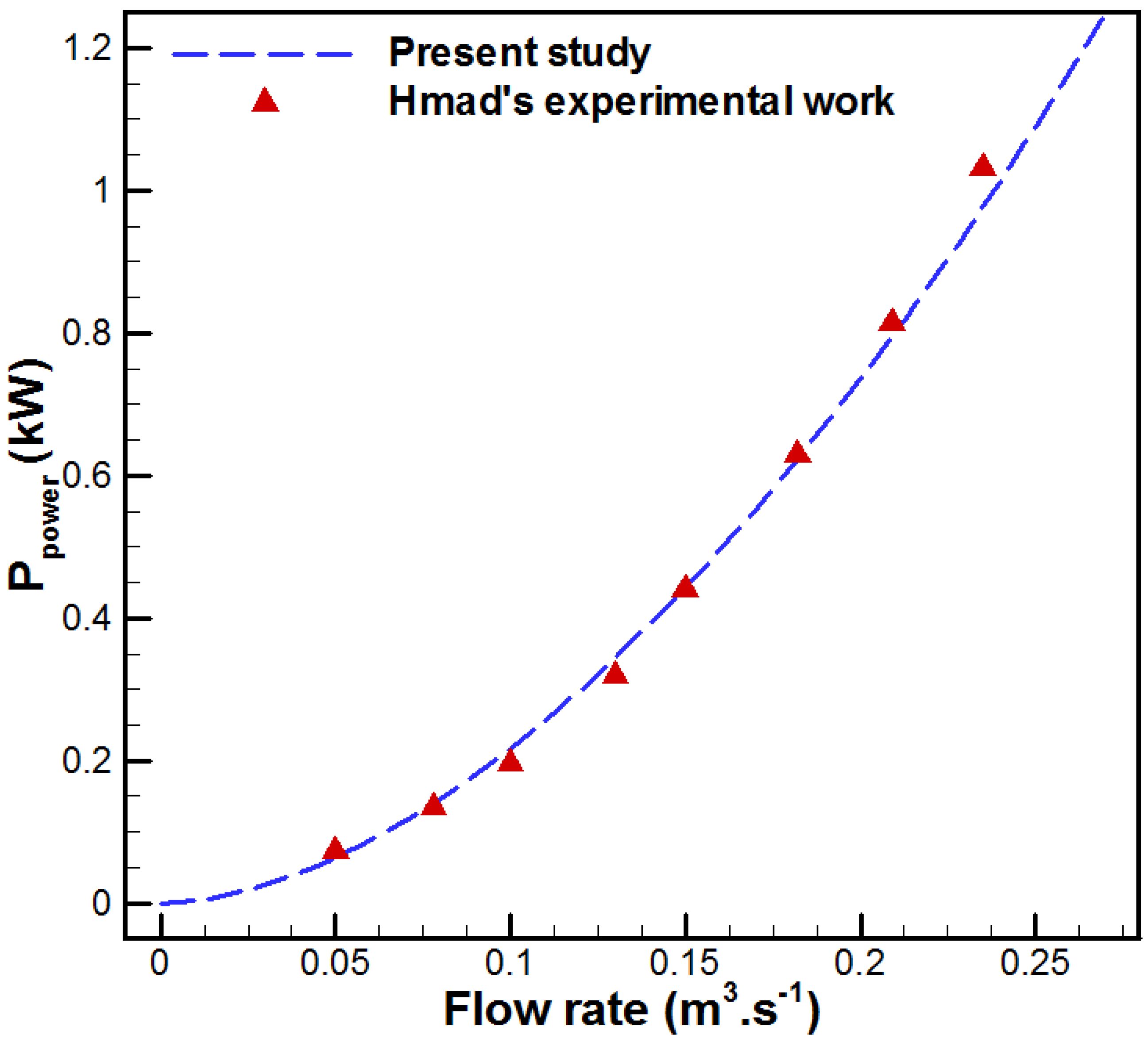

3. Numerical Method and Validation

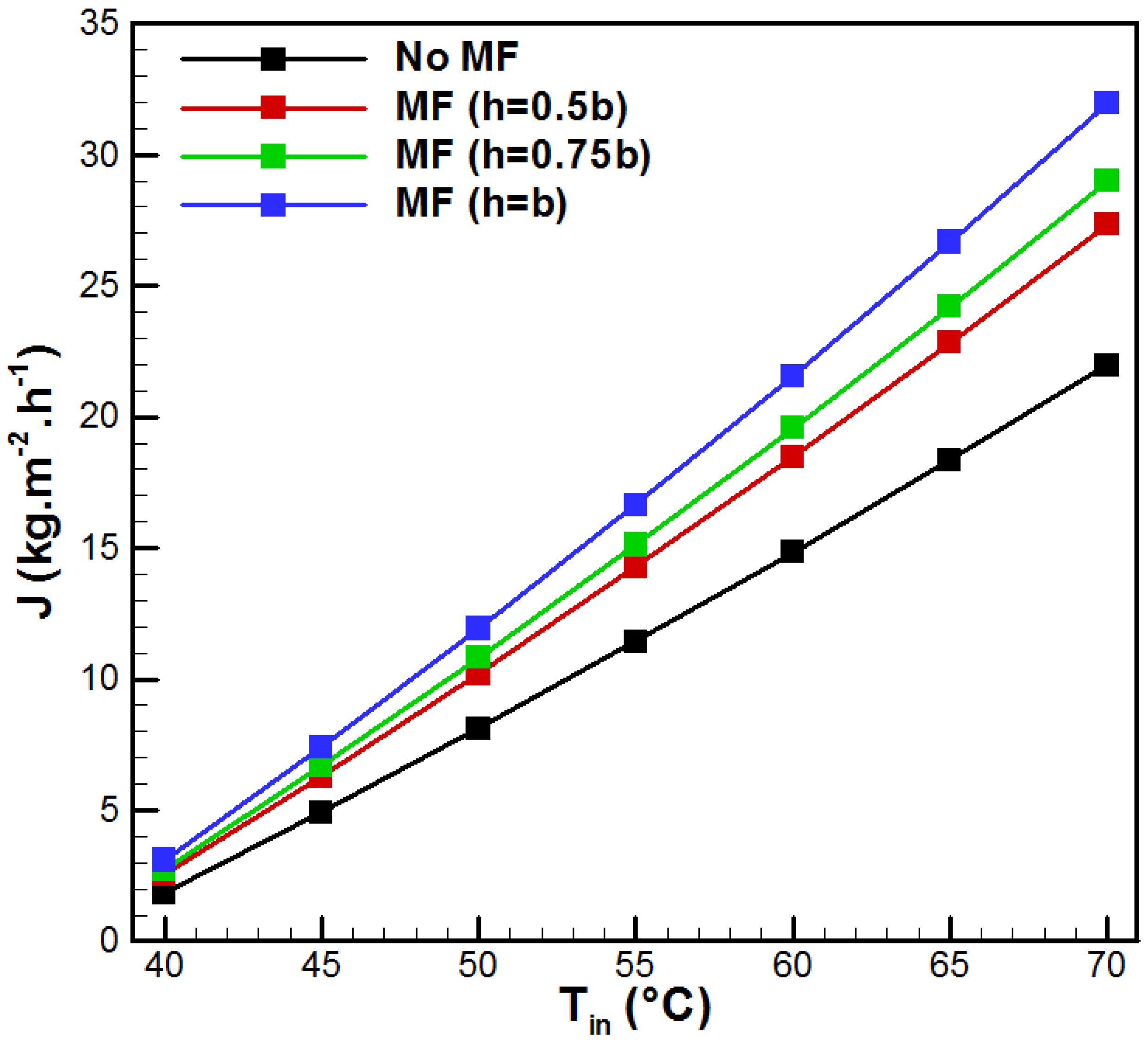

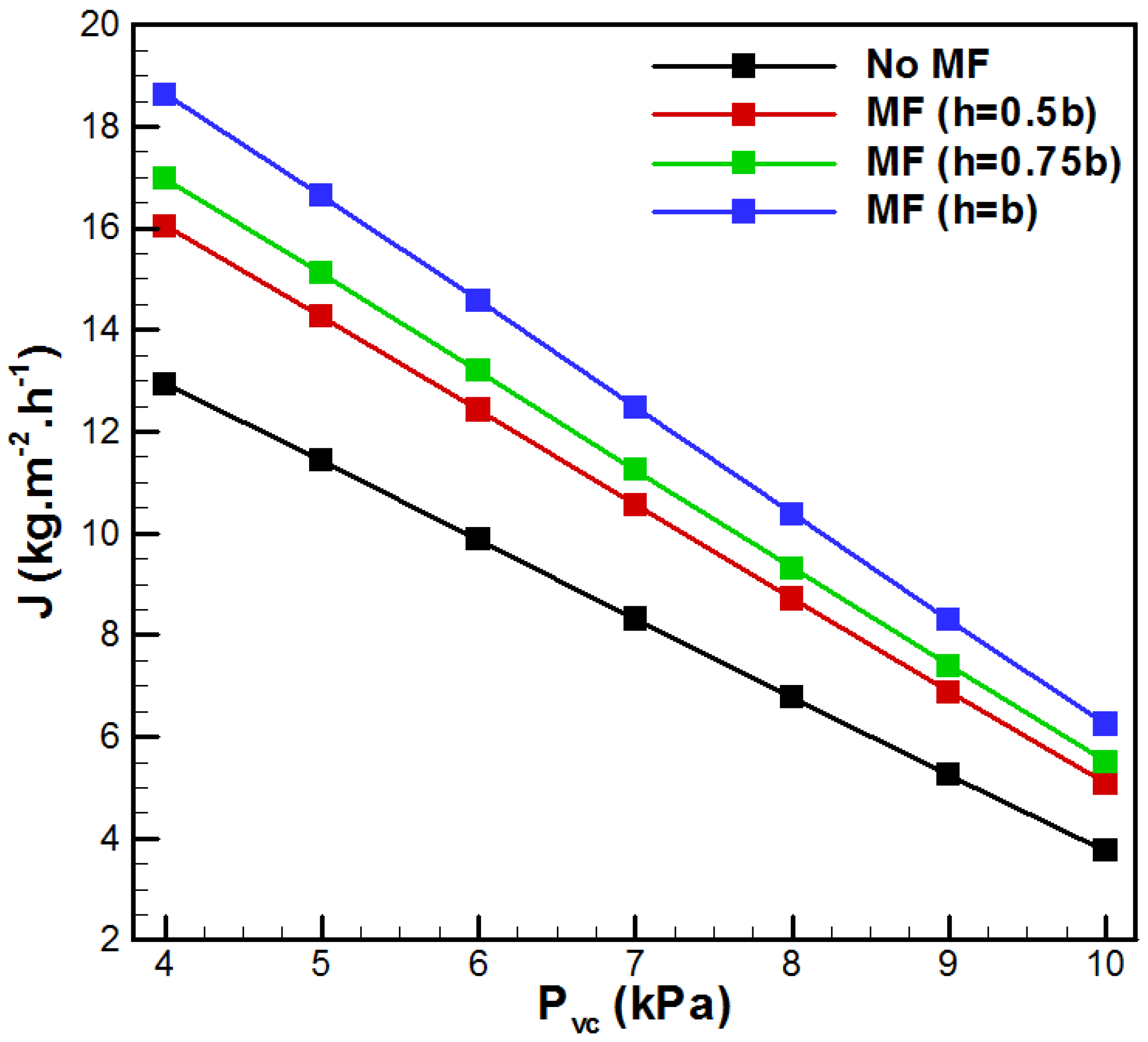

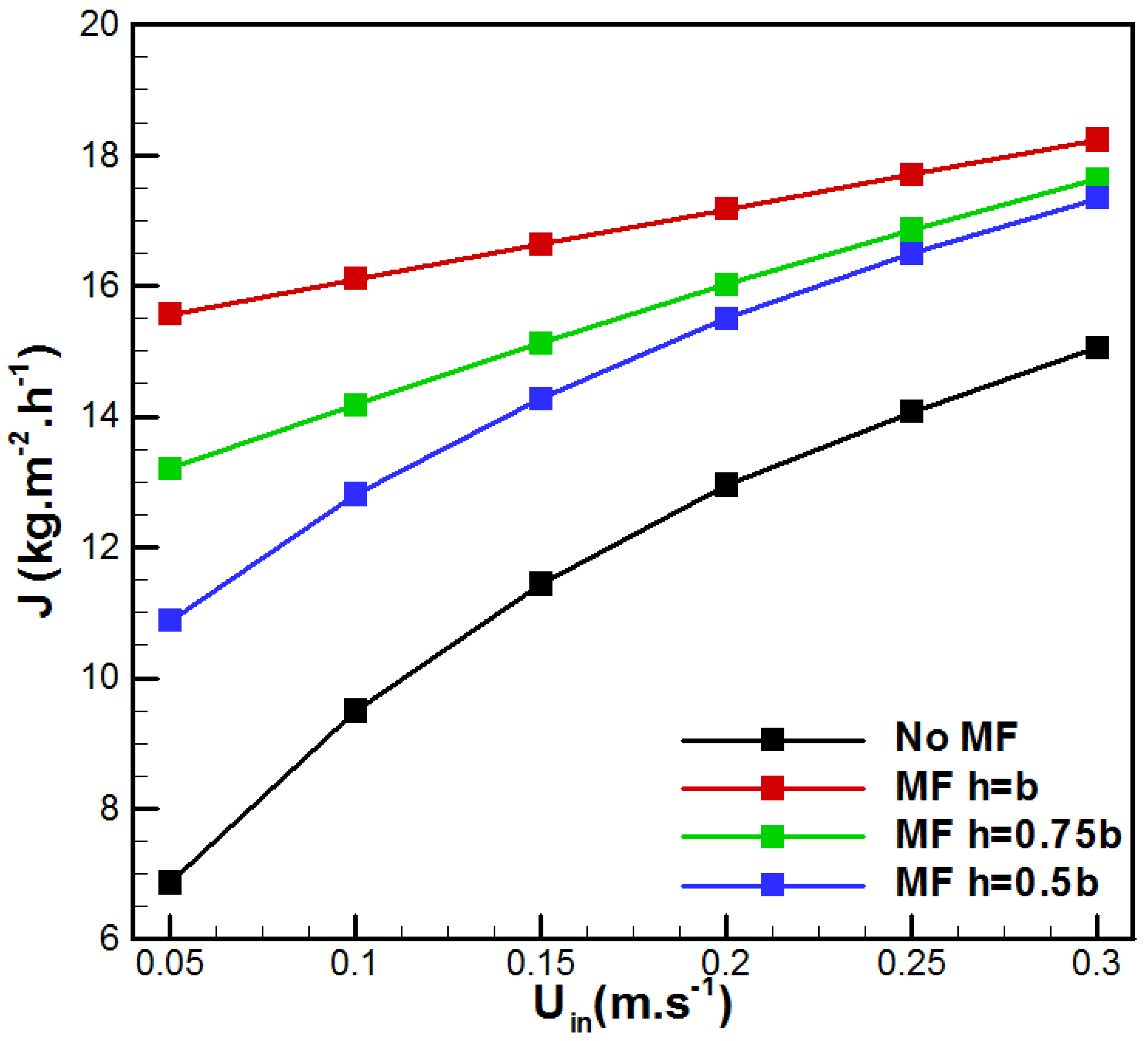

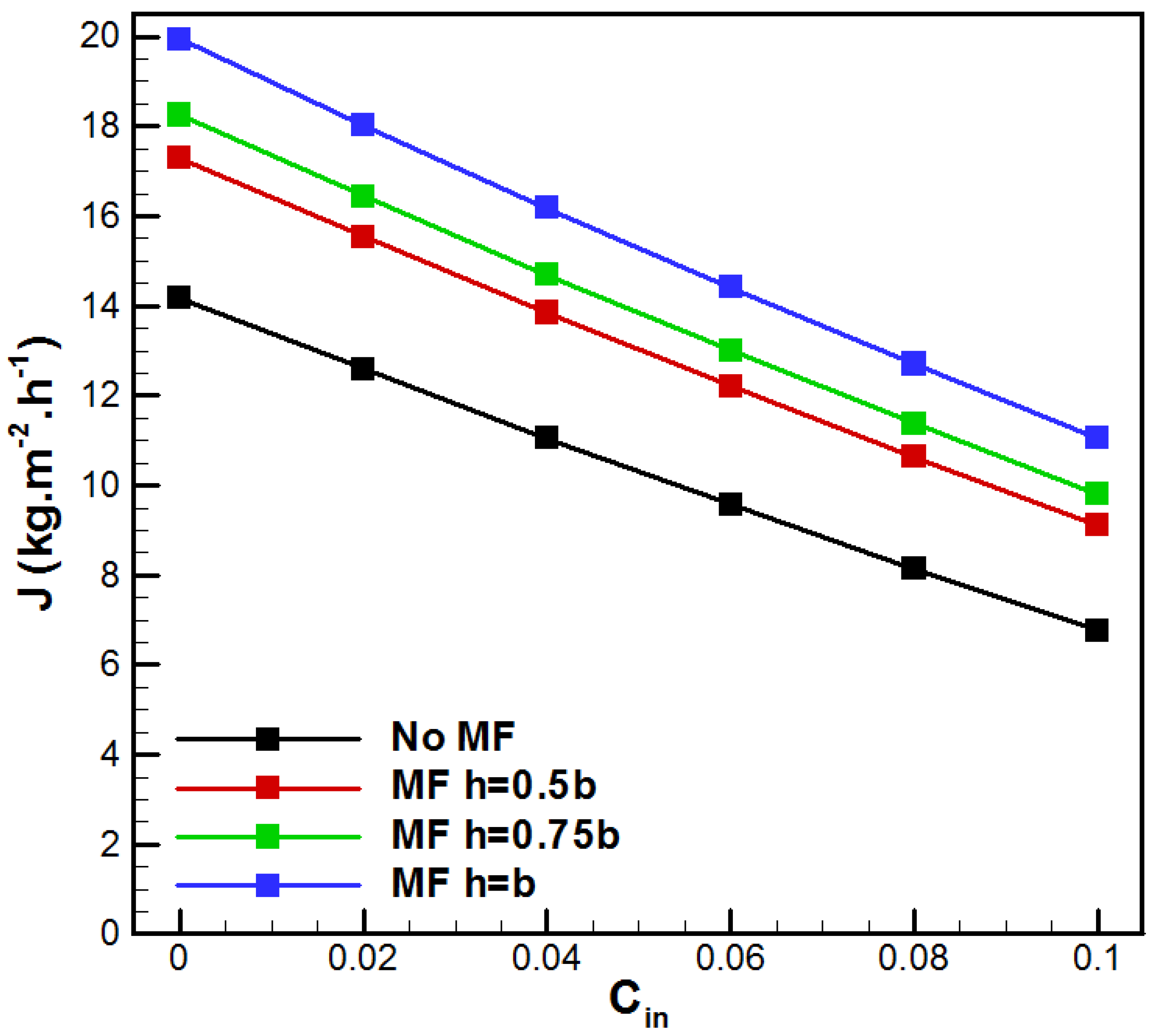

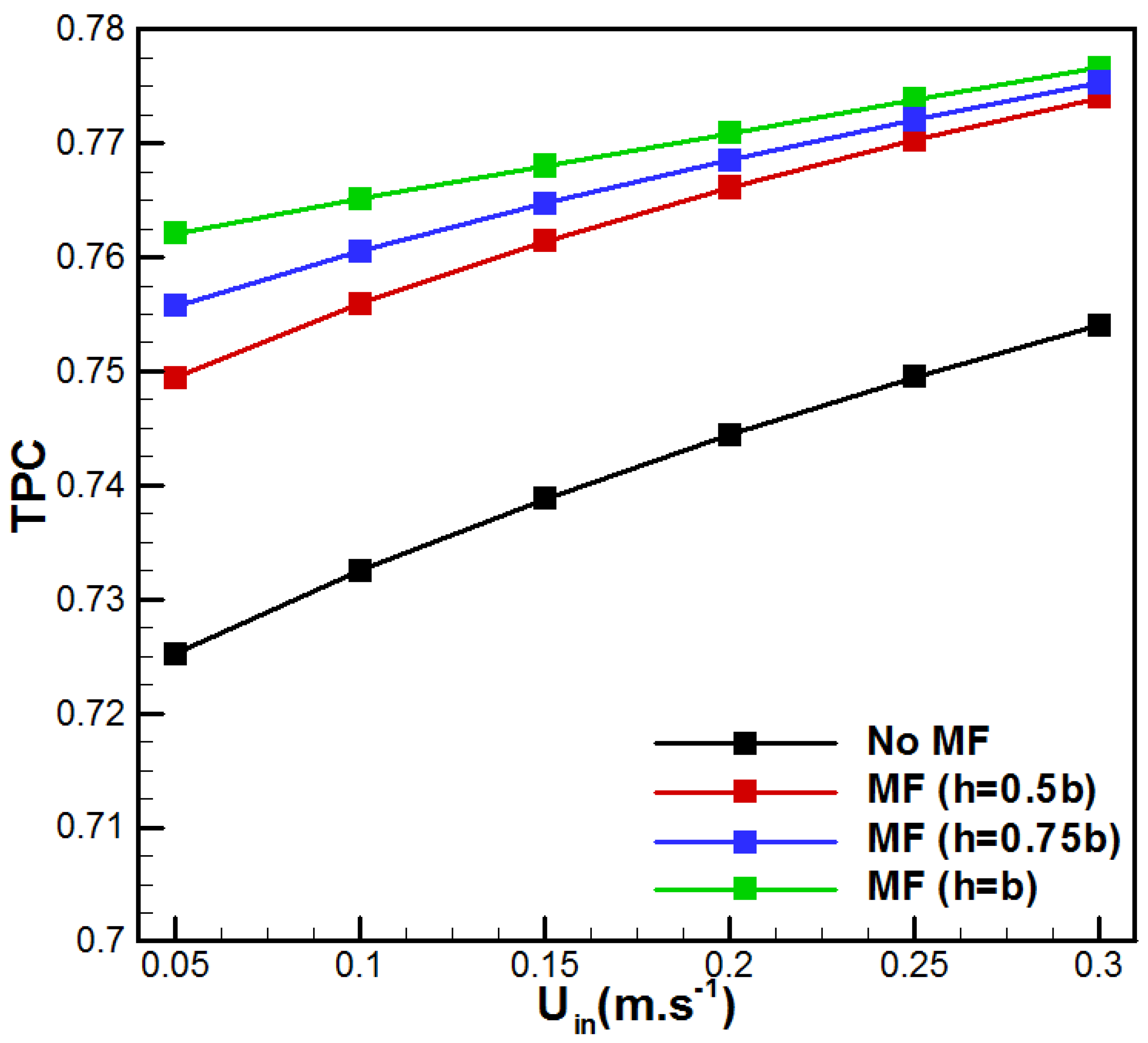

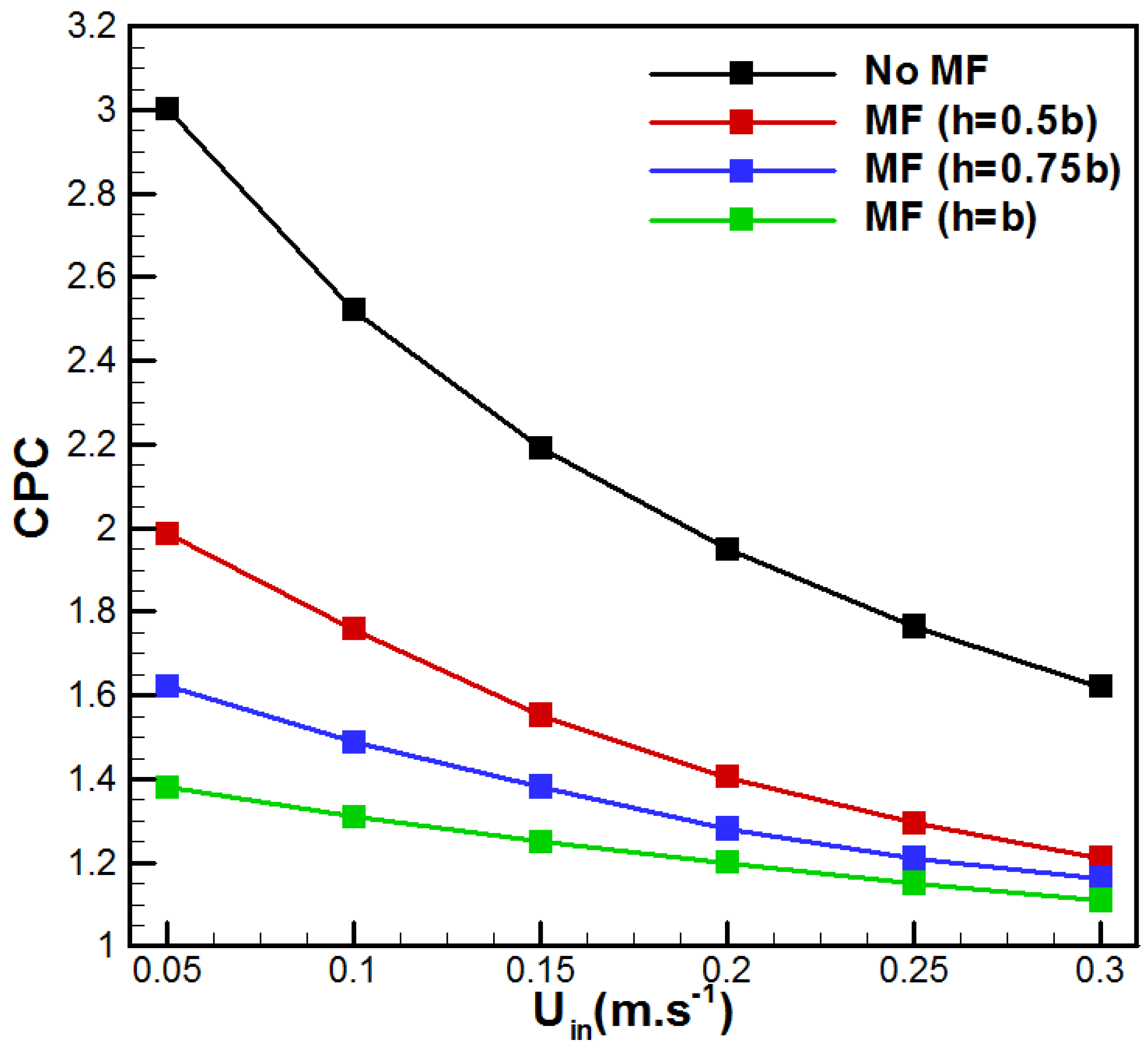

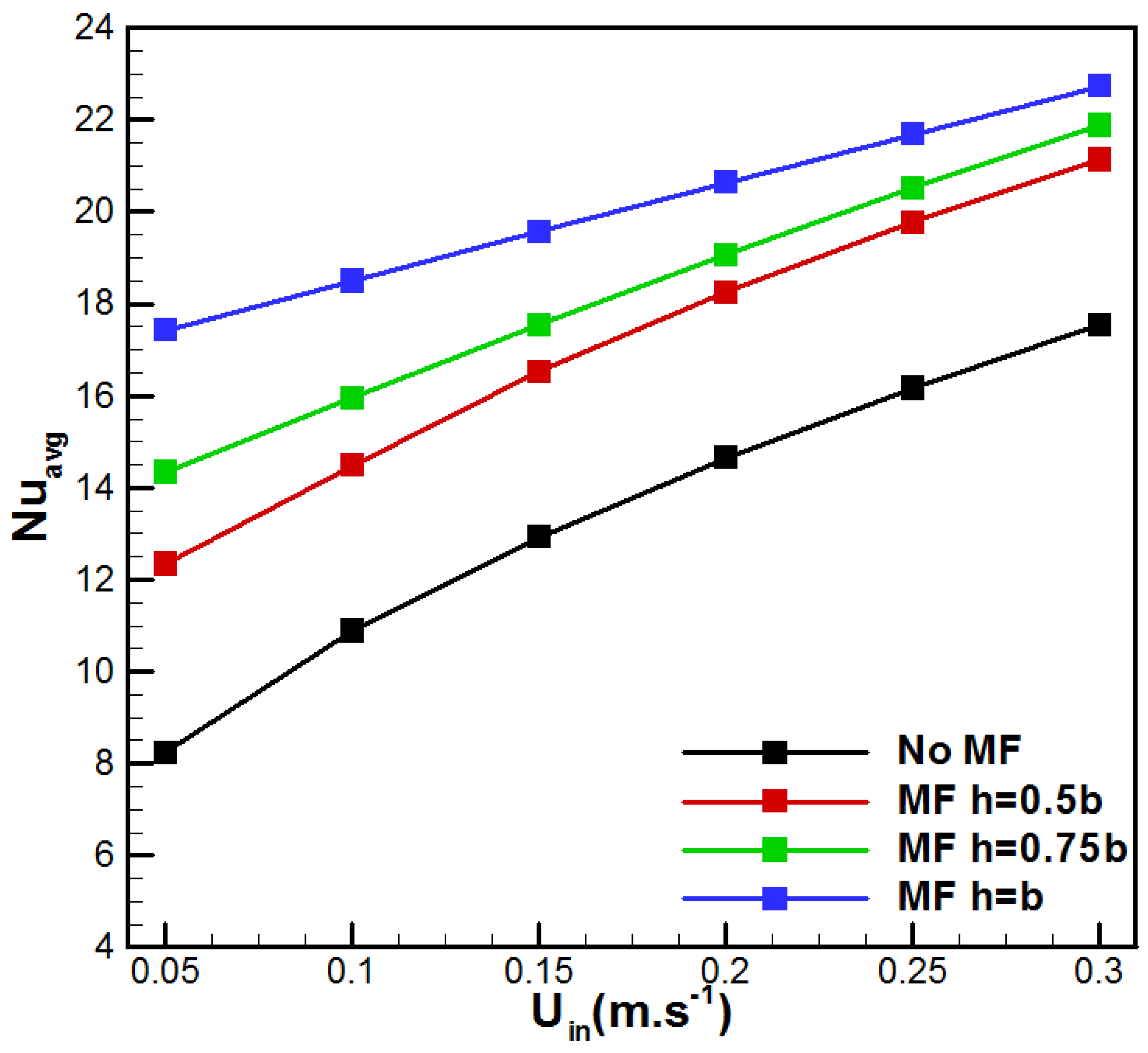

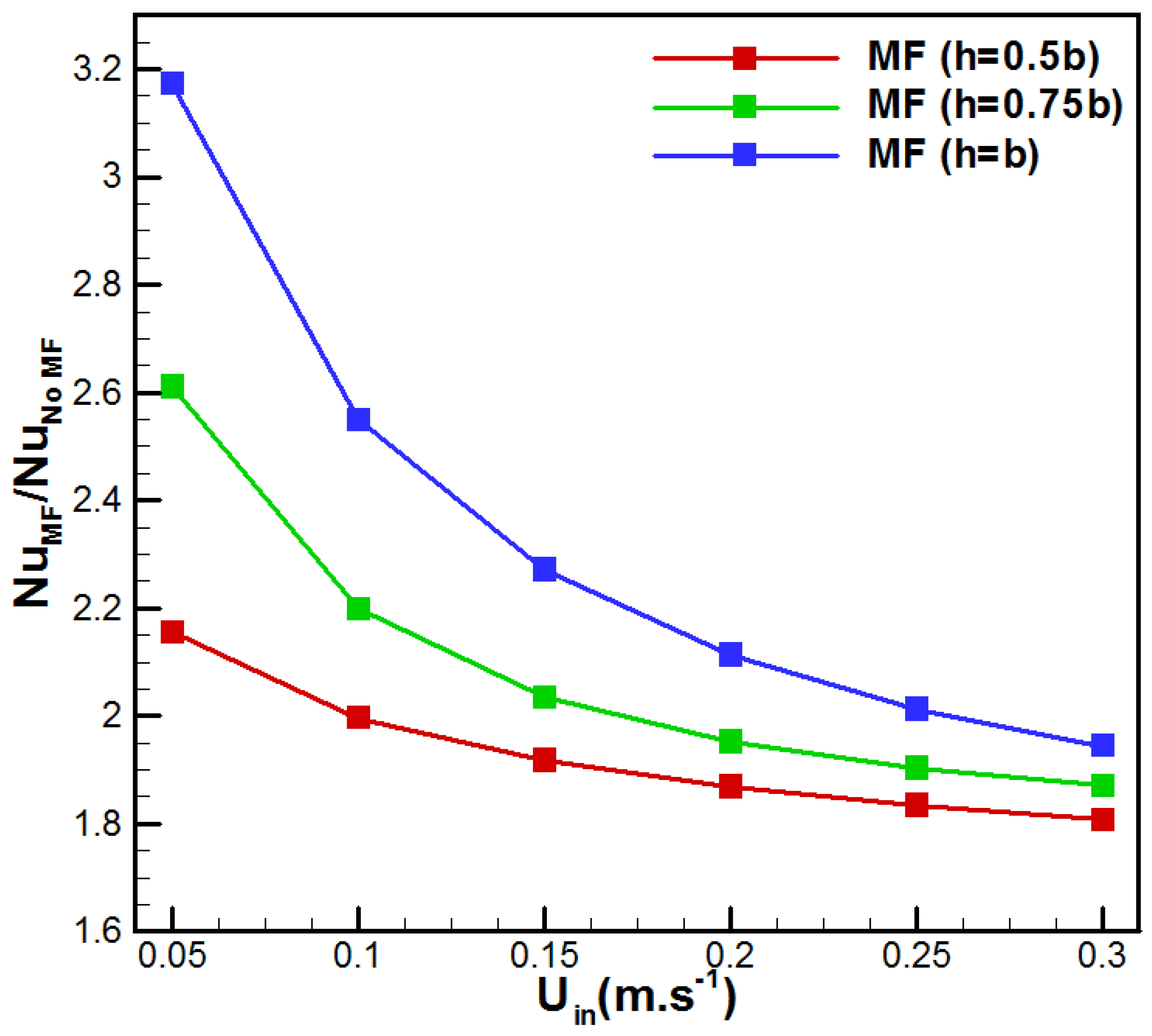

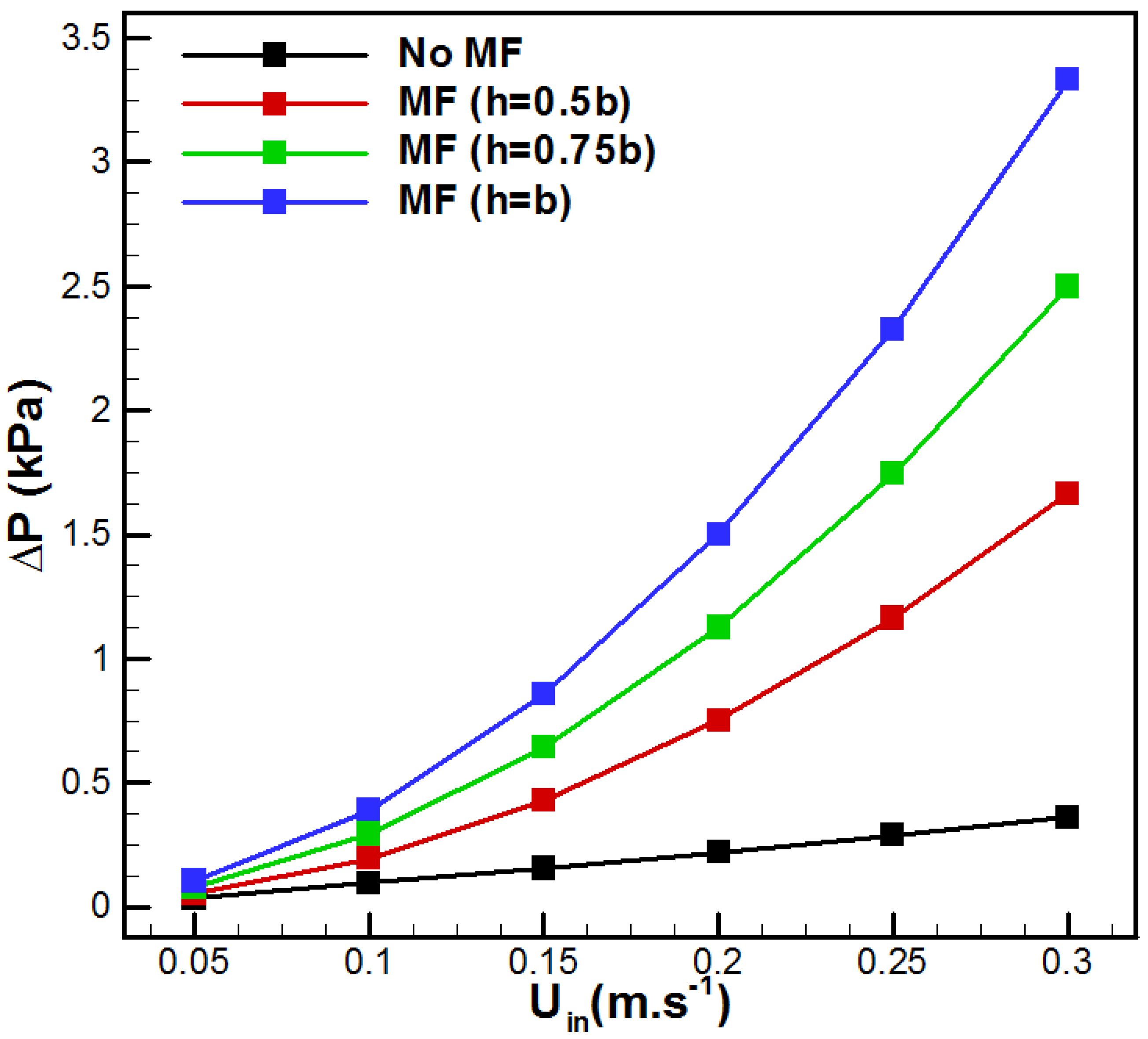

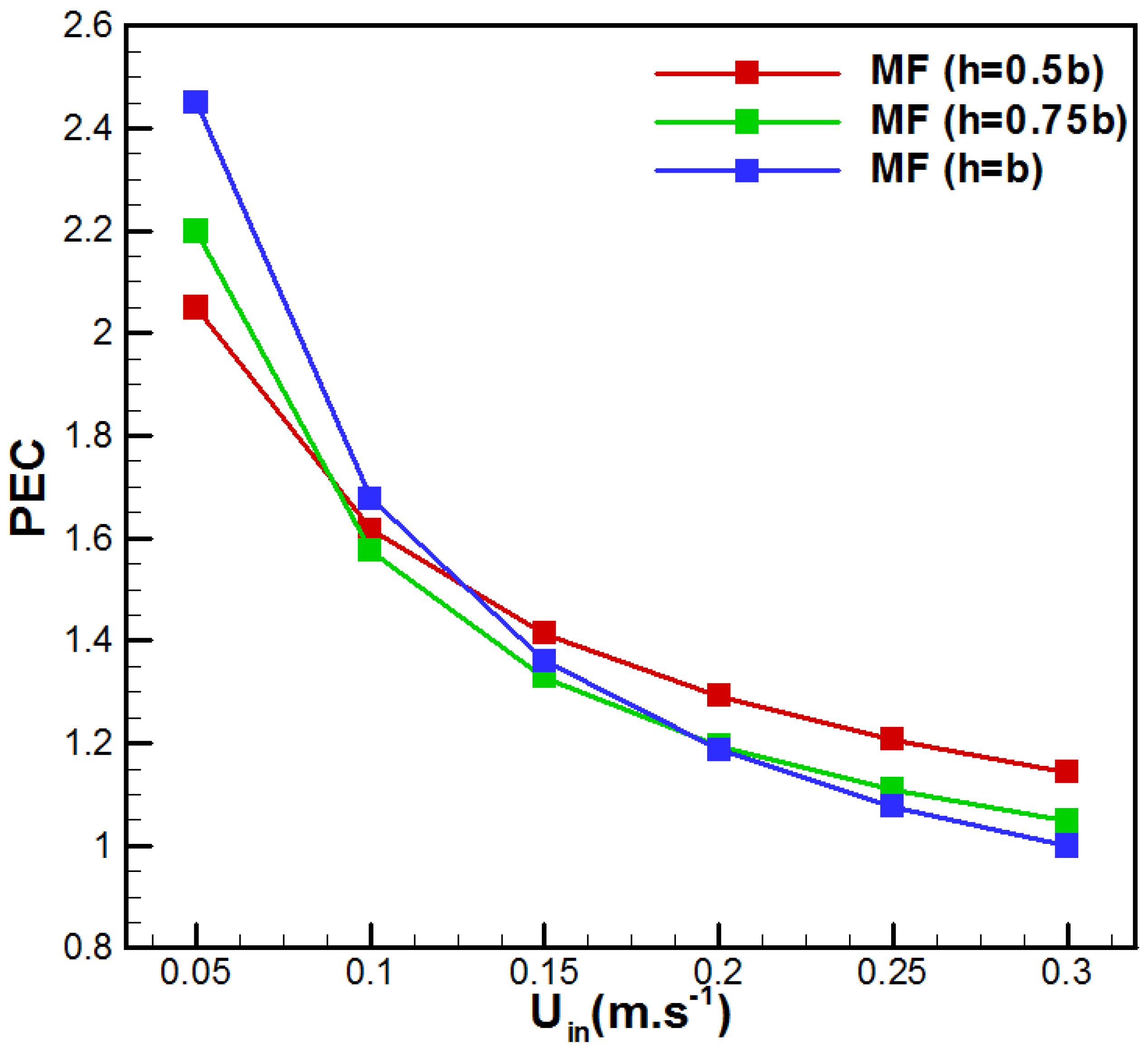

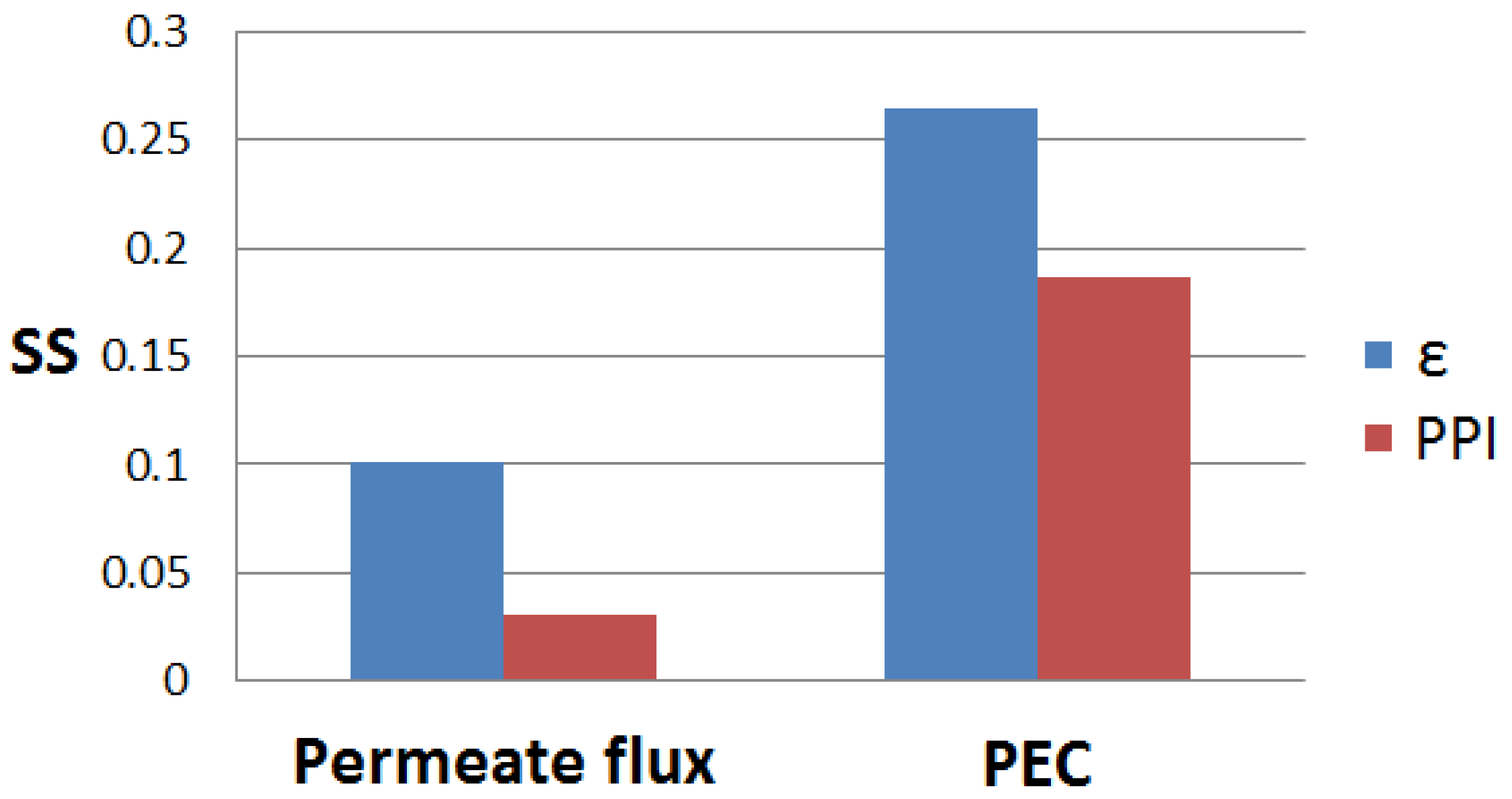

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nthunya, L.N.; Mamba, B.B. Membrane Distillation for Water Desalination: Assessing the Influence of Operating Conditions on the Performance of Serial and Parallel Connection Configurations. Membranes 2025, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, P.D.; Guangming, J.; Muttucumaru, S. A comprehensive review of vacuum membrane distillation: Applications, challenges, and future directions. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 78, 108779. [Google Scholar]

- Nthunya, L.N.; Chong, K.C.; Lai, S.O.; Lau, W.J.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Camacho, L.M.; Shirazi, M.M.A.; Ali, A.; Mamba, B.B.; Osial, M.; et al. Progress in membrane distillation processes for dye wastewater treatment: A review. Chemosphere 2024, 360, 142347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandro, F.; Macedonio, F. A Critical Review of Membrane Distillation Using Ceramic Membranes: Advances, Opportunities and Challenges. Materials 2025, 18, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaghini, C.M.E.; Garcez, J.; Hoff, R.; Ambrosi, A.; Rezzadori, K. Addressing Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Aquaculture: A Vacuum Membrane Distillation Approach. Membranes 2025, 15, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, A.; Mana, T.; Ali, E.; Al-Ansary, H.; Almehmadi, F.A.; Alhoshan, M. Experimental Investigation on the Energy and Exergy Efficiency of the Vacuum Membrane Distillation System with Its Various Configurations. Membranes 2024, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Ziapour, B.M.; Ghaebi, H.; Nematollahzadeh, A. Simulation of vacuum membrane desalination within an enhanced design of compact solar water heaters. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 257, 124243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspar, J.; Xue, G.; Oztekin, A. Performance characteristics on up-scaling vacuum membrane distillation modules. Desalination 2024, 569, 116994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanasiou, A.; Angistali, K.; Plakas, K.V.; Kostoglou, M.; Karabelas, A.J. Ammonia recovery from anaerobic-fermentation liquid digestate with vacuum membrane distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 314, 123602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, O.; Zelal, I.; Nadir, D. Acetic acid and methanol recovery from dimethyl terephthalate process wastewater using pressure membrane and membrane distillation processes. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 38, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Lan, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Ye, C.; Lin, J. Pilot-scale vacuum membrane distillation for decontamination of simulated radioactive wastewater: System design and performance evaluation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 275, 119129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwatban, A.M.; Alhazmi, M.A.; Aljumaily, M.M.; Alsalhy, Q.F. Computational fluid dynamics simulations of desalination processes in vacuum membrane distillation. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabkesh, Y.; Fattahi, M.S.; Mohammadi, T. A study on effect of stearic acid-modified cellulose nanocrystals on morphology and performance of PVDF membranes in vacuum membrane distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 382, 135961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Han, D.; Xiang, J. Experimental investigation on the mechanical vapor recompression evaporation system coupled with multiple vacuum membrane distillation modules to treat industrial wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 275, 119178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawad, S.M.; Shamet, O.; Lawal, D.; Khalifa, A.E. Multiple vapor compressors for enhanced performance and cost savings in vacuum membrane distillation. Next Sustain. 2025, 6, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladi, R.; Hadrich, B.; Frikha, N.; Gabsi, S. Comparative Analysis of Energy Recovery Configurations for Solar Vacuum Membrane Distillation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Deng, D.; Li, Z.; Xiang, J. Performance Comparison of Vertical and Horizontal Vacuum Membrane Distillation Module Coupled with Mechanical Vapor Recompression. Desalination 2024, 569, 117039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, M.; Khalifa, A. Novel Vacuum Membrane Distillation Operated by Air Ejector and Bubble Column Dehumidifier for Sustainable Water Desalination—Energetic, Exergetic, and Economic Analysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 371, 133368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anqi, A.E.; Usta, M.; Krysko, R.; Lee, J.-G.; Ghaffour, N.; Oztekin, A. Numerical Study of Desalination by Vacuum Membrane Distillation—Transient Three-Dimensional Analysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 596, 117609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Kim, W.S. Numerical Study on Multi-Stage Vacuum Membrane Distillation with Economic Evaluation. Desalination 2014, 339, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Hock, E.M.V.; Municchi, F.; Tilton, N.; Cath, T.Y.; Turchi, C.S.; Heeley, M.B.; Jassby, D. Multistage Surface-Heated Vacuum Membrane Distillation Process Enables High Water Recovery and Excellent Heat Utilization: A Modeling Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Manas, J.A.; Ruiz-Aguirre, A.; Acién, F.G.; Zaragoza, G. Assessment of a Pilot System for Seawater Desalination Based on Vacuum Multi-Effect Membrane Distillation with Enhanced Heat Recovery. Desalination 2018, 443, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Han, D.; Gu, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y. Exergy Analysis of a Vacuum Membrane Distillation System Integrated with Mechanical Vapor Recompression for Sulfuric Acid Waste Treatment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 178, 115516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mericq, J.-P.; Laborie, S.; Cabassud, C. Evaluation of Systems Coupling Vacuum Membrane Distillation and Solar Energy for Seawater Desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubha, T.C.; Kotresha, B.; Sheemandanavar, M.S. Exergy and Entropy Analysis of Metal Foams Based on the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 245, 122886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavar, A.; Shahmohammadi, M.; Siavashi, M. CPU Cooling with a Water-Based Heatsink Filled with Multi-Layered Porous Metal Foam: Hydrothermal and Entropy Generation Analysis. J. Cent. South Univ. 2023, 30, 3641–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.H.; Saihood, R.G. Experimental Study on the Performance of Gradient Pores Density Metal Foam in a Rectangular Channel. Heat Transf. 2025, 54, 2688–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrofarakh, M.; Shahouni, R.; Moghadam, H.; Samimi, M. CFD Analysis of Heat and Mass Transfer in Hollow Fiber DCMD Enhanced by Metal Foam. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrofarakh, M. Investigation of Performance and Entropy Generation Rate of Direct Contact Membrane Distillation with Metal Foam: A CFD Study. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 50, 3869–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loussif, N.; Orfi, J. A Comparative Study of Membrane Properties Modeling Used in Vacuum Membrane Distillation Theoretical Studies. Membr. Water Treat. 2025, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav, P.H.; Gnanasekaran, N.; Perumal, D.A.; Mobedi, M. Performance Evaluation of Partially Filled High-Porosity Metal Foam Configurations in a Pipe. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 194, 117081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, H.R.; Sharifi, A.E. Application of Multilayered Porous Media for Heat Transfer Optimization in Double Pipe Heat Exchangers Using Neural Network and NSGA-II. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousri, A.; Hamadouche, A.; Khali, S.; Nebbali, R.; Beji, M. Forced Convection Cooling of Multiple Heat Sources Using Open-Cell Metal Foams. J. Therm. Eng. 2020, 7, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhadef, K.; Chikh, S. Mass Transfer Analysis in an Intermittently Porous Channel. Sci. Technol. 2003, 19, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Loussif, N.; Orfi, J. Heat and Mass Transfer in Sweeping Gas Membrane Distillation. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 131, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, G.; Guan, G.; Wang, R. Numerical Modeling and Optimization of Vacuum Membrane Distillation Module for Low-Cost Water Production. Desalination 2014, 339, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loussif, N.; Orfi, J.; Ali, E. Desalination by Vacuum Membrane Distillation: A Numerical Study on the Effect of Heat Transfer Correlations and Slip Flow. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfi, J.; Loussif, N. Modeling of a Membrane Distillation Unit for Desalination. In Desalination: Methods, Costs and Technology; Nova Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 143–174. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.S.; Ooi, B.S.; Ahmad, A.L.; Leo, C.P.; Lau, W.J. Numerical Study on Performance and Efficiency of Batch Submerged Vacuum Membrane Distillation for Desalination. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 163, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Fane, A.G.; Li, X. Desalination by Membrane Distillation Adopting a Hydrophilic Membrane. Desalination 2005, 173, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursharif, Z.; Salarian, H.; Javaherdeh, K.; Nimvari, M.E. Numerical Simulation of Heat Transfer on Nanofluid Flow in an Annular Pipe with Simultaneous Embedding of Porous Discs and Triangular Fins. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 2021, 44, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džijan, I.; Virag, Z.; Krizmanić, S. Comparison of the SIMPLER and the SIMPLE Algorithm for Solving Navier–Stokes Equations on Collocated Grids. Trans. FAMENA 2006, 30, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Yun, T.; Hong, S.; Lee, S. Experimental and Theoretical Investigation of a High-Performance PTFE Membrane for Vacuum Membrane Distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 617, 118524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.; Nam, S.-H.; Hwang, T.-M.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y. Effect of Operating Parameters on Temperature and Concentration Polarization in Vacuum Membrane Distillation. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 54, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmad, A.A.; Dukhan, N. Cooling Design for PEM Fuel-Cell Stacks Employing Air and Metal Foam: Simulation and Experiment. Energies 2021, 14, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Vanneste, J.; Decaluwe, S.C.; Cath, T.Y.; Tilton, N. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations of Polarization Phenomena in Direct Contact Membrane Distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 591, 117150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, J.M.; Asiri, M.M.; Caspar, J.; Oztekin, A. The performance of hollow fiber direct contact membrane distillation modules. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 319, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, C.; Shi, F.; Ni, X. Local and Global Sensitivity Analysis of Key Durability Parameters of Concrete under Chloride Environment. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Khan, W.A.; Gul, R.; Dayyan, B.; Zubair, M. Hydrodynamics and Sensitivity Analysis of a Williamson Fluid in Porous-Walled Wavy Channel. Comput. Mater. Continua 2021, 68, 3877–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Membrane | PVDF [30] | Metal Foam | Aluminum [31] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal pore size (μm) | 0.22 | Pores per inch, PPI | 45 |

| Thickness (μm) | 125 | Porosity | 0.9 |

| Porosity | 0.75 | Permeability K (m2) | 0.420 × 10−7 |

| Nx, Ny | 700, 40 | 800, 40 | 700, 50 | 800, 50 |

| J [kg/m2h] | 17.110 | 17.111 | 17.110 | 17.112 |

| Nuavg | 10.228 | 10.231 | 10.229 | 10.230 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loussif, N.; Orfi, J. Effects of Metal Foam Insertion on the Performance of a Vacuum Membrane Distillation Unit. Membranes 2025, 15, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120379

Loussif N, Orfi J. Effects of Metal Foam Insertion on the Performance of a Vacuum Membrane Distillation Unit. Membranes. 2025; 15(12):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120379

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoussif, Nizar, and Jamel Orfi. 2025. "Effects of Metal Foam Insertion on the Performance of a Vacuum Membrane Distillation Unit" Membranes 15, no. 12: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120379

APA StyleLoussif, N., & Orfi, J. (2025). Effects of Metal Foam Insertion on the Performance of a Vacuum Membrane Distillation Unit. Membranes, 15(12), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120379