Analysis of Fouling in Hollow Fiber Membrane Distillation Modules for Desalination Brine Reduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feed Water (Desalination Brine)

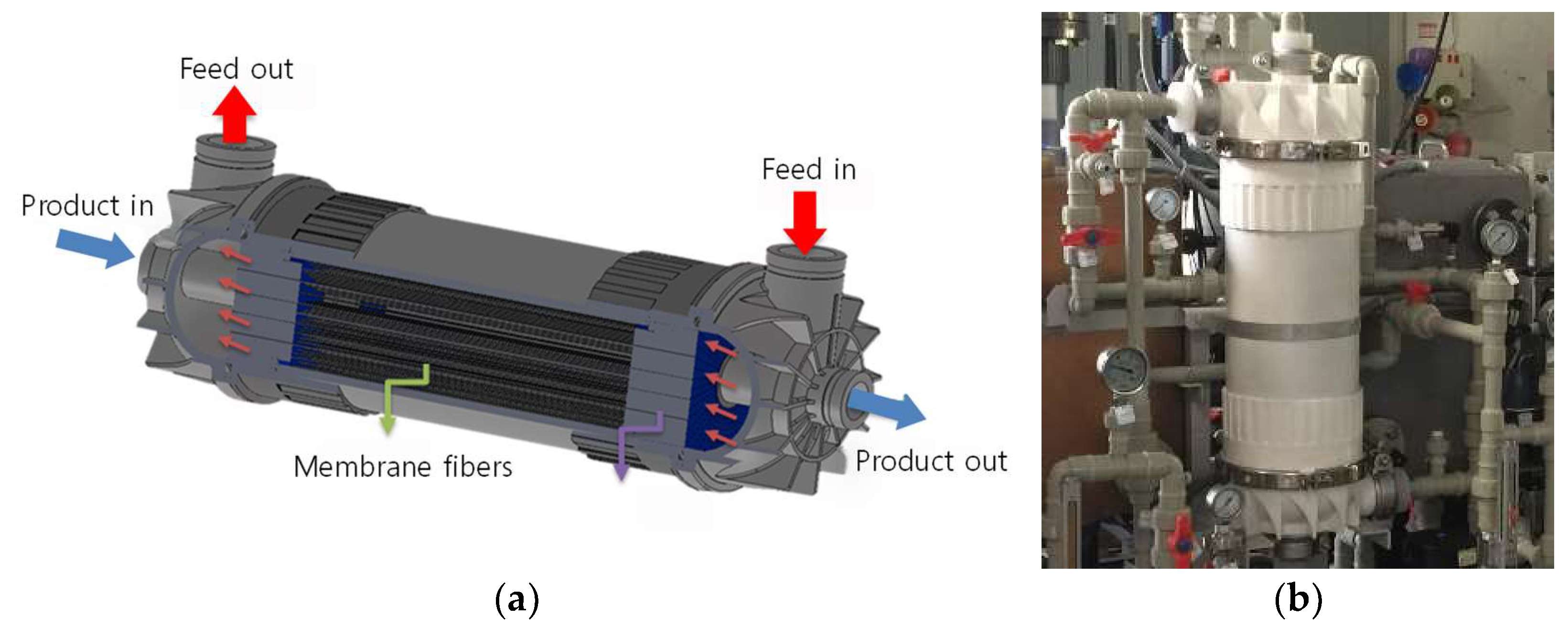

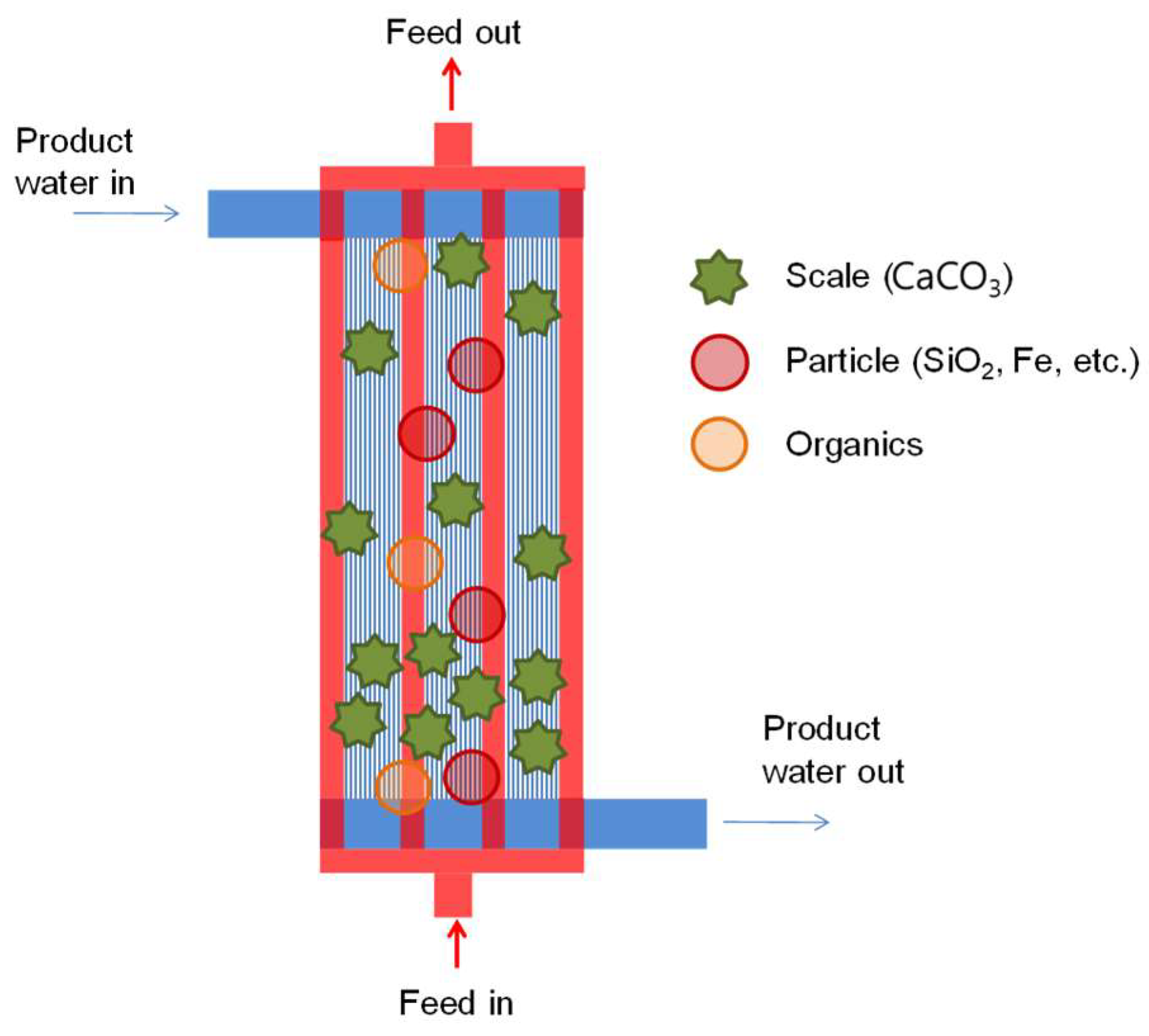

2.2. MD Module

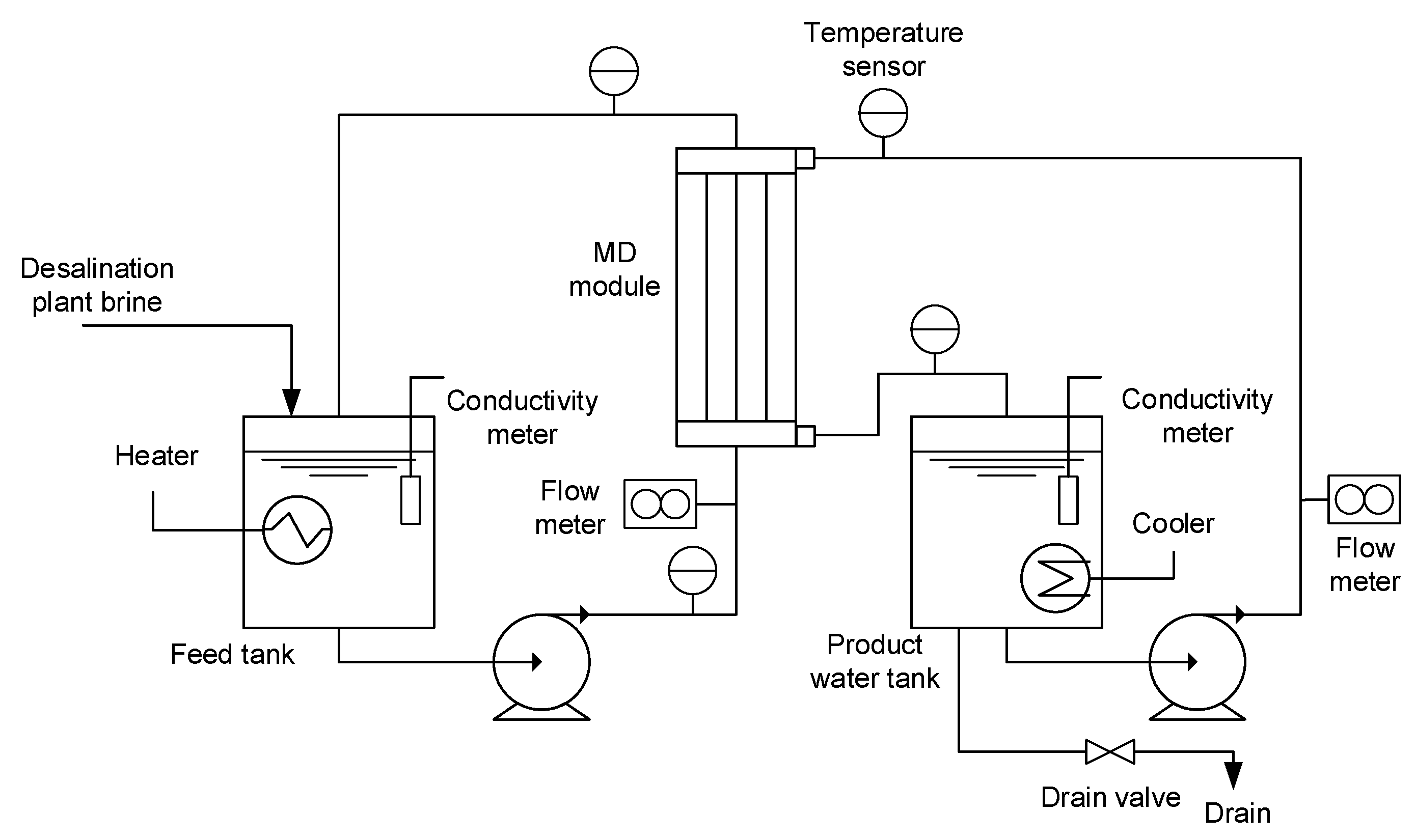

2.3. MD Pilot Plant

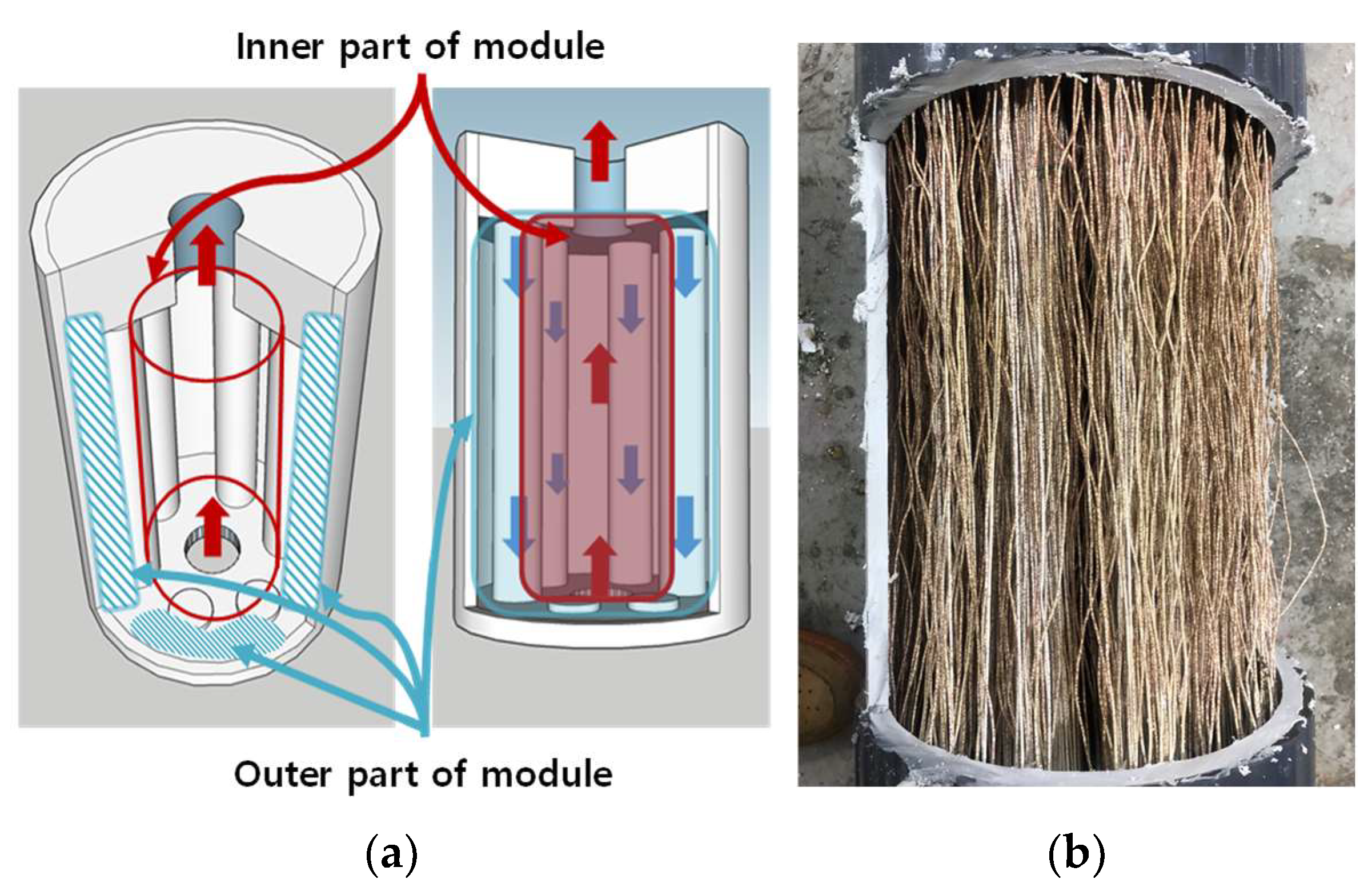

2.4. Membrane Autopsy

2.5. Analytic Methods

3. Results and Discussion

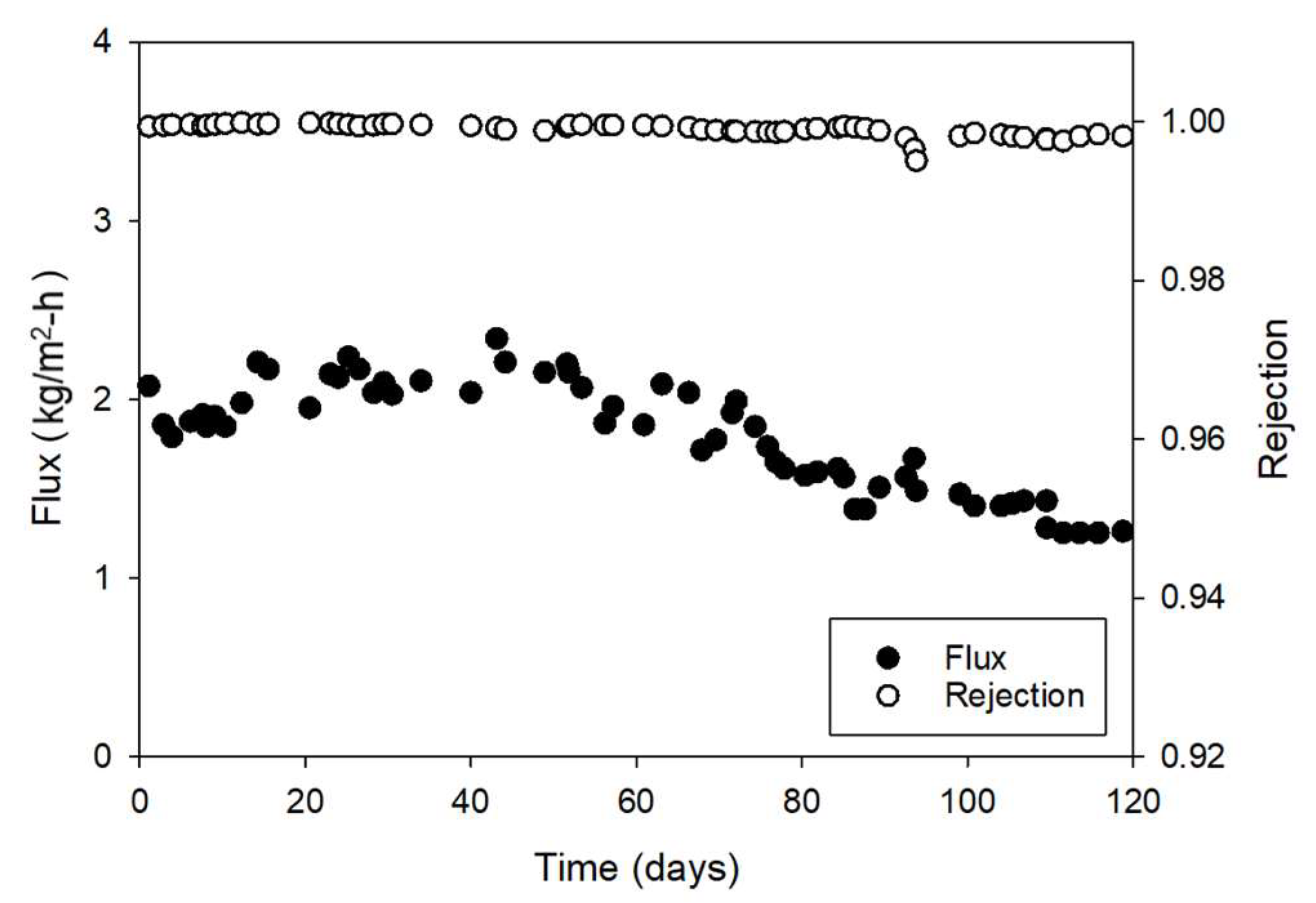

3.1. Performance of the MD Module During the Long-Term Operation

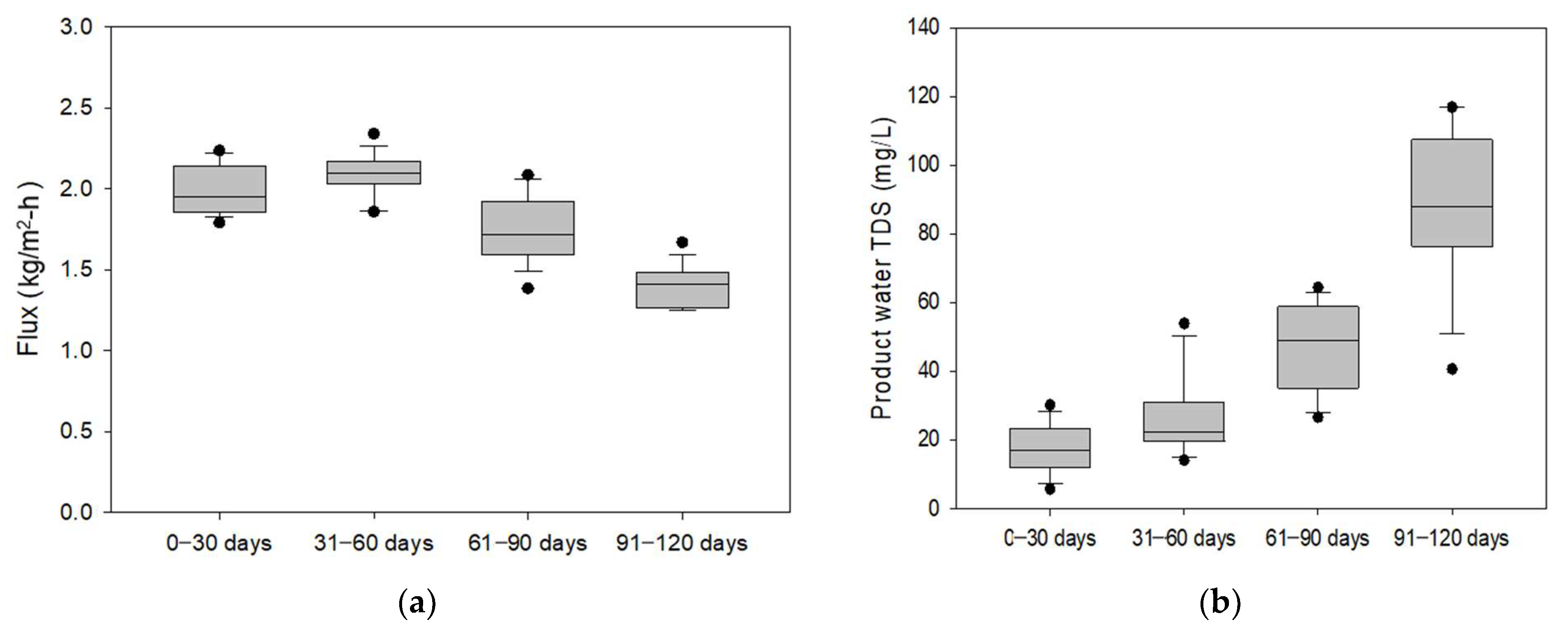

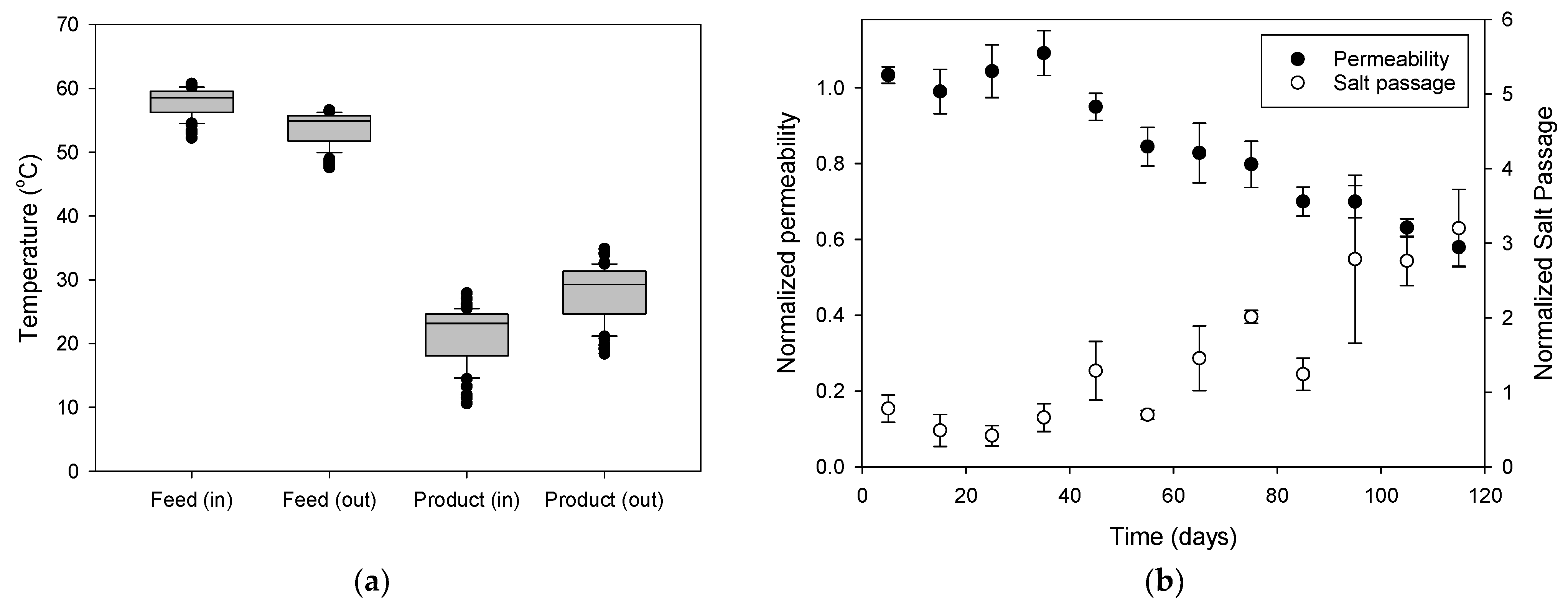

3.1.1. Temporal Variations in Flux and Rejection

3.1.2. Comparison of Flux and Product Water TDS

3.1.3. Analysis of Water Permeability and Salt Passage

3.2. Changes in Physical Properties of the Membrane After Long-Term Operation

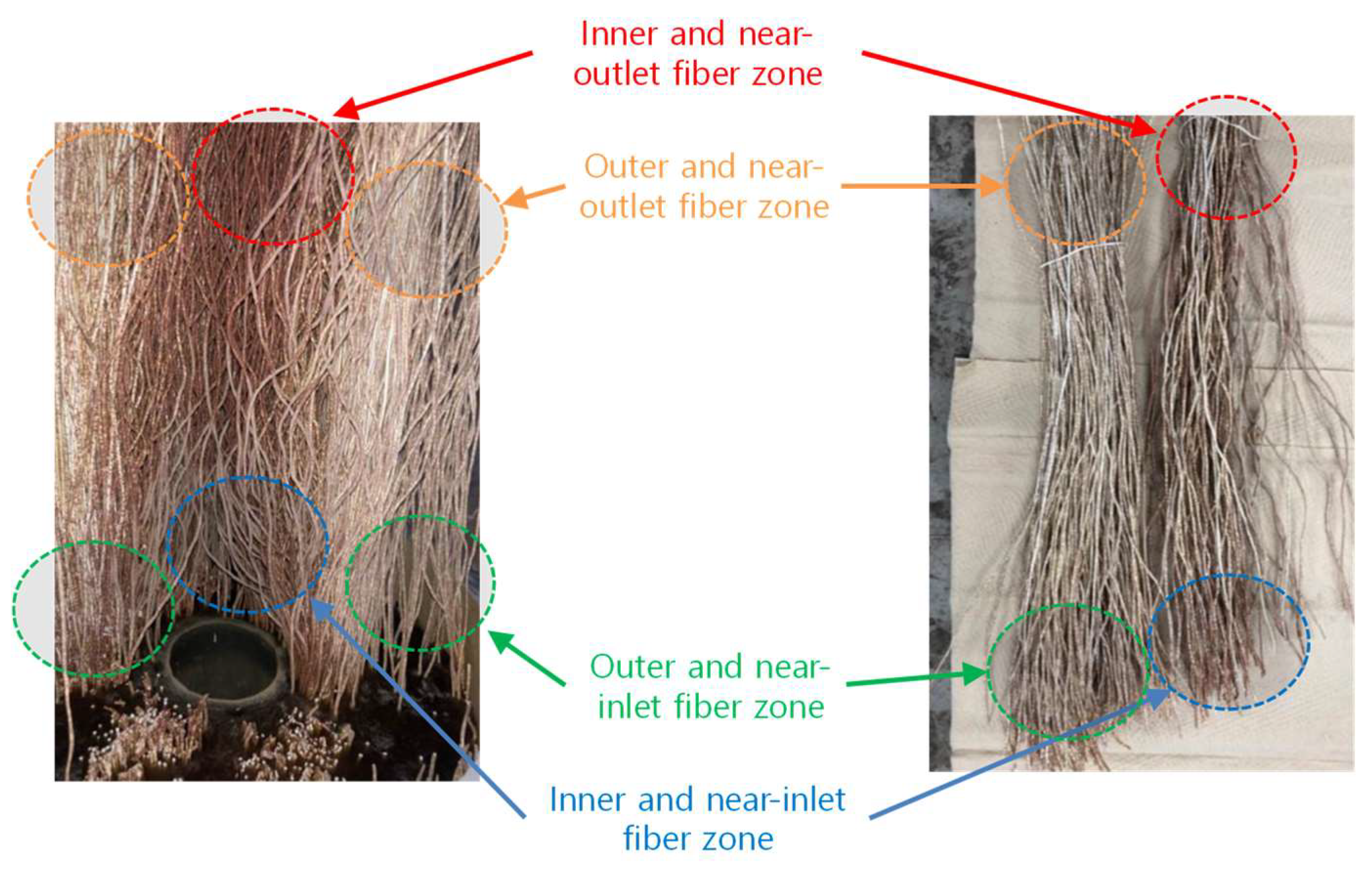

3.2.1. Visual Observation of Foul Distribution Within the Module

3.2.2. Comparison of Contact Angles and Liquid Entry Pressure

3.2.3. Comparison of Tensile Strength of Membrane Fibers

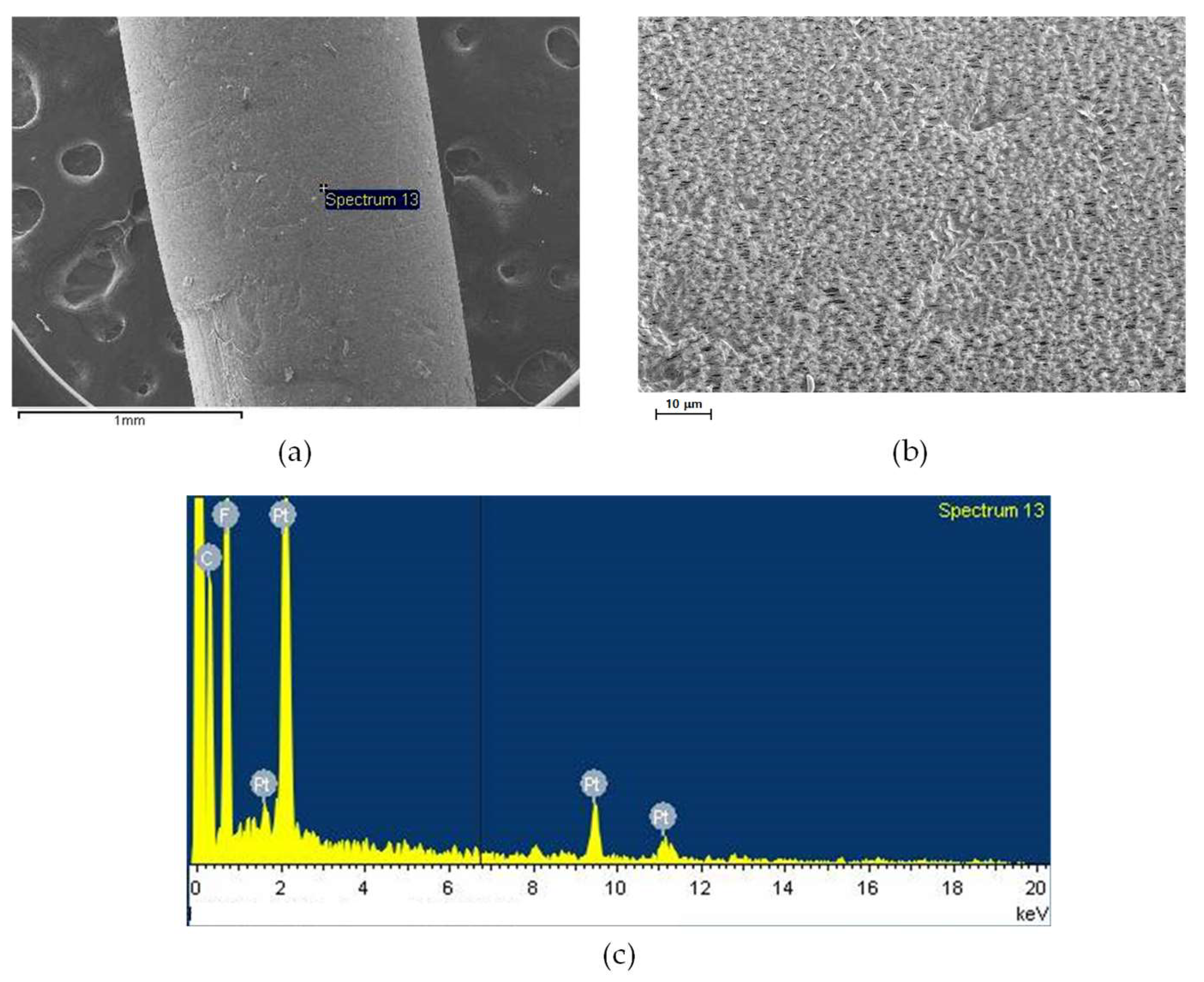

3.3. Morphological and Compositional Analysis of Fouled Membranes

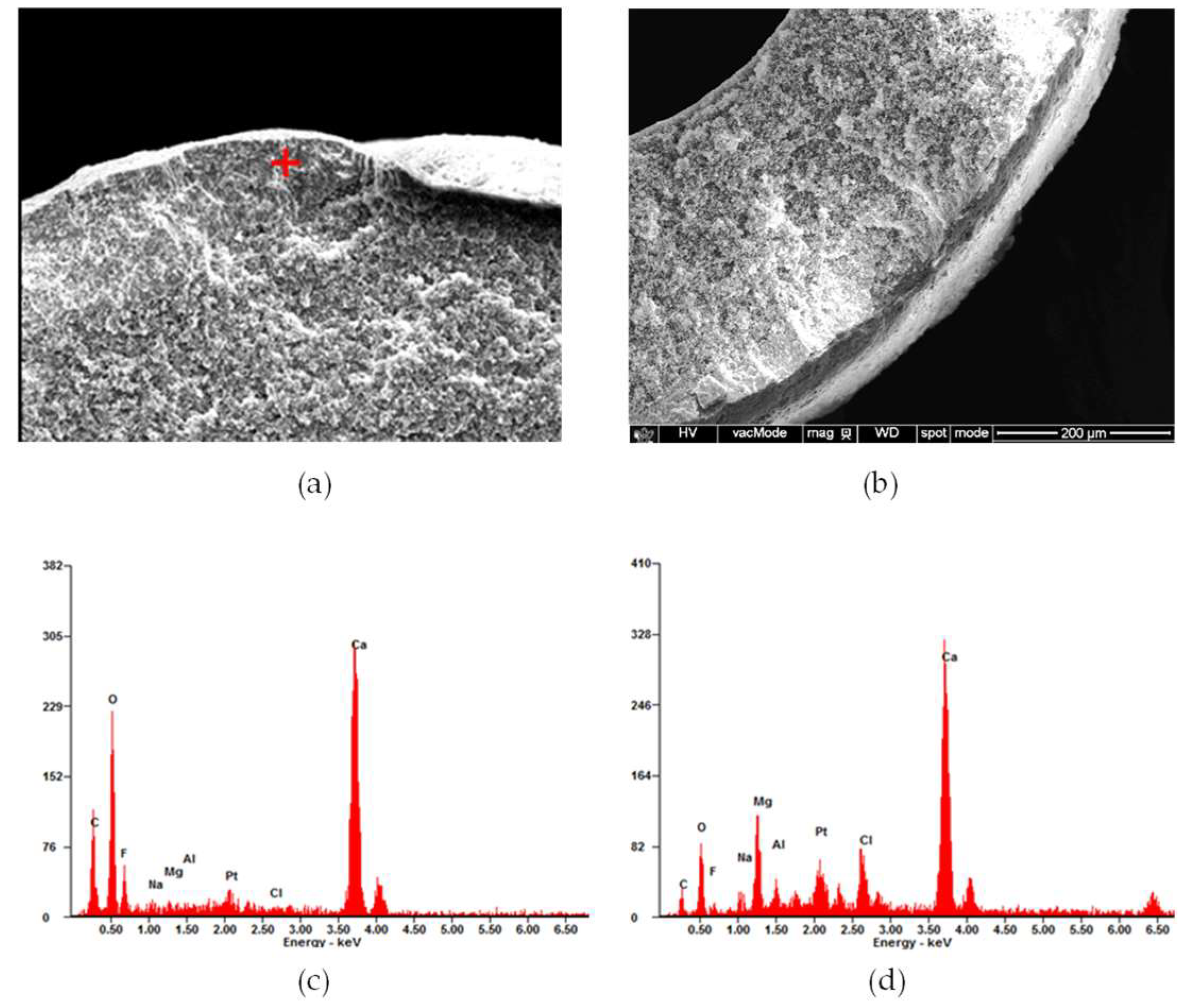

3.3.1. SEM Analysis

3.3.2. Compositional Analysis

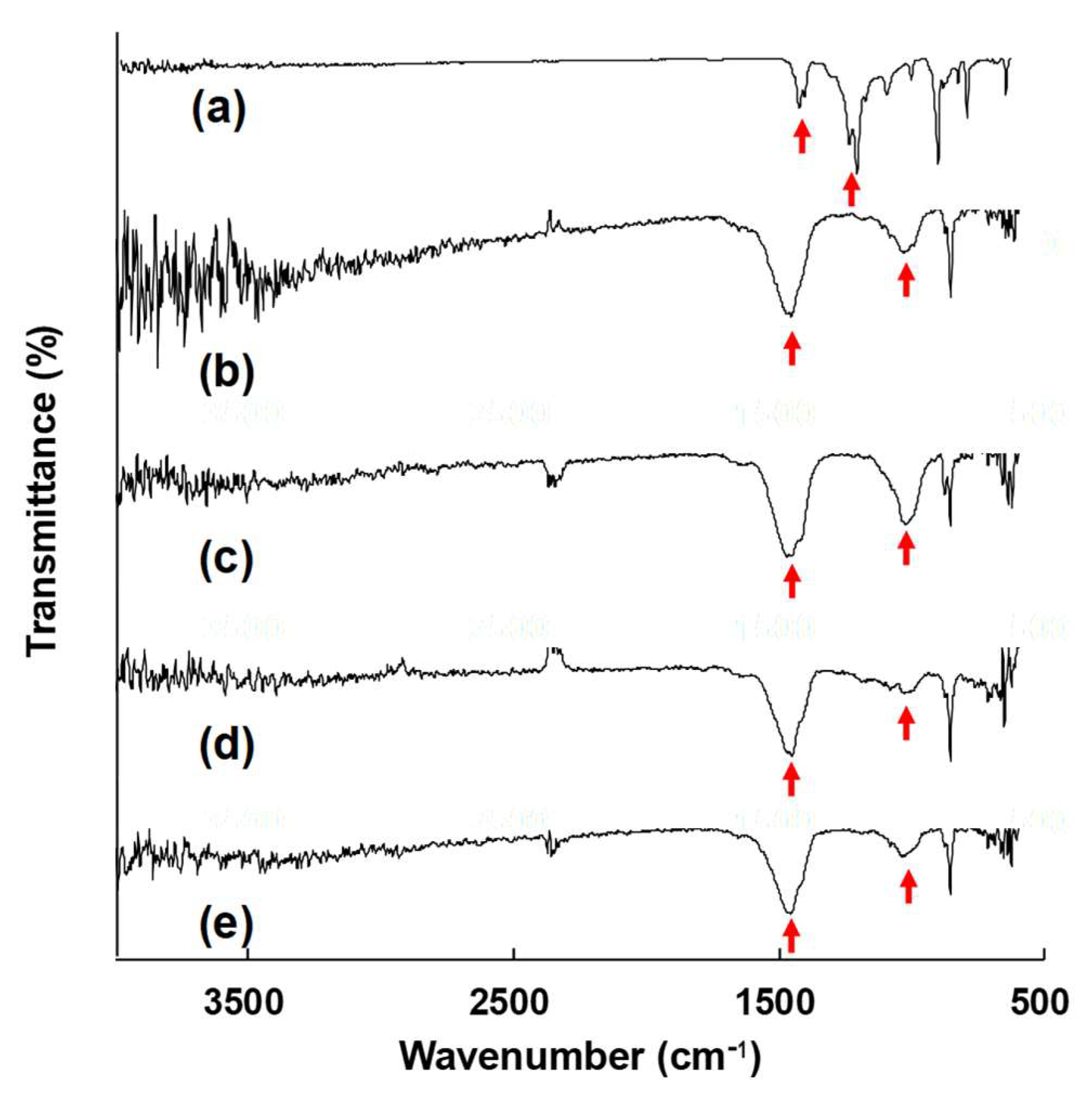

3.3.3. FT-IR Analysis

3.4. Proposed Mechanism of MD Module Fouling and Wetting

4. Conclusions

- The DCMD module treating real MED brine maintained >99% salt rejection over 120 days, while flux and permeability declined due to progressive fouling and partial wetting.

- Autopsy identified CaCO3 scaling as the dominant deposit, with minor SiO2/Fe particulates and trace organics; SEM/EDS, ICP-OES, and FT-IR provided consistent evidence.

- Fouling was spatially non-uniform—most severe near the inlet and inner fibers—where higher local temperature and weaker mixing promoted supersaturation and deposition.

- Deposits reduced surface hydrophobicity and LEP, corroborating a scaling-enabled wetting pathway linked to performance loss.

- The results highlight the need for improved hydrodynamic design, targeted pretreatment/antiscalants, and carbonate-oriented cleaning to sustain long-term operation; future work will evaluate anti-scaling membranes, optimized flow channels, and hybrid MD configurations for robust brine management.

- To ensure reliability and reproducibility, multiple parallel membrane modules should be tested simultaneously to minimize inaccuracies in conclusions caused by experimental deviations. Accordingly, future work will include parallel module testing to statistically validate the observed spatial fouling trends.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MD | Membrane Distillation |

| DCMD | Direct Contact Membrane Distillation |

| VMD | Vacuum Membrane Distillation |

| SWRO | Seawater Reverse Osmosis |

| MED | Multi-effect Distillation |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| LEP | Liquid Entry Pressure |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDS | Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene Fluoride |

| ZLD | Zero Liquid Discharge |

References

- Ogunbiyi, O.; Saththasivam, J.; Al-Masri, D.; Manawi, Y.; Lawler, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Sustainable brine management from the perspectives of water, energy and mineral recovery: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2021, 513, 115055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J.; Park, Y.-G.; Shon, H.; Ahn, C.H.; Kim, S.-H. Hybrid desalination processes for beneficial use of reverse osmosis brine: Current status and future prospects. Desalination 2019, 454, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, J.P.M.; Amaral, M.C.S.; de Lima, S.C.R.B. Sustainable water management in the mining industry: Paving the way for the future. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 71, 107239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.H.S.; Fernandes, L.F.S.; Moura, J.P.; Oliveira, M.D.d.; Akabassi, L.; Pacheco, F.A.L. A framework for analyzing seawater intrusion in coastal areas: An adapted GALDIT model application for Espírito Santo, Brazil. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, I.; Carratalá, A.; Pereira-Rojas, J.; Díaz, M.J.; Rodríguez-Rojas, F.; Sánchez-Lizaso, J.L.; Sáez, C.A. Assessment of brine discharges dispersion for sustainable management of SWRO plants on the South American Pacific coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 207, 116905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Baddour, R.E. A review of sources, effects, disposal methods, and regulations of brine into marine environments. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 87, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, S.; Rosso, D.; Yeh, W.W.G. Optimal planning and design of seawater RO brine outfalls under environmental uncertainty. Desalination 2014, 333, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, N.; Paytan, A.; Potts, D.C.; Haddad, B.; Lykkebo Petersen, K. Management preferences and attitudes regarding environmental impacts from seawater desalination: Insights from a small coastal community. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 163, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevah, Y. 1.4–-Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Regional Cooperation in the Middle East. In Comprehensive Water Quality and Purification; Ahuja, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 40–70. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, J.; Wilder, M. Discourse and desalination: Potential impacts of proposed climate change adaptation interventions in the Arizona–Sonora border region. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatiki, K.; de Jonge, N.; Nielsen, J.L.; Scholz, B.; Avramidi, E.; Lymperaki, M.; Hesselsøe, M.; Xevgenos, D.; Küpper, F.C. Environmental impact of brine from desalination plants on marine benthic diatom diversity. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 210, 107207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariah, L.; Buckley, C.A.; Brouckaert, C.J.; Curcio, E.; Drioli, E.; Jaganyi, D.; Ramjugernath, D. Membrane distillation of concentrated brines e role of water activities in the evaluation of driving force. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 280, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashoor, B.B.; Mansour, S.; Giwa, A.; Dufour, V.; Hasan, S.W. Principles and applications of direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD): A comprehensive review. Desalination 2016, 398, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane distillation: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drioli, E.; Ali, A.; Macedonio, F. Membrane distillation: Recent developments and perspectives. Desalination 2015, 356, 56–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Pourafshari Chenar, M.; Sabzekar, M.; Ulbricht, M. Fabrication of durable superhydrophobic polypropylene membrane for hypersaline brine desalination using direct contact membrane distillation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanjuola, O.; Anis, S.F.; Hashaikeh, R. Enhancing DCMD vapor flux of PVDF-HFP membrane with hydrophilic silica fibers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 263, 118361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.-R.; Xing, Y.-L.; Wang, M.; An, Z.-H.; Zhao, H.-L.; Xu, K.; Qi, C.-H.; Yang, C.; Ramakrishna, S.; Liu, Q. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes as promising materials for developing high-performance desalination technologies. Desalination 2022, 528, 115639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavukkandy, M.O.; Chabib, C.M.; Mustafa, I.; Al Ghaferi, A.; AlMarzooqi, F. Brine management in desalination industry: From waste to resources generation. Desalination 2019, 472, 114187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zeid, M.A.E.-R.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.-L.; Hou, L. A comprehensive review of vacuum membrane distillation technique. Desalination 2015, 356, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaoui, K.; Ding, L.C.; Tan, L.P.; Mediouri, W.; Mahmoudi, F.; Nakoa, K.; Akbarzadeh, A. Sustainable Membrane Distillation Coupled with Solar Pond. Energy Procedia 2017, 110, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytaç, E.; Ahmed, F.E.; Aziz, F.; Khayet, M.; Hilal, N. A metadata survey of photothermal membranes for solar-driven membrane distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364, 132565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.; Amigo, J.; Suárez, F. Membrane distillation: Perspectives for sustainable and improved desalination. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Ji, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, P. Review of thermal efficiency and heat recycling in membrane distillation processes. Desalination 2015, 367, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minier-Matar, J.; Hussain, A.; Janson, A.; Benyahia, F.; Adham, S. Field evaluation of membrane distillation technologies for desalination of highly saline brines. Desalination 2014, 351, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Muñoz, R. Membranes– future for sustainable gas and liquid separation? Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Mavukkandy, M.O.; Loutatidou, S.; Arafat, H.A. Membrane distillation research & implementation: Lessons from the past five decades. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 189, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, N.A.; Zaliman, S.Q.; Leo, C.P.; Ahmad, A.L.; Ooi, B.S.; Poh, P.E. Electrochemical cleaning of superhydrophobic polyvinylidene fluoride/polymethyl methacrylate/carbon black membrane after membrane distillation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2022, 138, 104448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik Mansouri, M.; Amidpour, M.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Optimal integration of organic Rankine cycle and desalination systems with industrial processes: Energy-water-environment nexus. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 158, 113740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Yang, H.; Qu, F.; Yu, H.; Liang, H.; Li, G.; Ma, J. Reverse osmosis brine treatment using direct contact membrane distillation: Effects of feed temperature and velocity. Desalination 2017, 423, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartino, J.A.; Khayet, M.; García-Payo, M.C.; El-Bakouri, H.; Riaza, A. Treatment of reverse osmosis brine by direct contact membrane distillation: Chemical pretreatment approach. Desalination 2017, 420, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mericq, J.P.; Laborie, S.; Cabassud, C. Vacuum membrane distillation of seawater reverse osmosis brines. Water Res. 2010, 44, 5260–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Naidu, G.; Jeong, S.; Vigneswaran, S.; Lee, S.; Wang, R.; Fane, A.G. Experimental comparison of submerged membrane distillation configurations for concentrated brine treatment. Desalination 2017, 420, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.E.; Lalia, B.S.; Hashaikeh, R.; Hilal, N. Enhanced performance of direct contact membrane distillation via selected electrothermal heating of membrane surface. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 610, 118224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, V.R.; Castro, L.M.C.; Amaral, M.C.S. Comparative analysis of direct contact and air–gap membrane distillation techniques for water recovery from gold mining wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 344, 127300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, M.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; An, A.K.; Fang, J.; He, T. Anti-wetting behavior of negatively charged superhydrophobic PVDF membranes in direct contact membrane distillation of emulsified wastewaters. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 535, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Sreedhar, N.; Al-Ketan, O.; Rowshan, R.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K.; Arafat, H. 3D printed spacers based on TPMS architectures for scaling control in membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 581, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, S.R.; Ibrahim, S.S.; Alsarayreh, A.A.; Alanezi, A.A.; Jawad, Z.A.; Alsalhy, Q.F. Influence of prolonged operation of CNM/PAC modified PVDF nanocomposite membranes in desalination via vacuum membrane distillation. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Lee, J.-G.; Fortunato, L.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; An, A.K.; Ghaffour, N.; Lee, S.; Jeong, S. Colloidal silica fouling mechanism in direct-contact membrane distillation. Desalination 2022, 527, 115554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, A.; Leaper, S.; Skuse, C.; Zaragoza, G.; Gryta, M.; Gorgojo, P. Membrane cleaning and pretreatments in membrane distillation––A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 129696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.D.; Roca, L.; Zaragoza, G.; Pérez, M.; Berenguel, M. Improving the performance of solar membrane distillation processes for treating high salinity feeds: A process control approach for cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchrit, R.; Boubakri, A.; Hafiane, A.; Bouguecha, S.A.-T. Direct contact membrane distillation: Capability to treat hyper-saline solution. Desalination 2015, 376, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Kalam, S.; Livingston, J.L.; Minjarez, R.; Lee, J.; Lin, S.; Tong, T. The use of anti-scalants in gypsum scaling mitigation: Comparison with membrane surface modification and efficiency in combined reverse osmosis and membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 643, 120077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elcik, H.; Fortunato, L.; Alpatova, A.; Soukane, S.; Orfi, J.; Ali, E.; AlAnsary, H.; Leiknes, T.; Ghaffour, N. Multi-effect distillation brine treatment by membrane distillation: Effect of antiscalant and antifoaming agents on membrane performance and scaling control. Desalination 2020, 493, 114653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijing, L.D.; Woo, Y.C.; Choi, J.-S.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Shon, H.K. Fouling and its control in membrane distillation—A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 475, 215–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitsov, I.; Eykens, L.; Schepper, W.D.; Sitter, K.D.; Dotremont, C.; Nopens, I. Full-scale direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD) model including membrane compaction effects. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 524, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryta, M. Long-term performance of membrane distillation process. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 265, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatab, M.Z.; Ali, K.; Arafat, H.A.; Hassan Ali, M.I. Similarity analysis of membrane distillation utilizing dimensionless parameters derived from process-governing equations. Desalination 2025, 603, 118637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Chen, X.; Mao, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, S.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, W.; Xin, J.H. Fabrication of monolithic omniphobic PVDF membranes based on particle stacking structure for robust and efficient membrane distillation. Desalination 2024, 580, 117547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Qi, L. Hierarchical janus membranes via interfacial engineering: Dual anti-fouling and anti-wetting for sustainable desulfurization wastewater reclamation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, K.T.; Blankert, B.; Horn, H.; Wagner, M.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Bucs, S.; Fortunato, L. Noninvasive monitoring of fouling in membrane processes by optical coherence tomography: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 692, 122291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Koo, J.; Lee, S. System Dynamics Modeling of Scale Formation in Membrane Distillation Systems for Seawater and RO Brine Treatment. Membranes 2024, 14, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cho, H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S. Application of Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) to Analyze Membrane Fouling under Intermittent Operation. Membranes 2023, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, C.; Thamaraiselvan, C.; Jebur, M.; Qian, X.; Wickramasinghe, R. Advancing produced water treatment: Scaling up EC-MF-MDC technology from lab to pilot scale. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 201, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Pathak, N.B.; Wang, C.; Tran, V.H.; Han, D.-S.; Hong, S.; Phuntsho, S.; Shon, H.K. Fouling of reverse osmosis membrane: Autopsy results from a wastewater treatment facility at central park, Sydney. Desalination 2023, 565, 116848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Kim, M.; Choi, H.; Im, S.; Jang, A. Fouling characteristics and cleaning strategies of reverse osmosis membranes at different stages in a wastewater reclamation process. Chemosphere 2025, 377, 144352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yu, D.; Wang, G.; Yue, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Liang, G.; Wei, Y. Characteristics and formation mechanism of membrane fouling in a full-scale RO wastewater reclamation process: Membrane autopsy and fouling characterization. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 563, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.; Mbaya, R.; Popoola, P.; Gomotsegang, F.; Ibrahim, I.; Onyango, M. Predicting the fouling tendency of thin film composite membranes using fractal analysis and membrane autopsy. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 4397–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.J.; Saleem, H. Chapter 11—Reverse Osmosis System Troubleshooting. In Reverse Osmosis Systems; Zaidi, S.J., Saleem, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 375–406. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Niu, Q.J. Recent advances in novel membranes for improved anti-wettability in membrane distillation: A mini review. Desalination 2024, 571, 117066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awanis Hashim, N.; Liu, F.; Moghareh Abed, M.R.; Li, K. Chemistry in spinning solutions: Surface modification of PVDF membranes during phase inversion. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 415–416, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Ma, Z.; Liao, X.; Kosaraju, P.B.; Irish, J.R.; Sirkar, K.K. Pilot plant studies of novel membranes and devices for direct contact membrane distillation-based desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 323, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.-D.; Duke, M.; Xie, Z.; Gray, S. Performance of asymmetric hollow fibre membranes in membrane distillation under various configurations and vacuum enhancement. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 362, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanu, D.P.R.; Zhao, M.; Han, Z.; Keswani, M. Chapter 1—Fundamentals and Applications of Sonic Technology. In Developments in Surface Contamination and Cleaning: Applications of Cleaning Techniques; Kohli, R., Mittal, K.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hejazi, M.-A.A.; Bamaga, O.A.; Al-Beirutty, M.H.; Gzara, L.; Abulkhair, H. Effect of intermittent operation on performance of a solar-powered membrane distillation system. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 220, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.; Cho, H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Analysis of Polyvinylidene Fluoride Membranes Fabricated for Membrane Distillation. Membranes 2021, 11, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Ju, J.; Woo, Y.; Choi, J.-S.; Lee, S. Fabrication and characterization of moderately hydrophobic membrane with enhanced permeability using a phase-inversion method in membrane distillation. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 183, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, P.; Chiao, Y.-H.; Guan, K.; Gonzales, R.R.; Xu, P.; Mai, Z.; Xu, G.; Hu, M.; Kitagawa, T.; et al. Improvement of anti-wetting and anti-scaling properties in membrane distillation process by a facile fluorine coating method. Desalination 2023, 566, 116936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharqawy, M.H.; Lienhard V, J.H.; Zubair, S.M. Thermophysical properties of seawater: A review of existing correlations and data. Desalination Water Treat. 2010, 16, 354–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukane, S.; Naceur, M.W.; Francis, L.; Alsaadi, A.; Ghaffour, N. Effect of feed flow pattern on the distribution of permeate fluxes in desalination by direct contact membrane distillation. Desalination 2017, 418, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, M.H.; Siddiky, A.Y.; Islam, M.A.; Hossain, A.; Rimon, M.I.H.; Oliullah, M.S.; Khan, J.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, N.; Chowdhury, M.A. Progress and prospects of electrospun nanofibrous membranes for water filtration: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2024, 574, 117285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsinger, D.M.; Swaminathan, J.; Guillen-Burrieza, E.; Arafat, H.A.; Lienhard V, J.H. Scaling and fouling in membrane distillation for desalination applications: A review. Desalination 2015, 356, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, N.P.; Nthunya, L.N.; De Canck, E.; Derese, S.; Verliefde, A.R.; Kuvarega, A.T.; Mamba, B.B.; Mhlanga, S.D.; Dlamini, D.S. Congo red dye removal by direct membrane distillation using PVDF/PTFE membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 211, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Fang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wei, H.; Yu, C.-Y. Application of membrane distillation for purification of radioactive liquid. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 12, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayvani Fard, A.; Rhadfi, T.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M.A.; Khraisheh, M.; Hilal, N. Reducing flux decline and fouling of direct contact membrane distillation by utilizing thermal brine from MSF desalination plant. Desalination 2016, 379, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.; Choi, Y.; Cho, H.; Shin, Y.; Lee, S. Comparison of fouling behaviors of hydrophobic microporous membranes in pressure- and temperature-driven separation processes. Desalination 2018, 428, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eykens, L.; De Sitter, K.; Paulussen, S.; Dubreuil, M.; Dotremont, C.; Pinoy, L.; Van der Bruggen, B. Atmospheric plasma coatings for membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 554, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, W.U.; Khan, A.; Mushtaq, N.; Younas, M.; An, X.; Saddique, M.; Farrukh, S.; Hu, Y.; Rezakazemi, M. Electrospun hierarchical fibrous composite membrane for pomegranate juice concentration using osmotic membrane distillation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ortega, E.; Van der Bruggen, B. Chapter 13—Prospects of nanocomposite membranes for water treatment by electrodriven membrane processes. In Nanocomposite Membranes for Water and Gas Separation; Sadrzadeh, M., Mohammadi, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 321–354. [Google Scholar]

- Phuntsho, S.; Listowski, A.; Shon, H.K.; Le-Clech, P.; Vigneswaran, S. Membrane autopsy of a 10year old hollow fibre membrane from Sydney Olympic Park water reclamation plant. Desalination 2011, 271, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-badawy, T.; Othman, M.H.D.; Norddin, M.N.A.M.; Matsuura, T.; Adam, M.R.; Ismail, A.F.; Tai, Z.S.; Zakria, H.S.; Edalat, A.; Jaafar, J.; et al. Omniphobic braid-reinforced hollow fiber membranes for DCMD of oilfield produced water: The effect of process conditions on membrane performance. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 50, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Abdalla, A.A.; Khaleel, M.A.; Hilal, N.; Khraisheh, M.K. Mechanical properties of water desalination and wastewater treatment membranes. Desalination 2017, 401, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, L.; Ghaffour, N.; Alsaadi, A.S.; Nunes, S.P.; Amy, G.L. Performance evaluation of the DCMD desalination process under bench scale and large scale module operating conditions. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 455, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Hassan Ali, M.I. A numerical study of CaCO3 deposition on the membrane surface of direct contact membrane distillation. Desalination 2024, 576, 117364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Ooi, B.S.; Ahmad, A.L.; Leo, C.P.; Low, S.C. Vacuum membrane distillation for desalination: Scaling phenomena of brackish water at elevated temperature. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 254, 117572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryta, M. Water desalination using membrane distillation with acidic stabilization of scaling layer thickness. Desalination 2015, 365, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, S.; Kargari, A. State-of-the-art surface patterned membranes fabrication and applications: A review of the current status and future directions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 196, 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, S.; Ning, R.; Li, P.; Ji, X.; Xu, Y. Treatment of high-salinity brine containing dissolved organic matters by vacuum membrane distillation: A fouling mitigation approach via microbubble aeration. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.O.; Al-Nomazi, M.A.; Al-Amoudi, A.S. Evaluating suitability of source water for a proposed SWRO plant location. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Xu, S.; Hao, F. Differential adsorption of clay minerals: Implications for organic matter enrichment. Earth Sci. Rev. 2023, 246, 104598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, K.; Rangel, E.; Sant’Anna, A.; Louzada, D.; Barbosa, C.; d Almeida, J.R. Evaluation of the electromechanical behavior of polyvinylidene fluoride used as a component of risers in the offshore oil industry. Oil Gas Sci. Technol. 2018, 73, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecozzi, M.; Pietroletti, M.; Scarpiniti, M.; Acquistucci, R.; Conti, M.E. Monitoring of marine mucilage formation in Italian seas investigated by infrared spectroscopy and independent component analysis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 184, 6025–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayan, M.; Krishnegowda, J.; Abhilash, M.; Keerthiraj, D.N.; Shivanna, S. Comparative Study on the Effects of Surface Area, Conduction Band and Valence Band Positions on the Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO-MxOy Heterostructures. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2019, 11, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Concentration (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| Ca2+ | 725.2 |

| Mg2+ | 2156 |

| Na+ | 18,312 |

| K+ | 915.6 |

| HCO3− | 212.8 |

| SO42− | 4830 |

| Cl− | 36,540 |

| TDS | 65,520 |

| Total hardness (as CaCO3) | 10,654 |

| Total suspended solids | 26.6 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Materials | Polyvinylidene fluoride. |

| Module type | Hollow fiber (outside-in) |

| Flow configuration | Counter current |

| Inner diameter (mm) | 1.2 |

| Outer diameter (mm) | 0.7 |

| Thickness (mm) | 0.25 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 9.05 |

| Elongation ratio (%) | 70 |

| Effective membrane area (m2) | 2.3 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Operation mode | Direct contact MD |

| Feed temperature | 55~60 °C |

| Feed flow rate | 60 L/min |

| Product water flow rate | 40 L/min |

| Feed tank volume | 0.1 m3 |

| Nominal capacity | 0.1 m3/day |

| Fiber Position | Contact Angle (MPa) |

|---|---|

| Intact membrane fiber | 104.65 |

| Inner and near-inlet fiber | 47.05 |

| Outer and near-inlet fiber | 59.24 |

| Inner and near-outlet fiber | 41.26 |

| Outer and near-outlet fiber | 53.73 |

| Fiber Position | LEP (Bar) |

|---|---|

| Intact membrane fiber | 2.78 ± 0.67 |

| Inner and near-inlet fiber | 1.21 ± 0.86 |

| Outer and near-inlet fiber | 1.70 ± 0.85 |

| Inner and near-outlet fiber | 1.18 ± 0.40 |

| Outer and near-outlet fiber | 1.76 ± 0.06 |

| Fiber Position | Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|

| Intact membrane fiber | 9.05 |

| Inner and near-inlet fiber | 5.93 |

| Outer and near-inlet fiber | 6.36 |

| Inner and near-outlet fiber | 6.53 |

| Outer and near-outlet fiber | 6.49 |

| Position | Na+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | K+ | Cl− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact membrane fiber | - | - | - | - | - |

| Near-inlet fiber (Inner and outer) | 198.2 | 27.7 | 37.3 | 9.0 | 428.4 |

| Near-outlet fiber (Inner and outer) | 254.7 | 27.8 | 35.7 | 11.0 | 501.8 |

| Position | TOC (Measured as mg/L) | TOC (Converted as mg/m2) |

|---|---|---|

| Intact membrane fiber | - | - |

| Near-inlet fiber (Inner and outer) | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 233 ± 8 |

| Near-outlet fiber (Inner and outer) | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 176 ± 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, H.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-H. Analysis of Fouling in Hollow Fiber Membrane Distillation Modules for Desalination Brine Reduction. Membranes 2025, 15, 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120371

Cho H, Lee S, Choi Y, Lee S, Kim S-H. Analysis of Fouling in Hollow Fiber Membrane Distillation Modules for Desalination Brine Reduction. Membranes. 2025; 15(12):371. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120371

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Hyeongrak, Seoyeon Lee, Yongjun Choi, Sangho Lee, and Seung-Hyun Kim. 2025. "Analysis of Fouling in Hollow Fiber Membrane Distillation Modules for Desalination Brine Reduction" Membranes 15, no. 12: 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120371

APA StyleCho, H., Lee, S., Choi, Y., Lee, S., & Kim, S.-H. (2025). Analysis of Fouling in Hollow Fiber Membrane Distillation Modules for Desalination Brine Reduction. Membranes, 15(12), 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120371