1. Introduction

Protein fouling represents one of the most significant challenges in virus filtration as it affects both the filtrate flux and capacity of the virus filter as well as the degree of virus removal [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Several studies have investigated the mechanisms governing protein fouling and flux decline in commercial virus removal filters. Bieberbach et al. [

7] reported that some monoclonal antibodies cause irreversible fouling of the Virosart HC virus filter, likely due to the presence of small aggregates, while others cause a reversible flux decline attributable to reversible oligomer formation. Suh et al. [

8] compared the fouling behavior of seven commercial virus removal filters using bovine serum albumin as a model foulant. The most rapid flux decline was obtained with the highly asymmetric Viresolve

® NFP membrane, with a capacity of less than 100 L/m

2, while the Planova

TM BioEX and 20N membranes show less than a 15% flux decline after a volumetric throughput of more than 250 L/m

2. Analysis of the flux decline data revealed that the behavior of the Viresolve

® NFP and Pegasus™ SV4 membranes was best described by the pore-constriction model, while the Viresolve

® Pro and Virosart

® CPV membranes follow a complete pore-blockage mechanism. These studies demonstrate that the dominant fouling mechanism is closely linked to both membrane morphology and protein characteristics. Peles et al. [

9,

10] further evaluated the effect of transmembrane pressure on IgG fouling in the Viresolve

® Pro membrane, showing that the flux decline was well described by a sequential pore-blockage and cake-filtration model with fouling parameters strongly dependent on pressure.

Several research groups have shown that protein fouling can significantly compromise virus removal. Bolton et al. [

2] reported that the log reduction value (LRV) for the Viresolve

® NFP filter declines by 4-logs after less than 70 L/m

2 filtration of 1 g/L IgG solutions, with the data well described using a simple model in which protein fouling occurs preferentially in the smallest pores, thereby redirecting the flow to the larger, less retentive, pores. In contrast, Stuckey et al. [

11] evaluated virus retention for the Planova

TM 20N virus removal filter and found no correlation with the extent of fouling. Afzal et al. [

1] found a significant decay in virus retention for the Ultipor

® DV20, Pegasus

TM SV4, and Viresolve

® NFP membranes during filtration of 1 g/L IgG solutions, with a smaller decay in virus retention for the Viresolve

® Pro membrane. The data for the two relatively homogeneous virus filters (the Ultipor

® DV20 and Pegasus

TM SV4) appear to collapse to a single curve when plotted as a function of the flux decay, but very different behavior was seen with the highly asymmetric Viresolve

® NFP and Viresolve

® Pro membranes. This highlights that the impact of fouling on virus retention depends strongly on the membrane morphology and the location of particle capture within the membrane.

Although there have been no direct studies of the changes in pore size or porosity due to protein fouling of virus removal filters, some insights into these phenomena have been obtained by evaluating the effects of protein fouling on the location of virus or nanoparticle capture. Leisi et al. [

4] used confocal microscopy to examine the capture location of fluorescently labeled Minute Virus of Mice (MVM) in the presence and absence of IgG. The labeled virus was captured closer to the entrance of the Planova

TM 20N membrane when the virus filtration was performed in the presence of IgG, which was likely due to constriction of the pores due to protein fouling. Interestingly, the opposite behavior was seen with the Pegasus

TM SV4, with the virus penetrating deeper into the filter. Fallahianbijan et al. [

12] examined the capture of gold nanoparticles within the highly asymmetric Viresolve

® Pro and Viresolve

® NFP membranes using scanning electron microscopy. Fouling by IgG caused the gold nanoparticles to be captured further upstream (closer to the entrance) in the Viresolve

® Pro membrane, but protein fouling had no apparent effect on nanoparticle capture in the Viresolve

® NFP membrane. The basis for these differences in behavior are unclear, in part because there have been no direct 3D visualizations of the pore structure or flow characteristics of fouled nanoporous membranes.

Here, we directly investigate for the first time how protein fouling affects the internal pore structure of the Viresolve

® Pro membrane using focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) to obtain nanometer-resolution 3D reconstructions of the pore space. FIB-SEM is one of the few methods that has been shown to provide accurate characterization of the 3D pore space in clean (pristine) membranes [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The Viresolve

® Pro membrane is one of the most widely used virus removal filters in biopharmaceutical manufacturing. In addition, there has been significant prior work on both the virus retention characteristics and 3D pore space for the clean membrane [

1,

9,

10] that have demonstrated virus retention in a relatively thin region near the exit of the highly asymmetric structure that can be readily studied by FIB-SEM. To quantify the effects of protein fouling, the reconstructed pore volumes for the clean and fouled membranes were used to numerically simulate fluid flow and virus transport/retention in these membranes. This provided insights into how changes in the pore space influence membrane permeability and virus capture behavior. Altogether, our work provides new understanding of how fouling alters the membrane pore structure and how these changes ultimately impact filtration performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Membrane Fouling

Experiments were performed with a single-layer asymmetric Viresolve® Pro membrane using human serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) as a model protein. IgG was obtained from Nova Biologics (Oceanside, CA, USA) as a lyophilized powder, dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to the desired concentration, and then filtered through a 0.2 µm first and then a 0.1 µm pore size membrane to remove any aggregates and undissolved protein.

The polyethersulfone Viresolve

® Pro membranes were provided by MilliporeSigma (Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were cut into 25 mm diameter disks and placed in a polypropylene filter holder (43303010; Advantec MFS, Inc., Dublin, CA, USA) providing an effective filtration area of 3.5 cm

2. The total membrane thickness is approximately 140 µm based on SEM cross-sections previously reported for the same membrane [

12]. The shiny side (size-selective skin) of the membrane was placed facing away from the feed. The membranes were flushed with 70 L/m

2 of PBS, and the membrane permeability was evaluated from the buffer flux measured at different pressures. The permeability (reported in units of L m

−2 h

−1 kPa

−1) corresponds to the slope of the linear flux–pressure relationship.

All fouling experiments were performed under constant pressure operation at 210 kPa. Membranes were fouled by challenging with 0.1 or 1 g/L solutions of IgG in PBS until the filtrate flux had declined by a pre-specified target (either 40% or 90%). After fouling, membrane samples were air-dried for 24 h in a Petri dish before analysis by FIB-SEM. SEM images for gold nanoparticle capture in the clean and fouled Viresolve

® Pro membranes were obtained by Fallahianbijan et al. [

12].

2.2. FIB-SEM Tomography

Sections from both fouled and unfouled membranes were cut into 5 × 5 mm squares and placed on SEM stubs with the shiny side facing upward. Prior to imaging, all samples were sputter-coated with a 5 nm iridium layer using the standard iridium protocol for the Leica EM ACE600 sputter coater (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany); this minimized charging effects during imaging. Images were obtained with a dual-beam FEI Helios 660 FIB-SEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in the Materials Characterization Laboratory at Penn State. During tomography, the sample stage was tilted to 52°, with the membrane surface aligned perpendicular to the milling direction.

First, a 100 nm-thick carbon layer was deposited using the electron beam, followed by a 1 µm-thick carbon layer using the ion beam to protect the membrane from subsequent damage. The location for subsequent milling/observation was chosen randomly, with milling performed using an ion beam at 30 kV and 24 pA to expose a clean cross-section of the membrane. Fiducial markers were introduced to facilitate alignment of both the ion and electron beams. SEM images were obtained sequentially, with 7 nm thick slices of the membrane material removed by ion beam milling between each image. This resulted in approximately 150–200 slices per dataset.

The FIB-SEM slices often showed lateral and vertical drift after image acquisition due to small shifts in the stage, sample charging, or beam intensity over time. To correct for this drift, the uniform carbon protective layer, which appears at the top of each slice, was used as a stable reference across the entire stack of images. Initial alignment attempts using standard methods in Avizo software, Version 2024.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), such as least-squares and gravity-based alignment, introduced noticeable distortion of pore structure, as discussed in the

Supplementary Information. To address this, vertical alignment was performed using a custom-written plugin [

19] in ImageJ software, Version 1.54j [

20], with the carbon deposition layer serving as a consistent template across all slices. Once vertical alignment was complete, horizontal drift was manually corrected in Avizo by overlaying adjacent slices and ensuring continuity of pore features across the sample depth. This two-step approach maintained the natural pore orientation, avoided artificial cropping, and protected the full depth of the fouling zone [

21]. The effectiveness of the alignment procedure was qualitatively assessed by comparing the final reconstruction with results obtained using Avizo’s standard alignment methods (

Figure S1), which exhibited compression artifacts that were not present in the ImageJ-based reconstruction.

Following alignment, the image stack was processed in Avizo to enhance contrast prior to segmenting the porous regions from the surrounding solid material. Because the image brightness was highly variable due to protein fouling, an adaptive histogram equalization was applied to improve contrast in darker regions. All reconstructions were then imported into GeoDict® (Math2Market GmbH, Kaiserslautern, Germany), where a segmentation workflow was applied for both the clean and fouled membranes. The structure was split into two zones (upper and lower) and segmented separately. Local contrast enhancement and independent thresholding were applied to each subregion. After segmentation, the two subregions were merged into a single reconstruction using the ‘Attach’ function in GeoDict®.

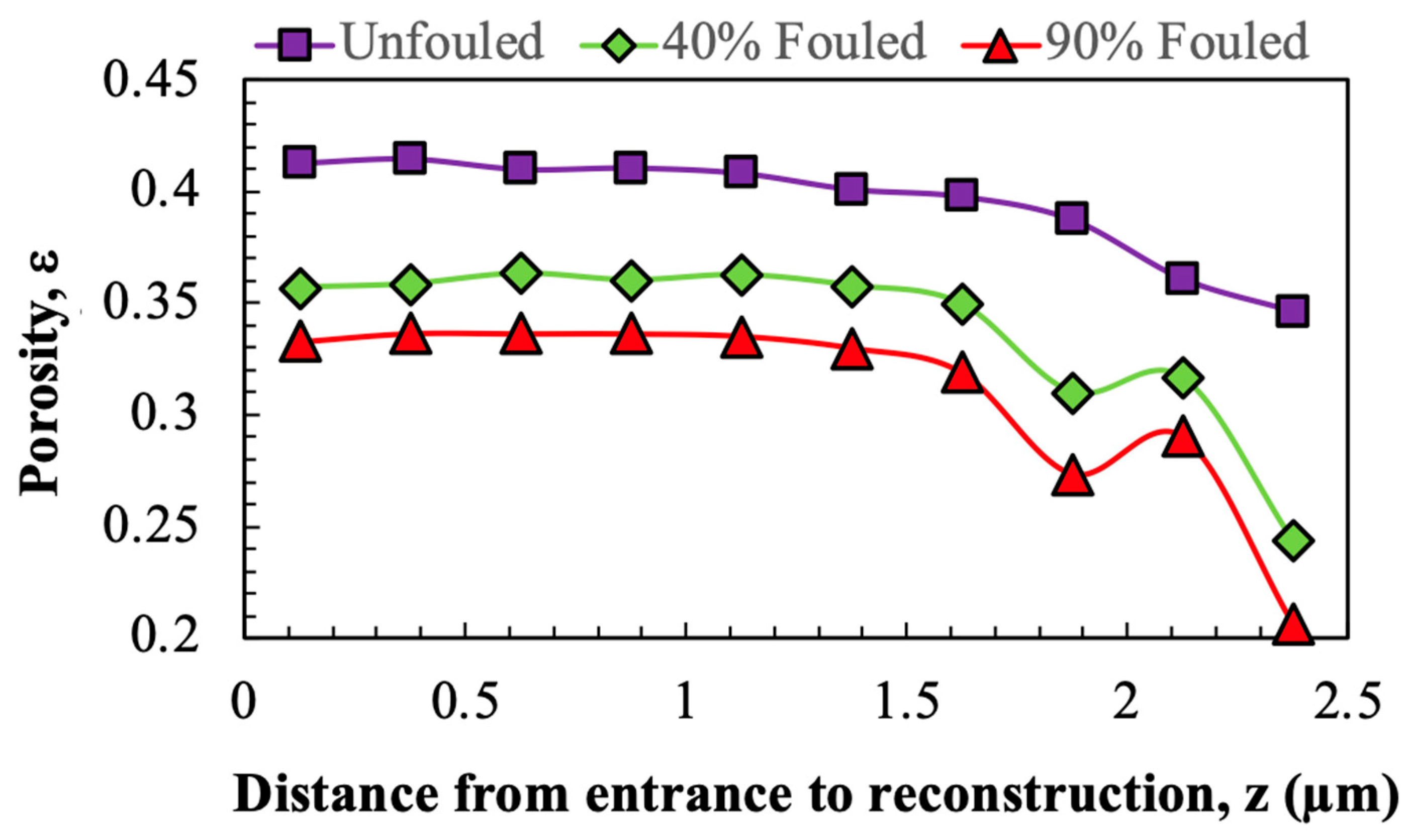

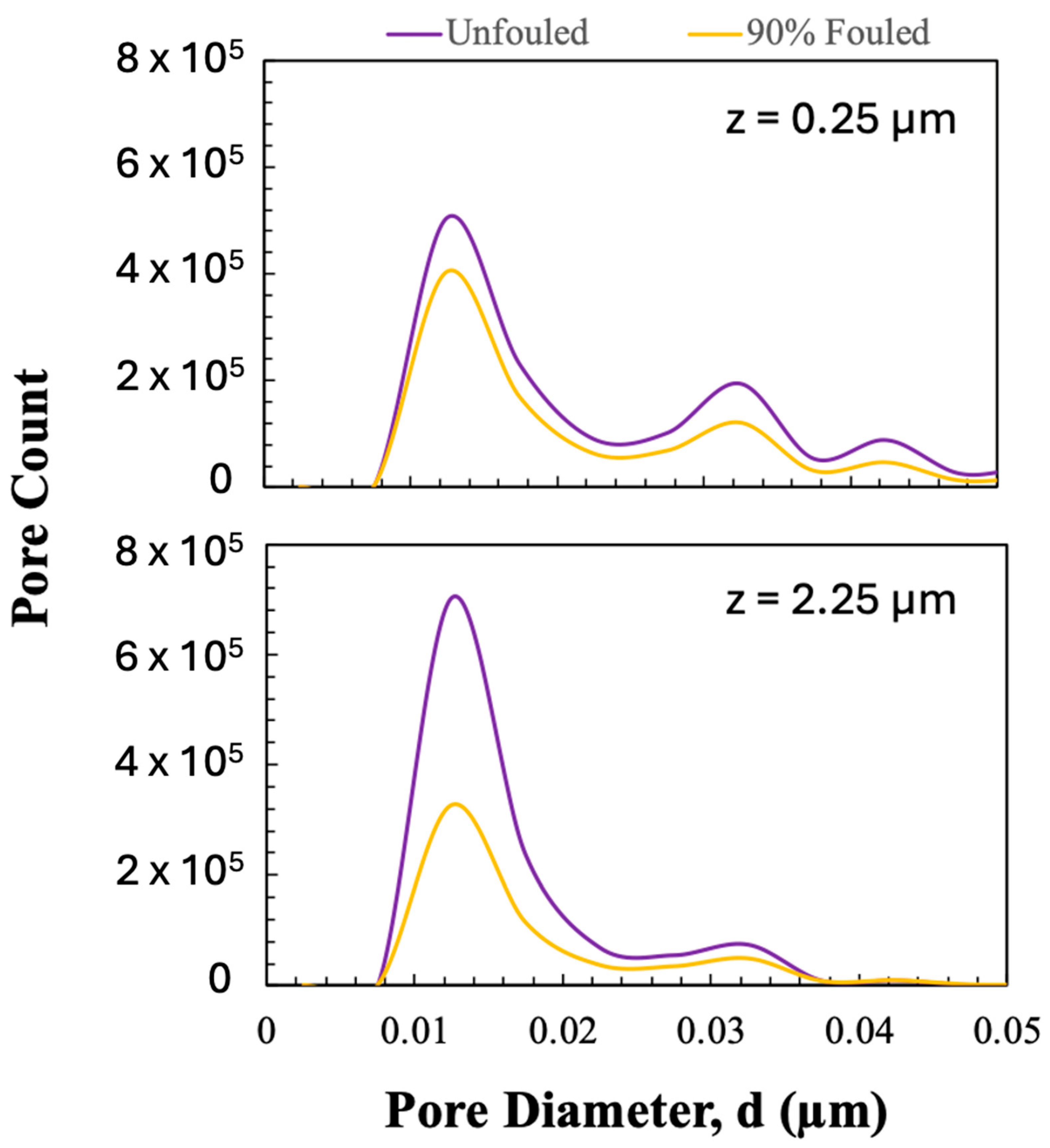

Porosity and pore size distributions were calculated using a custom MATLAB (Version 24.2) script. Porosity was calculated as the number of pore voxels divided by the total number of voxels in any given region of the image. The pore size distribution was evaluated from binary 3D reconstructions (pores = 1, solid = 0) using the ‘bwdist’ function to generate a Euclidean distance map. This map stores, for each pore voxel, the shortest distance to the nearest solid boundary, which represents the radius of the largest sphere that can fit at each point inside the pore space. The pore diameter was calculated by doubling the distance value and multiplying by the voxel size (7 nm).

2.3. Fluid Flow and Particle Transport

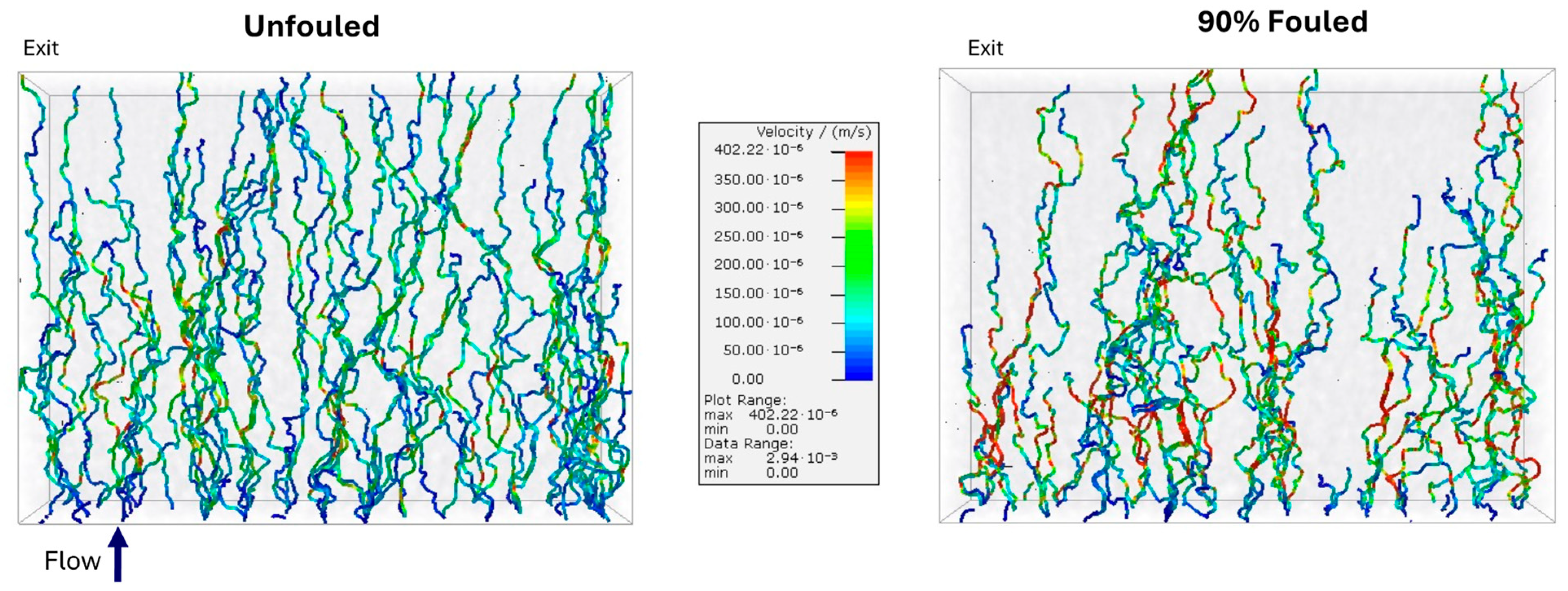

Flow and particle capture simulations were carried out on the segmented 3D volumes using the FlowDict and FilterDict modules in GeoDict®. The flow field was evaluated by solving the steady-state incompressible Stokes flow equations within the segmented domain, with the velocity field updated after each batch of challenge particles. No-slip conditions were imposed at all pore walls, and symmetry boundary conditions were used on the lateral faces. The computational domain corresponded directly to the segmented FIB-SEM volume, with open inlet and outlet boundaries. Since GeoDict® evaluates the velocity field for a fixed inlet pressure and velocity, an iteration was performed on the inlet velocity to match the transmembrane pressure drop of 210 kPa (30 psi) used in the experiments (within a relative error of less than 10−3 corresponding to 0.21 kPa).

Particle transport was evaluated using the FilterDict module, which incorporates both hydrodynamic drag and Brownian motion; electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions were not included in the analysis. The filter was challenged with 20 nm spherical nanoparticles at a concentration of 108 particles/mL. Particle-solid interactions were governed by GeoDict’s built-in Hamaker collision model, with the Hamaker constant set to a negligibly small value (10−200). Particle capture occurred when the particle velocity became negligible (<<1 nm/s) when contacting the pore surface, corresponding to geometric confinement.

The particle challenge was performed in discrete batches of 25 particles. This involved (i) evaluating the steady Stokes flow field through the current pore geometry, (ii) injecting and tracking the motion/capture of 25 particles through that pore geometry, and (iii) updating the pore structure based on the location of captured particles. After each batch, the locations where particles had been captured were mapped onto the voxelized geometry. Voxels in which the particle volume fraction exceeded the default blocking threshold (0.5) were converted from pore space to solid, with the flow field recomputed on this updated structure before challenging with the next particle batch. Thirty batches (750 total particles) were simulated in total, taking 6–10 h of computational time, which provided stable capture statistics while keeping the overall computation time manageable.

4. Conclusions

Our results show for the first time that FIB-SEM tomography can quantify the effects of protein fouling on the 3D pore space and in turn the performance of virus removal filtration membranes. Significant optimization of the FIB-SEM imaging, alignment, and segmentation were required to minimize degradation and desorption of the deposited protein and ensure accurate 3D reconstructions of the pore space. The calculated permeabilities of the clean and fouled membranes were in good agreement with experimental measurements, providing validation of the methodology.

The reconstructed volumes for the unfouled Viresolve® Pro membrane show the expected asymmetric structure, with a thin region having very small pores located right near the exit of the membrane. The fouled membranes show a bright, dense band right near the exit surface, indicating significant protein deposition in this region of the membrane. However, the calculated porosity and pore size distributions also show small but significant changes in the region further upstream, suggesting that IgG fouling occurs throughout a much greater depth of the membrane.

The 3D reconstructions of the pore space were imported into GeoDict

®, enabling calculation of the detailed velocity profiles and the location and extent of nanoparticle capture. The simulations indicate that the clean and fouled membranes both provide very high levels of virus retention (

LRV ≥ 3.57), consistent with independent experimental measurements. Membrane fouling shifted the location of virus capture to a region further upstream of the size-selective skin layer, in good agreement with previous observations of gold nanoparticle capture in clean and fouled Viresolve

® Pro membranes. This shift was due to a significant reduction in the number of small pores near the filter exit, consistent with the preferential blockage of these small pores by the IgG (or IgG dimers or oligomers). This shift in particle capture could potentially alter the overall degree of virus removal and/or the response to process disruptions, which have been previously shown to impact virus retention [

1]. These data provide the first direct measurements of the changes in the 3D pore structure due to protein fouling, providing a general strategy that can be used to obtain important fundamental insights into the effects of protein fouling on the performance of different membranes or membrane processes.