Fouling Mitigation of PVDF Membrane Induced by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)-TiO2 Micelles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Experimental Set-Up

2.2. Membrane Preparation

2.3. Casting Solution Stability

2.4. Membrane Characterization

2.5. Antifouling Performance Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Casting Solution Stability Analysis

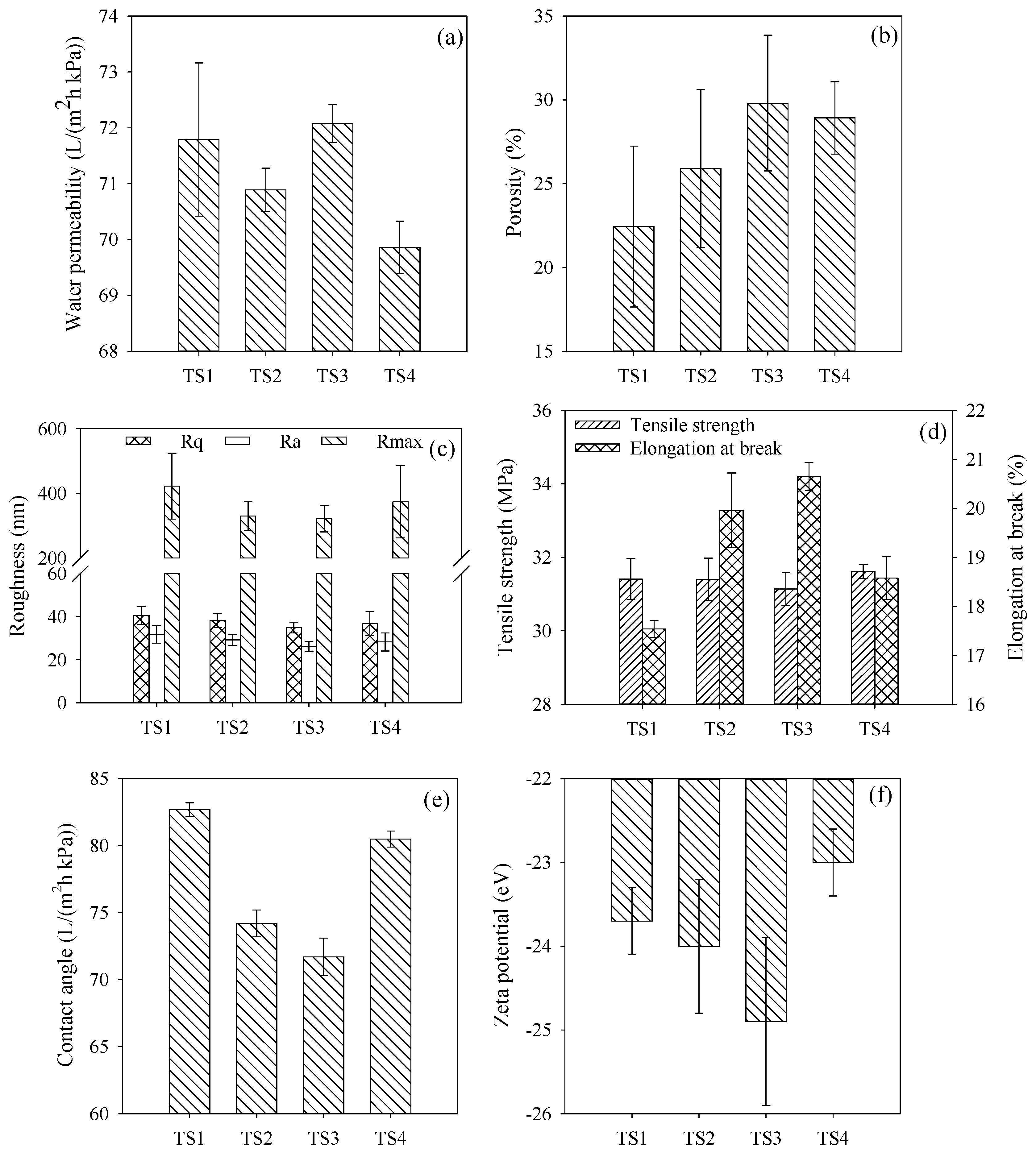

3.2. Membrane Characterizations

3.3. Surface Composition of Membranes

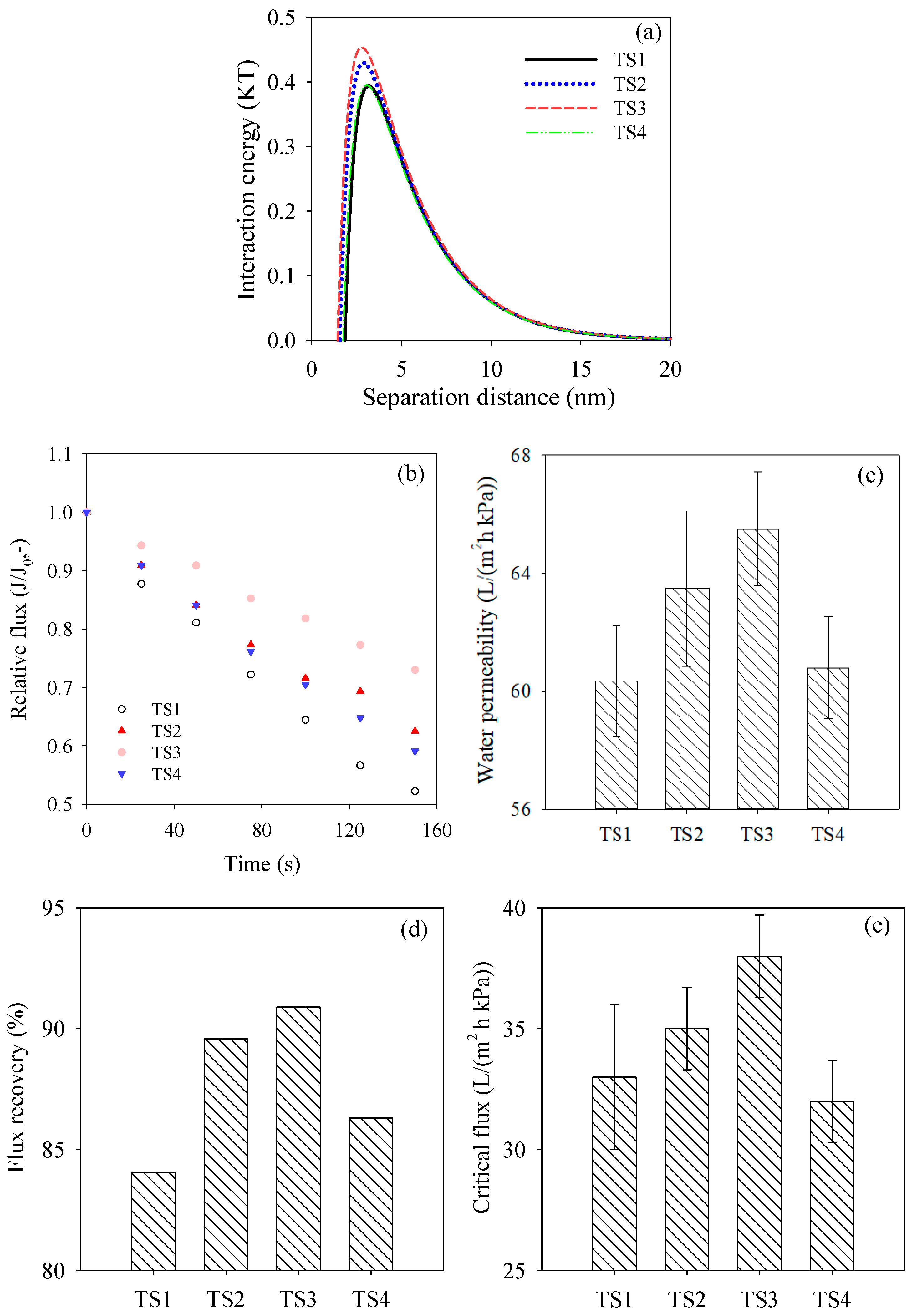

3.4. Membrane Antifouling Performance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, Y.; Gao, H.; Yu, R.; Gao, L.; Zhan, M. Biological-based control strategies for MBR membrane biofouling: A review. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 2597–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, T.; Kim, S.; Jeong, C.; Heo, S.; Yoo, C. Membrane-informed multi-mechanistic predictive maintenance for MBR plants: Early determination of membrane cleaning with biologically driven, physically deposited, and chemically induced fouling model. Desalination 2025, 594, 118263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; He, M.; Su, Y.; Zhao, X.; Elimelech, M.; Jiang, Z. Antifouling membranes for sustainable water purification: Strategies and mechanisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5888–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, L.; Su, C.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Du, E.; Xu, X.; Peng, M. Ferroelectric ultrafiltration membrane with improved antifouling performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S. Comparing the antifouling effects of activated carbon and TiO2 in ultrafiltration membrane development. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 515, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuk, E.; Gungormus, E.; Cihanoğlu, A.; Altinkaya, S.A. Development of a dopamine-based surface modification technique to enhance protein fouling resistance in commercial ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 717, 123554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-S.; Ke, S.-C.; Huang, Y.-X. Simultaneous fouling and scaling-resistant membrane based on glutamic acid grafting for robust membrane distillation. Desalination 2024, 587, 117948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Yan, S.; Li, W.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X. Effect of the surface coating of carbonyl iron particles on the dispersion stability of magnetorheological fluid. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cohen, Y. Fouling resistant and performance tunable ultrafiltration membranes via surface graft polymerization induced by atmospheric pressure air plasma. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 286, 120490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulad, F.; Zinatizadeh, A.A.; Zinadini, S.; Razmjou, A. An efficient approach in water desalination using high flux induced magnetic-field hydroxyl-functionalized MgFe2O4/CA RO membranes with organic/inorganic fouling control capability. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 715, 123437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Wang, Q.-Z.; Wang, Y.-F.; Huo, H.-M.; Kou, F.-Q.; Zhang, S.-B.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, D.; Hao, L.; Chang, Y.-J.; et al. Synergistic manipulation of the polymorphic structure and hydrophilicity of PVDF membranes based on the in-situ esterification reaction to prepare anti-fouling PVDF membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 715, 123474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Chi, L.; Zhou, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z. Fabrication of TiO2-modified polytetrafluoroethylene ultrafiltration membranes via plasma-enhanced surface graft pretreatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 360, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Su, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Z. Fabrication of antifouling polymer–inorganic hybrid membranes through the synergy of biomimetic mineralization and nonsolvent induced phase separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 7287–7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jian, Z.; Jiang, M.; Peng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, J. Influence of Dispersed TiO2 Nanoparticles via Steric Interaction on the Antifouling Performance of PVDF/TiO2 Composite Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, E.; Elimelech, M.; Hong, S. Membrane characterization by dynamic hysteresis: Measurements, mechanisms, and implications for membrane fouling. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 366, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, C.; Wu, Z. Modification of poly (vinylidene fluoride)/polyethersulfone blend membrane with polyvinyl alcohol for improving antifouling ability. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 466, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painuly, R.; Anand, V. Examining the Interplay of Hydrolysed Polyacrylamide and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate on Emulsion Stability: Insights from Turbiscan and Electrocoalescence Studies. Langmuir 2024, 40, 17710–17721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekoue Nguela, J.; Pereira, Y.F.; Sieczkowski, N.; Vernhet, A. Application of Turbiscan Lab® to study the mechanism of fining in red wine using a specific yeast protein extract: A comparison with gelatine. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 699, 134649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmizadeh, A.; Goli, S.A.H.; Mohammadifar, M.A.; Rahimmalek, M. Fabrication and characterization of pectin-zein nanoparticles containing tanshinone using anti-solvent precipitation method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129463. [Google Scholar]

- Atanase, L.I.; Lerch, J.-P.; Riess, G. Water dispersibility of non-aqueous emulsions stabilized and viscosified by a poly(butadiene)-poly(2-vinylpyridine)-poly(ethylene oxide) (PBut-P2VP-PEO) triblock copolymer. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2015, 464, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewska, M.; Szewczuk-Karpisz, K. Removal possibilities of colloidal chromium (III) oxide from water using polyacrylic acid. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 3657–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Z. Enhanced antifouling behaviours of polyvinylidene fluoride membrane modified through blending with nano-TiO2/polyethylene glycol mixture. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 345, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Pan, C.; Wu, Z. Comparison of antifouling behaviours of modified PVDF membranes by TiO2 sols with different nanoparticle size: Implications of casting solution stability. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 525, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzaskus, K.W.; Lee, S.L.; de Vos, W.M.; Kemperman, A.; Nijmeijer, K. Fouling behavior of silica nanoparticle-surfactant mixtures during constant flux dead-end ultrafiltration. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 506, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozia, S.; Czyżewski, A.; Sienkiewicz, P.; Darowna, D.; Szymański, K.; Zgrzebnicki, M. Influence of sodium dodecyl sulfate on the morphology and performance of titanate nanotubes/polyethersulfone mixed-matrix membranes. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 208, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi, N.; Madaeni, S.S.; Alizadeh, A.; Daraei, P.; Vatanpour, V.; Falsafi, M. Fabrication of cellulose acetate/sodium dodecyl sulfate nanofiltration membrane: Characterization and performance in rejection of pesticides. Desalination 2012, 290, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Shi, S.; Cao, H.; Shan, B.; Sheng, Y. Property characterization and mechanism analysis on organic fouling of structurally different anion exchange membranes in electrodialysis. Desalination 2018, 428, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Song, L. Influence of sodium dodecyl sulfate on colloidal fouling potential during ultrafiltration. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2006, 281, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshmann, N.; Nghiem, L.D.; Schafer, A.I. Fouling mechanisms of submerged ultrafiltration membranes in greywater recycling. Desalination 2005, 179, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childress, A.E.; Elimelech, M. Relating Nanofiltration Membrane Performance to Membrane Charge (Electrokinetic) Characteristics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 3710–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, E.M.V.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Elimelech, M. Effect of membrane surface roughness on colloid-membrane DLVO interactions. Langmuir 2003, 19, 4836–4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.-Y.; Xiong, S.-W.; Zhang, P.; Fu, P.-G.; Gai, J.-G. Nanoscale polyelectrolyte/metal ion hydrogel modified RO membrane with dual anti-fouling mechanism and superhigh transport property. Desalination 2020, 488, 114510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Garcia, V.; Ruano, M.V.; Alliet, M.; Brepols, C.; Comas, J.; Harmand, J.; Heran, M.; Mannina, G.; Rodriguez-Roda, I.; Smets, I.; et al. Modeling MBR fouling: A critical review analysis towards establishing a framework for good modeling practices. Water Res. 2025, 268, 122611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Membranes | PVDF | DMSO | DMAc | PEG | TiO2 | SDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS1 | 8 | 43 | 43 | 6 | 0.15 | 0 |

| TS2 | 8 | 43 | 43 | 6 | 0.15 | 0.075 |

| TS3 | 8 | 43 | 43 | 6 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| TS4 | 8 | 43 | 43 | 6 | 0.15 | 0.3 |

| Surface Tension Parameters for Each Membrane (mJ/m2) | |||||||

| Sample No. | γLW | γ+ | γ− | γAB | γTOT | ||

| TS1 | 33.42 ± 0.21 | 0.52 ± 0.10 | 4.24 ± 0.55 | 2.96 ± 0.10 | 36.38 ± 0.29 | ||

| TS2 | 31.78 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 12.19 ± 0.97 | 3.28 ± 0.13 | 35.06 ± 0.13 | ||

| TS3 | 33.56 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 14.23 ± 1.75 | 1.81 ± 0.39 | 35.38 ± 0.43 | ||

| TS4 | 33.91 ± 0.18 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 7.53 ± 0.77 | 1.50 ± 0.35 | 35.40 ± 0.17 | ||

| BSA | 35.14 ± 1.13 | 0.28 ± 0.14 | 17.01 ± 1.87 | 3.81 ± 2.06 | 38.95 ± 1.41 | ||

| The Free Energy of Cohesion of Membranes (mJ/m2) | The Free Energy of Adhesion of Membranes (mJ/m2) | ||||||

| Membrane No. | ΔG121LW | Δ121GAB | ΔG121SWS | ΔG123LW | ΔG123AB | ΔG123SWS | |

| TS1 | −2.47 ± 0.08 | −51.78 ± 1.49 | −54.26 ± 1.53 | −2.80 ± 0.05 | −35.20 ± 1.07 | −38.00 ± 1.09 | |

| TS2 | −1.87 ± 0.01 | −28.57 ± 2.42 | −30.45 ± 2.43 | −2.44 ± 0.01 | −22.68 ± 1.22 | −25.12 ± 1.23 | |

| TS3 | −2.89 ± 0.03 | −22.37 ± 4.13 | −25.26 ± 4.16 | −3.03 ± 0.01 | −19.49 ± 1.92 | −22.51 ± 1.94 | |

| TS4 | −2.66 ± 0.07 | −44.06 ± 1.98 | −46.73 ± 1.91 | −2.91 ± 0.04 | −29.83 ± 1.12 | −32.74 ± 1.08 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Bo, S.; Wang, C.; Jian, Z.; Chu, Y.; Qiu, S.; Chen, H.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, X.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Fouling Mitigation of PVDF Membrane Induced by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)-TiO2 Micelles. Membranes 2025, 15, 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110330

Zhang J, Bo S, Wang C, Jian Z, Chu Y, Qiu S, Chen H, Xiong Q, Yang X, Xiao Z, et al. Fouling Mitigation of PVDF Membrane Induced by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)-TiO2 Micelles. Membranes. 2025; 15(11):330. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110330

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jie, Shiying Bo, Chunhua Wang, Zicong Jian, Yuehuan Chu, Si Qiu, Hongyan Chen, Qiancheng Xiong, Xiaofang Yang, Zicheng Xiao, and et al. 2025. "Fouling Mitigation of PVDF Membrane Induced by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)-TiO2 Micelles" Membranes 15, no. 11: 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110330

APA StyleZhang, J., Bo, S., Wang, C., Jian, Z., Chu, Y., Qiu, S., Chen, H., Xiong, Q., Yang, X., Xiao, Z., & Liu, G. (2025). Fouling Mitigation of PVDF Membrane Induced by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)-TiO2 Micelles. Membranes, 15(11), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110330