Revisiting Whooping Cough: Global Drivers and Implications of Pertussis Resurgence in the Acellular Vaccine Era

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Clinical Presentation and Host Immunity

4. The Primary Drivers of Resurgence

4.1. Driver 1: Waning and Imperfect Acellular Vaccine Immunity

4.2. Driver 2: Vaccine-Driven Pathogen Evolution

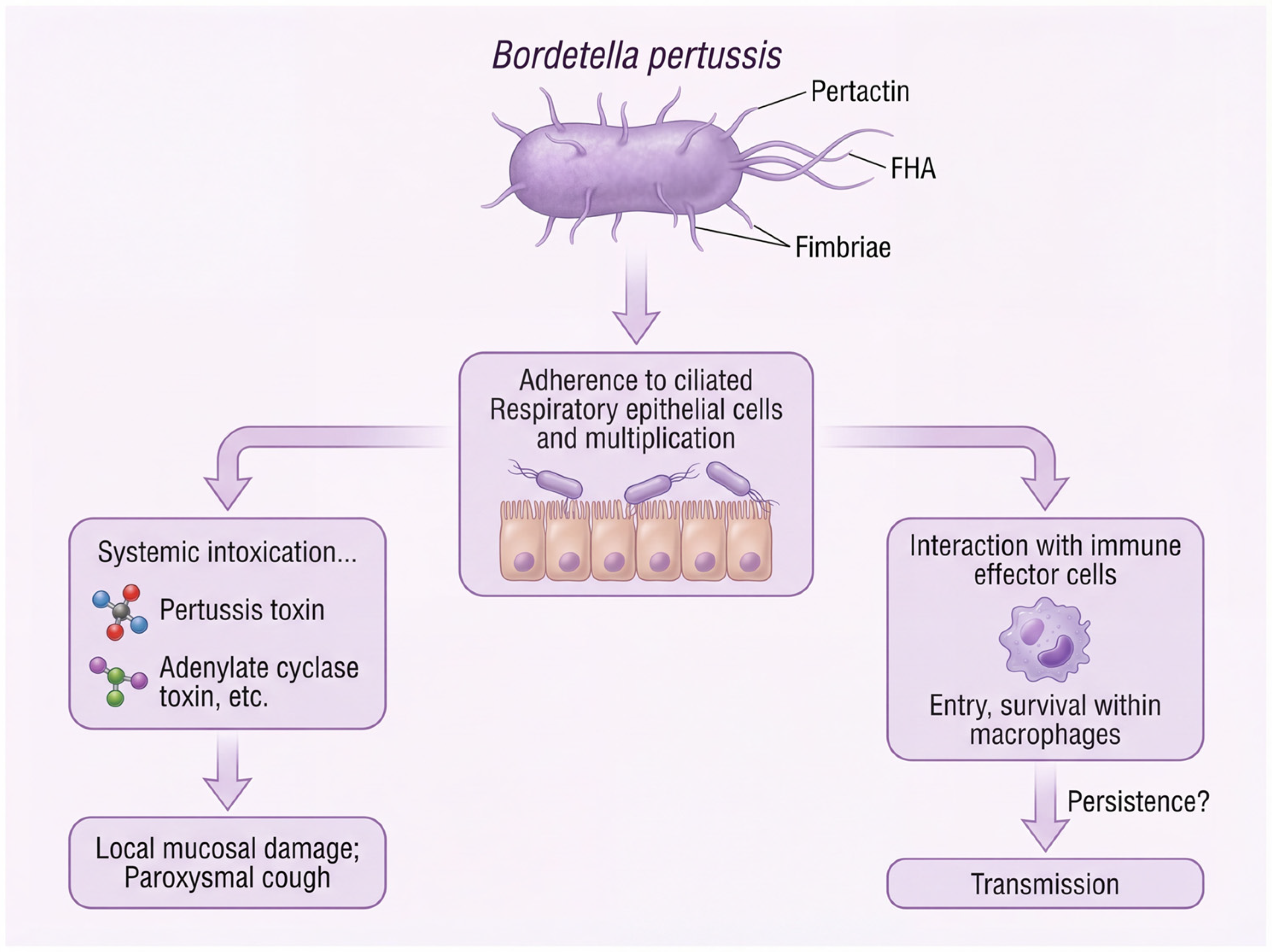

| Virulence Factor [Reference] | Structure & Location | Role in Pathogenesis | Included in aP Vaccines? | Evolution & Vaccine Evasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxins | ||||

| Pertussis Toxin (PT) [31] | Secreted AB5-type exotoxin | Ribosylates inhibitory G proteins, disrupting cellular signaling and causing systemic symptoms (e.g., lymphocytosis). | Yes (All formulations) | ptxP3 lineage: Promoter mutation increases PT production, potentially enhancing transmission fitness and immune suppression [27,28] |

| Adenylate Cyclase Toxin (ACT) [32] | RTX toxin (Extracytoplasmic) | Converts intracellular ATP to cAMP, disabling immune effector cells (phagocytes). | No | Not under direct vaccine pressure, but its role in neutralizing innate immunity remains critical for colonization. |

| Tracheal Cytotoxin (TCT) [33] | Peptidoglycan fragment (Extracellular) | Damages ciliated respiratory cells, inhibiting mucociliary clearance. | No | Evolution not documented; its effect is synergistic with other toxins. |

| Dermonecrotic Toxin (DNT) [34] | Heat-labile A-B toxin (Cytoplasm) | Activates Rho GTPase, causing vasoconstriction and cell death. | No | Not a target of vaccine-induced immunity. |

| Lipo-oligosaccharide (LOS) [35] | Endotoxin (Surface) | Triggers pro-inflammatory responses; contributes to coughing. | No | Not a target of vaccine-induced immunity. |

| Adhesins | ||||

| Pertactin (PRN) [24,29] | Autotransporter protein (Surface) | Mediates binding to host cells; confers resistance to neutrophil-mediated clearance. | Yes (3- & 5-component) | Pertactin-deficiency (PRN-): Widespread global emergence via IS481 insertions, point mutations, and deletions, allowing evasion of PRN-specific antibodies [36]. |

| Fimbriae (FIM2/3) [30,37] | Filamentous proteins (Surface) | Facilitate attachment to tracheal epithelial cells; serotype-specific immunity. | Yes (FIM2/3 in multi-component) | Antigenic Divergence: Amino acid changes in FIM2 and FIM3 proteins reduce antibody recognition, widening the antigenic gap [38,39]. |

| Filamentous Hemagglutinin (FHA) [40] | Filamentous protein (Cell wall) | Key adhesin; binds to ciliated epithelium and immune cell receptors. | Yes (Most formulations) | Antigenic variation is less common than for PRN or FIM, but its role in attachment remains vital. |

| Other systems | ||||

| Type III Secretion System (T3SS) [41,42] | Needle-like injectisome (Cell envelope) | Injects effector proteins directly into host cells. | No | A potential target for next-generation vaccines, as it is essential for virulence and conserved. |

4.3. Driver 3: The Emergence of Antimicrobial Resistance

5. Genomic Epidemiology and Global Surveillance

5.1. Geographic Distribution of Lineages

5.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing as a Surveillance Tool

6. Emergence of Antimicrobial Resistance

6.1. Mechanisms of Macrolide Resistance

6.2. Molecular Epidemiology and Global Spread

6.3. Implications for Treatment and Public Health

7. Epidemiological Consequences and Public Health Implications

- −

- Diagnosis: Increased clinical suspicion and PCR testing are needed for adolescents and adults presenting with prolonged cough.

- −

- Treatment: In regions with potential importation of resistant strains, antibiotic susceptibility testing should be considered.

- −

- Vaccination: Standard infant schedules are insufficient. Adolescent and adult booster doses, maternal immunization during pregnancy, and “cocooning” of newborns are essential to limit transmission.

- −

- Surveillance: The non-negotiable need for WGS-integrated surveillance to track lineage replacement and antigenic variation in real-time.

8. Challenges and Future Directions

8.1. Data and Surveillance Gaps

8.2. Vaccine Implications

8.3. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aP | acellular pertussis vaccine; |

| wP | whole-cell pertussis vaccine; |

| WGS | whole-genome sequencing; |

| PT | pertussis toxin; |

| FHA | filamentous hemagglutinin; |

| Prn | pertactin; |

| Fim | fimbriae; |

| Tdap | tetanus–diphtheria–acellular pertussis vaccine; |

| MLVA | multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis; |

| PFGE | pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; |

| SNP | single-nucleotide polymorphism; |

| AMR | antimicrobial resistance; |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration; |

| TMP-SMX | trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; |

| Th1/Th2/Th17 | T helper 1/2/17; |

| IFN-γ | interferon-gamma; |

| IL | interleukin; |

| IgA/IgG | immunoglobulin A/G; |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction; |

| LMICs | low- and middle-income countries; |

| OMV | outer membrane vesicle. |

References

- Lauria, A.M.; Zabbo, C.P. Pertussis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso, N.; Koenig, C. Pertussis Vaccination: The Challenges Ahead. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 46, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, P.; Merkel, T.J. Pertussis vaccines and protective immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2019, 59, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Pertussis epidemic—Washington, 2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2012, 61, 517–522. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, C.L.; Gonyar, L.A.; Zacca, F.; Sisti, F.; Fernandez, J.; Wong, T.; Damron, F.H.; Hewlett, E.L. Bordetella pertussis Can Be Motile and Express Flagellum-Like Structures. mBio 2019, 10, e00787-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Y.F.; Manivannan, K.; Fernandez, R.C. Bordetella pertussis. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 1192–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, J.; Malcova, I.; Sinkovec, L.; Holubova, J.; Streparola, G.; Jurnecka, D.; Kucera, J.; Sedlacek, R.; Sebo, P.; Kamanova, J. Cytotoxicity of the effector protein BteA was attenuated in Bordetella pertussis by insertion of an alanine residue. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littler, D.R.; Ang, S.Y.; Moriel, D.G.; Kocan, M.; Kleifeld, O.; Johnson, M.D.; Tran, M.T.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; Summers, R.J.; et al. Structure-function analyses of a pertussis-like toxin from pathogenic Escherichia coli reveal a distinct mechanism of inhibition of trimeric G-proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 15143–15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaslow, H.R.; Burns, D.L. Pertussis toxin and target eukaryotic cells: Binding, entry, and activation. FASEB J. 1992, 6, 2684–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashok, Y.; Miettinen, M.; Oliveira, D.K.H.; Tamirat, M.Z.; Näreoja, K.; Tiwari, A.; Hottiger, M.O.; Johnson, M.S.; Lehtiö, L.; Pulliainen, A.T. Discovery of Compounds Inhibiting the ADP-Ribosyltransferase Activity of Pertussis Toxin. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, K.M.; Chen, L.; Carbonetti, N.H. Pertussis Toxin Promotes Pulmonary Hypertension in an Infant Mouse Model of Bordetella pertussis Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, P.; Wang, Y.; Gregg, K.; Zimmerman, L.; Molano, D.; Maldonado Villeda, J.; Sebo, P.; Merkel, T.J. A whole-cell pertussis vaccine engineered to elicit reduced reactogenicity protects baboons against pertussis challenge. mSphere 2024, 9, e0064724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saso, A.; Kampmann, B.; Roetynck, S. Vaccine-Induced Cellular Immunity against Bordetella pertussis: Harnessing Lessons from Animal and Human Studies to Improve Design and Testing of Novel Pertussis Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solans, L.; Debrie, A.S.; Borkner, L.; Aguiló, N.; Thiriard, A.; Coutte, L.; Uranga, S.; Trottein, F.; Martín, C.; Mills, K.H.G.; et al. IL-17-dependent SIgA-mediated protection against nasal Bordetella pertussis infection by live attenuated BPZE1 vaccine. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 1753–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbers, G.; van Gageldonk, P.; Kassteele, J.V.; Wiedermann, U.; Desombere, I.; Dalby, T.; Toubiana, J.; Tsiodras, S.; Ferencz, I.P.; Mullan, K.; et al. Circulation of pertussis and poor protection against diphtheria among middle-aged adults in 18 European countries. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, K.; Glazer, S. The potential role of subclinical Bordetella Pertussis colonization in the etiology of multiple sclerosis. Immunobiology 2016, 221, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.R.; Sette, A.; da Silva Antunes, R. Adaptive immune response to Bordetella pertussis during vaccination and infection: Emerging perspectives and unanswered questions. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2024, 23, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locht, C.; Rubin, K. The potential public health benefit of live-attenuated pertussis vaccines. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2025, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdin, N.; Handy, L.K.; Plotkin, S.A. What Is Wrong with Pertussis Vaccine Immunity? The Problem of Waning Effectiveness of Pertussis Vaccines. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a029454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K.; Righolt, C.H.; Elliott, L.J.; Fanella, S.; Mahmud, S.M. Pertussis vaccine effectiveness and duration of protection—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3120–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N.P.; Bartlett, J.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A.; Fireman, B.; Baxter, R. Waning protection after fifth dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Zambrano, J.C.; Abrudan, S.; Macina, D. Understanding the Epidemiology and Contributing Factors of Post-COVID-19 Pertussis Outbreaks: A Narrative Review. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damron, F.H.; Barbier, M.; Dubey, P.; Edwards, K.M.; Gu, X.X.; Klein, N.P.; Lu, K.; Mills, K.H.G.; Pasetti, M.F.; Read, R.C.; et al. Overcoming Waning Immunity in Pertussis Vaccines: Workshop of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Caulfield, A.; Dewan, K.K.; Harvill, E.T. Pertactin-Deficient Bordetella pertussis, Vaccine-Driven Evolution, and Reemergence of Pertussis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gouw, D.; Hermans, P.W.; Bootsma, H.J.; Zomer, A.; Heuvelman, K.; Diavatopoulos, D.A.; Mooi, F.R. Differentially expressed genes in Bordetella pertussis strains belonging to a lineage which recently spread globally. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorji, D.; Mooi, F.; Yantorno, O.; Deora, R.; Graham, R.M.; Mukkur, T.K. Bordetella pertussis virulence factors in the continuing evolution of whooping cough vaccines for improved performance. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 207, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Octavia, S.; Bahrame, Z.; Sintchenko, V.; Gilbert, G.L.; Lan, R. Selection and emergence of pertussis toxin promoter ptxP3 allele in the evolution of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012, 12, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luan, Y.; Du, Q.; Shu, C.; Peng, X.; Wei, H.; Hou, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. The global prevalence ptxP3 lineage of Bordetella pertussis was rare in young children with the co-purified aPV vaccination: A 5 years retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heininger, U.; Martini, H.; Eeuwijk, J.; Prokić, I.; Guignard, A.P.; Turriani, E.; Duchenne, M.; Berlaimont, V. Pertactin deficiency of Bordetella pertussis: Insights into epidemiology, and perspectives on surveillance and public health impact. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2435134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, K.; Skerry, C.; Carbonetti, N. Association of Pertussis Toxin with Severe Pertussis Disease. Toxins 2019, 11, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregg, K.A.; Merkel, T.J. Pertussis Toxin: A Key Component in Pertussis Vaccines? Toxins 2019, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonetti, N.H. Pertussis toxin and adenylate cyclase toxin: Key virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis and cell biology tools. Future Microbiol. 2010, 5, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessie, D.K.; Lodes, N.; Oberwinkler, H.; Goldman, W.E.; Walles, T.; Steinke, M.; Gross, R. Activity of Tracheal Cytotoxin of Bordetella pertussis in a Human Tracheobronchial 3D Tissue Model. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 614994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruya, S.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Fukui-Miyazaki, A.; Tsukamoto, K.; Shinoda, N.; Motooka, D.; Nakamura, S.; Ishigaki, K.; Shinzawa, N.; et al. Bordetella Dermonecrotic Toxin Is a Neurotropic Virulence Factor That Uses Ca(V)3.1 as the Cell Surface Receptor. mBio 2020, 11, e03146-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Huang, L.; Luo, S.; Qiao, R.; Liu, F.; Li, X. A novel vaccine formulation candidate based on lipooligosaccharides and pertussis toxin against Bordetella pertussis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1124695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawloski, L.C.; Queenan, A.M.; Cassiday, P.K.; Lynch, A.S.; Harrison, M.J.; Shang, W.; Williams, M.M.; Bowden, K.E.; Burgos-Rivera, B.; Qin, X.; et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of pertactin-deficient Bordetella pertussis in the United States. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2014, 21, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, M.J.; Harris, S.R.; Advani, A.; Arakawa, Y.; Bottero, D.; Bouchez, V.; Cassiday, P.K.; Chiang, C.S.; Dalby, T.; Fry, N.K.; et al. Global population structure and evolution of Bordetella pertussis and their relationship with vaccination. mBio 2014, 5, e01074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, R.M.; Rooke, J.L.; Wells, T.J.; Cunningham, A.F.; Henderson, I.R. Type 5 secretion system antigens as vaccines against Gram-negative bacterial infections. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gent, M.; Bart, M.J.; van der Heide, H.G.; Heuvelman, K.J.; Mooi, F.R. Small mutations in Bordetella pertussis are associated with selective sweeps. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clantin, B.; Hodak, H.; Willery, E.; Locht, C.; Jacob-Dubuisson, F.; Villeret, V. The crystal structure of filamentous hemagglutinin secretion domain and its implications for the two-partner secretion pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6194–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarino Romero, R.; Bibova, I.; Cerny, O.; Vecerek, B.; Wald, T.; Benada, O.; Zavadilova, J.; Osicka, R.; Sebo, P. The Bordetella pertussis type III secretion system tip complex protein Bsp22 is not a protective antigen and fails to elicit serum antibody responses during infection of humans and mice. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 2761–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, K.M.; First, N.; Kamanova, J.; Williams, T.L.; Johnson, S.; King, J.; Scanlon, K.M.; Azouz, N.P.; Mattoo, S.; Skerry, C.; et al. The Bordetella type III secretion system effector BteA targets host eosinophil-epithelial signaling to promote IL-1Ra expression and persistence. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chiu, C.H.; Heininger, U.; Hozbor, D.F.; Tan, T.Q.; von König, C.W. Emerging macrolide resistance in Bordetella pertussis in mainland China: Findings and warning from the global pertussis initiative. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 8, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Bouchez, V.; Soares, A.; Trombert-Paolantoni, S.; Aït El Belghiti, F.; Cohen, J.F.; Armatys, N.; Landier, A.; Blanchot, T.; Hervo, M.; et al. Resurgence of Bordetella pertussis, including one macrolide-resistant isolate, France, 2024. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, Q.; Wen, J.; Luo, Y.; Guo, J.; Qin, Y.; Lai, W.; Deng, W.; Ji, C.; Mai, R.; Zheng, M.; et al. Molecular epidemiology and increasing macrolide resistance of Bordetella pertussis isolates in Guangzhou, China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaska, L.; Barkoff, A.M.; Mertsola, J.; He, Q. Macrolide Resistance in Bordetella pertussis: Current Situation and Future Challenges. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Greeff, S.C.; de Melker, H.E.; van Gageldonk, P.G.; Schellekens, J.F.; van der Klis, F.R.; Mollema, L.; Mooi, F.R.; Berbers, G.A. Seroprevalence of pertussis in The Netherlands: Evidence for increased circulation of Bordetella pertussis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, T.Y.; Luk, H.K.; Choi, G.K.; Chau, S.K.; Tsang, L.M.; Tse, C.W.; Fung, K.K.; Lam, J.Y.; Ng, H.L.; Tang, T.H.; et al. Macrolide-Resistant Bordetella pertussis in Hong Kong: Evidence for Post-COVID-19 Emergence of ptxP3-Lineage MT28 Clone from a Hospital-Based Surveillance Study. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Yan, G.; Li, Y.; Xie, L.; Ke, Y.; Qiu, S.; Wu, S.; Shi, X.; Qin, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Pertussis upsurge, age shift and vaccine escape post-COVID-19 caused by ptxP3 macrolide-resistant Bordetella pertussis MT28 clone in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, K.; Yao, S.; Chiang, C.S.; Thuy, P.T.B.; Nga, D.T.T.; Huong, D.T.; Dien, T.M.; Vichit, O.; Vutthikol, Y.; Sovannara, S.; et al. Genotyping and macrolide-resistant mutation of Bordetella pertussis in East and South-East Asia. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 31, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Zhou, J.; Meng, J.; Liu, Z.; Nijiati, Y.; He, L.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, A.; Yan, G.; et al. Emergence and spread of MT28 ptxP3 allele macrolide-resistant Bordetella pertussis from 2021 to 2022 in China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 128, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Du, Q.; Shi, W.; Meng, Q.; Yuan, L.; Hu, H.; Ma, L.; Li, D.; Yao, K. Sharp rise in high-virulence Bordetella pertussis with macrolides resistance in Northern China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2475841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q.; Luo, J.; Yuan, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Zeng, M. Domination of an emerging erythromycin-resistant ptxP3 Bordetella pertussis clone in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2023, 62, 106835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matczak, S.; Bouchez, V.; Leroux, P.; Douché, T.; Collinet, N.; Landier, A.; Gianetto, Q.G.; Guillot, S.; Chamot-Rooke, J.; Hasan, M.; et al. Biological differences between FIM2 and FIM3 fimbriae of Bordetella pertussis: Not just the serotype. Microbes Infect. 2023, 25, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, N.; Han, H.J.; Toyoizumi-Ajisaka, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Arakawa, Y.; Shibayama, K.; Kamachi, K. Prevalence and genetic characterization of pertactin-deficient Bordetella pertussis in Japan. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Octavia, S.; Luu, L.D.W.; Payne, M.; Timms, V.; Tay, C.Y.; Keil, A.D.; Sintchenko, V.; Guiso, N.; Lan, R. Pertactin-Negative and Filamentous Hemagglutinin-Negative Bordetella pertussis, Australia, 2013–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1196–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Hu, D.; Luu, L.D.W.; Octavia, S.; Keil, A.D.; Sintchenko, V.; Tanaka, M.M.; Mooi, F.R.; Robson, J.; Lan, R. Genomic dissection of the microevolution of Australian epidemic Bordetella pertussis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 1460–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, N.; Davies, H.; Morgan, J.; Sundaresan, M.; Tiong, A.; Preston, A.; Bagby, S. Comparative genomics of Bordetella pertussis isolates from New Zealand, a country with an uncommonly high incidence of whooping cough. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, F.; Hou, Y.; Jia, B.; Zhuang, J.; Cao, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Z.; Jia, Z.; et al. Genomic epidemiology and evolution of Bordetella pertussis under the vaccination pressure of acellular vaccines in Beijing, China, 2020–2023. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2025, 14, 2447611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Williams, M.M.; Xiaoli, L.; Simon, A.; Fueston, H.; Tondella, M.L.; Weigand, M.R. Strengthening Bordetella pertussis genomic surveillance by direct sequencing of residual positive specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0165323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, A.; Otsuka, N.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Kamachi, K.; Nishimura, N.; Ozaki, T.; Poolman, J.; Geurtsen, J. Bordetella pertussis population dynamics and phylogeny in Japan after adoption of acellular pertussis vaccines. Microb Genom. 2018, 4, e000180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda-Madej, A.; Łabaz, J.; Topola, E.; Bazan, H.; Viscardi, S. Pertussis-A Re-Emerging Threat Despite Immunization: An Analysis of Vaccine Effectiveness and Antibiotic Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J. Resurgence of pertussis: Epidemiological trends, contributing factors, challenges, and recommendations for vaccination and surveillance. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2513729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.A.; Strong, K.; Cork, S.C.; McAllister, T.A.; Liljebjelke, K.; Zaheer, R.; Checkley, S.L. The Role of Whole Genome Sequencing in the Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistant Enterococcus spp.: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 599285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Yu, A.; Liu, G.; Zheng, B.; Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Molecular epidemiology and genomic features of Bordetella pertussis in Tianjin, China, 2023. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, M.; Barkoff, A.M.; Nyqvist, A.; Savolainen-Kopra, C.; Antikainen, J.; Mertsola, J.; Ivaska, L.; He, Q. Macrolide-resistant Bordetella pertussis strain identified during an ongoing epidemic, Finland, January to October 2024. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, K.K. (Ed.) Evolution of Bordetella pertussis Genome May Play a Role in the Increased Rate of Whooping Cough Cases in the United States; JMU Scholarly Commons: Harrisonburg, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, S.K.; Preston, A. A role for genomics-based studies of Bordetella pertussis adaptation. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 38, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nian, X.; Liu, H.; Cai, M.; Duan, K.; Yang, X. Coping Strategies for Pertussis Resurgence. Vaccines 2023, 11, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.Z.; He, H.Q.; Shu, Q. Resurgence of pertussis: Reasons and coping strategies. World J. Pediatr. 2024, 20, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, T.; Koide, K.; Kido, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Goto, M.; Kenri, T.; Suzuki, H.; Otsuka, N.; Takada, H. Fatal case of macrolide-resistant Bordetella pertussis infection, Japan, 2024. J. Infect. Chemother. 2025, 31, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, K.; Uchitani, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Otsuka, N.; Goto, M.; Kenri, T.; Kamachi, K. Whole-genome comparison of two same-genotype macrolide-resistant Bordetella pertussis isolates collected in Japan. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltermann, L.; Laborda, P.; Irazoqui, O.; Pogrebnyakov, I.; Bendixen, M.P.; Molin, S.; Johansen, H.K.; La Rosa, R. Macrolide resistance through uL4 and uL22 ribosomal mutations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Chen, L.; He, T.; Li, J.; Zou, A.; Li, F.; Chen, F.; Fan, B.; Ni, W.; Xiao, W.; et al. Daily versus three-times-weekly azithromycin in Chinese patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: Protocol for a prospective, open-label and randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; Zhou, J.; Yang, C.; Nijiati, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yan, G.; Lu, G.; Zhai, X.; Wang, C. Molecular Evolution and Increasing Macrolide Resistance of Bordetella pertussis, Shanghai, China, 2016–2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 30, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paireau, J.; Guillot, S.; Aït El Belghiti, F.; Matczak, S.; Trombert-Paolantoni, S.; Jacomo, V.; Taha, M.K.; Salje, H.; Brisse, S.; Lévy-Bruhl, D.; et al. Effect of change in vaccine schedule on pertussis epidemiology in France: A modelling and serological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.D. Pertussis in Young Infants Throughout the World. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, S119–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Driessche, P. Reproduction numbers of infectious disease models. Infect. Dis. Model. 2017, 2, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooi, F.R.; van Loo, I.H.; van Gent, M.; He, Q.; Bart, M.J.; Heuvelman, K.J.; de Greeff, S.C.; Diavatopoulos, D.; Teunis, P.; Nagelkerke, N.; et al. Bordetella pertussis strains with increased toxin production associated with pertussis resurgence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundermann, A.J.; Kumar, P.; Griffith, M.P.; Waggle, K.D.; Rangachar Srinivasa, V.; Raabe, N.; Mills, E.G.; Coyle, H.; Ereifej, D.; Creager, H.M.; et al. Real-Time Genomic Surveillance for Enhanced Healthcare Outbreak Detection and Control: Clinical and Economic Impact. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekola-Ayele, F.; Rotimi, C.N. Translational Genomics in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Opportunities and Challenges. Public Health Genom. 2015, 18, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrichenko, K.; Engdal, E.S.; Marvig, R.L.; Jemt, A.; Vignes, J.M.; Almusa, H.; Saether, K.B.; Briem, E.; Caceres, E.; Elvarsdóttir, E.M.; et al. Recommendations for bioinformatics in clinical practice. Genome Med. 2025, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, E.V.; Cameron, S.K.; Langridge, G.C.; Preston, A. Bacterial genome structural variation: Prevalence, mechanisms, and consequences. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Su, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Yan, R.; Zhu, D.; et al. Immunogenicity and safety of co-purified diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis vaccine in 6-year-old Chinese children. Nat. Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Ma, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Pan, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhao, C.; et al. Real-World Effectiveness of 3 Types of Acellular Pertussis Vaccines Among Children Aged 3 Months-16 Years in Lu’an, China: A Matched Case-Control Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Deng, J.; Yang, Y. Pertussis vaccination in Chinese children with increasing reported pertussis cases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škopová, K.; Holubová, J.; Bočková, B.; Slivenecká, E.; Santos de Barros, J.M.; Staněk, O.; Šebo, P. Less reactogenic whole-cell pertussis vaccine confers protection from Bordetella pertussis infection. mSphere 2025, 10, e0063924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, C. The Path to New Pediatric Vaccines against Pertussis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Pu, W.; Pan, X.; Li, P.; Bai, Q.; Liang, S.; Li, C.; Yu, Y.; Yao, H.; et al. A multi-epitope subunit vaccine providing broad cross-protection against diverse serotypes of Streptococcus suis. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locati, L.; Bottero, D.; Carriquiriborde, F.; López, O.; Pschunder, B.; Zurita, E.; Martin Aispuro, P.; Gaillard, M.E.; Hozbor, D. Harnessing outer membrane vesicles derived from Bordetella pertussis to overcome key limitations of acellular pertussis vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1655910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, Y. Revisiting Whooping Cough: Global Drivers and Implications of Pertussis Resurgence in the Acellular Vaccine Era. Vaccines 2026, 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010035

Zhang S, Xu Y, Xiao Y. Revisiting Whooping Cough: Global Drivers and Implications of Pertussis Resurgence in the Acellular Vaccine Era. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Siheng, Yan Xu, and Ying Xiao. 2026. "Revisiting Whooping Cough: Global Drivers and Implications of Pertussis Resurgence in the Acellular Vaccine Era" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010035

APA StyleZhang, S., Xu, Y., & Xiao, Y. (2026). Revisiting Whooping Cough: Global Drivers and Implications of Pertussis Resurgence in the Acellular Vaccine Era. Vaccines, 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010035