Evaluation of Polymyxin B as a Novel Vaccine Adjuvant and Its Immunological Comparison with FDA-Approved Adjuvants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Formulation of Bacterial Whole-Cell Inactivated N. gonorrhoeae Vaccine Microparticles and Viral Measles Vaccine

2.2.2. Formulation of Adjuvants and Viral Vaccine Microparticles for the H1N1 (Influenza A Strain) Virus, Canine Coronavirus (iCCoV), and Zika Virus

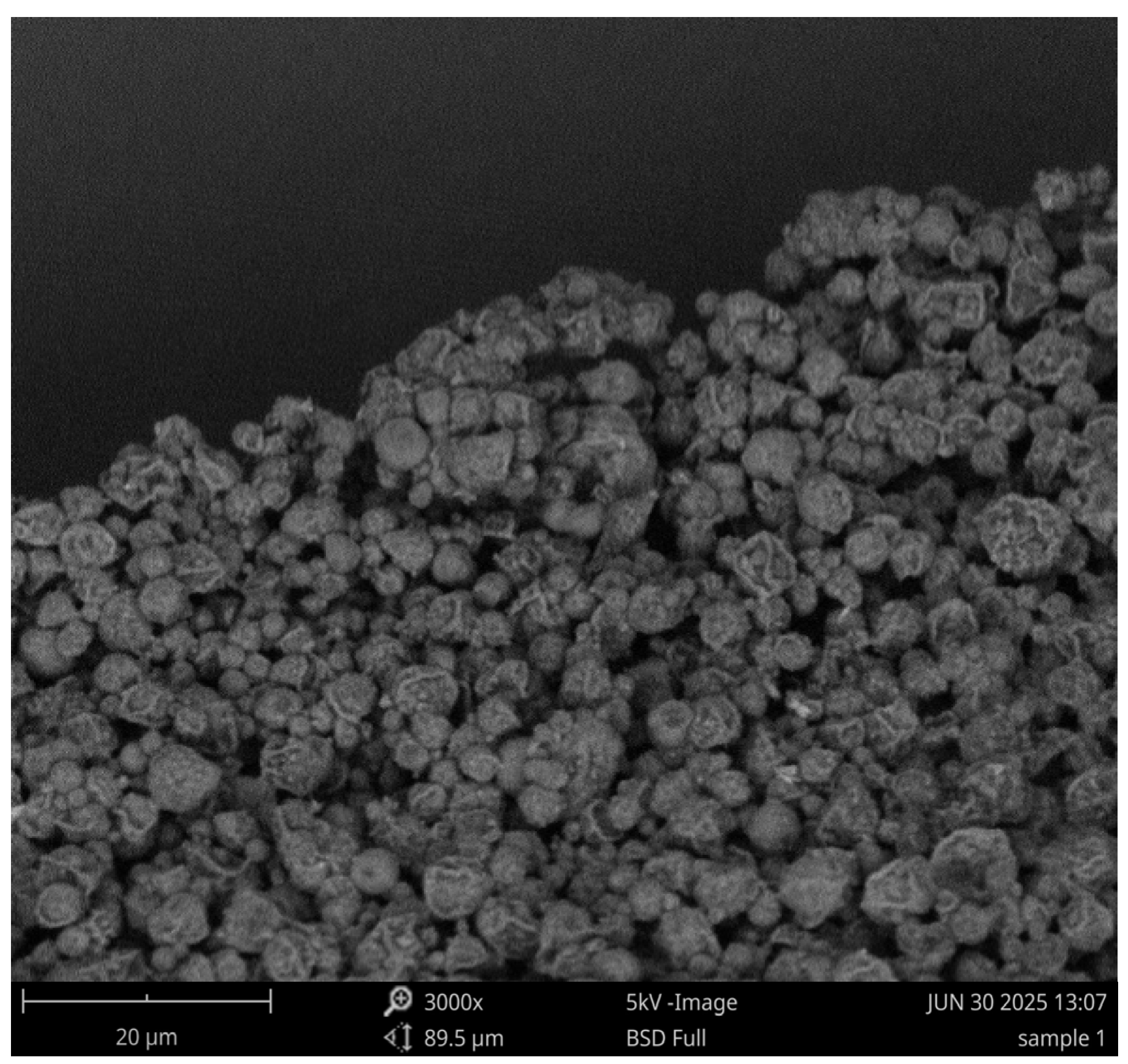

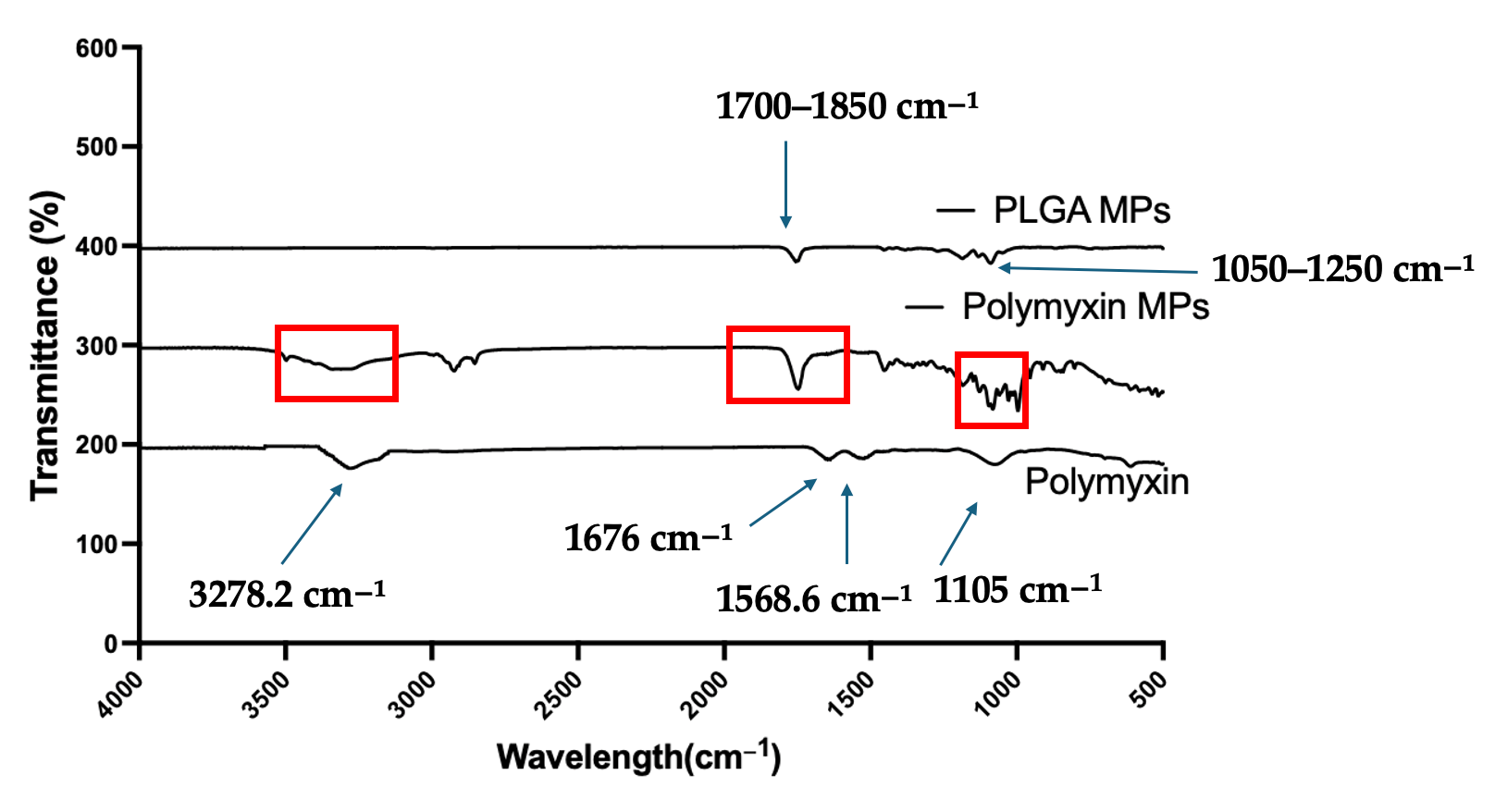

2.2.3. Physicochemical and Morphological Characterization of Polymyxin B Microparticles

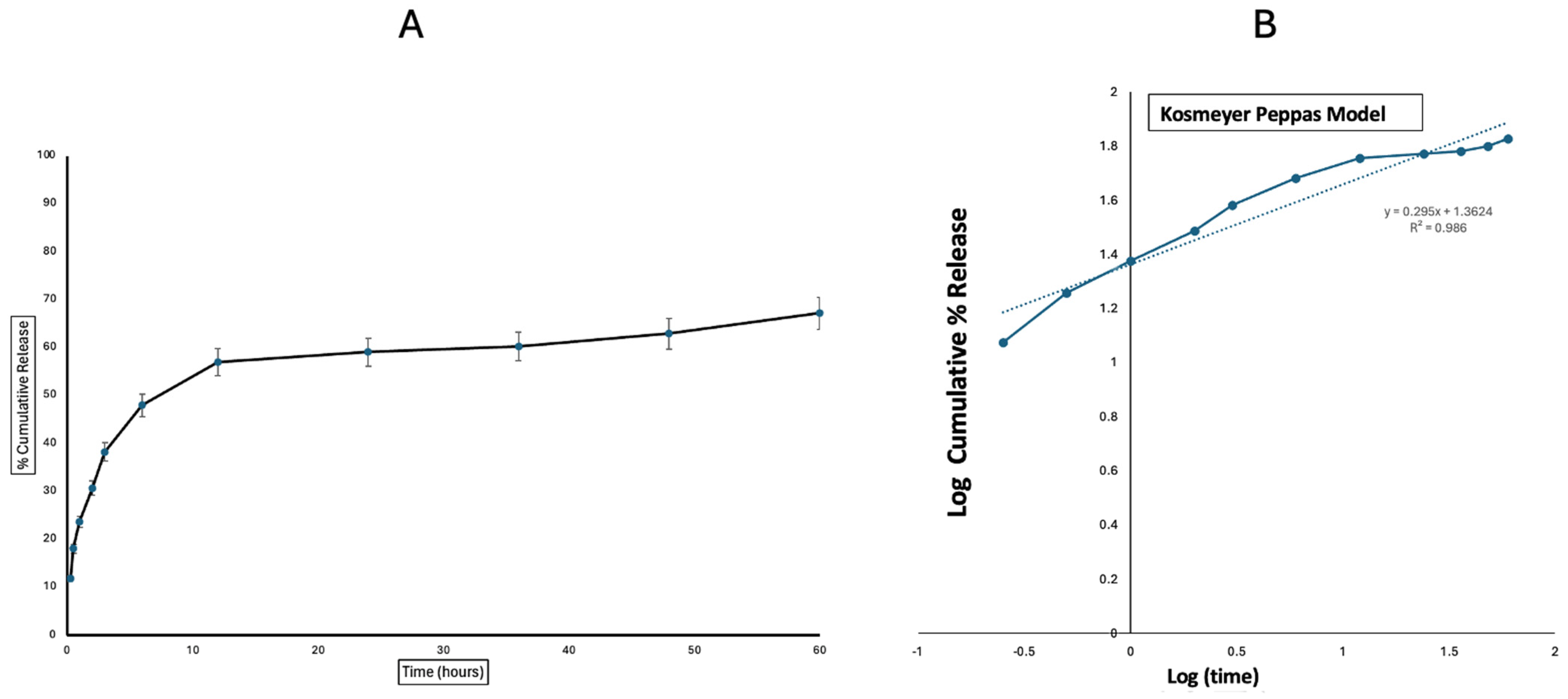

2.2.4. In Vitro Release Profile of Polymyxin Microparticles

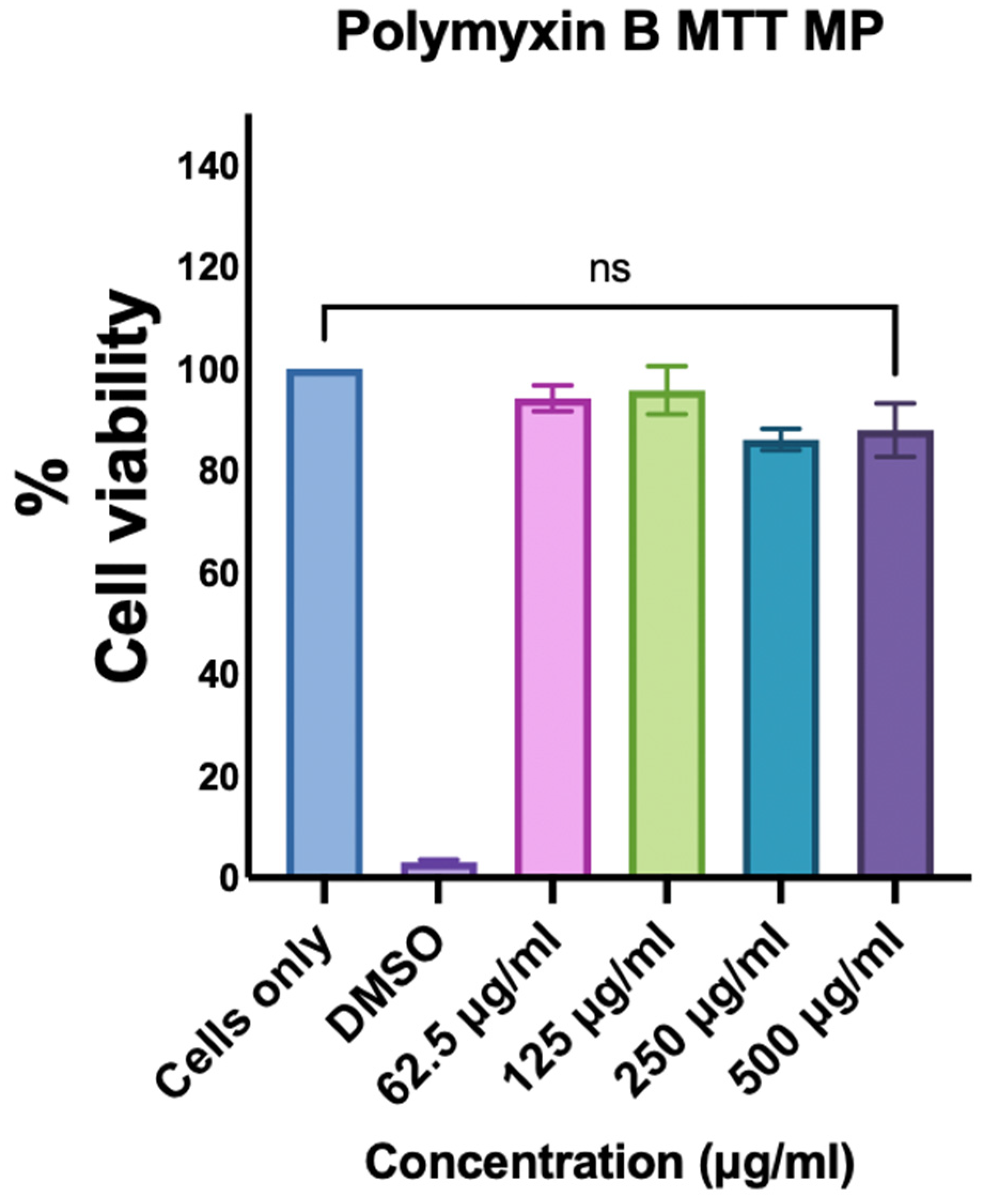

2.2.5. Assessment of the Cytotoxicity of Polymyxin B Microparticles

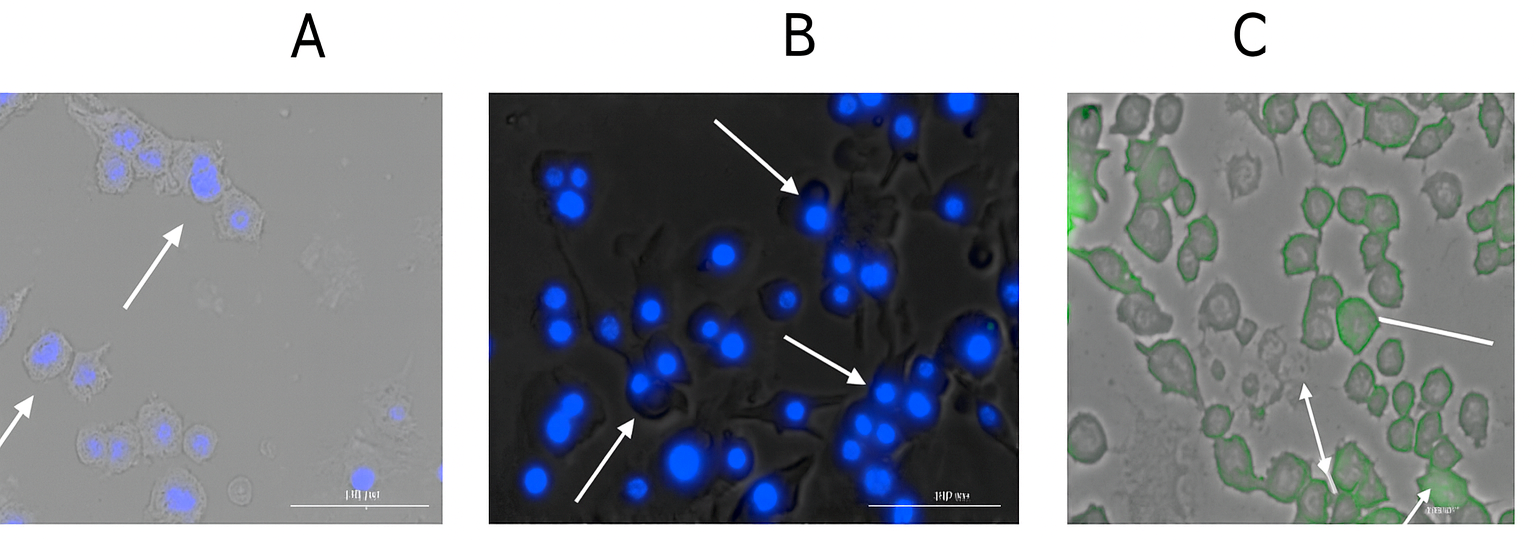

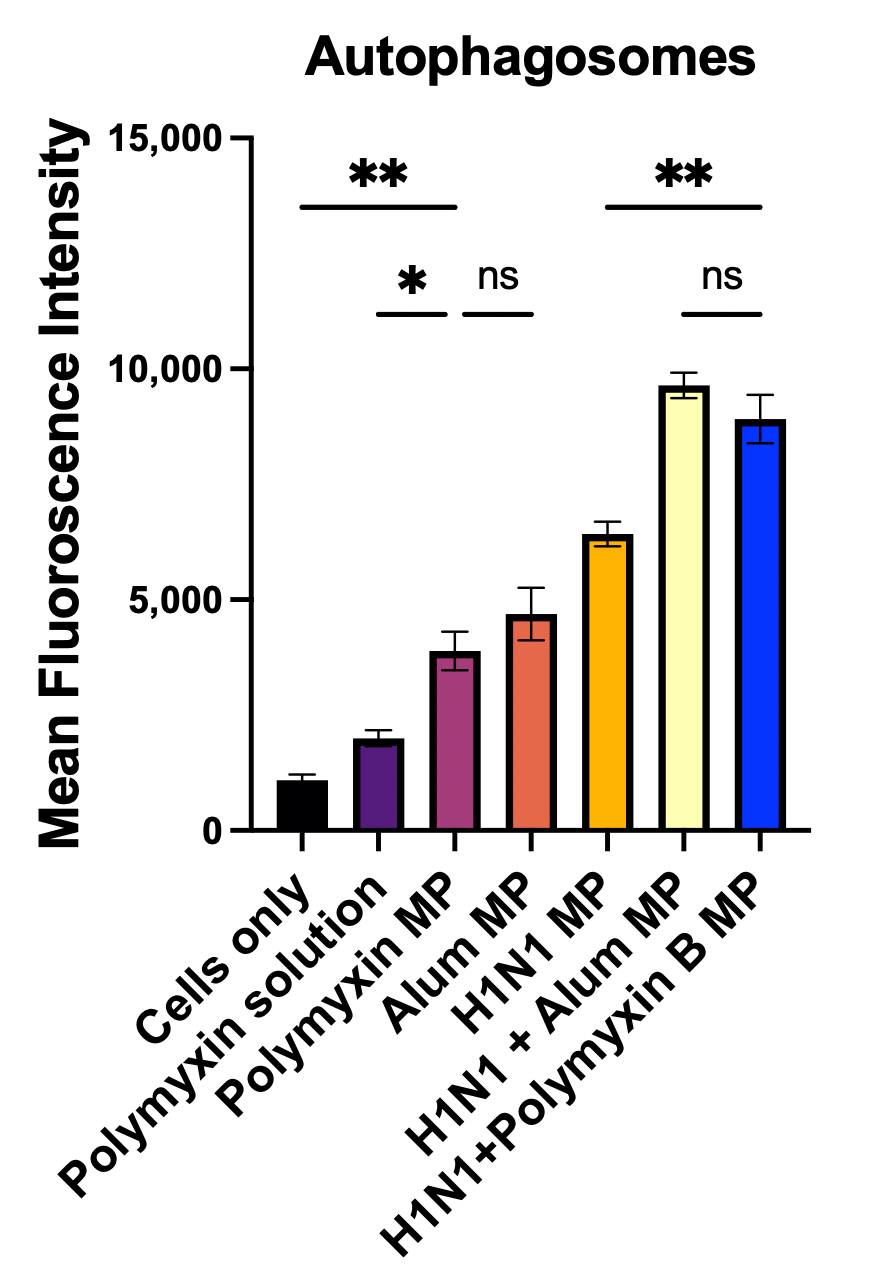

2.2.6. Qualitative and Quantitative Evaluation of Autophagosomes

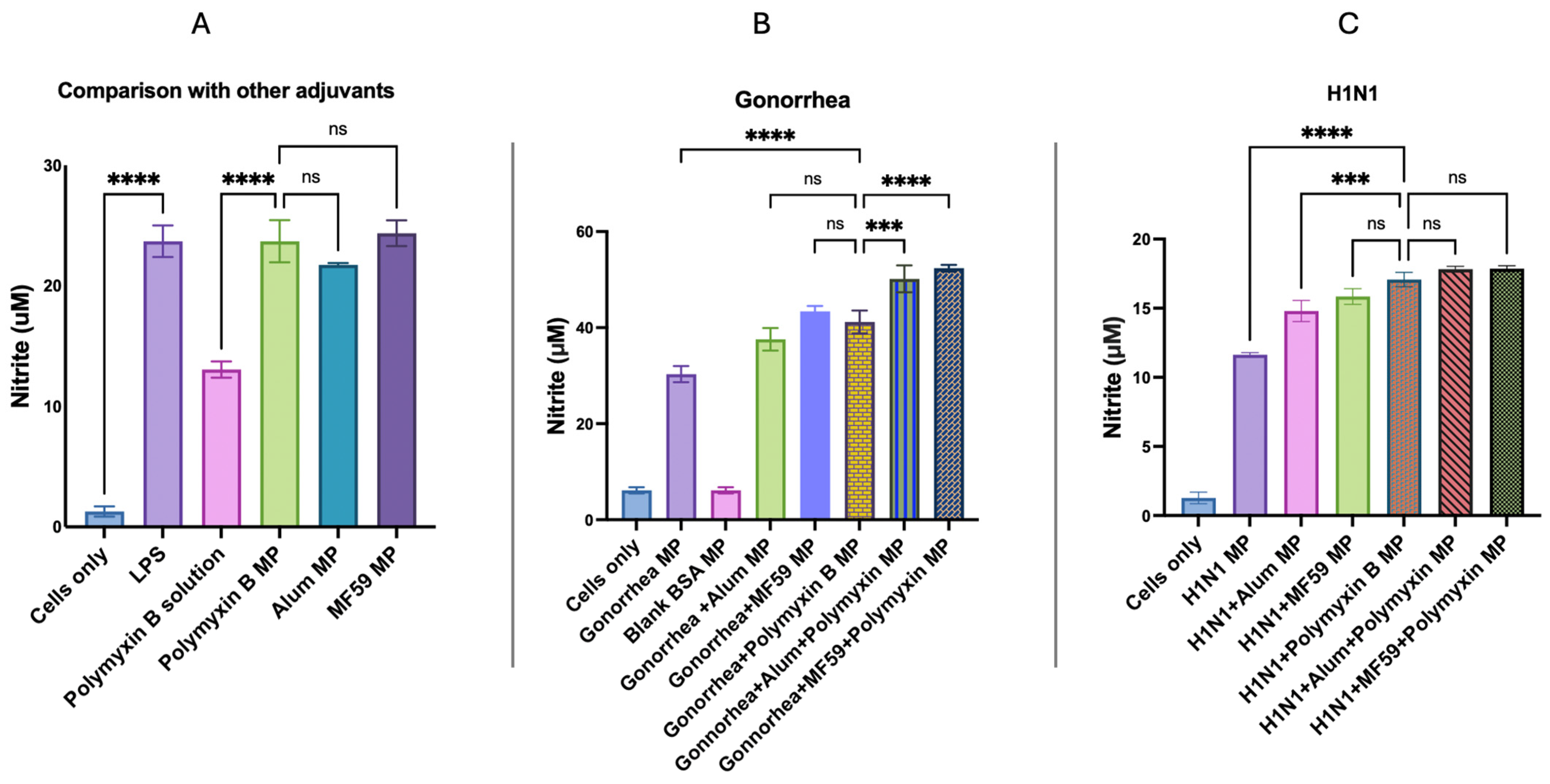

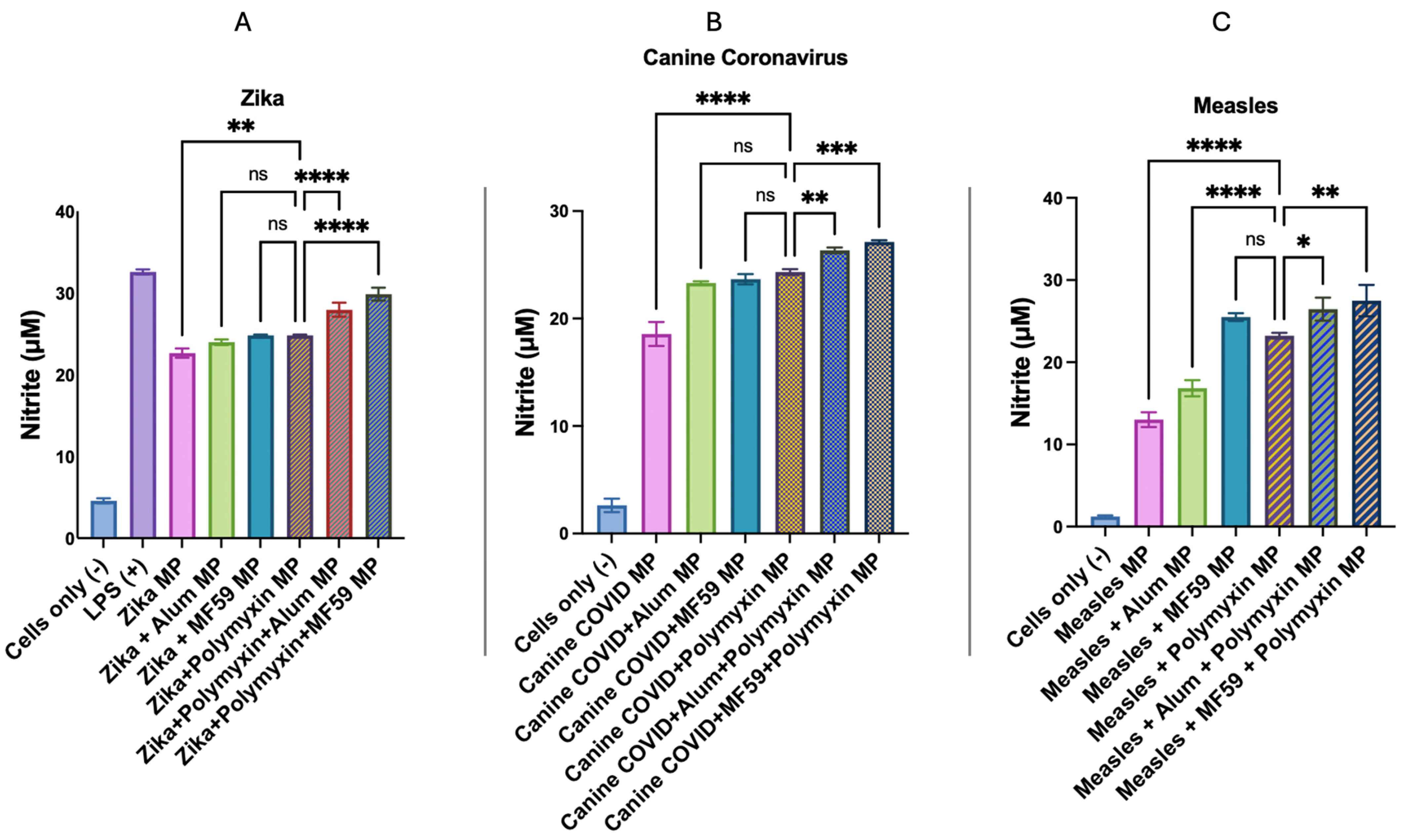

2.2.7. In Vitro Immunogenicity Evaluation of Adjuvant Effect Using Griess Assay for Nitrite Detection

2.2.8. Evaluation of Antigen-Presenting and Co-Stimulatory Molecule Expression via Flow Cytometry

2.2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physiochemical and Morphological Characterization of Polymyxin B Microparticles

3.2. In Vitro Release Profile of Polymyxin Microparticles

3.3. Assessment of the Cytotoxicity of Polymyxin B Microparticles

3.4. Qualitative and Quantitative Evaluation of Autophagosomes

3.5. In Vitro Immunogenicity Evaluation of Adjuvant Effect Using Griess Assay for Nitrite Detection

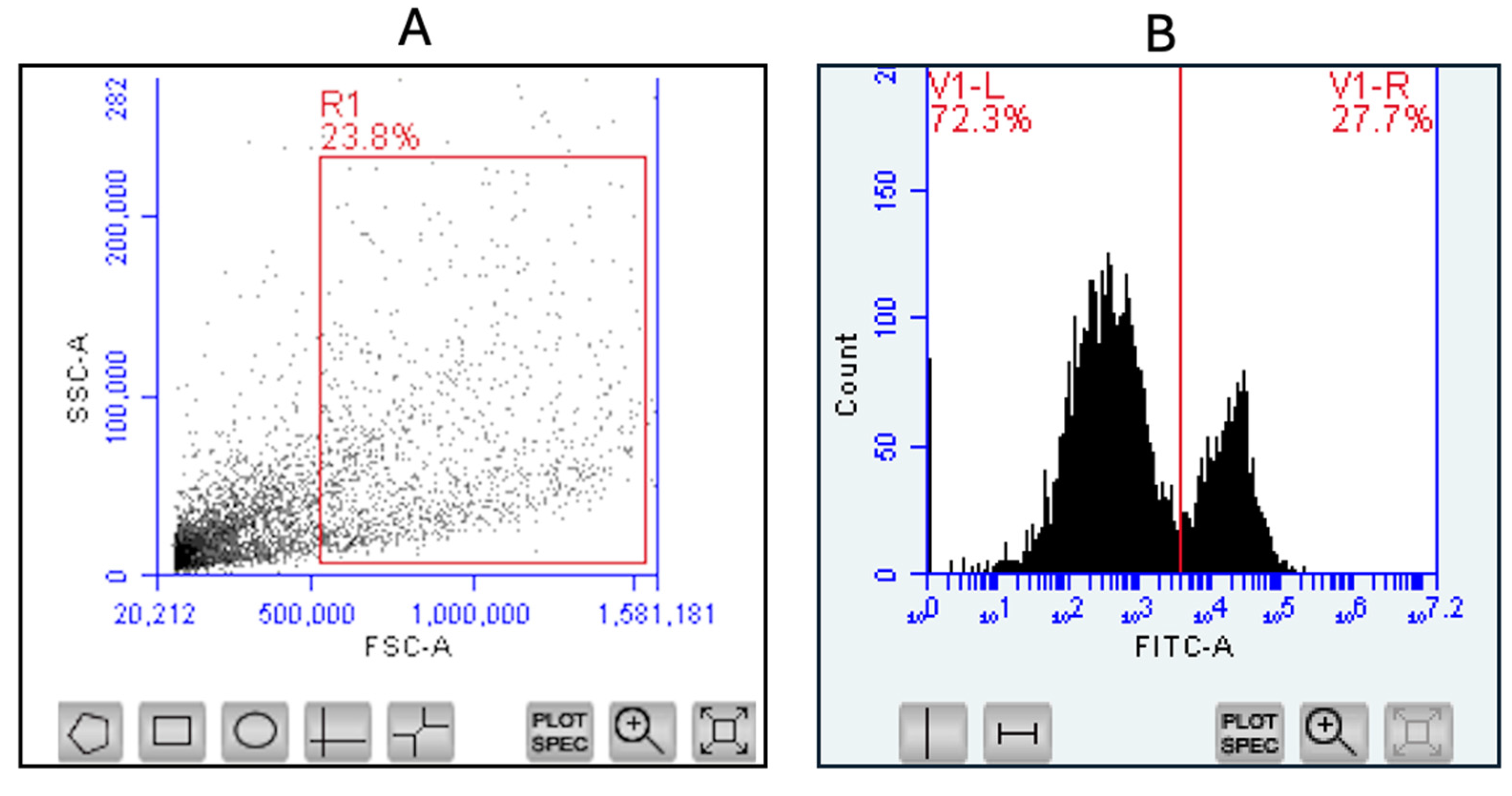

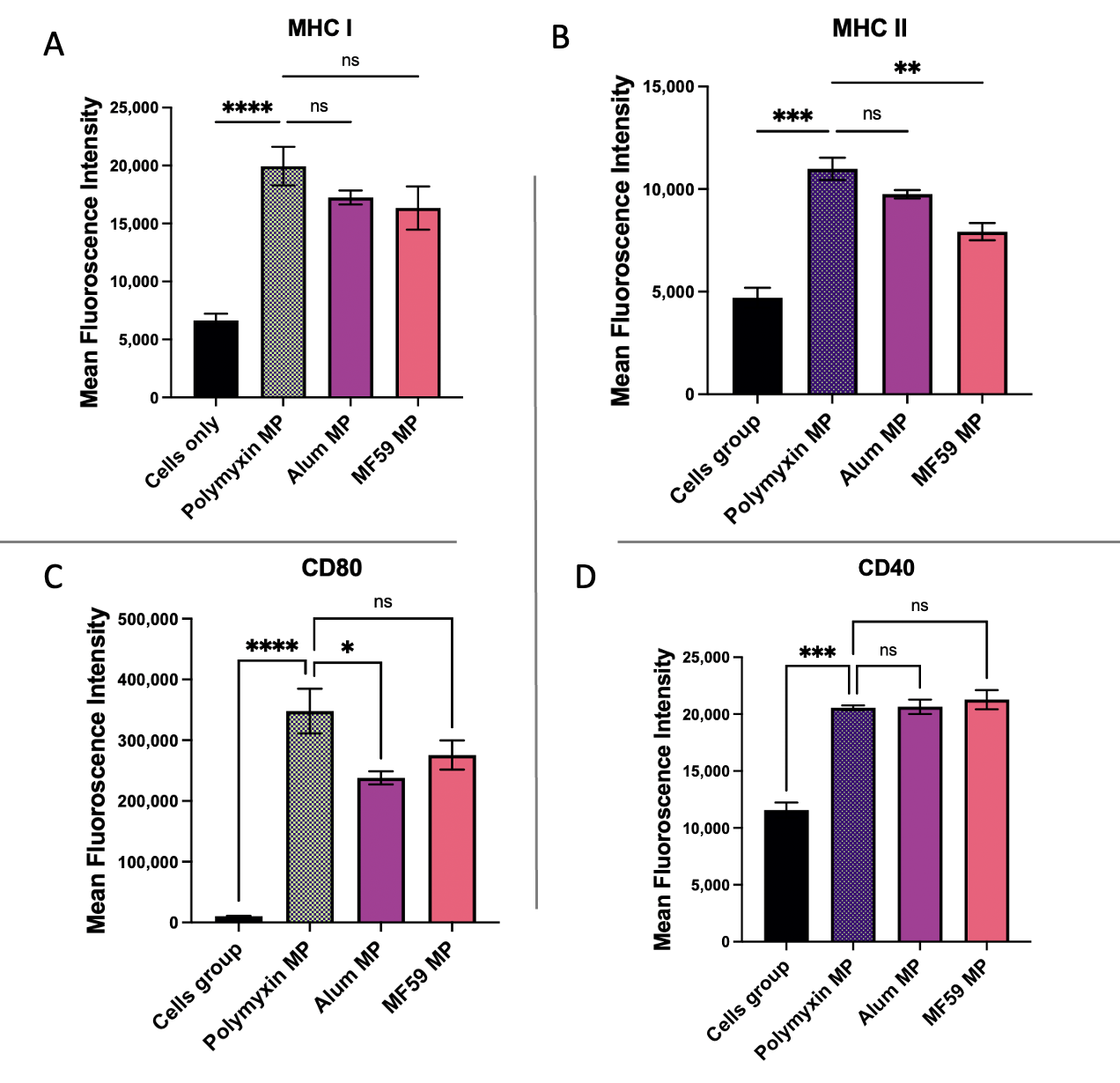

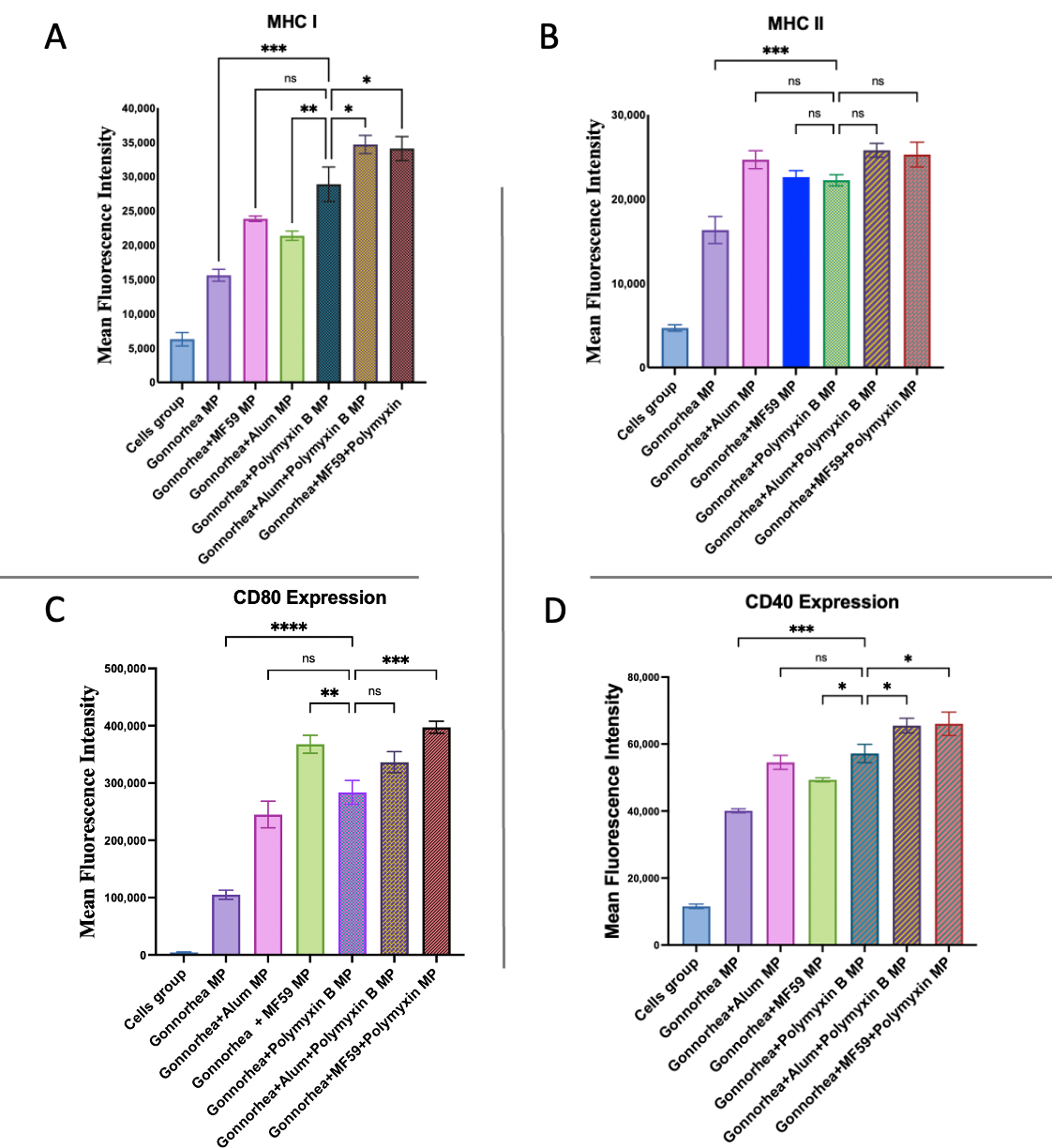

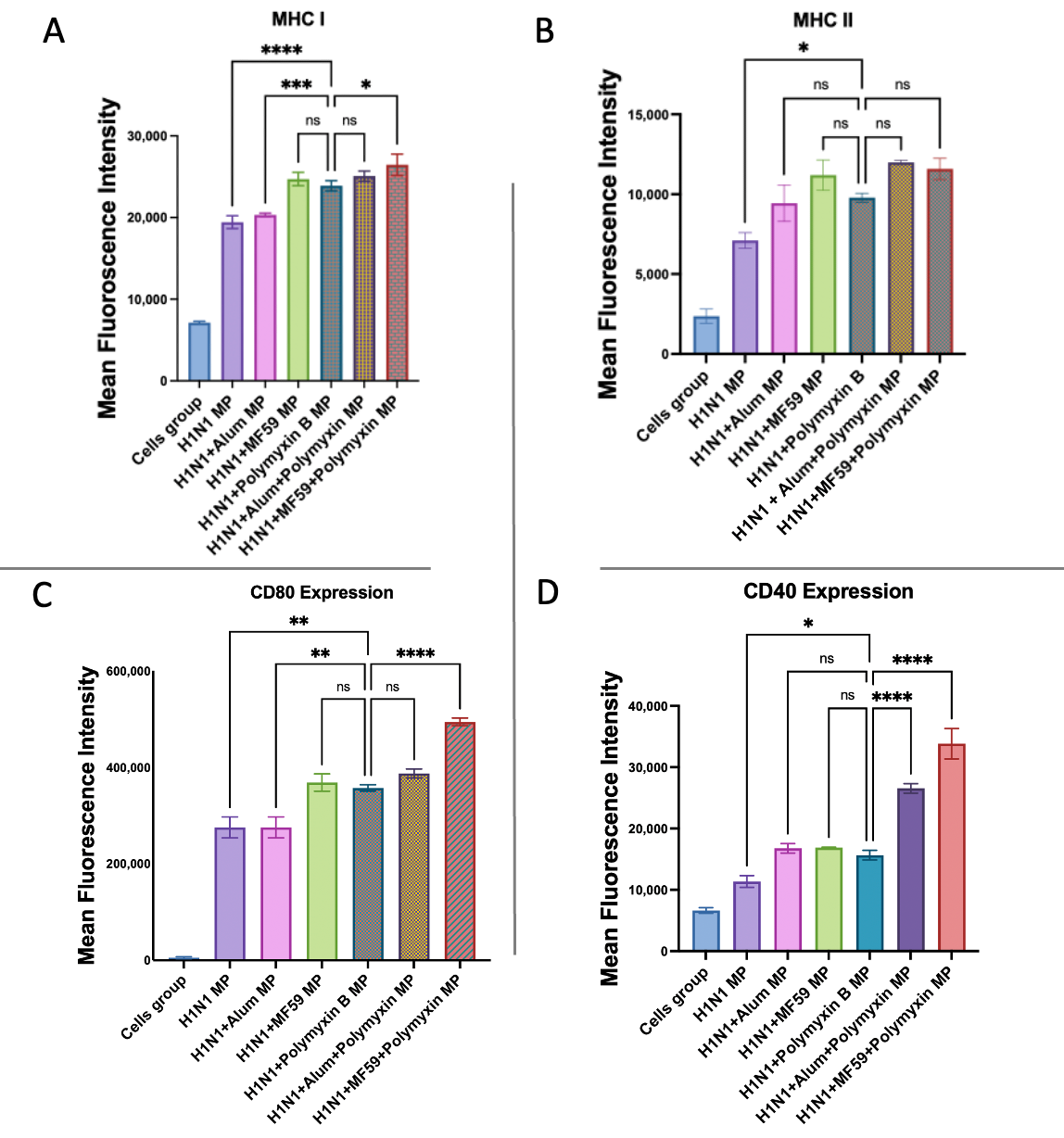

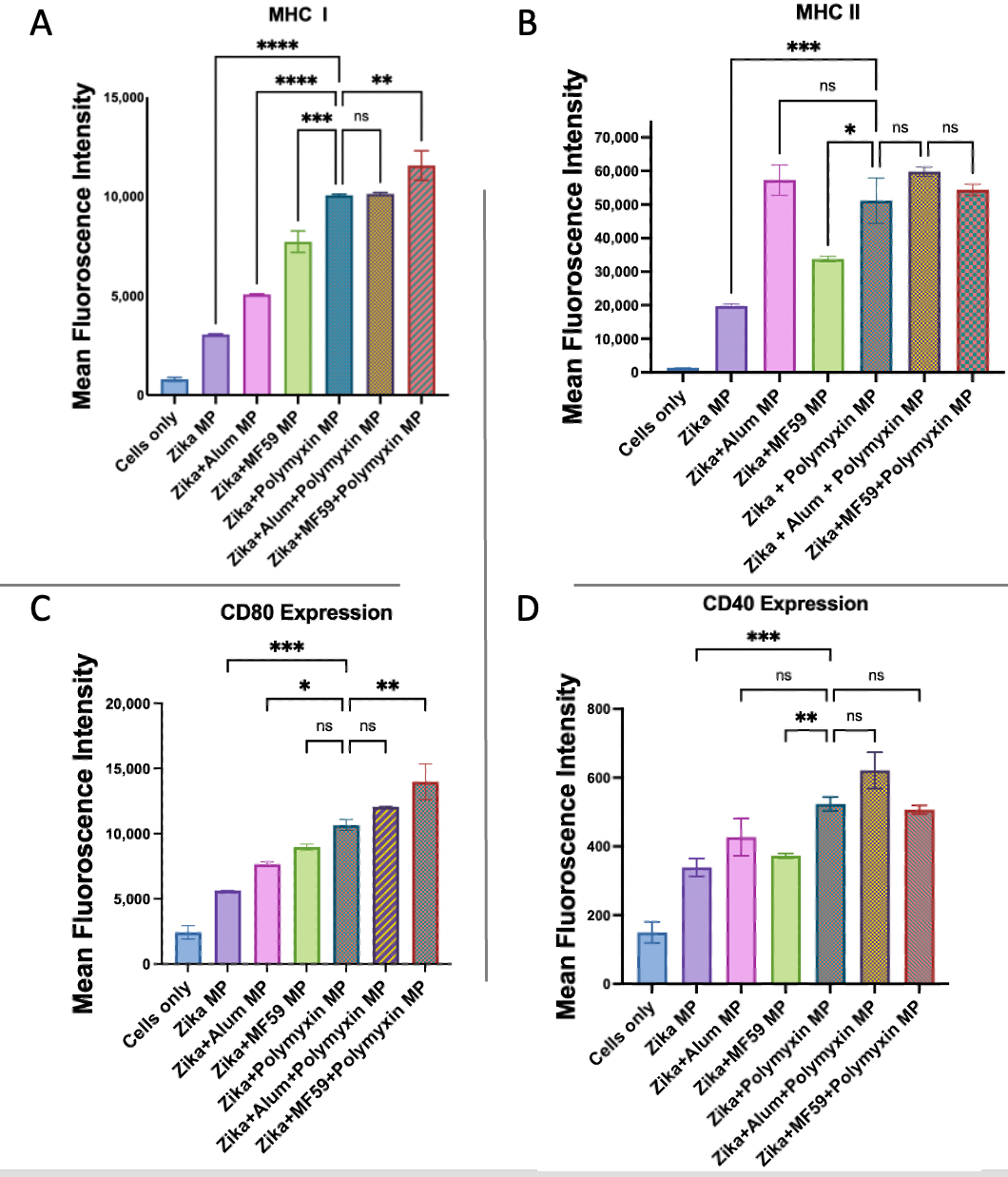

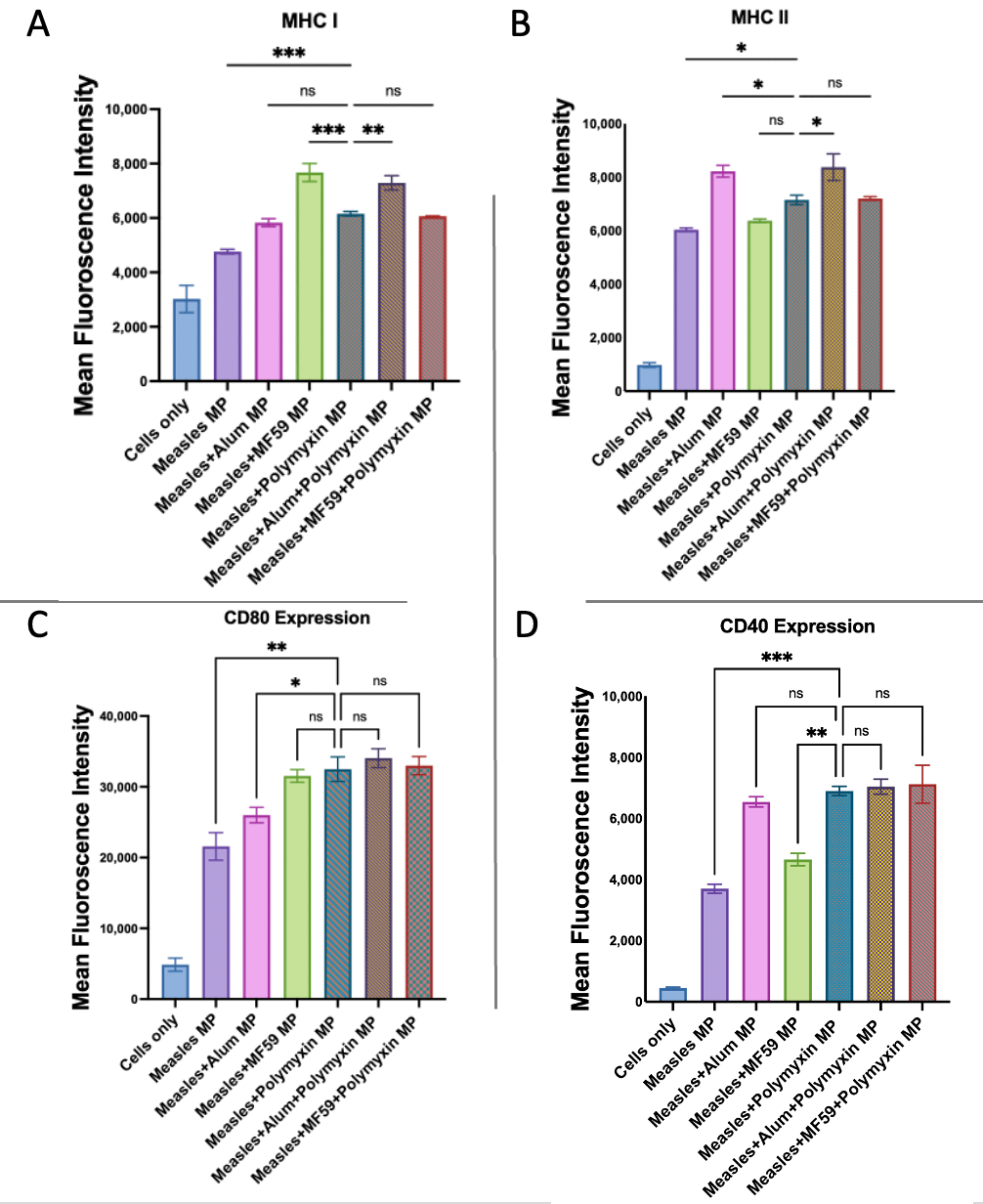

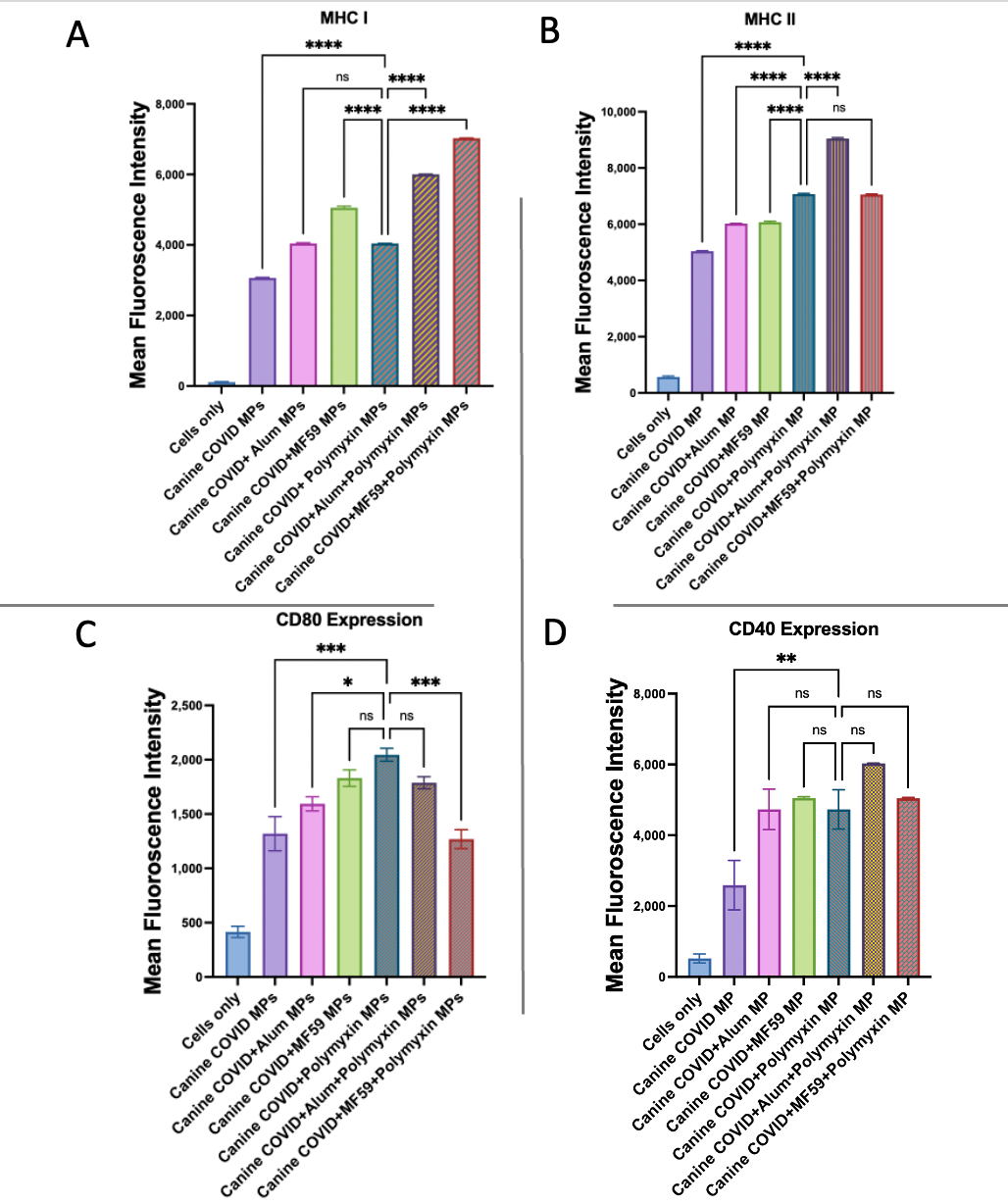

3.6. Evaluation of Antigen-Presenting and Co-Stimulatory Molecule Expression by Flow Cytometry

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, T.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Wei, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tian, X. Vaccine Adjuvants: Mechanisms and Platforms. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; O’Hagan, D.T. Recent Advances in Vaccine Adjuvants. Pharm. Res. 2002, 19, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, R. The Development and Use of Vaccine Adjuvants. Mol. Biotechnol. 2002, 21, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyer-Harini, P.; Ashok-Kumar, H.G.; Kumar, G.P.; Shivakumar, N. An Overview of Immunologic Adjuvants—A Review. J. Vaccines Vaccin. 2013, 4, 1000167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, J.C.; Rodríguez, E.G. Vaccine Adjuvants Revisited. Vaccine 2007, 25, 3752–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffman, R.L.; Sher, A.; Seder, R.A. Vaccine Adjuvants: Putting Innate Immunity to Work. Immunity 2010, 33, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewumi, M.O.; Kumar, A.; Cui, Z. Nano-Microparticles as Immune Adjuvants: Correlating Particle Sizes and the Resultant Immune Responses. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2010, 9, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallapragada, S.K.; Narasimhan, B. Immunomodulatory Biomaterials. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.; Joshi, D.; Chbib, C.; Roni, M.A.; Uddin, M.N. The Autoinducer N-Octanoyl-L-Homoserine Lactone (C8-HSL) as a Potential Adjuvant in Vaccine Formulations. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantis, N.J.; Rol, N.; Corthésy, B. Secretory IgA’s Complex Roles in Immunity and Mucosal Homeostasis in the Gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neutra, M.R.; Kozlowski, P.A. Mucosal Vaccines: The Promise and the Challenge. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, A.K.; Chowdhury, M.Y.E.; Tao, W.; Gill, H.S. Mucosal Vaccine Delivery: Current State and a Pediatric Perspective. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, N.; Yokoyama, T.; Sakai, H.; Sugiyama, I.; Odagiri, T.; Kimura, M.; Hojo, W.; Saino, T.; Muraki, Y. Suitability of Polymyxin B as a Mucosal Adjuvant for Intranasal Influenza and COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, N.; Endo, M.; Kanno, H.; Matsukawa, N.; Tsutsumi, R.; Takeshita, R.; Sato, S. Polymyxins as Novel and Safe Mucosal Adjuvants to Induce Humoral Immune Responses in Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulani, M.; Arte, T.; Ferguson, A.; Pasupuleti, D.; Adediran, E.; Harsoda, Y.; Nicolas McCommon, A.; Gala, R.; D’Souza, M.J. Recent Advancements in Non-Invasive Vaccination Strategies. Vaccines 2025, 13, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Tam, V.H. Polymyxin B: A New Strategy for Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Organisms. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2008, 17, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatto, M.H.; Falci, D.R.; Zavascki, A.P. Clinical Use of Polymyxin B. In Polymyxin Antibiotics: From Laboratory Bench to Bedside; Li, J., Nation, R.L., Kaye, K.S., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1145, pp. 197–218. ISBN 978-3-030-16371-6. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt, J.H.; Harper, M.; Boyce, J.D. Mechanisms of Polymyxin Resistance. In Polymyxin Antibiotics: From Laboratory Bench to Bedside; Li, J., Nation, R.L., Kaye, K.S., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1145, pp. 55–71. ISBN 978-3-030-16371-6. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C.T.; Bachelder, E.M.; Ainslie, K.M. Mast Cell Activators as Adjuvants for Intranasal Mucosal Vaccines. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 672, 125300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpakom, S.; Iorio, F.; Eyers, P.A.; Escott, K.J.; Hopper, S.; Wells, A.; Doig, A.; Guilliams, T.; Latimer, J.; McNamee, C.; et al. Drug Repurposing: Progress, Challenges and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathaneni, V.; Kulkarni, N.S.; Muth, A.; Gupta, V. Drug Repurposing: A Promising Tool to Accelerate the Drug Discovery Process. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 2076–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, M.; Huang, H.; Jin, W.-L. Drug Repurposing for Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Gulani, M.; Vijayanand, S.; Arte, T.; Adediran, E.; Pasupuleti, D.; Patel, P.; Ferguson, A.; Uddin, M.; Zughaier, S.M.; et al. An Intranasal Quadruple Variant Vaccine Approach Using SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A: Delta, Omicron, H1N1and H3N2. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 683, 126043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arte, T.M.; Patil, S.R.; Adediran, E.; Singh, R.; Bagwe, P.; Gulani, M.A.; Pasupuleti, D.; Ferguson, A.; Zughaier, S.M.; D’Souza, M.J. Microneedle Delivery of Heterologous Microparticulate COVID-19 Vaccine Induces Cross Strain Specific Antibody Levels in Mice. Vaccines 2025, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adediran, E.; Vijayanand, S.; Kale, A.; Gulani, M.; Wong, J.C.; Escayg, A.; Murnane, K.S.; D’Souza, M.J. Microfluidics-Assisted Formulation of Polymeric Oxytocin Nanoparticles for Targeted Brain Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Viswaroopan, N.; Kshirsagar, S.M.; Khan, J.; Mohiuddin, S.; Srivastava, R.K.; Athar, M.; Banga, A.K. Sustained Delivery of 4-Phenylbutyric Acid via Chitosan Nanoparticles in Foam for Decontamination and Treatment of Lewisite-Mediated Skin Injury. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 682, 125928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewpaiboon, S.; Srichana, T. Formulation Optimization and Stability of Polymyxin B Based on Sodium Deoxycholate Sulfate Micelles. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 2249–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the MTT Assay. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018, 2018, pdb.prot095505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münz, C. Antigen Processing for MHC Class II Presentation via Autophagy. Front. Immun. 2012, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münz, C. Autophagy Proteins in Antigen Processing for Presentation on MHC Molecules. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 272, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghislat, G.; Lawrence, T. Autophagy in Dendritic Cells. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uehara, E.U.; Shida, B.D.S.; De Brito, C.A. Role of Nitric Oxide in Immune Responses against Viruses: Beyond Microbicidal Activity. Inflamm. Res. 2015, 64, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmölz, L.; Wallert, M.; Lorkowski, S. Optimized Incubation Regime for Nitric Oxide Measurements in Murine Macrophages Using the Griess Assay. J. Immunol. Methods 2017, 449, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, D.; D’Souza, M.; Ferguson, A.; Gulani, M.A.; Patel, P.; Singh, R.; Adediran, E.; Vijayanand, S.; Arte, T.M.; D’Souza, M. 3D-Printed Oral Disintegrating Films of Brain-Targeted Acetyl Salicylic Acid Nanoparticles for Enhanced CNS Delivery in Ischemic Stroke. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Illangakoon, U.E.; Harker, A.H.; Thrasivoulou, C.; Parhizkar, M.; Edirisinghe, M.; Luo, C. Copolymer Composition and Nanoparticle Configuration Enhance in Vitro Drug Release Behavior of Poorly Water-Soluble Progesterone for Oral Formulations. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 5389–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirooznia, N.; Hasannia, S.; Lotfi, A.S.; Ghanei, M. Encapsulation of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin in PLGA Nanoparticles: In Vitro Characterization as an Effective Aerosol Formulation in Pulmonary Diseases. J. Nanobiotechnol 2012, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğrak, U.; Aksungur, A.; Akyüz, S.; Şen, H.; Seyhan, F. Understanding the Rise of Vaccine Refusal: Perceptions, Fears, and Influences. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Makino-Okamura, C.; Lin, Q.; Wang, M.; Shoemaker, J.E.; Kurosaki, T.; Fukuyama, H. Repurposing the Psoriasis Drug Oxarol to an Ointment Adjuvant for the Influenza Vaccine. Int. Immunol. 2020, 32, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B. Vaccine Safety in an Era of Novel Vaccines: A Proposed Research Agenda. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovsky, N. Comparative Safety of Vaccine Adjuvants: A Summary of Current Evidence and Future Needs. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinani, G.; Şenel, S. Advances in Vaccine Adjuvant Development and Future Perspectives. Drug Deliv. 2025, 32, 2517137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellano, G.; Abreu, H.; Casale, C.; Dianzani, U.; Chiocchetti, A. Nano-Microparticle Platforms in Developing Next-Generation Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.B.; Geary, S.M.; Salem, A.K. Biodegradable Particles as Vaccine Delivery Systems: Size Matters. AAPS J. 2013, 15, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adediran, E.; Arte, T.; Pasupuleti, D.; Vijayanand, S.; Singh, R.; Patel, P.; Gulani, M.; Ferguson, A.; Uddin, M.; Zughaier, S.M.; et al. Delivery of PLGA-Loaded Influenza Vaccine Microparticles Using Dissolving Microneedles Induces a Robust Immune Response. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayanand, S.; Patil, S.; Joshi, D.; Menon, I.; Braz Gomes, K.; Kale, A.; Bagwe, P.; Yacoub, S.; Uddin, M.N.; D’Souza, M.J. Microneedle Delivery of an Adjuvanted Microparticulate Vaccine Induces High Antibody Levels in Mice Vaccinated against Coronavirus. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, A.; Joshi, D.; Menon, I.; Bagwe, P.; Patil, S.; Vijayanand, S.; Braz Gomes, K.; D’Souza, M. Novel Microparticulate Zika Vaccine Induces a Significant Immune Response in a Preclinical Murine Model after Intramuscular Administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 624, 121975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hammadi, M.M.; Arias, J.L. Recent Advances in the Surface Functionalization of PLGA-Based Nanomedicines. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, S.; Maghsoudnia, N.; Eftekhari, R.B.; Dorkoosh, F. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Systems. In Characterization and Biology of Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 47–76. ISBN 978-0-12-814031-4. [Google Scholar]

- He, A.; Li, X.; Dai, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, M.; Wen, Z.; Mou, Y.; Dong, H. Nanovaccine-Based Strategies for Lymph Node Targeted Delivery and Imaging in Tumor Immunotherapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohrey, S.; Chourasiya, V.; Pandey, A. Polymeric Nanoparticles Containing Diazepam: Preparation, Optimization, Characterization, in-Vitro Drug Release and Release Kinetic Study. Nano Converg. 2016, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.T.; Di Pasquale, A.; Yarzabal, J.P.; Garçon, N. Safety Assessment of Adjuvanted Vaccines: Methodological Considerations. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 11, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odagiri, T.; Yoshino, N.; Sasaki, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Muraki, Y. Polymyxin B as a Novel Mucosal Adjuvant for the Intranasal Whole Inactivated Influenza Vaccine. Vaccine 2025, 64, 127750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, M.; Thompson, C.B. Autophagy: Basic Principles and Relevance to Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2008, 3, 427–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireland, J.M.; Unanue, E.R. Autophagy in Antigen-Presenting Cells Results in Presentation of Citrullinated Peptides to CD4 T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 2625–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, N.; Kundu, A. Nanotechnology Platform for Advancing Vaccine Development against the COVID-19 Virus. Diseases 2023, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canthaboo, C.; Xing, D.; Wei, X.Q.; Corbel, M.J. Investigation of Role of Nitric Oxide in Protection from Bordetella pertussis Respiratory Challenge. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, E.; O’Farrell, P.H. Nitric Oxide Contributes to Induction of Innate Immune Responses to Gram-Negative Bacteria in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, E.W. The MHC Class I Antigen Presentation Pathway: Strategies for Viral Immune Evasion. Immunology 2003, 110, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesmiyanov, P.P. Antigen Presentation and Major Histocompatibility Complex. In Encyclopedia of Infection and Immunity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 90–98. ISBN 978-0-323-90303-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, M.; Abualrous, E.T.; Sticht, J.; Álvaro-Benito, M.; Stolzenberg, S.; Noé, F.; Freund, C. Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Class I and MHC Class II Proteins: Conformational Plasticity in Antigen Presentation. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, P.; Shin, E.-C.; Perosa, F.; Vacca, A.; Dammacco, F.; Racanelli, V. MHC Class I Antigen Processing and Presenting Machinery: Organization, Function, and Defects in Tumor Cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-C.; Dzhagalov, I.; Chen, N.-J.; Lin, C.-H.; Lin, C.-C.; Chen, S.-T.; Chen, K.-H.; Fu, S.-L. Vaccine Adjuvant Activity of a TLR4-Activating Synthetic Glycolipid by Promoting Autophagy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Groups | Dose of Microparticles/Well |

|---|---|

| Alum MPs | 100 µg/well |

| MF59 MPs | 100 µg/well |

| Polymyxin MPs | 100 µg/well |

| Gonorrhea MPs | 100 µg/well |

| Gonorrhea MP + Alum MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Gonorrhea MP + MF59 MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Gonorrhea MP + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Gonorrhea MP + Alum + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Gonorrhea MP + MF59 + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| H1N1 MPs | 100 µg/well |

| H1N1 MPs + Alum MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| H1N1 MPs + MF59 MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| H1N1 MPs + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| H1N1 MPs + Alum + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| H1N1 MPs + MF59 + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Zika MPs | 100 µg/well |

| Zika MPs + Alum MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Zika MPs + MF59 MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Zika MPs + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Zika MPs + Alum + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Zika MPs + MF59 + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Measles MPs | 100 µg/well |

| Measles MPs + Alum MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Measles MPs + MF59 MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Measles MPs + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Measles MPs + Alum + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Measles MPs + MF59 + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Canine Coronavirus MPs | 100 µg/well |

| Canine Coronavirus MPs + Alum MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Canine Coronavirus MPs + MF59 MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Canine Coronavirus MPs + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 50 µg/well |

| Canine Coronavirus MPs + Alum + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Canine Coronavirus MPs + MF59 + Polymyxin B MPs | 100 µg/well + 25 µg/well + 25 µg/well |

| Parameter | Polymyxin MPs |

|---|---|

| Size | 2017 ± 300.7 nm |

| % Recovery yield | 78% ± 5% |

| Polydispersity index | 0.296 ± 0.0014 |

| Zeta potential | −22.6 ± 4.1 mV |

| Model | R2 |

|---|---|

| Zero-order | 0.671 |

| First-order | 0.13 |

| Higuchi | 0.423 |

| Korsmeyer–Peppas | 0.986 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gulani, M.; Harsoda, Y.; Arte, T.; D’Souza, M.J.; Bagwe, P.; Adediran, E.; D’Souza, N.; Pasupuleti, D. Evaluation of Polymyxin B as a Novel Vaccine Adjuvant and Its Immunological Comparison with FDA-Approved Adjuvants. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121232

Gulani M, Harsoda Y, Arte T, D’Souza MJ, Bagwe P, Adediran E, D’Souza N, Pasupuleti D. Evaluation of Polymyxin B as a Novel Vaccine Adjuvant and Its Immunological Comparison with FDA-Approved Adjuvants. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121232

Chicago/Turabian StyleGulani, Mahek, Yash Harsoda, Tanisha Arte, Martin J. D’Souza, Priyal Bagwe, Emmanuel Adediran, Nigel D’Souza, and Dedeepya Pasupuleti. 2025. "Evaluation of Polymyxin B as a Novel Vaccine Adjuvant and Its Immunological Comparison with FDA-Approved Adjuvants" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121232

APA StyleGulani, M., Harsoda, Y., Arte, T., D’Souza, M. J., Bagwe, P., Adediran, E., D’Souza, N., & Pasupuleti, D. (2025). Evaluation of Polymyxin B as a Novel Vaccine Adjuvant and Its Immunological Comparison with FDA-Approved Adjuvants. Vaccines, 13(12), 1232. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121232