Dualistic Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among University Students in China: From Perceived Personal Benefits to External Reasons of Perceived Social Benefits, Collectivism, and National Pride

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Background Characteristics

2.2.2. Behavioral Intention of COVID-19 Vaccination

2.2.3. Perceived Personal Benefits of COVID-19 Vaccination

2.2.4. Perceived Social Benefits of COVID-19 Vaccination

2.2.5. Collectivism

2.2.6. National Pride

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Background Characteristics

3.1.2. Behavioral Intention of COVID-19 Vaccination

3.2. Factors of Behavioral Intention of COVID-19 Vaccination

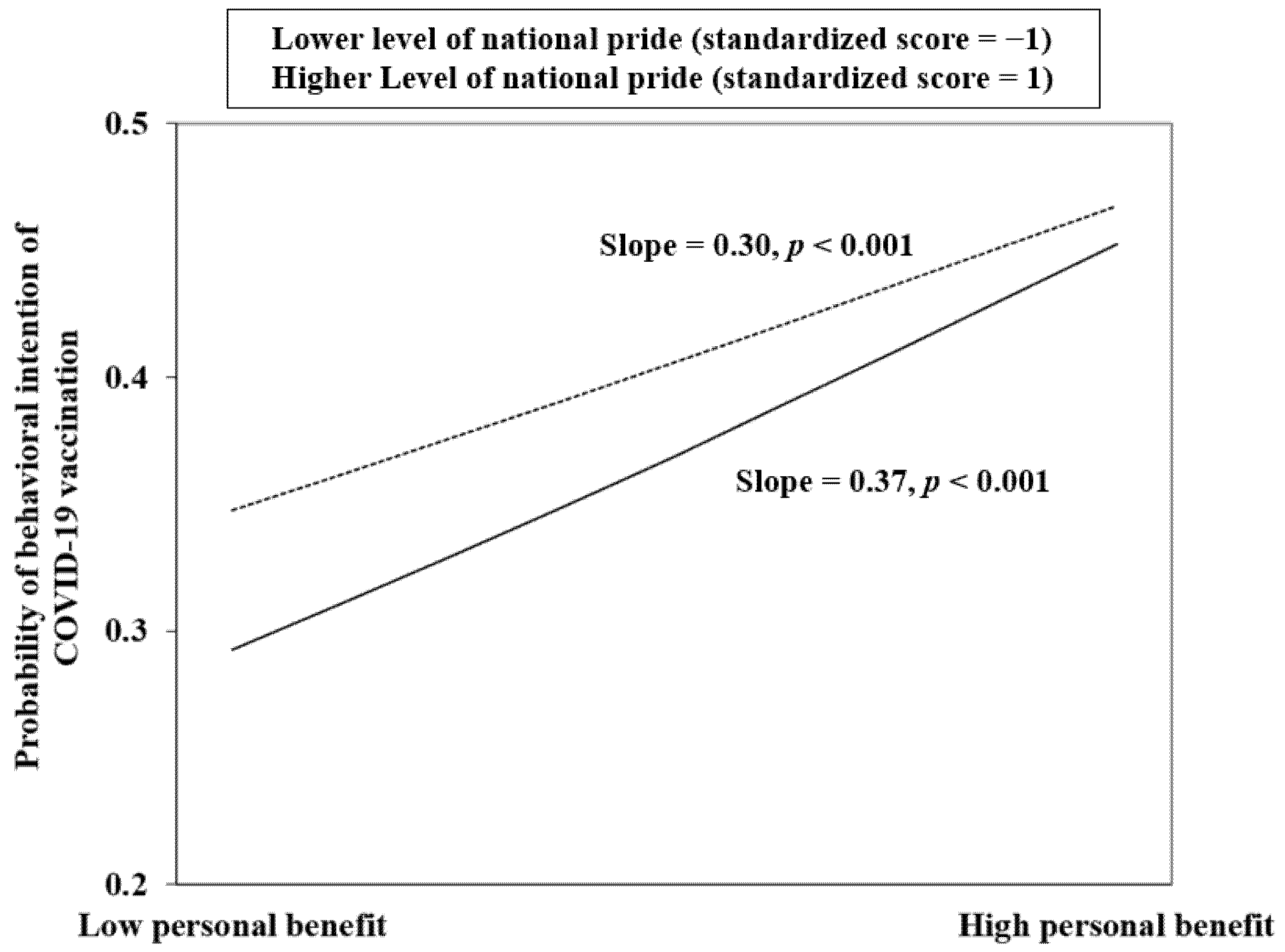

3.3. Interaction Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Rappuoli, R.; Mandl, C.W.; Black, S.; De Gregorio, E. Vaccines for the twenty-first century society. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.N.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W.; Jing, Q.L.; Zhang, C.H.; Qin, P.Z.; Guan, W.J.; Gan, L.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, W.H.; et al. Effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines against the Delta variant infection in Guangzhou: A test-negative case-control real-world study. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Smith, L.E.; Sim, J.; Amlôt, R.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Rubin, G.J.; Sevdalis, N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 17, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Han, B.; Zhao, T.; Liu, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Xie, M.; Liu, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. Vaccination willingness, vaccine hesitancy, and estimated coverage at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: A national cross-sectional study. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Q.H.; Yang, J.; Dong, K.G.; Chen, X.H.; Bai, X.F.; Chen, X.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Viboud, C.; Ajelli, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of target population sizes for COVID-19 vaccination: Descriptive study. BMJ—Brit. Med. J. 2020, 371, m4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanche, S.; Lin, Y.T.; Xu, C.; Romero-Severson, E.; Hengartner, N.; Ke, R. High Contagiousness and Rapid Spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Wong, P.F.; Lee, H.Y.; AbuBakar, S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, P.K.-h.; Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Xie, L.; Lau, J.T.F. Intention to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccination in China: Application of the Diffusion of Innovations Theory and the Moderating Role of Openness to Experience. Vaccines 2021, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.K.; Wei, W.I.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lee, S.S. Editor’s Choice: Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: A survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A.; Penner, L. The Social Psychology of Prosocial Behavior; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, P.K.H.; Wong, C.H.W.; Lam, E.H.K. Can the Health Belief Model and moral responsibility explain influenza vaccination uptake among nurses? J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 1188–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerend, M.A.; Shepherd, J.E. Erratum to: Predicting Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake in Young Adult Women: Comparing the Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 44, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, M.C.S.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Huang, J.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Law, K.; Chong, M.K.C.; Ng, R.W.Y.; Lai, C.K.C.; Boon, S.S.; Lau, J.T.F.; et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: A population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Luo, S.; Mo, P.K.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Lau, J.T. Prosociality and Social Responsibility Were Associated with Intention of COVID-19 Vaccination Among University Students in China. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, x, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim, H.; Gaur, A.H.; McCullers, J.A. Motivating factors for high rates of influenza vaccination among healthcare workers. Vaccine 2011, 29, 5963–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vietri, J.T.; Li, M.; Galvani, A.P.; Chapman, G.B. Vaccinating to help ourselves and others. Med. Decis. Mak. 2012, 32, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Albarracín, D. Concerns for others increase the likelihood of vaccination against influenza and COVID-19 more in sparsely rather than densely populated areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2007538118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G. Understanding public perceptions of benefits and risks of childhood vaccinations in the United States. RiskAnal. Off. Publ. Soc. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.B. Understanding Collective Pride and Group Identity: New Directions in Emotion Theory, Research and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi, I. Social Capital and Community Effects on Population and Individual Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 896, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Tseng, K.C.; Yen, C.H.; Yang, L.H. Social capital and health-protective behavior intentions in an influenza pandemic. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biddlestone, M.; Green, R.; Douglas, K.M. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 59, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Cosme, D.; Andrews, M.E.; Mattan, B.D.; Falk, E.B. Cultural influence on COVID-19 cognitions and growth speed: The role of cultural collectivism. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, F.; Andrieu, E. Bowling together by bowling alone: Social capital and COVID-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A. Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oyserman, D.; Kemmelmeier, M.; Coon, H.M. Cultural psychology, a new look: Reply to Bond (2002), Fiske (2002), Kitayama (2002), and Miller (2002). Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mascolo, M.F.; Fischer, K.W. Developmental transformations in appraisals for pride, shame, and guilt. In Self-Conscious Emotions: The Psychology of Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 64–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, D.; Matsuba, K.M. The development of pride and moral life. In The Self-Conscious Emotions; Tracy, J.L., Robins, R.W., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.W.; Kim, S. National Pride in Comparative Perspective: 1995/96 and 2003/04. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2006, 18, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costello, T.H.; Unterberger, A.; Watts, A.L.; Lilienfeld, S.O. Psychopathy and Pride: Testing Lykken’s Hypothesis Regarding the Implications of Fearlessness for Prosocial and Antisocial Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lenartowicz, T. Measuring Hofstede’s Five Dimensions of Cultural Values at the Individual Level: Development and Validation of CVSCALE. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2011, 23, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Social Survey Programme. ISSP 2013—“National Identity III”. Available online: https://www.gesis.org/en/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/national-identity/2013 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Sinkkonen, E. Nationalism, Patriotism and Foreign Policy Attitudes among Chinese University Students. China Q. 2013, 216, 1045–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, L.; Kasting, M.L.; Head, K.J.; Hartsock, J.A.; Zimet, G.D. Influenza vaccination in the time of COVID-19: A national U.S. survey of adults. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1921–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, S.; Boone, C.; Declerck, C. Social value orientation and cooperation in social dilemmas: A review and conceptual model. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wally, C.M.; Cameron, L.D. A Randomized-Controlled Trial of Social Norm Interventions to Increase Physical Activity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.M.; Ursell, A.; Robinson, E.L.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A.; Herman, C.P.; Higgs, S. Using a descriptive social norm to increase vegetable selection in workplace restaurant settings. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfman, A.; Eyal, T.; Bereby-Meyer, Y. Proud to cooperate: The consideration of pride promotes cooperation in a social dilemma. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 55, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Identity A Read. 1979, 4, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background Factors | n/Mean | %/SD |

|---|---|---|

| Studied province | 2597 | 37.5 |

| Inner Mongolia | 1943 | 28.1 |

| Henan | 931 | 13.4 |

| Zhejiang | 896 | 12.9 |

| Yunnan | 555 | 8.0 |

| Guangdong | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 4402 | 63.6 |

| Male | 2520 | 36.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Else | 913 | 13.2 |

| Han | 6009 | 86.8 |

| Major | ||

| Art; Social science; Economics and management | 1637 | 23.6 |

| Science; Engineering | 1522 | 22.0 |

| Medicine | 3525 | 50.9 |

| Others | 238 | 3.4 |

| Grade | ||

| First year | 2993 | 43.2 |

| Second year | 1894 | 27.4 |

| Third year | 1164 | 16.8 |

| Fourth/fifth year | 776 | 11.2 |

| Postgraduate | 95 | 1.4 |

| Perceived risk | ||

| Low-to-moderate | 6298 | 91.0 |

| High | 624 | 9.0 |

| Behavioral Intention of COVID-19 Vaccination | ||

| 80% efficacy + common mild side effects + free | ||

| Definitely/likely not | 4341 | 62.7 |

| Likely/definitely yes | 2581 | 37.3 |

| 50% efficacy + common mild side effects + free | ||

| Definitely/likely not | 5551 | 80.2 |

| Likely/definitely yes | 1371 | 19.8 |

| Background Factors | Behavioral Intention of Receiving Free COVID-19 Vaccination with Mild Side Effects | |

|---|---|---|

| 80% Efficacy | 50% Efficacy | |

| ORc (95% CI) | ORc (95% CI) | |

| Studied province | ||

| Guangdong | Ref = 1.0 | Ref = 1.0 |

| Inner Mongolia | 1.48 (1.21–1.80) *** | 1.93 (1.50–2.49) *** |

| Henan | 1.16 (0.95–1.43) | 1.10 (0.84–1.44) |

| Zhejiang | 1.18 (0.95–1.48) | 1.27 (0.95–1.70) |

| Yunnan | 1.66 (1.33–2.08) *** | 1.73 (1.30–2.30) *** |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Ref = 1.0 | Ref = 1.0 |

| Male | 1.31 (1.18–1.45) *** | 1.36 (1.21–1.53) *** |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Han | Ref = 1.0 | Ref = 1.0 |

| Else | 1.31 (1.13–1.50) *** | 1.30 (1.10–1.54) ** |

| Faculty | ||

| Art; Social science; Economics and management | Ref = 1.0 | Ref = 1.0 |

| Science; Engineering | 1.05 (0.91–1.22) | 0.96 (0.80–1.15) |

| Medicine | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) * | 1.24 (1.06–1.43) ** |

| Others | 1.01 (0.76–1.34) | 1.08 (0.76–1.52) |

| Grade | ||

| Postgraduate | Ref = 1.0 | Ref = 1.0 |

| Fourth/fifth year | 0.84 (0.54–1.31) | 0.97 (0.55–1.71) |

| Third year | 0.93 (0.61–1.44) | 1.09 (0.62–1.90) |

| Second year | 0.98 (0.64–1.50) | 1.28 (0.74–2.22) |

| First year | 1.02 (0.67–1.56) | 1.31 (0.76–2.26) |

| Perceived risk | ||

| Low-to-moderate | Ref = 1.0 | Ref = 1.0 |

| High | 2.52 (2.13–2.98) *** | 3.21 (2.70–3.81) *** |

| Behavioral Intention of Receiving Free COVID-19 Vaccination with Common Mild Side Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80% Efficacy | 50% Efficacy | |||

| ORc (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | ORc (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | |

| Perceived personal benefits | 1.42(1.34–1.49) *** | 1.36(1.29–1.43) *** | 1.45(1.36–1.54) *** | 1.35(1.27–1.44) *** |

| Perceived social benefits | 1.47(1.39–1.55) *** | 1.44(1.36–1.52) *** | 1.33(1.25–1.41) *** | 1.27(1.19–1.35) *** |

| Collectivism | 1.31(1.25–1.38) *** | 1.27(1.20–1.33) *** | 1.32(1.25–1.41) *** | 1.25(1.18–1.33) *** |

| National pride | 1.17(1.11–1.23) *** | 1.15(1.09–1.21) *** | 1.12(1.05–1.19) *** | 1.09(1.02–1.16) ** |

| Behavioral Intention of Free COVID-19 Vaccination with Frequent Mild Side Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80% Efficacy | 50% Efficacy | |||

| ORa (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | |

| Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 2a | Model 2b | |

| Perceived personal benefits | 1.12 (1.05–1.20) ** | 1.13 (1.05–1.21) *** | 1.30 (1.20–1.42) *** | 1.29 (1.18–1.41) *** |

| Perceived social benefits | 1.33 (1.24–1.43) *** | 1.33 (1.24–1.43) *** | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) |

| Perceived personal benefits × perceived social benefits | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | ||

| Model 1c | Model 1d | Model 2c | Model 2d | |

| Perceived personal benefits | 1.31 (1.24–1.38) *** | 1.31 (1.24–1.38) *** | 1.30 (1.22–1.39) *** | 1.29 (1.21–1.38) *** |

| Collectivism | 1.20 (1.14–1.27) *** | 1.21 (1.14–1.27) *** | 1.19 (1.12–1.26) *** | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) *** |

| Perceived personal benefits × collectivism | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | ||

| Model 1e | Model 1f | Model 2e | Model 2f | |

| Perceived personal benefits | 1.34 (1.27–1.42) *** | 1.35 (1.28–1.42) *** | 1.34 (1.25–1.42) *** | 1.34 (1.26–1.43) *** |

| National pride | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) ** | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) ** | 1.03 (0.96–1.09) | 1.03 (0.96–1.09) |

| Perceived personal benefits × national pride | 0.95 (0.91–1.00) * | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mo, P.K.H.; Yu, Y.; Luo, S.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Lau, J.T.F. Dualistic Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among University Students in China: From Perceived Personal Benefits to External Reasons of Perceived Social Benefits, Collectivism, and National Pride. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111323

Mo PKH, Yu Y, Luo S, Wang S, Zhao J, Zhang G, Li L, Li L, Lau JTF. Dualistic Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among University Students in China: From Perceived Personal Benefits to External Reasons of Perceived Social Benefits, Collectivism, and National Pride. Vaccines. 2021; 9(11):1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111323

Chicago/Turabian StyleMo, Phoenix K. H., Yanqiu Yu, Sitong Luo, Suhua Wang, Junfeng Zhao, Guohua Zhang, Lijuan Li, Liping Li, and Joseph T. F. Lau. 2021. "Dualistic Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among University Students in China: From Perceived Personal Benefits to External Reasons of Perceived Social Benefits, Collectivism, and National Pride" Vaccines 9, no. 11: 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111323

APA StyleMo, P. K. H., Yu, Y., Luo, S., Wang, S., Zhao, J., Zhang, G., Li, L., Li, L., & Lau, J. T. F. (2021). Dualistic Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intention among University Students in China: From Perceived Personal Benefits to External Reasons of Perceived Social Benefits, Collectivism, and National Pride. Vaccines, 9(11), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111323