HPV Exposure in the Gynecological Practice: Time to Call It an Occupational Disease? A Systematic Review of the Literature and ESGO Experts’ Opinion

Abstract

1. Introduction

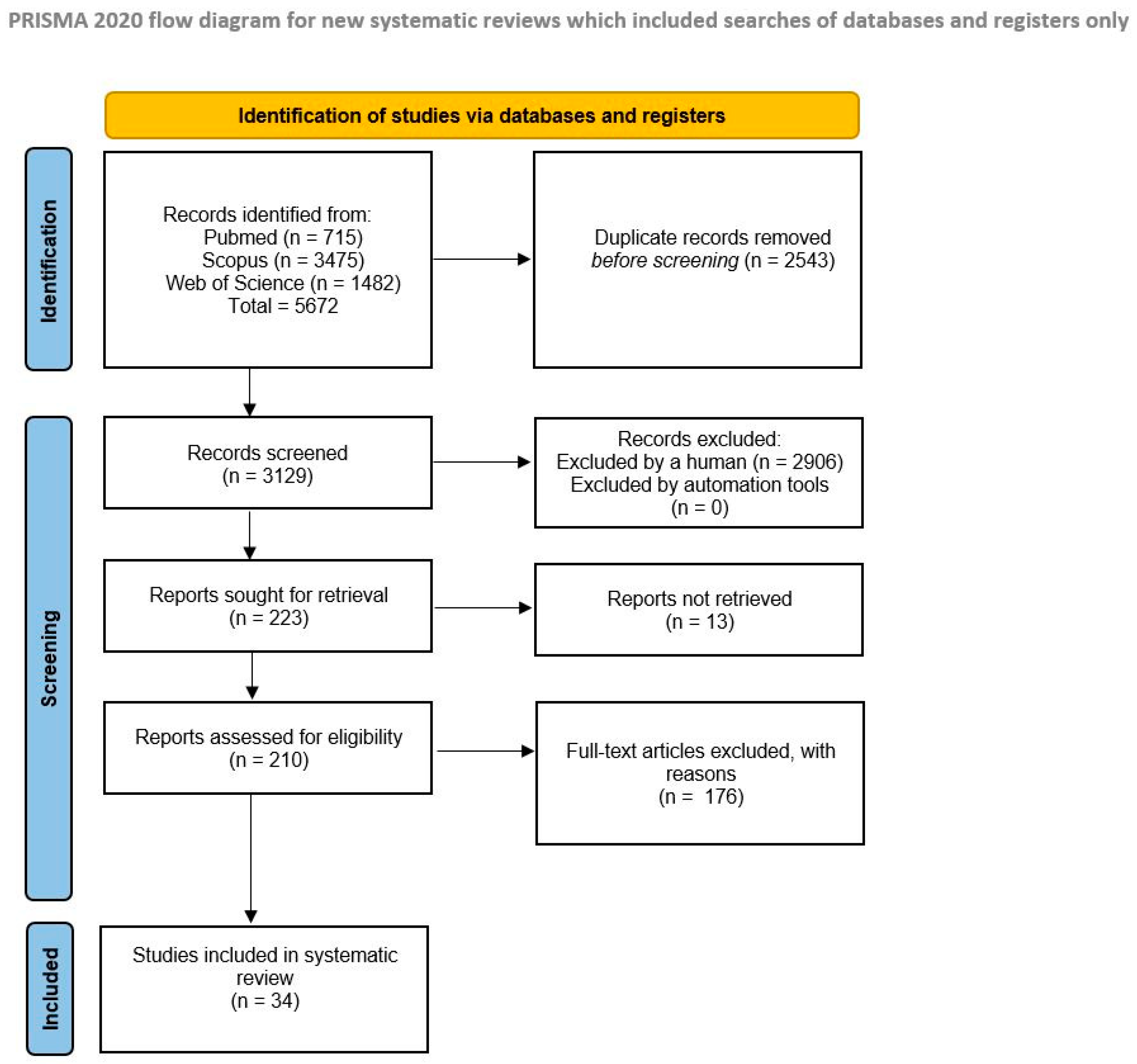

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of HPV Vaccines

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESGO | European Society of Gynaecological Oncology |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| US | United States |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| OPSCCs | Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CIN | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia |

| LEEP | Loop electrosurgical excision procedure |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| HSIL | High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion |

| SCC | Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| ASCCP | American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology |

| BPV | Bovine papillomaviruses |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Roman, B.R.; Aragones, A. Epidemiology and incidence of HPV-related cancers of the head and neck. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 124, 920–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebre, R.; Berry-Lawhorn, J.M.; D’Souza, G. State of the Science: Screening, Surveillance, and Epidemiology of HPV-Related Malignancies. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2021, 41, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Laurent, J.; Luckett, R.; Feldman, S. HPV vaccination and the effects on rates of HPV-related cancers. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2018, 42, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: Epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, R.; Castellsagué, X.; Pawlita, M.; Lissowska, J.; Kee, F.; Balaram, P.; Rajkumar, T.; Sridhar, H.; Rose, B.; Pintos, J.; et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: The International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1772–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, S.; Gnambs, T.; Crevenna, R.; Jordakieva, G. Airborne human papillomavirus (HPV) transmission risk during ablation procedures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, J.M.; O’Banion, M.K.; Shelnitz, L.S.; Pinski, K.S.; Bakus, A.D.; Reichmann, M.E.; Sundberg, J.P. Papillomavirus in the vapor of carbon dioxide laser-treated verrucae. JAMA 1988, 259, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawchuk, W.S.; Weber, P.J.; Lowy, D.R.; Dzubow, L.M. Infectious papillomavirus in the vapor of warts treated with carbon dioxide laser or electrocoagulation: Detection and protection. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1989, 21, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferenczy, A.; Bergeron, C.; Richart, R.M. Human papillomavirus DNA in CO2 laser-generated plume of smoke and its consequences to the surgeon. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 75, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniewski, P.; Warhol, M.; Rando, R.; Sedlacek, T.; Kemp, J.; Fisher, J. Studies on the transmission of viral disease via the CO2 laser plume and ejecta. J. Reprod. Med. 1990, 35, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abramson, A.L.; DiLorenzo, T.P.; Steinberg, B.M. Is papillomavirus detectable in the plume of laser-treated laryngeal papilloma? Arch. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 1990, 116, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, H.K.; Kessis, T.; Mounts, P.; Shah, K. Polymerase chain reaction identification of human papillomavirus DNA in CO2 laser plume from recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 1991, 104, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergbrant, I.M.; Samuelsson, L.; Olofsson, S.; Jonassen, F.; Ricksten, A. Polymerase chain reaction for monitoring human papillomavirus contamination of medical personnel during treatment of genital warts with CO2 laser and electrocoagulation. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 1994, 74, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.K.; Bahrani-Mostafavi, Z.; Stoerker, J.; Stone, I.K. Human papillomavirus DNA in LEEP plume. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 14 2, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunachak, S.; Sithisarn, P.; Kulapaditharom, B. Are laryngeal papilloma virus-infected cells viable in the plume derived from a continuous mode carbon dioxide laser, and are they infectious? A preliminary report on one laser mode. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1996, 110, 1031–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.S.; Hughes, A.P. Absence of human papillomavirus DNA in the plume of erbium: YAG laser–treated warts. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1998, 38, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, J.M.; O’Banion, M.K.; Bakus, A.D.; Olson, C. Viral disease transmitted by laser-generated plume (aerosol). Arch. Dermatol 2002, 138, 1303–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyandt, G.H.; Tollmann, F.; Kristen, P.; Weissbrich, B. Low risk of contamination with human papilloma virus during treatment of condylomata acuminata with multilayer argon plasma coagulation and CO2 laser ablation. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011, 303, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilmarinen, T.; Auvinen, E.; Hiltunen-Back, E.; Ranki, A.; Aaltonen, L.M.; Pitkäranta, A. Transmission of human papillomavirus DNA from patient to surgical masks, gloves and oral mucosa of medical personnel during treatment of laryngeal papillomas and genital warts. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 2012, 269, 2367–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarov, I.; Tok, A.; Wieland, U.; Engelmann, U.; Wille, S. 624 HPV-contamination of laser smoke during laser treatment of condylomata acuminata. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2013, 12, e624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.; Cavalar, M.; Rody, A.; Friemert, L.; Beyer, D.A. Is surgical plume developing during routine LEEPs contaminated with high-risk HPV? A pilot series of experiments. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X. Human papillomavirus DNA in surgical smoke during cervical loop electrosurgical excision procedures and its impact on the surgeon. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 3643–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.R.; Esquivel, D.; Mellinger-Pilgrim, R.; Roden, R.B.S.; Pitman, M.J. Infectivity of murine papillomavirus in the surgical byproducts of treated tail warts. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarayan, R.S.; Shew, M.; Enders, J.; Bur, A.M.; Thomas, S.M. Occupational exposure of oropharyngeal human papillomavirus amongst otolaryngologists. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 2366–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Tu, Q.; Zhu, X. Prevalence of HPV infections in surgical smoke exposed gynecologists. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, X. In vivo and in vitro study of the potential hazards of surgical smoke during cervical cancer treatment with an ultrasonic scalpel. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 164, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallay, C.; Miranda, E.; Schaefer, S.; Catarino, R.; Jacot-Guillarmod, M.; Menoud, P.A.; Guerry, F.; Achtari, C.; Sahli, R.; Vassilakos, P.; et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) contamination of gynaecological equipment. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2016, 92, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodhia, S.; Baxter, P.C.; Ye, F.; Pitman, M.J. Investigation of the presence of HPV on KTP laser fibers following KTP laser treatment of papilloma. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 926–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucet, J.C.; Heard, I.; Roueli, A.; Lafourcade, A.; Mandelbrot, L.; Estellat, C.; Dommergues, M.; PREEV Study Group. Transvaginal ultrasound probes are human papillomavirus-free following low-level disinfection: Cross-sectional multicenter survey. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 54, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, M.; Garland, A.; Webster, D.; Reardon, E. HPV positive tonsillar cancer in two laser surgeons: Case reports. J. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2013, 42, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmo, P.; Naess, O. Laryngeal papillomatosis with human papillomavirus DNA contracted by a laser surgeon. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 1991, 248, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, L.; Brusis, T. Laryngeal papillomatosis—First recognition in Germany as an occupational disease in an operating room nurse. Laryngorhinootologie 2003, 82, 790–793. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J.; Clark, J. HPV positive oropharyngeal cancer in two gynaecologists exposed to electrosurgical smoke plume. Obstet. Gynecol. Cases Rev. 2021, 8, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy, M.; Harrington, R.; Laing, M. Risk of HPV infection among dermatologists: Are we prepared? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 38, E24–E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dawsari, N.A.; Hafez, S.M.; Hafez, D.M.; Al-Tawfiq, J. Self-Precautions among Dermatologists Managing HPV-Related Infections: Awareness and Current Practice of Dermatologists Practicing in Saudi Arabia. Skinmed 2021, 19, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Afsar, S.; Hossain, M.; Islam, M.; Simmonds, H.; Stillwell, A.A.; Butler, K.A. Human papillomavirus and occupational exposure: The need for vaccine provision for healthcare providers. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2342622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, A.M.; Allison, M.K. Occupational Exposure to Aerosolized Human Papillomavirus: Assessing and Addressing Perceptions of and Barriers to Vaccination of at-Risk Health Care Workers. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2024, 30, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobraico, R.V.; Schifano, M.J.; Brader, K.R. A retrospective study on the hazards of the carbon dioxide laser plume. J. Laser Appl. 1988, 1, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloster, H.M.; Roenigk, R.K., Jr. Risk of acquiring human papillomavirus from the plume produced by the carbon dioxide laser in the treatment of warts. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1995, 32, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoed, K.; Norrbom, C.; Forslund, O.; Møller, C.; Frøding, L.P.; Pedersen, A.E.; Markauskas, A.; Blomberg, M.; Baumgartner-Nielsen, J.; Madsen, J.; et al. Low prevalence of oral and nasal human papillomavirus in employees performing CO2-laser evaporation of genital warts or loop electrode excision procedure of cervical dysplasia. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2015, 95, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Deibert, D.; Wyatt, G.; Durand-Moreau, Q.; Adisesh, A.; Khunti, K.; Khunti, S.; Smith, S.; Chan, X.H.S.; Ross, L.; et al. Classification of aerosol-generating procedures: A rapid systematic review. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamboo, A.; Lea, J.; Sommer, D.D.; Sowerby, L.; Abdalkhani, A.; Diamond, C.; Ham, J.; Heffernan, A.; Long, M.C.; Phulka, J.; et al. Clinical evidence based review and recommendations of aerosol generating medical procedures in otolaryngology—Head and neck surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2020, 49, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization. List of Occupational Diseases (Revised 2010); International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Petca, A.; Borislavschi, A.; Zvanca, M.E.; Petca, R.C.; Sandru, F.; Dumitrascu, M.C. Non-sexual HPV transmission and role of vaccination for a better future (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayargoli, P.; Niyibizi, J.; Mayrand, M.H.; Audibert, F.; Monnier, P.; Brassard, P.; Laporte, L.; Lacaille, J.; Zahreddine, M.; Bédard, M.-J.; et al. Human Papillomavirus Transmission and Persistence in Pregnant Women and Neonates. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryndock, E.J.; Meyers, C. A risk for non-sexual transmission of human papillomavirus? Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2014, 12, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Huh, W. Occupational Exposure to Human Papillomavirus and Vaccination for Health Care Workers. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, X.; Curran, A.; Campins, M.; Alemany, L.; Rodrigo-Pendás, J.Á.; Borruel, N.; Castellsagué, X.; Díaz-De-Heredia, C.; Moraga-Llop, F.A.; del Pino, M.; et al. Multidisciplinary, evidence-based consensus guidelines for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in high-risk populations, Spain, 2016. Euro Surveill. 2019, 24, 1700857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Martel, C.; Plummer, M.; Vignat, J.; Franceschi, S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavonen, J.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; Wheeler, C.M.; Chow, S.N.; Apter, D.; Kitchener, H.; Castellsague, X.; Teixeira, J.C.; Skinner, S.R.; et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): Final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet 2009, 374, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiller, J.T.; Castellsagué, X.; Garland, S.M. A review of clinical trials of human papillomavirus prophylactic vaccines. Vaccine 2012, 30, F123–F138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, S.M.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; Wheeler, C.M.; Perez, G.; Harper, D.M.; Leodolter, S.; Tang, G.W.; Ferris, D.G.; Steben, M.; Bryan, J.; et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1928–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macilwraith, P.; Malsem, E.; Dushyanthen, S. The effectiveness of HPV vaccination on the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers in men: A review. Infect. Agents Cancer 2023, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K.J.; Jakobsen, K.K.; Jensen, J.S.; Grønhøj, C.; Von Buchwald, C. The Effect of Prophylactic HPV Vaccines on Oral and Oropharyngeal HPV Infection-A Systematic Review. Viruses 2021, 13, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takes, R.P.; Wierzbicka, M.; D’Souza, G.; Jackowska, J.; Silver, C.E.; Rodrigo, J.P.; Dikkers, F.G.; Olsen, K.D.; Rinaldo, A.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; et al. HPV vaccination to prevent oropharyngeal carcinoma: What can be learned from anogenital vaccination programs? Oral Oncol. 2015, 51, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, R.; Quint, W.; Hildesheim, A.; Gonzalez, P.; Struijk, L.; Katki, H.A.; Porras, C.; Schiffman, M.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Solomon, D.; et al. Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP). HPV Vaccination. ASCCP. Available online: https://portal.asccp.org/hpv-vaccination (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dermatologists Warn of Risks to Medics from HPV, COVID, and Other Viruses in Surgical Smoke. 2021. Available online: https://www.bad.org.uk/dermatologists-warn-of-risks-to-medics-from-hpv-covid-and-other-viruses-in-surgical-smoke (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé; World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper (2022 update)–Vaccins contre les papillomavirus humains: Note de synthèse de l’OMS (mise à jour de 2022). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. = Relev. épidémiologique Hebd. 2022, 97, 645–672. [Google Scholar]

- Summary of WHO Position Papers—Immunization of Health Care Workers 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/table-4-summary-of-who-position-papers-immunization-of-health-care-workers (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Moss, C.E. Control of smoke from laser/electric surgical procedures. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 1999, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitano, T.K.L.; Ketch, P.W.; Scarinci, I.C.; Huh, W.K. An Update on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemtob, L.; Asanati, K.; Jayasekera, P. Should healthcare workers with occupational exposure to HPV be vaccinated? Occup. Med. 2023, 73, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, W.M.; Covey, A.E. Risk of Occupational HPV Exposure Among Medical Trainees: A Call for HPV Vaccination. Kans. J. Med. 2023, 64 16, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, E.F.; Markowitz, L.E.; Taylor, L.D.; Unger, E.R.; Wheeler, C.M. Human papilloma virions in the laboratory. J. Clin. Virol. 2014, 61, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, J.; Ross, L. Vaccinating Providers for HPV Due to Transmission Risk in Ablative Dermatology Procedures. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2023, 16, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yakşi, N.; Topaktaş, B. Knowledge Beliefs and Barriers of Healthcare Workers about Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and HPV Vaccination. Acıbadem Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2023, 14, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Lu, X.; Zhou, W.; Huang, W.; Lu, Y. HPV Vaccination Behavior, Vaccine Preference, and Health Beliefs in Chinese Female Health Care Workers: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlShamlan, N.A.; AlOmar, R.S. HPV Vaccine Uptake, Willingness to Receive, and Causes of Vaccine Hesitancy: A National Study Conducted in Saudi Arabia Among Female Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Women’s Health 2024, 16, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakurnia, A.; Salehpoor, F.; Ghafourian, M.; Nashibi, R. Knowledge and attitudes toward HPV, cervical cancer and HPV vaccine among healthcare providers in Ahvaz, Southwest Iran. Infect Agent Cancer 2025, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Kushwaha, P.; Sud, S.S. Awareness and Acceptance of HPV Vaccine Among Healthcare Workers of Rural Haryana: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Neonatal Surg. 2025, 14, 527–531. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C.L.; McLendon, L.; Green, C.L.; Anderson, K.J.; Pierce, J.Y.; Perkins, A.; Beasley, M. HPV and HPV Vaccination Knowledge and Attitudes Among Medical Students in Alabama. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 36, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, É.; Pérez, N.; Brisson, M. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Xu, L.; Simoens, C.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P. Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomaviruses to prevent cervical cancer and its precursors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, Cd009069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamolratanakul, S.; Pitisuttithum, P. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Efficacy and Effectiveness against Cancer. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Year | Participants | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies examining the risk of HPV transmission to healthcare workers by aerosol route (n = 20) | |||

| Garden JM [7] | 1988 | 7 patients | HPV DNA was studied in smoke from the treatment of papillomavirus-infected warts, and intact HPV DNA was detected in smoke from the treatment of 2/7 (28.5%) cases. |

| Sawchuk WS [8] | 1989 | 8 patients | HPV DNA was studied in smoke from plantar wart treatment. Five of eight laser-derived vapors and four of seven electrocoagulation-derived vapors were positive for human papillomavirus DNA.

|

| Ferenczy A [9] | 1990 | 110 patients and 1 surgeon | No post-procedure HPV DNA has been detected in samples from surgeons treating HPV-containing genital lesions (nasopharynx, eyelids and ears). HPV DNA was detected in 1/5 (20%) prefilter canister.

|

| Wisniewski PM [10] | 1990 | Not available | Airborne viral transmission by laser debris during treatment of HPV-associated lesions is unlikely.

|

| Abramson AL [11] | 1990 | 7 patients | HPV DNA was not detected in surgical smoke when the tip of the aspirator was not in contact with infected tissue. HPV DNA was found in some of the aspiration materials collected by contacting the tissue. |

| Kashima HK [12] | 1991 | 22 patients (19 RRP, 3 non-RRP) | HPV DNA (type 6 or 11) was detected in 17 of 27 smoke samples from 19 patients with recurrent respiratory laryngeal papillomatosis who underwent Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser excision.

|

| Bergbrant IM [13] | 1994 | 79 samples taken from surgeons | Samples (from the nostrils, nasolabial folds, and conjunctiva) taken by the surgeon treating HPV-related genital lesions with CO2 laser or electrocoagulation were tested. HPV DNA was positive in 7 of the pre-treatment samples and in 15 of the post-treatment samples.

|

| Sood AK [14] | 1994 | 49 patients | HPV DNA was detected in 39% (n: 18) of the smoke samples collected from 49 patients who underwent Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) with a diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

|

| Kunachak S [15] | 1996 | 10 samples | Smoke collected from CO2 laser-irradiated laryngeal papilloma samples was inoculated into cultures. No evidence of viral infection was found in the cultures.

|

| Hughes PSH [16] | 1998 | 5 patients | HPV DNA was not detected in the smoke from warts treated with the Erbium YAG laser (Continuum Biomedical, Dublin, Calif.). All warts were positive for HPV DNA.

|

| Garden JM [17] | 2002 | Animal model | Smoke (containing papillomavirus DNA) collected by laser exposure of cutaneous fibropapillomas was inoculated into calf skins. Tumor development at the inoculation sites supported that smoke exposure could cause disease.

|

| Weyandt GH [18] | 2011 | 20 samples | During treatment of HPV-associated lesions with argon plasma coagulation (APC), HPV DNA was detected in samples taken from the surgeon’s eyeglasses and nasolabial fold swabs in a subgroup that differed from samples taken from patients.

|

| Ilmarinen T [19] | 2012 | 18 Healthcare Workers (120 samples) | The transmission of HPV to healthcare workers during the treatment of laryngeal papillomas and urethral warts was investigated. While HPV DNA was detected in gloves (genital wart group 10/10 and RRP group 4/10), HPV DNA was not detected in oral mucosa or surgical mask swabs.

|

| Akbarov I [20] | 2013 | 66 patients | HPV DNA was investigated in the smoke obtained in the treatment of genital warts using YAG-Laser. HPV DNA was detected in all 66 cases. |

| Neumann K [21] | 2018 | 24 patients | HPV DNA (same subtype as the subtype detected in the excision material) was detected in 4 of the surgical smoke samples collected from 24 patients who underwent LEEP for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL). |

| Zhou Q [22] | 2019 | 31 Healthcare Workers, 134 patients | A significant correlation was observed between the presence of HPV DNA in surgical smoke and HPV infection in cervical cells. Analysis of nasal swab samples collected from 31 gynaecologists performing LEEP procedures revealed consistency in the distribution of HPV subtypes in two operators, as detected in corresponding cervical cell and surgical smoke samples. Those operators with positive nasal swabs for HPV 16 or 58 were determined, through regular examinations conducted every 3 months over the subsequent 35 and 43 months, to be free from HPV-related diseases such as warts. Additionally, it is noteworthy that LEEP operators with detected HR-HPV in nasal swabs were found to wear ordinary masks, potentially indicating lower efficacy in preventing viral infections compared to N95 masks. |

| Best SR [23] | 2020 | Animal model | Healthy mice were exposed to smoke samples or contaminated instruments used during treatment of mice with papillomavirus-associated lesions. All mice developed warts.

|

| Subbarayan RS [24] | 2020 | Animal model and 3 patients | HPV DNA was not detected in the surgical smoke generated by the cauterization of a mouse tail injected with plasmid DNA expressing HPV p16, E6, and E7 genes. Similarly, no HPV DNA was detected in surgical smoke, suction tubing, the surgeon’s mask, or the robotic arm during robotic surgery for oropharyngeal cancer.

|

| Hu X [25] | 2021 | 700 Healthcare Workers | HPV DNA was analyzed in nasal swab samples from physicians treating HPV-related lesions, with 67% in the electrosurgery group and 33% in the non-electrosurgery group. HPV DNA detection was significantly higher in the electrosurgery group compared to the non-electrosurgery group (8.96% vs. 1.73%; p < 0.001). The incidence of HPV was lower among those who wore surgical masks during procedures (7.64% vs. 19.15%). Notably, no HPV DNA was detected in individuals using N95 masks, whereas HPV positivity was significantly higher among those using standard surgical masks (0% vs. 13.98%; p < 0.001). The use of smoke-absorbing devices did not significantly reduce HPV incidence. No cases of HPV-related malignancies or diseases were identified in the study cohort. |

| Yan L [26] | 2022 | 18 patients | HPV DNA was detected in 83% (n = 15) of cases in the surgical smoke generated by ultrasonic scalpel use during cervical cancer surgery.

|

| Studies examining the risk of HPV transmission to healthcare workers via the non-aerosol route (n = 3) | |||

| Gallay C [27] | 2016 | 179 samples from equipment | Samples collected from gynecological examination areas, including glove boxes, gynecological chairs, lamps, ultrasound gel tubes, colposcopes, and speculums, revealed an overall HPV positivity rate of 18%. Colposcopes had the highest contamination rate (OR: 3.02, 95% CI: 0.86–10.57). |

| Dodhia S [28] | 2018 | 12 patients | HPV DNA was investigated in potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser fibres used in the treatment of respiratory papillomatosis. HPV DNA was not detected in any of the KTP laser fibres. |

| Lucet JC [29] | 2019 | 676 TVS procedures | Transvaginal ultrasound probe (TVS) and ultrasound keyboard were investigated for the presence of hrHPV. No hrHPV DNA was found in probe swabs, while 0.3% positivity was found in the keyboard. Despite inadequate compliance with hygiene guidelines, no evidence of hrHPV DNA was found in TVS probes. |

| Case reports with evidence of HPV-associated occupational disease (n: 4) | |||

| Rioux M [30] | 2013 | 2 Healthcare Workers | Patient A, a 53-year-old gynaecologist, developed HPV16-positive tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma after performing more than 3000 laser ablations and LEEPs over a period of more than 20 years, with no other risk factors. Patient B, a 62-year-old gynaecologist with a 30-year history of performing similar procedures, developed HPV16-positive base of tongue cancer with minimal other risk factors. These cases suggest that HPV transmission through laser plume may lead to squamous cell carcinoma. |

| Hallmo P [31] | 1991 | 1 Healthcare Worker | The surgeon who performed anogenital condyloma treatment was diagnosed with laryngeal papillomatosis. The detection of HPV 6 and 11 in the lesion was interpreted as a result of inhaled virus particles present in the laser plume. |

| Calero L [32] | 2003 | 1 Healthcare Worker | A 28-year-old gynaecological operating theatre nurse was diagnosed with laryngeal papillomatosis, which had been found several times during the treatment of anogenital condylomas. This clinical condition was associated with occupational exposure. |

| Parker J [33] | 2021 | 2 Healthcare Workers | Patient 1, a gynecologist with remote minimal smoking history and a 31-year monogamous relationship, developed SCC after 27 years of treating ~250 HPV-related lesions without mask or smoke evacuation. Patient 2, a 66-year-old gynecologist, lifelong nonsmoker in a 40-year monogamous relationship, developed SCC after treating ~500 lesions over 40 years, using only a surgical mask.

|

| Opinions of healthcare workers about occupational exposure in the treatment of HPV-associated lesions (n: 4) | |||

| Leahy M [34] | 2023 | 75 Healthcare Workers | In Ireland, a survey among healthcare professionals, including dermatologists, dermatology trainees, nurses and general practitioners who encounter and treat HPV-related lesions, revealed that only 36.8% of respondents were cognizant of the risk of contracting HPV infection through procedures emitting aerosols/smoke, such as cryotherapy, electrocautery, and CO2 lasers. However, 76.8% expressed concerns regarding the occupational transmission of HPV. |

| Al-Dawsari NA [35] | 2021 | 228 Healthcare Workers | Among the study participants, 34.6% were found to be infected with HPV, and during the dermatological practice, 55.7% of these individuals manifested the development of warts. |

| Afsar S [36] | 2024 | 349 Healthcare Workers | Among participants (in USA), 84% were aware of occupational HPV exposure and associated risks. Additionally, 90% expressed willingness to receive the HPV vaccine if provided. However, only 30% were aware of the ASCCP recommendation regarding HPV vaccination for healthcare personnel involved in HPV-related treatments. |

| Mercier AM [37] | 2024 | 37 Healthcare Workers | One-third of HPV vaccinations administered during adulthood have been reported to be motivated by concerns about occupational HPV exposure. The study concluded that healthcare workers lack sufficient knowledge regarding occupational HPV exposure. |

| Studies comparing health care workers treating HPV-associated lesions with control groups (n: 3) | |||

| Lobraico RV [38] | 1988 | 794 Healthcare Workers | The rate of verrucous lesions was 3.2% (n:26) among healthcare workers who treated verrucous lesions with laser. The highest rate was found in dermatologists of 15.2%. A total of 1.7% of gynaecologists and 1.6% of paediatricians reported having lesions.

|

| Gloster HM Jr [39] | 1995 | 570 Healthcare Workers | Surgeons who used CO2 laser and surgeons who did not use CO2 laser had similar rates of warts (5.4% vs 4.9%; p: 0.56). Nasopharyngeal warts were significantly more common in the laser-used group. There was no significant difference in the use of gloves, standard surgical masks, laser masks, smoke evacuators, eye protection, or full surgical gowns between the wart and non-wart groups. |

| Kofoed K [40] | 2015 | 287 Healthcare Workers | Oral rinses and nasal swabs were collected from dermato-venerology and gynaecology staff. Mucosal HPV positivity was 5.8% in the experienced laser treatment of the genital warts group and 1.7% in the inexperienced group (p: 0.12). It was reported that the prevalence of HPV did not increase significantly among healthcare workers who performed treatments for genital warts or cervical dysplasia. |

| Risk Source/Procedure | Recommended Protective Measure |

|---|---|

| Surgical smoke (electrocautery, laser, LEEP) | Smoke evacuation systems, N95/FFP2 masks |

| Aerosol-generating procedures | Adequate ventilation, PPE |

| Contaminated instruments/surfaces | High-level disinfection and sterilization |

| Prolonged occupational exposure | HPV vaccination |

| Lack of awareness or knowledge | Education and awareness programs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ege, H.V.; Temiz, B.E.; Grigore, M.; Burney Ellis, L.; Bowden, S.J.; Lopez-Cavanillas, B.; Preti, M.; Zapardiel, I.; Joura, E.; Gültekin, M.; et al. HPV Exposure in the Gynecological Practice: Time to Call It an Occupational Disease? A Systematic Review of the Literature and ESGO Experts’ Opinion. Vaccines 2026, 14, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14020148

Ege HV, Temiz BE, Grigore M, Burney Ellis L, Bowden SJ, Lopez-Cavanillas B, Preti M, Zapardiel I, Joura E, Gültekin M, et al. HPV Exposure in the Gynecological Practice: Time to Call It an Occupational Disease? A Systematic Review of the Literature and ESGO Experts’ Opinion. Vaccines. 2026; 14(2):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14020148

Chicago/Turabian StyleEge, Hasan Volkan, Bilal Esat Temiz, Mihaela Grigore, Laura Burney Ellis, Sarah J. Bowden, Belen Lopez-Cavanillas, Mario Preti, Ignacio Zapardiel, Elmar Joura, Murat Gültekin, and et al. 2026. "HPV Exposure in the Gynecological Practice: Time to Call It an Occupational Disease? A Systematic Review of the Literature and ESGO Experts’ Opinion" Vaccines 14, no. 2: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14020148

APA StyleEge, H. V., Temiz, B. E., Grigore, M., Burney Ellis, L., Bowden, S. J., Lopez-Cavanillas, B., Preti, M., Zapardiel, I., Joura, E., Gültekin, M., & Kyrgiou, M. (2026). HPV Exposure in the Gynecological Practice: Time to Call It an Occupational Disease? A Systematic Review of the Literature and ESGO Experts’ Opinion. Vaccines, 14(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14020148