Potential of Bovine Herpesvirus Vectors for Recombinant Vaccines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genomic Structure and Organization of BoHVs

3. A Comparative Analysis of BoHVs

4. Methodologies to Engineer BoHV-Vectored Vaccines

4.1. Homologous Recombination

4.2. Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs)

4.3. Codon Optimization and Codon De-Optimization

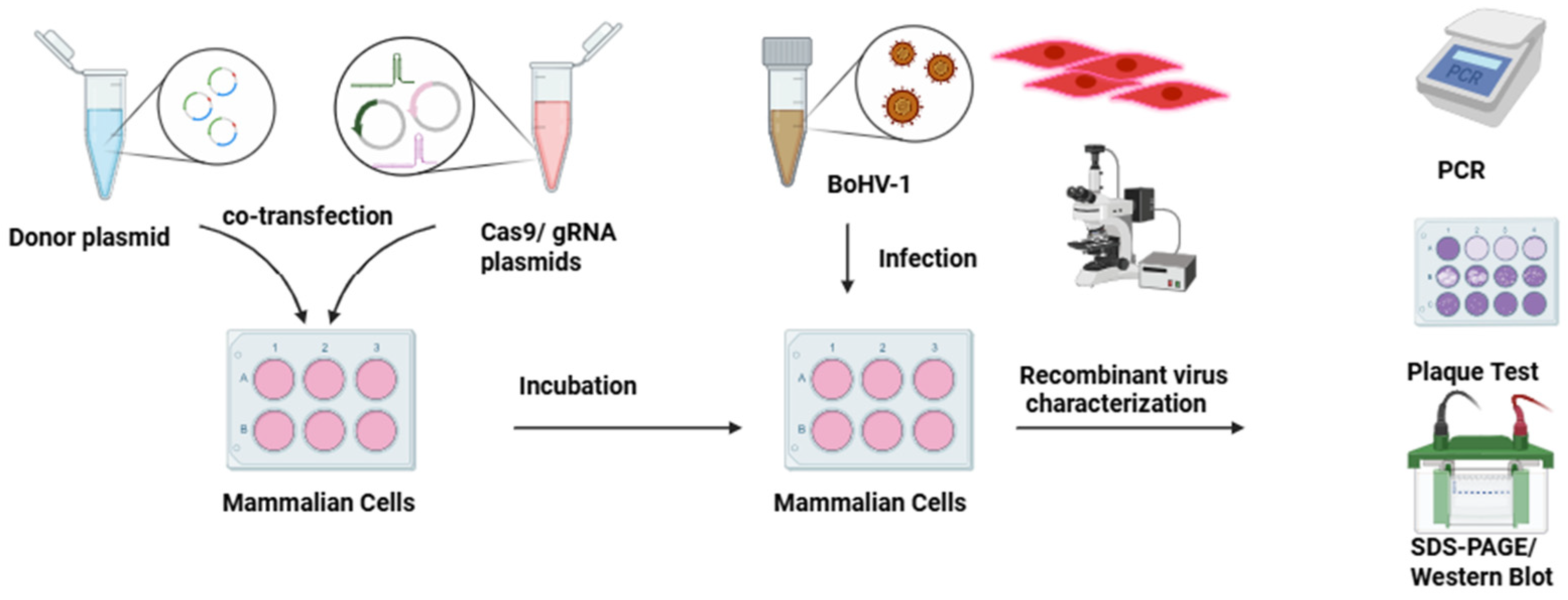

4.4. The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats and CRISPR-Associated Systems (CRISPR-Cas9)

5. Bovine Herpesvirus-Based Platforms for Multivalent and Cross-Species Vaccine Development

5.1. Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus (BRSV)

5.2. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV)

5.3. Foot and Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV)

5.4. Peste Des Petits Ruminants Virus (PPRV)

5.5. Rabies Virus (RABV)

5.6. Rift Valley Fever Virus (RVFV)

5.7. Nipah Virus

5.8. Viral Haemorrhagic Fever Viruses: Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus (CCHFV) and Ebola Virus (EBOV)

5.9. SARS-CoV-2

5.10. Monkeypox Virus (MPXV)

| Vector | Target Disease | Antigen | Vaccine Construction Method | Animal Model | Observed Immune Responses | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BoHV-1 | BRSV | Glycoprotein G (gG) | HR | Calves | Humoral response with high Ab titres | [47] |

| BoHV-1 | BRSV | gG | HR | Calves | Humoral immune response induced partial protection | [73] |

| BoHV-1 | BVDV | Envelope protein E2 | HR | Guinea pigs and calves | Protection with high Ab titres | [48] |

| BoHV-1 | BVDV | Envelope protein E2 | RE-based | Mouse and calves | Humoral immune response with high Ab titres | [49] |

| BoHV-1 | BVDV | Envelope protein E2 | HR | Calves | High neutralising Ab titre | [24] |

| BoHV-1 | BVDV | Envelope protein E2 | CRISPR/Cas9 | Guinea pigs and calves | High neutralising Ab titre | [45] |

| BoHV-1 | FMDV | VP1 epitope | HR | Calves | Protective antibody | [23] |

| BoHV-1 | FMDV | VP1 | HR | Rabbits | Low immune response | [25] |

| BoHV-1 | Rabies virus | gG | CRISPR-Cas9 and HR | Cattle and mice | Strong neutralising antibody | [10] |

| BoHV-1 | RVFV | Glycoproteins Gn and Gc | HR | Calves | High antibody titre | [26] |

| BoHV-1 | RVFV | Glycoproteins Gn and Gc | HR | Sheep | High antibody titres | [56] |

| BoHV-4 | BoHV-1 | gD | BAC | Rabbit | Elicited humoral immune response | [5] |

| BoHV-4 | BoHV-1 | gD | HR | Mice | High humoral immune response | [31] |

| BoHV-4 | BoHV-1 and BVDV | gD (BoHV-1) gE2 (BVDV) | BAC | Rabbit | High humoral immune response | [50] |

| BoHV-4 | BoHV-1 & BVDV | BoHV-1 gD + BVDV gE2 | HR and BAC | Cattle | Antigen-specific neutralising Ab induction | [9] |

| BoHV-4 | PPRV | Hemagglutinin glycoprotein | HR | Mice | High neutralising Ab titres | [53] |

| BoHV-4 | Malignant catarrhal fever virus | Glycoprotein B | BAC | Rabbit | Modest neutralising Ab level, Partial protection (43% survival rate) | [74] |

| BoHV-4 | PPRV | Hemagglutinin glycoprotein | HR | Sheep | Strong protection with high Ab titers | [21] |

| BoHV-4 | CCHFV | Nucleocapsid protein | HR | Mice | Strong humoral responses | [33] |

| BoHV-4 | Ebola | Glycoprotein | BAC | Goat | Long-lasting immunoglobulins | [65] |

| BoHV-4 | Nipah | Fusion (F) and Glycoprotein (G) genes | BAC | Pig | Higher Ab titres and robust cellular immune response for G, Higher neutralising capacity of Ab for F, | [60] |

| BoHV-5 | BoHV-5 | gE and TK deletions | HR | Rabbit | High (gE), Low (TK) | [75] |

| BoHV-5 | BoHV-1 and BoHV-5 | gE and TK deletions | HR | Calves | Strong virus-neutralising Ab titre | [76] |

| BoHV-5 | BoHV-5 | gE, gI, and US9 deletions | HR | Calves | Strong neutralising Ab | [8] |

6. Key Challenges in Bovine Herpesvirus Vectored Vaccines

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ab | Antibody |

| BAC | Bacterial artificial chromosome |

| BRSV | Bovine respiratory syncytial virus |

| BSL-2 | Biosecurity level 2 |

| BVDV | Bovine viral diarrhea virus |

| CCHFV | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus |

| dpv | Day post-vaccination |

| FMDV | Foot-and-mouth disease virus |

| GMO | Genetically modified organism |

| GMCSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| HR | Homologous recombination |

| IFOMA | In the face of maternal antibody |

| IN | Intranasal |

| IM | Intramuscular |

| LAT | latency-associated transcripts |

| NA | Neutralising antibody |

| PPRV | Peste des petits ruminants virus |

| RE | Restriction enzyme |

| RVFV | Rift Valley fever virus |

| SPF | specific pathogen-free |

| TK | Thymidine kinase |

References

- Warnock, J.N.; Daigre, C.; Al-Rubeai, M. Introduction to viral vectors. Methods Mol. 2011, 737, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnagopal, A.; van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk, S. The biology and development of vaccines for bovine alphaherpesvirus 1. Vet. J. 2024, 306, 106152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, B.; Liu, T.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, S.; et al. Design and construction of a fast synthetic modified vaccinia virus Ankara reverse genetics system for advancing vaccine development. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1572706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.B.; Yu, G.W.; Gao, X.Y.; Huang, J.L.; Qin, L.T.; Ni, H.B.; Lyu, C. Intranasal delivery of plasmids expressing bovine herpesvirus 1 gB/gC/gD proteins by polyethyleneimine magnetic beads activates long-term immune responses in mice. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donofrio, G.; Cavirani, S.; Vanderplasschen, A.; Gillet, L.; Flammini, C.F. Recombinant bovine herpesvirus 4 (BoHV-4) expressing glycoprotein D of BoHV-1 is immunogenic and elicits serum-neutralising antibodies against BoHV-1 in a rabbit model. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2006, 13, 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Whitbeck, J.C.; Lawrence, W.C.; Volgin, D.V.; Bello, L.J. Expression of the genomic form of the bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 ORF in a bovine herpesvirus-1 vector. Virus Genes 2003, 27, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahony, T.J. Understanding the molecular basis of disease is crucial to improving the design and construction of herpesviral vectors for veterinary vaccines. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5897–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.S.; Dezen, D.; Antunes, D.A.; Santos, H.F.; Arantes, T.S.; Cenci, A.; Gomes, F.; Lima, F.E.; Brito, W.M.; Filho, H.C.; et al. Efficacy of an inactivated, recombinant bovine herpesvirus type 5 (BoHV-5) vaccine. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 148, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.B.A.; Fry, L.M.; Herndon, D.R.; Franceschi, V.; Schneider, D.A.; Donofrio, G.; Knowles, D.P. A recombinant bovine herpesvirus-4 vectored vaccine delivered via intranasal nebulization elicits viral neutralising antibody titers in cattle. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Ji, L.; Qin, H.; Hu, W.; Yang, Y. A Novel Rabies Vaccine Based on a Recombinant Bovine Herpes Virus Type 1 Expressing Rabies Virus Glycoprotein. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 931043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.H.; Li, Z.M.; Yu, X.J.; Li, D. Alphaherpesvirus in Pets and Livestock. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, L.; Capra, E.; Franceschi, V.; Cavazzini, D.; Sala, R.; Lazzari, B.; Cavirani, S.; Donofrio, G. Characterization of BoHV-4 ORF45. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1171770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, M.; El-Sayed, A. Utilization of herpesviridae as recombinant viral vectors in vaccine development against animal pathogens. Virus Res. 2019, 270, 197648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchers, K.; Goltz, M.; Ludwig, H. Genome organization of the herpesviruses: Minireview. Acta Vet. Hung. 1994, 42, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini, S.; Iscaro, C.; Righi, C. Antibody Responses to Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) in Passively Immunised Calves. Viruses 2019, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, M.; Giuliani, C.; Wild, P.; Beck, T.M.; Loepfe, E.; Wyler, R. The genome of bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) strains exhibiting a neuropathogenic potential compared to known BHV-1 strains by restriction site mapping and cross-hybridization. Virus Res. 1986, 6, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhon, G.; Moraes, M.P.; Lu, Z.; Afonso, C.L.; Flores, E.F.; Weiblen, R.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. Genome of bovine herpesvirus 5. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10339–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schynts, F.; McVoy, M.A.; Meurens, F.; Detry, B.; Epstein, A.L.; Thiry, E. The structures of bovine herpesvirus 1 virion and concatemeric DNA: Implications for cleavage and packaging of herpesvirus genomes. Virology 2003, 314, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and bovine herpesvirus 1 latency. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldován, N.; Torma, G.; Gulyás, G.; Hornyák, Á.; Zádori, Z.; Jefferson, V.A.; Csabai, Z.; Boldogkői, M.; Tombácz, D.; Meyer, F.; et al. Time-course profiling of bovine alphaherpesvirus 1.1 transcriptome using multiplatform sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, D.; Rojas, J.M.; Macchi, F.; Franceschi, V.; Russo, L.; Sevilla, N.; Donofrío, G.; Martín, V. Immunisation with Bovine Herpesvirus-4-Based Vector Delivering PPRV-H Protein Protects Sheep from PPRV Challenge. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 705539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, A.; Riaz, A.; Yousaf, A.; Khan, I.H.; Ur-Rehman, S.; Moaeen-ud-Din, M.; Shah, M.A. Epidemiological survey of bovine gammaherpesvirus 4 (BoHV-4) infection in cattle and buffalo from Pakistan. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kit, M.; Kit, S.; Little, S.P.; Di Marchi, R.D.; Gale, C. Bovine herpesvirus-1 (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus)-based viral vector which expresses foot-and-mouth disease epitopes. Vaccine 1991, 9, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.I.; Pannhorst, K.; Sangewar, N.; Pavulraj, S.; Wen, X.; Stout, R.W.; Mwangi, W.; Paulsen, D.B. BoHV-1-Vectored BVDV-2 Subunit Vaccine Induces BVDV Cross-Reactive Cellular Immune Responses and Protects against BVDV-2 Challenge. Vaccines 2021, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.G.; Xue, F.; Zhu, Y.M.; Tong, G.Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Feng, J.K.; Shi, H.F.; Gao, Y.R. Construction of a recombinant BoHV-1 expressing the VP1 gene of foot and mouth disease virus and its immunogenicity in a rabbit model. Biotechnol. Lett. 2009, 31, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavulraj, S.; Stout, R.W.; Barras, E.D.; Paulsen, D.B.; Chowdhury, S.I. A Novel Quadruple Gene-Deleted BoHV-1-Vectored RVFV Subunit Vaccine Induces Humoral and Cell-Mediated Immune Response against Rift Valley Fever in Calves. Viruses 2023, 15, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahony, T.J.; McCarthy, F.M.; Gravel, J.L.; West, L.; Young, P.L. Construction and manipulation of an infectious clone of the bovine herpesvirus 1 genome maintained as a bacterial artificial chromosome. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 6660–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Jin, M.; Guo, H.; Zhao, H.Z.; Hou, L.N.; Yang, Y.; Wen, Y.J.; Wang, F.X. Concurrent Gene Insertion, Deletion, and Inversion during the Construction of a Novel Attenuated BoHV-1 Using CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, C.; Tang, Q.; Zhu, H. Herpesvirus BACs: Past, present, and future. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 124595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabev, E.; Fraefel, C.; Ackermann, M.; Tobler, K. Cloning of Bovine herpesvirus type 1 and type 5 as infectious bacterial artificial chromosomes. BMC Res. Notes 2009, 2, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge-Dagalp, S.; Farzani, T.A.; Dogan, F.; Akkutay Yoldar, Z.; Ozkul, A.; Alkan, F.; Donofrio, G. Development of a BoHV-4 viral vector expressing tgD of BoHV-1 and evaluation of its immunogenicity in mouse model. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, V.; Capocefalo, A.; Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Redaelli, M.; Mucignat-Caretta, C.; Mertens, P.; Ortego, J.; Donofrio, G. Immunisation of knock-out α/β interferon receptor mice against lethal bluetongue infection with a BoHV-4-based vector expressing BTV-8 VP2 antigen. Vaccine 2011, 29, 3074–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aligholipour Farzani, T.; Földes, K.; Hanifehnezhad, A.; Yener Ilce, B.; Bilge Dagalp, S.; Amirzadeh Khiabani, N.; Ergünay, K.; Alkan, F.; Karaoglu, T.; Bodur, H.; et al. Bovine Herpesvirus Type 4 (BoHV-4) Vector Delivering Nucleocapsid Protein of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus Induces Comparable Protective Immunity against Lethal Challenge in IFNα/β/γR-/- Mice Models. Viruses 2019, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, V.; Parker, S.; Jacca, S.; Crump, R.W.; Doronin, K.; Hembrador, E.; Pompilio, D.; Tebaldi, G.; Estep, R.D.; Wong, S.W.; et al. BoHV-4-Based Vector Single Heterologous Antigen Delivery Protects STAT1(-/-) Mice from Monkeypoxvirus Lethal Challenge. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvritishvili, A.G.; Leung, K.W.; Tombran-Tink, J. Codon preference optimization increases heterologous PEDF expression. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, T.; Miyamori, A.; Sugimoto, T.; Miyazato, P.; Ebina, H. Codon-deoptimized single-round infectious virus for therapeutic and vaccine applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, P.K.; Armat, M.; Hartley, C.A.; Devlin, J.M. Codon pair bias deoptimization of essential genes in infectious laryngotracheitis virus reduces protein expression. J. Gen. Virol. 2023, 104, 001836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, F.; Atkinson, N.J.; Evans, D.J.; Ryan, M.D.; Simmonds, P. RNA virus attenuation by codon pair deoptimisation is an artefact of increases in CpG/UpA dinucleotide frequencies. eLife 2014, 3, e04531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenke, N.; Trimpert, J.; Merz, S.; Conradie, A.M.; Wyler, E.; Zhang, H.; Hazapis, O.G.; Rausch, S.; Landthaler, M.; Osterrieder, N.; et al. Mechanism of Virus Attenuation by Codon Pair Deoptimization. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschke, K.; Trimpert, J.; Osterrieder, N.; Kunec, D. Attenuation of a very virulent Marek’s disease herpesvirus (MDV) by codon pair bias deoptimization. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, S.J.; Silva, R.F.; Hearn, C.J.; Climans, M.; Dunn, J.R. Attenuation of Marek’s disease virus by codon pair deoptimization of a core gene. Virology 2018, 516, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Yao, Y.; Nair, V.; Luo, J. Latest Advances of Virology Research Using CRISPR/Cas9-Based Gene-Editing Technology and Its Application to Vaccine Development. Viruses 2021, 13, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.Y.; Wu, J.H.; VanDusen, N.J.; Li, Y.F.; Zheng, Y.J. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair for precise gene editing. Mol. Ther. Nucl. Acids 2024, 35, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Wu, J.; Yang, H.; Guo, Y.; Di, H.; Gao, M.; Wang, J. Construction of BoHV-1 UL41 Defective Virus Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System and Analysis of Viral Replication Properties. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 942987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Guo, H.; Zhao, H.Z.; Hou, L.N.; Wen, Y.J.; Wang, F.X. Recombinant Bovine Herpesvirus Type I Expressing the Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus E2 Protein Could Effectively Prevent Infection by Two Viruses. Viruses 2022, 14, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Forlenza, M.; Chen, H. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 for Rapid Genome Editing of Pseudorabies Virus and Bovine Herpesvirus-1. Viruses 2024, 16, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrijver, R.S.; Langedijk, J.P.; Keil, G.M.; Middel, W.G.; Maris-Veldhuis, M.; Van Oirschot, J.T.; Rijsewijk, F.A. Immunisation of cattle with a BoHV1 vector vaccine or a DNA vaccine both coding for the G protein of BRSV. Vaccine 1997, 15, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, C.H.; Kang, S.W.; Choi, E.J.; Kang, Y.B. Bovine herpes virus expressing envelope protein (E2) of bovine viral diarrhea virus as a vaccine candidate. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1999, 61, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; van den Hurk, J.V.; Zheng, C.; Yu, H.; Pontarollo, R.A.; Babiuk, L.A.; van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk, S. Immunisation with plasmid DNA encoding a truncated, secreted form of the bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 protein elicits strong humoral and cellular immune responses. Vaccine 2005, 23, 5252–5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donofrio, G.; Sartori, C.; Franceschi, V.; Capocefalo, A.; Cavirani, S.; Taddei, S.; Flammini, C.F. Double immunisation strategy with a BoHV-4-vectorialized secreted chimeric peptide BVDV-E2/BoHV-1-gD. Vaccine 2008, 26, 6031–6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubman, M.J.; Baxt, B. Foot-and-mouth disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, N.A.; Röder, A.; Giesow, K.; Keil, G.M. Genetic fusion of peste des petits ruminants virus haemagglutinin and fusion protein domains to the amino terminal subunit of glycoprotein B of bovine herpesvirus 1 interferes with transport and function of gB for BHV-1 infectious replication. Virus Res. 2018, 258, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchi, F.; Rojas, J.M.; Verna, A.E.; Sevilla, N.; Franceschi, V.; Tebaldi, G.; Cavirani, S.; Martín, V.; Donofrio, G. Bovine Herpesvirus-4-Based Vector Delivering Peste des Petits Ruminants Virus Hemagglutinin ORF Induces both Neutralising Antibodies and Cytotoxic T Cell Responses. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemachudha, T.; Laothamatas, J.; Rupprecht, C.E. Human rabies: A disease of complex neuropathogenetic mechanisms and diagnostic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2002, 1, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, S.; Lokugamage, N.; Ikegami, T. The L, M, and S Segments of Rift Valley Fever Virus MP-12 Vaccine Independently Contribute to a Temperature-Sensitive Phenotype. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 3735–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavulraj, S.; Stout, R.W.; Chowdhury, S.I. A Novel BoHV-1-Vectored Subunit RVFV Vaccine Induces a Robust Humoral and Cell-Mediated Immune Response Against Rift Valley Fever in Sheep. Viruses 2025, 17, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavulraj, S.; Stout, R.W.; Paulsen, D.B.; Chowdhury, S.I. A Quadruple Gene-Deleted Live BoHV-1 Subunit RVFV Vaccine Vector Reactivates from Latency and Replicates in the TG Neurons of Calves but Is Not Transported to and Shed from Nasal Mucosa. Viruses 2024, 16, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokan, S.; Luke, M.S.; Atiyah, H.M.; Noori, S.S.; Atiyah, M.M.; Makeshkumar, V.; Verma, G.; Jagadeesan, A.; Beniwal, N.; Vijayan, S.; et al. Nipah virus as a pandemic threat: Current knowledge, diagnostic gaps, and future research priorities. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2026, 114, 117141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, M.Z. Structural biology of Nipah virus G and F glycoproteins: Insights into therapeutic and vaccine development. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2025, 15, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrera, M.; Macchi, F.; McLean, R.K.; Franceschi, V.; Thakur, N.; Russo, L.; Medfai, L.; Todd, S.; Tchilian, E.Z.; Audonnet, J.C.; et al. Bovine Herpesvirus-4-Vectored Delivery of Nipah Virus Glycoproteins Enhances T Cell Immunogenicity in Pigs. Vaccines 2020, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengler, J.R.; Bergeron, E.; Rollin, P.E. Seroepidemiological Studies of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus in Domestic and Wild Animals. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, H.A. Brief review on ebola virus disease and one health approach. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Empig, C.J.; Goldsmith, M.A. Association of the caveola vesicular system with cellular entry by filoviruses. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5266–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, G.; Wool-Lewis, R.J.; Baribaud, F.; Netter, R.C.; Bates, P. Ebola virus glycoproteins induce global surface protein down-modulation and loss of cell adherence. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosamilia, A.; Jacca, S.; Tebaldi, G.; Tiberti, S.; Franceschi, V.; Macchi, F.; Cavirani, S.; Kobinger, G.; Knowles, D.P.; Donofrio, G. BoHV-4-based vector delivering Ebola virus surface glycoprotein. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.; Ahmad, M.I. COVID-19: A wreak havoc across the globe. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 129, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tōdō, T. Pharmaceutical Composition Containing Herpes Simplex Virus Vector. WO2024038857A1, 22 February 2024. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2024038857A1/en (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Kim, Y.; Zheng, X.Y.; Eschke, K.; Chaudhry, M.Z.; Bertoglio, F.; Tomic, A.; Krmpotic, A.; Hoffmann, M.; Bar-On, Y.; Boehme, J.; et al. MCMV-based vaccine vectors expressing full-length viral proteins provide long-term humoral immune protection upon a single-shot vaccination. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzdorf, K.; Jacobsen, H.; Kim, Y.; Alves, L.G.T.; Kulkarni, U.; Brdovcak, M.C.; Materljan, J.; Eschke, K.; Chaudhry, M.Z.; Hoffmann, M.; et al. A single-dose MCMV-based vaccine elicits long-lasting immune protection in mice against distinct SARS-CoV-2 variants. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1383086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jaijyan, D.K.; Chen, Y.; Feng, C.; Yang, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhan, N.; Hong, C.; Li, S.; Cheng, T.; et al. Cytomegalovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccines elicit neutralizing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (BA.2) in mice. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0246323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Conti, L.; Franceschi, V.; Oh, B.; Yang, M.S.; Ham, G.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Bolli, E.; Cavallo, F.; Kim, B.; et al. Assessment of BoHV-4-based vector vaccine intranasally administered in a hamster challenge model of lung disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1197649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Chaudhary, A.A.; Srivastava, U.; Gupta, S.; Rustagi, S.; Rudayni, H.A.; Kashyap, V.K.; Kumar, S. Mpox 2022 to 2025 Update: A Comprehensive Review on Its Complications, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Viruses 2025, 17, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.; Rijsewijk, F.A.; Thomas, L.H.; Wyld, S.G.; Gaddum, R.M.; Cook, R.S.; Morrison, W.I.; Hensen, E.; van Oirschot, J.T.; Keil, G.M. Resistance to bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) induced in calves by a recombinant bovine herpesvirus-1 expressing the attachment glycoprotein of BRSV. J. Gen. Virol. 1998, 79, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shringi, S.; O’Toole, D.; Cole, E.; Baker, K.N.; White, S.N.; Donofrio, G.; Li, H.; Cunha, C.W. OvHV-2 Glycoprotein B Delivered by a Recombinant BoHV-4 Is Immunogenic and Induces Partial Protection against Sheep-Associated Malignant Catarrhal Fever in a Rabbit Model. Vaccines 2021, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.C.; Brum, M.C.; Weiblen, R.; Flores, E.F.; Chowdhury, S.I. A bovine herpesvirus 5 recombinant defective in the thymidine kinase (TK) gene and a double mutant lacking TK and the glycoprotein E gene are fully attenuated for rabbits. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2010, 43, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anziliero, D.; Santos, C.M.; Brum, M.C.; Weiblen, R.; Chowdhury, S.I.; Flores, E.F. A recombinant bovine herpesvirus 5 defective in thymidine kinase and glycoprotein E is immunogenic for calves and confers protection upon homologous challenge and BoHV-1 challenge. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 154, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, M. Viral vectors for veterinary vaccines. Adv. Vet. Med. 1999, 41, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Wen, X.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Ni, H. Meta-analysis of prevalence of bovine herpes virus 1 in cattle in Mainland China. Acta Trop. 2018, 187, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windeyer, M.C.; Gamsjäger, L. Vaccinating Calves in the Face of Maternal Antibodies: Challenges and Opportunities. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2019, 35, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, R.W.; Briggs, R.E.; Payton, M.E.; Confer, A.W.; Saliki, J.T.; Ridpath, J.F.; Burge, L.J.; Duff, G.C. Maternally derived humoral immunity to bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) 1a, BVDV1b, BVDV2, bovine herpesvirus-1, parainfluenza-3 virus bovine respiratory syncytial virus, Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida in beef calves, antibody decline by half-life studies and effect on response to vaccination. Vaccine 2004, 22, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzi, A.; Bakhshesh, M.; Hatami, A.; Shoukri, M.R. Study on duration of maternal antibodies in calves against Bovine Herpes virus (BHV-1). Arch. Razi Inst. 2011, 66, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, M.; Weynants, V.; Godfroid, J.; Schynts, F.; Meyer, G.; Letesson, J.J.; Thiry, E. Effects of bovine herpesvirus type 1 infection in calves with maternal antibodies on immune response and virus latency. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, S.; Martucciello, A.; Righi, C.; Cappelli, G.; Costantino, G.; Grassi, C.; Casciari, C.; Scoccia, E.; Tinelli, E.; Galiero, G.; et al. Evaluation of passive immunity from dams previously immunised with an inactivated glycoprotein E-deleted infectious bovine rhinotracheitis marker vaccine after challenge infection with wild-type bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 in calves. Vaccine X 2025, 25, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, S.; Martucciello, A.; Righi, C.; Cappelli, G.; Torresi, C.; Grassi, C.; Scoccia, E.; Costantino, G.; Casciari, C.; Sabato, R.; et al. Assessment of Different Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis Marker Vaccines in Calves. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Fu, S.; Deng, M.; Xie, Q.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Guo, A. Attenuation of bovine herpesvirus type 1 by deletion of its glycoprotein G and tk genes and protection against virulent viral challenge. Vaccine 2011, 29, 8943–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Geiser, V.; Henderson, G.; Jiang, Y.; Meyer, F.; Perez, S.; Zhang, Y. Functional analysis of bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) genes expressed during latency. Vet. Microbiol. 2006, 113, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, D.; Lokensgard, J.; Lewis, T.; Kutish, G. Characterization of dexamethasone-induced reactivation of latent bovine herpesvirus 1. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 2484–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mayet, F.; Jones, C. Stress Can Induce Bovine Alpha-Herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) Reactivation from Latency. Viruses 2024, 16, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomer, G.; Workman, A.; Harrison, K.S.; Stayton, E.; Hoyt, P.R.; Jones, C. Stress Triggers Expression of Bovine Herpesvirus 1 Infected Cell Protein 4 (bICP4) RNA during Early Stages of Reactivation from Latency in Pharyngeal Tonsil. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.; Arsic, N.; Nordstrom, S.; Griebel, P.J. Immune memory induced by intranasal vaccination with a modified-live viral vaccine delivered to colostrum fed neonatal calves. Vaccine 2019, 37, 7455–7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, L.A.; Rele, S.; Hofmeyer, K.A.; Luck, B.B.; Wolfe, D.N. Strategic and Technical Considerations in Manufacturing Viral Vector Vaccines for the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority Threats. Vaccines 2025, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, S.; Jasny, E.; Schmidt, K.E.; Petsch, B. New Vaccine Technologies to Combat Outbreak Situations. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samrath, D.; Shakya, S.; Rawat, N.; Gilhare, V.R.; Singh, F. Isolation and adaptation of bovine herpes virus Type 1 in embryonated chicken eggs and in Madin-Darby bovine kidney cell line. Vet. World 2016, 9, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donofrio, G.; Manarolla, G.; Ravanetti, L.; Sironi, G.; Cavirani, S.; Cabassi, C.S.; Flammini, C.F.; Rampin, T. Assessment of bovine herpesvirus 4 based vector in chicken. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 148, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donofrio, G.; Cavirani, S.; Simone, T.; van Santen, V.L. Potential of bovine herpesvirus 4 as a gene delivery vector. J. Virol. Methods 2002, 101, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Takashima, Y.; Xuan, X.; Otsuka, H. Growth behavior of bovine herpesvirus-1 in permissive and semi-permissive cells. Virus Res. 1999, 61, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, S.; Hao, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Liu, M.; Tian, X.; Ge, L.; Wu, W.; Peng, C. Establishment of a Suspension MDBK Cell Line in Serum-Free Medium for Production of Bovine Alphaherpesvirus-1. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Liu, Q. Cell-Line Serum-Free Suspension Culture Method for Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis Virus. CN111671893B, 19 July 2022. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN111671893B/en (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Sadri, R.; Fallahi, R.; Kamalzadeh, M.; Haghighi, S. Development of a bovine turbinate cell line and its application in isolation of viral antigen and vaccine production for large animal diseases. In Proceedings of the 13th Association of Institutions for Tropical Veterinary Medicine (AITVM) Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, 23–26 August 2010; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderplasschen, A.F.C.; Thirion, M.M.C. Bovine Herpesvirus Vaccine. ZA201201387B, 28 November 2012. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/ZA201201387B/en (accessed on 13 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gokduman, E.M.; Atasoy, M.O.; Goksu, A.G.; Sozdutmaz, İ.; Munir, M. Potential of Bovine Herpesvirus Vectors for Recombinant Vaccines. Vaccines 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010006

Gokduman EM, Atasoy MO, Goksu AG, Sozdutmaz İ, Munir M. Potential of Bovine Herpesvirus Vectors for Recombinant Vaccines. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleGokduman, Eda Mert, Mustafa Ozan Atasoy, Ayşe Gencay Goksu, İbrahim Sozdutmaz, and Muhammad Munir. 2026. "Potential of Bovine Herpesvirus Vectors for Recombinant Vaccines" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010006

APA StyleGokduman, E. M., Atasoy, M. O., Goksu, A. G., Sozdutmaz, İ., & Munir, M. (2026). Potential of Bovine Herpesvirus Vectors for Recombinant Vaccines. Vaccines, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010006