Novel Multistage Subunit Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nanoparticle Vaccine Confers Protection Against Experimental Infection in Prophylactic and Therapeutic Regimens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primers Used for Genes Amplification

2.2. Fusion Protein Expression and Purification

2.3. SDS-Page and Western Blotting Techniques

2.4. High-Resolution LC–MS/MS Analysis of ESAT6-CFP10-Ag85A-Rv2660c-Rv1813c Fusion Protein

2.5. Preparation of Vaccine Nanoparticles

2.6. Characterization of Physical Parameters of Vaccine NPs

2.7. Measurement of Antigen Encapsulated in Vaccine NPs

2.8. Measurement of PRR Agonists Internalized in Vaccine NPs

2.9. Animal Studies

2.10. Sample Acquisition

2.11. Mycobacterium Strains

2.12. Analysis of Lymphoproliferative Response

2.13. Cytokine Analysis

2.14. Serum IgG Titers Measured by Bead-Based Assay

2.15. Serum and BAL Antibody Titers Measured by ELISA

2.16. Quantification of Bacterial Burden

2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of Recombinant Fusion ESAT6-CFP10-Ag85A-Rv2660c-Rv1813c Protein

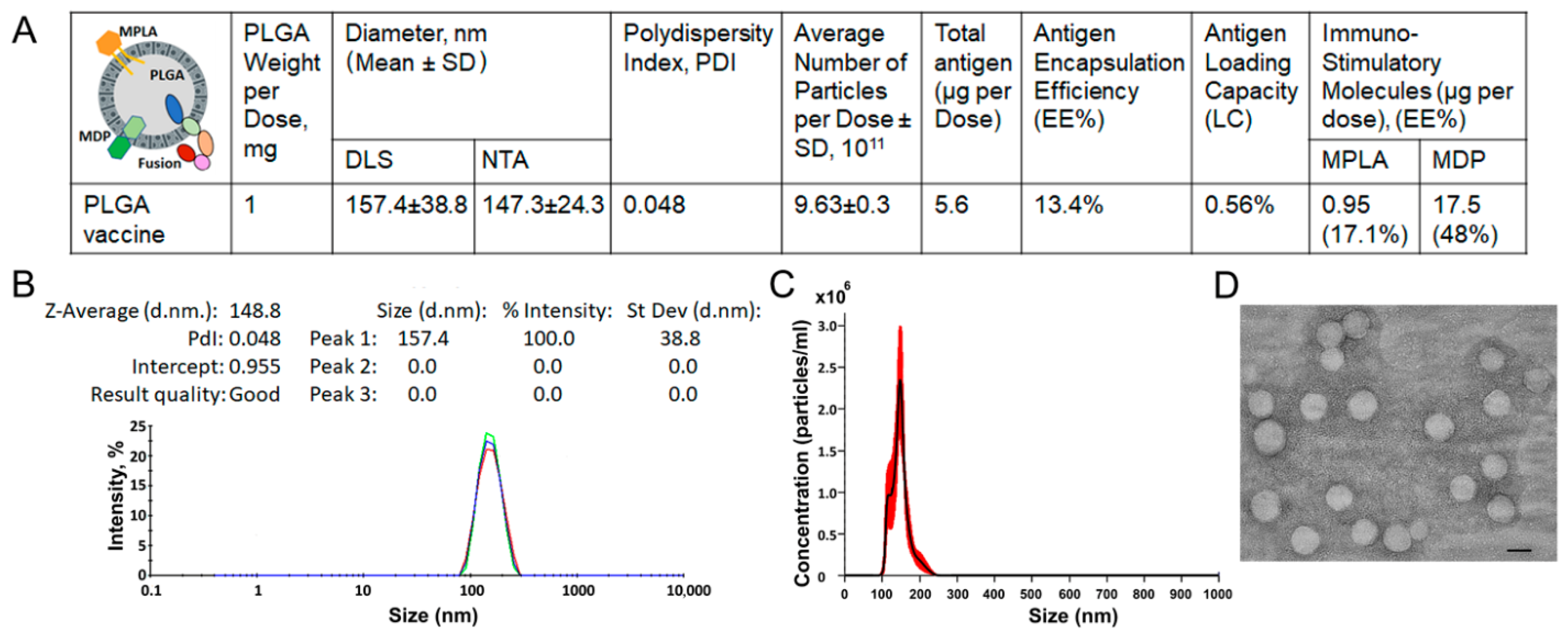

3.2. Preparation and Characterization of PLGA-Based Multistage Vaccine

3.3. A PLGA-Based Multistage Vaccine Elicits a Robust T Cell-Mediated Immune Response Characterized by Th1/Th17 Polarity in Mice

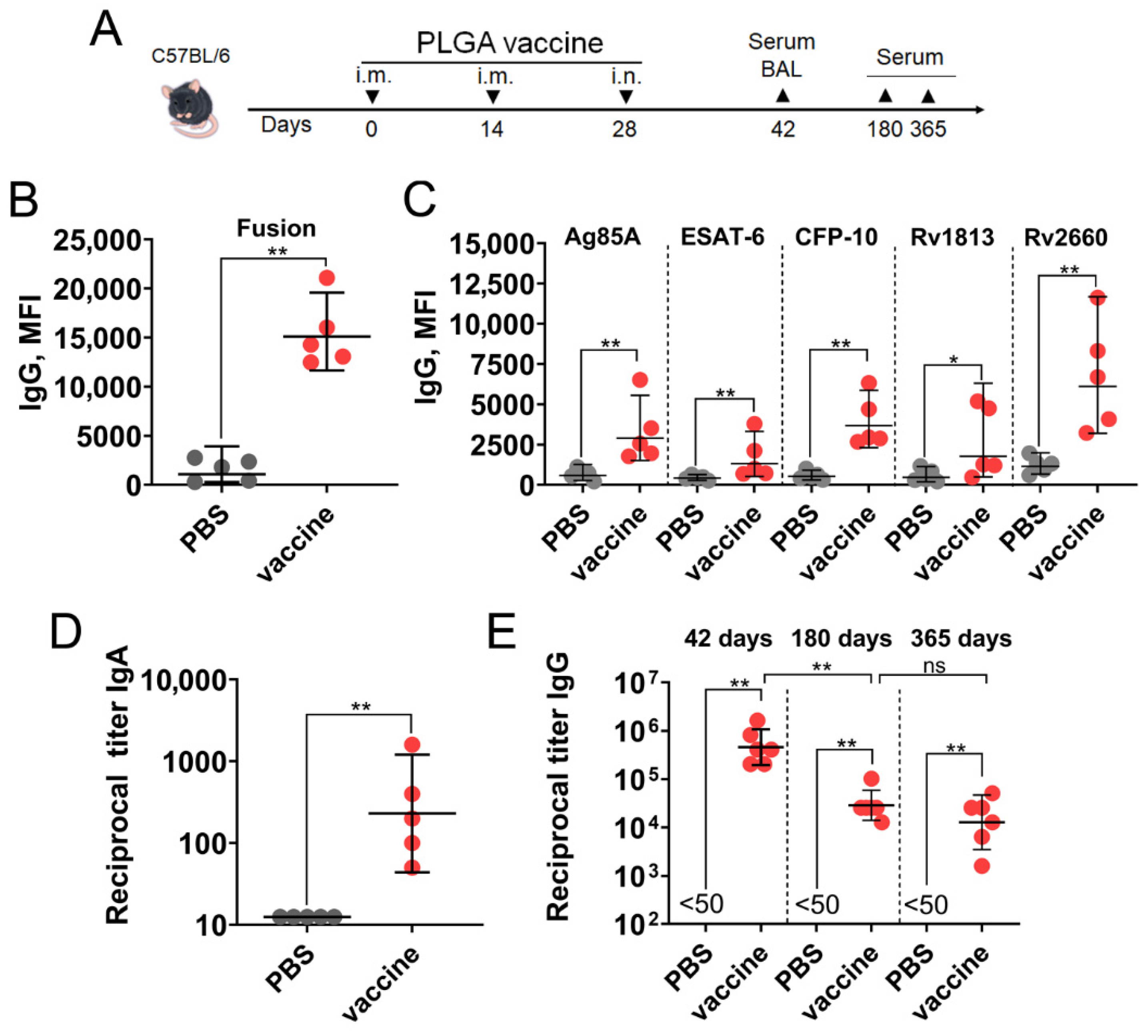

3.4. A PLGA-Based Multistage Vaccine Induces Robust Humoral Immune Response in Mice

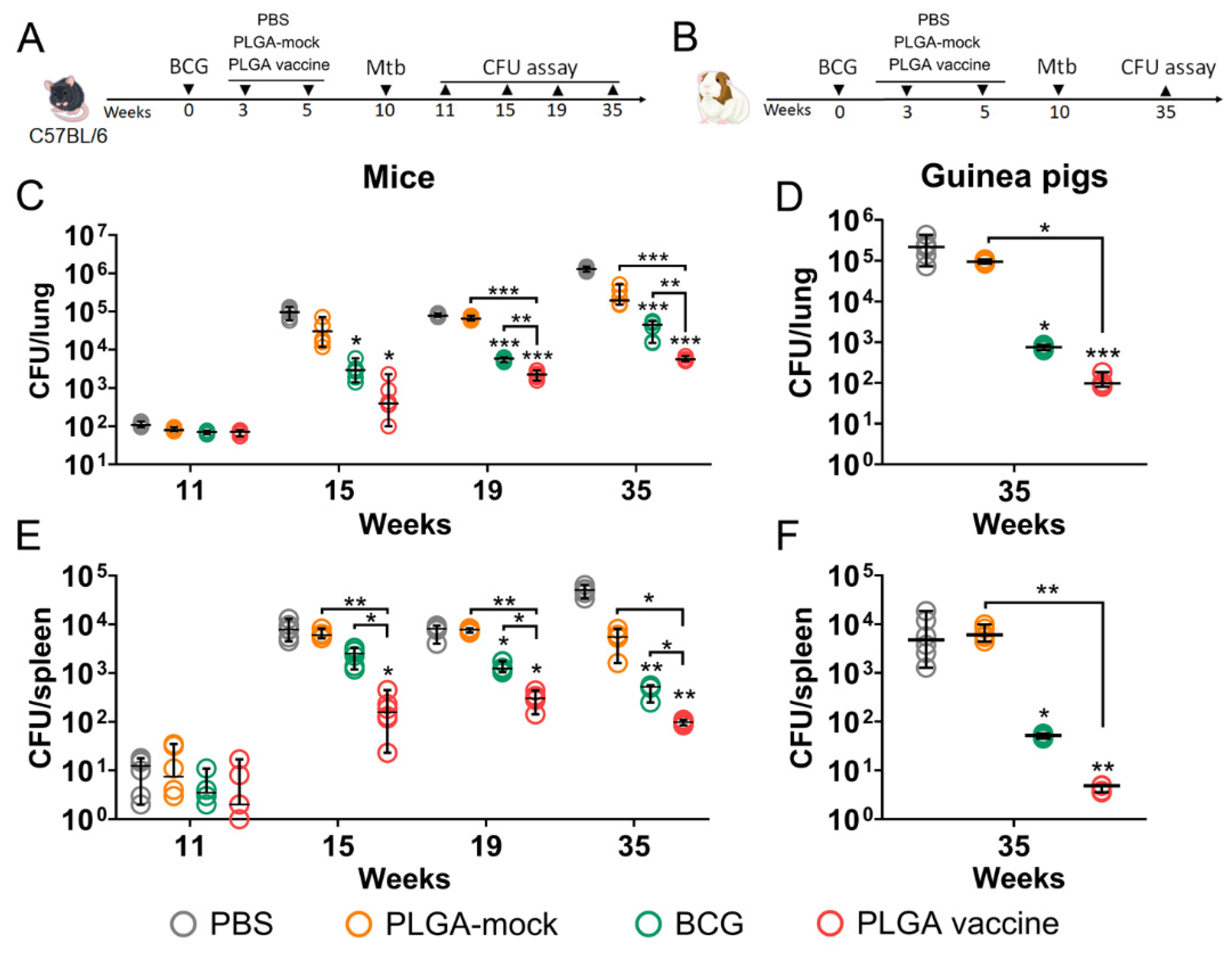

3.5. PLGA-Based Multistage Vaccine Enhances BCG-Mediated Protection in Pre-Exposure Infection Model

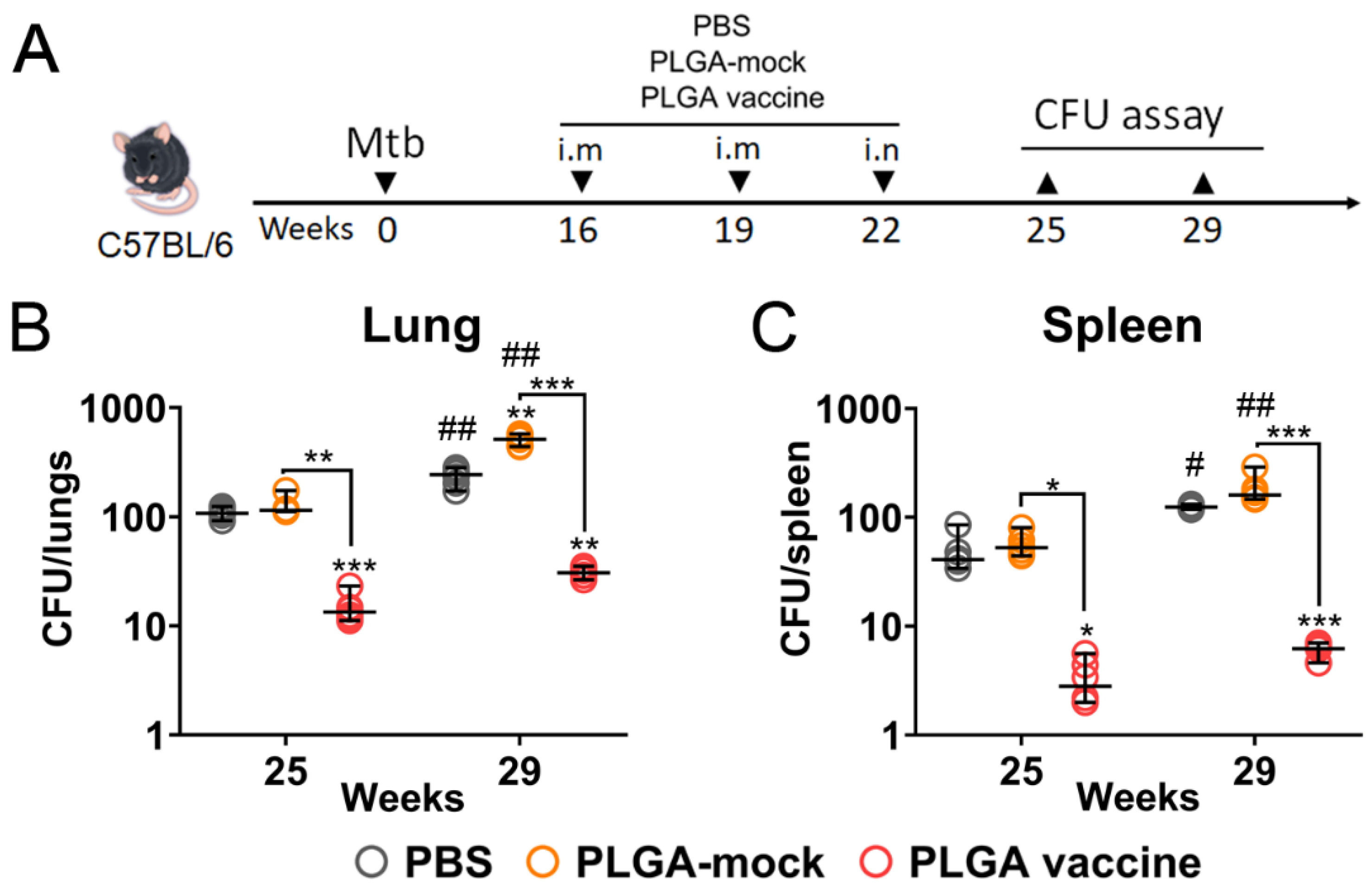

3.6. PLGA-Based Multistage Vaccine Induces Protection in Post-Exposure Infection Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Resurges as Top Infectious Disease Killer; News Release; World Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023/tb-disease-burden/1-3-drug-resistant-tb (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Zhuang, L.; Ye, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Gong, W. Next-Generation TB Vaccines: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, T.; Khatchadourian, C.; Nguyen, H.; Dara, Y.; Jung, S.; Venketaraman, V. A review of the BCG vaccine and other approaches toward tuberculosis eradication. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 2454–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzeyen, R.; Javid, B. Therapeutic Vaccines for Tuberculosis: An Overview. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 878471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velayutham, B. Overview of the tuberculosis vaccine development landscape. Indian. J. Tuberc. 2025, 72, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Basteiro, A.L.; White, R.G.; Tait, D.; Schmidt, A.C.; Rangaka, M.X.; Quaife, M.; Nemes, E.; Mogg, R.; Hill, P.C.; Harris, R.C.; et al. End-point definition and trial design to advance tuberculosis vaccine development. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.E., 3rd; Boshoff, H.I.; Dartois, V.; Dick, T.; Ehrt, S.; Flynn, J.; Schnappinger, D.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Young, D. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: Rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, N.; Pawar, S.; Sirakova, T.D.; Deb, C.; Warren, W.L.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Human granuloma in vitro model, for TB dormancy and resuscitation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salina, E.G.; Makarov, V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Dormancy: How to Fight a Hidden Danger. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, F.; Derakhshan, M.; Yousefi-Avarvand, A.; Tafaghodi, M.; Soleimanpour, S. Multi-stage subunit vaccines against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: An alternative to the BCG vaccine or a BCG-prime boost? Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2018, 17, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.; Rhoades, E.R.; Keen, M.; Belisle, J.T.; Frank, A.A.; Orme, I.M. Effective preexposure tuberculosis vaccines fail to protect when they are given in an immunotherapeutic mode. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 1706–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, A.A.; Stehr, M.; Spallek, R.; Rohde, M.; Singh, M. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ag85A is a novel diacylglycerol acyltransferase involved in lipid body formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 81, 1577–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, M.I.; Pehau-Arnaudet, G.; Fretz, M.M.; Romain, F.; Bottai, D.; Brodin, P.; Honore, N.; Marchal, G.; Jiskoot, W.; England, P.; et al. ESAT-6 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis dissociates from its putative chaperone CFP-10 under acidic conditions and exhibits membrane-lysing activity. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 6028–6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretl, D.J.; He, H.; Demetriadou, C.; White, M.J.; Penoske, R.M.; Salzman, N.H.; Zahrt, T.C. MprA and DosR coregulate a Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence operon encoding Rv1813c and Rv1812c. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 3018–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, J.; Cortes, T.; Schubert, O.; Rose, G.; Rodgers, A.; De Ste Croix, M.; Aebersold, R.; Young, D.B.; Arnvig, K.B. A small RNA encoded in the Rv2660c locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is induced during starvation and infection. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chugh, S.; Bahal, R.K.; Dhiman, R.; Singh, R. Antigen identification strategies and preclinical evaluation models for advancing tuberculosis vaccine development. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, V.; Berthet, M.; Resseguier, J.; Legaz, S.; Handke, N.; Gilbert, S.C.; Paul, S.; Verrier, B. Poly(lactic acid) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) particles as versatile carrier platforms for vaccine delivery. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 2703–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Chen, Y.; Pei, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, L.; Sun, L. The drug release of PLGA-based nanoparticles and their application in treatment of gastrointestinal cancers. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Gupta, M.; Mani, R.; Bhatnagar, R. Single-dose Ag85B-ESAT6-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles confer protective immunity against tuberculosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 3129–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukhvatulin, A.; Dzharullaeva, A.; Erokhova, A.; Zemskaya, A.; Balyasin, M.; Ozharovskaia, T.; Zubkova, O.; Shevlyagina, N.; Zhukhovitsky, V.; Fedyakina, I.; et al. Adjuvantation of an Influenza Hemagglutinin Antigen with TLR4 and NOD2 Agonists Encapsulated in Poly(D,L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles Enhances Immunogenicity and Protection against Lethal Influenza Virus Infection in Mice. Vaccines 2020, 8, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, J.H.A.; Pawlitzky, I.; Grosios, K.; Gileadi, U.; Middleton, M.R.; Gerritsen, W.R.; Mehra, N.; Rivoltini, L.; Walters, I.; Figdor, C.G.; et al. Assessing the safety, tolerability and efficacy of PLGA-based immunomodulatory nanoparticles in patients with advanced NY-ESO-1-positive cancers: A first-in-human phase I open-label dose-escalation study protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, A.P.; Bykonia, E.N.; Popova, L.I.; Kleymenov, D.A.; Semashko, M.A.; Chulanov, V.P.; Fitilev, S.B.; Maksimov, S.L.; Smolyarchuk, E.A.; Manuylov, V.A.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the GamTBvac, the Recombinant Subunit Tuberculosis Vaccine Candidate: A Phase II, Multi-Center, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Vaccines 2020, 8, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luminex xMAP Cookbook 6th Edition. Available online: https://int.diasorin.com/it/luminex/xmap-education/xmap-cookbook (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Mazunina, E.P.; Kleymenov, D.A.; Manuilov, V.A.; Gushchin, V.A.; Tkachuk, A.P. A protocol of development of a screening assay for evaluating immunological memory to vaccine-preventable infections: Simultaneous detection of antibodies to measles, mumps, rubella and hepatitis B. Bull. RSMU 2017, 5, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukhvatulin, A.I.; Dzharullaeva, A.S.; Tukhvatulina, N.M.; Shcheblyakov, D.V.; Shmarov, M.M.; Dolzhikova, I.V.; Stanhope-Baker, P.; Naroditsky, B.S.; Gudkov, A.V.; Logunov, D.Y.; et al. Powerful Complex Immunoadjuvant Based on Synergistic Effect of Combined TLR4 and NOD2 Activation Significantly Enhances Magnitude of Humoral and Cellular Adaptive Immune Responses. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulateefeh, S.R. Long-acting injectable PLGA/PLA depots for leuprolide acetate: Successful translation from bench to clinic. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, A.S.; Abdullah, N.; Ahmadun, F.R. In vitro degradation of poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles loaded with linamarin. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 7, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; McFarland, C.T.; Sallenave, J.M.; Izzo, A.; Wang, J.; McMurray, D.N. Intranasal mucosal boosting with an adenovirus-vectored vaccine markedly enhances the protection of BCG-primed guinea pigs against pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami, S.; D’Agostino, M.R.; Vaseghi-Shanjani, M.; Lepard, M.; Yang, J.X.; Lai, R.; Choi, M.W.Y.; Chacon, A.; Zganiacz, A.; Franken, K.; et al. Intranasal multivalent adenoviral-vectored vaccine protects against replicating and dormant M.tb in conventional and humanized mice. NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Blanc, C.; Eder, A.Z.; Prados-Rosales, R.; Souza, A.C.; Kim, R.S.; Glatman-Freedman, A.; Joe, M.; Bai, Y.; Lowary, T.L.; et al. Association of Human Antibodies to Arabinomannan with Enhanced Mycobacterial Opsonophagocytosis and Intracellular Growth Reduction. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization. Immunization Dashboard. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Ravesloot-Chavez, M.M.; Van Dis, E.; Stanley, S.A. The Innate Immune Response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Norazmi, M.N. Pattern recognition receptors and cytokines in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection–the double-edged sword? Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 179174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, T.; Phyu, S.; Nilsen, R.; Jonsson, R.; Bjune, G. A mouse model for slowly progressive primary tuberculosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 1999, 50, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogia, P.G.; Rawat, G.; Sharma, R.K.; Aggarawal, A.; Dogra, S. Disseminated Tuberculosis: Rare Presentation. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2024, 72, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, D.R.; Hatherill, M.; Van Der Meeren, O.; Ginsberg, A.M.; Van Brakel, E.; Salaun, B.; Scriba, T.J.; Akite, E.J.; Ayles, H.M.; Bollaerts, A.; et al. Final Analysis of a Trial of M72/AS01(E) Vaccine to Prevent Tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Ghoshal, A.; Dwivedi, V.P.; Bhaskar, A. Tuberculosis: The success tale of less explored dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1079569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hagopian, B.; Tan, S. Cholesterol metabolism and intrabacterial potassium homeostasis are intrinsically related in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bah, A.; Sanicas, M.; Nigou, J.; Guilhot, C.; Astarie-Dequeker, C.; Vergne, I. The Lipid Virulence Factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Exert Multilayered Control over Autophagy-Related Pathways in Infected Human Macrophages. Cells 2020, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalera, K.; Liu, R.; Lim, J.; Pathirage, R.; Swanson, D.H.; Johnson, U.G.; Stothard, A.I.; Lee, J.J.; Poston, A.W.; Woodruff, P.J.; et al. Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis Persistence through Inhibition of the Trehalose Catalytic Shift. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tameris, M.D.; Hatherill, M.; Landry, B.S.; Scriba, T.J.; Snowden, M.A.; Lockhart, S.; Shea, J.E.; McClain, J.B.; Hussey, G.D.; Hanekom, W.A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of MVA85A, a new tuberculosis vaccine, in infants previously vaccinated with BCG: A randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tian, S.; Yu, R.; Deng, C.; Wei, R.; Chen, H.; et al. A novel nanoparticle vaccine displaying multistage tuberculosis antigens confers protection in mice infected with H37Rv. NPJ Vaccines 2025, 10, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, C.; Hoang, T.; Dietrich, J.; Cardona, P.J.; Izzo, A.; Dolganov, G.; Schoolnik, G.K.; Cassidy, J.P.; Billeskov, R.; Andersen, P. A multistage tuberculosis vaccine that confers efficient protection before and after exposure. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Peng, J.; Bai, C.; Liu, X.; Hu, L.; Luo, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; et al. Multi-Stage Tuberculosis Subunit Vaccine Candidate LT69 Provides High Protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Teng, X.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Wu, Y.; Tian, M.; Zhou, Z.; Li, L. A Multistage Subunit Vaccine Effectively Protects Mice Against Primary Progressive Tuberculosis, Latency and Reactivation. EBioMedicine 2017, 22, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagawa, Z.K.; Goman, C.; Frevol, A.; Blazevic, A.; Tennant, J.; Fisher, B.; Day, T.; Jackson, S.; Lemiale, F.; Toussaint, L.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a thermostable ID93 + GLA-SE tuberculosis vaccine candidate in healthy adults. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenum, S.; Tonby, K.; Rueegg, C.S.; Ruhwald, M.; Kristiansen, M.P.; Bang, P.; Olsen, I.C.; Sellaeg, K.; Rostad, K.; Mustafa, T.; et al. A Phase I/II randomized trial of H56:IC31 vaccination and adjunctive cyclooxygenase-2-inhibitor treatment in tuberculosis patients. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.H.; Russell, M.; Tait, D.; Scriba, T.J.; Nemes, E.; Skallerup, P.; van Brakel, E.; Cabibbe, A.M.; Cirillo, D.M.; Leuvennink-Steyn, M.; et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy of the vaccine H56:IC31 in reducing the rate of tuberculosis disease recurrence in HIV-negative adults successfully treated for drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Pahari, S.; Vidyarthi, A.; Aqdas, M.; Agrewala, J.N. NOD-2 and TLR-4 Signaling Reinforces the Efficacy of Dendritic Cells and Reduces the Dose of TB Drugs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Innate Immun. 2016, 8, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadia, H.K.; Siegel, S.J. Poly Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier. Polymers 2011, 3, 1377–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szachniewicz, M.M.; Neustrup, M.A.; van den Eeden, S.J.F.; van Meijgaarden, K.E.; Franken, K.; van Veen, S.; Koning, R.I.; Limpens, R.; Geluk, A.; Bouwstra, J.A.; et al. Evaluation of PLGA, lipid-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles, and cationic pH-sensitive liposomes as tuberculosis vaccine delivery systems in a Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge mouse model—A comparison. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 666, 124842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.B.; Geary, S.M.; Salem, A.K. Biodegradable particles as vaccine delivery systems: Size matters. AAPS J. 2013, 15, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.L.; Soema, P.C.; Slutter, B.; Ossendorp, F.; Jiskoot, W. PLGA particulate delivery systems for subunit vaccines: Linking particle properties to immunogenicity. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavishna, R.; Olafsdottir, T.A.; Brynjolfsson, S.F.; Christensen, D.; Gustafsson-Hedberg, T.; Andersen, P.; Terrinoni, M.; Holmgren, J.; Harandi, A.M. Heterologous prime-boost immunization combining parenteral and mucosal routes with different adjuvants mounts long-lived CD4+ T cell responses in lungs. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1599713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, J.L.; Chan, J.; Triebold, K.J.; Dalton, D.K.; Stewart, T.A.; Bloom, B.R. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 1993, 178, 2249–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, R.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; Slight, S.; Lin, Y.; Nawar, H.F.; Fallert Junecko, B.A.; Reinhart, T.A.; Kolls, J.; Randall, T.D.; Connell, T.D.; et al. Interleukin-17-dependent CXCL13 mediates mucosal vaccine-induced immunity against tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2013, 6, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monin, L.; Griffiths, K.L.; Slight, S.; Lin, Y.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; Khader, S.A. Immune requirements for protective Th17 recall responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counoupas, C.; Ferrell, K.C.; Ashhurst, A.; Bhattacharyya, N.D.; Nagalingam, G.; Stewart, E.L.; Feng, C.G.; Petrovsky, N.; Britton, W.J.; Triccas, J.A. Mucosal delivery of a multistage subunit vaccine promotes development of lung-resident memory T cells and affords interleukin-17-dependent protection against pulmonary tuberculosis. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Javid, B. Antibodies and tuberculosis: Finally coming of age? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Reljic, R.; Naylor, I.; Clark, S.O.; Falero-Diaz, G.; Singh, M.; Challacombe, S.; Marsh, P.D.; Ivanyi, J. Passive protection with immunoglobulin A antibodies against tuberculous early infection of the lungs. Immunology 2004, 111, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achkar, J.M.; Casadevall, A. Antibody-mediated immunity against tuberculosis: Implications for vaccine development. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, E.B.; Darrah, P.A.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; McNamara, R.P.; Roederer, M.; Seder, R.A.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; Flynn, J.L.; Fortune, S.M.; et al. Humoral correlates of protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis following intravenous BCG vaccination in rhesus macaques. iScience 2024, 27, 111128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, N.S.; Curtis, N.C.; Lahey, T.P.; Wieland-Alter, W.; Stout, J.E.; Larson, E.C.; Jauro, S.; Scanga, C.A.; Darrah, P.A.; Roederer, M.; et al. Humoral correlate of vaccine-mediated protection from tuberculosis identified in humans and non-human primates. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.E.; Zewdie, M.; Mussa, D.; Abebe, Y.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M.; Franken, K.; Abebe, F.; Wassie, L. The role of IgA and IgG in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: A cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2025, uxaf001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, B.; Keeble, J.; Dagg, B.; Kaveh, D.A.; Hogarth, P.J.; Ho, M.M. Efficacy and immunogenicity of different BCG doses in BALB/c and CB6F1 mice when challenged with H37Rv or Beijing HN878. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmia, N.; Ramsay, A.J. Prime-boost approaches to tuberculosis vaccine development. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2012, 11, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biketov, S.; Potapov, V.; Ganina, E.; Downing, K.; Kana, B.D.; Kaprelyants, A. The role of resuscitation promoting factors in pathogenesis and reactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during intra-peritoneal infection in mice. BMC Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyrolles, O.; Hernandez-Pando, R.; Pietri-Rouxel, F.; Fornes, P.; Tailleux, L.; Barrios Payan, J.A.; Pivert, E.; Bordat, Y.; Aguilar, D.; Prevost, M.C.; et al. Is adipose tissue a place for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence? PLoS ONE 2006, 1, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, A.; Nichols, J.; Li, J.C.; Flynn, C.E.; Facciolo, K. Disseminated Tuberculosis Involving Lung, Peritoneum, and Endometrium in an Immunocompetent 17-Year-Old Patient. Cureus 2020, 12, e9081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization. TB Knowledge Sharing Platform. Available online: https://tbksp.who.int/en/node/3024 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Moule, M.G.; Cirillo, J.D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Dissemination Plays a Critical Role in Pathogenesis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.L.; Olsen, M.; Jagannath, C.; Actor, J.K. Trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate and lipid in the pathogenesis of caseating granulomas of tuberculosis in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramnik, I.; Beamer, G. Mouse models of human TB pathology: Roles in the analysis of necrosis and the development of host-directed therapies. Semin. Immunopathol. 2016, 38, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.; Ruedas-Torres, I.; Agullo-Ros, I.; Rayner, E.; Salguero, F.J. Comparative pathology of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis in animal models. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1264833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeychuk, I.V.; Gancharova, O.S.; Gulyaev, S.A.; Gulyaeva, T.V.; Zhitkevich, A.S.; Avdoshina, D.V.; Moroz, A.V.; Lunin, A.S.; Sotskova, S.E.; Korduban, E.A.; et al. Experimental Use of Common Marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) in Preclinical Trials of Antiviral Vaccines. Acta Naturae 2024, 16, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornson-Hooper, Z.B.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Spitzer, M.H.; Chen, H.; Madhireddy, D.; Hu, K.; Lundsten, K.; McIlwain, D.R.; Nolan, G.P. A Comprehensive Atlas of Immunological Differences Between Humans, Mice, and Non-Human Primates. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 867015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tukhvatulin, A.I.; Dzharullaeva, A.S.; Vasina, D.V.; Fursov, M.V.; Izhaeva, F.M.; Kleymenov, D.A.; Shcherbinin, D.N.; Polyakov, N.B.; Solovyev, A.I.; Zhukhovitsky, V.G.; et al. Novel Multistage Subunit Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nanoparticle Vaccine Confers Protection Against Experimental Infection in Prophylactic and Therapeutic Regimens. Vaccines 2026, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010005

Tukhvatulin AI, Dzharullaeva AS, Vasina DV, Fursov MV, Izhaeva FM, Kleymenov DA, Shcherbinin DN, Polyakov NB, Solovyev AI, Zhukhovitsky VG, et al. Novel Multistage Subunit Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nanoparticle Vaccine Confers Protection Against Experimental Infection in Prophylactic and Therapeutic Regimens. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleTukhvatulin, Amir I., Alina S. Dzharullaeva, Daria V. Vasina, Mikhail V. Fursov, Fatima M. Izhaeva, Denis A. Kleymenov, Dmitry N. Shcherbinin, Nikita B. Polyakov, Andrey I. Solovyev, Vladimir G. Zhukhovitsky, and et al. 2026. "Novel Multistage Subunit Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nanoparticle Vaccine Confers Protection Against Experimental Infection in Prophylactic and Therapeutic Regimens" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010005

APA StyleTukhvatulin, A. I., Dzharullaeva, A. S., Vasina, D. V., Fursov, M. V., Izhaeva, F. M., Kleymenov, D. A., Shcherbinin, D. N., Polyakov, N. B., Solovyev, A. I., Zhukhovitsky, V. G., Zhitkevich, A. S., Gordeychuk, I. V., Litvinova, A. M., Manuylov, V. A., Potapov, V. D., Tkachuk, A. P., Gushchin, V. A., Logunov, D. Y., & Gintsburg, A. L. (2026). Novel Multistage Subunit Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nanoparticle Vaccine Confers Protection Against Experimental Infection in Prophylactic and Therapeutic Regimens. Vaccines, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010005