Virus-like Particles Carrying a Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Peptide Induce an Antibody Response and Reduce Viral Load in Immunized Pigs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vaccine

2.2. PCV2b Challenge Virus

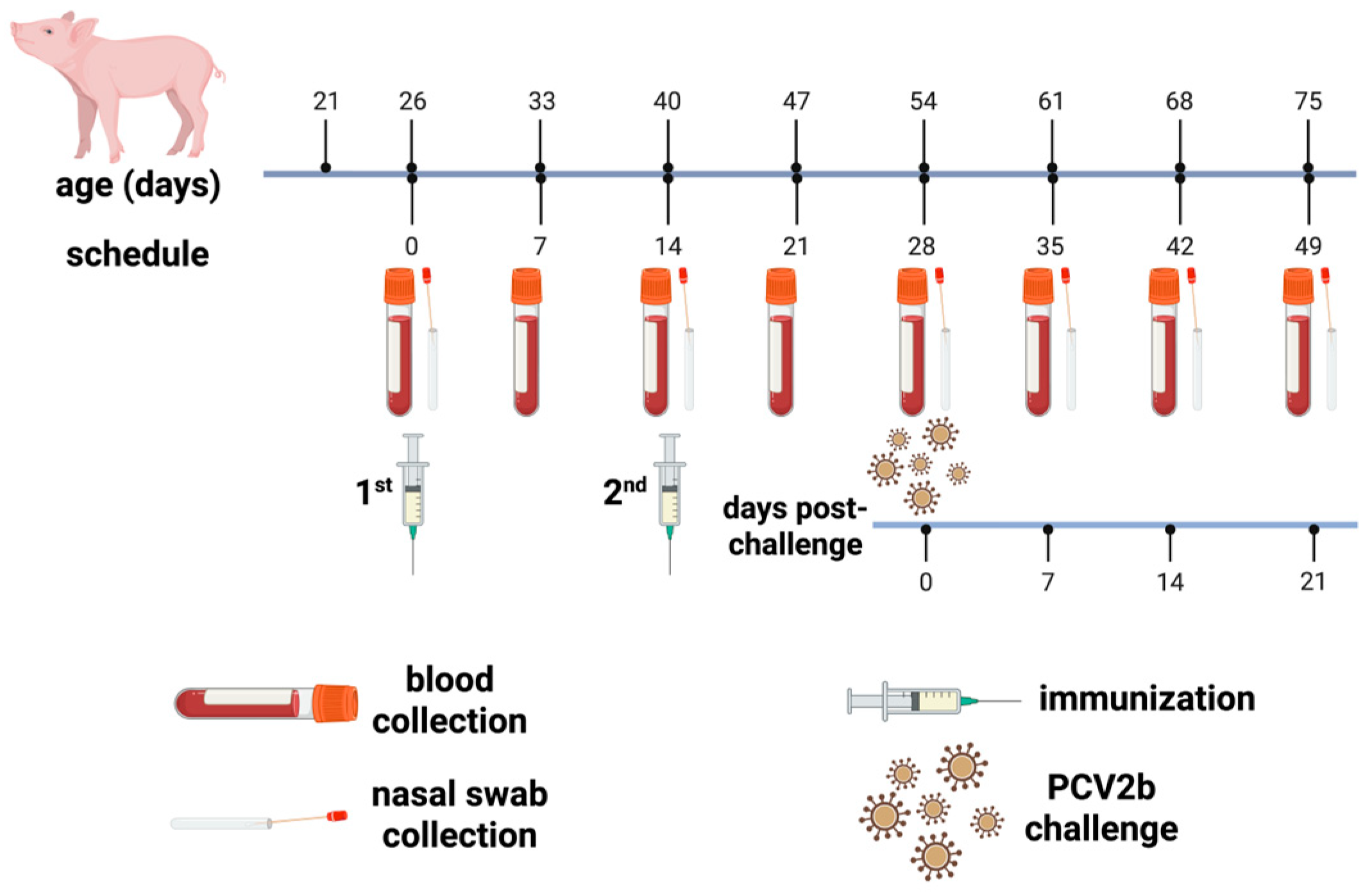

2.3. Animal Immunization, Challenge, and Sampling

2.3.1. Animal Immunization

2.3.2. Viral Challenge

2.3.3. Sample Collection and Body-Weight Tracking

2.4. Antibody Assay

2.5. Cytokine Profiling

2.6. PCV2 Genome Presence in Nasal Swabs and Organs by Real-Time PCR

2.7. Histopathological Score

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

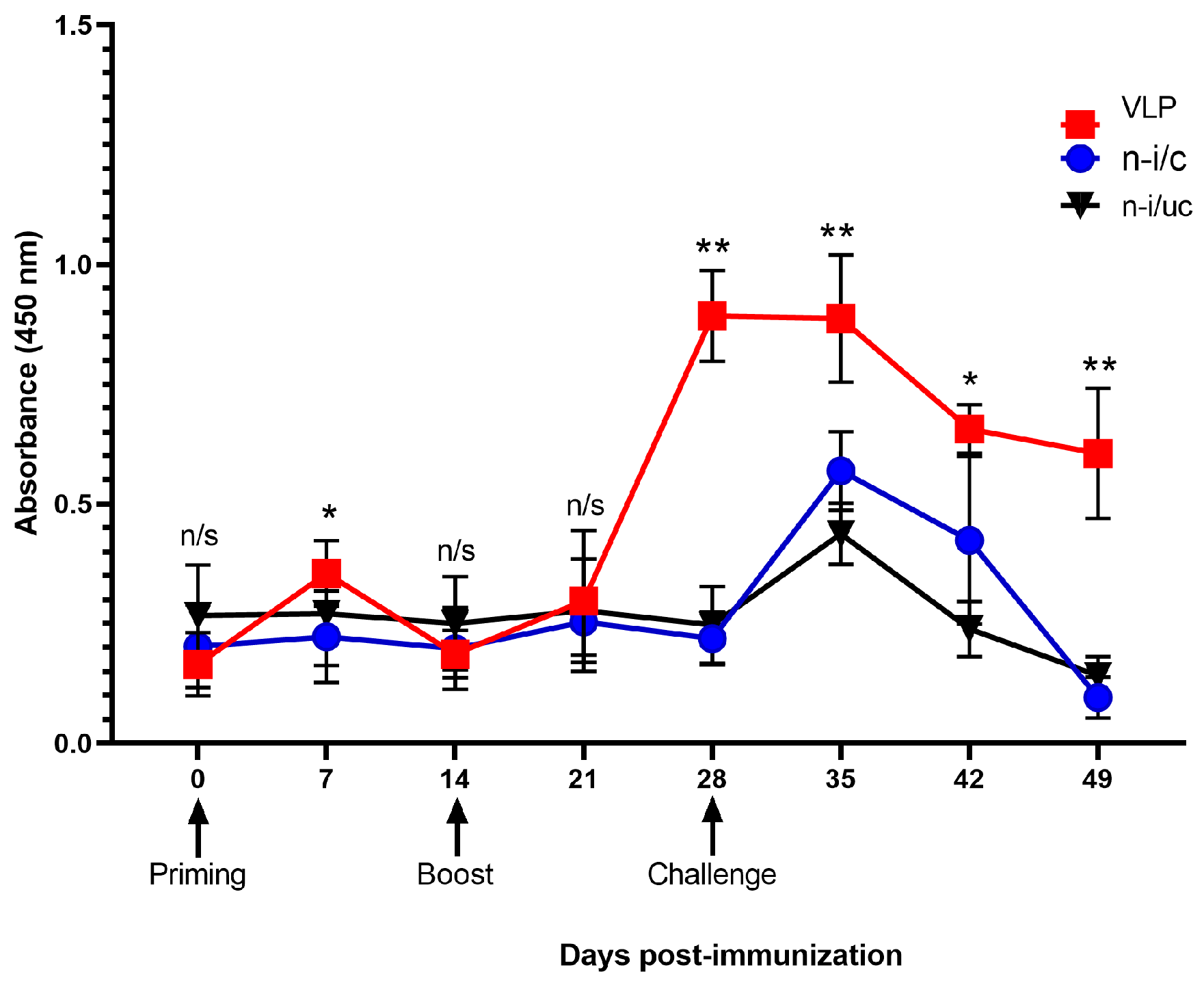

3.1. VLPs Carrying a PCV2 Peptide Induce Peptide-Specific IgG Antibodies in Immunized Animals Under a Prime-BOOST Scheme

3.2. VLPs Carrying a PCV2 Peptide Induce Anti-Inflammatory/Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Immunized Animals

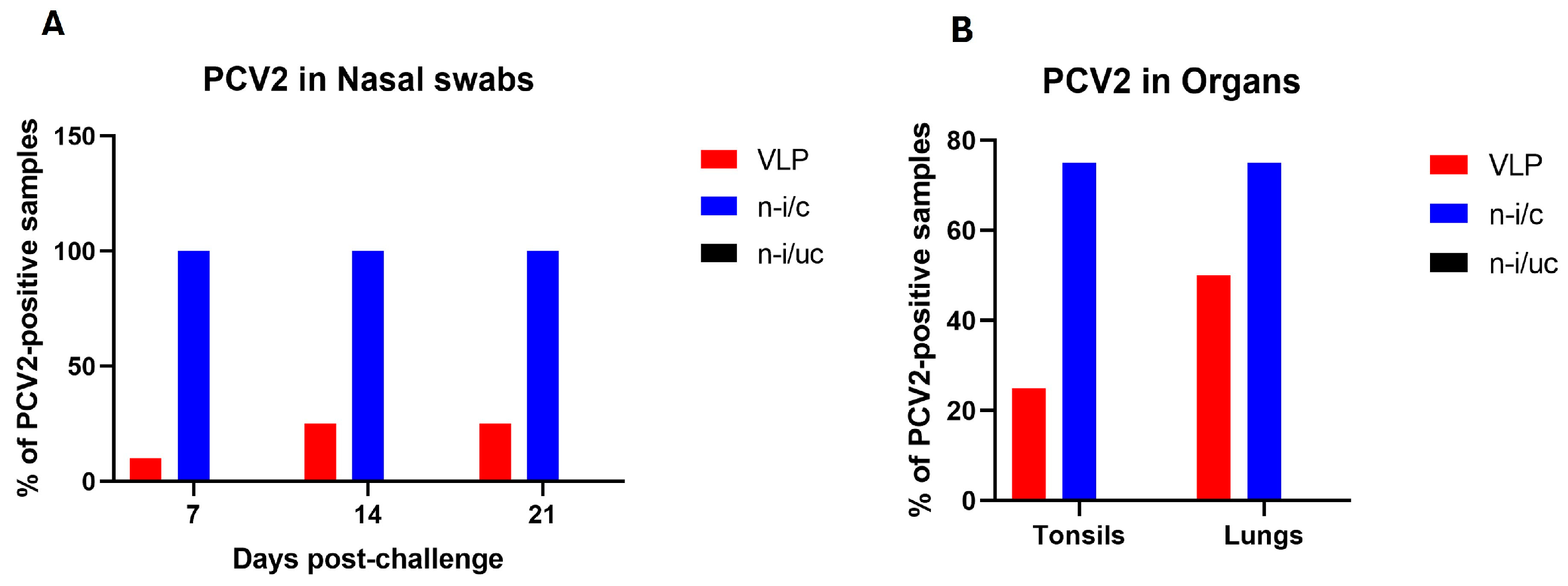

3.3. VLPs Carrying a PCV2 Peptide Reduce Viral Shedding and Presence in Tonsils and Lungs of Immunized Animals Challenged with a PCV2 Isolate

3.4. VLPs Carrying a PCV2 Peptide Showed No Effect on Daily Weight Gain and Macroscopic and Histopathological Lesions in Lungs, Spleens, Tonsils, and Lymph Nodes of Immunized Animals Challenged with a PCV2 Isolate

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patterson, A.R.; Opriessnig, T. Epidemiology and horizontal transmission of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2). Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2010, 11, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.; Opriessnig, T.; Meng, X.J.; Pelzer, K.; Buechner-Maxwell, V. Porcine circovirus type 2 and porcine circovirus-associated disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2009, 23, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemann, M.; Beach, N.M.; Meng, X.J.; Halbur, P.G.; Opriessnig, T. Vaccination with inactivated or live-attenuated chimeric PCV1-2 results in decreased viremia in challenge-exposed pigs and may reduce transmission of PCV2. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 158, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tischer, I.; Gelderblom, H.; Vettermann, W.; Koch, M.A. A very small porcine virus with circular single-stranded DNA. Nature 1982, 295, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.Z.; Guo, K.K.; Zhang, Y.M. Current understanding of genomic DNA of porcine circovirus type 2. Virus Genes 2014, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Hou, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, D.; Cui, Y.; Feng, X.; Liu, J. Porcine Circovirus Type 2 Vaccines: Commercial Application and Research Advances. Viruses 2022, 14, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Lu, Q.; Wang, F.; Xing, G.; Feng, H.; Jin, Q.; Guo, Z.; Teng, M.; Hao, H.; Li, D.; et al. Phylogenetic analysis of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) between 2015 and 2018 in Henan Province, China. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Segalés, J. Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV-2) genotype update and proposal of a new genotyping methodology. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortey, M.; Pileri, E.; Sibila, M.; Pujols, J.; Balasch, M.; Plana, J.; Segalés, J. Genotypic shift of porcine circovirus type 2 from PCV-2a to PCV-2b in Spain from 1985 to 2008. Vet. J. 2011, 187, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.T.; Halbur, P.G.; Opriessnig, T. Global molecular genetic analysis of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) sequences confirms the presence of four main PCV2 genotypes and reveals a rapid increase of PCV2d. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Segalés, J. Porcine Circovirus 2 Genotypes, Immunity and Vaccines: Multiple Genotypes but One Single Serotype. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fort, M.; Sibila, M.; Allepuz, A.; Mateu, E.; Roerink, F.; Segalés, J. Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) vaccination of conventional pigs prevents viremia against PCV2 isolates of different genotypes and geographic origins. Vaccine 2008, 26, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraile, L.; Grau-Roma, L.; Sarasola, P.; Sinovas, N.; Nofrarías, M.; López-Jimenez, R.; López-Soria, S.; Sibila, M.; Segalés, J. Inactivated PCV2 one shot vaccine applied in 3-week-old piglets: Improvement of production parameters and interaction with maternally derived immunity. Vaccine 2012, 30, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenaux, M.; Opriessnig, T.; Halbur, P.G.; Elvinger, F.; Meng, X.J. A chimeric porcine circovirus (PCV) with the immunogenic capsid gene of the pathogenic PCV type 2 (PCV2) cloned into the genomic backbone of the nonpathogenic PCV1 induces protective immunity against PCV2 infection in pigs. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6297–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, P.; Mahé, D.; Cariolet, R.; Keranflec’h, A.; Baudouard, M.A.; Cordioli, P.; Albina, E.; Jestin, A. Protection of swine against post-weaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS) by porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) proteins. Vaccine 2003, 21, 4565–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, M.; Sibila, M.; Pérez-Martín, E.; Nofrarías, M.; Mateu, E.; Segalés, J. One dose of a porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) sub-unit vaccine administered to 3-week-old conventional piglets elicits cell-mediated immunity and significantly reduces PCV2 viremia in an experimental model. Vaccine 2009, 27, 4031–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, N.M.; Ramamoorthy, S.; Opriessnig, T.; Wu, S.Q.; Meng, X.J. Novel chimeric porcine circovirus (PCV) with the capsid gene of the emerging PCV2b subtype cloned in the genomic backbone of the non-pathogenic PCV1 is attenuated in vivo and induces protective and cross-protective immunity against PCV2b and PCV2a subtypes in pigs. Vaccine 2010, 29, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylla, S.; Cong, Y.L.; Sun, Y.X.; Yang, G.L.; Ding, X.M.; Yang, Z.Q.; Zhou, Y.L.; Yang, M.; Wang, C.F.; Ding, Z. Protective immunity conferred by porcine circovirus 2 ORF2-based DNA vaccine in mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 58, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.; Gamage, L.N.; Hayes, C. Dual expression system for assembling phage lambda display particle (LDP) vaccine to porcine Circovirus 2 (PCV2). Vaccine 2010, 28, 6789–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.; Lin, W.L.; Wu, C.M.; Chi, J.N.; Chien, M.S.; Huang, C. Characterization of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) capsid particle assembly and its application to virus-like particle vaccine development. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1501–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.N.; Wu, C.Y.; Chien, M.S.; Wu, P.C.; Wu, C.M.; Huang, C. The preparation of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) virus-like particles using a recombinant pseudorabies virus and its application to vaccine development. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 181, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xin, G.; Zhou, X.; Lu, H.; Zhang, X.; Xia, X.; Sun, H. Comparative evaluation of ELPylated virus-like particle vaccine with two commercial PCV2 vaccines by experimental challenge. Vaccine 2020, 38, 3952–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.X.; Ma, Z.; Yang, X.Q.; Fan, H.J.; Lu, C.P. A novel vaccine against Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) and Streptococcus equi ssp. zooepidemicus (SEZ) co-infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 171, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavulraj, S.; Pannhorst, K.; Stout, R.W.; Paulsen, D.B.; Carossino, M.; Meyer, D.; Becher, P.; Chowdhury, S.I. A Triple Gene-Deleted Pseudorabies Virus-Vectored Subunit PCV2b and CSFV Vaccine Protects Pigs against PCV2b Challenge and Induces Serum Neutralizing Antibody Response against CSFV. Vaccines 2022, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Hu, W.; Zhou, B.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Yan, Q.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Ding, H.; Zhao, M.; et al. Immunogenicity and Immunoprotection of PCV2 Virus-like Particles Incorporating Dominant T and B Cell Antigenic Epitopes Paired with CD154 Molecules in Piglets and Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyvushko, O.; Rakibuzzaman, A.; Pillatzki, A.; Webb, B.; Ramamoorthy, S. Efficacy of a Commercial PCV2a Vaccine with a Two-Dose Regimen Against PCV2d. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.B.; Jin, Y.L.; Jiang, X.T.; Zhou, J.Y.; Zhang, X.; Xing, G.; He, J.L.; Yan, Y. Fine mapping of antigenic epitopes on capsid proteins of porcine circovirus, and antigenic phenotype of porcine circovirus type 2. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 46, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aviña, A.S.; Mendoza-Gómez, L.F.; Hernández-Mancillas, X.D.; Salazar-González, J.A.; Zapata-Cuellar, L.; Camacho-Ruiz, R.M.; Comas-García, M.; Sarmiento-Silva, R.E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Arellano-Plaza, M.; et al. Design of a Golden Gate Cloning Plasmid for the Generation of a Chimeric Virus-Like Particle-Based Subunit Vaccine Against Porcine Circovirus Type 2. Mol. Biotechnol. 2024, 67, 4329–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarneri, F.; Tonni, M.; Sarli, G.; Boniotti, M.B.; Lelli, D.; Barbieri, I.; D’Annunzio, G.; Alborali, G.L.; Bacci, B.; Amadori, M. Non-Assembled ORF2 Capsid Protein of Porcine Circovirus 2b Does Not Confer Protective Immunity. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hall, J. Embedding. In Laboratory Methods in Histotechnology; Prophet, E.B., Mills, B., Arrington, J.B., Sobin, L.H., Eds.; American Registry of Pathology: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.C. Hematoxylin and eosin. In Laboratory Methods in Histotechnology; Prophet, E.B., Mills, B., Arrington, J.B., Sobin, L.H., Eds.; American Registry of Pathology: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, S.; Khasa, Y.P. Challenges and Opportunities in the Process Development of Chimeric Vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Segalés, J. Circovirus porcino tipo 2. In Complejo Respiratorio Porcino; Martelli, P., Segalés, J., Torremorell, M., Canelli, E., Maes, D., Nathues, H., Brockmeier, S., Gottschalk, M., Aragón-Fernández, V., Eds.; SERVET: Zaragoza, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Jia, C.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, E.M. A nanobody-horseradish peroxidase fusion protein-based competitive ELISA for rapid detection of antibodies against porcine circovirus type 2. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, C. Development of a blocking ELISA for detection of serum neutralizing antibodies against porcine circovirus type 2. J. Virol. Methods 2011, 171, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedolla-López, F.; Trujillo-Ortega, M.E.; Mendoza-Elvira, S.; Quintero-Ramírez, V.; Alonso-Morales, R.; Ramírez-Mendoza, H.; Sánchez-Betancourt, J.I. Identification and genotyping of porcine circovirus type II (PCV2) in Mexico. Virus Dis. 2018, 29, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.W.; Han, K.; Park, C.; Chae, C. Clinical, virological, immunological and pathological evaluation of four porcine circovirus type 2 vaccines. Vet. J. 2014, 200, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalés, J.; Allan, G.M.; Domingo, M. Porcine circovirus diseases. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2005, 6, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, I.; Okuda, Y.; Yazawa, S.; Ono, M.; Sasaki, T.; Itagaki, M.; Nakajima, M.; Okabe, Y.; Hidejima, I. PCR detection of Porcine circovirus type 2 DNA in whole blood, serum, oropharyngeal swab, nasal swab, and feces from experimentally infected pigs and field cases. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2003, 65, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Suárez, C.; Martínez-Lobo, F.J.; Segalés-I Coma, J.; Carvajal-Urueña, A.M. Enfermedades Infecciosas del Ganado Porcino; SERVET: Zaragoza, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Cytokine | Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunized/Challenged (µg/mL) | Non-Immunized/Challenged (µg/mL) | Non-Immunized/Unchallenged (µg/mL) | ||||

| 21d | 35d | 21d | 35d | 21d | 35d | |

| IL-4 | <61 | 341.8 | <61 | 62 | <61 | 1011.35 |

| IL-10 | <24 | 252.1 | <24 | <24 | <24 | 48.6 |

| IL-1Ra | 140.5 | 262.6 | 42.1 | 176.2 | 24.2 | 110.5 |

| IL-1α | 4.2 | 17.6 | 9.8 | 14.2 | 3.8 | 27.3 |

| TNF-α | <24 | <24 | 79.4 | <24 | <24 | <24 |

| IFN-γ | 855.7 | <122 | 1499 | <122 | <122 | <122 |

| GM-CSF | <24 | <24 | <24 | <24 | <24 | <24 |

| IL-8 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | <12 | 164.9 |

| IL-12 | 437.3 | 555.8 | 216.7 | 262.8 | 145.1 | 550 |

| IL-18 | 299.6 | 518.9 | 153.5 | 178.6 | 165.7 | 347.4 |

| IL-1β | <122 | <122 | <122 | <122 | <122 | <122 |

| IL-6 | <24 | 43.3 | <24 | <24 | <24 | <24 |

| IL-2 | <24 | <24 | <24 | <24 | <24 | 39.1 |

| Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunized/Challenged | Non-Immunized/Challenged | Non-Immunized/Unchallenged | |

| initial weight (day 0) (kg) | 8.98 ± 0.98 | 9.76 ± 1.27 | 8.9 ± 1.21 |

| final weight (day 49) (kg) | 38.63 ± 3.49 | 39.08 ± 3.36 | 43.65 ± 3.49 |

| weight gain (kg) | 29.65 | 29.32 | 34.75 |

| daily weight gain (kg) | 0.54 ± 0.07 a | 0.54 ± 0.07 a | 0.62 ± 0.10 b |

| Lesion | Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunized/Challenged | Non-Immunized/Challenged | Non-Immunized/Unchallenged | |

| tonsil and inguinal lymphadenomegalia * | 2/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

| edematous interlobular septa * | 10/10 | 9/10 | 8/10 |

| lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia | +, ++ | +, + | +, + |

| class 2 pneumonia | +, ++ | +, + | -, - |

| spleen follicular hyperplasia | +, + | ++, +++ | -, - |

| spleen lymphoid hyperplasia | +, ++ | +, + | +, + |

| tonsil and inguinal lymph node follicular hyperplasia | +, ++ | ++, ++ | +, + |

| tonsil and inguinal lymph node lymphoid hyperplasia | ++, +++ | ++, ++ | +, + |

| tonsil and inguinal lymph node necrosis | ++, ++ | ++, ++ | -, - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hernández-Aviña, A.d.S.; Cuéllar-Galván, M.A.; Salazar-González, J.A.; Albarrán-Velázquez, O.A.; Beltrán-Juárez, M.d.l.Á.; Segura-Velázquez, R.; Herrera-Rodríguez, S.E.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, A.; Sánchez-Betancourt, J.I. Virus-like Particles Carrying a Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Peptide Induce an Antibody Response and Reduce Viral Load in Immunized Pigs. Vaccines 2026, 14, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010024

Hernández-Aviña AdS, Cuéllar-Galván MA, Salazar-González JA, Albarrán-Velázquez OA, Beltrán-Juárez MdlÁ, Segura-Velázquez R, Herrera-Rodríguez SE, Gutiérrez-Ortega A, Sánchez-Betancourt JI. Virus-like Particles Carrying a Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Peptide Induce an Antibody Response and Reduce Viral Load in Immunized Pigs. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Aviña, Ana del Socorro, Marco Antonio Cuéllar-Galván, Jorge Alberto Salazar-González, Oscar Alejandro Albarrán-Velázquez, María de los Ángeles Beltrán-Juárez, René Segura-Velázquez, Sara Elisa Herrera-Rodríguez, Abel Gutiérrez-Ortega, and José Iván Sánchez-Betancourt. 2026. "Virus-like Particles Carrying a Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Peptide Induce an Antibody Response and Reduce Viral Load in Immunized Pigs" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010024

APA StyleHernández-Aviña, A. d. S., Cuéllar-Galván, M. A., Salazar-González, J. A., Albarrán-Velázquez, O. A., Beltrán-Juárez, M. d. l. Á., Segura-Velázquez, R., Herrera-Rodríguez, S. E., Gutiérrez-Ortega, A., & Sánchez-Betancourt, J. I. (2026). Virus-like Particles Carrying a Porcine Circovirus Type 2b Peptide Induce an Antibody Response and Reduce Viral Load in Immunized Pigs. Vaccines, 14(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010024