A Community-Based Intervention in Middle Schools in Spain to Improve HPV Vaccination Acceptance: A “Pill of Knowledge” Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

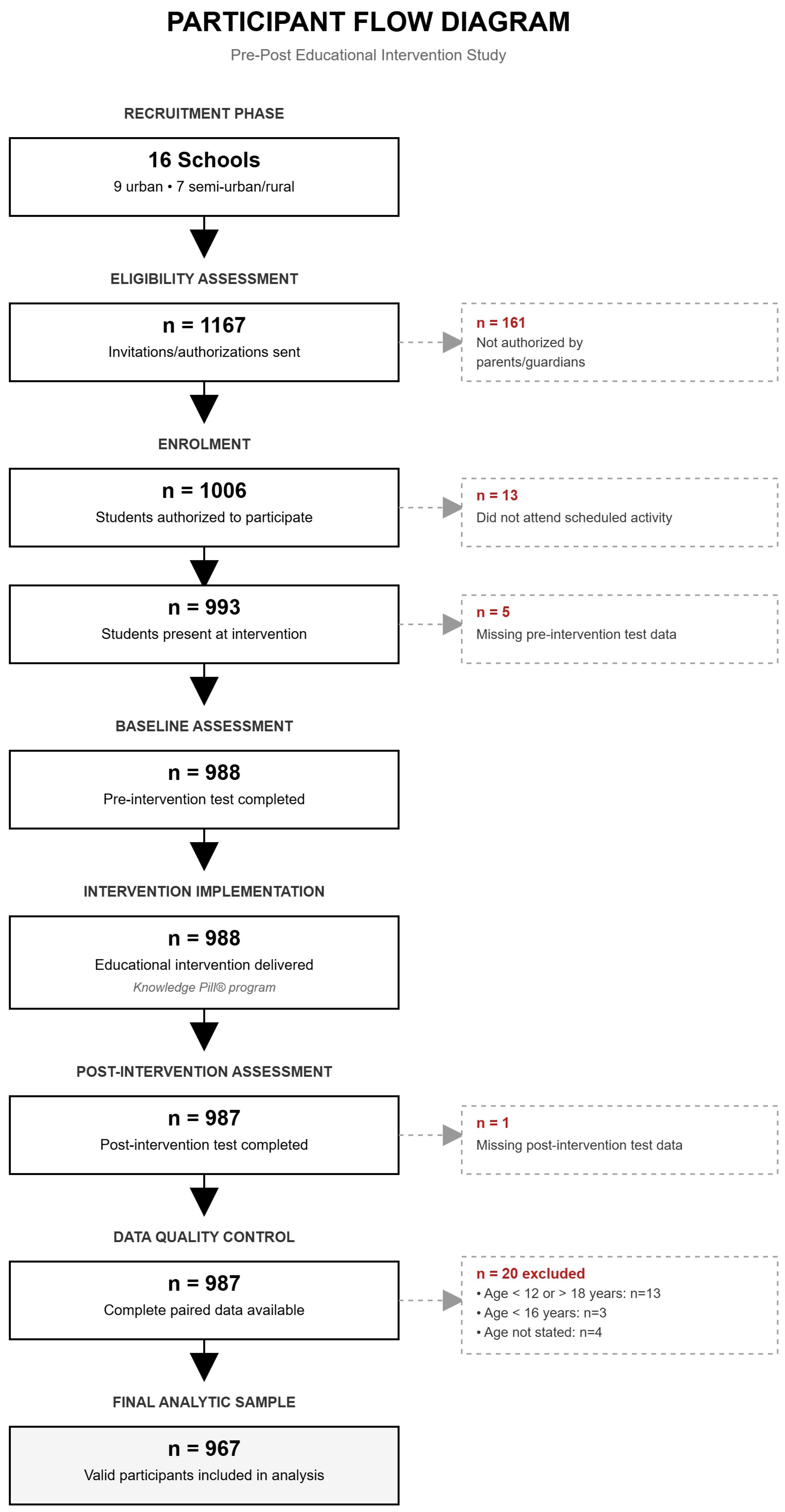

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Recruitment

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Variables Collected and Intervention Protocol

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

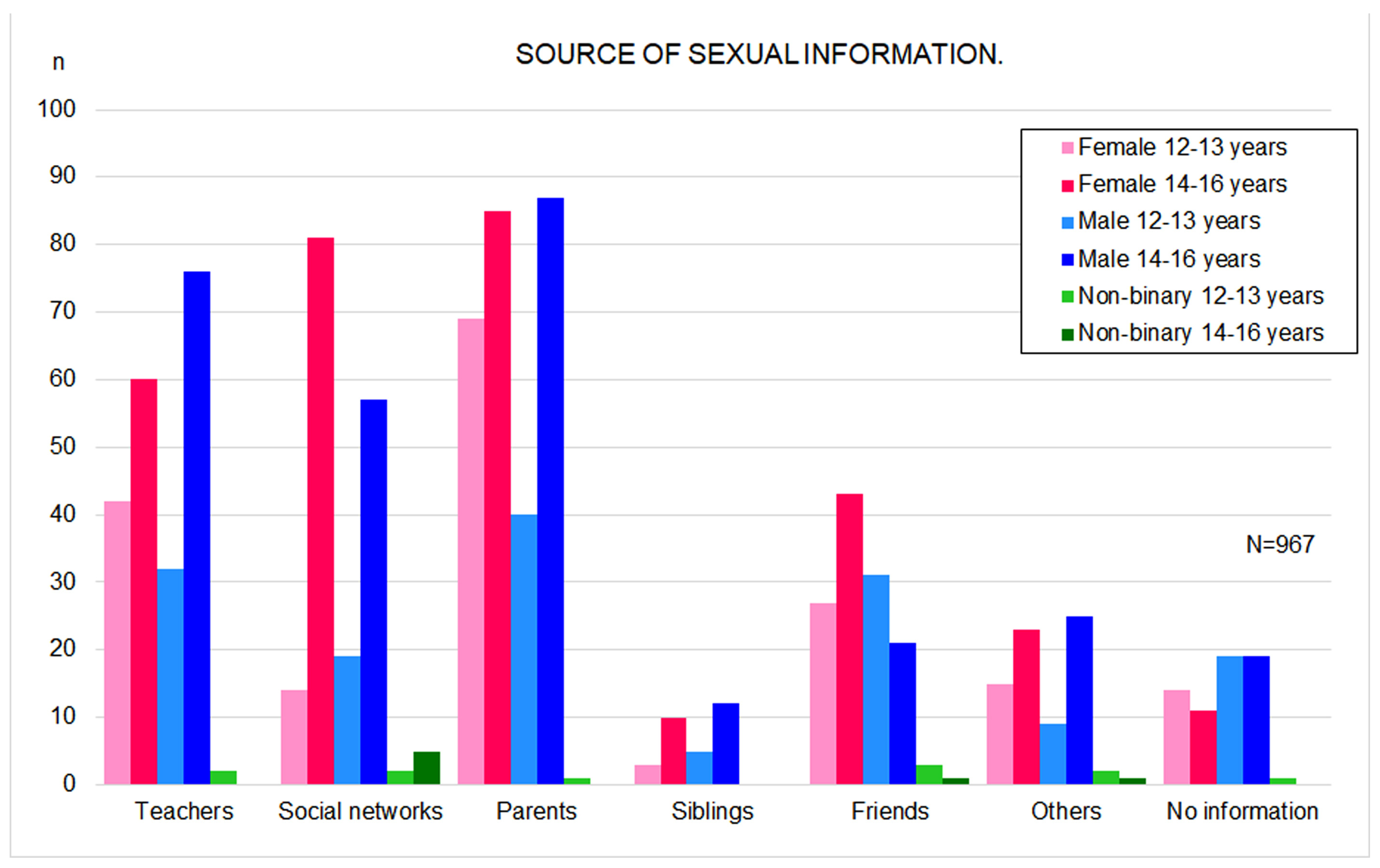

3.2. Sources of Sexual Information and Perceived Sexual Knowledge

3.3. Perceived HPV Knowledge and HPV Vaccination

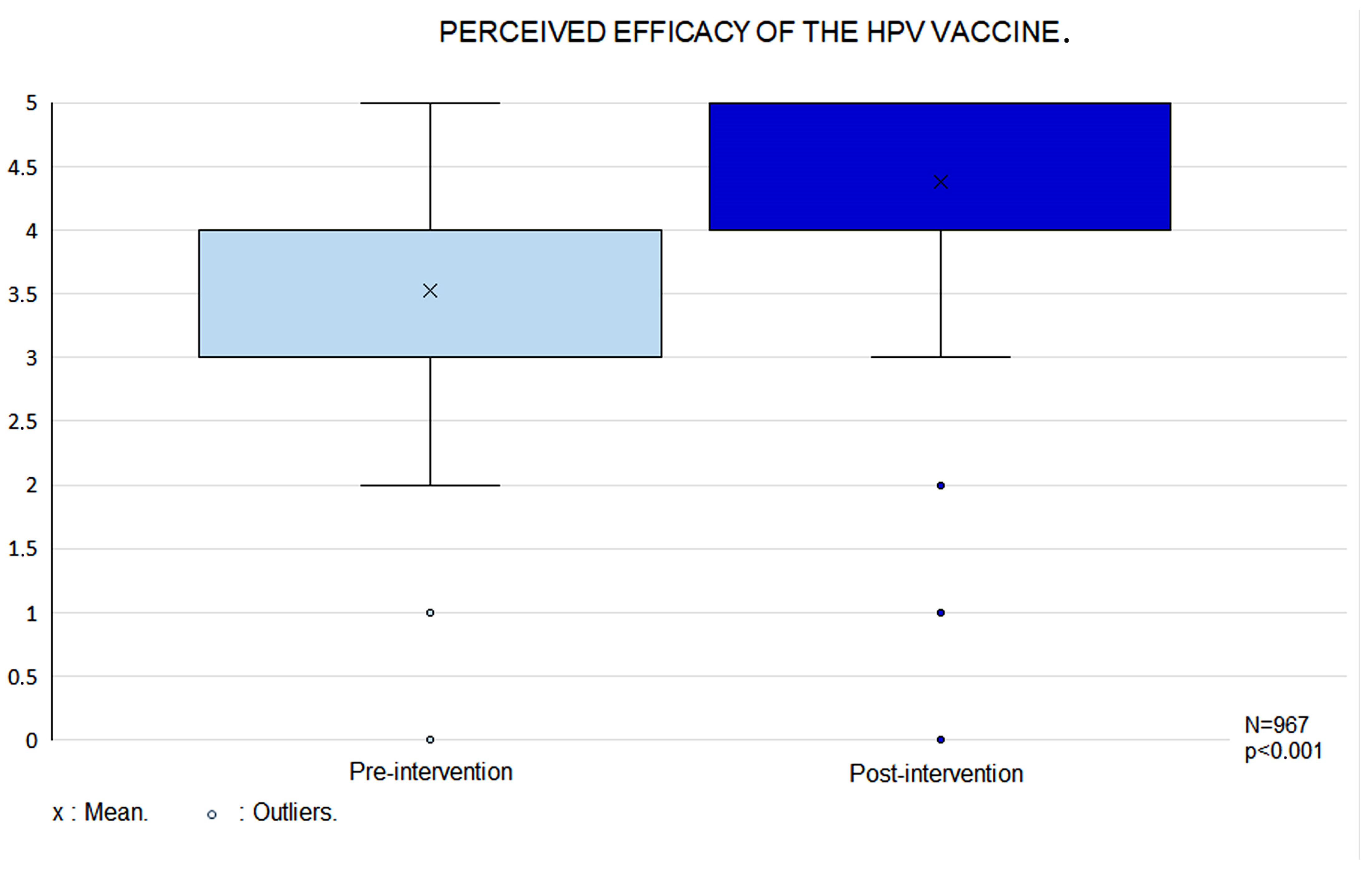

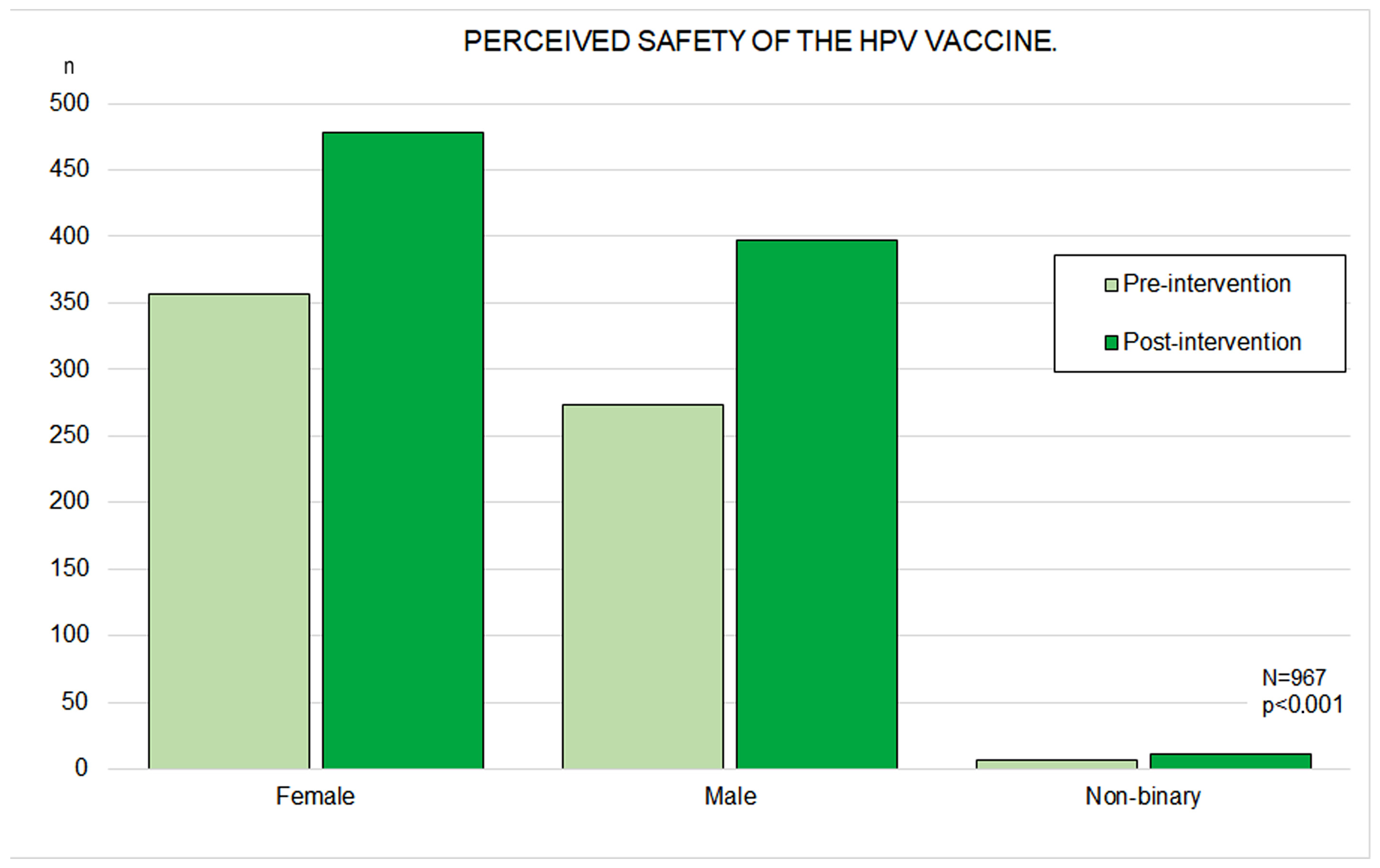

3.4. Perceived HPV Vaccine Efficacy and Safety

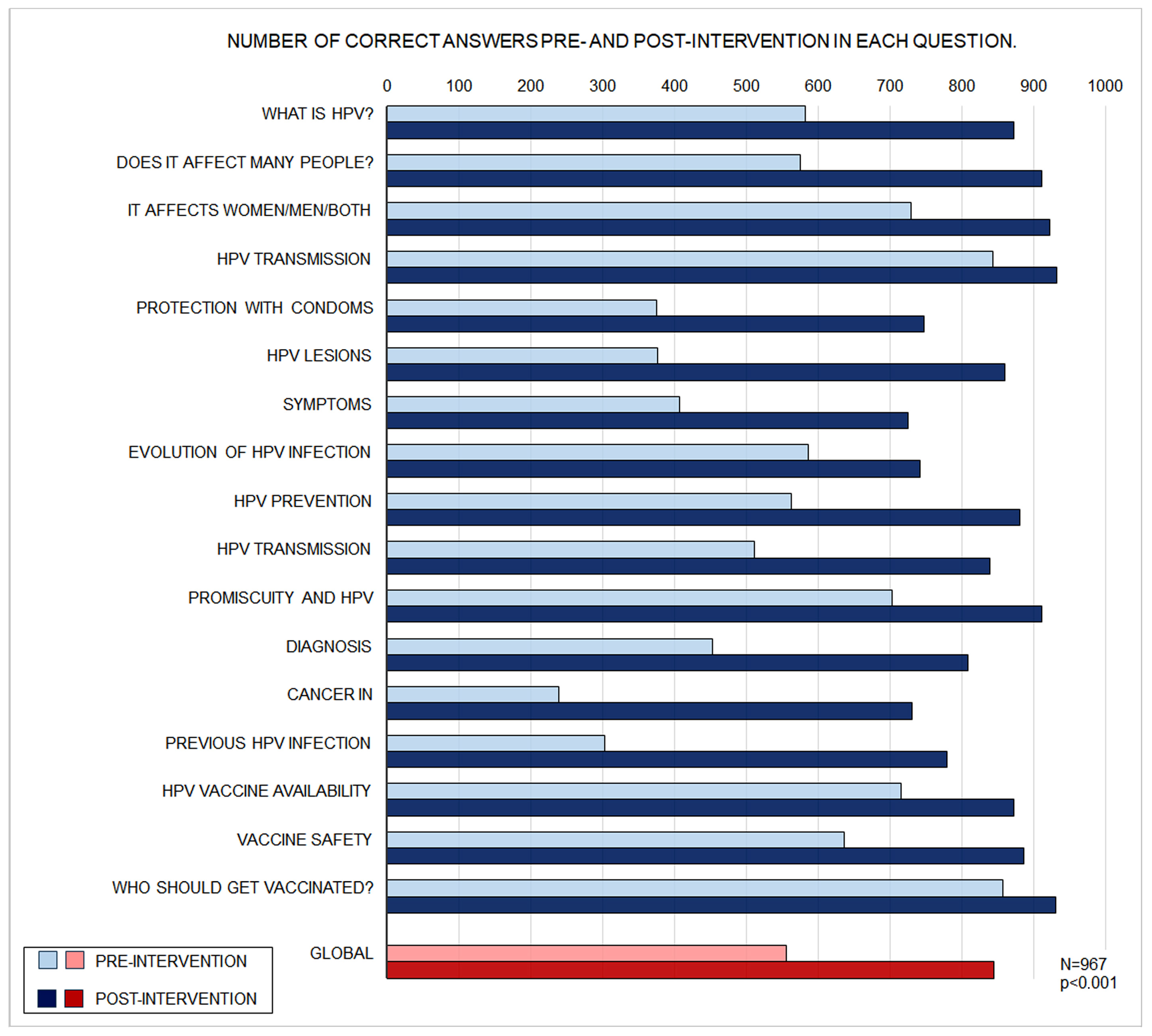

3.5. Questionnaire Performance

3.6. Vaccination Intentions

3.7. Logistic Regression Analysis of Predictors of Vaccination Intention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

References

- Szymonowicz, K.A.; Chen, J. Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer Biol. Med. 2020, 17, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, Z.Q.; Kosasih, J.; Russell, F.M.; Garland, S.M.; Mulholland, E.K.; Licciardi, P.V. Recombinant human papillomavirus nonavalent vaccine in the prevention of cancers caused by human papillomavirus. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 1951–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eClinicalMedicine. Global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem: Are we on track? eClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SERGAS. G.H.S. Immunisation Schedule Throughout Life; Instruction 20-12-2024 v9; Consellería de Sanidade: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, S.; Fleming, A.; Sahm, L.J.; Moore, A.C. Identifying intervention strategies to improve HPV vaccine decision-making using behaviour change theory. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Pouso, A.I.; González-Palanca, S.; Palmeiro-Fernández, G.; Dominguez-Salgado, J.C.; Pérez-Sayáns, M.; González-Veiga, E.J.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Daley, E.M. Parents’ perspectives on dental team as advisors to promote HPV vaccination among Spanish adolescents. J. Publ. Health Dent. 2024, 84, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musella, G.; Liguori, S.; Cantile, T.; Adamo, D.; Coppola, N.; Canfora, F.; Blasi, A.; Mignogna, M.; Amato, M.; Caponio, V.C.A.; et al. Knowledge, attitude and perception of Italian dental students toward HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer and vaccination: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Icardi, G.; Costantino, C.; Guido, M.; Zizza, A.; Restivo, V.; Amicizia, D.; Tassinari, F.; Piazza, M.F.; Paganino, C.; Casuccio, A.; et al. Burden and Prevention of HPV. Knowledge, Practices and Attitude Assessment Among Pre-Adolescents and their Parents in Italy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Amodio, E.; Vitale, F.; Trucchi, C.; Maida, C.M.; Bono, S.E.; Caracci, F.; Sannasardo, C.E.; Scarpitta, F.; Vella, C.; et al. Human Papilloma Virus Infection and Vaccination: Pre-Post Intervention Analysis on Knowledge, Attitudes and Willingness to Vaccinate Among Preadolescents Attending Secondary Schools of Palermo, Sicily. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.R.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Pu, C.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.L.; Ren, F.Y.; Li, J. Effect of an educational intervention on HPV knowledge and attitudes towards HPV and its vaccines among junior middle school students in Chengdu, China. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandahl, M.; Rosenblad, A.; Stenhammar, C.; Tyden, T.; Westerling, R.; Larsson, M.; Oscarsson, M.; Andrae, B.; Dalianis, T.; Neveus, T. School-based intervention for the prevention of HPV among adolescents: A cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, R.K.; Moehling, K.K.; Lin, C.J.; Zhang, S.; Raviotta, J.M.; Reis, E.C.; Humiston, S.G.; Nowalk, M.P. Improving adolescent HPV vaccination in a randomized controlled cluster trial using the 4 Pillars practice Transformation Program. Vaccine 2017, 35, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Rodriguez, M.; Llorca, J. Bias. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Rodriguez, I.; Rodriguez-Lopez, M.; Blanco-Hortas, A.; Da Silva-Dominguez, J.L.; Mora-Bermudez, M.J.; Varela-Centelles, P.; Santana-Mora, U. Addressing gaps in transversal educational contents in undergraduate dental education. The audio-visual ‘pill of knowledge’ approach. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 23, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, A.G.; Boyes, A.W.; Khumalo, P.G.; Mackenzie, L. Improving knowledge, attitudes, and uptake of cervical cancer prevention among female students: A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based health education. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 164, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoffery, C.; Petagna, C.; Agnone, C.; Perez, S.; Saber, L.B.; Ryan, G.; Dhir, M.; Sekar, S.; Yeager, K.A.; Biddell, C.B.; et al. A systematic review of interventions to promote HPV vaccination globally. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.Y.; Liu, T.L.; Chen, L.M.; Liu, M.J.; Chang, Y.P.; Tsai, C.S.; Yen, C.F. Determinants of Parental Intention to Vaccinate Young Adolescent Girls against the Human Papillomavirus in Taiwan: An Online Survey Study. Vaccines 2024, 12, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaresmi, M.N.; Rozanti, N.M.; Simangunsong, L.B.; Wahab, A. Improvement of Parent’s awareness, knowledge, perception, and acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination after a structured-educational intervention. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, R.A.; Hagensee, M.E.; Fisher, R.; Stradtman, L.R.; Collins, T. Self-collected vaginal swabs for HPV screening: An exploratory study of rural Black Mississippi women. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 7, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, M.E.; Christy, S.M.; Winger, J.G.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Mosher, C.E. Self-efficacy and HPV Vaccine Attitudes Mediate the Relationship Between Social Norms and Intentions to Receive the HPV Vaccine Among College Students. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Hu, W.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, F.; Qiao, Y.; Gao, L.; Ma, W. Awareness of and willingness to be vaccinated by human papillomavirus vaccine among junior middle school students in Jinan, China. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2018, 14, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, S.; Restle, H.; Naz, A.; Tatar, O.; Shapiro, G.K.; Rosberger, Z. Parents’ involvement in the human papillomavirus vaccination decision for their sons. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2017, 14, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, T.; Shi, X.; Wu, K. Awareness and Knowledge about Human Papilloma Virus Infection among Students at Secondary Occupational Health School in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Illana, P.; Diez-Domingo, J.; Navarro-Illana, E.; Tuells, J.; Aleman, S.; Puig-Barbera, J. “Knowledge and attitudes of Spanish adolescent girls towards human papillomavirus infection: Where to intervene to improve vaccination coverage”. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, T.T.; Tam, K.F.; Lee, P.W.; Chan, K.K.; Ngan, H.Y. The effect of school-based cervical cancer education on perceptions towards human papillomavirus vaccination among Hong Kong Chinese adolescent girls. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 84, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Nie, S. Awareness and knowledge about human papillomavirus vaccination and its acceptance in China: A meta-analysis of 58 observational studies. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontos, E.Z.; Emmons, K.M.; Puleo, E.; Viswanath, K. Contribution of communication inequalities to disparities in human papillomavirus vaccine awareness and knowledge. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juneau, C.; Fall, E.; Bros, J.; Le Duc-Banaszuk, A.S.; Michel, M.; Bruel, S.; Marie Dit Asse, L.; Kalecinski, J.; Bonnay, S.; Mueller, J.E.; et al. Do boys have the same intentions to get the HPV vaccine as girls? Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions in France. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2628–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura-Morales, B.; Castellanos-Rojas, M.; Chávez Montes de Oca, V.G.; Sánchez-Valdivieso, E.A. Estrategia educativa breve para mantenimiento del conocimiento sobre el virus del papiloma humano y prevención del cáncer en adolescentes. Clín. Investig. Ginecol. Obstet. 2017, 44, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patty, N.J.S.; van Dijk, H.M.; Wallenburg, I.; Bal, R.; Helmerhorst, T.J.M.; van Exel, J.; Cramm, J.M. To vaccinate or not to vaccinate? Perspectives on HPV vaccination among girls, boys, and parents in the Netherlands: A Q-methodological study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.Y.; Koopmeiners, J.S.; McHugh, J.; Raveis, V.H.; Ahluwalia, J.S. mHealth Pilot Study: Text Messaging Intervention to Promote HPV Vaccination. Am. J. Health Behav. 2016, 40, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, H.; Siqueira, C.M.; Sousa, L.B.; Nicolau, A.I.O.; Lima, T.M.; Aquino, P.S.; Pinheiro, A.K.B. Effect of educational intervention for compliance of school adolescents with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2022, 56, e20220082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.M.; Sekikubo, M.; Biryabarema, C.; Byamugisha, J.J.; Steinberg, M.; Jeronimo, J.; Money, D.M.; Christilaw, J.; Ogilvie, G.S. Factors associated with high-risk HPV positivity in a low-resource setting in sub-Saharan Africa. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 81.e1–81.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeri, S.; Costantino, C.; D’Angelo, C.; Casuccio, N.; Ventura, G.; Vitale, F.; Pojero, F.; Casuccio, A. HPV vaccine hesitancy among parents of female adolescents: A pre-post interventional study. Public Health 2017, 150, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restivo, V.; Costantino, C.; Fazio, T.F.; Casuccio, N.; D’Angelo, C.; Vitale, F.; Casuccio, A. Factors Associated with HPV Vaccine Refusal among Young Adult Women after Ten Years of Vaccine Implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, N.L.; Biddell, C.B.; Rhodes, B.E.; Brewer, N.T. Provider communication and HPV vaccine uptake: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Prev. Med. 2021, 148, 106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulian, E.A.; Mitchell, K.R.; Stokley, S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: A systematic review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 1566–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, E.; Dergez, T.; Rebek-Nagy, G.; Szilard, I.; Kiss, I.; Ember, I.; Gocze, P.; D’Cruz, G. Effect of an educational intervention on Hungarian adolescents’ awareness, beliefs and attitudes on the prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine 2012, 30, 6824–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | 12–13 Years | 14–16 Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female n (%) | Male n (%) | Non-Binary n (%) | Female n (%) | Male n (%) | Non-Binary n (%) | ||

| Residence | Rural | 43 (23.4) | 28 (18.1) | 4 (36.4) | 63 (20.1) | 60 (20.2) | 1 (14.3) |

| Semi-urban | 35 (19.0) | 29 (18.7) | 0 (0.0) | 55 (17.6) | 42 (14.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Urban | 106 (57.6) | 98 (63.2) | 7 (63.6) | 195 (62.3) | 195 (65.7) | 6 (85.7) | |

| Self-reported sexual education | None | 11 (6.0) | 8 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 14 (4.7) | 1 (14.3) |

| Little | 65 (35.3) | 57 (36.8) | 6 (54.5) | 59 (18.8) | 44 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Enough | 97 (52.7) | 70 (45.2) | 3 (27.3) | 206 (65.8) | 187 (63.0) | 3 (42.9) | |

| A lot | 11 (6.0) | 20 (12.9) | 2 (18.2) | 46 (14.7) | 52 (17.5) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Prior Subjective knowledge about HPV * | 0 | 6 (3.3) | 10 (6.5) | 1 (9.1) | 11 (3.5) | 32 (10.8) | 1 (14.3) |

| 1 | 30 (16.3) | 24 (15.5) | 3 (27.3) | 40 (12.8) | 31 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 | 46 (25.0) | 47 (30.3) | 4 (36.4) | 74 (23.6) | 65 (21.9) | 2 (28.6) | |

| 3 | 73 (39.7) | 45 (29.0) | 1 (9.1) | 98 (31.3) | 88 (29.6) | 1 (14.3) | |

| 4 | 17 (9.2) | 18 (11.6) | 0 (0.0) | 64 (20.4) | 48 (16.2) | 2 (28.6) | |

| 5 | 12 (6.5) | 11 (7.1) | 2 (18.2) | 26 (8.3) | 33 (11.1) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Parents’ Education | Primary | 3 (1.6) | 6 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (3.8) | 21 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Secondary | 38 (20.7) | 33 (21.3) | 2 (18.2) | 111 (35.5) | 65 (21.9) | 1 (14.3) | |

| University | 66 (35.9) | 60 (38.7) | 3 (27.3) | 101 (32.3) | 106 (35.7) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Unknown | 77 (41.8) | 56 (36.1) | 6 (54.5) | 89 (28.4) | 105 (35.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

| HPV Vaccination | Yes | 116 (63.0) | 74 (47.7) | 6 (54.5) | 237 (75.7) | 89 (30.0) | 2 (28.6) |

| No | 38 (20.7) | 32 (20.6) | 1 (9.1) | 18 (5.8) | 116 (39.1) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Not reported | 30 (16.3) | 49 (31.6) | 4 (36.4) | 58 (18.5) | 92 (31.0) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Vaccination Status | Gender | n | Baseline Hit Rate (% ± SD) | Post-Intervention Hit Rate (% ± SD) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | Improvement in Hit Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated | Female | 353 | 62.9 ± 18.0 | 91.4 ± 9.6 | 26.7 to 30.3 | <0.001 | 28.5 ± 16.9 |

| Male | 163 | 58.0 ± 19.1 | 86.4 ± 14.4 | 25.4 to 31.4 | <0.001 | 28.4 ± 19.1 | |

| Non-binary | 8 | 50.8 ± 25.5 | 71.1 ± 34.9 | 2.3 to 38.4 | 0.032 | 20.3 ± 21.6 | |

| Non-Vaccinated | Female | 144 | 53.6 ± 20.5 | 86.7 ± 12.2 | 29.9 to 36.2 | <0.001 | 33.1 ± 19.2 |

| Male | 289 | 51.5 ± 22.7 | 83.3 ± 20.9 | 29.2 to 34.3 | <0.001 | 31.7 ± 22.0 | |

| Non-binary | 10 | 43.8 ± 28.0 | 73.1 ± 27.2 | 5.1 to 53.7 | 0.023 | 29.4 ± 34.0 | |

| Vaccination Status | Age Group | n | Baseline Hit Rate (% ± SD) | Post-Intervention Hit Rate (% ± SD) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | Improvement in Hit Rate (%) |

| Vaccinated | 12–13 | 196 | 56.3 ± 18.6 | 88.2 ± 12.4 | 29.3 to 34.6 | <0.001 | 32.0 ± 18.9 a |

| 14–16 | 328 | 64.2 ± 18.0 | 90.4 ± 12.4 | 24.4 to 27.9 | <0.001 | 26.2 ± 16.5 a | |

| Total | 524 | 61.2 ± 18.6 | 89.6 ± 12.4 | 26.8 to 29.8 | <0.001 | 28.3 ± 17.7 c | |

| Non vaccinated | 12–13 | 154 | 48.6 ± 20.9 | 83.8 ± 16.1 | 24.4 to 27.9 | <0.001 | 35.2 ± 22.3 b |

| 14–16 | 289 | 53.9 ± 22.6 | 84.3 ± 0.1 | 28.1 to 32.9 | <0.001 | 30.5 ± 20.8 b | |

| Total | 443 | 52.0 ± 22.1 | 84.1 ± 18.8 | 30.1 to 34.1 | <0.001 | 32.1 ± 21.4 c | |

| Global Total | 967 | 57.1 ± 20.8 | 87.1 ± 15.9 | 28.8 to 31.3 | <0.001 | 30.1 ± 19.5 |

| Vaccination Status | Gender | Questionnaire Moment | Willingness to Vaccinate | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Uncertain | ||||

| Vaccinated | Female | Pre-intervention | 324 (91.7%) | 3 (0.8%) | 26 (7.4%) | 353 |

| Post-intervention | 348 (98.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.4%) | 353 | ||

| Male | Pre-intervention | 139 (85.3%) | 4 (2.5%) | 20 (12.3%) | 163 | |

| Post-intervention | 155 (95.1%) | 3 (1.8%) | 5 (3.1%) | 163 | ||

| Non-binary | Pre-intervention | 7 (22.5%) | 4 (12.9%) | 20 (64.5%) | 31 | |

| Post-intervention | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (23.1%) | 5 (38.5%) | 13 | ||

| Non-Vaccinated | Female | Pre-intervention | 112 (77.8%) | 2 (1.4%) | 30 (20.8%) | 144 |

| Post-intervention | 136 (94.4%) | 3 (2.1%) | 5 (3.5%) | 144 | ||

| Male | Pre-intervention | 187 (64.7%) | 22 (7.6%) | 80 (27.7%) | 289 | |

| Post-intervention | 248 (85.8%) | 18 (6.2%) | 23 (8.0%) | 289 | ||

| Non-binary | Pre-intervention | 4 (40.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 10 | |

| Post-intervention | 5 (50.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 10 | ||

| Vaccination Status | Age Group | Phase | Willingness to Vaccinate | Total | ||

| Yes | No | Uncertain | ||||

| Vaccinated | 12–13 years | Pre-intervention | 172 (87.8%) | 2 (1.0%) | 22 (11.2%) | 196 |

| Post-intervention | 189 (96.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (3.6%) | 196 | ||

| 14–16 years | Pre-intervention | 298 (90.9%) | 5 (1.5%) | 25 (7.6%) | 328 | |

| Post-intervention | 319 (97.3%) | 4 (1.2%) | 5 (1.5%) | 328 | ||

| Non vaccinated | 12–13 years | Pre-intervention | 110 (71.4%) a | 5 (3.2%) | 39 (25.3%) | 154 |

| Post-intervention | 142 (92.2%) a,c | 5 (3.2%) | 7 (4.5%) | 154 | ||

| 14–16 years | Pre-intervention | 193 (66.8%) b | 22 (7.6%) | 74 (25.6%) | 289 | |

| Post-intervention | 247 (85.5%) b,c | 17 (5.9%) | 25 (8.7%) | 289 | ||

| Global Total | 967 | Pre-intervention | 773 (79.9%) d | 34 (3.5%) | 160 (16.5%) | 967 |

| Post-intervention | 897 (92.8%) d | 26 (2.7%) | 44 (4.6%) | 967 | ||

| Phase | Variable | B | SE | Wald | df | p | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Intervention | Highly effective vaccine | 0.972 | 0.464 | 4.388 | 1 | 0.036 | 2.644 | [1.065, 6.567] |

| 6–11 hits | 1.461 | 0.315 | 21.528 | 1 | <0.001 | 4.309 | [2.325, 7.985] | |

| ≥12 hits | 1.479 | 0.405 | 13.362 | 1 | <0.001 | 4.389 | [1.986, 9.702] | |

| Constant | −2.211 | 1.094 | 4.086 | 1 | 0.043 | 0.110 | ||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow test: χ2= 4.218, df 8, p = 0.837; R2 = 0.279. Specificity: 92.1%; Sensibility: 40.0%; Forecast Accuracy: 75.6% | ||||||||

| Post-Intervention | Female gender | 3.123 | 1.034 | 9.121 | 1 | 0.003 | 22.724 | [2.993, 172.510] |

| Male gender | 2.158 | 0.951 | 5.144 | 1 | 0.023 | 8.653 | [1.341, 55.857] | |

| 14–16 years old | −1.189 | 0.544 | 4.775 | 1 | 0.029 | 0.304 | [0.105, 0.885] | |

| Sexual information: teachers | 1.678 | 0.758 | 4.898 | 1 | 0.027 | 5.356 | [1.212, 23.676] | |

| Sexual information: parents | 1.782 | 0.765 | 5.435 | 1 | 0.020 | 5.944 | [1.328, 26.599] | |

| Constant | −2.908 | 1.520 | 3.659 | 1 | 0.056 | 0.055 | ||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow test: χ2= 7.535, df 8, p = 0.480; R2 = 0.452. Specificity: 98.6%; Sensibility: 44.4%; Forecast Accuracy: 92.7% | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

González-Veiga, E.J.; González-Palanca, S.; Palmeiro-Fernández, G.; Domínguez-Salgado, J.C.; Rubio-Cid, P.; López-Pais, M.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Daley, E.M.; Lorenzo-Pouso, A.I. A Community-Based Intervention in Middle Schools in Spain to Improve HPV Vaccination Acceptance: A “Pill of Knowledge” Approach. Vaccines 2026, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010022

González-Veiga EJ, González-Palanca S, Palmeiro-Fernández G, Domínguez-Salgado JC, Rubio-Cid P, López-Pais M, Caponio VCA, Daley EM, Lorenzo-Pouso AI. A Community-Based Intervention in Middle Schools in Spain to Improve HPV Vaccination Acceptance: A “Pill of Knowledge” Approach. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Veiga, Ernesto J., Sergio González-Palanca, Gerardo Palmeiro-Fernández, Juan C. Domínguez-Salgado, Paula Rubio-Cid, María López-Pais, Vito Carlo Alberto Caponio, Ellen M. Daley, and Alejandro I. Lorenzo-Pouso. 2026. "A Community-Based Intervention in Middle Schools in Spain to Improve HPV Vaccination Acceptance: A “Pill of Knowledge” Approach" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010022

APA StyleGonzález-Veiga, E. J., González-Palanca, S., Palmeiro-Fernández, G., Domínguez-Salgado, J. C., Rubio-Cid, P., López-Pais, M., Caponio, V. C. A., Daley, E. M., & Lorenzo-Pouso, A. I. (2026). A Community-Based Intervention in Middle Schools in Spain to Improve HPV Vaccination Acceptance: A “Pill of Knowledge” Approach. Vaccines, 14(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010022