Bridging the Gap: Two Decades of Childhood Vaccination Coverage and Equity in Cambodia and the Philippines (2000–2022)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Outcome Measures

2.2. Explanatory Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Routine Childhood Vaccination Coverage on Schedule

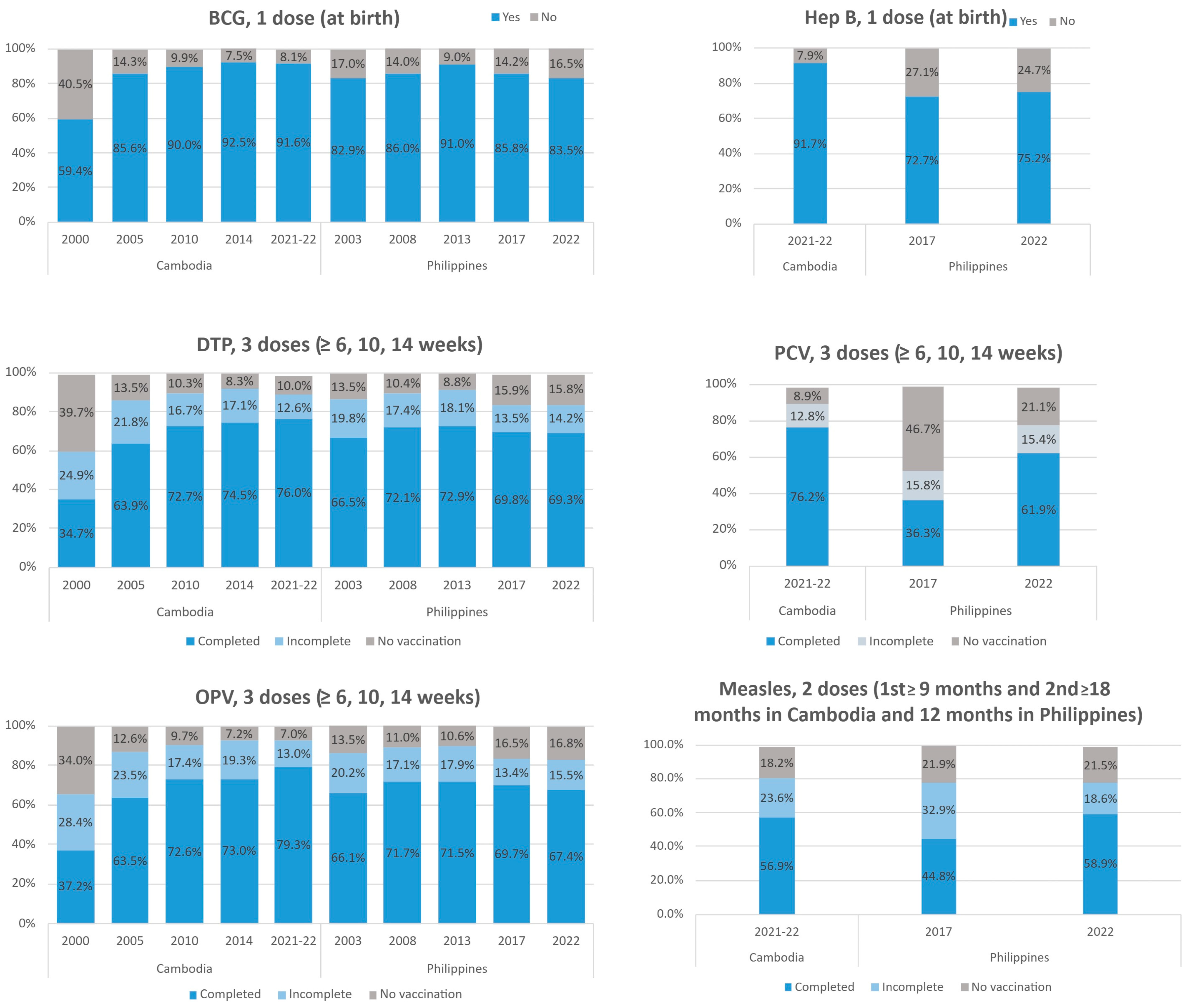

3.3. BCG and Hepatitis B (Single-Dose at Birth)

3.4. DTP, OPV, and PCV (Three Doses at 6, 10, and 14 Weeks)

3.5. Measles (Two Doses at 9 and 12/18 Months)

3.6. Disparity Between Urban and Rural Areas and by Wealth Groups

3.7. Determinants of Completing Vaccine Administration on Schedule

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shattock, A.J.; Johnson, H.C.; Sim, S.Y.; Carter, A.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.C.W.; Thompson, K.M.; Badizadegan, K.; Lambert, B.; Ferrari, M.J.; et al. Contribution of vaccination to improved survival and health: Modelling 50 years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet 2024, 403, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Table 1: Summary of WHO Position Papers—Recommendations for Routine Immunization. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/table1-summary-of-who-position-papers-recommendations-for-routine-immunization (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Haeuser, E.; Byrne, S.; Nguyen, J.; Raggi, C.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Bisignano, C.; Harris, A.A.; Smith, A.E.; Lindstedt, P.A.; Smith, G.; et al. Global, regional, and national trends in routine childhood vaccination coverage from 1980 to 2023 with forecasts to 2030: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.A.; Hartner, A.-M.; Echeverria-Londono, S.; Roth, J.; Li, X.; Abbas, K.; Portnoy, A.; Vynnycky, E.; Woodruff, K.; Ferguson, N.M.; et al. Vaccine equity in low and middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Comparative Analysis of National Immunization Programs in Select ASEAN and SAARC Countries: Progress and Challenges; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Global Health Progress. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Available online: https://globalhealthprogress.org/collaboration/gavi-the-vaccine-alliance/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- IA2030. Access to Immunization in Middle-Income Countries: Immunization Agenda 2030—In-Depth Review. Available online: https://www.immunizationagenda2030.org/images/documents/IA2030_MICBrief_5May.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Gavi. Eligibility Policy. 2025. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/types-support/sustainability/eligibility (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Outbreak Response Stops Measles Making a Come-Back in Cambodia. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/newsroom/feature-stories/item/outbreak-response-stops-measles-making-a-come-back-in-cambodia (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Domai, F.M.; Agrupis, K.A.; Han, S.M.; Sayo, A.R.; Ramirez, J.S.; Nepomuceno, R.; Suzuki, S.; Villanueva, A.M.G.; Salva, E.P.; Villarama, J.B.; et al. Measles outbreak in the Philippines: Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of hospitalized children, 2016–2019. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac. 2022, 19, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The DHS Program. Access Instructions. Available online: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/Access-Instructions.cfm (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- National Institute of Statistics (NIS) [Cambodia], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Cambodia], and ICF. Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2021–2022 Final Report; NIS, MoH, and ICF: Phnom Penh, Cambodia; Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) and ICF. 2022 Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS): Final Report; PSA and ICF: Quezon City, Philippines; Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The DHS Program. Wealth Index Construction. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/topics/wealth-index/Wealth-Index-Construction.cfm (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Schlotheuber, A.; Hosseinpoor, A.R. Summary Measures of Health Inequality: A Review of Existing Measures and Their Application. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Project. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Soeung, S.C.; Grundy, J.; Ly, C.K.; Samnang, C.; Boreland, M.; Brooks, A.; Maynard, J.; Biggs, B.A. Improving Immunization Coverage through Budgeted Microplans and Sub-national Performance Agreements: Early Experience from Cambodia. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2006, 18, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaupart, P.; Dipple, L.; Dercon, S. Has Gavi lived up to its promise? Quasi-experimental evidence on country immunisation rates and child mortality. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Mak, J.; de Broucker, G.; Patenaude, B. Multivariate Assessment of Vaccine Equity in Cambodia: A Longitudinal VERSE Tool Case Study Using Demographic and Health Survey 2004, 2010, and 2014. Vaccines 2023, 11, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Government-Sponsored Cash Transfer Scheme to Benefit Poor Women and Children and Improve Access to Health Services; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Khuon, D.; Saphonn, V.; Jia, P.; Long, Q. Two Decades of Change in Childbirth Care in Cambodia (2000–2021): Disparities in Ceasarean Section Utilization Between Public and Private Facilities. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2025, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, M.; Dee, E.C.; Ho, B.L. Vaccination in the Philippines: Experiences from history and lessons for the future. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2021, 17, 1873–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabale, M.A.A.; Tejero, L.M.S.; Montes, L.A.; Collante, M.T.M.; Tempongko, M.S.B.; Tolabing, M.C.C. Implications of information heard about Dengvaxia on Filipinos’ perception on vaccination. Vaccine 2024, 42, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, V.G.; Lasco, G.; David, C.C. Fear, mistrust, and vaccine hesitancy: Narratives of the dengue vaccine controversy in the Philippines. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4964–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hapal, K. The Philippines’ COVID-19 Response: Securitising the Pandemic and Disciplining the Pasaway. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 2021, 40, 186810342199426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducanes, G.M.; Daway-Ducanes, S.L.S. Covid Lockdown and Employment in the Philippines. J. Dev. Stud. 2024, 60, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. New Data Indicates Declining Confidence in Childhood Vaccines of up to 25 Percentage Points in the Philippines During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/philippines/press-releases/new-data-indicates-declining-confidence-childhood-vaccines-25-percentage-points (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Gavi. Gavi MICs Approach—Considerations on Access to Sustainable Supply and Affordable Pricing. 2024. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/types-support/sustainability/gavi-mics-approach/considerations-access-sustainable-supply-affordable-pricing (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Perdrizet, J.; Horn, E.K.; Nua, W.; Perez-Peralta, J.; Nailes, J.; Santos, J.; Ong-Lim, A. Cost-Effectiveness of the 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV13) Versus Lower-Valent Alternatives in Filipino Infants. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021, 10, 2625–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, J.; Dashpagma, O.; Vichit, O.; Chham, S.; Demberelsuren, S.; Grabovac, V.; Hossain, S.; Iijima, M.; Lee, C.W.; Purevdagva, A.; et al. Challenges for Sustaining Measles Elimination: Post-Verification Large-Scale Import-Related Measles Outbreaks in Mongolia and Cambodia, Resulting in the Loss of Measles Elimination Status. Vaccines 2024, 12, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccher, S.; Laman, M.; Danchin, M.; Angrisano, F.; Morgan, C. Missed Measles Immunisations Places Individuals and Communities at Risk: The Equity Argument for Including Measles in Under-Immunised Definitions. Vaccines 2025, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utazi, C.E.; Thorley, J.; Alegana, V.A.; Ferrari, M.J.; Takahashi, S.; Metcalf, C.J.E.; Lessler, J.; Cutts, F.T.; Tatem, A.J. Mapping vaccination coverage to explore the effects of delivery mechanisms and inform vaccination strategies. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajizadeh, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in child vaccination in low/middle-income countries: What accounts for the differences? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisson-Walsh, A.; Thompson, P.; Fried, B.; Shea, C.M.; Ngimbi, P.; Lumande, F.; Tabala, M.; Kashamuka, M.M.; Babakazo, P.; Domino, M.E.; et al. Childhood immunization uptake determinants in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Ordered regressions to assess timely infant vaccines administered at birth and 6-weeks. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (a) Cambodia | ||||||

| Characteristics | 2000 (n = 2978) | 2005 (n = 3123) | 2010 (n = 3097) | 2014 (n = 2841) | 2021–2022 (n = 3348) | p-Value |

| Place of residence 1 | <0.001 | |||||

| Urban | 411 (13.8%) | 643 (20.6%) | 805 (26.0%) | 772 (27.2%) | 1099 (32.8%) | |

| Rural | 2559 (85.9%) | 2439 (78.1%) | 2252 (72.7%) | 2029 (71.4%) | 2222 (66.4%) | |

| Maternal age | <0.001 | |||||

| <19 | 249 (8.4%) | 245 (7.8%) | 262 (8.5%) | 268 (9.4%) | 270 (8.1%) | |

| 20–29 | 1379 (46.3%) | 1723 (55.2%) | 1969 (63.6%) | 1762 (62.0%) | 1783 (53.3%) | |

| 30+ | 1350 (45.3%) | 1155 (37.0%) | 866 (28.0%) | 811 (28.5%) | 1295 (38.7%) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||||

| No education | 1089 (36.6%) | 848 (27.2%) | 608 (19.6%) | 360 (12.7%) | 401 (12.0%) | |

| Incomplete primary | 1378 (46.3%) | 1604 (51.4%) | 1343 (43.4%) | 1060 (37.3%) | 994 (29.7%) | |

| Primary | 493 (16.6%) | 616 (19.7%) | 988 (31.9%) | 1147 (40.4%) | 1502 (44.9%) | |

| Secondary and higher | 18 (0.6%) | 55 (1.8%) | 158 (5.1%) | 274 (9.6%) | 451 (13.5%) | |

| Wealth index | <0.001 | |||||

| Poorest | - | 873 (28.0%) | 780 (25.2%) | 659 (23.2%) | 964 (28.8%) | |

| Poorer | - | 715 (22.9%) | 581 (18.8%) | 528 (18.6%) | 658 (19.7%) | |

| Middle | - | 593 (19.0%) | 520 (16.8%) | 441 (15.5%) | 611 (18.2%) | |

| Richer | - | 475 (15.2%) | 572 (18.5%) | 506 (17.8%) | 672 (20.1%) | |

| Richest | - | 467 (15.0%) | 644 (20.8%) | 707 (24.9%) | 443 (13.2%) | |

| Employment 2 | <0.001 | |||||

| Did not work | 636 (21.4%) | 11 (0.4%) | 747 (24.1%) | 877 (30.9%) | 1075 (32.1%) | |

| Worked | 2335 (78.4%) | 2347 (72.9%) | 2347 (75.8%) | 1953 (68.7%) | 2159 (64.5%) | |

| Parity | <0.001 | |||||

| 1 | 541 (18.2%) | 861 (27.6%) | 1104 (35.6%) | 1163 (40.9%) | 1099 (32.8%) | |

| 2 | 541 (18.2%) | 710 (22.7%) | 837 (27.0%) | 866 (30.5%) | 1216 (36.3%) | |

| 3+ | 1896 (63.7%) | 1552 (49.7%) | 1156 (37.3%) | 812 (28.6%) | 1033 (30.9%) | |

| Number of children eligible for vaccines on schedule | ||||||

| One-dose vaccine, at birth | 2978 | 3123 | 3097 | 2841 | 3348 | |

| Three-dose vaccines, ≥14 weeks | 2569 | 2742 | 2776 | 2518 | 2926 | |

| Two-dose vaccines, ≥18 months | - | - | - | - | 802 | |

| (b) The Philippines | ||||||

| Characteristics | 2003 (n = 2592) | 2008 (n = 2443) | 2013 (n = 2718) | 2017 (n = 3809) | 2022 (n = 3000) | p-Value |

| Place of residence 3 | <0.001 | |||||

| Urban | 1190 (45.9%) | 1016 (41.6%) | 1101 (40.5%) | 1218 (32.0%) | 1059 (35.3%) | |

| Rural | 1345 (51.9%) | 1353 (55.4%) | 1536 (56.5%) | 2540 (66.7%) | 1873 (62.4%) | |

| Maternal age | <0.001 | |||||

| <19 | 182 (7.0%) | 221 (9.0%) | 282 (10.4%) | 365 (9.6%) | 250 (8.3%) | |

| 20 –29 | 1397 (53.9%) | 1288 (52.7%) | 1377 (50.7%) | 2012 (52.8%) | 1450 (48.3%) | |

| 30 + | 1013 (39.1%) | 934 (38.2%) | 1059 (39.0%) | 1432 (37.6%) | 1300 (43.3%) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||||

| No education | 57 (2.2%) | 43 (1.8%) | 47 (1.7%) | 65 (1.7%) | 41 (1.4%) | |

| Incomplete primary | 355 (13.7%) | 276 (11.3%) | 289 (10.6%) | 391 (10.3%) | 189 (6.3%) | |

| Primary | 834 (32.2%) | 745 (30.5%) | 748 (27.5%) | 1010 (26.5%) | 881 (29.4%) | |

| Secondary and higher | 1346 (51.9%) | 1379 (56.4%) | 1634 (60.1%) | 2343 (61.5%) | 1889 (63.0%) | |

| Wealth index | <0.001 | |||||

| Poorest | 745 (28.7%) | 704 (28.8%) | 800 (29.4%) | 1339 (35.2%) | 1074 (35.8%) | |

| Poorer | 595 (23.0%) | 589 (24.1%) | 607 (22.3%) | 903 (23.7%) | 634 (21.1%) | |

| Middle | 493 (19.0%) | 444 (18.2%) | 559 (20.6%) | 669 (17.6%) | 542 (18.1%) | |

| Richer | 429 (16.6%) | 417 (17.1%) | 429 (15.8%) | 531 (13.9%) | 391 (13.0%) | |

| Richest | 330 (12.7%) | 289 (11.8%) | 323 (11.9%) | 367 (9.6%) | 359 (12.0%) | |

| Employment 4 | 0.097 | |||||

| Did not work | 1558 (60.1%) | 1381 (56.5%) | 1573 (57.9%) | 2322 (61.0%) | 1812 (60.4%) | |

| Worked | 1025 (39.5%) | 976 (40.0%) | 1029 (37.9%) | 1414 (37.1%) | 1178 (39.3%) | |

| Parity | <0.001 | |||||

| 1 | 720 (27.8%) | 710 (29.1%) | 821 (30.2%) | 1120 (29.4%) | 944 (31.5%) | |

| 2 | 587 (22.6%) | 536 (21.9%) | 668 (24.6%) | 978 (25.7%) | 741 (24.7%) | |

| 3+ | 1285 (49.6%) | 1197 (49.0%) | 1229 (45.2%) | 1711 (44.9%) | 1315 (43.8%) | |

| Number of children eligible for vaccines on schedule | ||||||

| One-dose vaccine, at birth | 2592 | 2443 | 2718 | 3809 | 3000 | |

| Three-dose vaccines, ≥14 weeks | 2297 | 2163 | 2415 | 3333 | 2677 | |

| Two-dose vaccines, ≥12 months | - | - | - | 1840 | 1473 | |

| (a) Cambodia | ||||||

| DTP | PCV | Measles | ||||

| Variables | Adjusted 1 OR (95%CI) | p-Value | Adjusted 1 OR (95%CI) | p-Value | Adjusted 1 OR (95%CI) | p-Value |

| Maternal age | ||||||

| <19 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 20–29 | 1.76 (1.25, 2.49) | 0.001 | 1.73 (1.22, 2.46) | 0.002 | 1.02 (0.55, 1.89) | 0.9 |

| 30+ | 2.46 (1.65, 3.67) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.34, 3.01) | <0.001 | 1.39 (0.69, 2.78) | 0.4 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Urban | 1.01 (0.80, 1.26) | 1.0 | 1.02 (0.81, 1.28) | 0.9 | 0.95 (0.67, 1.35) | 0.8 |

| Education | ||||||

| No education | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Incomplete primary | 1.68 (1.27, 2.21) | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.12, 1.96) | 0.006 | 1.99 (1.20, 3.32) | 0.008 |

| Primary | 2.03 (1.52, 2.70) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.37, 2.45) | <0.001 | 2.36 (1.43, 3.94) | <0.001 |

| Secondary and higher | 2.44 (1.61, 3.73) | <0.001 | 2.64 (1.71, 4.13) | <0.001 | 3.42 (1.75, 6.79) | <0.001 |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Poorer | 1.46 (1.12, 1.91) | 0.005 | 1.39 (1.07, 1.82) | 0.02 | 1.29 (0.83, 2.00) | 0.3 |

| Middle | 1.50 (1.13, 1.98) | 0.005 | 1.20 (0.91, 1.58) | 0.2 | 1.19 (0.74, 1.91) | 0.5 |

| Richer | 1.98 (1.46, 2.70) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.43, 2.68) | <0.001 | 1.31 (0.81, 2.11) | 0.3 |

| Richest | 1.63 (1.13, 2.38) | 0.01 | 1.64 (1.12, 2.42) | 0.01 | 1.68 (0.95, 3.01) | 0.08 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Did not work | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Worked | 1.02 (0.84, 1.23) | 0.9 | 0.98 (0.80, 1.19) | 0.8 | 0.80 (0.57, 1.12) | 0.2 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 3+ | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2 | 1.35 (1.06, 1.72) | 0.01 | 1.31 (1.03, 1.67) | 0.03 | 1.55 (1.04, 2.30) | 0.03 |

| 1 | 1.67 (1.25, 2.24) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.15, 2.08) | 0.004 | 1.88 (1.18, 3.02) | 0.008 |

| (b) The Philippines | ||||||

| DTP | PCV | Measles | ||||

| Variables | Adjusted 1 OR (95%CI) | p-Value | Adjusted 1 OR (95%CI) | p-Value | Adjusted 1 OR (95%CI) | p-Value |

| Maternal age | ||||||

| <19 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 20–29 | 0.97 (0.67, 1.38) | 0.9 | 0.95 (0.68, 1.33) | 0.8 | 1.26 (0.79, 2.01) | 0.3 |

| 30+ | 1.03 (0.69, 1.53) | 0.9 | 1.05 (0.72, 1.53) | 0.8 | 1.40 (0.84, 2.32) | 0.2 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Urban | 0.89 (0.73, 1.08) | 0.2 | 0.90 (0.75, 1.08) | 0.3 | 0.85 (0.67, 1.09) | 0.2 |

| Education | ||||||

| No education | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Incomplete primary | 1.70 (0.80, 3.84) | 0.2 | 1.22 (0.55, 2.95) | 0.6 | 1.21 (0.47, 3.44) | 0.7 |

| Primary | 3.12 (1.53, 6.79) | 0.003 | 2.73 (1.29, 6.32) | 0.01 | 2.33 (0.97, 6.22) | 0.07 |

| Secondary and higher | 3.93 (1.92, 8.54) | <0.001 | 3.93 (1.85, 9.08) | <0.001 | 2.89 (1.20, 7.70) | 0.02 |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Poorer | 1.67 (1.32, 2.13) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.20, 1.92) | <0.001 | 1.91 (1.40, 2.62) | <0.001 |

| Middle | 2.46 (1.86, 3.26) | <0.001 | 2.09 (1.61, 2.72) | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.24, 2.43) | 0.001 |

| Richer | 2.36 (1.71, 3.31) | <0.001 | 1.99 (1.47, 2.72) | <0.001 | 2.05 (1.38, 3.08) | <0.001 |

| Richest | 2.59 (1.81, 3.74) | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.31, 2.52) | <0.001 | 2.24 (1.46, 3.46) | <0.001 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Did not work | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Worked | 1.36 (1.12, 1.65) | 0.002 | 1.27 (1.06, 1.52) | 0.01 | 1.13 (0.90, 1.43) | 0.3 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 3+ | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2 | 1.31 (1.03, 1.67) | 0.03 | 1.26 (1.00, 1.58) | 0.048 | 1.14 (0.85, 1.53) | 0.4 |

| 1 | 1.24 (0.97, 1.61) | 0.09 | 1.30 (1.02, 1.66) | 0.03 | 1.46 (1.06, 2.02) | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Long, Q. Bridging the Gap: Two Decades of Childhood Vaccination Coverage and Equity in Cambodia and the Philippines (2000–2022). Vaccines 2025, 13, 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13090907

Zhang Y, Zhang X, Long Q. Bridging the Gap: Two Decades of Childhood Vaccination Coverage and Equity in Cambodia and the Philippines (2000–2022). Vaccines. 2025; 13(9):907. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13090907

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yanqin, Xinyu Zhang, and Qian Long. 2025. "Bridging the Gap: Two Decades of Childhood Vaccination Coverage and Equity in Cambodia and the Philippines (2000–2022)" Vaccines 13, no. 9: 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13090907

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, X., & Long, Q. (2025). Bridging the Gap: Two Decades of Childhood Vaccination Coverage and Equity in Cambodia and the Philippines (2000–2022). Vaccines, 13(9), 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13090907