Putting the Polio Workforce to Work in a Public Health Crisis: Contributions of the National Stop Transmission of Polio (NSTOP) Program to the COVID-19 Response in Pakistan

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. NSTOP Program Description

1.2. NSTOP Officer Participation in COVID-19 Response

2. Methods

3. Results

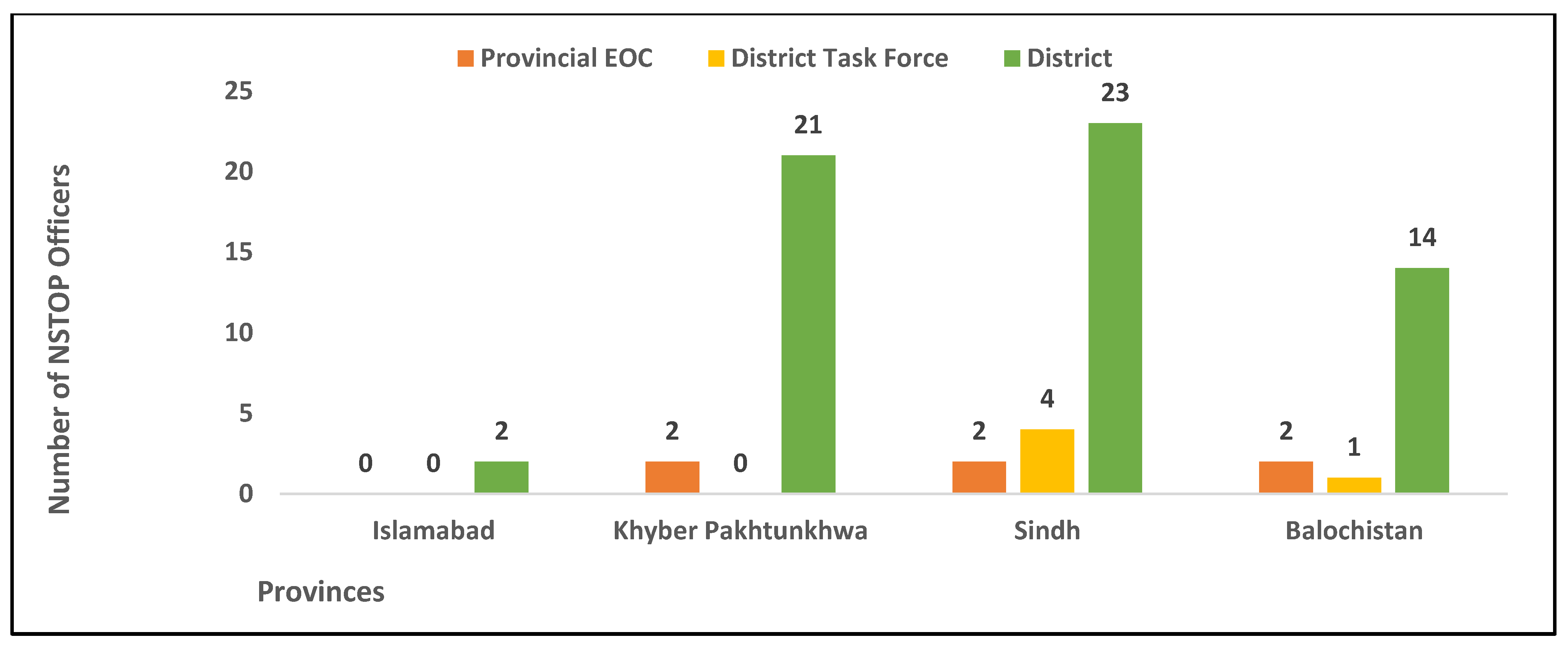

3.1. Response Coordination

3.2. Detection and Management of COVID-19 Cases

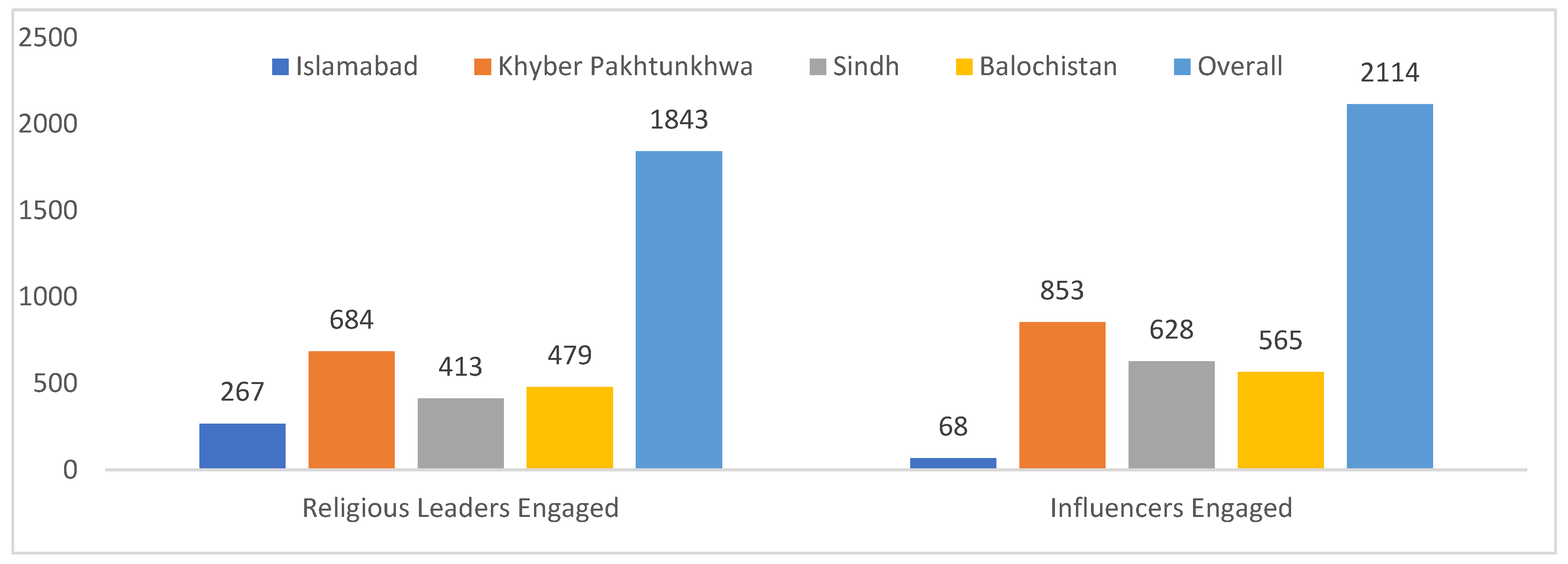

3.3. Risk Communication and Community Engagement

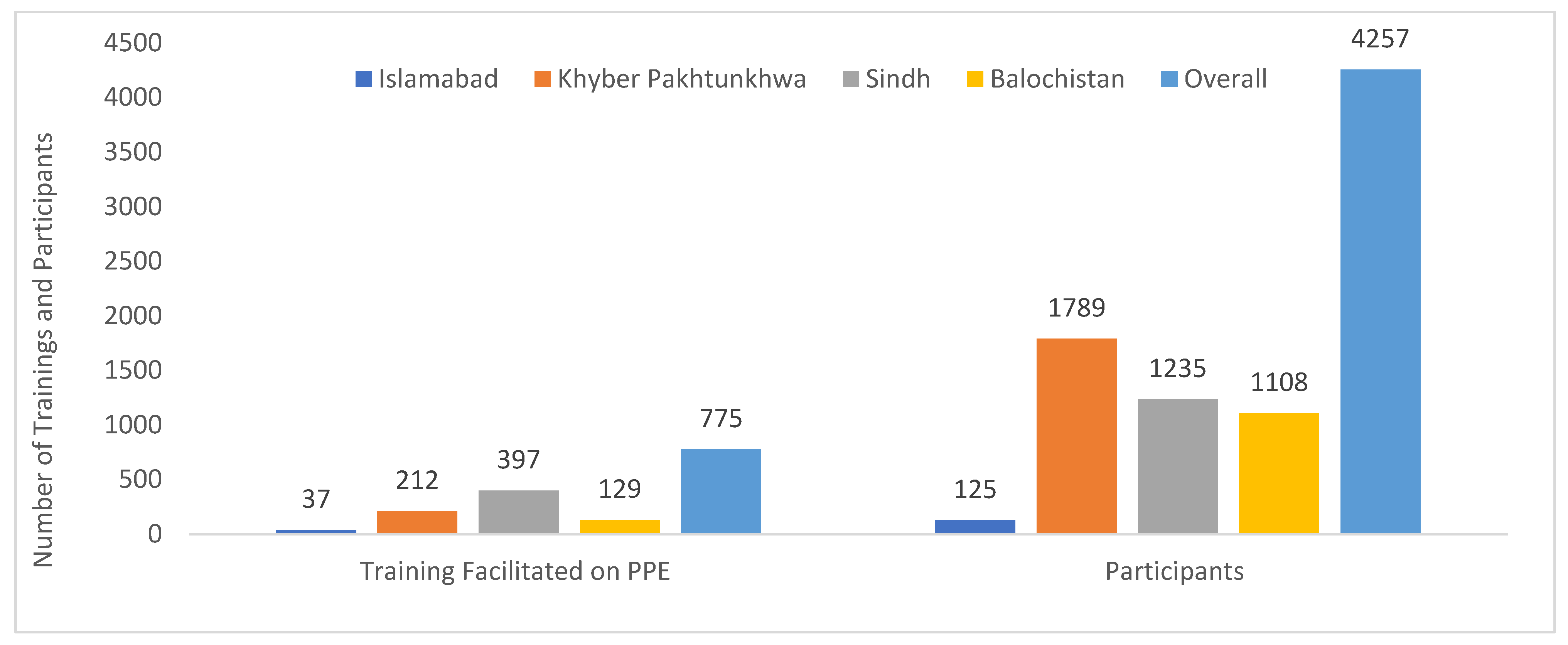

3.4. Training and Orientation Sessions

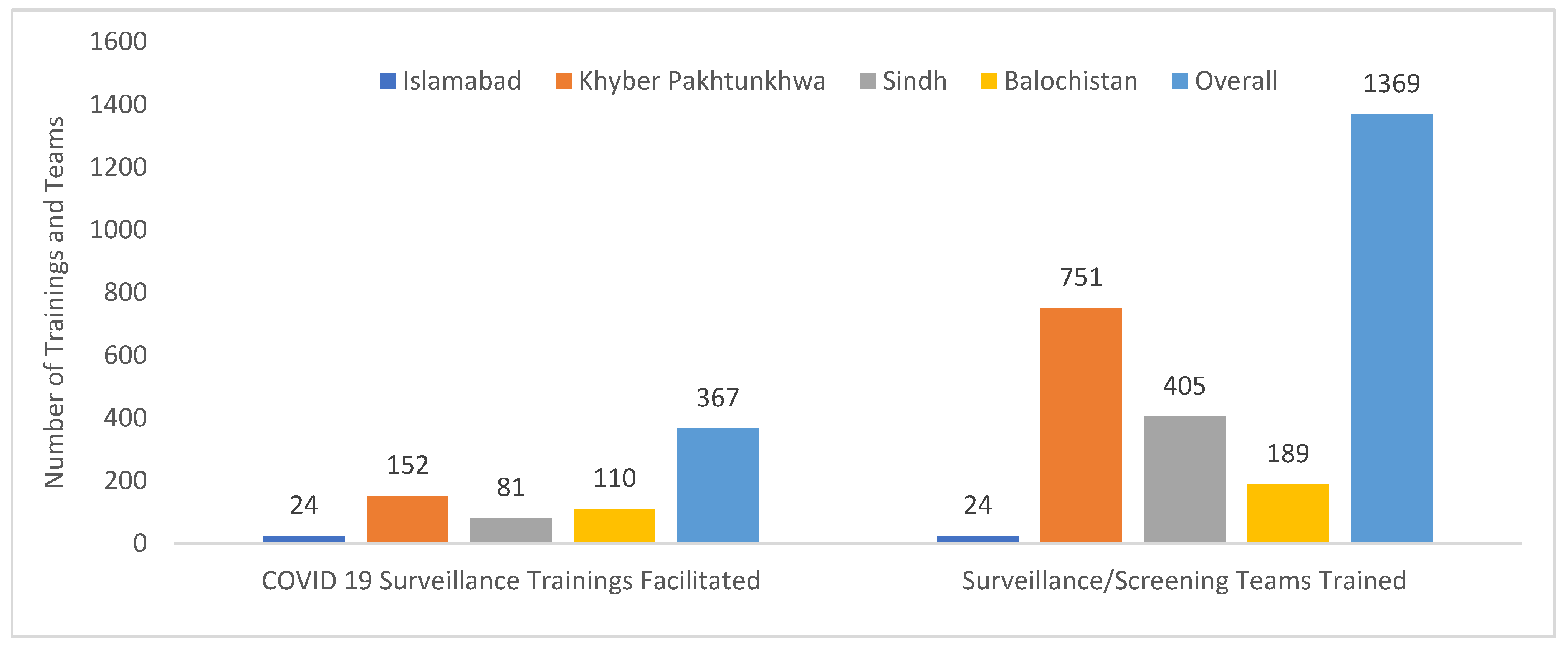

3.5. COVID-19 Surveillance Activities

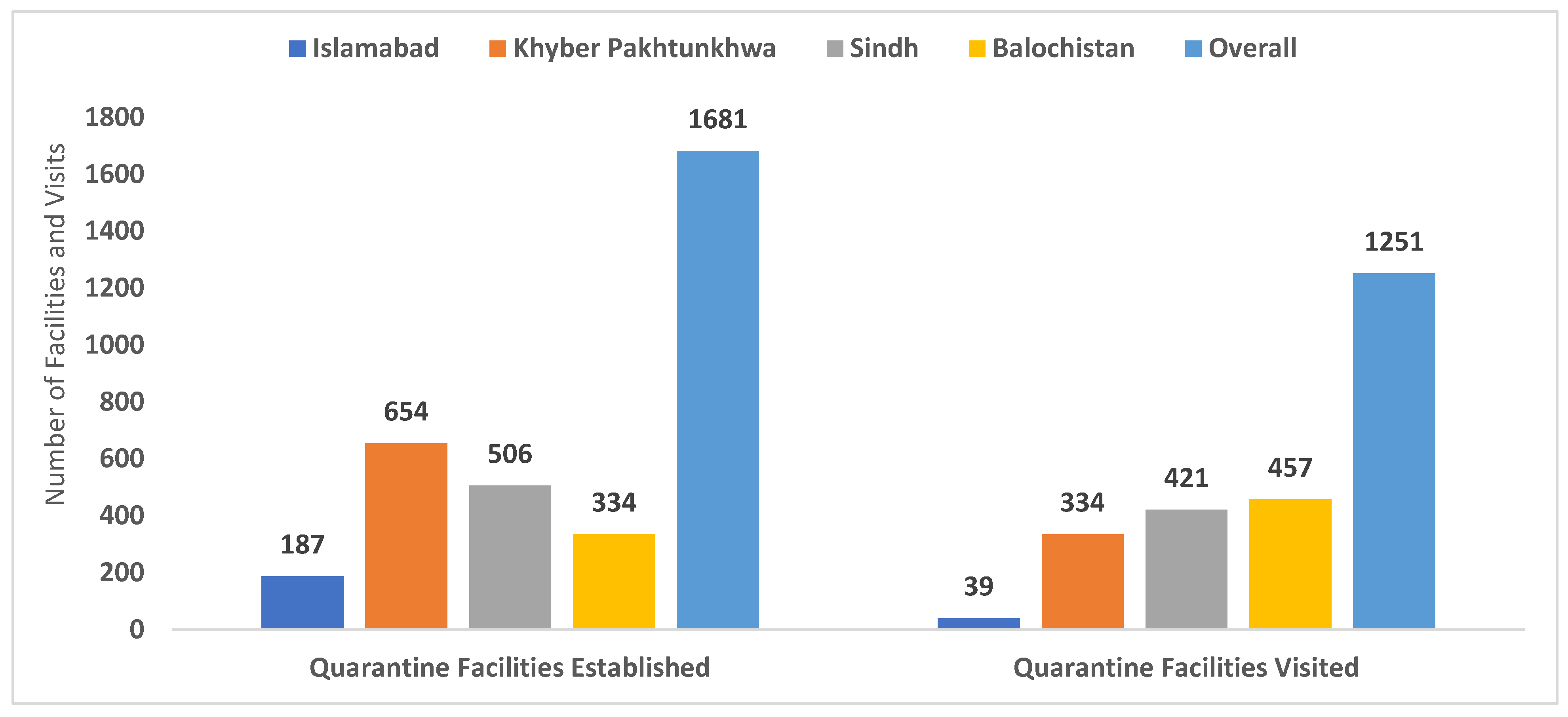

3.6. Establishment and Maintenance of Quarantine and Isolation Facilities

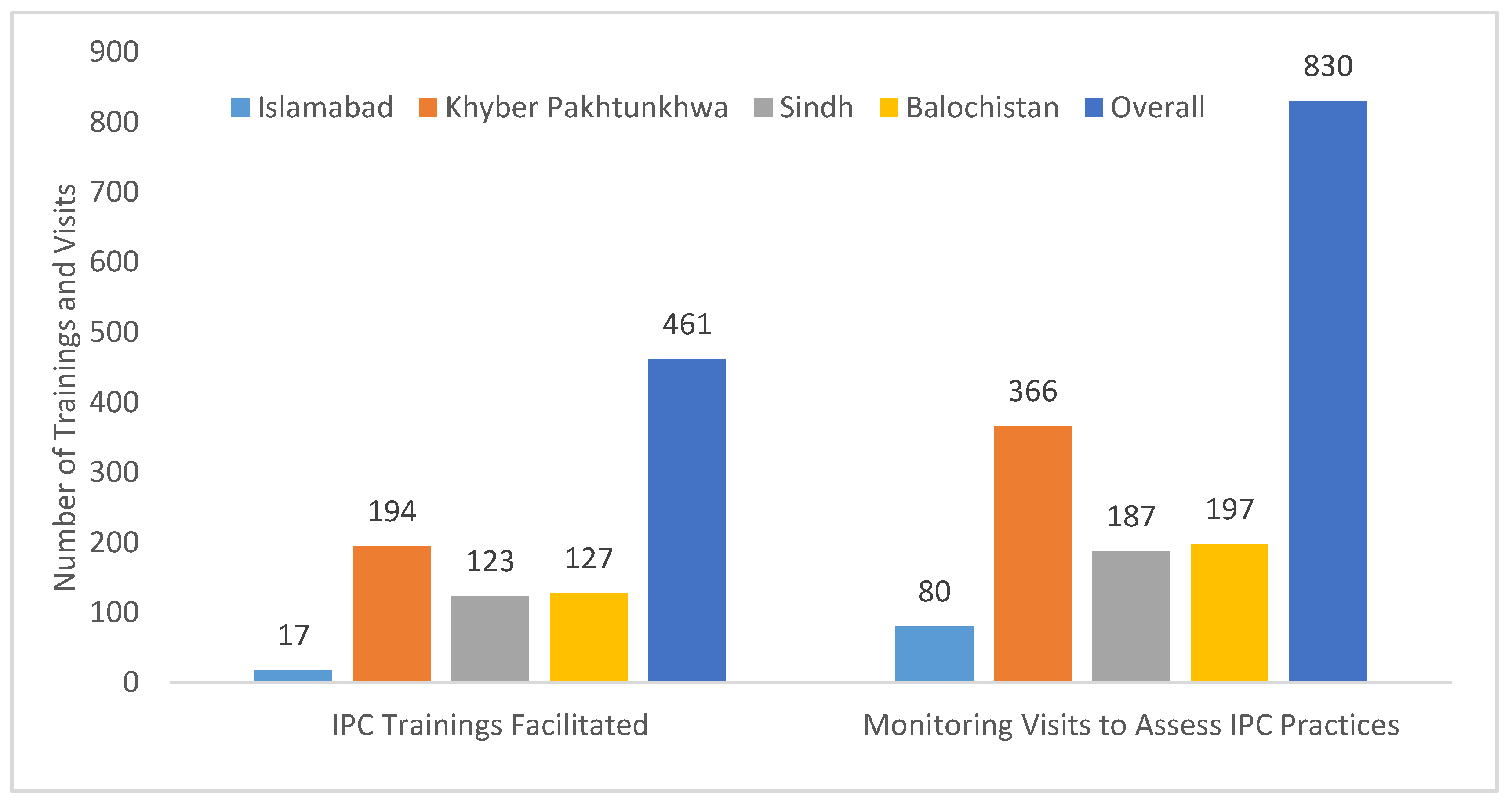

3.7. Infection Prevention and Control

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, H.; Stratton, C.W.; Tang, Y.W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Remarks at the Media Briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020 (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hussain, S.F.; Boyle, P.; Patel, P.; Sullivan, R. Eradicating polio in Pakistan: An analysis of the challenges and solutions to this security and health issue. Glob. Health 2016, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Situation Report–12; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Saqlain, M.; Munir, M.M.; Rehman, S.U.; Gulzar, A.; Naz, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Tahir, A.H.; Mashhood, M. Knowledge, attitude, practice and perceived barriers among healthcare workers regarding COVID-19: A cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Available online: https://polioeradication.org/who-we-are/ (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Wild Poliovirus List: List of Wild Poliovirus by Country and Year. 2019. Available online: https://polioeradication.org/wild-poliovirus-count/ (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Polio Eradication Dept; World Health Organization; Global Immunization Program, UNICEF; Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; Global Immunization Div, Center for Global Health, CDC. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative Stop Transmission of Polio (STOP) Program—1999–2013. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2013, 62, 501. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Islamic Republic of Pakistan. National Emergency Action Plan for Polio Eradication 2013; Government of Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2013.

- Michael, C.A.; Waziri, N.; Gunnala, R.; Biya, O.; Kretsinger, K.; Wiesen, E.; Goodson, J.L.; Esapa, L.; Gidado, S.; Uba, B.; et al. Polio Legacy in Action: Using the Polio Eradication Infrastructure for Measles Elimination in Nigeria—The National Stop Transmission of Polio Program. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216 (Suppl. 1), S373–S379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.G.; Mkanda, P.; Banda, R.; Komkech, W.; Ekundare-Famiyesin, O.O.; Onyibe, R.; Abidoye, S.; Nsubuga, P.; Maleghemi, S.; Hannah-Murele, B.; et al. Ekundare-Famiyesin, Rosemary Onyibe; et al. The Role of the Polio Program Infrastructure in Response to Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak in Nigeria 2014. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213 (Suppl. 3), S140–S146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R.E.; Herrera, D.G.; Kelly, P.M. An evaluation of the global network of field epidemiology and laboratory training programmes: A resource for improving public health capacity and increasing the number of public health professionals worldwide. Hum. Resour. Health 2013, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, R.J. Why is polio still here? A perspective from Pakistan. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e177–e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.E.; McDonnell, S.M.; Werker, D.H.; Cardenas, V.M.; Thacker, S.B. Partnerships in international applied epidemiology training and service, 1975–2001. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 154, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.S.; Dicker, R.C.; Fontaine, R.E.; Boore, A.L.; Omolo, J.O.; Ashgar, R.J.; Baggett, H.C. Building global epidemiology and response capacity with field epidemiology training programs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, S158–S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Greene, S.A.; Burns, C.C.; Tallis, G.; Wassilak, S.G.F.; Bolu, O. Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication-Worldwide, January 2021–March 2023. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tchoualeu, D.D.; Hercules, M.A.; Mbabazi, W.B.; Kirbak, A.L.; Usman, A.; Bizuneh, K.; Sandhu, H.S. Using the Stop Transmission of Polio (STOP) Program to Develop a South Sudan Expanded Program on Immunization Workforce. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216 (Suppl. 1), S362–S367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key Indicators | District NSTOP Officers (n = 56) | TL/DTFs Officers (n = 8) | Overall (n = 64) | Average per Officer Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Coordination: Involvement in response meetings | ||||

| DCCC/Task Team/RR meetings facilitated or attended | 1717 | 387 | 2104 | 33 |

| COVID-19 response-related ERMs or daily meetings facilitated | 3358 | 425 | 3783 | 59 |

| Security meetings attended | 417 | 33 | 450 | 7 |

| B. Case detection and Management | ||||

| COVID-19 suspected cases investigated | 30,461 | 2268 | 32,729 | 511 |

| COVID-19 confirmed cases investigated | 9445 | 2058 | 11,503 | 180 |

| COVID-19 suspected refusals identified and investigated | 468 | 240 | 708 | 11 |

| COVID-19 cases followed up for 14 days | 11,381 | 2332 | 13,713 | 214 |

| COVID-19 case contacts traced/identified | 13,610 | 1673 | 15,283 | 239 |

| COVID-19-positive cases transferred to isolation centers | 2170 | 990 | 3160 | 49 |

| Samples of suspected COVID-19 cases for which collection was facilitated | 52,647 | 4546 | 57,193 | 894 |

| Samples for which transportation was facilitated | 50,549 | 4163 | 54,712 | 855 |

| C. Risk Communication and Community Engagement | ||||

| Mass media programs (TV/radio) attended | 136 | 98 | 234 | 4 |

| Support as technical focal person to the PEOC Coordinator/Commissioner/DC/ADC in interactions with the media | 1126 | 180 | 306 | 5 |

| Community engagement sessions facilitated | 1017 | 79 | 1096 | 17 |

| Participants in community sessions | 17,888 | 546 | 18,434 | 288 |

| Calls at DPCR/Call Center supported as technical expert | 25,178 | 2183 | 27,361 | 428 |

| Facilitated the religious leaders’ engagement through DPCR | 1843 | 54 | 1897 | 30 |

| Facilitated the influencers’ engagement through DPCR | 2114 | 197 | 2311 | 36 |

| D. Training and Orientation Sessions | ||||

| COVID-19 response training sessions for healthcare providers facilitated | 1100 | 104 | 1204 | 19 |

| Participants in response training sessions | 8801 | 1103 | 9904 | 155 |

| Training sessions on PPE use facilitated | 775 | 53 | 828 | 13 |

| Participants in PPE use training sessions | 4257 | 554 | 4811 | 75 |

| Training sessions monitored | 518 | 78 | 596 | 9 |

| E. Surveillance and Screening | ||||

| COVID-19 surveillance committee meetings attended | 681 | 65 | 746 | 12 |

| COVID-19 surveillance training sessions facilitated or monitored | 367 | 50 | 417 | 7 |

| Number of surveillance/screening teams trained | 1369 | 185 | 1554 | 24 |

| F. Establishment and Maintenance of Quarantines/Isolations | ||||

| Quarantine/isolation centers for which establishment was supported | 1681 | 79 | 1760 | 28 |

| Visits to quarantine/isolation facilities | 1251 | 180 | 1431 | 22 |

| G. Infection Prevention and Control | ||||

| Training sessions on IPC facilitated | 461 | 70 | 531 | 8 |

| Facility visits to assess IPC practices conducted | 830 | 205 | 1035 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pervaiz, A.; Safdar, R.M.; Laghari, M.A.; Shah, N.; Mehmood, A.; Ullah, K.; Franka, R.; Mbaeyi, C. Putting the Polio Workforce to Work in a Public Health Crisis: Contributions of the National Stop Transmission of Polio (NSTOP) Program to the COVID-19 Response in Pakistan. Vaccines 2025, 13, 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080875

Pervaiz A, Safdar RM, Laghari MA, Shah N, Mehmood A, Ullah K, Franka R, Mbaeyi C. Putting the Polio Workforce to Work in a Public Health Crisis: Contributions of the National Stop Transmission of Polio (NSTOP) Program to the COVID-19 Response in Pakistan. Vaccines. 2025; 13(8):875. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080875

Chicago/Turabian StylePervaiz, Aslam, Rana Muhammad Safdar, Mumtaz Ali Laghari, Nadeem Shah, Amjad Mehmood, Kifayat Ullah, Richard Franka, and Chukwuma Mbaeyi. 2025. "Putting the Polio Workforce to Work in a Public Health Crisis: Contributions of the National Stop Transmission of Polio (NSTOP) Program to the COVID-19 Response in Pakistan" Vaccines 13, no. 8: 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080875

APA StylePervaiz, A., Safdar, R. M., Laghari, M. A., Shah, N., Mehmood, A., Ullah, K., Franka, R., & Mbaeyi, C. (2025). Putting the Polio Workforce to Work in a Public Health Crisis: Contributions of the National Stop Transmission of Polio (NSTOP) Program to the COVID-19 Response in Pakistan. Vaccines, 13(8), 875. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080875

_Rachiotis.png)