1. Introduction

Vaccination is one of the greatest public health achievements, resulting in the eradication of smallpox globally and the control of diseases including measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, yellow fever, and polio in the United States [

1,

2,

3]. However, vaccine uptake levels must be high to be successful in decreasing infectious disease [

4]. In the U.S., three quarters of adults are missing one or more routinely recommended vaccinations [

5]. Lower uptake has led to a greater number of recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease [

6,

7,

8,

9]. In line with lower vaccine uptake, there are increasing trends of vaccine hesitancy and perceptions that vaccines are not safe [

10].

It is important to understand why people choose to reject vaccines when they are safe, easily accessible, and often free. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and varies across contexts and populations. Contributors to vaccine hesitancy include both individual and group factors, such as personal perceptions and social and peer influences, as well as contextual factors, which can be historic, sociocultural, environmental, institutional, economic, or political [

11]. Hesitancy can also be vaccine-specific, meaning that the risk or benefit of the exact vaccine in question can be influenced by aspects like newness or cost. Additional factors that are key in vaccine decision-making include trust in advice given by healthcare providers, trust in mainstream medicine, and general views toward health [

12]. Ultimately, vaccine hesitancy has been shown to result in vaccine delay or refusal [

13,

14]. Vaccine delay or refusal place both the individual’s health and the health of those around them at risk through community transmission [

15].

Disparities in vaccine uptake are higher in rural areas for routine vaccines [

16,

17,

18]. Adolescents from rural areas receive fewer HPV and meningococcal vaccines [

19], and COVID-19 vaccination is lower in rural areas for all sex and age groups [

20]. Racial and ethnic disparities also exist in vaccine uptake. Black and Hispanic Americans are less likely to receive influenza or pneumococcal vaccines than their non-Hispanic White counterparts in the same age groups [

21,

22]. These data are notable considering that rural and racial/ethnic minority groups also experience an increased disease burden for many diseases with available vaccines. Rural communities experience higher hospitalization rates for immunizable conditions [

23]. Flu hospitalization rates were nearly 80% higher among Black adults from 2009 to 2022 and 20% higher among Hispanic adults than White adults [

24]. Racial and ethnic minorities also experienced disproportionate disease severity regarding COVID-19 in comparison with White adults [

25]. Given the existing demographic and geographic vaccination disparities, it is important to understand vaccine hesitancy among racially and ethnically diverse populations living in rural areas.

Individuals with high levels of vaccine hesitancy often also have high levels of mistrust [

26]. Trusted sources of information may reduce vaccine hesitancy [

27]. However, who community members regard as trusted individuals may vary across populations [

28]. Identifying trusted sources and the ways in which they relay vaccine messages is imperative to reduce disparities in vaccine-hesitant diverse populations.

Determinants of vaccine hesitancy among marginalized communities are not well understood. This study builds on previous work indicating a need for clear, accurate, and trusted information about both COVID-19 vaccines and a wider range of more recently developed vaccines [

29,

30]. The purpose of this study is to understand vaccine hesitancy among racially and ethnically diverse and medically underserved rural populations, to assess vaccine messaging from trusted individuals (e.g., clergy/church leaders, community health workers), and to identify strategies to improve vaccine acceptance among these populations.

3. Results

Overall, 119 individuals participated in the focus group discussions, including 91 community members and 28 trusted leaders. Most community member participants (84%) and leaders (63%) identified as Black or African American. Additionally, 18% of community members and 33% of leaders identified as having a Hispanic ethnicity. The majority of both the community members (70%) and leaders (60%) were female. Only 11% of community members reported attaining a college degree or higher, while 65% of leaders had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Community members had a mean age of 60 (SD 15.2), while the leaders’ mean age was 50 (SD 26.1). Most community members had a family income of less than USD 30,000 (53%). Additional demographic information for the focus group participants can be found in

Table 1.

Responses to the attitudinal survey items indicated that participants had the highest levels of trust for healthcare providers, church/spiritual leaders, and the healthcare system. Participants reported moderate trust in community leaders and the least trust in the media and government (

Table 2). When asked about concerns about receiving vaccines, the most reported concerns were about side effects (47%) and worries about selecting between many available options (46%) (

Table 3). Over a third of the participants had no concerns about receiving vaccines (

n = 37%).

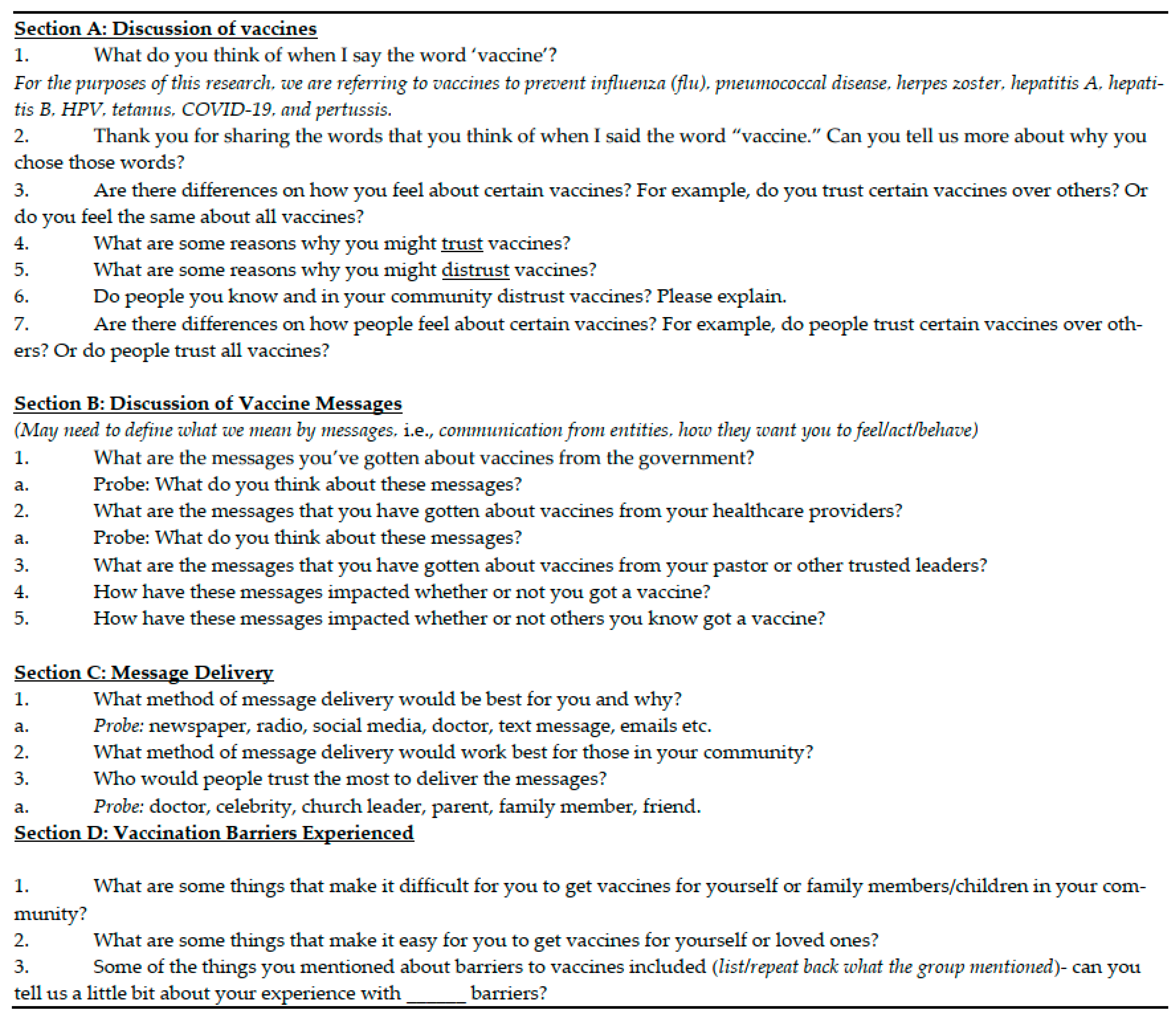

The researchers identified seven key themes from the transcript analysis within the three primary focus areas of the study: understanding vaccine hesitancy, messaging from trusted individuals, and strategies to improve vaccine acceptance. Community member and leader data were analyzed together, as the coding revealed that the qualitative responses were not dissimilar enough to warrant separate analyses. The table in

Appendix B provides illustrative quotes across roles and themes, further demonstrating the similarity in the responses from community leaders and community members and substantiating the need for combined analyses.

3.1. Primary Focus 1: Understanding Vaccine Hesitancy Among Racially and Ethnically Diverse and Medically Underserved Rural Populations

3.1.1. Theme 1: Differences in Trust Based on How Long a Vaccine Has Been Available

When stating reasons to distrust vaccines, participants often felt that newer vaccines were less credible. Participants were concerned that, with new vaccines, there is uncertainty regarding whether they work, confusion about why there are so many so rapidly (e.g., COVID-19 boosters), and why only certain vaccines can be created so quickly.

“I’m trying to figure out why they rushed when there’s other stuff out there killing people like cancer…I mean you get the COVID vaccine approved in less than a year, but you can’t cure nothing else that’s been out here for years.”

(Focus Group 1, Community Member)

When asked about the reasons that they trusted vaccines, many participants said that they trusted the vaccines that they had to receive to attend school as a child and because they had seen over the years that they had worked. However, when asked if they felt differently about various types of vaccines, many participants were skeptical of new vaccines since they were developed and disseminated very quickly and were concerned that they did not work.

“Like [participant name] said about the shots we got when we were kids, I always thought they were good because you know I got those as a kid and … I’m good. So, it was no question when it was time for my kids to get ‘em. When it was time for my kids to get those shots…. No problem. But like she said when they start introducing new stuff. Um, I know we’re not solely talking about COVID today but, just you know when COVID came out, the vaccines came out so quick [snaps]. And so many different ones…. Yeah, I don’t know if I trust that.”

(Focus Group 2, Community Member)

3.1.2. Theme 2: Distrust Influenced by Misinformation, Often Spread Through Social Media

The fears about vaccines that participants shared or mentioned hearing from others were often related to misinformation on social media. Participants specifically mentioned young people as being particularly influenced by social media and believing information that may not be credible.

“I definitely see distrust … because let’s say, someone’s aunt or the friend of someone on Facebook or social media posts like, ’the vaccines are like harming people and causing these other illnesses’. And that could be like completely unrelated to the vaccines, and they’re just attaching it to whatever was going on with them... And they tell their other friends, their husbands, and they start just associating that with negative connotations and with vaccines overall. A lot of like distrust based on misinformation.”

(Focus Group 11, Leader)

“One thing that I’ve noticed… a lot of the young people that are taking social media at face value … a lot of the younger generation right now, they are perpetual rebelers [sic]. They want something to rebel against. And if you present something to them and you’re telling them five reasons why it will help, they will give you six reasons why it won’t.”

(Focus Group 9, Leader)

Some participants reported the view that vaccines are a means of control by the government. Five focus groups, including among trusted leaders, mentioned the idea that the COVID-19 vaccine involved inserting a chip into the recipient that enabled the government to track them. These comments were not always framed to indicate that the participants themselves believed this but that they had heard it from someone else.

“Well, you know, like a chip. Not like a chip but a form of … like radiation, something inside your body… with certain strains it will appear up…like we go to the hospital, and we got to take a CAT scan. They give us something to drink and then they run it through a machine, and they can detect certain things. So, if they use a vaccine to detect, you know, like look at from a certain strain, like okay, there’s a vaccine.”

(Focus Group 1, Community Member)

Participants generally did not prefer the government as a source for vaccine messaging. Some participants felt that messages from the government provided good information, while others had concerns about being controlled, tracked, or lied to. Ideas specific to COVID-19 included skepticism about the politicization of vaccines and false information from government sources.

“Yeah, when the vaccine first started, the first go-round, well, ‘if you take it you’re going to be a zombie.’ I mean this was people in their forties believing this stuff. The government controlling your mind and knowing where you are.”

(Focus Group 10, Leader)

“Going back to the 50/50 because some people trust the CDC. But then with social media, the other half doesn’t trust them … people also see it kind of like in the way that they see like a parent like, ‘oh, they’re just bugging me to manage me. It’s just a form of authority that I don’t want to listen to.’”

(Focus Group 11, Leader)

3.1.3. Theme 3: Concern About Becoming Sick After a Vaccine

Many participants mentioned distrust in vaccines because either they or their family members had become sick after taking a vaccine. The specific vaccines most mentioned in relation to becoming sick after receiving them were the COVID-19 and flu vaccines.

“Um, I do not take those… I took the flu vaccine for five years straight I got the flu. And when I stopped taking them, I haven’t had the flu since then. Had a little slight cold or whatever but I never had the flu for it to be aching all for about three or four days.”

(Focus Group 3, Community Member)

When asked if they felt differently about different vaccines, several participants stated that they did not receive the flu vaccine because it made them sick. Five participants directly stated that the flu vaccine causes the flu.

“When I went to the doctor, he asked me about the flu shot and the COVID. And I told him I had the COVID but I’m not taking the flu because every time my dad would take the flu shot, he would get the flu.”

(Focus Group 6, Community Member)

3.1.4. Theme 4: Trusting Vaccines Due to Seeing the Impact of Not Taking Them

Participants often stated that they personally trusted vaccines because they had been shown to work and kept them alive when they saw others become sick or die. Participants who trusted vaccines also reported that vaccines kept them healthy and saw them as positive.

“… back when we were coming up, I didn’t hear anything about HPV. So, you know when I got older and started hearing about it, I’m like, ‘oh wow what’s that?’ And from a personal experience I know a family member that passed from it. So, that’s why I got my kids vaccinated for it because that’s when I started hearing about when it affected my family… you know it’s for males also. My son is also vaccinated from it. So yeah, because of that personal experience I had, I definitely said, ‘ok yeah, we’re gonna get it.’…new stuff I’m kinda skeptical, about … you know just gotta weigh your pros and your cons. Gotta weigh your options.”

(Focus Group 2, Community Member)

Some participants described a comparison of their own experiences pre- and post-vaccination—for example, noticing how much sicker they were when they had COVID-19 before being vaccinated versus a milder form afterwards.

“I got COVID and then I got vaccinated, right? I caught it again after I got vaccinated. The reason I went and got the booster, although it wasn’t mandatory for my job, is because I saw the difference in when I didn’t have it, when I wasn’t vaccinated. I thought I was about to die.”

(Focus Group 1, Community Member)

3.2. Primary Focus 2: Assessing Vaccine Messaging from Trusted Individuals

3.2.1. Theme 5: Trusted Leaders Advise People to Conduct Their Own Research on Vaccines

When asked what they would advise community members to do regarding vaccination, trusted leaders advised people to conduct their own research rather than listen to anyone else. Every group specifically used the term “do your own research”.

“I would definitely advise anyone to do their own research…. I could tell you anything, your doctor could tell you anything, your pastor could tell you anything. But, if you don’t look it up for yourself… you will never know. So, I always advise people, ‘do your own research.’”

(Focus Group 9, Leader)

When trusted leaders gave advice for people to conduct their own research, they often mentioned using valid websites or trusted sources. Examples of trusted sources included the health department or someone from the community who had already taken the vaccine.

“First, I would tell them to learn all they can about the disease; what it does, what would happen to you if you had the disease, and to be specific. Look at it from your age group. So, someone getting chickenpox at five years old it’s going to be vastly different than someone getting chickenpox [at] my age. Or, like mumps. I’ve never had them so when I was working in the hospital one time, I had to go home. There was a gentleman on the floor with mumps. The director of nursing, she was like, ‘we have mumps’ and she said, ‘I’m sure everybody here had it’ I said, ‘I’ve never had mumps.’ She said, ‘you may leave.’ Mumps in a child is fine. If you are of childbearing age, mumps can make him sterile. Yes, that’s why it’s dangerous in men. So, find out how that affects your group. Go to valid websites.”

(Focus Group 10, Leader)

3.2.2. Theme 6: Trust in Messages from Medical Providers

Participants viewed their doctors telling them to take a vaccine as one of the main reasons that they trusted vaccines.

“I believe that we all have a trusted doctor. And we go with the opinion of that doctor. Why? Because we trust him and maybe he’s been seeing us, the family, everyone for many years, and maybe we’ve seen the sequence that has been correct, so we say, ‘well, yes.’”

(Focus Group 8, Community Member)

Participants also reported a clear preference for vaccine messaging to be delivered by a medical professional. Although responses for the method of delivery varied widely (church, radio, email, senior center, etc.), there was largely a consensus on doctors as the preference regarding who should deliver the message.

“The doctor would be more up to date than the media would. If there was word out there, I think the healthcare provider would know because they’re familiar with things. They’re getting more information about it all the time. To me it was just get a shot, boom, boom.”

(Focus Group 6, Community Member)

Although most participants reported trusting vaccine messaging from healthcare providers, several participants actively stated that they did not trust doctors and that doctors pushed people to be vaccinated.

“Because I had one doctor that was trying to get me to get it because of my health situation and I had to tell him to stick to his topic of treating me, for what he treated me for. I mean don’t push me to get COVID shots. It ain’t going to cure me.”

(Focus Group 1, Community Member)

3.2.3. Theme 7: Social Determinant Barriers to Vaccination (Cost, Education, Transportation)

The major reported structural barriers to vaccination were a lack of transportation, the high cost, and a lack of education to make informed decisions about whether to be vaccinated. Nearly every focus group mentioned transportation as an issue. Unawareness of aspects like the actual cost of vaccines or the availability of payment based on a sliding scale was another barrier mentioned by both community members and leaders. Participants mentioned that vaccines could be very expensive without insurance. Participants also reported instances of vaccines not being available or difficulties in navigating the process of finding and paying for them.

“Transportation also is definitely a barrier, because I work [in] transportation, and if the referrals of people they can’t get to their appointments because they don’t have a way, or they don’t have the gas… You know our location itself… they’re putting up doctor’s offices in smaller areas so it’s a little easier to get there but you know, transportation is a barrier for a lot of people. The elderly um, it’s just bad for them.”

(Focus Group 2, Community Member)

“… a vaccination campaign, for example. If a campaign like that were to happen here, I assure you that there would be a crowd because many people want it and can’t afford that vaccine. So, organizing campaigns…with specific vaccines… what people need most and don’t have access to, either due to the price or because they don’t have access to health insurance, right? So, health authorities should organize these vaccination campaigns … for people in rural areas. But what happens?… The quota is very limited. If people go, they’re told ‘no, you’re not a farm worker’ or ‘you don’t live here.’ They ask for proof of residence and ‘no, it doesn’t match,’ so you’re turned away.”

(Focus Group 8, Community Member)

When asked about facilitators of vaccination, participants often mentioned factors that would make it easier to receive vaccines but were not currently in place. Participants stated that they would like to see mobile units or home visits for vaccination but that many ended after the COVID-19 pandemic or did not provide vaccinations. Having free or low-cost options and public campaigns to increase awareness and education were suggestions raised to facilitate vaccination.

“I wonder if it would be good like for people who are house bound, have someone to come in. I know like with insurance companies with my sister they had someone come in and do these tests and everything. If they had someone like that who could come in and give vaccinations, someone that you trust, not just anybody coming in.”

(Focus Group 1, Community Member)

4. Discussion

Overall, our findings indicate varied factors influencing vaccine hesitancy among this racially and ethnically diverse and medically underserved rural population. Many felt that seeing people become sick from vaccine-preventable diseases and being advised by their doctors led to greater trust in vaccine efficacy; however, skepticism over new vaccines, concerns about becoming sick after vaccination, and misinformation on social media continue to impact vaccine hesitancy. Quantitative attitudinal data supported the qualitative findings, indicating high trust in healthcare providers and worries about becoming sick from vaccines. The community members’ and leaders’ qualitative responses were more similar than expected, leading to the study team’s decision to combine these responses for the qualitative analysis. The leader sample had markedly higher levels of formal education, which has been linked to reduced vaccine hesitancy, yet we found hesitancy and reports of misinformation in both groups [

34].

Our results showed differences in trust based on how long a vaccine has been available. A scoping review of studies published during the COVID-19 pandemic found that many people’s reason for refusing vaccination included thinking that a vaccine produced in a rush is too dangerous [

35]. One study, specifically including Hispanic populations in rural South Carolina who had not been vaccinated for COVID-19, found that participants feared that the vaccine’s development had been rushed and that being vaccinated might cause them to become sick and miss work [

36]. An additional qualitative study conducted in ENC found that participants distrusted the COVID-19 vaccine because they felt that it was developed too soon and were concerned about side effects [

30]. These findings align with our study results indicating that there is less trust in newer vaccines and concerns about becoming sick after vaccination. The skepticism about how vaccines are able to be produced so quickly indicates a need for public health education that focuses on how vaccines are created.

Our study’s findings on vaccine misinformation from the media align with previous work indicating that the internet and social media are major drivers of inaccurate data or misinformation about vaccines [

37]. Additionally, research indicates that social media users are more likely to believe information from non-scientific or pseudoscientific influencers than scientific information [

38]. This may reflect larger contextual factors, like the wider decline in trust in expertise and authority [

39]. The participants often referred to younger people as the main group who believe information that they read on social media. A study examining rural and urban young adult vaccine hesitancy for the COVID-19 vaccine found that rural participants had 40% lower odds of intending to receive the COVID-19 vaccine [

40].

When participants discussed becoming sick after a vaccine, it was not always clear whether they were describing side effects from the vaccine or later becoming sick with the disease that the vaccine was intended to prevent. For example, multiple people stated that they or their family members contracted the flu from the flu vaccine, but this is not medically possible [

41]. This indicates a need for further education differentiating between reactions after a vaccine and contracting the disease. One study indicated that people who did not receive the flu shot and later contracted the flu had a higher likelihood of being vaccinated the next year. However, those who received the flu shot and still later contracted the flu were less likely to be vaccinated the next year [

42]. Providing nuanced information indicating that some vaccines do not prevent all strains, like the flu, or may result in a less severe case of the disease rather than no disease (e.g., COVID-19), could reduce fears that vaccines do not work.

Alternatively, participants voiced feelings of trust in vaccines after seeing the impacts that diseases have on those who are unvaccinated versus those who have been vaccinated. At times, this included participants’ families experiencing disease or even experiencing disease themselves and then deciding to be vaccinated. Seeing people that one knows experience the negative effects of diseases may increase the perceived risk and severity. This was demonstrated in a previous study using the Health Belief Model to predict vaccine intentions related to COVID-19 [

43].

When assessing vaccine messaging from trusted leaders, the advice from the leader focus groups was largely for community members to conduct their own research on vaccines. A recent study examining how the slogan “do your own research” has been used online (public posts on Instagram and Facebook) found that this slogan is often used by anti-vaccine activists but also can be used to activate civic responsibility [

44]. These types of messages promote individual responsibility for navigating online information and may reflect wider societal distrust of institutions. Notably, trusted leaders provide this suggestion, rather than to speak with a physician, while participants themselves preferred to receive messaging from healthcare providers.

Public health efforts can work to counteract anti-science narratives through repairing trust in vaccines and in the government and other groups. These efforts can work through community-level strategies like educational campaigns and community health worker-delivered interventions and through provider-level strategies such as provider vaccine recommendation interventions. Community-level strategies should promote accurate vaccine information and should highlight the importance of talking to a trusted person like a healthcare provider for guidance and information about age-appropriate vaccines. Educational campaigns and community health worker interventions should promulgate the idea to “do your own research” but also equip the community with the skills to identify the differences between reputable and biased vaccine informational sources. Provider vaccine recommendation interventions should work with healthcare providers to ensure that they provide strong, clear vaccine recommendations to their patients to increase the uptake of vaccines. Providers should explain the benefits of vaccines while addressing any patient concerns. It is interesting that, while this study utilized a trusted messenger approach, community members largely wished to hear vaccine messaging from medical providers. Previous research among both rural populations and racial and ethnic minorities has supported the notion of strengthening vaccine campaigns by including messaging from trusted individuals [

45,

46]. This is consistent with the present research team’s previous work showing that the preferred COVID-19 vaccine messaging was through word of mouth and personal testimony from trusted individuals [

30]. However, a narrative review of HPV vaccine trust among racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. showed high levels of trust in doctors and healthcare providers but less trust in pharmaceutical companies and government agencies [

47]. As healthcare providers are a trusted source for vaccine information, it is important that providers have training to consistently provide clear and accurate recommendations. Previous work found that providers outside of the U.S. Southeast had 5.2 higher odds of recommending COVID-19 vaccination, indicating a need to improve provider vaccine recommendations in the Southeast [

29].

Lastly, the identification of strategies to improve vaccine acceptance should consider social determinant barriers to vaccination. Our findings included barriers such as cost, education, and transportation, which are consistent with the literature. A qualitative study on barriers to HPV vaccination in rural Georgia also found transportation to be a barrier to vaccination [

48]. In rural, medically underserved locations, the distance to a medical center can be large. The distance to providers was also found as a barrier in a systematic review of early childhood immunization in the rural U.S. [

49]. Another study examining vaccination among older adults found associations between cost and vaccination, as well as additional barriers for less educated, minority, and rural participants [

50]. The majority of participants in this study reported a low family income, which aligns with the qualitative finding that cost is a barrier. Access issues are often focused on not bringing services to the community and people needing to find out how to access the service, in terms of both transportation and payment, as well as other restrictions, like residential requirements. Even if negative perceptions about vaccinations improve, if structural barriers persist, they will impede optimal vaccine uptake.

This study is not without limitations. Participants willing to participate in a focus group about vaccines may have different views compared to those who prefer not to share their opinions. The sample for this study was self-selected and consisted of mostly Black/African American, female, older adults with a lower income, which limits the generalizability of the results and could have introduced selection bias. The demographic survey did not ask about the jobs or roles of trusted leaders (i.e., pastor, community health worker, government worker, etc.), so we were unable to include this information in our interpretation of the data. Data on the professions of the community leaders were based on the memory of the focus group moderators. The demographic survey was completed in person prior to the focus group discussion to ensure a better response rate, but not all participants fully completed the demographic survey. In addition, although we captured participants’ levels of trust in organizations (e.g., healthcare system, government, media) (

Table 2), understanding the difference between “somewhat” trusting and “not at all” trusting, and its association with vaccine decisions, would have been important. Thus, future research concerning vaccine hesitancy should disentangle the difference in the levels of trust and their impacts on vaccination uptake. Our findings indicate that medical providers are key to trust in vaccines and a desired messenger for vaccine information. However, distrust linked to fear and misinformation and structural barriers to vaccine access persist.