Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated immediate regulatory vaccine approvals to facilitate timely global access. The prevailing differences in economies and resources and the varying maturity of the regulatory systems worldwide resulted in different levels of capacity to ensure vaccine quality, safety, and efficacy. In addition to the Emergency Use Authorization or equivalent by some advanced regulatory agencies, the WHO issued Emergency Use Listings (EULs), among other tools, to streamline and expedite regulatory approvals globally. This study aimed to assess the regulatory strategies and best practices adopted during the COVID-19 vaccine approvals and gather lessons for future emergency preparedness. Methods: A mixed-method approach employing qualitative desk reviews and a cross-sectional study collected data from 194 national regulatory authorities (NRAs) across all WHO regions. Results: Three main approval processes were identified: procurement-driven, reliance-based, and independent evaluations. Wealthier countries with more mature regulatory systems were found to spend a longer time issuing approvals, primarily due to being the initial assessors of the vaccines’ quality, safety, and efficacy. Furthermore, various regulatory flexibilities and best practices centered around regulatory reliance, rolling reviews, fast-tracking reviews, and employing digital tools were identified. Notably, the WHO’s EULs were essential in facilitating the timely approval of vaccines globally, including in low- and middle-income countries. Conclusions: The findings suggest a significant turn in vaccine regulation theories and practice, emphasizing balancing speed with scientific validity. This necessitates the creation of thorough provisions for emergency preparedness, regulatory reliance, and administrative flexibility in regulatory practices worldwide.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic posed a global public health emergency nearly a decade after the H1N1 influenza pandemic 2009–2010 [1]. With over 770 million recorded COVID-19 cases and approximately 7 million deaths by 2024, every country required access to life-saving vaccines as quickly as possible. In addition to other medical products, such as personal protective equipment (PPE) diagnostics, and vaccines were essential for controlling the pandemic [1,2].

Robust regulatory systems protect the public from inadequate-quality, unsafe, or inefficacious medical products. Inefficiencies in such systems, including unnecessary delays in regulatory approvals, can directly affect access to these life-saving medical products, including vaccines [3]. The approval of the COVID-19 vaccines served as a significant test of global regulatory readiness for public health emergencies, offering valuable lessons for enhancing future responses to similar situations.

After the experience of the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the World Health Organization(WHO) developed guidance and recommendations for national regulatory authorities (NRAs) to enable them to expedite the process of marketing authorization without compromising the quality, safety, and efficacy of the vaccine products. In the H1N1 influenza pandemic 2009, the WHO developed regulatory preparedness guidelines for the market authorization (MA) of influenza vaccines in non-vaccine-producing countries. The guidelines highlighted the steps to ensure regulatory flexibility and emphasized reliance on multi-sectoral participation [4]. By adhering to the principles contained in these guidelines, the regulatory authorities (RAs) in non-vaccine-producing countries could undertake the regulatory oversight of influenza vaccines during public health emergencies [5,6]. In September 2020, the WHO developed guidelines on “Consideration for evaluation of COVID-19 vaccines”. Revised in 2022, this document not only provides advice to manufacturers on both the process and the criteria that the WHO will use to evaluate COVID-19 vaccines that are submitted either for prequalification (PQ) or for Emergency Use Listing (EUL), but also can be used by the NRAs in proceeding to marketing authorization of these vaccines [7].

Other measures by the WHO included the development of the Quality Management System (QMS) guideline to guide Member States in improving and implementing their QMS for optimizing regulatory processes, including defining potential risks in providing regulatory oversight [8,9]. Also, in 2016, WHO initiated the Global Benchmarking Tool (GBT) to enable the determination of RAs’ capacity and the subsequent Institutional Development Plan (IDP) to improve regulatory practices, including the level of preparedness [10,11].

Typically, very short timelines are allocated for reviewers to process MA applications for medical products required to address public health emergencies. Thus, independent reviews by individual Member States potentially delay public access to these life-saving products. By promoting reliance practices, WHO aims to minimize duplication of effort and increase access to regulatory expertise among the MS. As a result, WHO released special guidelines on Good Reliance Practices in regulating medical products [12]. WHO also advocates for reliance through the Collaborative Registration Procedure (CRP), reliance on Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRA) and WHO-Listed Authorities (WLAs), and WHO’s Emergency Use Assessment and Listing (EUL) [13,14,15]. Through these mechanisms, the WHO envisioned the assurance of timely registration of much-needed vaccine products by reducing the time needed for their regulatory approvals [16].

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, WHO and collaborating partners through the COVAX initiative played a key role in facilitating the regulatory approval of vaccines in its MSs. These efforts ensured timely access without compromising quality, safety, and efficacy. They included the timely provision of training to create adequate awareness among NRAs on pre- and post-authorization data and other key aspects. Also, the WHO coordinated the review process, shared information under confidentiality agreements, and guided national deployment and vaccination plans. These collaborative efforts allowed the timely issuance of in-country authorization for use and the shipping of over 1.3 billion doses of vaccines by March 2022, providing faster access to quality-assured vaccines through informed reliance practices [17,18].

This study aimed to assess the best practices and adaptive strategies employed during the regulatory approval processes for COVID-19 vaccines within the WHO and its MSs while identifying potential areas for improvement. The presented findings will assist the development of expedited registration pathways for future vaccines, improving regulatory preparedness for public health emergencies.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

A mixed-method study design employing thematic/content analysis (qualitative) and an analytical cross-sectional study (quantitative) was used to explore the pathways for approving COVID-19 vaccines, their flexibility, timing, and approval status, and various best practices.

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

In total, 194 NRAs from WHO MSs across all WHO regions participated in the study. The study was conducted between February 2021 and March 2022, during which purposefully selected key informants/contact persons from respective NRAs provided the WHO regional offices with the needed data, documents, and online resources. Total population sampling was employed to include NRAs from all MSs. Given the pandemic status, this approach aimed to ensure the maximum possible representation of practices and experiences from all the WHO regions, including economic status and the NRA’s maturity levels.

2.3. Data Collection Methods

The COVAX Tracker was primarily used to capture quantitative data related to vaccine regulatory approvals, timelines, and distributions. It was newly developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to provide real-time tracking of such aspects and regulatory statuses through the COVAX facility. The COVAX Tracker collected data across several variables, mainly grouped into geographic information, manufacturer details, and regulatory outcomes. This yielded structured numeric, categorical, and text-based data from close-ended responses.

Structured self-administered questionnaires and checklists were utilized to collect the necessary data from the key informants and documents. While the questionnaires were distributed to the participants for them to provide the requested information, the checklists were filled with information gathered during the desk reviews of papers and online resources. The document review was conducted by a multidisciplinary team of seven professionals from the World Health Organization (WHO), the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA), the Pharmaceutical Management Science Association (PMSA), the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, and the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA). The validity and reliability of the data collection tools were evaluated through a pilot study involving the first 20 national regulatory authorities (NRAs). Further modifications were made to enhance clarity, improve flexibility, and incorporate any overlooked information following the pilot study. All key informants and respective NRAs provided informed consent and participated voluntarily.

2.4. Variables and Measures

The qualitative part of the study explored the major approaches to the regulatory approval of COVID-19 vaccines and the types of regulatory flexibilities employed during the approval process. Inductive thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data from the desk reviews of documents. Two independent coders analyzed the qualitative data to identify recurring themes and patterns, resolving discrepancies through discussion until a consensus was reached. Themes were derived directly from the data without preconceived notions or theories.

The independent variables in the quantitative study included the World Bank economic status and the WHO-GBT maturity level (ML), whereas the dependent variable was the time of approval (TA). The independent variables were obtained from official World Bank and WHO documents, while the TA was measured as the number of days taken for the approval of various COVID-19 vaccines. Moreover, descriptive statistics were used to establish correlations between the dependent and independent variables by determining the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [14,18,19].

3. Results

A total of 194 NRAs were studied, of which the details related to their regional distribution, World Bank economic status, and WHO-GBT maturity level are as described in Table 1 below:

Table 1.

Details of the studied NRAs.

3.1. Approaches to Regulatory Approvals

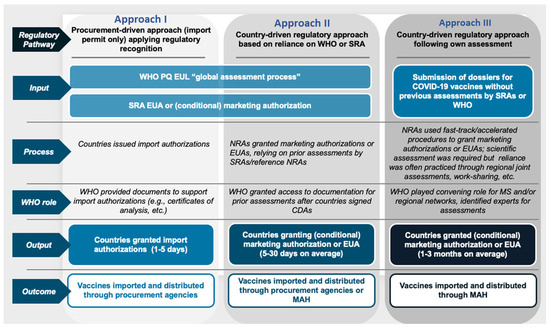

The approaches to regulatory approvals undertaken by the studied Member States were found to fall into three major categories (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Three approaches followed by the Member States to the regulatory approval of COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic.

These included a procurement-driven/import-permits-only approach, whereby the authorization was granted based on the regulatory recognition of the WHO PQ, EUL, or SRA EUA/conditional MA. Depending on the local settings, the authorizations could be given by the respective NRA, Ministry of Health, or cabinet. Such countries were typically observed to issue the authorizations within 1 to 5 days, which was followed by the importation and distribution of the vaccines through the available procurement channels.

Moreover, other states followed the country-driven regulatory approach, which relied on prior assessments and data from the WHO and SRAs to grant conditional MA or EUA. This approach was reported to take 5 to 30 days to issue authorizations, and the vaccines were thereafter imported and distributed by procurement agencies or MAH.

Further, the final category included granting conditional MA or EUAs following their own assessments by the respective countries. This required the submission of the respective dossiers for COVID-19 vaccines without previous assessments by the WHO or SRAs. Special fast-track or accelerated procedures were put in place by the NRAs to perform scientific evaluations and leverage regional assessments and work-sharing initiatives. The respective MAH thereafter undertook the importation and distribution of the vaccines. Taking the WHO-European region as an example, the distribution of the Member States into the categories described above is indicated in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Distribution of Member States in different WHO regions based on approaches to the regulatory approval of COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic.

3.2. Types of Regulatory Flexibilities Applied to COVID-19 Regulatory Approvals

Countries were observed to employ a range of regulatory flexibilities to enable the timely approval of COVID-19 vaccines. Most of the implemented measures covered various aspects of registration and marketing authorization, including submission, evaluation, and final authorization (Table 3). The measures were notably geared toward ensuring the timely availability of vaccines through improved regulatory efficiency and flexibility.

Table 3.

Types and key outcomes of regulatory flexibilities employed by Member States over various regulated products during the COVID-19 pandemic.

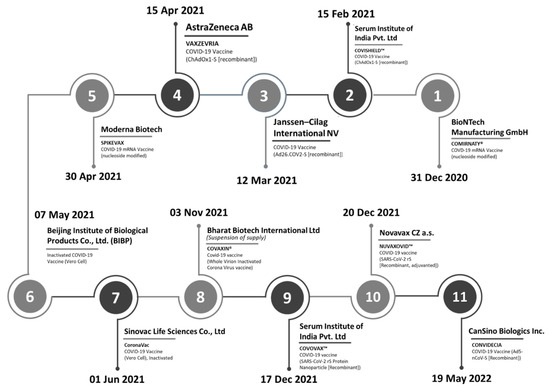

3.3. Status and Timing of Member State Approvals

Over the 16-month duration between December 2020 and March 2022, the WHO issued an Emergency Use Listing (EUL) for eleven COVID-19 vaccines of different natures from manufacturers (Figure 2). These included two mRNA vaccines, six recombinant vaccines, and three inactivated whole virus vaccines, which companies with plants in multiple locations around the globe had manufactured. In cases where an SRA has assessed the vaccines submitted for a EUL, the WHO relied on the assessments already available to conduct a risk-based evaluation of the respective products.

Figure 2.

Timeline of the WHO’s Emergency Use Listings of COVID-19 vaccines.

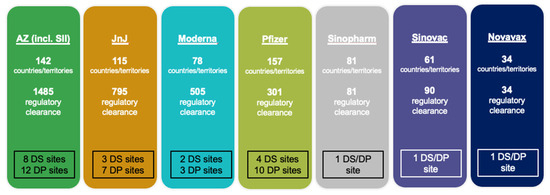

As of 22 February 2022, seven vaccines with EUL by the WHO had been approved and given regulatory clearance across multiple countries and territories. Leading the trend was VAXZEVRIA®/COVISHIELD® (AstraZeneca/Serum Institute of India), which had been approved in 142 countries/territories with a total of 1485 regulatory clearances allowing the initial authorization for use and authorization for any subsequent changes (Figure 3). The vaccine also involved the most drug substance (DS) sites (eight) and drug product sites (twelve). Other vaccines with higher approval and regulatory clearance frequencies included those manufactured by Janssen-Cilag International NV and Pfizer/BioNTech Manufacturing GmbH.

Figure 3.

Status of member state approvals for seven COVID-19 vaccines issued EULs by the WHO (AZ = AstraZeneca, SII = Serum Institute of India, JnJ = Johnson & Johnson, DS = drug substance, DP = drug product).

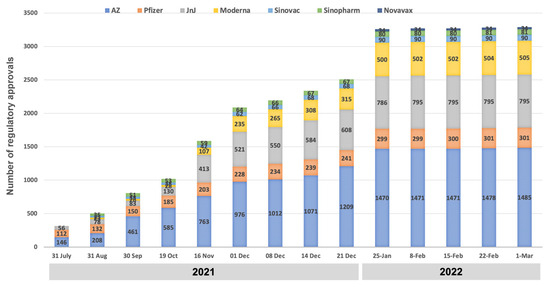

As of 1 March 2022, the seven vaccines with the WHO EUL status had obtained 3291 regulatory approvals across 183 countries/territories, with the respective authorities’ target for issuing EUAs set at 14 days (Figure 4). The VAXZEVRIA®/COVISHIELD® vaccine (AstraZeneca/SII) was the first available for distribution via the COVAX initiative. Within 15 days of its WHO EUL, it was granted import permits/approvals in 101 out of the 145 countries/territories seeking to receive vaccines via the COVAX initiative.

Figure 4.

Status of regulatory approvals for seven COVID-19 vaccines in 183 Member StatesMember States, as of 1 March 2022.

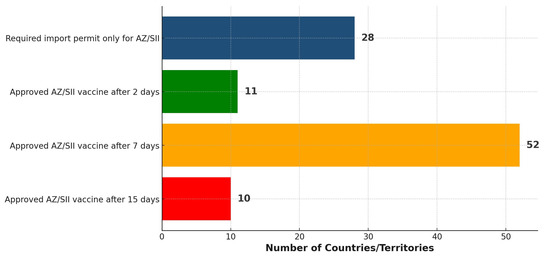

Among the 101 countries/territories, it was found that 28 required just an import permit for the AZ/SII vaccine before its distribution (Figure 5). Moreover, the majority (63) of the countries/territories had issued approval for the vaccine within two to seven days after listing by the WHO. By the end of the 15 days, 21 of the 145 countries had not approved the vaccine but relied on at least one expedited pathway. Further, 23 other countries had not approved the vaccine, in addition to not relying on any expedited pathway.

Figure 5.

Distribution of 101 countries/territories based on the timing of approving/importing the AZ/SII vaccine within 15 days following the WHO EUL.

3.4. Wealth Status and Regulatory Maturity Level as Predictors of Timely Acceptance of Vaccines

A weak positive correlation (ρ = 0.36) (two-tailed p = 0.00) was observed between the four ranks of World Bank (WB) status and the time of approval of the AZ/SII vaccine. On the other hand, a moderate positive correlation (ρ = 0.51) (two-tailed p = 0.00) was observed between the WHO maturity level ranks and the vaccine’s approval time (Table 4). Therefore, the results indicate a significantly longer approval time with increased wealth and regulatory maturity.

Table 4.

The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the ranks reflects the country’s wealth and regulatory maturity.

3.5. Other Reported Best Practices Around Approvals of COVID-19 Vaccines

Best practices under four major categories were reported to have been adopted in response to undertaking various regulatory functions (Table 5). These included pre-planning for emergencies by having an emergency preparedness plan that prescribes clear regulatory pathways, enabling speedy responses/regulatory actions. Other best practices were reported in practicing regulatory reliance on reference authorities and institutions, increased flexibility in discharging regulatory functions, optimal coordination of key stakeholders, and approaches to sustaining regulatory efficiency post-pandemic. Given the unpredictable nature of emergencies, the adopted best practices were essential in stepping out of standard routine operations and expediting regulatory approvals and other actions.

Table 5.

Description of best practices and respective activities in approving COVID-19 vaccines.

3.6. Lessons Learned

Several lessons were highlighted at the global level. These include developing a standing system for coordinating global regulatory approvals and product distribution systems during public health emergencies. This will avoid delays and inefficiencies during emergencies. Moreover, a shared understanding of best practices between donors and regulators is needed to prevent donations of nearly unfit products and the donor-driven selection of recipient countries for the donated vaccines.

Also learned was the essence of balancing the urgent need for vaccines and the need to respect and uphold the national regulatory process, representation in assessment processes, and adherence to confidentiality agreements. Regarding financial and human resource flexibility, rapid hiring can manage an increased workload and minimize operational inefficiencies and staff burnout. Furthermore, global partners must build strong and functional relationships with decision-makers at the country level before emergencies to avoid the difficulty of doing so during emergencies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Approaches to Issuing Regulatory Approval for COVID-19 Vaccines by NRAs

Three main pathways to the regulatory approval of COVID-19 vaccines were adopted based on the respective country’s level of involvement/interest in undertaking independent assessments. These included a procurement-driven approach, a country-reliance approach, and a country/region-driven independent assessment approach. Other studies have reported similar pathways for COVID-19 vaccine approvals by different countries. Employing reliance mechanisms, rolling reviews, collaboration among the NRAs and the WHO, EULs, and EUAs were reported to have accelerated the approval processes and the subsequent availability of vaccines [20,21]. For example, 45% of the COVID-19 vaccines in Latin America were reported to have been approved through the reliance pathway compared to 21% of the vaccines being approved through independent assessments [20]. Strong international cooperation (among countries, regions, and other global organizations) and streamlined regulatory communication and decision-making through digital tools primarily facilitated these actions [21,22].

On the other hand, political factors, vaccine nationalism, geopolitical preferences, the lack of transparency, institutional inefficiency, bilateral procurement outside the COVAX initiative, and working in silos have been linked to slower regulatory approval processes [20,21,22]. Although many NRAs did not receive direct applications for vaccine registration or approval, the WHO served as a hub for providing access to relevant quality, safety, and efficacy data, along with appropriate assessment and evaluation reports. This crucial role enabled informed reliance and highlighted that manufacturers cannot be expected to submit applications to multiple countries at once during emergencies, emphasizing the need for the WHO to take on a coordinating role. These findings have, therefore, highlighted the critical role of international regulatory collaboration and various adaptability mechanisms to deliver efficient and highly reliable regulatory processes during emergencies. However, it is essential to acknowledge the importance of rigorous scientific evaluation in providing regulatory approval, a process that has faced criticism in certain contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic and deserves careful consideration in future vaccine approval assessments. It is important to note that, in some instances, the need for rapid authorization has restricted the ability to evaluate the long-term effects of new vaccine platforms, highlighting a crucial area for consideration in future emergency use guidelines and post-market surveillance plans.

4.2. Adopted Regulatory Flexibilities for Approval of COVID-19 Vaccines

Countries/territories employed a range of regulatory flexibilities to expedite the approval of the COVID-19 vaccines while maintaining optimal oversight of other (non-COVID-related) medical products. The current study has highlighted the flexibilities undertaken across the key domains of registration, evaluation, authorization, market surveillance, licensing, inspections, clinical trials, and lot release. These efforts were primarily stated to reduce the administrative burden, improve efficiency, avoid delays, and optimize resources, allowing timely access to quality-assured vaccines and other non-COVID-related medical products. Other studies have reported that regulatory flexibilities are critical in accelerating vaccine development and clinical trials, such as combined clinical trial phases, pre-submission discussions, and rolling submission on manufacturing validation [23,24].

Furthermore, operational and digital adaptations, such as issuing waivers for product sample submissions and remote working in selected functions, should be regarded as crucial in safeguarding the continuity of the supply chain while maintaining regulatory oversight [21,24,25,26]. Tshering et al. highlighted the essence of expedited EUA processes and interim guidelines in significantly reducing regulatory approval and licensing timelines [25]. Discussions are ongoing concerning the need for regulatory agencies to use the experiences gained during the pandemic to implement appropriate long-term regulatory efficiencies [24]. Long-term flexible regulations will also allow the agencies to adapt to the changing landscape of vaccines manufacturing and ensure timely access to essential health products during emergencies and beyond.

4.3. Effect of WHO EUL on the Status and Timing of COVID-19 Regulatory Approvals

As demonstrated by the rapid and substantial number of regulatory approvals and clearances, the WHO’s EULs substantially enabled a fast and coordinated response to the pandemic through an accelerated global approval process of COVID-19 vaccines. Although conducting independent assessments resulted in the longest time for approval, in some cases, fast-tracked procurements using regional assessments and other work-sharing initiatives were possible. Other scholars have also highlighted the essential role of the WHO’s EULs and other collaborative regulatory efforts in expediting global vaccine approvals [20,27,28].

Despite the observed success, a critical need remains for the continued and detailed evaluation of the approved vaccines’ safety and effectiveness to provide a more in-depth assessment/verification of the processes used to grant the EULs or EUAs [29]. Furthermore, considering the differences in long-term performance and safety profiles among the vaccine platforms, ongoing post-market surveillance methods are essential for generating real-world data. Efforts should also be made to implement more structured EUA and pre-approval access routes to address the observed inequities in vaccine access due to the existing socioeconomic and geographical barriers [30]. These findings, therefore, advocate for continued measures to modernize regulatory processes and promote international regulatory collaboration during emergencies to facilitate a rapid response and access to essential medicines.

4.4. Variation of COVID-19 Vaccines Approval Timelines with Wealth Status and Regulatory Maturity Levels

Higher wealth or regulatory maturity levels were associated with longer approval timelines due to complex and lengthy approval processes. These regulatory authorities are usually the first regulators to evaluate the submission, ensuring a complete evaluation of the quality, non-clinical, and clinical aspects. Hence, lengthy and stringent evaluations are needed compared to approval via reliance mechanisms. Thanks to reliance, most LMICs achieved faster approval rates because they only processed vaccine import permits [20,31]. Further, insufficient competent human resources and well-structured processes contributed to a higher reliance on external agencies and networks for the approval of vaccines among regulatory agencies in the LMICs [20,21,27,32].

However, despite the faster approvals, most LMICs were reported to have achieved lower vaccination rates due to their limited access to vaccines, geographical barriers, logistical constraints, and a lack of adequate vaccination machinery [21,30,31,33,34]. While thorough review processes are highly relevant in ensuring comprehensive quality and safety evaluations, finding a good balance between approval time, adequacy of the review, and accessibility to vaccines should be regarded as crucial in providing timely and optimal vaccination rates [21,29]. Among these measures will be to learn from the trust given to the WHO’s EULs by countries with lower wealth and regulatory maturity statuses, leading to enhanced speed in vaccine approvals during public health emergencies.

4.5. Adopted Best Practices and the Essence of Sustaining Them Beyond the Pandemic

Implementing a range of best practices by Member States and global partners enhanced the efficiency and effectiveness of various forms of regulatory approvals and clearances for COVID-19 vaccines. This study has revealed various best practices that resulted in better handling of multiple processes, products, personnel, and other resources while ensuring higher levels of preparedness for future public health emergencies. It is essential to note that the shorter approval timelines among most Member States were not just because of the emergency but rather the outcomes of well-structured best practices. The shorter vaccine approval times also emphasize the role of the WHO’s EULs, structured reliance mechanisms, and emergency preparedness plans in facilitating the timely approval of vaccines globally [20,21,26]. Other studies have stressed the need for platform technology, effective multi-sectoral stakeholder coordination, and strengthening regulatory systems to streamline approval processes and ensure supply chain continuity in emergencies [23,35,36,37]. Moreover, regulatory agencies should work toward institutionalizing the best practices adopted during the pandemic for more resilient and adaptive regulatory systems for higher regulatory efficiency [21,24,26].

Overall, the findings indicate a significant shift in health product regulation theory and practice, emphasizing balancing speed with scientific validity. This necessitates the creation of thorough provisions for emergency preparedness, regulatory reliance, and administrative flexibility in regulatory practices worldwide.

4.6. Lessons Learned: Integrating Key Insights

Responding to the COVID-19 vaccine revealed that, without proper coordination, global regulatory efforts can become disjointed and delayed. Allocations driven by donors sometimes overlooked national preparedness, highlighting the need for shared standards and respect for the local regulatory authority. To balance timely access with proper procedures, emergency frameworks must uphold confidentiality, inclusion, and transparency. Flexible resource models and partnerships established before a crisis prove essential, demonstrating that resilience depends not only on systems but also on relationships built in advance.

4.7. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, some countries did not respond, which limited how well the global representation was captured and possibly distorted the regional insights. Additionally, the analysis focused only on vaccines that received WHO Emergency Use Listing, excluding those approved solely at the national level. As a result, the study did not capture the regulatory approaches and timelines for these nationally approved vaccines, which may have underrepresented the different strategies used during the pandemic. Furthermore, some data from the regulatory authorities was self-reported, which may have been biased or inconsistent.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the strengths and limitations of the existing regulatory frameworks. The WHO’s approach was instrumental in accelerating access to quality-assured COVID-19 vaccines, particularly in LMICs. Despite various challenges, the process demonstrated significant success and confirmed the feasibility of global coordination approaches. Member States must learn from the highlighted findings and strengthen regulatory frameworks to establish and sustain regulatory efficiency during public health emergencies. This includes ensuring greater independence while fostering smooth collaboration with other agencies and relevant stakeholders. On the other hand, the WHO and other global partners should develop and disseminate clear, harmonized guidelines on regulatory preparedness, such as the recently updated WHO guidelines for pandemic vaccines, which have included lessons learned from the pandemic. Moreover, practices around global health governance to secure high-level political support and clarity of international responsibilities should be strengthened.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.O.A.D. and A.K.B.; methodology, R.O.A.D., A.K.B., A.M. and J.D.; software, R.O.A.D. and A.M.; validation, A.K.B., M.V., O.M. and E.N.; formal analysis, R.O.A.D., A.M., M.V. and R.H.S.; investigation, R.O.A.D., A.K.B., A.M. and M.V.; resources, A.K.B. and H.B.S.; data curation, R.O.A.D., A.M., M.V. and J.D.; writing—original draft, R.O.A.D., A.K.B. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.K.B., M.V., J.D., O.M., R.H.S., E.N. and H.B.S.; visualization R.O.A.D. and A.M.; supervision, A.K.B. and H.B.S.; project administration, A.K.B.; funding acquisition, H.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by the World Health Organization.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy/confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the great support of Nelson E. Masota of the School of Pharmacy at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences in Tanzania, who helped with the study design, data collection, and analysis and provided writing and editorial support following Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines. Moreover, the authors extend their sincere thanks to all study participants for providing valuable information throughout the study. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Goniewicz, K.; Burkle, F.M., Jr. Unleashing the global potential of public health: A framework for future pandemic response. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, A.; Huang, R.; Eusebi, C.A.; Shostak, M. A Brief Overview of Emerging Vaccine Technologies for Pandemic Preparedness. Rand Health Q. 2023, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahonkhai, V.; Martins, S.F.; Portet, A.; Lumpkin, M.; Hartman, D. Speeding access to vaccines and medicines in low-and middle-income countries: A case for change and a framework for optimized product market authorization. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines on Regulatory Preparedness for the Oversight of Pandemic or Other Emergency Use Vaccines in Importing Countries; TRS 1054, Annex 2; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.; Goodman, L. Strengthening regulatory systems globally: A crucial step towards pandemic preparedness and response. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e012883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylor, N.W.; Goodman, J.L. Vaccine preparedness for the next influenza pandemic: A regulatory perspective. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Considerations for Evaluation of COVID-19 Vaccines (Revised); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, J.; O’Connell, E.; Kikule, K.; Hafner, T. The WHO Global Benchmarking Tool: A game changer for strengthening national regulatory capacity. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e003181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadem Broojerdi, A.; Baran Sillo, H.; Ostad Ali Dehaghi, R.; Ward, M.; Refaat, M.; Parry, J. The World Health Organization global benchmarking tool an instrument to strengthen medical products regulation and promote universal health coverage. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadem Broojerdi, A.; Alfonso, C.; Ostad Ali Dehaghi, R.; Refaat, M.; Sillo, H.B. Worldwide assessment of low-and middle-income countries’ regulatory preparedness to approve medical products during public health emergencies. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 722872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Benchmarking Tool (GBT) for Evaluation of National Regulatory Systems of Medical Products, Revision VI; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Good reliance practices in the regulation of medical products: High level principles and considerations. In WHO Expert Committee On Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations: Fifty-Fifth Report; Annex 10; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 237–267. [Google Scholar]

- Ngum, N.; Ndomondo-Sigonda, M.; Habonimana, R.; Siyoi, F.; Irasabwa, C.; Ojukwu, J.; Apolinary, F.; Okello, A.; Ahmada, S.; Walker, S. Evaluation of the review models and approval timelines of authorities participating in the East African Medicine Regulatory Harmonisation initiative: Alignment and strategies for moving forward. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1438041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broojerdi, A.K.; Salvati, A.L.; Abdelfattah, M.R.; Dehaghi, R.O.A.; Sillo, H.B.; Gaspar, R. WHO-listed authorities (WLA) framework: Transparent evidence-based approach for promoting regulatory reliance towards increased access to quality-assured medical products. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1467229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborative Registration Procedure for Medical Products. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/regulation-prequalification/regulation-and-safety/facilitated-product-introduction/collaborative-registration-procedure (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Dellepiane, N.; Wood, D. Twenty-five years of the WHO vaccines prequalification programme (1987–2012): Lessons learned and future perspectives. Vaccine 2015, 33, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.; Kim, E. Exploring Future Pandemic Preparedness Through the Development of Preventive Vaccine Platforms and the Key Roles of International Organizations in a Global Health Crisis. Vaccines 2025, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, M.A.; Saltan, B.A.; Saeed, M.R.; Khokhar, H.; Zaidi, A.; Usman, M.; Marzook, F. Unveiling the Emergency Use Authorization of COVID-19 Vaccines: Safety, Efficacy and Public Trust. Fortune J. Health Sci. 2024, 7, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, K.; Kawano, M.; Maeda, H. Comparison of regulatory approval system for medicines in emergency among Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, and China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, I.T.; Vreman, R.A.; Liberti, L.; Garza, M.A. Regulatory reliance pathways during health emergencies: Enabling timely authorizations for COVID-19 vaccines in Latin America. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2023, 46, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolislis, W.R.; De Lucia, M.L.; Dolz, F.; Mo, R.; Nagaoka, M.; Rodriguez, H.; Woon, M.L.; Yu, W.; Kühler, T.C. Regulatory agilities in the time of covid-19: Overview, trends, and opportunities. Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraci, G.; Bernat, J.; Rodier, C.; Acha, V.; Acquah, J.; Beakes-Read, G. Medicinal Product Development and Regulatory Agilities Implemented During the Early Phases of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences and Implications for the Future—An Industry View. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2023, 57, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.; Hildt, E.; Grabski, E.; Sun, Y.; Meyer, H.; Lommel, A.; Keller-Stanislawski, B.; Müller-Berghaus, J.; Cichutek, K. Accelerated development of COVID-19 vaccines: Technology platforms, benefits, and associated risks. Vaccines 2021, 9, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.; Stolk, P.; Tellner, P.; Acha, V.; Montagne, S.; Stöckert, I. Regulatory flexibilities and guidances for addressing the challenges of COVID-19 in the EU: What can we learn from company experiences? Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2022, 56, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshering, D.; Chejor, P. Regulatory flexibilities and access to COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic in Bhutan. Exp. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2022, 7, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, M.M.; Lim, J.C. Pandemic best regulatory practices: An urgent need in the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 108, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimhan, J.; Maanvizhi, S. Regulatory approval pathway for COVID-19 vaccine in USA, Europe and India. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, H.; Endo, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Miyata, H.; Munekage, M.; Taketomi, A.; Kakeji, Y.; Seto, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Yamaue, H. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gastroenterological surgeries in 2020: A study using the National Clinical Database of Japan. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2023, 7, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banoun, H. mRNA: Vaccine or gene therapy? The safety regulatory issues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.P.; Ghimire, T.R.; Subramanya, S.H. Access to and equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccine in low-income countries. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.-J. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination among low-, middle-, and high-income countries: The mediating role of vaccination policy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, L.E.; Hopkins, R.H., Jr.; Broder, K.R.; Lee, G.M.; Edwards, K.M.; Daley, M.F.; Jackson, L.A.; Nelson, J.C.; Riley, L.E.; McNally, V.V. COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical (VaST) Work Group: Enhancing vaccine safety monitoring during the pandemic. Vaccine 2024, 42, 125549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, M.; Hosseinpour, S.; Rezaee-Zavareh, M.S.; Dascalu, S.; Rostamian, S.; Aramesh, K.; Madani, K.; Kordasti, S. A quantitative evaluation of the impact of vaccine roll-out rate and coverage on reducing deaths: Insights from the first 2 years of COVID-19 epidemic in Iran. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duroseau, B.; Kipshidze, N.; Limaye, R.J. The impact of delayed access to COVID-19 vaccines in low-and lower-middle-income countries. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1087138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello, J.S.; Ginindza, T.; Nyerere, J. Protocol: Multi-Sectoral Coordination during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Practices, Challenges, and Recommendations for Future Preparedness-A Systematic Literature Review Protocol. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Kalra, K.; Phelan, A.L. Expanding global vaccine manufacturing capacity: Strategic prioritization in small countries. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0002098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccaro, A.; Audia, C.; Stokes, K.; Masud, H.; Sekalala, S.; Pecchia, L.; Piaggio, D. Pandemic Preparedness: A Scoping Review of Best and Worst Practices from COVID-19. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).