Socioeconomic Barriers to COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in Southern Italy: A Retrospective Study to Evaluate Association with the Social and Material Vulnerability Index in Apulia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context and Definition of the First Booster Dose

2.2. Study Design and Data Sources

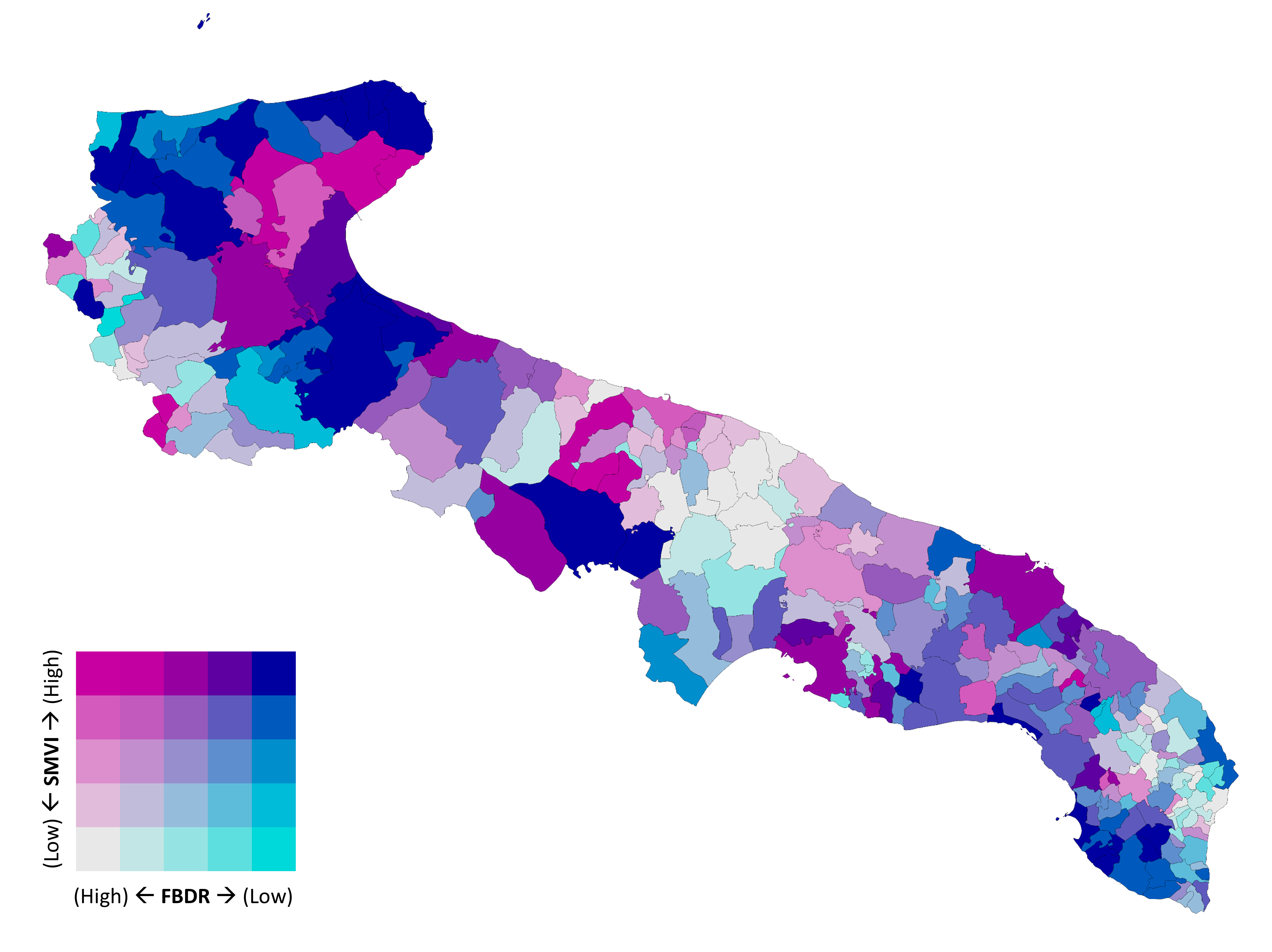

2.3. Socioeconomic Deprivation

- Incidence of single-parent households (young < 35 years, or adult 35–64 years).

- Incidence of households with six or more members.

- Proportion of individuals aged 25–64 years with no educational qualification or illiteracy.

- Incidence of households composed only of elderly members (≥65 years) including at least one aged ≥80 years.

- Severe overcrowding, defined as households with more occupants than allowed by dwelling size.

- Proportion of young people (15–29 years) not in education, employment, or training (NEET).

- Incidence of households with children in which no adult is employed or retired from previous employment.

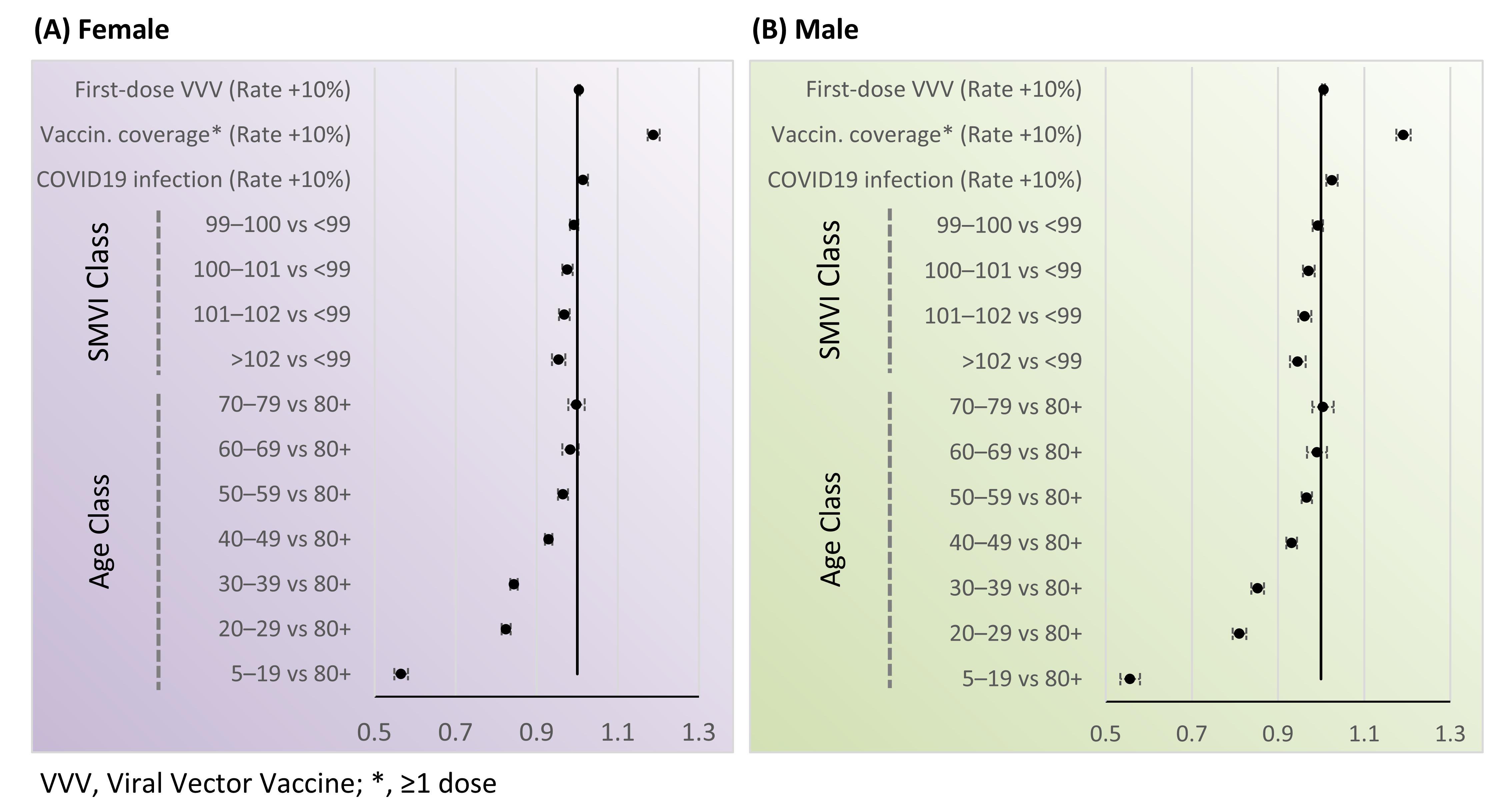

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- -

- Age group; reference: ≥80 years.

- -

- Socioeconomic deprivation (SMVI) categorized into quartiles to reflect typical epidemiologic use; reference: lowest deprivation (<99).

- -

- Municipal SARS-CoV-2 infection rate, included as a context-level determinant of risk perception.

- -

- Vaccination coverage rate (≥1 dose), included as a marker of local vaccination behavior and access.

- -

- First dose viral vector vaccine rate, to account for early-phase vaccine allocation differences across municipalities.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISTAT | Italian Institute of Statistics |

| SMVI | Social and Material Vulnerability Index |

References

- COVID-19 Cases|WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Datadot. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/02/23/20G00020/s (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Chen, Y.-T. Effect of vaccination patterns and vaccination rates on the spread and mortality of the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Technol. 2023, 12, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Huang, H.; Ju, J.; Sun, R.; Zhang, J. Impact of vaccination on the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. states. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garduño-Orbe, B.; Palma-Ramírez, P.S.; López-Ortiz, E.; García-Morales, G.; Sánchez-Rebolledo, J.M.; Emigdio-Loeza, A.; Gómez-García, A.; López-Ortiz, G. Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Hospitalization and Mortality: A Comparative Analysis of Clinical Outcomes During the Early Phase of the Pandemic. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2025, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadas, S.M.; Vilches, T.N.; Zhang, K.; Wells, C.R.; Shoukat, A.; Singer, B.H.; Meyers, L.A.; Neuzil, K.M.; Langley, J.M.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; et al. The Impact of Vaccination on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreaks in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havers, F.P.; Pham, H.; Taylor, C.A.; Whitaker, M.; Patel, K.; Anglin, O.; Kambhampati, A.K.; Milucky, J.; Zell, E.; Moline, H.L.; et al. COVID-19-Associated Hospitalizations Among Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Adults 18 Years or Older in 13 US States, January 2021 to April 2022. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rief, W. Fear of Adverse Effects and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Recommendations of the Treatment Expectation Expert Group. JAMA Health Forum 2021, 2, e210804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankenthal, D.; Zatlawi, M.; Karni-Efrati, Z.; Keinan-Boker, L.; Glatman-Freedman, A.; Bromberg, M. Evaluation of adverse events and comorbidity exacerbation following the COVID-19 booster dose: A national survey among randomly-selected booster recipients. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razai, M.S.; Chaudhry, U.A.R.; Doerholt, K.; Bauld, L.; Majeed, A. Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy. BMJ 2021, 373, n1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. How cognitive biases affect our interpretation of political messages. BMJ 2010, 340, c2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Singh, A.K.; Wagner, A.L.; Boulton, M.L. Mapping the Cognitive Biases Related to Vaccination: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggeri, K.; Vanderslott, S.; Yamada, Y.; Argyris, Y.A.; Većkalov, B.; Boggio, P.S.; Fallah, M.P.; Stock, F.; Hertwig, R. Behavioural interventions to reduce vaccine hesitancy driven by misinformation on social media. BMJ 2024, 384, e076542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taubert, F.; Meyer-Hoeven, G.; Schmid, P.; Gerdes, P.; Betsch, C. Conspiracy narratives and vaccine hesitancy: A scoping review of prevalence, impact, and interventions. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, B.K.A. Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Positive Views of Science Continue to Decline. Pew Research Center. 2023. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/11/14/americans-trust-in-scientists-positive-views-of-science-continue-to-decline/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Robinson, E.; Jones, A.; Lesser, I.; Daly, M. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2024–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, M.V.; Bubar, K.M.; Maldonado, Y.; Hotez, P.J.; Lo, N.C. Modeling Reemergence of Vaccine-Eliminated Infectious Diseases Under Declining Vaccination in the US. JAMA 2025, 333, 2176–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambi, C.; Fabiani, M.; D’Ancona, F.; Ferrara, L.; Fiacchini, D.; Gallo, T.; Martinelli, D.; Pascucci, M.G.; Prato, R.; Filia, A.; et al. Parental vaccine hesitancy in Italy—Results from a national survey. Vaccine 2018, 36, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, V.; Madio, L.; Principe, F. Vaccine hesitancy and (fake) news: Quasi-experimental evidence from Italy. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, J.; Bakshi, S.; Wasim, A.; Ahmad, M.; Majid, U. What factors promote vaccine hesitancy or acceptance during pandemics? A systematic review and thematic analysis. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daab105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, Y.M.; Choi, J.; Cuccaro, P.M.; Martinez, J.; Xie, J.; Owens, M.; Yamal, J.-M. Sociodemographic and health-related predictors of COVID-19 booster uptake among fully vaccinated adults. Vaccine 2025, 54, 127048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmuir, T.; Wilson, M.; McCleary, N.; Patey, A.M.; Mekki, K.; Ghazal, H.; Estey Noad, E.; Buchan, J.; Dubey, V.; Galley, J.; et al. Strategies and resources used by public health units to encourage COVID-19 vaccination among priority groups: A behavioural science-informed review of three urban centres in Canada. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, K.; Mahabir, R.; Gkountouna, O.; Crooks, A.; Croitoru, A. Understanding the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in the United States: A comparison of social surveys and social media. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Polla, G.; del Giudice, G.M.; Folcarelli, L.; Napoli, A.; Angelillo, I.F. Willingness to accept a second COVID-19 vaccination booster dose among healthcare workers in Italy. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1051035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folcarelli, L.; del Giudice, G.M.; Corea, F.; Angelillo, I.F. Intention to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Dose in a University Community in Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primieri, C.; Bietta, C.; Giacchetta, I.; Chiavarini, M.; de Waure, C. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance or hesitancy in Italy: An overview of the current evidence. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2023, 59, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Misure Della Vulnerabilità: Un’applicazione a Diversi Ambiti Territoriali. Available online: https://www.istat.it/produzione-editoriale/le-misure-della-vulnerabilita-unapplicazione-a-diversi-ambiti-territoriali/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Larson, H.J.; Gakidou, E.; Murray, C.J.L. The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry of Health. (27 September 2021) Circular no. 43604: COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign-Administration of the First Booster Dose. Available online: https://www.certifico.com/news/circolare-ministero-della-salute-n-0043604-del-27-settembre-2021 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Italian Ministry of Health. (22 November 2021) Circular no. 53312: COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign-Update on the Interval Between Primary Vaccination and Booster Dose. Available online: https://www.certifico.com/news/circolare-ministero-della-salute-n-53312-del-22-novembre-2021 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Italian Ministry of Health. (24 December 2021) Circular no. 59207: Extension of the COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign and Update on Booster Dose Administration. Available online: https://certifico.com/news/circolare-min-salute-n-0059207-del-24-dicembre-2021 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Go. Data. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/godata (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- ISTAT-Demo Istat. Available online: https://demo.istat.it (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Vallée, A. Geoepidemiological perspective on COVID-19 pandemic review, an insight into the global impact. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1242891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.-Q. Geographical Analysis of COVID-19 Epidemiology: A Review. Int. J. Sci. Healthc. Res. 2023, 8, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, D. Using the COVID-19 Symptom Survey to Track Vaccination Uptake and Sentiment in the United States 2021. Available online: https://delphi.cmu.edu/blog/2021/01/28/using-the-covid-19-symptom-survey-to-track-vaccination-uptake-and-sentiment-in-the-united-states/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Smith, C.D. Incorporating Geographic Information Science and Technology in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2020, 17, E58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmelle, E.; Bearman, N.; Yao, X.A. Developing geospatial analytical methods to explore and communicate the spread of COVID19. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 51, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, P.H.; Patten, C.A.; Wi, C.-I.; Bublitz, J.T.; Ryu, E.; Ristagno, E.H.; Juhn, Y.J. Role of geographic risk factors and social determinants of health in COVID-19 epidemiology: Longitudinal geospatial analysis in a midwest rural region. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Center for Forecasting and Outbreak Analytics 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/forecast-outbreak-analytics/index.html (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Lee, J.; Huang, Y. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: The Role of Socioeconomic Factors and Spatial Effects. Vaccines 2022, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupu, D.; Tiganasu, R. Does education influence COVID-19 vaccination? A global view. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, S.; Tanasković, S. Socioeconomic determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2024, 24, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, T.P.G.P.H. Correction: Determinants of Covid-19 vaccination: Evidence from the US pulse survey. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0002425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.; Michalski, N.; Bartig, S.; Wulkotte, E.; Poethko-Müller, C.; Graeber, D.; Rosario, A.S.; Hövener, C.; Hoebel, J. Reconsidering inequalities in COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Germany: A spatiotemporal analysis combining individual educational level and area-level socioeconomic deprivation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardavas, C.; Nikitara, K.; Aslanoglou, K.; Lagou, I.; Marou, V.; Phalkey, R.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Fernandez, E.; Vivilaki, V.; Kamekis, A.; et al. Social determinants of health and vaccine uptake during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 35, 102319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health, D. and A. Socioeconomic Determinants of Vaccine Uptake—July 2021 to January 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/socioeconomic-determinants-of-vaccine-uptake-july-2021-to-january-2022?language=en (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Morales, D.X.; Beltran, T.F.; Morales, S.A. Gender, socioeconomic status, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the US: An intersectionality approach. Sociol. Health Illn. 2022, 44, 953–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyesus, A.; Tesfay, K. Effect of maternal education on completing childhood vaccination in Ethiopia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Srivastav, A.; Vashist, K.; Black, C.L.; Kriss, J.L.; Hung, M.-C.; Meng, L.; Zhou, T.; Yankey, D.; Masters, N.B.; et al. COVID-19 Booster Dose Vaccination Coverage and Factors Associated with Booster Vaccination among Adults, United States, March 2022. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihongbe, T.O.; Kim, J.-E.C.; Dahlen, H.; Kranzler, E.C.; Seserman, K.; Moffett, K.; Hoffman, L. Trends in primary, booster, and updated COVID-19 vaccine readiness in the United States, January 2021–April 2023: Implications for 2023–2024 updated COVID-19 vaccines. Prev. Med. 2024, 180, 107887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majid, U.; Ahmad, M.; Zain, S.; Akande, A.; Ikhlaq, F. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance: A comprehensive scoping review of global literature. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daac078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, H.; Harmon, N.; Martin, J.; Olaco, C.-A.; Netski, D.M.; Batra, K. Community Level Correlates of COVID-19 Booster Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Vaccines 2024, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Bonett, S.; Oyiborhoro, U.; Aryal, S.; Kornides, M.; Glanz, K.; Villarruel, A.; Bauermeister, J. Factors associated with the COVID-19 booster vaccine intentions of young adults in the United States. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2383016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, E.; Cartledge, S.; Damery, S.; Greenfield, S. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic; a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odziemczyk-Stawarz, I.; Perek-Białas, J. What may influence older Europeans’ decision about the seasonal influenza vaccine? A literature review of socio-cultural and psycho-social factors related to seasonal influenza vaccination uptake. Vaccine 2025, 61, 127265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Prado, E.; Suárez-Sangucho, I.A.; Vasconez-Gonzalez, J.; Santillan-Roldán, P.A.; Villavicencio-Gomezjurado, M.; Salazar-Santoliva, C.; Tello-De-la-Torre, A.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S. Pandemic paradox: How the COVID-19 crisis transformed vaccine hesitancy into a two-edged sword. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2543167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, N.; Edwards, B.; Gray, M.; Hiscox, M.; McEachern, S.; Sollis, K. Data trust and data privacy in the COVID-19 period. Data Policy 2022, 4, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomeo, N.; Lorusso, L.; Trerotoli, P. Validity Of Socioeconomic Inequality Indices over Time in Public Health Research: A Case Study on Ivsm and Maternal Data. Epidemiol. Biostat. Public Health 2025, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Individuals with ≥1 COVID-19 vaccine dose | 3,472,095 |

| Age (years) | Range: 5–110 |

| Sex | Female: 51.6%; Male: 48.4% |

| Total vaccine doses administered | 9,614,640 |

| Individuals receiving ≥1 booster dose | 2,732,258 |

| First booster dose rate (FBDR) | 78.7% among individuals with ≥1 dose |

| Municipalities included | 257 |

| Median municipal FBDR [IQR] | 72.3% [69.3–75.7%] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartolomeo, N.; Lorusso, L.; Maldera, N.; Trerotoli, P. Socioeconomic Barriers to COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in Southern Italy: A Retrospective Study to Evaluate Association with the Social and Material Vulnerability Index in Apulia. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1255. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121255

Bartolomeo N, Lorusso L, Maldera N, Trerotoli P. Socioeconomic Barriers to COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in Southern Italy: A Retrospective Study to Evaluate Association with the Social and Material Vulnerability Index in Apulia. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1255. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121255

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartolomeo, Nicola, Letizia Lorusso, Niccolò Maldera, and Paolo Trerotoli. 2025. "Socioeconomic Barriers to COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in Southern Italy: A Retrospective Study to Evaluate Association with the Social and Material Vulnerability Index in Apulia" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1255. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121255

APA StyleBartolomeo, N., Lorusso, L., Maldera, N., & Trerotoli, P. (2025). Socioeconomic Barriers to COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in Southern Italy: A Retrospective Study to Evaluate Association with the Social and Material Vulnerability Index in Apulia. Vaccines, 13(12), 1255. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121255