Integrated In Silico and In Vivo Evaluation of a Tetravalent SARS-CoV-2 RBD–Fc Fusion Vaccine with Broad Cross-Variant Antibody Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Silico Immune Simulation

2.2. Plasmid Construction

2.3. Expression and Purification of Tetravalent RBD–Fc

2.4. Protein Quantification, SDS–PAGE, and ACE2–Fc Western Blot

2.5. Animals and Immunization

2.6. ELISA for RBD Binding and Cross-Reactivity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

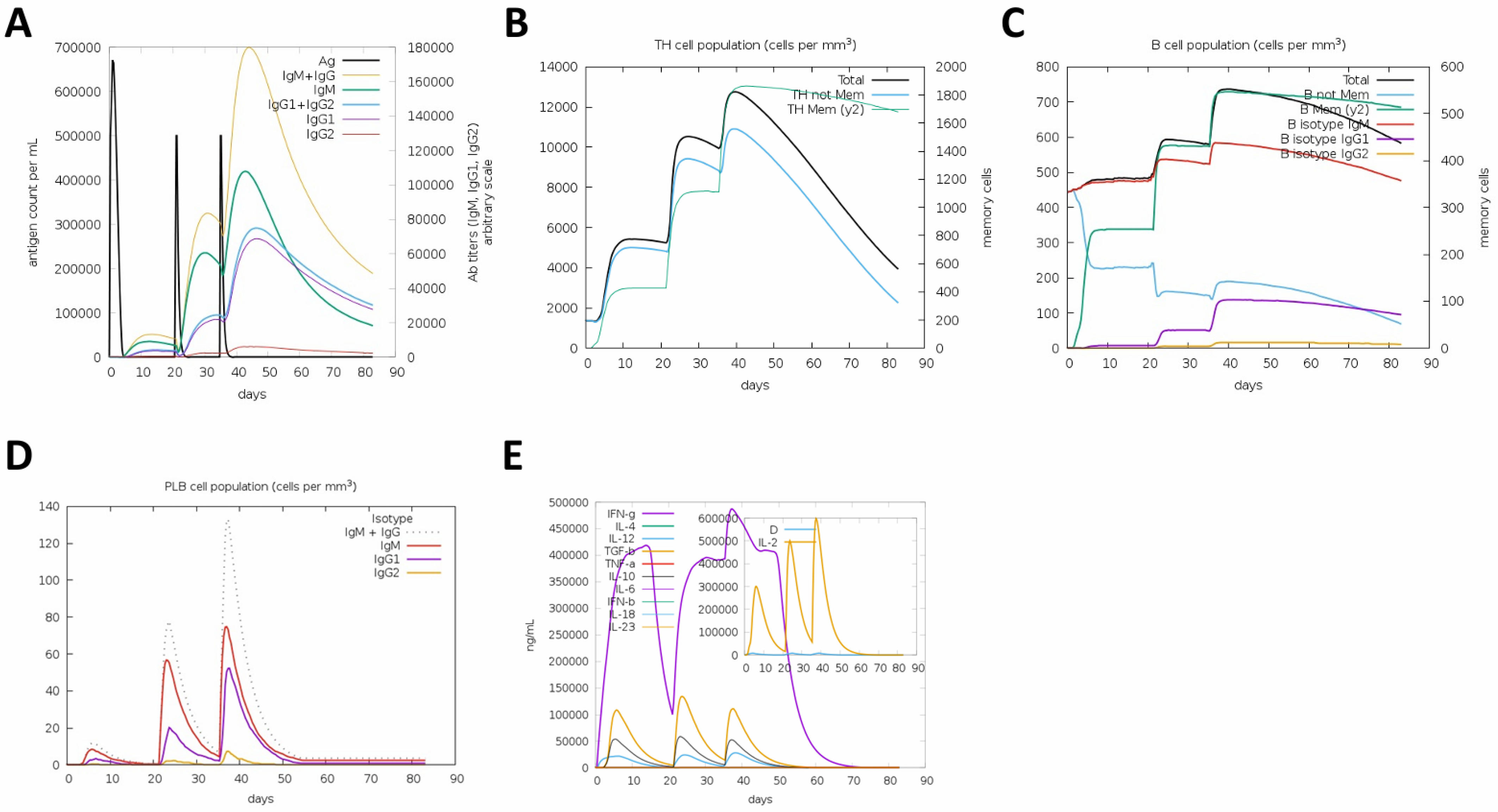

3.1. In Silico Prediction of Immune Responses Induced by the Tetravalent RBD–Fc Vaccine

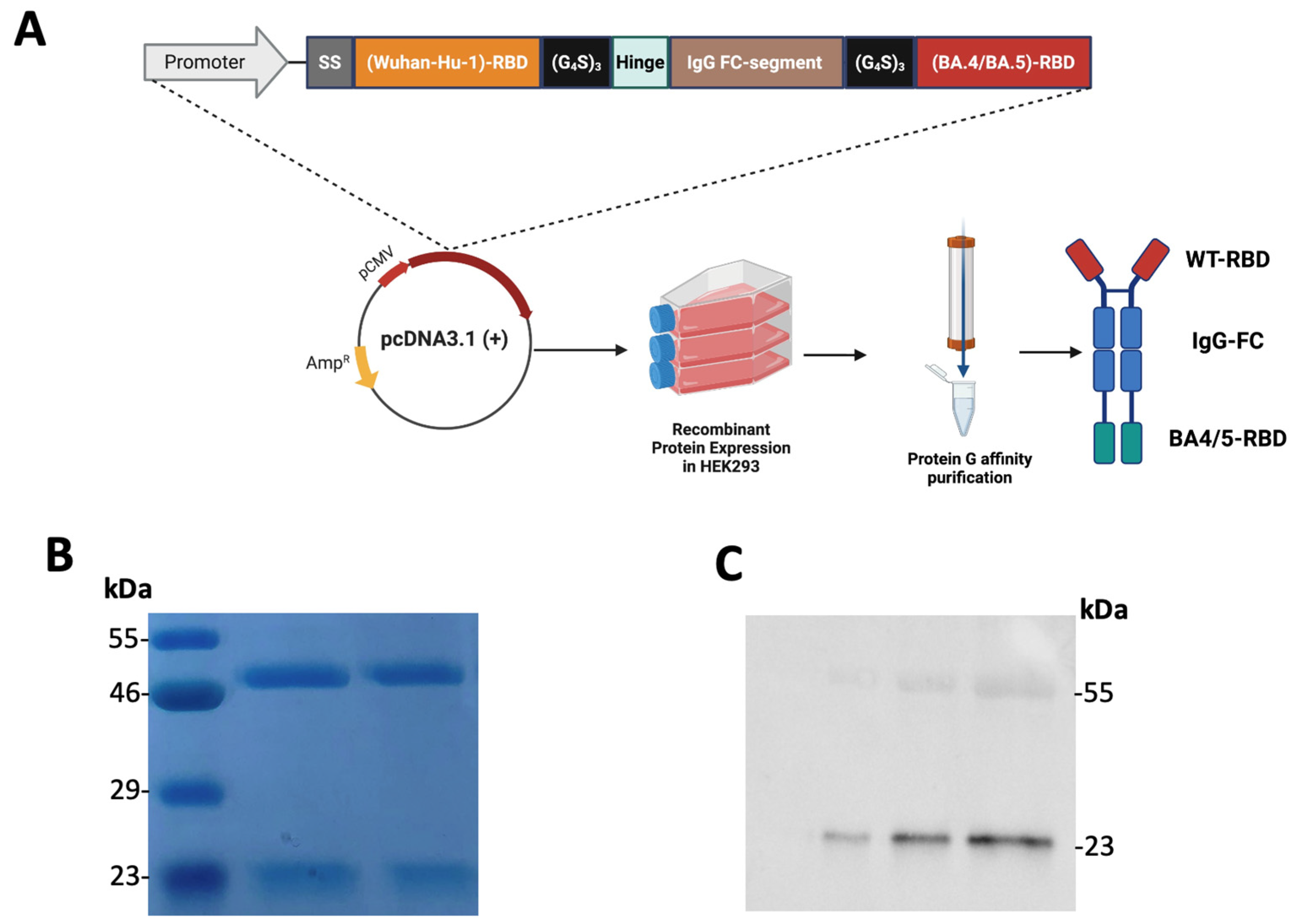

3.2. Construction, Expression, and Purification of the Recombinant Tetravalent RBD–Fc Fusion Vaccine

3.3. In Vivo Evaluation of Serum Antibody Responses Following Tetravalent RBD–Fc Vaccination

3.4. Cross-Reactive Binding of Vaccinated Mouse Sera to SARS-CoV-2 RBD Variants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| RBD | Receptor-binding domain |

| Fc | Fragment crystallizable region |

| SDS–PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine |

| WT | Wild type |

| MWCO | Molecular weight cut-off |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus promoter |

| OD450 | Optical density at 450 nm |

| HEK293 | Human embryonic kidney 293 cells |

| C-ImmSim | Computational Immune Simulation Platform |

References

- Wang, L.; Xiang, Y. Spike Glycoprotein-Mediated Entry of SARS Coronaviruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, B.J.; Jiang, S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV—A target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabidi, N.Z.; Liew, H.L.; Farouk, I.A.; Puniyamurti, A.; Yip, A.J.W.; Wijesinghe, V.N.; Low, Z.Y.; Tang, J.W.; Chow, V.T.K.; Lal, S.K. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Implications on Immune Escape, Vaccination, Therapeutic and Diagnostic Strategies. Viruses 2023, 15, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.L.; Meher, J.; Giri, A.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Mohapatra, E.; Ruikar, M.M.; Rao, D. RBD mutations at the residues K417, E484, N501 reduced immunoreactivity with antisera from vaccinated and COVID-19 recovered patients. Drug Target Insights 2024, 18, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, J.E.; Addetia, A.; Dang, H.V.; Stewart, C.; Brown, J.T.; Sharkey, W.K.; Sprouse, K.R.; Walls, A.C.; Mazzitelli, I.G.; Logue, J.K.; et al. Omicron spike function and neutralizing activity elicited by a comprehensive panel of vaccines. Science 2022, 377, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.Y.; To, A.; Wong, T.A.S.; Lieberman, M.M.; Clements, D.E.; Senda, J.T.; Ball, A.H.; Pessaint, L.; Andersen, H.; Furuyama, W.; et al. Recombinant protein subunit SARS-CoV-2 vaccines formulated with CoVaccine HT adjuvant induce broad, Th1 biased, humoral and cellular immune responses in mice. Vaccine X 2021, 9, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, N.; Kumar, S.; Rajmani, R.S.; Singh, R.; Lemoine, C.; Jakob, V.; Bj, S.; Jagannath, N.; Bhat, M.; Chakraborty, D.; et al. Enhanced protective efficacy of a thermostable RBD-S2 vaccine formulation against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xu, F.; Lu, H.; Yao, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, Z. Development of an RBD-Fc fusion vaccine for COVID-19. Vaccine X 2024, 16, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab, D.H. Vaccinal antibodies: Fc antibody engineering to improve the antiviral antibody response and induce vaccine-like effects. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 5532–5545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feitsma, E.A.; Janssen, Y.F.; Boersma, H.H.; van Sleen, Y.; van Baarle, D.; Alleva, D.G.; Lancaster, T.M.; Sathiyaseelan, T.; Murikipudi, S.; Delpero, A.R.; et al. A randomized phase I/II safety and immunogenicity study of the Montanide-adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-RBD-Fc vaccine, AKS-452. Vaccine 2023, 41, 2184–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, S.L.; Zu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.-K.; Wang, W.; Xiao, G. A novel RSV F-Fc fusion protein vaccine reduces lung injury induced by respiratory syncytial virus infection. Antivir. Res. 2019, 165, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, S.; Ren, J.; Phapugrangkul, P.; Colaco, C.A.; Bailey, C.R.; Shelton, H.; Molesti, E.; Temperton, N.J.; Barclay, W.S.; Jones, I.M. Adjuvant-free immunization with hemagglutinin-Fc fusion proteins as an approach to influenza vaccines. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Kou, Z.; Ma, C.; Tao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y.; Yu, F.; Tseng, C.T.K.; Zhou, Y.; et al. A truncated receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein potently inhibits MERS-CoV infection and induces strong neutralizing antibody responses: Implication for developing therapeutics and vaccines. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkkemper, M.; Veth, T.S.; Brouwer, P.J.M.; Turner, H.; Poniman, M.; Burger, J.A.; Bouhuijs, J.H.; Olijhoek, W.; Bontjer, I.; Snitselaar, J.L.; et al. Co-display of diverse spike proteins on nanoparticles broadens sarbecovirus neutralizing antibody responses. iScience 2022, 25, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, M.C.; Kepl, E.; Navarro, M.J.; Chen, C.; Johnson, M.; Sprouse, K.R.; Stewart, C.; Palser, A.; Valdez, A.; Pettie, D.; et al. Potent neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 variants by RBD nanoparticle and prefusion-stabilized spike immunogens. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, K.; Chai, Y.; Luo, T.; Dai, L.; Gao, G.F. Mosaic RBD nanoparticle elicits immunodominant antibody responses across sarbecoviruses. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Gao, P.; Liu, S.; Lu, S.; Lei, W.; Zheng, T.; Liu, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, S.; et al. Protective prototype-Beta and Delta-Omicron chimeric RBD-dimer vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 2022, 185, 2265–2278.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, L.A.; Pueblas Castro, C.; Demaría, A.; Prado, L.; Cassero, C.G.F.; Saposnik, L.M.; Córdoba, F.P.; Rodriguez, J.M.; Piccini, G.; Antonelli, R.; et al. Development of bivalent RBD adapted COVID-19 vaccines for broad sarbecovirus immunity. npj Vaccines 2025, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehmani, M.B.I.; Arshad, F.; Khan, M.U.; Ejaz, H.; Nishan, U.; Alotaibi, A.; Ullah, R.; Chen, K.; Ojha, S.C.; Shah, M. Computational design of an mRNA vaccine targeting antifungal-resistant Lomentospora prolificans. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Cao, Y.; Li, R.; Zheng, K.; Wu, X. A comprehensive strategy for the development of a multi-epitope vaccine targeting Treponema pallidum, utilizing heat shock proteins, encompassing the entire process from vaccine design to in vitro evaluation of immunogenicity. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1551437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahmoud, A.B.; Alhamawi, R.M.; Taher, M.Y.; Alsubhi, A.S.; Abouzied, M.M.; Zahid, H.M.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Almarghalani, N.; Alotaibi, K.; Habash, A.; et al. Integrated In Silico and In Vivo Evaluation of a Tetravalent SARS-CoV-2 RBD–Fc Fusion Vaccine with Broad Cross-Variant Antibody Responses. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121244

Mahmoud AB, Alhamawi RM, Taher MY, Alsubhi AS, Abouzied MM, Zahid HM, Alotaibi MA, Almarghalani N, Alotaibi K, Habash A, et al. Integrated In Silico and In Vivo Evaluation of a Tetravalent SARS-CoV-2 RBD–Fc Fusion Vaccine with Broad Cross-Variant Antibody Responses. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121244

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmoud, Ahmad Bakur, Renad M. Alhamawi, Mustafa Yassin Taher, Awadh S. Alsubhi, Mekky M. Abouzied, Heba M. Zahid, Mohammed Abdullah Alotaibi, Nada Almarghalani, Khulood Alotaibi, Abdulrahman Habash, and et al. 2025. "Integrated In Silico and In Vivo Evaluation of a Tetravalent SARS-CoV-2 RBD–Fc Fusion Vaccine with Broad Cross-Variant Antibody Responses" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121244

APA StyleMahmoud, A. B., Alhamawi, R. M., Taher, M. Y., Alsubhi, A. S., Abouzied, M. M., Zahid, H. M., Alotaibi, M. A., Almarghalani, N., Alotaibi, K., Habash, A., Alsharif, S. A., & Alkayyal, A. (2025). Integrated In Silico and In Vivo Evaluation of a Tetravalent SARS-CoV-2 RBD–Fc Fusion Vaccine with Broad Cross-Variant Antibody Responses. Vaccines, 13(12), 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121244