Incidence, Clinical Features, and Vaccination Coverage of Pneumococcal Disease in People Living with HIV: A Retrospective Cohort Study (2015–2024)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLWH | people living with HIV |

| VL | viral load |

| PD | pneumococcal disease |

| MSM | men who have sex with men |

| IDU | intravenous drug use |

| ART | antiretroviral treatment |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| IPD | invasive pneumococcal disease |

| PPSV23 | 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine |

| PCV13 | 13-valent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine |

| PCV15 | 15-valent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine |

| PCV20 | 20-valent pneumococcal conjugated vaccine |

References

- Navarro-Torné, A.; Montuori, E.A.; Kossyvaki, V.; Méndez, C. Burden of pneumococcal disease among adults in Southern Europe (Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 3670–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soneira, M.S.; Del-Águila-Mejía, J.; Acosta-Gutiérrez, M.; Sastre-García, M.; Amillategui-Dos-Santos, R.; Portero, R.C. Enfermedad Neumocócica Invasiva en España en 2023. Bol. Epidemiol. Sem. 2024, 32, 74–93. Available online: https://revista.isciii.es/index.php/bes/article/view/1381 (accessed on 27 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Garrido, H.M.G.; Mak, A.M.R.; Wit, F.W.N.M.; Wong, G.W.M.; Knol, M.J.; Vollaard, A.; Tanck, M.W.T.; Van Der Ende, A.; Grobusch, M.P.; Goorhuis, A. Incidence and Risk Factors for Invasive Pneumococcal Disease and Community-acquired Pneumonia in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals in a High-income Setting. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, P.D.; Amin-Chowdhury, Z.; E Croxford, S.; Sheppard, C.; Fry, N.; Delpech, V.C.; Ladhani, S.N. Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in People with Human Immunodeficiency Virus in England, 1999–2017. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillóniz, C.; Torres, A.; Manzardo, C.; Gabarrús, A.; Ambrosioni, J.; Salazar, A.; García, F.; Ceccato, A.; Mensa, J.; de la Bella Casa, J.P.; et al. Community-Acquired Pneumococcal Pneumonia in Virologically Suppressed HIV-Infected Adult Patients: A Matched Case-Control Study. Chest 2017, 152, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Working Group on Vaccinations of the Spanish Society of Epidemiology. Guide on Pneumococcal Disease and Its Vaccines; SEE: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Available online: https://seepidemiologia.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/GUI%CC%81A-NEUMOCOCO-1-1-1.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Horberg, M.; Thompson, M.; Agwu, A.; Colasanti, J.; Haddad, M.; Jain, M.; McComsey, G.; Radix, A.; Rakhmanina, N.; Short, W.R.; et al. Primary Care Guidance for Providers of Care for Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: 2024 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmedt, N.; Schiffner-Rohe, J.; Sprenger, R.; Walker, J.; von Eiff, C.; Häckl, D. Pneumococcal vaccination rates in immunocompromised patients-A cohort study based on claims data from more than 200,000 patients in Germany. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejlersen, E.W.; Loft, J.A.; Gelpi, M.; Heidari, S.-L.; Rezahosseini, O.; Poulsen, J.R.; Møller, D.L.; Harboe, Z.B.; Benfield, T.; Nielsen, S.D.; et al. Incidence of Confirmed Influenza and Pneumococcal Infections and Vaccine Uptake Among Virologically Suppressed People Living with HIV. Vaccines 2025, 13, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Gondar, O.; Torras-Vives, V.; de Diego-Cabanes, C.; Satué-Gracia, E.M.; Vila-Rovira, A.; Forcadell-Perisa, M.J.; Ribas-Seguí, D.; Rodríguez-Casado, C.; Vila-Córcoles, A. Incidence and risk factors of pneumococcal pneumonia in adults: A population-based study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbà, J.; Marsà, A. Hospital incidence, in-hospital mortality and medical costs of pneumococcal disease in Spain (2008–2017): A retrospective multicentre study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2021, 37, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishna, S.; Wolfensberger, A.; Kachalov, V.; A Roth, J.; Kusejko, K.; Scherrer, A.U.; Furrer, H.; Hauser, C.; Calmy, A.; Cavassini, M.; et al. Decreasing Incidence and Determinants of Bacterial Pneumonia in People With HIV: The Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, M.S.; Ward, J.W.; Hanson, D.L.; Jones, J.L.; Kaplan, J.E. Pneumococcal disease among human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons: Incidence, risk factors, and impact of vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyos, S.; Berrocal, L.; González-Cordón, A.; Inciarte, A.; de la Mora, L.; Martínez-Rebollar, M.; Laguno, M.; Fernández, E.; Ambrosioni, J.; Chivite, I.; et al. Sex-based epidemiological and immunovirological characteristics of people living with HIV in current follow-up at a tertiary hospital: A comparative retrospective study, Catalonia, Spain, 1982 to 2020. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28, 2200317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, J.C.; A Corcorran, M.; Carney, T.; Parczewski, M.; Gandhi, M. The impact of homelessness and housing insecurity on HIV. Lancet HIV 2025, 12, e449–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Wan, Z.; Kilby, A.; Kilby, J.M.; Jiang, W. Humoral immune responses to Streptococcus pneumoniae in the setting of HIV-1 infection. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4430–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huson, M.A.M.; Stolp, S.M.; Van Der Poll, T.; Grobusch, M.P. Community-acquired bacterial bloodstream infections in HIV-infected patients: A systematic review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reekie, J.; Gatell, J.M.; Yust, I.; Bakowska, E.; Rakhmanova, A.; Losso, M.; Krasnov, M.; Francioli, P.; Kowalska, J.D.; Mocroft, A. Fatal and nonfatal AIDS and non-AIDS events in HIV-1-positive individuals with high CD4 cell counts according to viral load strata. AIDS 2011, 25, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Invasive Pneumococcal Disease—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2022; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2025; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/invasive-pneumococcal-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2022 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Gil-Prieto, R.; Hernandez-Barrera, V.; Marín-García, P.; González-Escalada, A.; Gil-De-Miguel, Á. Hospital burden of pneumococcal disease in Spain (2016–2022): A retrospective study. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2025, 21, 2437915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moioffer, S.J.; Danahy, D.B.; van de Wall, S.; Jensen, I.J.; Sjaastad, F.V.; Anthony, S.M.; Harty, J.T.; Griffith, T.S.; Badovinac, V.P. Severity of Sepsis Determines the Degree of Impairment Observed in Circulatory and Tissue-Resident Memory CD8 T Cell Populations. J. Immunol. 2021, 207, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Matanock, A.; Xing, W.; Adih, W.K.M.; Li, J.D.; Gierke, R.; Almendares, O.M.; Reingold, A.; Alden, N.; Petit, S.; et al. Impact of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine on Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Among Adults With HIV-United States, 2008–2018. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 90, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Córcoles, A.; Ochoa-Gondar, O.; de Diego, C.; Satué, E.; Vila-Rovira, A.; Aragón, M. Pneumococcal vaccination coverages by age, sex and specific underlying risk conditions among middle-aged and older adults in Catalonia, Spain, 2017. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1800446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, H.M.G.; Schnyder, J.L.; Haydari, B.; Vollaard, A.M.; Tanck, M.W.; de Bree, G.J.; Meek, B.; Grobusch, M.P.; Goorhuis, A. Immunogenicity of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine followed by the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in people living with HIV on combination antiretroviral therapy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2022, 60, 106629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaru, J.; Bahuaud, M.; Lejeune, G.; Hentzien, M.; Berger, J.-L.; Robbins, A.; Lebrun, D.; N’gUyen, Y.; Bani-Sadr, F.; Batteux, F.; et al. Single-Dose 13-Valent Conjugate Pneumococcal Vaccine in People Living With HIV—Immunological Response and Protection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 791147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Cheong, H.J.; Noh, J.Y.; Choi, M.J.; Yoon, J.G.; Kim, W.J. Immunogenicity and safety of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in HIV-infected adults in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: Analysis stratified by CD4 T-cell count. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Cases (n = 148) | Controls (n = 8499) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex at birth, n(%) | 0.004 | ||

| Male | 118 (80) | 7446 (88) | |

| Female | 30 (20) | 1053 (12) | |

| Age at first episode, median (IQR) | 45.9 (36.1–53.3) | -- | |

| Birthplace, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| Spain | 89 (64) | 3865 (48) | |

| Other | 50 (36) | 4172 (52) | |

| Sexual orientation, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| MSM | 55 (50) | 5550 (73) | |

| Heterosexual | 50 (45) | 1643 (22) | |

| Bisexual | 6 (5) | 438 (6) | |

| Transmission mode, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| Sexual | 101 (70) | 7570 (90) | |

| IDU | 41 (28) | 735 (9) | |

| Transfusion | 0 (0) | 32 (<1) | |

| Vertical | 3 (2) | 31 (<1) | |

| CD4 nadir, median (IQR) | 181 (58–324) | 322 (183–496) | <0.001 |

| HIV VL peak (cp/mL), median (IQR) | 176,839 (20,900–502,000) | 37,333 (450–189,900) | <0.001 |

| Years between HIV+ and PD, median (IQR) | 12.4 (2.5–21.5) | -- | |

| Years between ART start and PD, median (IQR) | 4.8 (0–15.8) | -- | |

| Naïve to ART at PD, n(%) | 11 (7) | -- | |

| CD4 at PD, median (IQR) | 429 (239–662) | -- | |

| CD8 at PD, median (IQR) | 844 (602–1263) | -- | |

| CD4/CD8 at PD, median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | -- | |

| Suppressed HIV VL at PD, n(%) | |||

| No | 45 (35) | -- | |

| Yes | 84 (65) | -- | |

| Additional cause of IS present, n(%) | 16 (11) | -- | |

| Pre-existing lung disease, n(%) | 21 (14) | -- | |

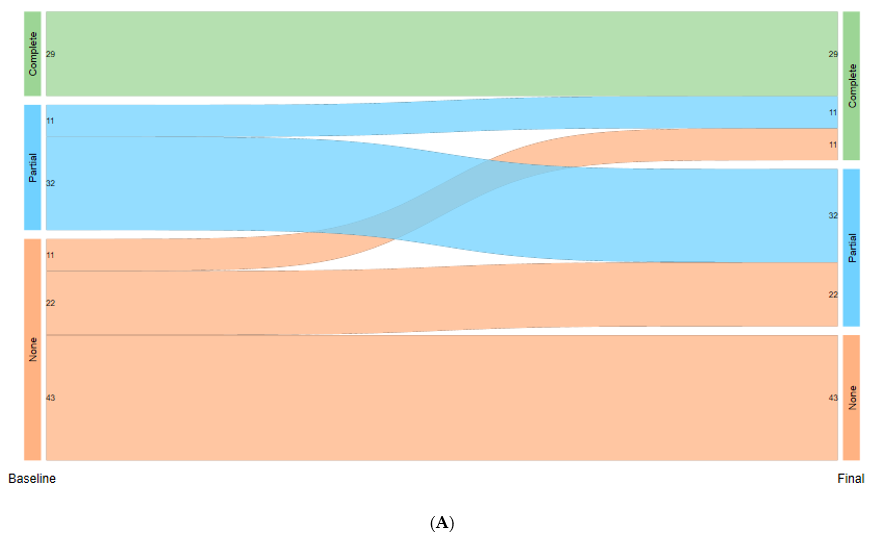

| Vaccination coverage, n(%) | |||

| None | 76 (51) | 6164 (73) | |

| Partial | 43 (29) | 2288 (27) | |

| Complete | 29 (20) | 47 (1) |

| Variable | OR (95% CI)—Simple Model | p-Value | OR (95% CI)—Multiple Model | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birthplace | <0.001 | 0.438 | ||

| Other | 2.06 (1.38–3.06) | 1.19 (0.77–1.82) | ||

| Spain | 1 | 1 | ||

| HIV transmission mode | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 4.58 (3.01–6.95) | 3.43 (2.19–5.36) | ||

| IDU | 1 | 1 | ||

| CD4 nadir 1 | 0.87 (0.82–0.91) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.87–0.98) | 0.005 |

| HIV VL peak 2 | 1.20 (1.11–1.29) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | 0.011 |

| Variable | Severe (N = 26) | Non-Severe (N = 151) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex at birth, n(%) | 0.525 | |||

| Male | 21 (81) | 114 (75) | 1 | |

| Female | 5 (19) | 37 (25) | 0.77 (0.34–1.75) | |

| Age at first episode median (IQR) | 52 (44–58) | 49 (39–58) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.347 |

| Birthplace, n(%) | 0.036 | |||

| Spain | 21 (88) | 87 (63) | 1 | |

| Other | 3 (12) | 51 (37) | 3.50 (1.08–11.29) | |

| HIV transmission mode, n(%) | 0.615 | |||

| Sexual | 14 (56) | 98 (66) | 1 | |

| IDU | 10 (40) | 46 (31) | 1.43 (0.70–2.93) | |

| Vertical | 1 (4) | 5 (3) | 1.33 (0.35–5.04) | |

| CD nadir median (IQR) | 139 (49–272) | 165 (35–301) | 1 (1.00–1.00) | 0.839 |

| CD4 at PD median (IQR) | 337 (175–654) | 325 (160–586) | 1 (1.00–1.00) | 0.708 |

| CD8 at PD median (IQR) | 630 (355–1168) | 822 (480–1273) | 1 (1.00–1.00) | 0.871 |

| CD4/CD8 at PD median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.1–1) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 1.74 (1.36–2.23) | <0.001 |

| Suppressed HIV VL at PD, n(%) | 0.452 | |||

| No | 12 (50) | 58 (42) | 1 | |

| Yes | 12 (50) | 81 (58) | 0.75 (0.36–1.58) | |

| Additional cause of IS, n(%) | 3 (12) | 16 (11) | 1.08 (0.35–3.39) | 0.889 |

| Invasive pneumococcal disease, n(%) | 6 (23) | 23 (15) | 1.53 (0.67–3.50) | 0.313 |

| Hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 11 (7–35) | 5 (1–9) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | <0.001 |

| Vaccination coverage, n(%) | 0.190 | |||

| None | 14 (54) | 71 (47) | 1 | |

| Partial | 11 (42) | 47 (31) | 1.15 | |

| Complete | 1 (4) | 33 (22) | 0.18 (0.02–1.32) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medina, P.; de Lazzari, E.; Espasa, M.; de la Mora, L.; Martínez-Rebollar, M.; González-Cordón, A.; Laguno, M.; Inciarte, A.; Ambrosioni, J.; Calvo, J.; et al. Incidence, Clinical Features, and Vaccination Coverage of Pneumococcal Disease in People Living with HIV: A Retrospective Cohort Study (2015–2024). Vaccines 2025, 13, 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121240

Medina P, de Lazzari E, Espasa M, de la Mora L, Martínez-Rebollar M, González-Cordón A, Laguno M, Inciarte A, Ambrosioni J, Calvo J, et al. Incidence, Clinical Features, and Vaccination Coverage of Pneumococcal Disease in People Living with HIV: A Retrospective Cohort Study (2015–2024). Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121240

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedina, Pere, Elisa de Lazzari, Mateu Espasa, Lorena de la Mora, María Martínez-Rebollar, Ana González-Cordón, Montserrat Laguno, Alexy Inciarte, Juan Ambrosioni, Júlia Calvo, and et al. 2025. "Incidence, Clinical Features, and Vaccination Coverage of Pneumococcal Disease in People Living with HIV: A Retrospective Cohort Study (2015–2024)" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121240

APA StyleMedina, P., de Lazzari, E., Espasa, M., de la Mora, L., Martínez-Rebollar, M., González-Cordón, A., Laguno, M., Inciarte, A., Ambrosioni, J., Calvo, J., Foncillas, A., Sempere, A., Chivite, I., Berrocal, L., Blanco, J. L., Martínez, E., Miró, J. M., Mallolas, J., & Torres, B. (2025). Incidence, Clinical Features, and Vaccination Coverage of Pneumococcal Disease in People Living with HIV: A Retrospective Cohort Study (2015–2024). Vaccines, 13(12), 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121240