Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of a Ready-to-Use Bivalent Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Vaccine in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Herd Selection

2.2. Experimental Design

- Group A (experimental group): 320 piglets intramuscularly vaccinated in the neck at 21 days of age with Porcilis® PCV M Hyo (2 mL) (MSD Animal Health, Rahway, NJ, USA).

- Group B: 309 piglets intramuscularly vaccinated in the neck at 21 days of age with Ingelvac CircoFLEX® (1 mL) (Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) mixed with Ingelvac MycoFLEX® (1 mL) (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany).

- Group C: 309 piglets intramuscularly vaccinated at 21 days of age in each side of the neck with Ingelvac CircoFLEX® (1 mL) (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) and Suvaxyn M Hyo® (Zoetis Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA) (2 mL), followed by a second dose of Suvaxyn M Hyo® (Zoetis Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA) (2 mL) at 42 days of age.

2.3. Efficacy Assessment

2.3.1. Performance

2.3.2. Lung Lesion Evaluation at Slaughter

2.3.3. Sera Collection

- PCV2 viremiaEach serum sample (n = 25/group) was analyzed for the detection of PCV2 and quantification of the viral load using a real-time PCR test (Porcine Circovirus Type 2 Quantitative Kit®, Tianjin Odrei Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjin Shi, China). The lower limit of detection of this kit is 3 target copies/µL. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated by the linear trapezoidal rule as a measure of total shedding over time.

- Serological investigationIn total, 10 serum samples (per group and age category) were investigated for the presence of antibodies against PCV2 (Porcine Circovirus Type 2-d Cap-ELISA Antibody Test Kit, Beijing Jinnuo Baitai Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Kino, Republic of Korea), M. hyopneumoniae (IDEXX Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Antibody Test Kit, Beijing IDEXX Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), and A. pleuropneumoniae (IDEXX Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae Antibody Test Kit, Beijing IDEXX Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Results were expressed as negative, positive, or doubtful according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

2.3.4. Laryngeal Swab Collection

2.4. Safety Assessment

2.5. Economic Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Statement for Experimental Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Efficacy Assessment

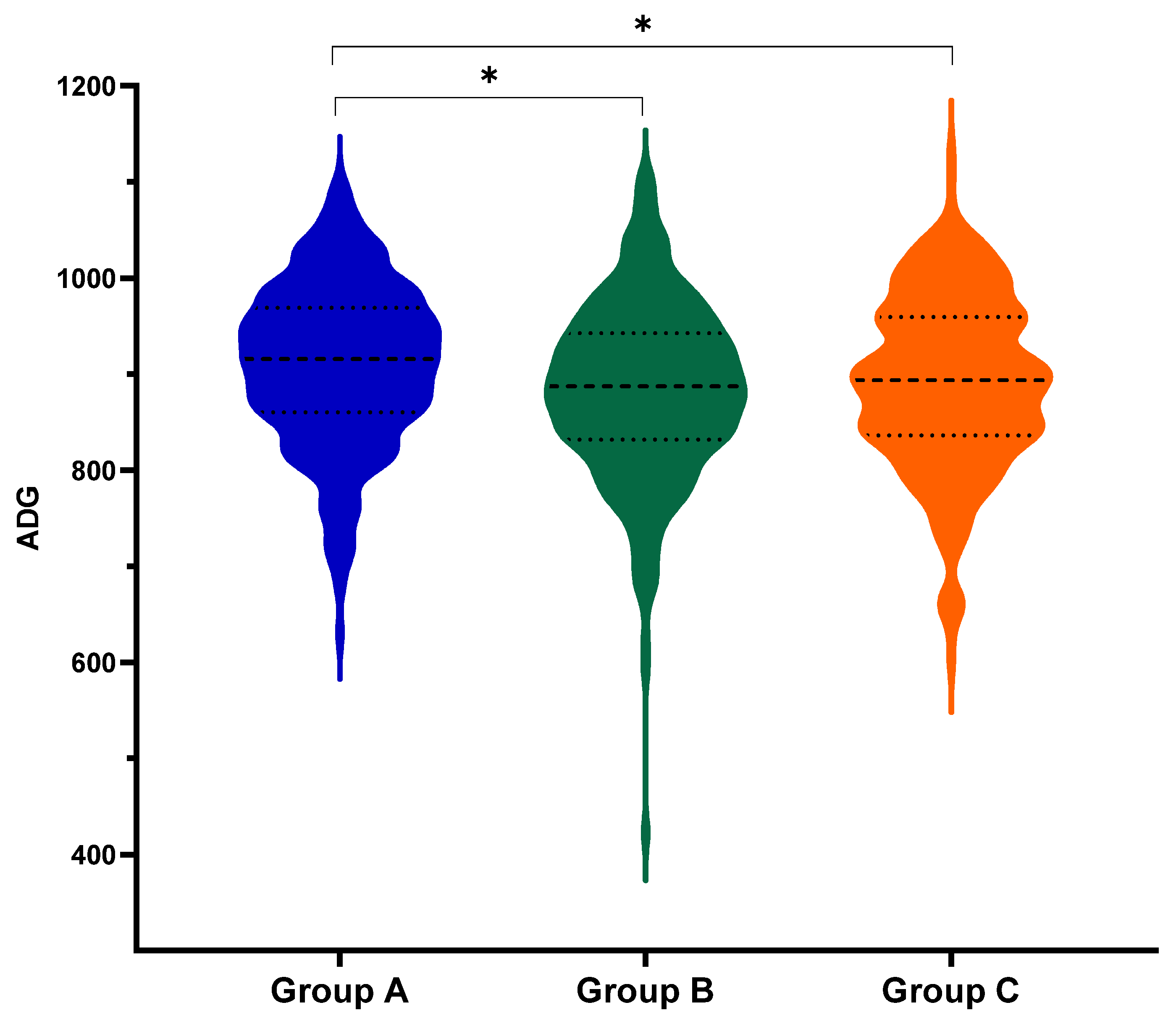

3.1.1. Performance

3.1.2. Lung Lesions at Slaughter

3.1.3. Sera Sampling

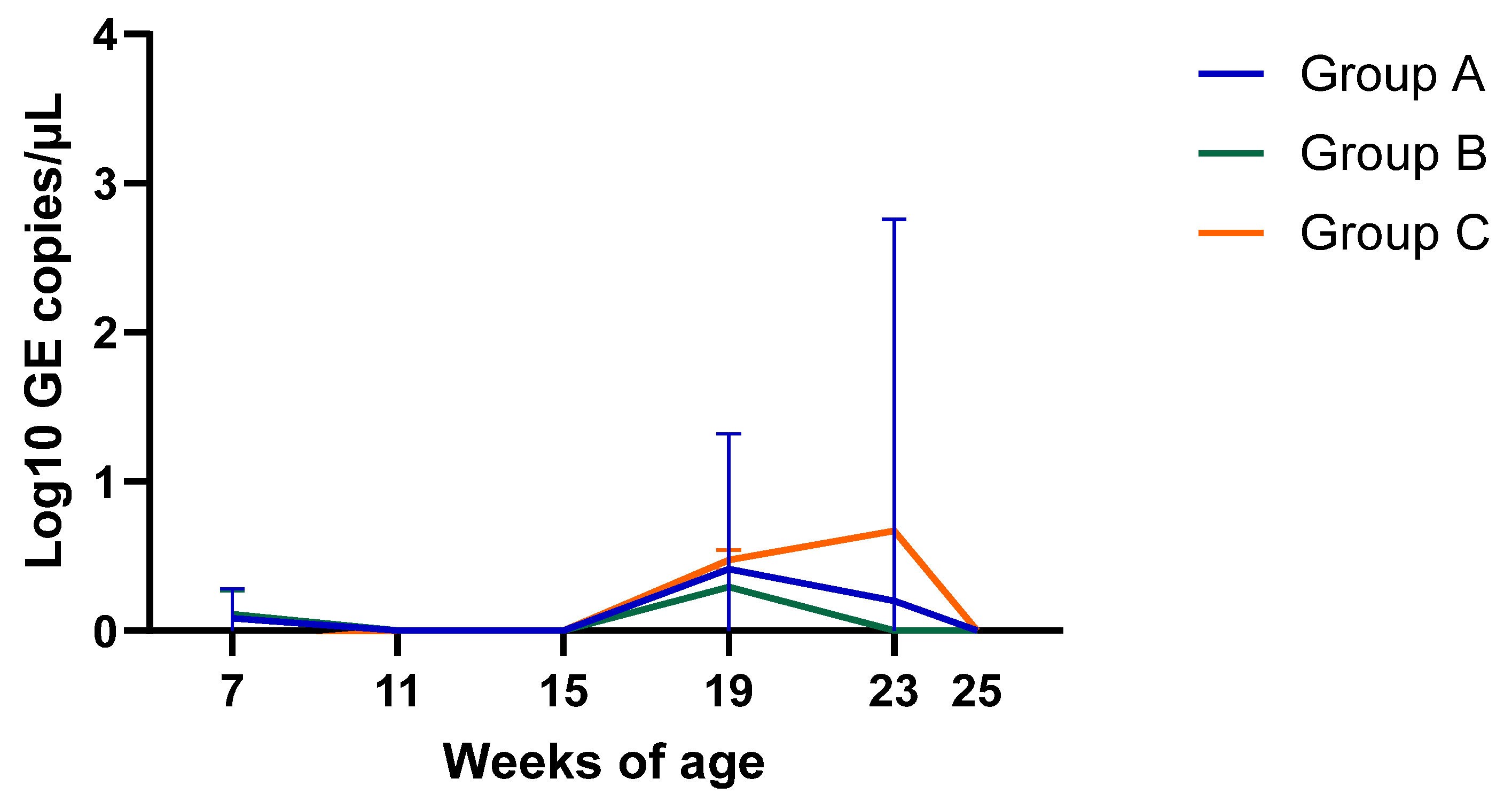

- PCV2 viremiaPCV2 viremia remained either undetectable or at very low levels during the whole study in all three groups. Time course of PCV2 viremia in is plotted in Figure 2; the average Log10 GE copies/µL shown is limited to the few viremic pigs. Peak of viremia occurred between 19 and 23 weeks of age, and those viremic pigs had very low viral load (<0.7 Log10 GE copies/µL). Due to this low viremia, sequencing was unsuccessful, and the genotype was not determined. The AUC of all sampled pigs was 2.54, 0.71, and 1.74 (p > 0.05) for Group A, B, and C, respectively.

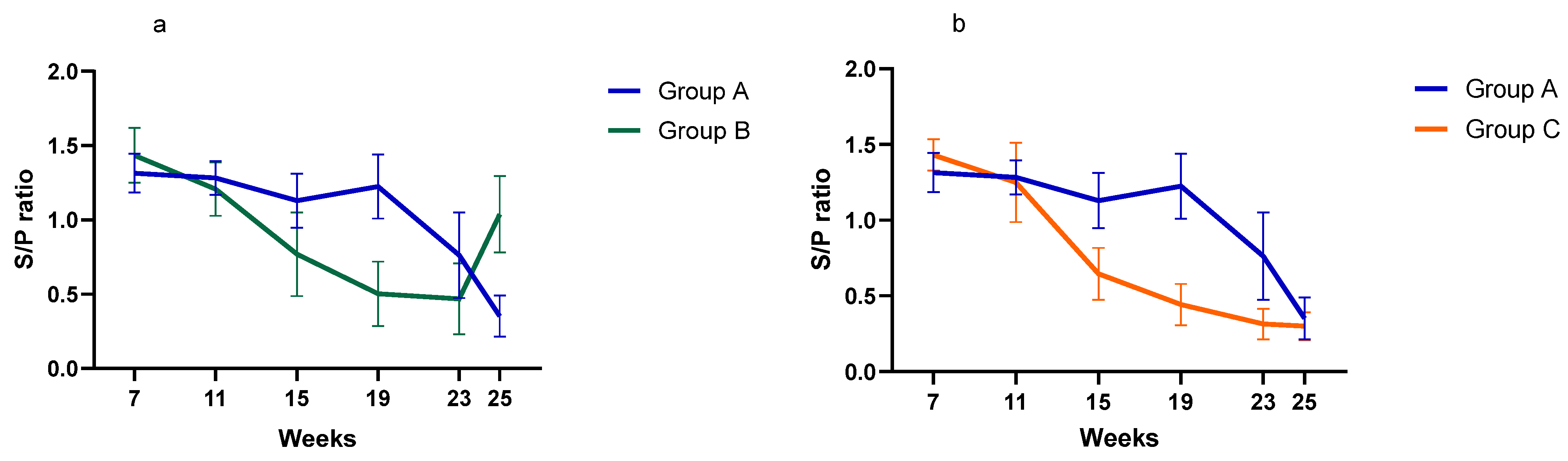

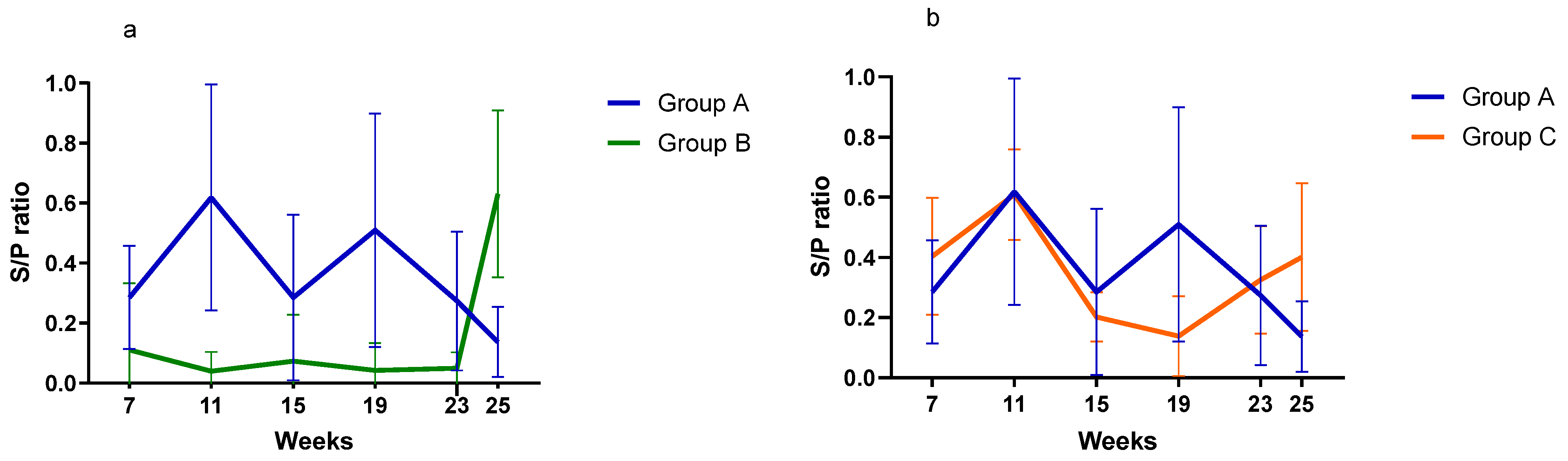

- Serological investigationResults from the serology investigation are displayed on Figure 3 and Figure 4, and Table 3. Overall, PCV2 antibodies were present in all three groups at 7 weeks of age. In Group A, average S/P ratio remained stable up to 19 weeks and then declined. For Groups B and C, the decline was much more pronounced from 11 weeks onward. Pigs from Group B seroconverted at 25 weeks (90% seropositive).Regarding M. hyopneumoniae, the serology investigation revealed different infection dynamics among groups (Figure 4). In Group A, S/P ratio values and seroprevalence (60%) peak at 11 weeks, and then gradually declined from 19 weeks of age onward. For Group B, most pigs remained seronegative during the study, except for a large seroconversion (80%) at 25 weeks. All pigs from Group C had seroconverted (100%) by 11 weeks, then S/P values and seroprevalence declined to a minimum, to slightly increase again after 19 weeks. For A. pleuropneumoniae, no differences were observed among groups (Table 3).

3.1.4. Laryngeal Swab Collection

3.2. Safety Assessment

3.3. Economic Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RTU | Ready-To-Use |

| PCV2 | Porcine Circovirus Type 2 |

| M. hyopneumoniae | Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae |

| ADG | Average Daily Gain |

| PCVD | Porcine Circovirus Disease |

| PRRSV | Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| LLS | Lung Lesion Score |

| SPES | Slaughterhouse Pleurisy Evaluation System method |

| Real-time PCR | Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| RMB | Renminbi |

| AN(C)OVA | Analysis of Covariance |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| GE | Genomic Equivalent |

| A. pleuropneumoniae | Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae |

| Δ | Difference |

| VLPs | Virus-Like Particles |

References

- Saade, G.; Deblanc, C.; Bougon, J.; Marois-Crehan, C.; Fablet, C.; Auray, G.; Belloc, C.; Leblanc-Maridor, M.; Gagnon, C.A.; Zhu, J.; et al. Coinfections and their molecular consequences in the porcine respiratory tract. Vet. Res. 2020, 51, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalés, J.; Sibila, M. Revisiting Porcine Circovirus Disease diagnostic criteria in the current Porcine Circovirus 2 epidemiological context. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segalés, J. Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) infections: Clinical signs, pathology and laboratory diagnosis. Virus Res. 2012, 164, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segalés, J. Best practice and future challenges for vaccination against Porcine Circovirus type 2. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madec, F.; Eveno, E.; Morvan, P.; Hamon, L.; Blanchard, P.; Cariolet, R.; Amenna, N.; Morvan, H.; Truong, C.; Mahé, D.; et al. Post-weaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS) in pigs in France: Clinical observations from follow-up studies on affected farms. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2000, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, D.; Segales, J.; Meyns, T.; Sibila, M.; Pieters, M.; Haesebrouck, F. Control of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infections in pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 126, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, M.; Maes, D. Mycoplasmosis. In Diseases of Swine, 11th ed.; Zimmerman, J.J., Karriker, L.A., Ramirez, A., Schwartz, K.J., Stevenson, G.W., Zhang, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 863–883. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, D.; Sibila, M.; Kuhnert, P.; Segalés, J.; Haesebrouck, F.; Pieters, M. Update on Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae infections in pigs: Knowledge gaps for improved disease control. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opriessnig, T.; Thacker, E.; Yu, S.; Fenaux, M.; Meng, X.; Halbur, P. Experimental reproduction of postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in pigs by dual infection with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and Porcine circovirus type 2. Vet. Pathol. 2004, 41, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, H.; Zhang, G.; Wu, F.; Zhang, C. Detection of serum antibody against postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in pigs. Chin. J. Vet. Sci. Technol. 2000, 30, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCI Consulting. 2023 China Swine Health Market Study. In SCI Consulting Report; SCI Consulting: Fairfield, CA, USA, August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, Q.L.; Nie, L.B.; Wang, Q.; Ge, G.Y.; Li, D.L.; Ma, B.Y.; Sheng, C.Y.; Su, N.; Zong, Y.; et al. Prevalence of Porcine Circovirus 2 throughout China in 2015-2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Hao, F.; Xu, L.; Guo, K. Genetic diversity and prevalence of Porcine Circovirus Type 2 in China during 2000-2019. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 788172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Bian, L.; Tian, X.; Hu, Z.; Wu, W.; Sun, L.; Yuan, G.; Li, S.; Yue, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Infection characteristics of Porcine Circovirus type 2 in different herds from intensive farms in China, 2022. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1187753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.L.; Chen, S.N.; Xu, Z.H.; Tang, M.H.; Wang, F.G.; Li, X.J.; Sun, B.B.; Deng, S.F.; Hu, J.; Lv, D.H.; et al. Porcine circovirus type 2 in China: An update on and insights to its prevalence and control. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Hou, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, D.; Cui, Y.; Feng, X.; Liu, J. Porcine Circovirus Type 2 vaccines: Commercial application and research advances. Viruses 2022, 14, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, R. Genotype diversity of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in Chinese swine herds based on multilocus sequence typing. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liang, L.; Qin, Y.; Cheng, K.; Chen, Z.; Lu, B.; Duan, Q.; Peng, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. Epidemiological investigation of porcine Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in pig herds in Guangxi, China (2022–2023) and genetic diversity analysis based on multilocus sequence typing. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Bosch, J.; Martínez-Avilés, M.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M. The evolution of African Swine Fever in China: A global threat? Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 828498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Yu, W.; Clora, F. Boom and bust in China’s pig sector during 2018–2021: Recent recovery from the ASF shocks and longer-term sustainability considerations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvliet, M.; Holtslag, H.; Nell, T.; Segers, R.; Fachinger, V. Efficacy and safety of a combined Porcine Circovirus and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine in finishing pigs. Trials Vaccinol. 2015, 4, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagot, E.; Rigaut, M.; Roudaut, D.; Panzavolta, L.; Jolie, R.; Duivon, D. Field efficacy of Porcilis® PCV M Hyo versus a licensed commercially available vaccine and placebo in the prevention of PRDC in pigs on a French farm: A randomized controlled trial. Porc. Health Manag. 2017, 3, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzika, E.D.; Tassis, P.D.; Koulialis, D.; Papatsiros, V.G.; Nell, T.; Brellou, G.; Tsakmakidis, I. Field efficacy study of a novel ready-to-use vaccine against Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and Porcine Circovirus Type 2 in a Greek farm. Porc. Health Manag. 2015, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaalberg, L.; Geurts, V.; Jolie, R. A field efficacy and safety trial in the Netherlands in pigs vaccinated at 3 weeks of age with a ready-to-use Porcine Circovirus type 2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae combined vaccine. Porc. Health Manag. 2017, 3, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Lorenzo, G.; Prieto, A.; López-Novo, C.; Díaz, P.; López, C.M.; Morrondo, P.; Fernández, G.; Díaz-Cao, J.M. Efficacy of two commercial Ready-To-Use PCV2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccines under field conditions. Animals 2021, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, D.; Sibila, M.; Pieters, M.; Haesebrouck, F.; Segalés, J.; de Oliveira, L.G. Review on the methodology to assess respiratory tract lesions in pigs and their production impact. Vet. Res. 2023, 54, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madec, F.; Kobisch, M. Bilan lesionnel des poumons de porcs charcutiers à l’abattoir. JRP 1982, 14, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Merialdi, G.; Dottori, M.; Bonilauri, P.; Luppi, A.; Gozio, S.; Pozzi, P.; Spaggiari, B.; Martelli, P. Survey of pleuritis and pulmonary lesions in pigs at abattoir with a focus on the extent of the condition and herd risk factors. Vet. J. 2012, 193, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pig Price in China—MOA—Live. Available online: https://www.3tres3.com/en-af/markets_and_prices/china_106/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Holtkamp, D. Key Performance Indicators in Pork Production: An International Comparison. In Proceedings of the 12th Leman China Swine Conference, Xi’an, China, 20 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, G.M.; McNeilly, F.; Kennedy, S.; Daft, B.; Clarke, E.G.; Ellis, J.A.; Haines, D.M.; Meehan, B.M.; Adair, B.M. Isolation of porcine circovirus-like viruses from pigs with a wasting disease in the USA and Europe. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1998, 10, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Hassard, L.; Clark, E.; Harding, J.; Allan, G.; Willson, P.; Strokappe, J.; Martin, K.; McNeilly, F.; Meehan, B.; et al. Isolation of circovirus from lesions of pigs with postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome. Can. Vet. J. 1998, 39, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- National Veterinary Drug Basic Database. Available online: http://vdts.ivdc.org.cn:8099/cx/# (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Chae, C. Commercial porcine circovirus type 2 vaccines: Efficacy and clinical application. Vet. J. 2012, 194, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.R.; Ramamoorthy, S.; Madson, D.M.; Meng, X.J.; Halbur, P.G.; Opriessnig, T. Shedding and infection dynamics of Porcine Circovirus type 2 (PCV2) after experimental infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 149, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileri, E.; Mateu, E. Review on the transmission porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus between pigs and farms and impact on vaccination. Vet. Res. 2016, 47, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madapong, A.; Saeng-Chuto, K.; Tantituvanont, A.; Nilubol, D. Safety of PRRSV-2 MLV vaccines administrated via the intramuscular or intradermal route and evaluation of PRRSV transmission upon needle-free and needle delivery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Lin, H.; Suntisukwattana, R.; Watcharavongtip, P.; Jermsutjarit, P.; Tantituvanont, A.; Nilubol, D. Intradermal needlefree injection prevents African Swine Fever transmission, while intramuscular needle injection does not. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hsueh, F.C.; Chien, C.Y.; Chang, S.W.; Lian, B.R.; Lin, H.Y.; Ellerma, L.; Chiou, M.T.; Lin, C.N. Field evaluation of a Ready-to-Use Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine in naturally infected farms in Taiwan. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo Sacristan, R. Treatment and Control of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Infections. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 25 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic, S.; Eamens, G.; Romalis, L.; Nicholls, P.; Taylor, V.; Chin, J. Serum and mucosal antibody responses and protection in pigs vaccinated against Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae with vaccines containing a denatured membrane antigen pool and adjuvant. Aust. Vet. J. 1997, 75, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thacker, E.; Thacker, B.; Boettcher, T.; Jayappa, H. Comparison of antibody production, lymphocyte stimulation, and protection induced by four commercial Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae bacterins. J. Swine Health Prod. 1998, 6, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Fan, F.; Chen, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Li, R.; Dong, W.; Ge, M. Evaluation of PCV2 vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy using ELISpot to detect virus-specific memory B cells. Porc. Health Manag. 2025, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileri, E.; Cortey, M.; Rodríguez, F.; Sibila, M.; Fraile, L.; Segalés, J. Comparison of the immunoperoxidase monolayer assay and three commercial ELISAs for detection of antibodies against Porcine Circovirus type 2. Vet. J. 2014, 201, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderohe, C.E.; Brizgys, L.A.; Richert, J.A.; Radcliffe, J.S. Swine production: How sustainable is sustainability? Anim. Front. 2022, 12, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, J.L. The impact of controlling diseases of significant global importance on greenhouse gas emissions from livestock production. One Health Outlook 2023, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group A | Group B | Group C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live weight | n = 320 | n = 309 | n = 309 |

| at day 0 (mean ± SD) | 5.08 ± 0.60 | 5.07 ± 0.60 | 5.09 ± 0.60 |

| at day 100 (mean ± SD) | 85.73 ± 9.41 | 80.59 ± 9.55 | 80.27 ± 8.64 |

| prior to slaughter (mean ± SEM) | 145.6 ± 0.8 A | 141.6 ± 0.8 B | 141.4 ± 0.8 B |

| Coefficient of variation Live weight prior slaughter | 8.71% | 9.45% | 9.82% |

| ADG | |||

| day 0–100 (mean ± SEM) | 796.6 ± 5.3 A | 742.9 ± 5.4 B | 752.3 ± 5.4 B |

| day 100—slaughter (mean ± SEM) | 1131.3 ± 17.5 A | 1160.0 ± 18.1 A | 1156.1 ± 18.4 A |

| day 0—slaughter (mean ± SEM) | 911.1 ± 5.0 A | 885.1 ± 5.0 B | 890.7 ± 5.0 B |

| Days to slaughter | 154.2 | 154.2 | 153.0 |

| Mortality % | 5.3 A | 4.5 A | 5.8 A |

| % pigs under slaughter weight | 0.63 A | 0.65 A | 0.00 A |

| Group A (n = 63) | Group B (n = 67) | Group C (n = 65) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of Pneumonia | 36.5% A | 92.5% B | 58.5% B |

| Lung Lesion Score (LLS) | 0.92 ± 1.65 A | 5.93 ± 4.08 B | 1.43 ± 2.06 A |

| # lungs with | |||

| Score 0 | 40 | 5 | 27 |

| Score 1–4 | 20 | 31 | 34 |

| Score 5–9 | 3 | 19 | 4 |

| Score 10–14 | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Score 15–19 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Score 20–24 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Score 25–28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Group | 7 Week | 11 Week | 15 Week | 19 Week | 23 Week | 25 Week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCV2 | A | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 80% | 40% |

| B | 100% | 100% | 90% | 70% | 50% | 90% | |

| C | 100% | 100% | 90% | 70% | 20% | 20% | |

| M. hyopneumoniae * | A | 40% | 60% | 50% | 60% | 30% | 20% |

| B | 10% | 0% | 10% | 10% | 0% | 80% | |

| C | 70% | 100% | 20% | 20% | 50% | 50% | |

| A. pleuropneumoniae * | A | 80% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 10% |

| B | 70% | 60% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| C | 80% | 70% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Systemic Reactions | Group A | Group B | Group C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe | 0/320 | 0/309 | 0/309 |

| Moderate | 0/320 | 0/309 | 0/309 |

| Mild | 2/320 | 2/309 | 0/309 |

| Local reactions | 0/320 | 0/309 | 0/309 |

| Economic Parameters | Group A | Group B | Δ (A–B) | Group C | Δ (A-C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Final Live Weight (kg) | 145.55 | 141.52 | 4.03 | 141.45 | 4.10 |

| Prevalence of healthy lungs (%) | 64.50 | 7.50 | 57.00 | 41.50 | 23.00 |

| # needles used/vaccinated pig | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | −2 |

| Mortality % | 5.30 | 4.50 | 0.80 | 5.80 | −0.50 |

| Revenue (RMB) | |||||

| Per Pig/sold 1 | 2196.35 | 215.54 | 60.81 | 2134.48 | 61.87 |

| Per healthy lung sold 2 | 1.29 | 0.15 | 1.14 | 0.83 | 0.46 |

| Costs (RMB) | |||||

| Needle costs/pig sold 3 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 0.01 | 3.19 | −2.13 |

| Cost of Mortality 4 | 51.30 | 43.56 | 7.74 | 56.14 | −4.84 |

| Net profit (RMB) | |||||

| Per pig sold | 2145.28 | 2091.08 | 54.20 | 2075.98 | 69.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, H.; Mo, Y.; Luo, W.; Xie, X.; Li, Z.; Tang, S.; Liu, X.; Cao, Q.; Lin, H.; Gao, D.; et al. Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of a Ready-to-Use Bivalent Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Vaccine in China. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121203

Yan H, Mo Y, Luo W, Xie X, Li Z, Tang S, Liu X, Cao Q, Lin H, Gao D, et al. Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of a Ready-to-Use Bivalent Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Vaccine in China. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121203

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Huimeng, Yupeng Mo, Wanfa Luo, Xiong Xie, Zeyu Li, Shuming Tang, Xiaoxin Liu, Qi Cao, Hongyao Lin, Di Gao, and et al. 2025. "Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of a Ready-to-Use Bivalent Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Vaccine in China" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121203

APA StyleYan, H., Mo, Y., Luo, W., Xie, X., Li, Z., Tang, S., Liu, X., Cao, Q., Lin, H., Gao, D., Del Pozo Sacristan, R., & Wang, X. (2025). Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of a Ready-to-Use Bivalent Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae Vaccine in China. Vaccines, 13(12), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121203