Vaccine Attitudes Among Adults in a Southern European Region: Survey from Pre- to Post-COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Survey Procedure

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studied Population

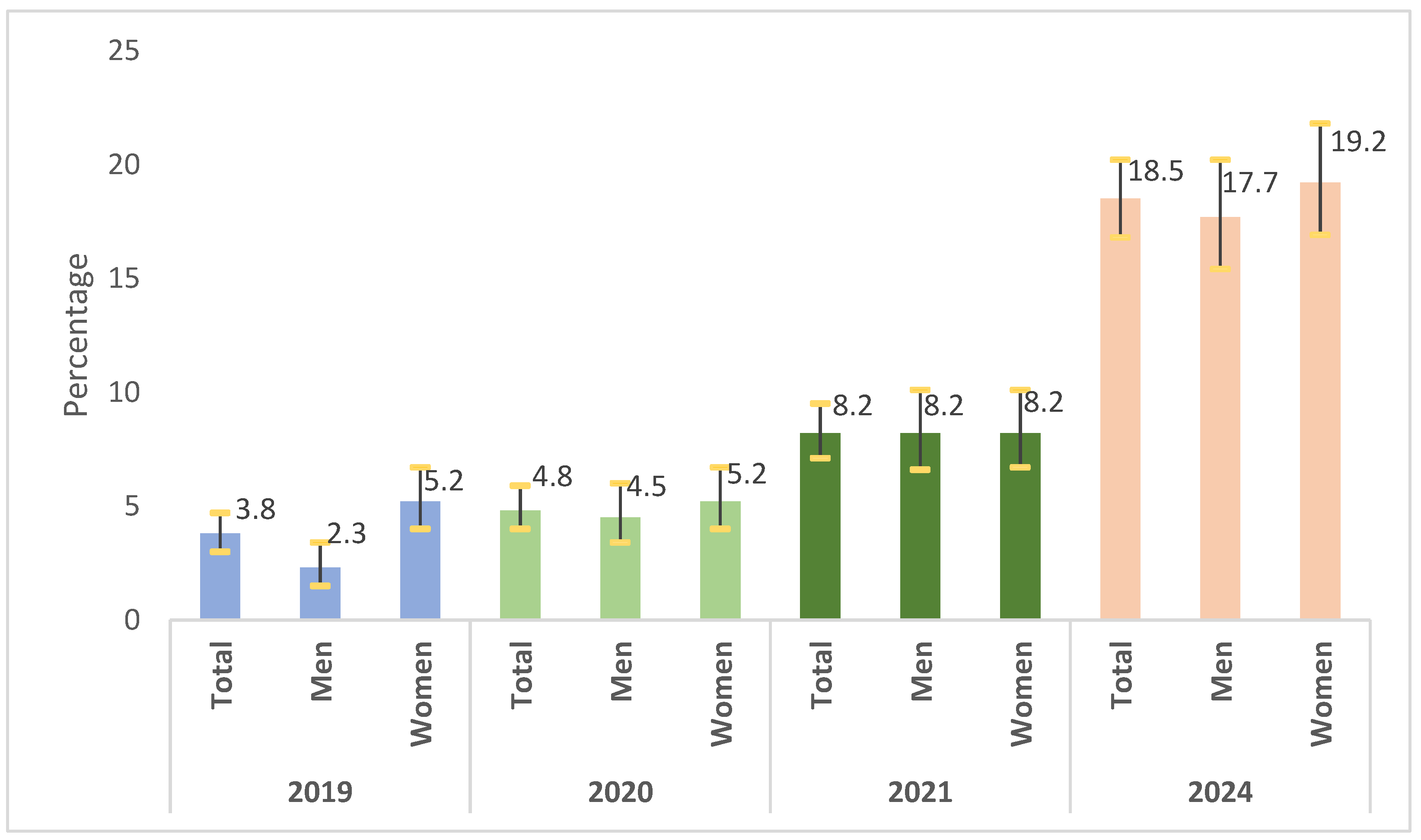

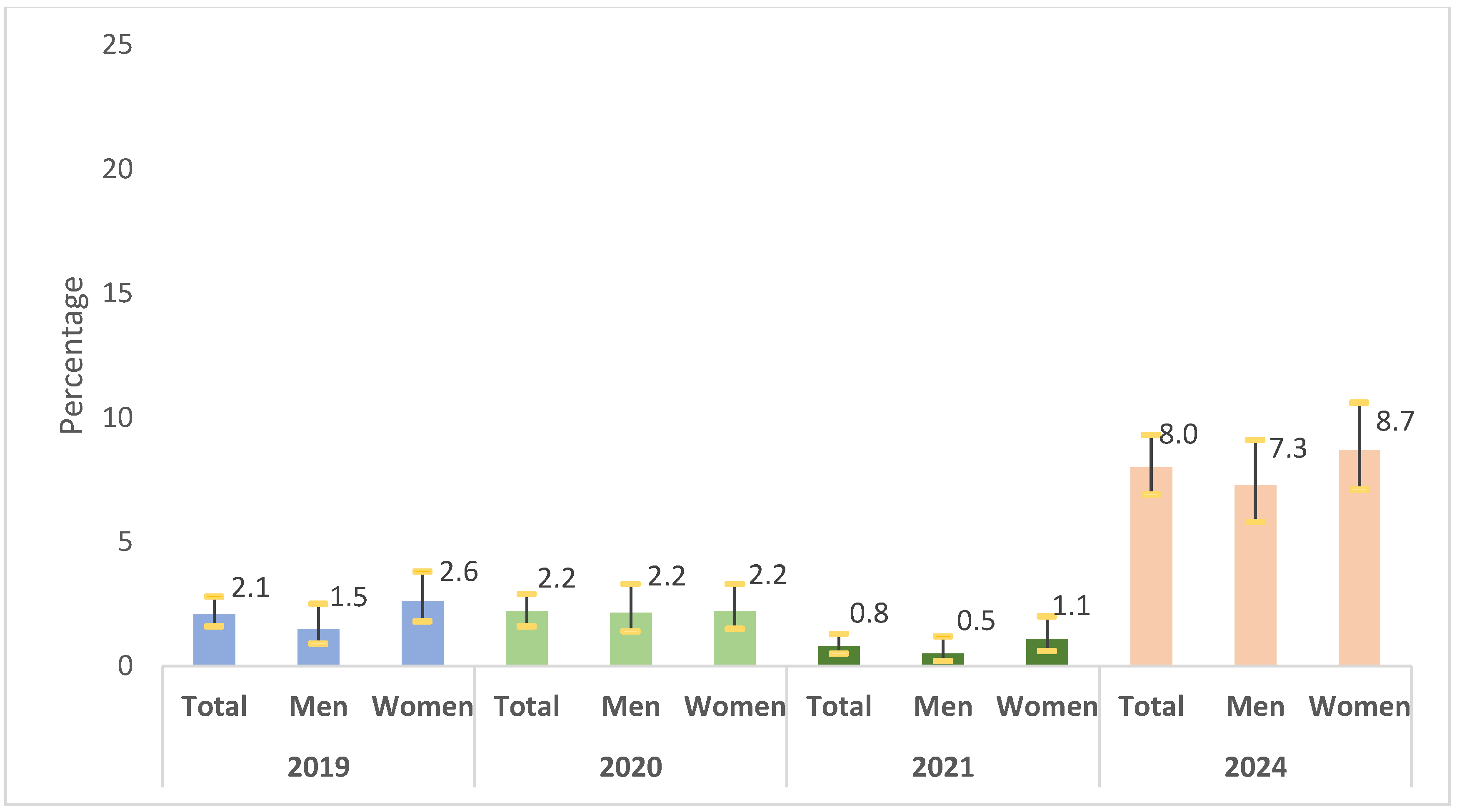

3.2. Prevalence of Vaccine Hesitancy and Refusal

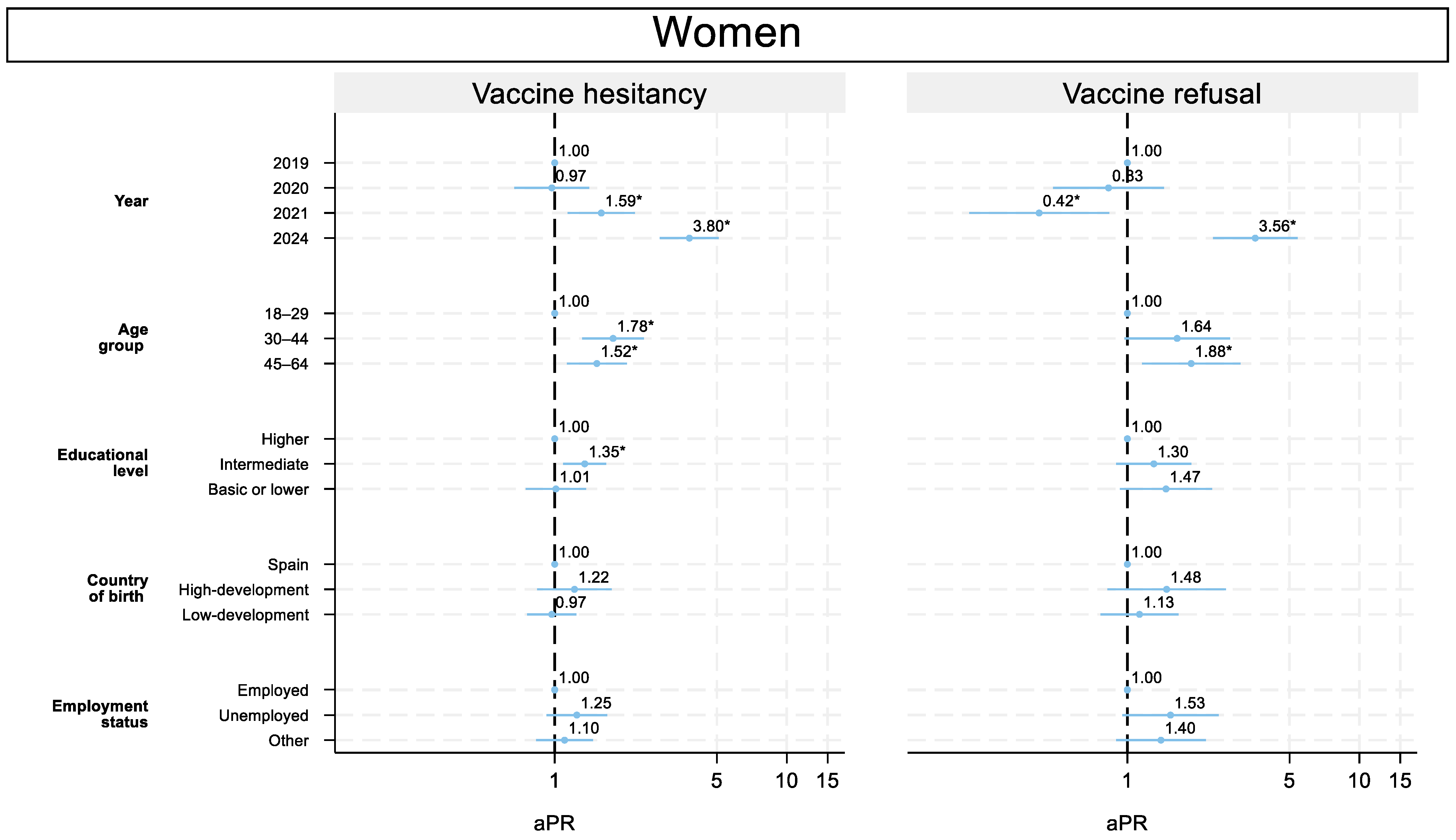

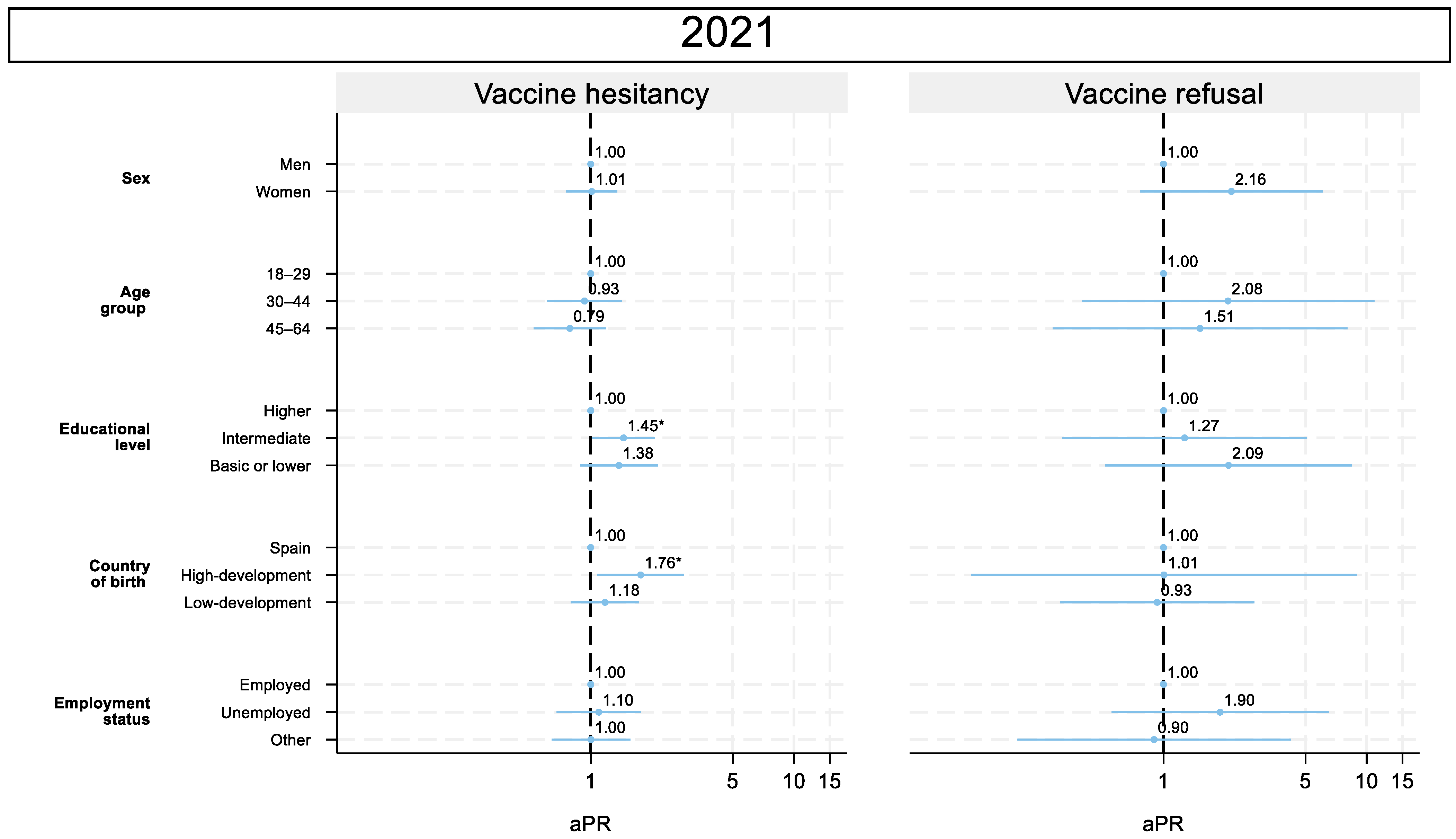

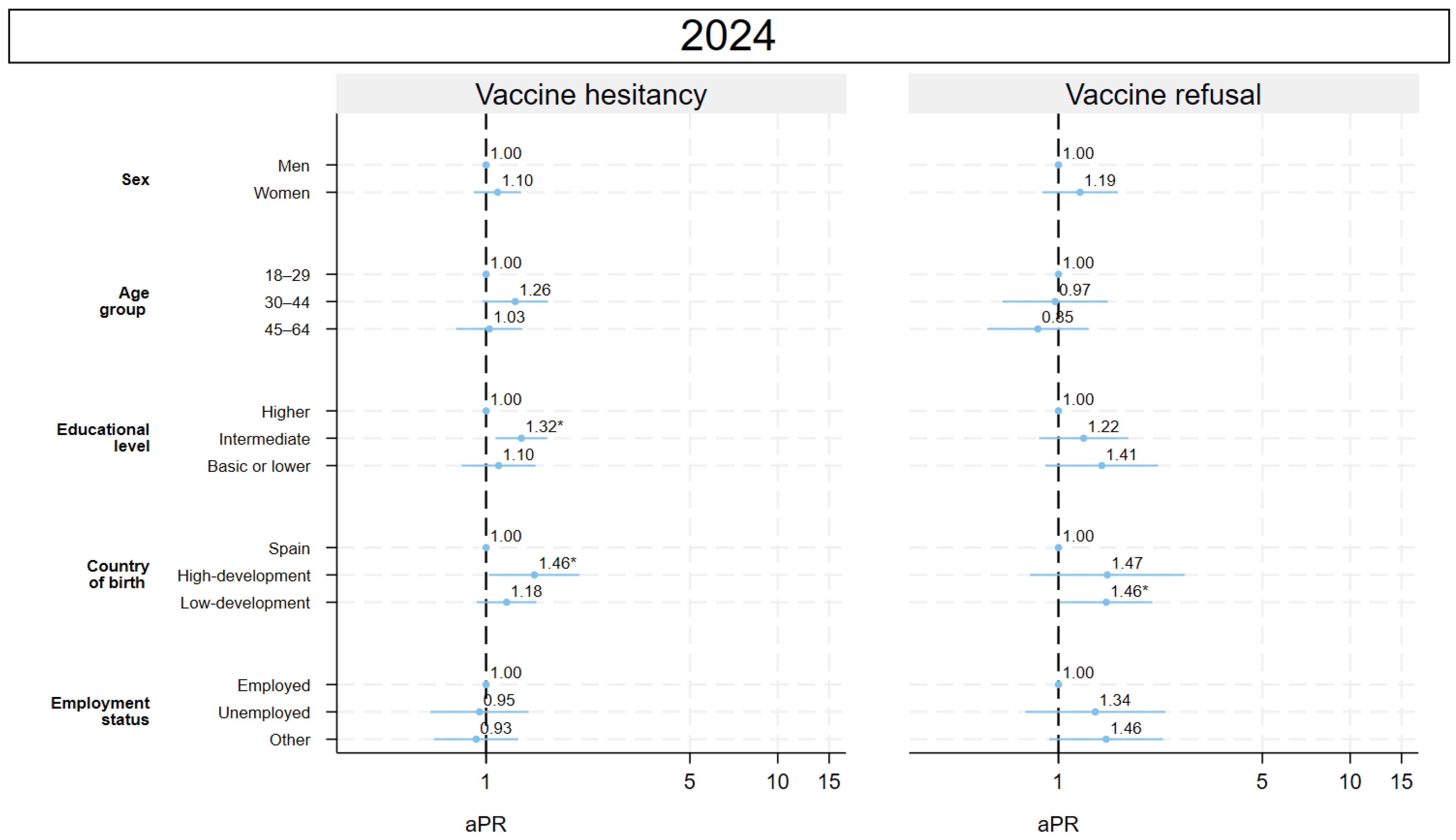

3.3. Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

3.4. Sex Differences

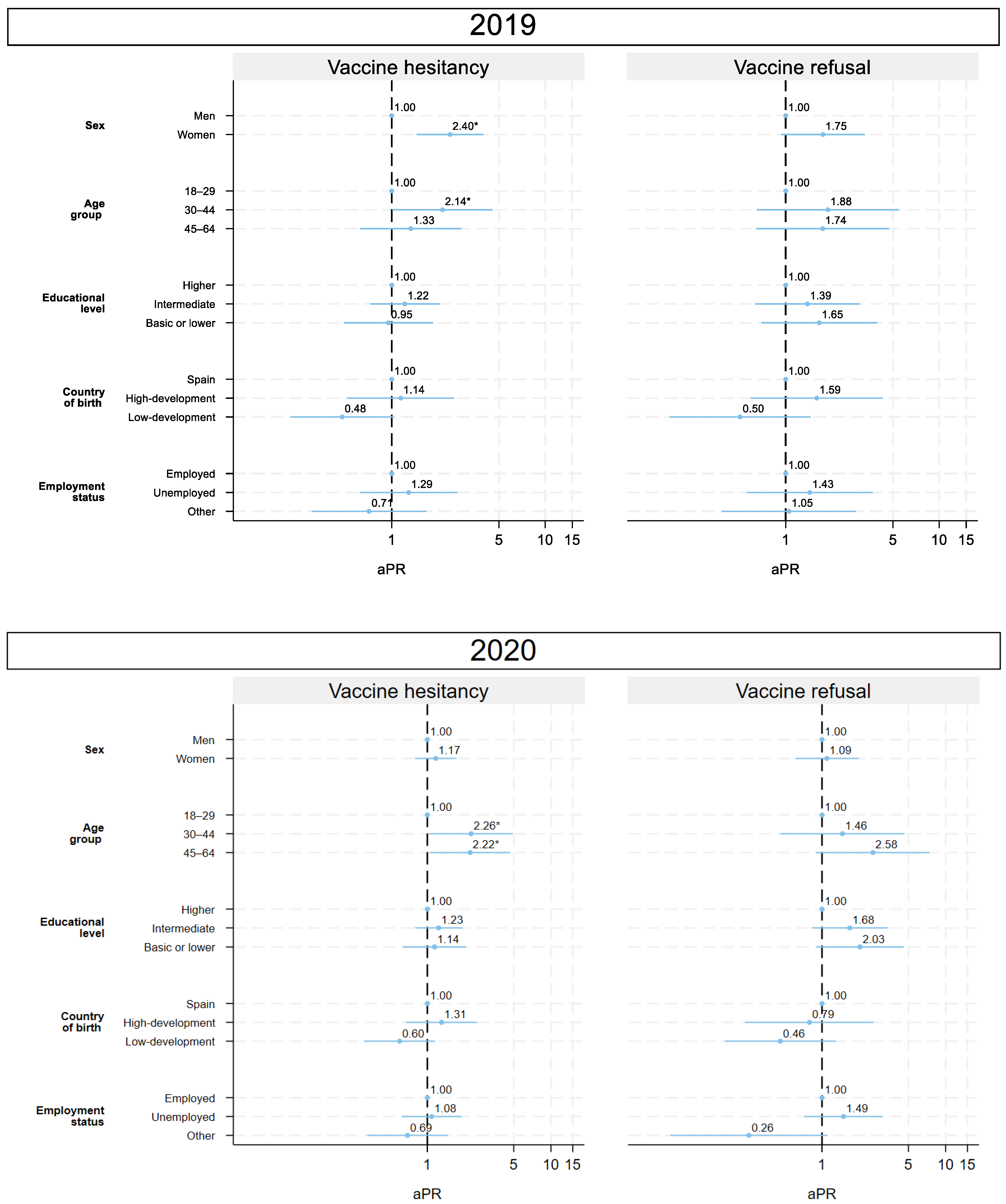

3.5. Evolution of the Association with the Socioeconomic Variables (2019–2024)

3.5.1. 2019: Pre-COVID-19

3.5.2. 2020: Onset of COVID-19

3.5.3. 2021: COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign

3.5.4. 2024: Post-COVID-19

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aPR | Adjusted Prevalence Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CM | Community of Madrid |

| CATI | Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| HDI | Human Development Index |

| NCD | Noncommunicable Disease |

| SIVFRENT-A | Sistema de Vigilancia de Factores de Riesgo Asociados a Enfermedades No Transmisibles-población Adulta |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Vaccine Hesitancy. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/immunization/demand/summary-of-sage-vaccinehesitancy-en.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Fenta, E.T.; Tiruneh, M.G.; Delie, A.M.; Kidie, A.A.; Ayal, B.G.; Limenh, L.W.; Astatkie, B.G.; Workie, N.K.; Yigzaw, Z.A.; Bogale, E.K.; et al. Health literacy and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance worldwide: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2023, 11, 20503121231197869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, H.; Tian, L.; Pang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Huang, T.; Fan, J.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H. COVID-19 vaccine development: Mile-stones, lessons and prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.K.; Sun, J.; Jang, S.; Connelly, S. Misinformation of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, M.R.; Alzubaidi, M.S.; Shah, U.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Shah, Z. A Scoping Review to Find Out Worldwide COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Underlying Determinants. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcec, R.; Majta, M.; Likic, R. Will vaccination refusal prolong the war on SARS-CoV-2? Postgrad. Med. J. 2021, 97, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.M.; Corrin, T.; Pussegoda, K.; Baumeister, A.; Waddell, L.A. Evidence brief on facilitators, barriers and hesitancy of COVID-19 booster doses in Canada. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2024, 50, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Eckersberger, E.; Smith, D.M.D.; Paterson, P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of Spain. La Campaña de Vacunación Contra el COVID-19 Llega a Su Segundo Mes en España Con un Total de 1.243.783 Personas Inmunizadas. Available online: https://vsf-iwsold-pro-portal.sanidad.gob.es/fr/gabinete/notasPrensa.do?id=5245 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Población por Sexo Municipios y País de Nacimiento (33845). INE. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=33845#_tabs-tabla (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Caballero, P.; Astray, J.; Domínguez, Á.; Godoy, P.; Barrabeig, I.; Castilla, J.; Tuells, J. Validación del cuestionario sobre vacunas y reticencia a vacunarse en la Sociedad Española de Epidemiología. Gac. Sanit. 2023, 37, 102329. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Salvany, A.; Bacigalupe, A.; Carrasco, J.M.; Espelt, A.; Ferrando, J.; Borrell, C. Propuestas de clase social neoweberiana y neomarxista a partir de la Clasificación Nacional de Ocupaciones 2011. Gac. Sanit. 2013, 27, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Cai, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W.; Ha, Y.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Chinese residents: A national cross-sectional survey in the community setting. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2481003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguet-Feixa, A.; Artigues-Barberà, E.; Sol, J.; Gomez-Arbones, X.; Godoy, P.; Bravo, M.O. Vaccine refusal and hesitancy in Spain: An online cross-sectional questionnaire. BMC Prim. Care 2025, 26, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, J.I.; Sternberg, H.; Prince, H.; Fasolo, B.; Galizzi, M.M.; Büthe, T.; Veltri, G.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in eight European countries: Prevalence, determinants, and heterogeneity. Sci Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Araújo, J.S.T.; Delpino, F.M.; Andrade-Gonçalves, R.L.d.P.; Aragão, F.B.A.; Ferezin, L.P.; Santos, D.A.; Neto, N.C.D.; Nascimento, M.C.D.; Moreira, S.P.T.; Ribeiro, G.F.; et al. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachtigall, I.; Bonsignore, M.; Hohenstein, S.; Bollmann, A.; Günther, R.; Kodde, C.; Englisch, M.; Ahmad-Nejad, P.; Schröder, A.; Glenz, C.; et al. Effect of gender, age and vaccine on reactogenicity and incapacity to work after COVID-19 vaccination: A survey among health care workers. BMC Infect Dis. 2022, 22, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | 2019 N (%) | 2020 N (%) | 2021 N (%) | 2024 N (%) | Total N (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% by row) | 1997 (25.0) | 2002 (25.1) | 1990 (24.9) | 1989 (24.9) | 7978 (100.0) | |

| Mean age (years) (DS) | 41.94 (12.50) | 41.99 (12.51) | 42.05 (12.83) | 41.89 (12.38) | 41.97 (12.55) | 0.983 |

| Age group | 0.384 | |||||

| 18–29 years | 401 (20.1) | 399 (19.9) | 427 (21.5) | 428 (21.5) | 1655 (20.7) | |

| 30–44 years | 741 (37.1) | 743 (37.1) | 684 (34.4) | 691 (34.7) | 2859 (35.8) | |

| 45–64 years | 855 (42.8) | 860 (43.0) | 879 (44.2) | 870 (43.7) | 3464 (43.4) | |

| Sex | 0.914 | |||||

| Men | 974 (48.8) | 975 (48.7) | 978 (49.1) | 989 (49.7) | 3916 (49.1) | |

| Women | 1023 (51.2) | 1027 (51.3) | 1012 (50.9) | 1000 (50.3) | 4062 (50.9) | |

| Country of birth | 0.027 | |||||

| Spain | 1533 (76.8) | 1552 (77.5) | 1569 (78.8) | 1534 (77.1) | 6188 (77.6) | |

| High-development country | 138 (6.9) | 137 (6.8) | 108 (5.4) | 99 (5.0) | 482 (6.0) | |

| Low-development country | 326 (16.3) | 313 (15.6) | 313 (15.7) | 356 (17.9) | 1308 (16.4) | |

| Geographic area | 0.262 | |||||

| City of Madrid | 970 (48.6) | 972 (48.6) | 975 (49.0) | 971 (48.8) | 3888 (48.7) | |

| Metropolitan area | 824 (10.2) | 826(41.3) | 846(42.5) | 852(42.8) | 3348(42.0) | |

| Rest | 203 (10.2) | 204 (10.2) | 169 (8.5) | 166 (8.3) | 742 (9.3) | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | |||||

| Higher | 769 (38.5) | 809 (40.5) | 798 (40.1) | 962 (48.5) | 3338 (41.9) | |

| Intermediate | 776 (38.9) | 815 (40.8) | 809 (40.7) | 729 (36.8) | 3129 (39.3) | |

| Basic or lower | 452 (22.6) | 376 (18.8) | 383 (19.2) | 292 (14.7) | 1503 (18.9) | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | |||||

| Employed | 1555 (77.9) | 1456 (72.7) | 1498 (75.3) | 1669 (83.9) | 6178 (77.4) | |

| Unemployed | 157 (7.9) | 265 (13.2) | 188 (9.4) | 122 (6.1) | 732 (9.2) | |

| Other (student, unpaid household work, retired) | 285 (14.3) | 281 (14.0) | 304 (15.3) | 198 (10.0) | 1068 (13.4) | |

| Social class | <0.001 | |||||

| High | 618 (30.9) | 650 (32.5) | 685 (34.4) | 757 (38.1) | 2710 (34.0) | |

| Medium | 477 (23.9) | 438 (21.9) | 462 (23.2) | 460 (23.1) | 1837 (23.0) | |

| Low | 820 (41.1) | 833 (41.6) | 725 (36.4) | 687 (34.5) | 3065 (38.4) | |

| Not classified/not working | 82 (4.1) | 81 (4.0) | 118 (5.9) | 85 (4.3) | 366 (4.6) | |

| Vaccine Hesitancy | Vaccine Refusal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude PR (CI 95%) | aPR (CI 95%) | Crude PR (CI 95%) | aPR (CI 95%) | |

| Total | Total | |||

| Year | ||||

| 2019 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2020 | 1.29 (0.96–1.73) | 1.29 (0.96–1.73) | 1.05 (0.69–1.59) | 1.04 (0.68–1.57) |

| 2021 | 2.18 (1.67–2.85) ** | 2.21 (1.69–2.88) ** | 0.38 (0.22–0.68) ** | 0.39 (0.22–0.68) ** |

| 2024 | 4.91 (3.86–6.25) ** | 5.04 (3.96–6.41) ** | 3.80 (2.72–5.31) ** | 4.00 (2.86–5.59) ** |

| Men | Men | |||

| Year | ||||

| 2019 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2020 | 2.00 (1.21–3.31) | 2.05 (1.24–3.34) ** | 1.40 (0.73–2.70) | 1.40 (0.72–2.71) |

| 2021 | 3.62 (2.28–5.76) ** | 3.76 (2.36–5.98) ** | 0.33 (0.12–0.91) * | 0.34 (0.12–0.93) * |

| 2024 | 7.83 (5.07–12.10) ** | 7.96 (5.15–12.31) ** | 4.73 (2.73–8.19) ** | 4.73 (2.71–8.27) ** |

| Women | Women | |||

| Year | ||||

| 2019 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2020 | 1.00 (0.69–1.44) | 0.97 (0.67–1.41) | 0.85 (0.49–1.47) | 0.83 (0.48–1.44) |

| 2021 | 1.58 (1.13–2.21) ** | 1.59 (1.14–2.22) ** | 0.41 (0.21–0.83) * | 0.42 (0.21–0.83) * |

| 2024 | 3.71 (2.77–4.96) ** | 3.80 (2.84–5.09) ** | 3.30 (2.16–5.03) ** | 3.56 (2.34–5.41) ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pichiule-Castañeda, M.; Serrano-de-la-Cruz, A.; Domínguez-Berjón, M.-F.; Gandarillas-Grande, A. Vaccine Attitudes Among Adults in a Southern European Region: Survey from Pre- to Post-COVID-19. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121204

Pichiule-Castañeda M, Serrano-de-la-Cruz A, Domínguez-Berjón M-F, Gandarillas-Grande A. Vaccine Attitudes Among Adults in a Southern European Region: Survey from Pre- to Post-COVID-19. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121204

Chicago/Turabian StylePichiule-Castañeda, Myrian, Alicia Serrano-de-la-Cruz, María-Felícitas Domínguez-Berjón, and Ana Gandarillas-Grande. 2025. "Vaccine Attitudes Among Adults in a Southern European Region: Survey from Pre- to Post-COVID-19" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121204

APA StylePichiule-Castañeda, M., Serrano-de-la-Cruz, A., Domínguez-Berjón, M.-F., & Gandarillas-Grande, A. (2025). Vaccine Attitudes Among Adults in a Southern European Region: Survey from Pre- to Post-COVID-19. Vaccines, 13(12), 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121204