Influencing Factors of Pregnant Women’s Willingness to Receive Influenza Vaccination in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Influencing Factors of Willingness to Receive Seasonal Influenza Vaccination

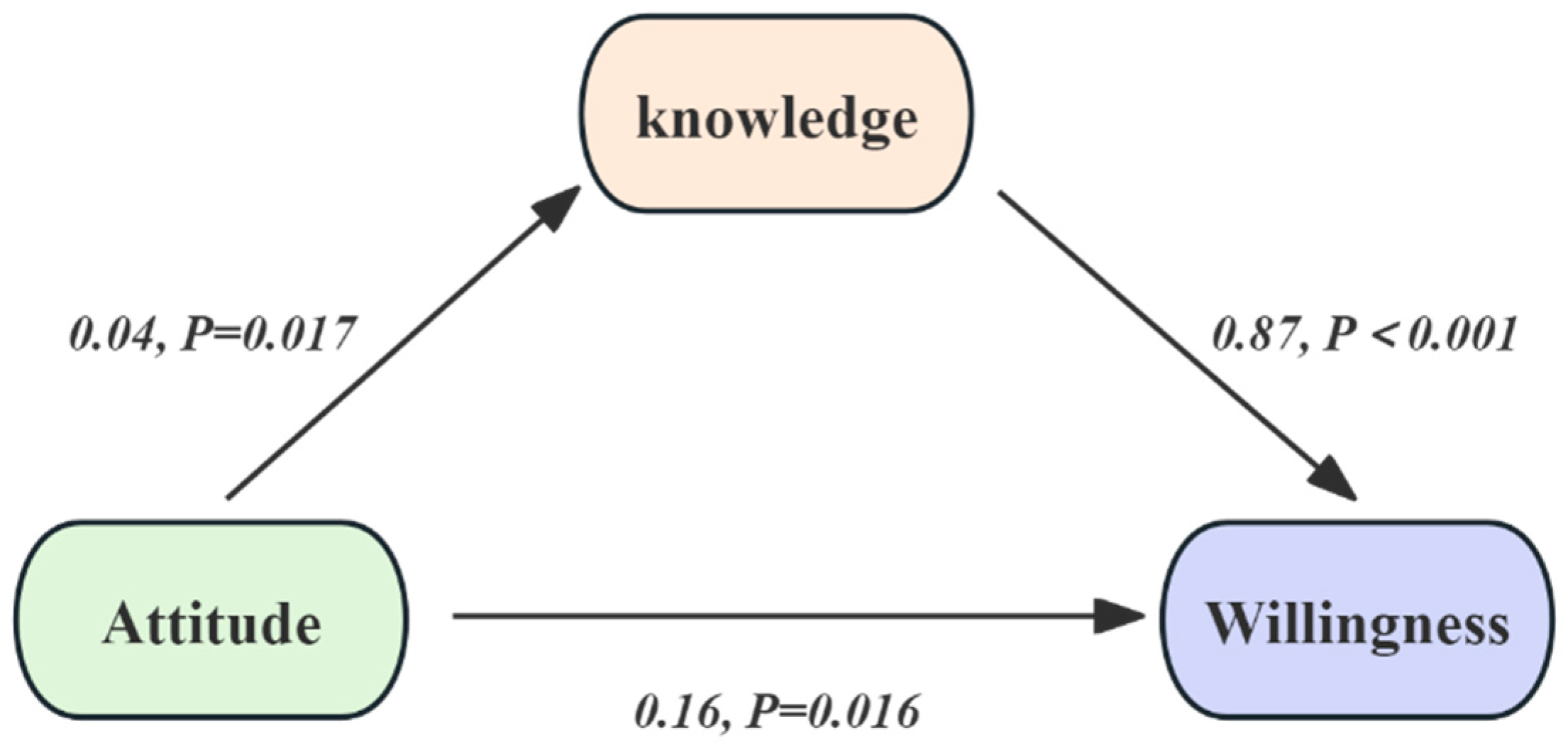

3.3. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, X.; Wang, T.; Hao, H.; D’Souza, R.R.; Strickland, M.J.; Warren, J.L.; Darrow, L.A.; Chang, H.H. Influenza Activity and Preterm Birth in the Atlanta Metropolitan Area: A Time-Series Analysis from 2010 to 2017. Epidemiology 2025, 36, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubizolles, C.; Barjat, T.; Chauleur, C.; Bruel, S.; Botelho-Nevers, E.; Gagneux-Brunon, A. Evaluation of intentions to get vaccinated against influenza, COVID 19, pertussis and to get a future vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus in pregnant women. Vaccine 2023, 41, 7342–7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohfuji, S.; Deguchi, M.; Tachibana, D.; Koyama, M.; Takagi, T.; Yoshioka, T.; Urae, A.; Fukushima, W.; Hirota, Y. Estimating influenza disease burden among pregnant women: Application of self-control method. Vaccine 2017, 35, 4811–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vygen-Bonnet, S.; Hellenbrand, W.; Garbe, E.; von Kries, R.; Bogdan, C.; Heininger, U.; Robl-Mathieu, M.; Harder, T. Safety and effectiveness of acellular pertussis vaccination during pregnancy: A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cayley, W.E., Jr. Vaccines for Preventing Influenza in Healthy Children, Healthy Adults, and Older Adults. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.G.; Kwong, J.C.; Regan, A.K.; Katz, M.A.; Drews, S.J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Klein, N.P.; Chung, H.; Effler, P.V.; Feldman, B.S.; et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Influenza-associated Hospitalizations During Pregnancy: A Multi-country Retrospective Test Negative Design Study, 2010–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2019, 68, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.B.; Clark, D.R.; Madhi, S.A.; Tapia, M.D.; Nunes, M.C.; Cutland, C.L.; Simoes, E.A.F.; Aqil, A.R.; Katz, J.; Tielsch, J.M.; et al. Efficacy, duration of protection, birth outcomes, and infant growth associated with influenza vaccination in pregnancy: A pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet. Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.M.; Dawood, F.S.; Grohskopf, L.A.; Ellington, S. Preventing Influenza Virus Infection and Severe Influenza Among Pregnant People and Infants. J. Womens Health 2024, 33, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakala, I.G.; Honda-Okubo, Y.; Fung, J.; Petrovsky, N. Influenza immunization during pregnancy: Benefits for mother and infant. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 3065–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper–November 2012. Relev. Epidemiol. Hebd. 2012, 87, 461–476.

- Couture, A.; Iuliano, A.D.; Chang, H.H.; Threlkel, R.; Gilmer, M.; O’Halloran, A.; Ujamaa, D.; Biggerstaff, M.; Reed, C. State-Level Influenza Hospitalization Burden in the United States, 2022–2023. Am. J. Public Health 2025, 115, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Tang, N.; Gao, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Qu, B. Knowledge and Willingness toward Vaccination among Pregnant Women: Comparison between Pertussis and Influenza. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, S.; Brooks, D.; Jorgensen, P.; Wijesinghe, P.; Cho, H.; Attia, R.; Doshi, R.; Nogareda, F.; Herring, B.; Dumolard, L.; et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination: A global review of national policies in 194 WHO member states in 2022. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulatoğlu, Ç.; Turan, G. Women’s knowledge and beliefs towards vaccination for influenza during pregnancy in Turkey and underlying factors of misinformation: A single-centre cross-sectional study. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabadi, A.; Dodds, L.; MacDonald, N.E.; Top, K.A.; Benchimol, E.I.; Kwong, J.C.; Ortiz, J.R.; Sprague, A.E.; Walsh, L.K.; Wilson, K.; et al. Association of Maternal Influenza Vaccination During Pregnancy with Early Childhood Health Outcomes. Jama 2021, 325, 2285–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, S.; Bouchet, J.; Costello, P.; Parker, J. Influenza vaccine uptake among at-risk adults (aged 16–64 years) in the UK: A retrospective database analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis-Kuberka, J.; Orczyk-Pawiłowicz, M. Maternal Vaccination and Neonatal Feeding Strategies Among Polish Women. Vaccines 2025, 13, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarna, M.; Pereira, G.F.; Foo, D.; Baynam, G.S.; Regan, A.K. The risk of major structural birth defects associated with seasonal influenza vaccination during pregnancy: A population-based cohort study. Birth Defects Res. 2022, 114, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar, D.; Anastassopoulou, A.; Poulsen Nautrup, B.; Schmidt-Ott, R.; Eichner, M.; Schwehm, M.; Dos Santos, G.; Ultsch, B.; Bekkat-Berkani, R.; von Krempelhuber, A.; et al. Cost-utility analysis of increasing uptake of universal seasonal quadrivalent influenza vaccine (QIV) in children aged 6 months and older in Germany. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2058304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, S.; Prabhakaran, A.O.; Dhakal, G.P.; Zangmo, C.; Gharpure, R.; Dawa, T.; Phuntsho, S.; Burkhardsmeier, B.; Saha, S.; Wangmo, D.; et al. Introducing seasonal influenza vaccine in Bhutan: Country experience and achievements. Vaccine 2023, 41, 7259–7264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehesh, M.; Gholamin, S.; Razavi, S.M.; Eskandari, A.; Vakili, H.; Rahnavardi Azari, M.; Wang, Y.; Gough, E.K.; Keshtkar-Jahromi, M. Influenza Vaccination and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Coronary Artery Diseases: A Placebo-Controlled Randomized Study, IVCAD. Vaccines 2025, 13, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, J.; LaSalle, G.; Pflugeisen, C.; Sherls-Jones, J.; Castañeda, H.; Zaragoza, G.; Smith, C.; Mays, J.; Villarreal, N. Practice, beliefs and intent in influenza vaccination among Hispanic patients during the pandemic: An interventional study. Vaccine 2025, 58, 127207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostrud, L.; Thelen, J.; Palatnik, A. Models of determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in non-pregnant and pregnant population: Review of current literature. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2138047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, D.M.; Silva, M.J.A.; Bispo, S.K.S.; da Silva, A.P.O.; Lima, K.V.B.; Ferreira, I.P.; Lima, L. Prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1622247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpas, D.; Stefanicka-Wojtas, D.; Soll-Morka, A.; Lomper, K.; Uchmanowicz, B.; Blahova, B.; Bredelytė, A.; Dumitra, G.G.; Hudáčková, V.; Javorska, K.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy and Immunization Patterns in Central and Eastern Europe: Sociocultural, Economic, Political, and Digital Influences Across Seven Countries. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2025, 18, 1911–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, W.J.; Achar, S.; Achar, J.; Dhamija, A.; Tai-Seale, M.; Strong, D. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Associations with gender, race, and source of health information. Fam. Syst. Health Collab. Fam. Healthc. 2022, 40, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Riccio, M.; Bechini, A.; Buscemi, P.; Bonanni, P.; On Behalf Of The Working Group, D.; Boccalini, S. Reasons for the Intention to Refuse COVID-19 Vaccination and Their Association with Preferred Sources of Information in a Nationwide, Population-Based Sample in Italy, before COVID-19 Vaccines Roll Out. Vaccines 2022, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushi, G.; Khatib, M.N.; S, R.J.; Kaur, I.; Sharma, A.; Iqbal, S.; Kumar, M.R.; Chauhan, A.S.; Vishwakarma, T.; Malik, P.; et al. Determinants of Malaria Vaccine Acceptance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Awareness, Acceptance, Hesitancy, and Willingness to Pay. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2025, 13, e70205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Khwaja, H.; Kalhoro, S.; Mehmood, J.; Qazi, M.F.; Abubakar, A.; Mohamed, S.; Khan, W.; Jehan, F.; Nisar, M.I. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward seasonal influenza vaccination among healthcare workers and pregnant women in Pakistan: A mixed methods approach. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2258627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, F.; Pelullo, C.P.; Della Polla, G.; Citrino, E.A.; Bianco, A. Immunization during pregnancy: Do healthcare workers recommend vaccination against influenza? Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1171142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selley, P.; Healy, D. The Health of Pregnant Women and Their Unborn Children- Neglected in Vaccine Development. Birth Defects Res. 2025, 117, e2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razai, M.S.; Ussher, M.; Goldsmith, L.; Hargreaves, S.; Oakeshott, P. Navigating vaccination in pregnancy: Qualitative study in 21 ethnically diverse pregnant women. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0310823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, A.; Yee, A.; Izikson, R.; Fireman, B.; Hansen, J.; Lewis, N.; Gandhi-Banga, S.; Selmani, A.; Talanova, O.; Kabler, H.; et al. Safety of quadrivalent recombinant influenza vaccine in pregnant persons and their infants. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2024, 4, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Immunization Advisory Committee, & Technical Working Group. Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2023-2024). Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi 2023, 44, 1507–1530. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Total (n = 1231) | Willing (n = 571) | Unwilling (n = 660) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30.0 ± 3.9 | 30.7 ± 3.9 | 30.8 ± 4.3 | 0.531 |

| Ethnicity | 0.479 | |||

| Han | 1105 (89.8%) | 510 (46.2%) | 595 (53.8%) | |

| Tujia ethnic group | 87 (7.1%) | 45 (51.7%) | 42 (48.3%) | |

| Others | 39 (3.2%) | 16 (41.0%) | 23 (59.0%) | |

| BMI | 24.2 ± 8.5 | 24.1 ± 8.4 | 24.4 ± 8.6 | 0.591 |

| Registered residence | 0.310 | |||

| Urban | 619 (50.3%) | 323 (48.9%) | 296 (51.8%) | |

| Rural | 612 (49.7%) | 337 (51.1%) | 275 (48.2%) | |

| Educational level | 571 | 660 | 0.003 | |

| Junior college and below | 536 (43.5%) | 226 (39.6%) | 310 (47.0%) | |

| Undergraduate | 587 (47.7%) | 287 (50.3%) | 300 (45.5%) | |

| Postgraduate and above | 108 (8.8%) | 58 (10.2%) | 50 (7.6%) | |

| Marriage status | 571 | 660 | 0.215 | |

| Married | 22 (1.8%) | 14 (2.5%) | 8 (1.2%) | |

| Unmarried | 1204 (97.8%) | 554 (97%) | 650 (98.5%) | |

| Divorced | 5 (0.4%) | 3 (0.5%) | 2 (0.3%) | |

| Occupation | 571 | 660 | 0.010 | |

| Public institutions | 611 (49.6%) | 310 (54.3%) | 301 (45.6%) | |

| Enterprise or private enterprise | 617 (50.1%) | 259 (45.4%) | 358 (54.2%) | |

| Student | 3 (0.2%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Annual income | 571 | 660 | 0.013 | |

| CNY ≤ 100,000 | 824 (66.9%) | 372 (65.1%) | 452 (68.5%) | |

| CNY 100,000–200,000 | 378 (30.7%) | 172 (30.1%) | 196 (29.7%) | |

| CNY ≥ 200,000 | 29 (2.4%) | 22 (3.9%) | 7 (1.1%) | |

| Number of pregnancies | 0.077 | |||

| 1 | 787 (63.9%) | 382 (66.9%) | 405 (61.4%) | |

| 2 | 367 (46.6%) | 123 (21.5%) | 183 (27.7%) | |

| ≥3 | 77 (21.0%) | 66 (11.6%) | 72 (10.9%) | |

| Gestational weeks | 24.9 ± 8.7 | 25.5 ± 9.0 | 25.4 ± 8.6 | 0.043 |

| Number of fetuses | 0.325 | |||

| Single fetus | 1166 (94.7%) | 537 (94.0%) | 629 (95.3%) | |

| Multiple fetuses | 65 (5.6%) | 34 (6.3%) | 31 (4.7%) | |

| Whether the prenatal checkup is normal | 0.416 | |||

| No | 50 (4.1%) | 26 (4.6%) | 24 (3.6%) | |

| Yes | 1181 (95.9%) | 545 (95.4%) | 636 (96.4%) | |

| History of spontaneous abortion | 0.404 | |||

| No | 1085 (88.1%) | 508 (89%) | 577 (87.4%) | |

| Yes | 146 (11.9%) | 63 (11%) | 83 (12.6%) | |

| History of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia | 0.123 | |||

| No | 1216 (98.8%) | 567 (99.3%) | 649 (98.3%) | |

| Yes | 15 (1.2%) | 4 (0.7%) | 11 (1.7%) | |

| History of gestational diabetes | 0.959 | |||

| No | 1113 (90.4%) | 516 (90.4%) | 597 (90.5) | |

| Yes | 118 (9.6%) | 55 (9.6%) | 63 (9.5%) | |

| Ever given birth to a abnormal fetus | 0.512 | |||

| No | 1184 (96.2%) | 547 (95.8%) | 637 (96.5%) | |

| Yes | 47 (3.8%) | 24 (4.2%) | 23 (3.5%) | |

| Ever given birth to a baby with low birth weight | 0.744 | |||

| No | 1210 (98.3%) | 562 (98.4%) | 648 (98.2%) | |

| Yes | 21 (1.7%) | 9 (1.6%) | 12 (1.8%) | |

| History of delivery difficulties | 0.060 | |||

| No | 1220 (99.1%) | 569 (99.6%) | 651 (98.6%) | |

| Yes | 11 (0.9%) | 2 (0.4%) | 9 (1.4%) | |

| History of premature birth | 0.431 | |||

| No | 1222 (99.3%) | 568 (99.5%) | 654 (99.1%) | |

| Yes | 9 (0.7%) | 3 (0.5%) | 6 (0.9%) | |

| History of immune diseases | 0.769 | |||

| No | 1166 (94.7%) | 542 (94.9%) | 624 (94.5%) | |

| Yes | 65 (5.3%) | 29 (5.1%) | 36 (5.5%) | |

| History of malignant tumors | 0.362 | |||

| No | 1219 (99.0%) | 567 (99.3%) | 652 (98.8%) | |

| Yes | 12 (1.0%) | 4 (0.7%) | 8 (1.2%) | |

| History of severe allergies | 0.757 | |||

| No | 1213 (98.5%) | 562 (98.4%) | 651 (98.6%) | |

| Yes | 18 (1.5%) | 9 (1.6%) | 9 (1.4%) | |

| History of immune deficiency diseases | 0.818 | |||

| No | 1221 (98.2%) | 566 (99.1%) | 655 (99.2%) | |

| Yes | 10 (0.8%) | 5 (0.9%) | 5 (0.8%) | |

| History of major systemic disease | 0.177 | |||

| No | 1217 (98.9%) | 562 (98.4%) | 655 (99.2%) | |

| Yes | 14 (1.1%) | 9 (1.6%) | 5 (0.8%) | |

| History of progressive neurological diseases | 0.918 | |||

| No | 1229 (99.8%) | 570 (99.8%) | 659 (99.8%) | |

| Yes | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Ever heard of the flu vaccine | 0.004 | |||

| No | 241 (19.6%) | 92 (16.1%) | 149 (22.6%) | |

| Yes | 990 (80.4%) | 479 (83.9%) | 511 (77.4%) | |

| Pregnant women’s knowledge about the influenza vaccine | 0.000 | |||

| No | 740 (60.1%) | 279 (48.9%) | 461 (69.8%) | |

| Yes | 491 (39.9%) | 292 (51.1%) | 199 (30.2%) | |

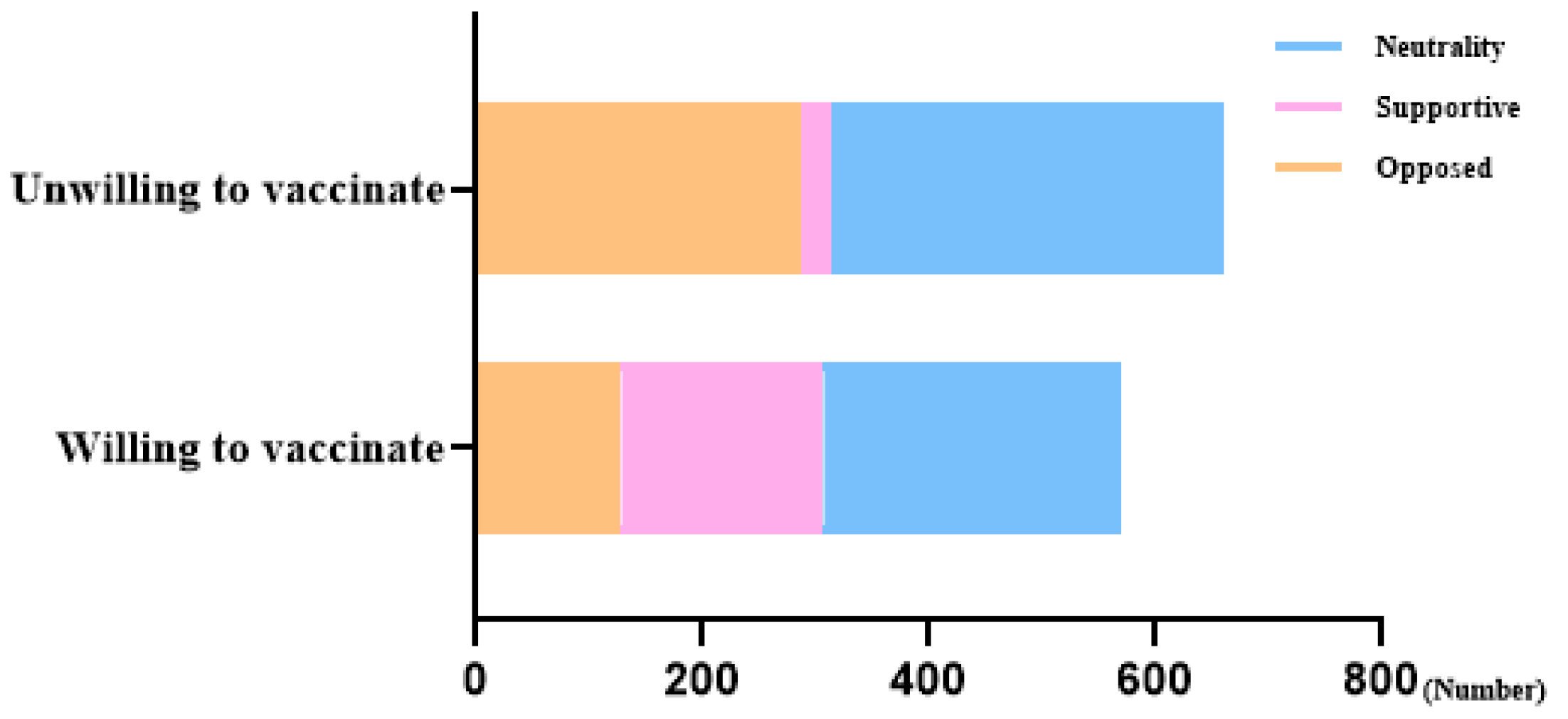

| Attitudes towards influenza vaccination for pregnant women | 0.000 | |||

| Opposed | 414 (33.6%) | 128 (22.4%) | 286 (43.3%) | |

| Supportive | 206 (16.7%) | 179 (31.3%) | 27 (4.1%) | |

| Neutrality | 611 (49.6%) | 264 (46.2%) | 347 (52.6%) | |

| The acceptable price of the vaccine | 0.000 | |||

| CNY ≤ 200 | 768 (62.4%) | 306 (53.6%) | 462 (70.0%) | |

| CNY 200–500 | 413 (33.5%) | 238 (41.7%) | 175 (26.5%) | |

| CNY ≥ 500 | 50 (4.1%) | 27 (4.7%) | 23 (3.5%) |

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Coefficient | OR (95%CI) | p | β-Coefficient | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Educational level | 0.022 | 0.802 | ||||

| Junior college and below | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| Undergraduate | 0.27 | 1.31 (1.04–1.66) | 0.024 | 0.02 | 1.11 (0.82–1.49) | 0.510 |

| Postgraduate and above | 0.46 | 1.59 (1.05–2.41) | 0.028 | −0.04 | 1.10 (0.64–1.91) | 0.726 |

| Occupation | 0.007 | 0.453 | ||||

| Public institutions | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| Enterprise or private enterprise | −0.35 | 0.70 (0.56–0.88) | 0.002 | −0.22 | 0.87 (0.66–1.17) | 0.358 |

| Student | 0.66 | 1.94 (0.18–21.5) | 0.589 | 1.02 | 2.87 (0.24–34.50) | 0.406 |

| Annual income | 0.009 | 0.015 | ||||

| CNY ≤ 100,000 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| CNY 100,000–200,000 | 0.07 | 1.07 (0.84–1.37) | 0.587 | −0.28 | 0.76 (0.56–1.03) | 0.076 |

| CNY ≥ 200,000 | 1.34 | 3.82 (1.61–9.04) | 0.002 | 0.97 | 2.65 (1.02–6.85) | 0.045 |

| Number of pregnancies | 0.039 | 0.096 | ||||

| 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| 2 | −0.31 | 0.73 (0.57–0.94) | 0.015 | −0.27 | 0.76 (0.57–1.01) | 0.062 |

| ≥3 | 0.08 | 1.09 (0.68–1.74) | 0.724 | 0.20 | 1.22 (0.72–2.06) | 0.454 |

| Gestational weeks | 0.00 | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.799 | |||

| History of delivery difficulties | ||||||

| No | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| Yes | −1.37 | 0.25 (0.06–1.18) | 0.081 | −2.28 | 0.10 (0.02–0.62) | 0.013 |

| Ever heard of the flu vaccine | ||||||

| No | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.42 | 1.52 (1.14–2.03) | 0.005 | 0.14 | 1.15 (0.81–1.63) | 0.43 |

| Pregnant women’s knowledge about the influenza vaccine | ||||||

| No | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.89 | 2.43 (1.92–3.06) | 0.000 | 0.52 | 1.69 (1.28–2.23) | 0.000 |

| Attitudes towards influenza vaccination for pregnant women | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| Opposed | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| Supportive | 2.70 | 14.81 (9.40–23.35) | 0.000 | 2.59 | 13.35 (8.26–21.55) | 0.000 |

| Neutrality | 0.53 | 1.70 (1.31–2.21) | 0.000 | 0.48 | 1.61 (1.22–2.12) | 0.001 |

| The acceptable price of the vaccine | 0.000 | |||||

| CNY ≤ 200 | Reference | 1 | Reference | 1 | ||

| CNY 200–500 | 0.72 | 2.05 (1.61–2.62) | 0.000 | 0.76 | 2.15 (1.64–2.82) | 0.000 |

| CNY ≥ 500 | 0.57 | 1.77 (1.00–3.15) | 0.051 | 0.83 | 2.29 (1.23–4.27) | 0.009 |

| Model | Total Association | Direct Association | Indirect Association | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | Proportion Mediated | |

| Model 1: mediated via price | |||||||

| Model 1 | 0.19 (0.08–0.30) | 0.005 | 0.19 (0.09–0.30) | 0.003 | −0.01 (−0.03–0.01) | 0.520 | NA |

| Model 3: mediated via history of delivery difficulties | |||||||

| Model 2 | 0.18 (0.08–0.30) | 0.006 | 0.19 (0.09–0.30) | 0.003 | −0.01 (−0.05–0.000) | 0.702 | NA |

| Model 3: mediated via knowledge of the influenza vaccine | |||||||

| Model 3 | 0.19 (0.08–0.30) | 0.005 | 0.16 (0.05–0.27) | 0.016 | 0.03 (0.01–0.06) | 0.025 | 15.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, Y.; Shan, N.; Wang, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Qi, H.; Li, J. Influencing Factors of Pregnant Women’s Willingness to Receive Influenza Vaccination in China. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121194

Tao Y, Shan N, Wang Y, Sun M, Zhang L, Yang L, Chen L, Qi H, Li J. Influencing Factors of Pregnant Women’s Willingness to Receive Influenza Vaccination in China. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121194

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Yi, Nan Shan, Yan Wang, Minghong Sun, Lijuan Zhang, Lihong Yang, Lei Chen, Hongbo Qi, and Junlong Li. 2025. "Influencing Factors of Pregnant Women’s Willingness to Receive Influenza Vaccination in China" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121194

APA StyleTao, Y., Shan, N., Wang, Y., Sun, M., Zhang, L., Yang, L., Chen, L., Qi, H., & Li, J. (2025). Influencing Factors of Pregnant Women’s Willingness to Receive Influenza Vaccination in China. Vaccines, 13(12), 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121194