Integrating Science Media Literacy, Motivational Interviewing, and Neuromarketing Science to Increase Vaccine Education Confidence among U.S. Extension Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Rationale for Approach to Needs Assessment for Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy

1.1.2. Elements of the Needs Assessment: Science Media Literacy

1.1.3. Elements of the Needs Assessment: Motivational Interviewing

1.1.4. Elements of the Needs Assessment: Neuromarketing Science

- The effects of media entirely emerge from cognitive and emotional processes embodied in the human brain and nervous system.

- Humans are, first and foremost, motivational and emotional information processors.

- Humans are limited capacity information processors.

1.1.5. Summary of the Needs Assessment Elements

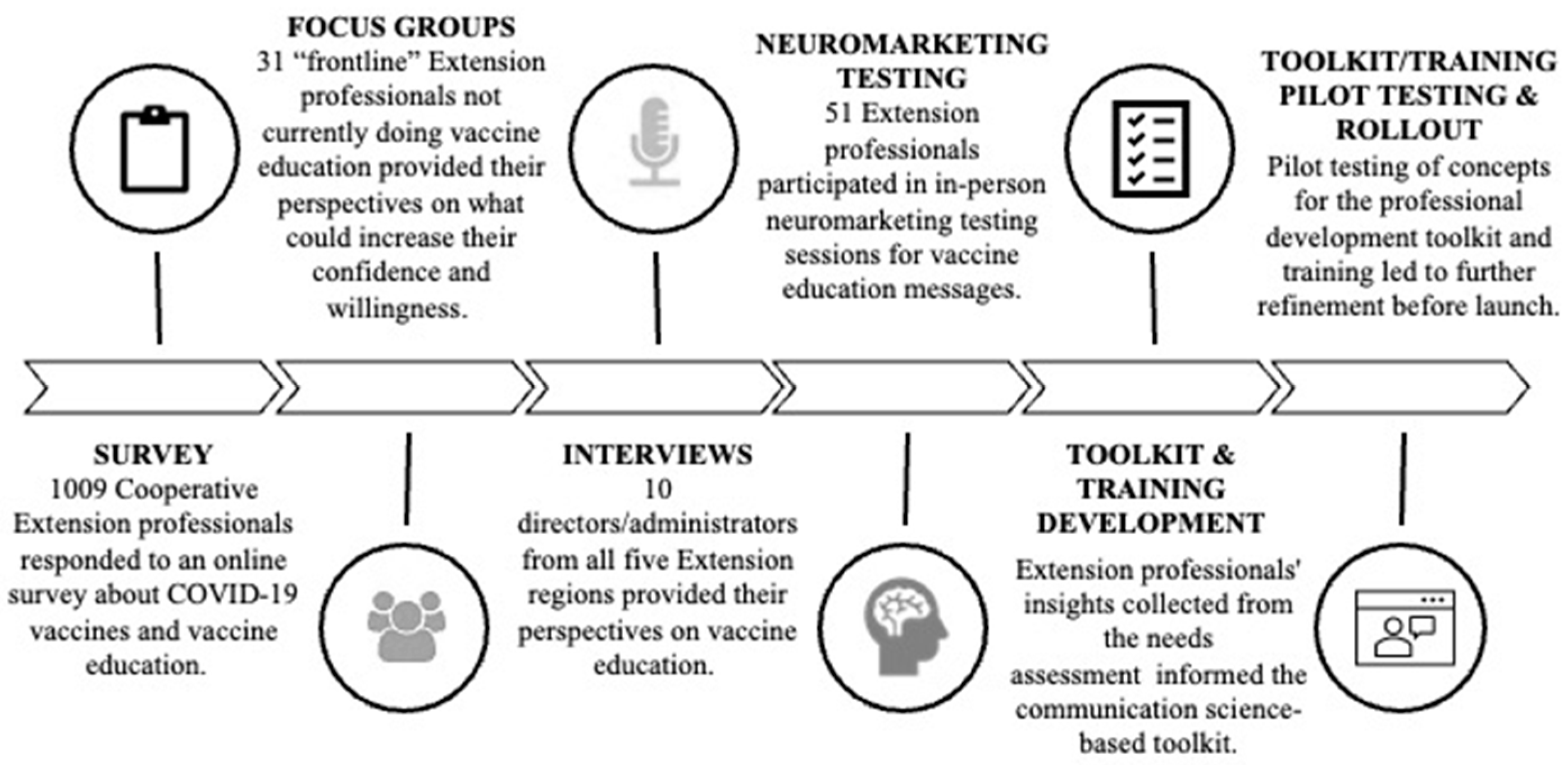

2. Materials and Methods

Survey Methods

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results

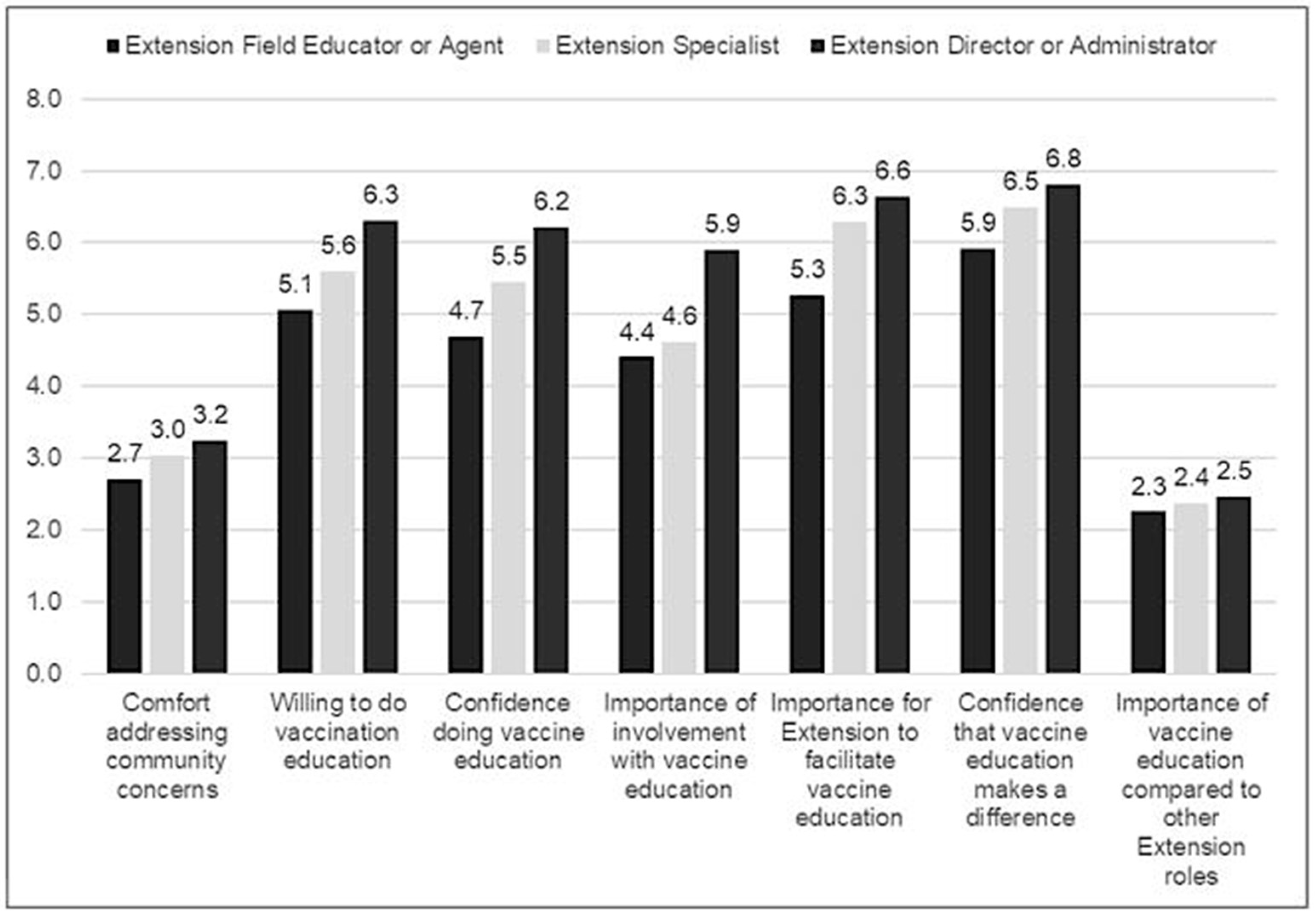

3.1.1. Need 1. Tailor Training Based on Extension Roles

3.1.2. Need 2. Prioritize Preserving Community Trust and Professional Credibility

3.1.3. Need 3. Establish Connections with Medical Experts

3.1.4. Need 4. Strengthen Science Media Literacy Skills to Counter Misinformation and Communicate Emerging Science

3.2. Qualitative Methods

3.2.1. Focus Groups

3.2.2. Focus Groups Results

“I feel that if we want to be known for community wellness work, we should not sidestep an issue with such widespread impact on community wellness”.

“I understand vaccines and the science behind them. I educate my producers about Livestock vaccines all the time”.

“I would be willing to conduct vaccine education if it treats individuals who are afraid of vaccination or paranoid with respect and does not involve intimidation, humiliation, or even persuasion. Just share general information about vaccinations, how they work, and how they are developed”.

“I would like honest information that takes the emotional appeal out of this. People have picked sides and don’t seem willing to discuss holes in the message. Personal experiences of people around me do not match mainstream messaging. That creates fear and makes me slow to tell others what they should do”.

“The peer pressure of partisan politics within extension has made it difficult to continue pride in the work we do. Public health should have never become political, yet here we are”.

“I do not wish to be berated by members of the public as part of my job. I am a horticulturist, not a public health administrator”.

3.3. Expert Interviews

3.3.1. Expert Interview Methods

3.3.2. Expert Interview Results

3.4. Neuromarketing Science

3.4.1. Neuromarketing Science Methods

3.4.2. Neuromarketing Content Testing Results

3.5. Pilot Workshops

3.5.1. Pilot Workshop Methods

3.5.2. Pilot Workshop Results

3.5.3. Key Strengths Identified in the Pilot Workshops

3.5.4. Key Challenges and Opportunities Identified in the Workshops

3.6. Integrated Findings from the Survey, Focus Groups, In-Depth Interviews, Neuromarketing Content Testing, and Pilot Testing

3.6.1. The Integrated Model of Sustainable Health Decision-Making

3.6.2. Getting to the Heart and Mind of the Matter Toolkit

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, E.; Fredricks, K.; Woc-Colburn, L.; Bottazzi, M.E.; Weatherhead, J. Disproportionate Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immigrant Communities in the United States. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, J.T.; McConnell, K.; Burow, P.B.; Pofahl, K.; Merdjanoff, A.A.; Farrell, J. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Rural America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 2019378118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, D.B.G.; Shah, A.; Doubeni, C.A.; Sia, I.G.; Wieland, M.L. The Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 72, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafadar, A.H.; Tekeli, G.G.; Jones, K.A.; Stephan, B.; Dening, T. Determinants for COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the General Population: A Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Public Health 2023, 31, 1829–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kricorian, K.; Civen, R.; Equils, O. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Misinformation and Perceptions of Vaccine Safety. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1950504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerretsen, P.; Kim, J.; Caravaggio, F.; Quilty, L.; Sanches, M.; Wells, S.; Brown, E.E.; Agic, B.; Pollock, B.G.; Graff-Guerrero, A. Individual Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, C.; Matthews, R.; Kreps, K.; Thornal, D.; McFall, D.; Sudduth, D.; Parisi, M. Extension-Clinical Approach to COVID-19 Testing and Vaccination. J. Ext. 2024, 61, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, A.; Dickinson, W.P.; Fagnan, L.J.; Duffy, F.D.; Parchman, M.L.; Rhyne, R.L. The Role of Health Extension in Practice Transformation and Community Health Improvement: Lessons from 5 Case Studies. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, 17 (Suppl. S1), S67–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperative Extension History|NIFA. Available online: https://www.nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/how-we-work/extension/cooperative-extension-history (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Braun, B.; Bruns, K.; Cronk, L.; Fox, L.K.; Koukel, S.; Le Menestrel, S.; Lord, S.M.; Reeves, C.; Rennekamp, R.; Rice, C.; et al. Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Health and Wellness; National Institute of Food and Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.nifa.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource/Cooperative_extensionNationalFrameworkHealth.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Burton, D.; Canto, A.; Coon, T.; Eschbach, C.; Gutter, M.; Jones, M.; Kennedy, L.; Martin, K.; Mitchell, A.; O’Neal, L.; et al. Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Health Equity and Well Being; [Report of the Health Innovation Task Force]; Extension Committee on Organization and Policy: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.aplu.org/wp-content/uploads/202120EquityHealth20Full.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Rodgers, M.; Downey, L.; Osborne, I. Extension Collaborative on Immunization Teaching and Engagement (EXCITE) Annual Report: Year Two: June 1, 2022–May 30, 2023. Extension Foundation. 2023. Available online: https://extension.org/national-programs-services/excite/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Brehm, J.W. Psychological Reactance: Theory and Applications. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1989, 16, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Quick, B.L.; Shen, L.; Dillard, J.P. Reactance Theory and Persuasion. In The SAGE Handbook of Persuasion: Developments in Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Dillard, J.P., Shen, L., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Core Principles. NAMLE. Available online: https://namle.org/resources/core-principles/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Austin, E.W.; Austin, B.W.; Borah, P.; Domgaard, S.; McPherson, S.M. How Media Literacy, Trust of Experts and Flu Vaccine Behaviors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 37, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, P.; Brunton-Smith, I.; Jackson, J. Trust in Science, Social Consensus and Vaccine Confidence. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lee, W.; Lin, F. Infodemic, Institutional Trust, and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Cross-National Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmann, M.; Reed, A.C.; Scott, M.; Presseau, J.; Heer, C.; May, K.; Ramzy, A.; Huynh, C.N.; Skidmore, B.; Welch, V.; et al. Exploring COVID-19 Education to Support Vaccine Confidence amongst the General Adult Population with Special Considerations for Healthcare and Long-Term Care Staff: A Scoping Review. Campbell. Syst. Rev. 2023, 19, e1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, E.W.; Pinkleton, B.E.; Austin, B.W.; Van de Vord, R. The Relationships of Information Efficacy and Media Literacy Skills to Knowledge and Self-Efficacy for Health-Related Decision Making. J. Am. Coll. Health 2012, 60, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, A.M.; Uscinski, J.E.; Klofstad, C.; Stoler, J. The Different Forms of COVID-19 Misinformation and Their Consequences. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinform. Rev. 2020, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, B.A.; Montgomery, J.M.; Guess, A.M.; Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J. Overconfidence in News Judgments Is Associated with False News Susceptibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019527118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, D. How Covid-19 Misinformation Is still Going Viral|CNN Business. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/08/tech/covid-viral-misinformation/index.html (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Austin, E.W.; Austin, B.W.; Willoughby, J.F.; Amram, O.; Domgaard, S. How Media Literacy and Science Media Literacy Predicted the Adoption of Protective Behaviors Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-H.; Cho, H.; Hwang, Y. Media Literacy Interventions: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, Z.; Sibalis, A.; Sutherland, J.E. Are Media Literacy Interventions Effective at Changing Attitudes and Intentions towards Risky Health Behaviors in Adolescents? A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Adolesc. 2018, 67, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S.; Maibach, E.; Leiserowitz, A. Exposure to Scientific Consensus does not cause Psychological Reactance. Environ. Commun. 2023, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Gai, X.; Zhou, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Media Literacy Interventions for Deviant Behaviors. Comput. Educ. 2019, 139, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calac, A.J.; Southwell, B.G. How Misinformation Research Can Mask Relationship Gaps That Undermine Public Health Response. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2022, 36, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbrey, B.E.; The Disinformation Dozen and Media Misinformation on Science and Vaccinations. The Center for Countering Digital Hate. 2021. Available online: https://counterhate.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/210324-The-Disinformation-Dozen.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change and Grow, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R.; Butler, C. Motivational Interviewing in Healthcare: Helping Patients Change Behavior, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bidkhanian, P. Motivational Interviewing Technique as a Means of Decreasing Vaccine Hesitancy in Children and Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogordan, C.; Fressard, L.; Ramalli, L.; Rebaudet, S.; Malfait, P.; Dutrey-Kaiser, A.; Attalah, Y.; Roy, D.; Berthiaume, P.; Gagneur, A.; et al. Motivational Interview-Based Health Mediator Interventions Increase Intent to Vaccinate among Disadvantaged Individuals. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2261687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagneur, A. Motivational Interviewing: A Powerful Tool to Address Vaccine Hesitancy. Can. Commun. Dieases Rep. 2020, 46, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, A.J.; Lee, J.; Small, J.W.; Sibley, M.; Owens, J.S.; Skidmore, B.; Johnson, L.; Bradshaw, C.P.; Moyers, T.B. Mechanisms of Motivational Interviewing: A Conceptual Framework to Guide Practice and Research. Prev. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Prev. Res. 2021, 22, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magill, M.; Apodaca, T.R.; Borsari, B.; Gaume, J.; Hoadley, A.; Gordon, R.E.F.; Tonigan, J.S.; Moyers, T. A Meta-Analysis of Motivational Interviewing Process: Technical, Relational, and Conditional Process Models of Change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 86, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassman, S.; Kottsieper, P.; Zuckoff, A.; Gosch, E.A. Motivational Interviewing and Recovery: Experiences of Hope, Meaning, and Empowerment. Adv. Dual Diagn. 2013, 6, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.C.; Ingersoll, K.S. Beyond Cognition: Broadening the Emotional Base of Motivational Interviewing. J. Psychother. Integr. 2008, 18, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H.; Campbell, P.; Maxwell, M.; O’Carroll, R.E.; Dombrowski, S.U.; Williams, B.; Cheyne, H.; Coles, E.; Pollock, A. Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on Adult Behaviour Change in Health and Social Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.K.; Rosenfeld, A.G.; Bennett, J.A.; Potempa, K. Heart-to-Heart: Promoting Walking in Rural Women Through Motivational Interviewing and Group Support. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2007, 22, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnicow, K.; Baskin, M.L.; Rahotep, S.S.; Periasamy, S.; Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing in health promotion and behavioral medicine. In Handbook of Motivational Counseling: Concepts, Approaches, and Assessment, 1st ed.; Cox, W.M., Klinger, E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2004; pp. 457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Radunovich, H.L.; Smith, S.R.; Ontai, L.; Hunter, C.; Cannella, R. The Role of Partner Support in the Physical and Mental Health of Poor, Rural Mothers. J. Rural Ment. Health 2017, 41, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remley, D. A Conversation Tool for Assessing a Food Pantry’s Readiness to Address Diet-Related Chronic Diseases. J. Ext. 2017, 55, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M.; Lane, E.; Dye, C.; Matthews, R.; McFall, D.; Bain, E.; Sherrill, W. Traditional and Virtual Hypertension Self-Management Health Education Program Delivered Through Cooperative Extension. J. Hum. Sci. Ext. 2022, 10, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.S.; Nisbet, E.C. Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Commun. Res. 2011, 39, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, T.G.L.A.; Hameleers, M. Fighting Biased News Diets: Using News Media Literacy Interventions to Stimulate Online Cross-Cutting Media Exposure Patterns. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 3156–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, R.; Bolls, P.D. Psychophysiological Measurement and Meaning: Cognitive and Emotional Processing of Media; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Genco, S.J.; Pohlmann, A.P.; Steidl, P. Neuromarketing for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons Canada Ltd.: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-I.; Lee, Y.-J.; Bolls, P.D. Media Psychophysiology and Strategic Communications: A Scientific Paradigm for Advancing Theory and Research Grounded in Evolutionary Psychology. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2023, 17, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varan, D.; Lang, A.; Barwise, P.; Weber, R.; Bellman, S. How Reliable Are Neuromarketers’ Measures of Advertising Effectiveness?: Data from Ongoing Research Holds No Common Truth among Vendors. J. Advert. Res. 2015, 55, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolls, P.D.; Weber, R.; Lang, A.; Potter, R.F. Media Psychophysiology and Neuroscience: Brining Brain Science into Media Processes and Effects Research. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 4th ed.; Oliver, M.B., Raney, A.A., Bryant, J., Eds.; Routledge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A. Using the Limited Capacity Model of Motivated Mediated Message Processing to Design Effective Cancer Communication Messages. J. Commun. 2006, 56, S57–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A. How the LC4MP Became the DHCCST: An Epistemological Fairy Tale. In The Handbook of Communication Science and Biology, 1st ed.; Floyd, K., Weber, R., Eds.; Routledge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 397–408. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, B.; Current, N. How to Make Online News ‘Brain Friendly’; Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute, University of Missouri: Columbia, MO, USA; Available online: https://rjionline.org/how-to/how-to-make-online-news-brain-friendly/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Extension Professionals’ Creed|OSU Extension. Available online: https://extension.osu.edu/about/mission-vision-values/extension-professionals-creed (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th ed.; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, L.L.; Rosson, H.; Weeks, P.P. Women Faculty in Postsecondary Agricultural and Extension Education: A Fifteen Year Update. J. Agric. Educ. 2019, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, E.W.; Borah, P.; Domgaard, S. COVID-19 Disinformation and Political Engagement among Communities of Color: The Role of Media Literacy. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinform. Rev. 2021, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClune, B.; Jarman, R. Critical Reading of Science-Based News Reports: Establishing a Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes Framework. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2010, 32, 727–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, C.T.; Pimentel, D.R.; Osborne, J. To Fight Misinformation, We Need to Teach that Science Is Dynamic. Scientific American 2024. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/to-fight-misinformation-we-need-to-teach-that-science-is-dynamic/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Kenny, D.A.; Kaniskan, B.; McCoach, D.B. The Performance of RMSEA in Models with Small Degrees of Freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 2015, 44, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, E.W.; Austin, B.W.; Bolls, P.; Sheftel, A.; Rose, P.; Edwards, Z.; O’Donnell, N.H.; Mu, D.; Sutherland, A.D.; Domgaard, S.; et al. Getting to the Heart and Mind of the Matter: A Toolkit to Build Confidence as a Trusted Messenger of Health Information, 4th ed.; EXCITE (Extension Collaborative on Immunization Teaching and Engagement) Extension Foundation: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2024; Available online: https://8907224.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/8907224/EXCITE%20WSU%20Toolkit/Getting%20to%20the%20Heart%20and%20Mind%20of%20the%20Matter%20Toolkit%204th%20Edition.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Rodgers, M.; Downey, L.; Osborne, I. Extension Collaborative on Immunization Teaching and Engagement (EXCITE) Pilot Projects—Final Report: June 2021–May 2023; Extension Foundation: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2024; Available online: https://8907224.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/8907224/FINAL%20EXCITE%20NARRATIVE%20REPORT.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Bean, S.J. Emerging and Continuing Trends in Vaccine Opposition Website Content. Vaccine 2011, 29, 1874–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendau, A.; Plag, J.; Petzold, M.B.; Ströhle, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Related Fears and Anxiety. Int. Immunopharmacol 2021, 97, 107724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-Y.S.; Budenz, A. Considering Emotion in COVID-19 Vaccine Communication: Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy and Fostering Vaccine Confidence. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 1718–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, C.J.; West, T.N.; Zhou, J.; Tan, K.R.; Prinzing, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Positive Emotions Co-Experienced with Strangers and Acquaintances Predict COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions through Prosocial Tendencies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 346, 116671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington State EXCITE TEAM (Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA); Rodgers, M. (Extension Foundation, Kansas City, MO, USA). Personal communication, 2024.

- Brown, C.C.; Young, S.G.; Pro, G.C. COVID-19 Vaccination Rates Vary by Community Vulnerability: A County-Level Analysis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4245–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, S.M.; Demeke, J.; Dada, D.; Wilton, L.; Wang, M.; Vlahov, D.; Nelson, L.E. Confidence and Hesitancy During the Early Roll-out of COVID-19 Vaccines Among Black, Hispanic, and Undocumented Immigrant Communities: A Review. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2022, 99, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | Mean | St. D | n | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to Do Vaccine Education (alpha = 0.857) | 10-point Likert Scale (1 = Not at all to 10 = Very). | |||

| 5.38 | 3.28 | 886 | |

| 5.17 | 3.15 | 852 | |

| Efficacy and Trust for Vaccine Education (alpha = 0.89) | 4-point Likert Scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree or 1 = Not at all to 4 = Very much). | |||

| 2.93 | 0.980 | 813 | |

| 2.49 | 0.778 | 819 | |

| 2.75 | 0.953 | 815 | |

| 3.15 | 1.04 | 841 | |

| Willingness to Speak Out (alpha = 0.915) If the topic of COVID-19 vaccines came up in these settings, how willing would you be to join in the conversation? | 4-point Likert Scale (1 = Very unwilling to 4 = Very willing). | |||

| 2.74 | 0.919 | 752 | |

| 3.11 | 0.841 | 750 | |

| 2.68 | 0.968 | 749 | |

| 2.67 | 0.981 | 749 | |

| Comfort in Addressing Misinformation | 5-point Likert Scale (1 = Very Uncomfortable to 5 = Very comfortable. | |||

| 2.86 | 1.25 | 839 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Willingness to do Vaccine Education | - | ||||||

| 2. Willingness to Speak-Out | 0.614 ** | - | |||||

| 3. Science Media Literacy for Source | −0.008 | −0.011 | - | ||||

| 4. Science Media literacy for Content | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.934 | - | |||

| 5.Perceived Severity of COVID-19 | 0.421 ** | 0.257 ** | 0.054 | 0.0350 | - | ||

| 6. Trust in Public Health Agencies | 0.576 ** | 0.363 ** | −0.092 | −0.099 | 0.518 ** | - | |

| 7. Willingness to Address Misinformation | 0.496 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.162 ** | 0.132 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.325 ** | - |

| Measures | Mean | St. D | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Science Media Literacy for Sources (alpha = 0.91) | |||

| I check whether those who create science news know about the topic. | 3.72 | 1.33 | 8.13 |

| I think about what point of view a science broadcaster or writer is trying to support. | 4.12 | 1.27 | 811 |

| I look to see if those who share science news on social media have checked the accuracy of their facts. | 3.65 | 1.41 | 794 |

| I think about whether sources of science news have my best interests in mind. | 4.00 | 1.33 | 807 |

| I think about whether those who provide science information might be doing so to gain power or profit. | 3.94 | 1.41 | 812 |

| I get science news from multiple sources to make sure I get the full story. | 4.20 | 1.21 | 809 |

| Science Media Literacy for Content (alpha = 0.90) | |||

| I think about how scientists can draw different conclusions from the same science facts. | 3.97 | 1.20 | 787 |

| I check to see if a science fact in a news story is backed up by a credible source. | 4.10 | 1.21 | 784 |

| I check to see if a picture or graph accurately matches the scientific information it represents. | 3.86 | 1.27 | 785 |

| I check to see if the science news I read is up to date. | 4.23 | 1.20 | 777 |

| I think about whether a news story with real science facts could still lead to a false conclusion. | 3.82 | 1.20 | 782 |

| I have changed my thinking about a science topic when I received new information. | 3.62 | 1.04 | 782 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Austin, E.W.; O’Donnell, N.; Rose, P.; Edwards, Z.; Sheftel, A.; Domgaard, S.; Mu, D.; Bolls, P.; Austin, B.W.; Sutherland, A.D. Integrating Science Media Literacy, Motivational Interviewing, and Neuromarketing Science to Increase Vaccine Education Confidence among U.S. Extension Professionals. Vaccines 2024, 12, 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12080869

Austin EW, O’Donnell N, Rose P, Edwards Z, Sheftel A, Domgaard S, Mu D, Bolls P, Austin BW, Sutherland AD. Integrating Science Media Literacy, Motivational Interviewing, and Neuromarketing Science to Increase Vaccine Education Confidence among U.S. Extension Professionals. Vaccines. 2024; 12(8):869. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12080869

Chicago/Turabian StyleAustin, Erica Weintraub, Nicole O’Donnell, Pamela Rose, Zena Edwards, Anya Sheftel, Shawn Domgaard, Di Mu, Paul Bolls, Bruce W. Austin, and Andrew D. Sutherland. 2024. "Integrating Science Media Literacy, Motivational Interviewing, and Neuromarketing Science to Increase Vaccine Education Confidence among U.S. Extension Professionals" Vaccines 12, no. 8: 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12080869

APA StyleAustin, E. W., O’Donnell, N., Rose, P., Edwards, Z., Sheftel, A., Domgaard, S., Mu, D., Bolls, P., Austin, B. W., & Sutherland, A. D. (2024). Integrating Science Media Literacy, Motivational Interviewing, and Neuromarketing Science to Increase Vaccine Education Confidence among U.S. Extension Professionals. Vaccines, 12(8), 869. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12080869