COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among University Students and Lecturers in Different Provinces of Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Questionnaire Development

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine

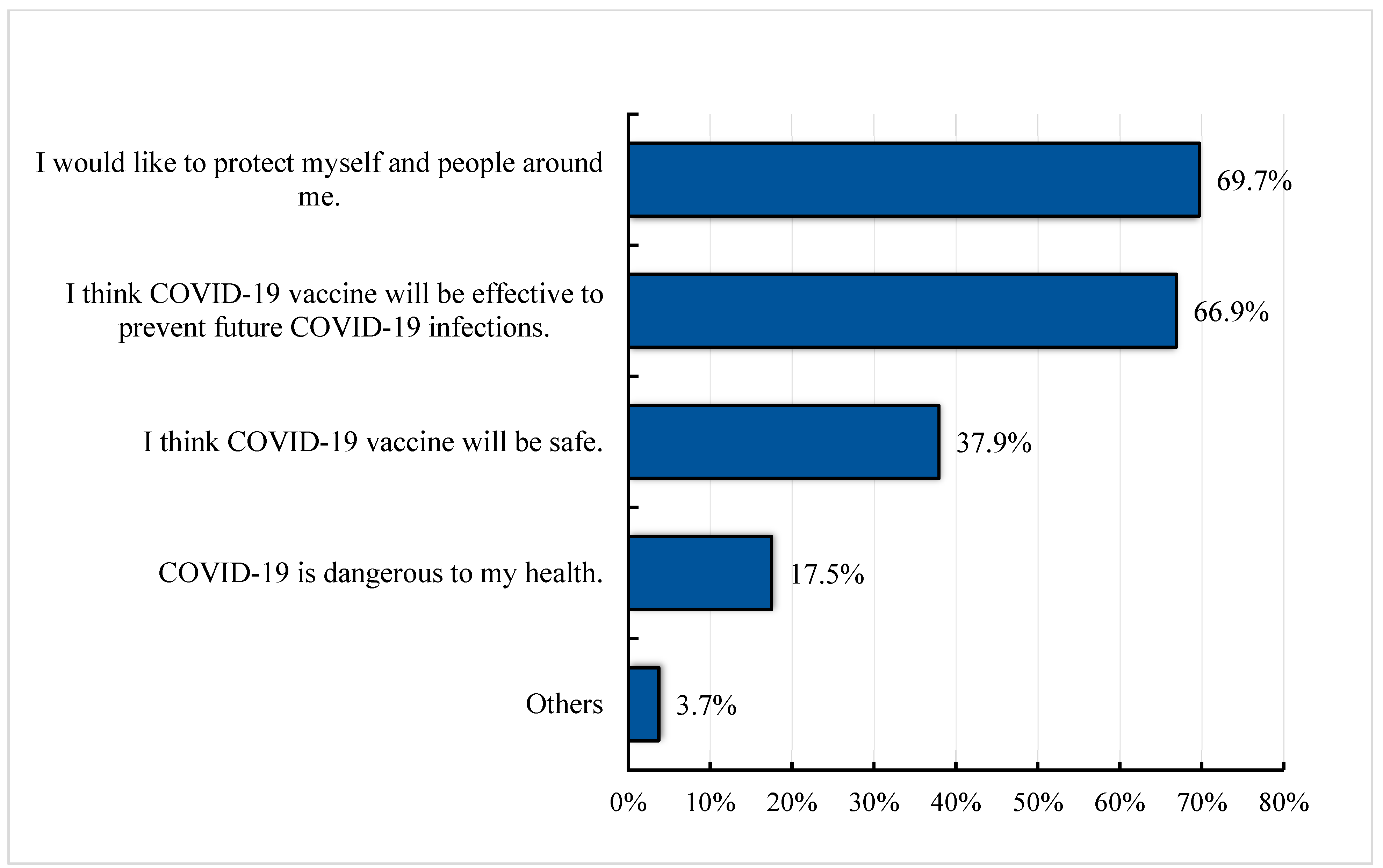

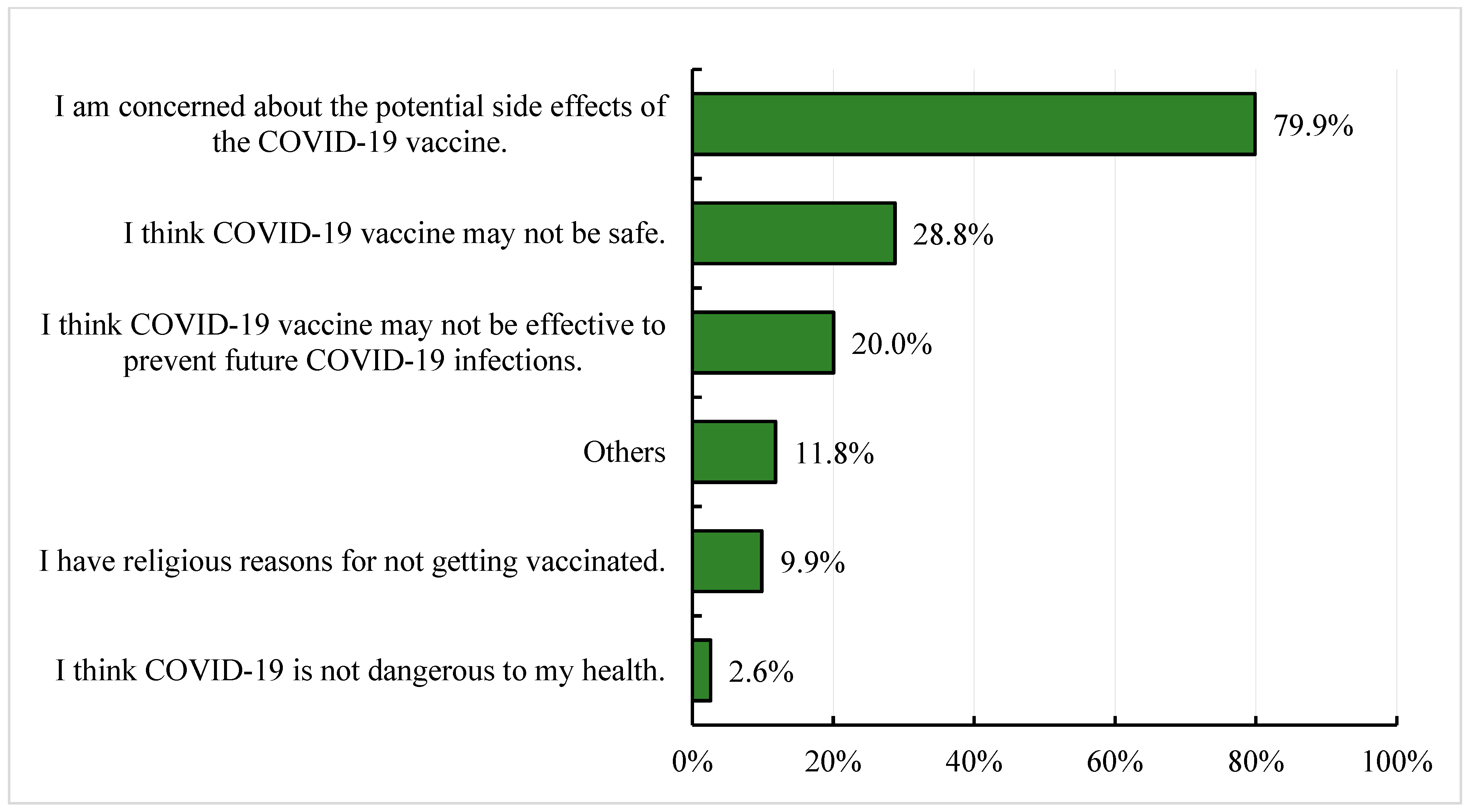

3.3. Reasons for Willingness and Lack of Willingness to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine

3.4. Awareness, Risk Perception, Impact of COVID-19 and Flu Vaccination History

3.5. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination Decision

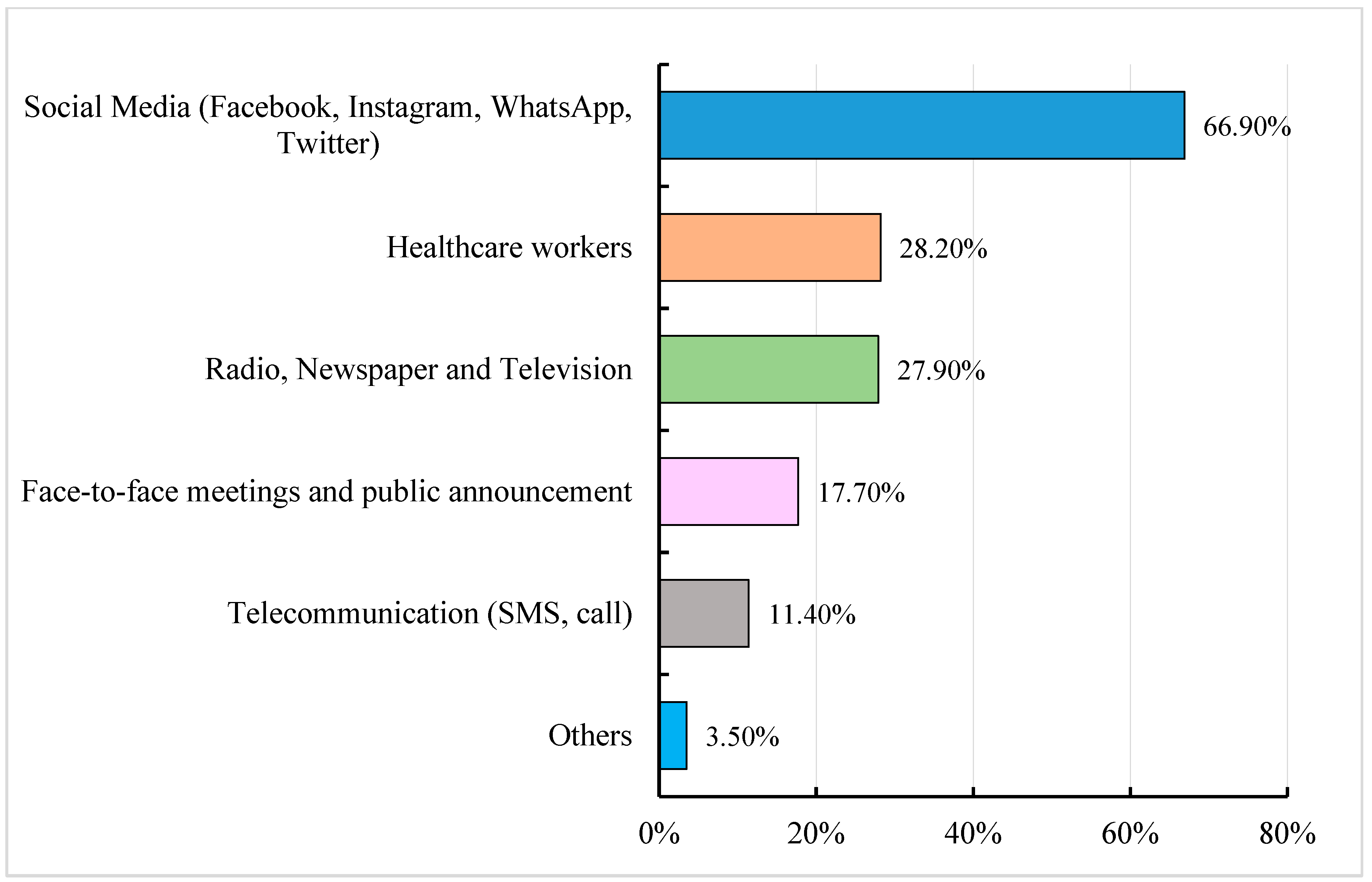

3.6. Source of Information on COVID-19, COVID-19 Vaccine and Vaccination and Trust in Information Sources

3.7. Factors Associated with Low Vaccine Acceptance in Aceh and Maluku

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, D.; Chang, X.; He, Y.; Tan, K.J.K. The determinants of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality across countries. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. New COVID-19 Cases Worldwide. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Machado, B.A.S.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Fonseca, L.M.D.S.; Pires, V.C.; Mascarenhas, L.A.B.; da Silva Andrade, L.P.C.; Moret, M.A.; Badaró, R. The Importance of Vaccination in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Brief Update Regarding the Use of Vaccines. Vaccines 2022, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Draft Landscape and Tracker of COVID-19 Candidate Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Dubé, E.; MacDonald, N.E. Chapter 26—Vaccine Acceptance: Barriers, Perceived Risks, Benefits, and Irrational Beliefs. In The Vaccine Book, 2nd ed.; Bloom, B.R., Lambert, P.-H., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 507–528. [Google Scholar]

- Determann, D.; Korfage, I.J.; Lambooij, M.S.; Bliemer, M.; Richardus, J.H.; Steyerberg, E.W.; de Bekker-Grob, E.W. Acceptance of Vaccinations in Pandemic Outbreaks: A Discrete Choice Experiment. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The health belief model: Explaining health behavior through expectancies. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; Glanz, K., Lewis, F.M., Rimer, B.K., Eds.; The Jossey-Bass Health Series; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Simas, C.F.A.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Eckersberger, E.; Smith, D.M.D.; Paterson, P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Cooper, L.Z.; Eskola, J.; Katz, S.L.; Ratzan, S. Addressing the vaccine confidence gap. Lancet 2011, 378, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indonesia Coronavirus: The Vaccination Drive Targeting Younger People. BBC News. 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55620356 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations—Statistics and Research. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Pratiwi, P.N.; Rakhmilla, L.E.; Suryadinat, H.; Sudjana, P. Factors Affecting Influenza Vaccine Acceptance as the Most Effective Prevention Among Nurses in West Java, Indonesia. Trends Appl. Sci. Res. 2020, 15, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudatsir, M.; Anwar, S.; Fajar, J.K.; Yufika, A.; Ferdian, M.N.; Salwiyadi, S.; Harapan, H. Willingness-to-pay for a hypothetical Ebola vaccine in Indonesia: A cross-sectional study in Aceh. F1000Res 2020, 8, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Sim, J.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Sevdalis, N.; Smith, L.E. COVID-19 vaccination acceptability in the UK at the start of the vaccination programme: A nationally representative cross-sectional survey (CoVAccS—Wave 2). Public Health 2022, 202, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Sabat, I.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; van Exel, J.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M.; Padhi, B.K. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A Web-Based National Survey. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.O.; Natto, H.A. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and trust among adults in Makkah, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2022, 97, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.C.; Wong, E.L.; Huang, J.; Cheung, A.W.; Law, K.; Chong, M.K.; Ng, R.W.; Lai, C.K.; Boon, S.S.; Lau, J.T.; et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: A population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qerem, W.A.; Jarab, A.S. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Its Associated Factors among a Middle Eastern Population. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuters. Indonesian Clerics Declare Sinovac’s COVID-19 Vaccine Halal. 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-indonesia-vaccine-idUSKBN29D16U (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Vo, T.Q.; et al. Willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 3074–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefriando, M. Indonesia Pledges Free COVID-19 Vaccines, with President First in Line. Reuters. 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-indonesia-vaccines-idUSKBN28Q102 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Reuters Staff. Sinopharm, Sinovac COVID-19 Vaccine Data Show Efficacy: WHO. Reuters. 2021. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-who-china-vaccines-idUSKBN2BN1K8 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Cohen, J. AstraZeneca Lowers Efficacy Claim for COVID-19 Vaccine, a Bit, after Board’s Rebuke. Science|AAAS. 2021. Available online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2021/03/astrazeneca-lowers-efficacy-claim-covid-19-vaccine-bit-after-boards-rebuke (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- AstraZeneca. AZD1222 US Phase III Primary Analysis Confirms Safety and Efficacy. 2021. Available online: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2021/azd1222-us-phase-iii-primary-analysis-confirms-safety-and-efficacy.html (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Olliaro, P.; Torreele, E.; Vaillant, M. COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and effectiveness—The elephant (not) in the room. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, E279–E280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 Vaccine: EMA Finds Possible Link to Very Rare Cases of Unusual Blood Clots with Low Platelets. 2021. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/astrazenecas-covid-19-vaccine-ema-finds-possible-link-very-rare-cases-unusual-blood-clots-low-blood (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Bhopal, S.; Nielsen, M. Vaccine hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries: Potential implications for the COVID-19 response. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J. Blocking information on COVID-19 can fuel the spread of misinformation. Nature 2020, 580, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Walker, J.L.; Paterson, P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: A multi-methods study in England. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7789–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Alias, H.; Danaee, M.; Wong, L.P. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ma, M.; Miao, Y.; Ye, B.; Li, Q.; Tarimo, C.S.; Wang, M.; Gu, J.; Wei, W.; Zhao, L.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance Among Chinese Population and its Implications for the Pandemic: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 796467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. COVID-19: Johnson and Johnson vaccine trial is paused because of unexplained illness in participant. BMJ 2020, 371, m3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Indonesia Smartphone Users. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/266729/smartphone-users-in-indonesia/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

| Socio-Demographic Variables | Frequency (n) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Province (University) | ||

| Jawa Barat (Universitas Padjadjaran) | 600 | 17.7 |

| Aceh (Universitas Syiah Kuala) | 689 | 20.3 |

| Nusa Tenggara Barat (Universitas Mataram) | 790 | 23.3 |

| Maluku (Universitas Pattimura) | 1310 | 38.7 |

| Student or Lecturer | ||

| Student | 2637 | 77.3 |

| Lecturer | 776 | 22.7 |

| Medical and Non-medical Faculty | ||

| Medical (Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Dentistry, Psychology, Veterinary Medicine) | 2078 | 61.0 |

| Non-medical (Other faculties) | 1326 | 39.0 |

| Duration of teaching or learning | ||

| ≤1 year | 667 | 20.0 |

| ≤2 years | 645 | 19.4 |

| ≤3 years | 542 | 16.3 |

| ≤4 years | 376 | 11.3 |

| ≤5 years | 264 | 7.9 |

| >5 years | 836 | 25.1 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 2493 | 72.8 |

| 26–35 | 296 | 8.6 |

| 36–45 | 290 | 8.5 |

| 46–55 | 197 | 5.7 |

| 56–65 | 144 | 4.2 |

| >65 | 6 | 0.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1096 | 32.0 |

| Female | 2330 | 68.0 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 2643 | 77.3 |

| Married | 776 | 22.7 |

| Religion | ||

| Islam | 2389 | 69.5 |

| Hinduism | 123 | 3.6 |

| Catholic | 63 | 1.8 |

| Christian | 847 | 24.7 |

| Buddhism | 6 | 0.2 |

| Kong hu chu | 3 | 0.1 |

| Others | 4 | 0.1 |

| Average monthly household expenditure (Indonesian Rupiah) | ||

| ˂1 million | 262 | 7.7 |

| 1–<5 million | 1168 | 34.5 |

| 5–<10 million | 636 | 18.8 |

| 10–<20 million | 218 | 6.4 |

| ≥20 million | 64 | 1.9 |

| Prefer not to say | 1041 | 30.7 |

| Type of health insurance you/your family have | ||

| National Health Insurance (BPJS) | 2644 | 77.4 |

| Personal/private insurance | 115 | 3.3 |

| Both insurance | 277 | 8.1 |

| No insurance | 382 | 11.2 |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine Yes vs. No and Not Sure n (%) | Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine Yes vs. No and Not Sure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | p-Value | OR (95 C.I.) | ||

| Province (University) (N = 3380) | ||||

| Jawa Barat (Universitas Padjadjaran) | 408 (68.1)/191 (31.9) | 0.99 | <0.001 ** | 2.70 (2.20–3.31) |

| Aceh (Universitas Syiah Kuala) | 268 (39.0)/419 (61.0) | −0.21 | 0.028 * | 0.81 (0.67–0.98) |

| Nusa Tenggara Barat (Universitas Mataram) | 443 (56.1)/346 (43.9) | 0.48 | <0.001 ** | 1.62 (1.36–1.94) |

| Maluku (Universitas Pattimura) | 576 (44.1)/729 (55.9) | Ref | ||

| Student/Lecturer (N = 3404) | ||||

| Student | 1321 (50.2)/1308 (49.8) | 0.003 | 0.97 | 1.03 (0.85–1.18) |

| Lecturer | 390 (50.3)/385 (49.7) | Ref | ||

| Faculty (N = 3396) | ||||

| Medical | 1217 (58.7)/857 (41.3) | 0.87 | <0.001 ** | 2.39 (2.08–2.76) |

| Non-medical | 492 (37.2)/830 (62.8) | Ref | ||

| Duration of teaching/learning (N = 3324) | ||||

| ≤1 year | 327 (49.2)/338 (50.8) | Ref | ||

| ≤2 years | 305 (47.4)/339 (52.6) | −0.07 | 0.51 | 0.93 (0.75–1.15) |

| ≤3 years | 243 (44.9)/298 (55.1) | −0.17 | 0.14 | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) |

| ≤4 years | 201 (53.6)/174 (46.4) | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.19 (0.93–1.54) |

| ≤5 years | 156 (59.1)/108 (40.9) | 0.40 | 0.006 * | 1.49 (1.12–1.99) |

| >5 years | 443 (53.1)/392 (46.9) | 0.15 | 0.13 | 1.17 (0.95–1.43) |

| Age (N = 3419) | ||||

| 18–25 | 1251 (50.3)/1236 (49.7) | 0.01 | 0.99 | 1.01 (0.20–5.02) |

| 26–35 | 154 (52)/142 (48) | 0.08 | 0.92 | 1.08 (0.21–5.46) |

| 36–45 | 137 (47.2)/153 (52.8) | −0.11 | 0.89 | 0.89 (0.18–4.51) |

| 46–55 | 104 (53.1)/92 (46.9) | 0.12 | 0.88 | 1.13 (0.22–5.74) |

| 56–65 | 75 (52.1)/69 (47.9) | 0.08 | 0.92 | 1.09 (0.21–5.57) |

| >65 | 3 (50)/3 (50) | Ref | ||

| Gender (N=3419) | ||||

| Male | 588 (53.6)/508 (46.4) | 0.19 | 0.008 * | 1.21 (1.05–1.40) |

| Female | 1134 (48.8)/1189 (51.2) | Ref | ||

| Marital status (N = 3412) | ||||

| Single | 1333 (50.5)/1305 (49.5) | Ref | ||

| Married | 385 (49.7)/389 (50.3) | 0.03 | 0.70 | 1.03 (0.88–1.21) |

| Religion (N = 3428) | ||||

| Islam | 1184 (49.7)/1200 (50.3) | Ref | ||

| Hinduism | 96 (78)/27 (22) | 1.282 | <0.001 ** | 3.60 (2.33–5.56) |

| Christianity | 402 (47.6)/443 (52.4) | −0.08 | 0.30 | 0.92 (0.79–1.08) |

| Other | 41 (53.9)/35 (46.1) | 0.17 | 0.46 | 1.19 (0.75–1.88) |

| Monthly household expenditure (N = 3382) | ||||

| Low | 105 (40.2)/156 (59.8) | Ref | ||

| Medium | 943 (52.3)/860 (47.7) | 0.49 | <0.001 ** | 1.63 (1.25–2.12) |

| High | 176 (62.6)/105 (37.4) | 0.91 | <0.001 ** | 2.49 (1.76–3.52) |

| Prefer not to say | 479 (46.2)/558 (53.8) | 0.24 | 0.08 | 1.27 (0.97–1.68) |

| Type of health insurance (N = 3411) | ||||

| National health insurance | 1314 (49.8)/1323 (50.2) | 0.29 | 0.009 * | 1.33 (1.07–1.66) |

| Private health insurance | 67 (58.3)/48 (41.7) | 0.63 | 0.004 ** | 1.87 (1.23–2.86) |

| Both insurance | 174 (62.8)/103 (37.2) | 0.82 | <0.001 ** | 2.27 (1.65–3.12) |

| No insurance | 163 (42.7)/219 (57.3) | Ref | ||

| Characteristics | Frequency | Willingness to Be Vaccinated | Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine: Yes vs. No and Not Sure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No and Not Sure n (%) | B | p-Value | aOR (95 C.I.) | ||

| Associated with health sector during learning or teaching activities (N = 3407) | ||||||

| Yes | 1852 | 1039 (56.1) | 813 (43.9) | 0.36 | <0.001 ** | 1.43 (1.24–1.66) |

| No | 1555 | 676 (43.5) | 879 (56.5) | Ref | ||

| Awareness about COVID-19 cases in Indonesia (N = 3426) | ||||||

| Yes | 3411 | 1721 (50.5) | 1690 (49.5) | 1.08 | 0.17 | 2.96 (0.62–13.97) |

| No | 15 | 2 (13.3) | 13 (86.7) | Ref | ||

| Affected by COVID-19_Physically (N = 3353) | ||||||

| Yes | 1983 | 1057 (53.3) | 926 (46.7) | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.15 (0.98–1.35) |

| No | 1370 | 637 (46.5) | 733 (53.5) | Ref | ||

| Affected by COVID-19_Mentally (N = 3374) | ||||||

| Yes | 2352 | 1246 (53) | 1106 (47) | 0.10 | 0.25 | 1.11 (0.93–1.32) |

| No | 1022 | 462 (45.2) | 560 (54.8) | Ref | ||

| Affected by COVID-19_Socially (N = 3390) | ||||||

| Yes | 3135 | 1594 (50.8) | 1541 (49.2) | 0.03 | 0.85 | 1.03 (0.77–1.38) |

| No | 255 | 119 (46.7) | 136 (53.3) | Ref | ||

| Affected by COVID-19_Economically (N = 3381) | ||||||

| Yes | 2608 | 1262 (48.4) | 1346 (51.6) | −0.33 | <0.001 ** | 0.72 (0.60–0.86) |

| No | 773 | 437 (56.5) | 336 (43.5) | Ref | ||

| Infected with Coronavirus (N = 3418) | ||||||

| Yes | 128 | 68 (53.1) | 60 (46.9) | −0.29 | 0.14 | 0.74 (0.50–1.11) |

| No | 3290 | 1651 (50.2) | 1639 (49.8) | Ref | ||

| Knows family members infected with Coronavirus (N = 3331) | ||||||

| Yes | 737 | 424 (57.5) | 313 (42.5) | 0.099 | 0.31 | 1.10 (0.91–1.34) |

| No | 2594 | 1255 (48.4) | 1339 (51.6) | Ref | ||

| Knows colleagues infected with coronavirus (N = 3313) | ||||||

| Yes | 1076 | 598 (55.6) | 478 (44.4) | −0.24 | 0.013 * | 0.79 (0.65–0.95) |

| No | 2237 | 1072 (47.9) | 1165 (52.1) | Ref | ||

| Knows friends infected with coronavirus (N = 3344) | ||||||

| Yes | 1538 | 909 (59.1) | 629 (40.9) | 0.44 | <0.001 ** | 1.56 (1.30–1.86) |

| No | 1806 | 784 (43.4) | 1022 (56.6) | Ref | ||

| Risk of contracting COVID-19 (N = 3415) | ||||||

| Yes | 2361 | 1340 (56.8) | 1021 (43.2) | 0.60 | <0.001 ** | 1.83 (1.53–2.18) |

| No | 1054 | 378 (35.9) | 676 (64.1) | Ref | ||

| Received influenza vaccine in the last 5 years (N = 3411) | ||||||

| Yes | 263 | 163 (62) | 100 (38) | 0.34 | 0.018 * | 1.41 (1.06–1.86) |

| No | 3148 | 1556 (49.4) | 1592 (50.6) | Ref | ||

| Awareness of Phase III COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial in Indonesia (N = 3419) | ||||||

| Yes | 3071 | 1589 (51.7) | 1482 (48.3) | 0.46 | <0.001 ** | 1.59 (1.24–2.03) |

| No | 348 | 131 (37.6) | 217 (62.4) | Ref | ||

| Characteristics | Frequency n (%) | Willingness to Be Vaccinated | Intent to Be Vaccinated: Yes vs. No and Not Sure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No and Not Sure, n (%) | B | p-Value | aOR (95 C.I.) | ||

| Vaccine Efficacy (N = 3086) | ||||||

| I would take COVID-19 vaccine if it is ≥80% effective. | 2360 (76.4) | 1223 (51.8) | 1137 (48.2) | 3.36 | 0.001 ** | 28.89 (3.96–210.96) |

| I would like to take COVID-19 vaccine if it is even 50–80% effective. | 389 (12.6) | 281 (72.2) | 108 (27.8) | 4.21 | <0.001 ** | 67.66 (9.16–499.85) |

| I would take COVID-19 vaccine irrespective of the vaccine efficacy data. | 178 (5.8) | 93 (52.2) | 85 (47.8) | 3.66 | <0.001 ** | 39.06 (5.24–291.42) |

| I have not decided yet about COVID-19 vaccination | 35 (1.1) | 1 (2.9) | 34 (97.1) | 17.56 | 0.99 | - |

| Others | 59 (1.9) | 9 (15.3) | 50 (84.7) | 2.21 | 0.041 * | 9.09 (1.09–75.59) |

| I am hesitant about COVID-19 vaccination. | 65 (2.1) | 1 (1.5) | 64 (98.5) | Ref | ||

| Number of doses (N = 3040) | ||||||

| I would consider number of doses as one of the criteria to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | 2315 (76.1) | 1315 (56.8) | 1000 (43.2) | 0.34 | 0.007 * | 1.41 (1.10–1.80) |

| I would not consider number of doses as one of the criteria to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | 725 (23.9) | 280 (38.6) | 445 (61.4) | Ref | ||

| Mode of administration (N = 3004) | ||||||

| I would consider mode of administration as one of the criteria to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | 2103 (70) | 1198 (57) | 905 (43) | 0.22 | 0.051 | 1.25 (0.99–1.57) |

| I would not consider mode of administration as one of the criteria to receive COVID-19 vaccine. | 901 (30) | 385 (42.7) | 516 (57.3) | Ref | ||

| Willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccine (Estimated price IDR 200,000–IDR 500,000 (USD13.19–USD32.97)) (N = 3092) | ||||||

| Full price | 499 (16.1) | 388 (77.8) | 111 (22.2) | 1.51 | <0.001 ** | 4.53 (3.50–5.84) |

| Only partially, rest must be subsidized by the government. | 597 (19.3) | 394 (66) | 203 (34) | 0.89 | <0.001 ** | 2.45 (1.97–3.06) |

| I cannot afford the vaccine. | 264 (8.5) | 90 (34.1) | 174 (65.9) | −0.28 | 0.069 | 0.76 (0.56–1.02) |

| Depends on the actual vaccine price. | 555 (18) | 289 (52.1) | 266 (47.9) | 0.35 | 0.002 ** | 1.42 (1.14–1.77) |

| Others | 126 (4.1) | 27 (21.4) | 99 (78.6) | −0.43 | 0.091 | 0.65 (0.39–1.07) |

| The government must provide the vaccine for free. | 1051 (34) | 423 (40.2) | 628 (59.8) | Ref | ||

| Statements | Intent to Be Vaccinated Yes vs. No and Not Sure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | p-Value | aOR (95 C.I.) | |

| COVID-19 vaccine is the most effective tool to prevent COVID-19. | 0.86 | <0.001 ** | 2.37 (1.57–3.59) |

| I decided to be vaccinated because of my family advice. | 0.06 | 0.74 | 1.06 (0.74–1.51) |

| I decided to be vaccinated because my university suggested so. | 0.99 | <0.001 ** | 2.70 (1.89–3.86) |

| I do not like injections in general. | −0.34 | 0.007 * | 0.71 (0.56–0.91) |

| I am worried there will be side effects after COVID-19 vaccination. | −0.90 | 0.001 ** | 0.41 (0.23–0.70) |

| I might still get COVID-19 even when I am vaccinated with COVID-19 vaccine. | 0.24 | 0.12 | 1.27 (0.94–1.71) |

| COVID-19 vaccine will be expensive when available. | −0.28 | 0.04 * | 0.76 (0.58–0.99) |

| I believe COVID-19 disease prevention naturally is better than to be vaccinated. | −0.78 | <0.001 ** | 0.46 (0.34–0.60) |

| COVID-19 is dangerous to my health. | 0.59 | 0.052 | 1.81 (0.99–3.28) |

| The COVID-19 vaccine is the only solution to end pandemic in the shortest time possible. | −0.71 | <0.001 ** | 0.49 (0.35–0.69) |

| The COVID-19 vaccine will be safe and effective. | 3.22 | <0.001 ** | 25.11 (12.87–49.15) |

| My government is handling COVID-19 crisis very well. | −0.38 | 0.024 * | 0.68 (0.49–0.95) |

| My government provides transparent and up-to-date information on COVID-19 vaccine development and its introduction. | 0.04 | 0.82 | 1.04 (0.73–1.49) |

| I trust the government on COVID-19 vaccine planning and introduction. | 0.94 | <0.001 ** | 2.55 (1.67–3.89) |

| I value the importance of vaccine and vaccination more now after the onset of COVID-19 pandemic. | 0.17 | 0.57 | 1.18 (0.66–2.12) |

| I valued the importance of vaccine and vaccination before the onset of COVID-19 pandemic as well. | 0.62 | 0.08 | 1.85 (0.93–3.68) |

| Information Sources | Mean Score |

|---|---|

| The rank of main sources of information | |

| Social Media (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram and Twitter) | 2.30 |

| Radio, Newspapers and Television | 3.40 |

| Ministry of Health and COVID-19 Task force website | 3.59 |

| Doctors | 4.28 |

| Family and friends | 4.32 |

| Community announcement by the government | 4.86 |

| University website | 5.26 |

| The rank of sources participants trusts the most | |

| Ministry of Health and COVID-19 Task force website | 2.67 |

| Doctors | 2.96 |

| Radio, Newspapers and Television | 3.97 |

| Social Media (Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram and Twitter) | 4.29 |

| Community announcement by the government | 4.40 |

| University website | 4.53 |

| Family and friends | 5.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khatiwada, M.; Nugraha, R.R.; Harapan, H.; Dochez, C.; Mutyara, K.; Rahayuwati, L.; Syukri, M.; Wardoyo, E.H.; Suryani, D.; Que, B.J.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among University Students and Lecturers in Different Provinces of Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2023, 11, 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030683

Khatiwada M, Nugraha RR, Harapan H, Dochez C, Mutyara K, Rahayuwati L, Syukri M, Wardoyo EH, Suryani D, Que BJ, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among University Students and Lecturers in Different Provinces of Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2023; 11(3):683. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030683

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhatiwada, Madan, Ryan Rachmad Nugraha, Harapan Harapan, Carine Dochez, Kuswandewi Mutyara, Laili Rahayuwati, Maimun Syukri, Eustachius Hagni Wardoyo, Dewi Suryani, Bertha J. Que, and et al. 2023. "COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among University Students and Lecturers in Different Provinces of Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Vaccines 11, no. 3: 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030683

APA StyleKhatiwada, M., Nugraha, R. R., Harapan, H., Dochez, C., Mutyara, K., Rahayuwati, L., Syukri, M., Wardoyo, E. H., Suryani, D., Que, B. J., & Kartasasmita, C. (2023). COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among University Students and Lecturers in Different Provinces of Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines, 11(3), 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030683