Abstract

Background: Τhe study aims to identify factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and to investigate knowledge and perceptions of Primary Health Care Centers (PHCC) personnel, who acted as pioneers in the national COVID-19 vaccination strategy. Methods and Materials: A nationwide cross-sectional survey was conducted by distributing an online anonymous questionnaire comprising 25 questions during the first semester of 2021. Results: Approximately 85.3% of the 1136 respondents (response rate 28.4%) were vaccinated or intended to be. The acceptance of seasonal flu vaccine (aOR: 3.29, 95%CI: 2.08–5.20), correct COVID-19 vaccine knowledge (aOR: 8.37, 95%CI: 4.81–14.59) and lack of concern regarding vaccine novelty (aOR: 6.18, 95%CI: 3.91–9.77) were positively correlated with vaccine acceptance. Vaccinated respondents were more likely to be physicians (aOR: 2.29, 95%CI: 1.03–5.09) or administrative staff (aOR: 2.65, 95%CI: 1.18–5.97) compared to nursing stuff. Reasons for vaccine hesitancy included inadequate information (37.8%) and vaccine safety (31.9%). Vaccine acceptance was strongly correlated (Spearman’s correlation coefficient r = 0.991, p < 0.001) between PHCC personnel and the general population of each health district. Conclusions: COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among PHCC personnel in Greece was comparably high, but specific groups (nurses) were hesitant. As the survey’s target population could serve as a role model for the community, efforts should be made to improve COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.

Keywords:

COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; vaccine; vaccination; health care workers; acceptance; hesitancy; vaccine safety 1. Introduction

After the declaration of a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), the World Health Organization (WHO) characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic in March 2020 [1]. By April 2021 and following evaluation by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), four vaccines were authorized for use in the European Union (EU) under conditional marketing authorization [2], in an effort to confront the devastating impacts of the pandemic. Currently, six WHO authorized vaccines are available worldwide [3]. Up until December 2021, more than 270,500,000 cases of COVID-19 were reported globally resulting in over 5,000,000 deaths, while more than 8 billion doses of authorized vaccines have been distributed [4]. In the EU alone, almost 27 million COVID-19 cases and more than 300,000 deaths were reported by December 2021, while over 300,000,000 adults received at least one vaccine dose [4]. Meanwhile, data from the Hellenic National Public Health Organization (NPHO) revealed that in Greece a total of 1,017,445 COVID-19 cases were reported by 15 December 2021, with 19,553 related deaths [5]. The one-dose vaccine coverage for adults in the country reached 69.1% as of 15 December 2021 [6].

WHO has defined vaccine hesitancy as a behavior related to a variety of factors, including confidence, complacency (perceived risks of vaccine-preventable diseases are low) and convenience (access issues) [7]. Previous experience related to the administration of new vaccines, such as the influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccine, demonstrated that vaccination hesitancy prevented the achievement of efficient vaccine coverage even among health care personnel, despite the authorities’ recommendations [8,9]. Moreover, WHO highlights that health care sector personnel can play an important role in the successful implementation of a vaccination policy, as they can contribute to vaccination promotion and act as role models for the community [3]. Recent studies revealed that doctors’ advice for COVID-19 vaccination counts in favor of vaccine acceptance [10,11,12]. In Greece, the current COVID-19 vaccination project involves all personnel working in Primary Health Care Centers (PHCC) [13]. PHCC are publicly funded and consist of Rural Health Centers (RHC) and Urban Health Units (UHU). PHCC staff include Health Care Workers (HCW), such as physicians, nurses and other health care professionals (social and welfare, health promotion, midwives, ambulance personnel, etc.), and Administrative Officers (AO). PHCC responsibilities involve medical care, health promotion, vaccinations and health consultations (breast feeding, mental health, actions in schools and community centers), all of which build a strong bond between PHCC professionals and civilians.

Although the vaccination coverage of Greek health care personnel is continuously monitored by the NPHO and communicated to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [6], information about subgroups of HCWs and AOs is not formally available. Surveys conducted among the general population regarding attitudes toward future vaccination have shown that, early in the pandemic (April–May 2020), 18.9% of respondents declared they were against vaccination, while 81.1% declared that they may consider or will be vaccinated [14]. Since PHCC personnel play an essential role in Greece for the provision of information and vaccine administration, data related that their COVID-19 vaccine acceptance may contribute to the assessment and improvement of the Greek vaccine campaign, by focusing on the above target group if necessary. In late July 2021, the Greek government introduced legislation on the mandatory COVID-19 vaccination of personnel of health care facilities in both the public and private sectors. However, up until April 2022, the vaccination coverage of HCW, according to ECDC COVID-19 vaccines tracker, reached 90.7%, despite the legislation requirement for mandatory vaccination [15]. Approximately 9% of HCW preferred to abandon their job or to have unpaid leave for several months, instead of getting the COVID-19 vaccine. Data related to COVID-19 vaccine acceptance/hesitancy is important, in order to understand the profile of hesitant professionals and adapting vaccination policies accordingly. The aim of our study is to: (a) estimate both the intention and uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among PHCC personnel, (b) identify factors related to their decision to get vaccinated, (c) investigate perceptions and behavioral aspects of PHCC personnel in relation to vaccination and (d) identify aspects that can facilitate PHCC personnel to be role models for the general population.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional online questionnaire-based survey was conducted between February and June 2021 when authorized COVID-19 vaccines were available in Greece, in order to assess the knowledge, attitudes and practices of PHCC personnel (HCWs and AO), as well as factors related to COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. A sample size of 916 was calculated using a Raosoft Digital Sample Size Calculator [16], in which 3% was used as a margin of error, 95% as the confidence interval (CI), 50% as the expected frequency and 6456 as the population size [17]. Due to the online distribution format, the estimated response rate was approximately 22%, and a sample of 4000 was calculated [18]. A geographically stratified sampling plan based on Greek health districts was applied to produce a representative sample of 125 PHCC, located both in mainland and Greek islands.

An anonymous online questionnaire consisting of 25 questions was designed after considering guidelines published by WHO, advice issued by the Hellenic National Public Health Organization (NPHO) and the Ministry of Health, as well as relevant studies conducted in Greece [9,14,18,19,20]. The study was supervised by an expert team comprising an epidemiologist, an occupational health professional and a public health specialist who were responsible for the face and content validation of the questionnaire. The pilot testing of the first draft questionnaire was conducted to evaluate the time required for its completion, to appraise the clarity of the questions addressed to professionals from various backgrounds and to test the online tool functionality. A total of 20 PHCC professionals, including HCWs and AOs, completed the draft questionnaire, which was modified appropriately to produce the final version of the survey. Questionnaires completed during pilot testing were excluded from the final analysis. Internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire was assessed by estimating an Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.70, which was considered as acceptable [21].

The questionnaire included questions about knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) regarding vaccinations in general as well as the COVID-19 vaccination specifically (S1-Supplementary Materials). The time required for completion of the questionnaire was approximately 15 min. The collection, entry, analysis and storage of survey data complied with the anonymity, privacy and confidentiality regulations of the national legislation and rules of the University of Thessaly, Greece. In order to identify whether COVID-19-vaccination-hesitant professionals were less acceptant of vaccination generally, the survey questionnaire included questions related to knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding general vaccination (questions 14–17) and questions related to COVID-19 vaccines specifically (question 22).

The researchers contacted selected PHCC to distribute the questionnaire, which was forwarded through email to PHCC personnel. The email contained an invitation letter detailing the survey protocol, issues regarding confidentiality and the researchers’ contact information. Moreover, the cover letter provided a link to the online questionnaire and emphasized voluntary participation. Electronic and hard copies of the cover letter and questionnaire were distributed, with reminders sent to increase the response rate [18,22]. Participants had the option of completing either the electronic or hard copy after written consent was obtained. Online answers were stored automatically, while the hard copy questionnaires were sent by courier to researchers. Data were entered in the database when needed from hard copies by trained staff. PHCC emails and contact details were obtained from the Regional Health Authorities’ websites.

From 11 February (approximately one month after the initiation of COVID-19 vaccination) to 30 June 2021, the structured and anonymous questionnaire was distributed to PHCC, with both HCWs and AOs invited to participate. The questionnaire (S1) included 11 questions related to demographics and 14 questions for the assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning immunization generally and for COVID-19 specifically. The general section of the questionnaire included questions about demographics, education, workplace and length of work experience. Part A included generic questions related to vaccination, while part B referred specifically to COVID-19 and vaccination. In part A, the first two questions referred to respondents and their family vulnerability, according to their medical history (answer: Yes/No). This was followed by questions about knowledge and attitudes/perceptions. Each category had three sub-questions (three for knowledge and three for attitudes). Answers were given on a 5-level item scale (“completely agree”, “agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “disagree” and “completely disagree”). The last two questions in part A applied to vaccination practices, either to respondents’ children if any, or to themselves regarding the seasonal influenza vaccine. Those who responded negatively about seasonal influenza vaccination were asked to explain their response through a semi-closed question. In part B, respondents were asked about any contact they had with a COVID-19 patient during either social or professional activities (Yes/No). A question regarding self-evaluation of their COVID-19 knowledge followed (four-level item: Non-existent/Insufficient/Satisfactory/Excellent) and another question related to their source of information. COVID-19 vaccine knowledge was evaluated through three questions, which were answered using a 5-level item scale (“completely agree”, “agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “disagree” and “completely disagree”). COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was measured through the question “Have you or will you be vaccinated with one of the vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19, which has been approved by the National Pharmaceutical Organization?”. Participants who responded negatively were requested to specify the reason (semi-closed question). Finally, all participants were asked if the short period for COVID-19 vaccine development (vaccine novelty) concerned them and if they believed in mandatory vaccination for health care professionals (Yes/No).

2.2. Ethical Statement

The questionnaire was approved by the Ministry of Health and the Regional Health Authorities. Ethical approval from the scientific committee of the University of Thessaly (protocol number 49/13 January 2021) was obtained. All participants provided written consent before completing the questionnaire.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The relationship between the main outcome measure (acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine) and participants’ characteristics (baseline characteristics, perception and knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine) were assessed using either chi-square analysis or Student’s t-test. A Student’s t-test was performed for continuous data since there was no deviation from normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk normality test) and violation of the assumption of homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test). In univariate analysis, the percentage of those vaccinated and the proportional ratio (PR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented. The direction of the association was analyzed using a bivariate logistic regression analysis with a 95%CI. The selection of variables for the bivariate logistic regression model were based on factors previously reported in the literature and found to be significant in the chi-square analysis or Student’s t-test. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to measure the strength and direction of association between the percentage of vaccinated PHCC personnel and percentage of vaccinated adults (at least one dose) in each health district. Population data for each health district/prefecture were obtained from the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT)and the National Vaccination Registry [23,24]. All tests were 2-sided and a p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Certain survey questions (questions 14, 15, 22 and 24) were rated on a 5-point scale as follows: “completely disagree”, “disagree”, “neither agree nor disagree, agree” and “completely agree”. The responses “completely disagree”, “disagree” or “neither agree nor disagree” were considered to indicate disagreement, while responses of “completely agree” or “agree” were taken as agreement. Survey questions 14, 15 and 22 each consisted of three sub-questions. Correct answers to all three sub-questions were considered as a correct answer, whereas answering at least one of the three sub-questions incorrectly was considered as an incorrect answer.

Regarding sources of information, through univariate analysis, two groups were created. The first group included formal sources of information (medical articles in journals, committee for infectious diseases at the health facility, websites of the NPHO and the Hellenic Ministry of Health), while the other group included informal information sources (television, social media channels, newspapers and general interest publications/journals/websites). Each source of information counted a frequency score up to 4 depending on the participant’s answer (1 = always, 2 = often, 3 = rarely, 4 = never). The analysis was based on the relevant frequency score in order to categorize respondents to each group.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Demographics

A total of 4000 questionnaires were disseminated to PHCC personnel, with 1136 HCWs and AOs having responded (response rate: 28.4%). The majority of participants were female (69.8%), married (69.1%) and the average age was 43.8 years; most participants possessed a bachelor’s or a master’s degree (63.4%). Participants’ occupations covered the entire spectrum of primary care, including nursing staff (25.8%), physicians (46.1%) and other health care workers (social/welfare workers, midwives, health promotion specialists (10.1%); other health care workers (laboratory staff, radiologists and ambulance crew) (9.2%); and administrative officers (8.8%)). The vast majority of the respondents worked in a RHC (86.5%), and the median years of practice was 15 (IQR = 10). The percentage of vulnerable participants due to their medical history and participants living with vulnerable people were 17.2% and 27.9%, respectively. Questions 14 and 15, which were related to generic knowledge and perceptions towards vaccination, were answered correctly by 70.6% and 45.7% of respondents, respectively. More than half of respondents (61.2%) declared that they were parents, and of these respondents 98.1% adhered to the National Vaccination Program. The majority of respondents declared that they were vaccinated regularly for seasonal influenza (79%). Most participants knew individuals who experienced COVID-19 infection (85.1%), while 75.6% of respondents were contacts of a COVID-19 patient in the workplace. Most respondents rated the information they obtained related to COVID-19 as “excellent” of “satisfactory” (15.3% and 62%, respectively), while 1.1% believed that they were “uninformed”. More than half of the participants (57.9%) answered questions related to knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines correctly. From 1136 participants, 969 (85.3%) declared that they were fully vaccinated or intended to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Finally, 68.9% of respondents were concerned about the novelty of the vaccine and its rapid development, while 53.1% agreed with a vaccine mandate for health care professionals.

3.2. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, expressed with proportional ratio (PR) in univariate analysis (Total number of respodents 1136).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of the generic knowledge and attitudes towards vaccines and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (Section A) (N = 1136).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of the knowledge and attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (Section B) (N = 1136).

Factors that were positively associated with vaccine acceptance emerged through univariate analysis and included a higher education level (PR: 1.26, 95%CI: 1.13–1.41), being a physician (PR: 1.22, 95%CI: 1.14–1.31), working in a specific health district (PR: 1.19, 95%CI: 1.14–1.25), a higher score on vaccination knowledge (Q14) and perceptions (Q15) (PR: 1.24 95%CI: 1.16–1.33 and PR: 1.24, 95%CI: 1.18–1.30, respectively), accepting influenza vaccination (PR: 1.44 95%CI, 1.30–1.58) and adhering to the National Child Vaccination Program as a parent (PR: 1.71, 95%CI: 0.97–3.02).

Table 4 describes the results from the multivariate analysis.

Table 4.

Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, expressed with adjusted odds ratio (aOR), in a multivariable analysis.

A statistically significant association was found among COVID-19 vaccination and specific occupations, health district of employment, and being vaccinated for seasonal influenza (aOR: 3.29, 95%CI: 2.08–5.20). Moreover, correctly answering questions related to knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines (aOR: 8.37 95%CI: 4.81–14.59) and fewer concerns about the novelty of vaccines and their rapid development (aOR: 6.18, 95%CI: 3.91–9.77) were both positively associated with vaccine acceptance.

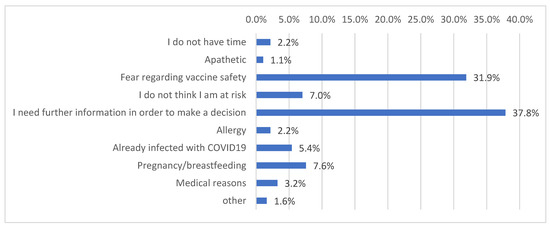

Figure 1 demonstrates the reasons for COVID-19 vaccination refusal among study participants.

Figure 1.

Distribution of reasons for COVID-19 vaccination refusal.

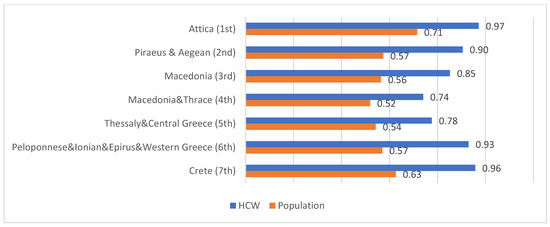

According to data from the National Vaccination Registry, at the time of our survey, the countrywide proportion of COVID-19 vaccination in the general adult population was approximately 42% [24]. A strong positive correlation was identified between the percentage of vaccinated PHCC personnel and vaccinated adults in the general population (at least one dose) in each health district (Spearman’s correlation coefficient ρ = 0.991, p < 0.001) (Figure 2 and Table 5).

Figure 2.

COVID-19 vaccination percentages of PHCC personnel and general population in each health district.

Table 5.

Correlation between PHCC personnel COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and adult population vaccination coverage against COVID-19.

Further analysis was conducted to investigate the association between knowledge/perception questions and sources of information, demographic characteristics and determinants of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance. The results of the aforementioned analysis are presented in Tables S6 and S7 of the Supplementary Material (S2 Table S6 and S3 Table S7). Regarding the association between information sources and COVID-19 vaccination acceptance, formal sources of information about COVID-19 vaccination were positively associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: articles in scientific medical journals (PR: 1.15, 95%CI: 1.08–1.23), infection control committee at a health facility (PR: 1.09, 95%CI: 1.04–1.15), NPHO website (PR: 1.19, 95%CI: 1.10–1.29) and the Hellenic Ministry of Health website (PR: 1.11, 95%CI: 1.05–1.18) (Supplementary materials S2 Table S6.)

Variables associated with general vaccination knowledge (Q14) and positive vaccination perceptions (Q15) as well as COVID-19 vaccine knowledge (Q22) are shown in Table S7. Generally, the top score to the aforementioned questions was positively associate with a higher educational level (PR: 1.98, 95%CI: 1.60–2.46, PR: 2.83, 95%CI: 1.96–4.09, PR: 2.52, 95%CI: 1.87–3.38), being a physician or health promotion specialist (PR: 1.49, 95%CI: 1.37–1.63, PR: 2.40, 95%CI: 2.04–2.82, PR: 1.61, 95%CI: 1.44–1.81), being vaccinated against seasonal influenza (PR: 1.26, 95%CI: 1.16–1.37, PR: 1.31, 95%CI: 1.23–1.39, PR: 1.24, 95%CI: 1.16–1.33), having less concerns about COVID-19 vaccine novelty (PR: 1.3, 95%CI: 1.17–1.44, PR: 1.45, 95%CI: 1.34–1.57, PR: 1.37, 95%CI: 1.25–1.49) and believing in the COVID-19 vaccine mandate (PR: 1.3, 95%CI: 1.17–1.44, PR: 1.37, CI: 1.23–1.53, PR: 1.34, 95%CI: 1.19–1.51).

3.3. Internal Consistency Reliability

The internal consistency of the questionnaire was established by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The reliability coefficient was calculated at 0.732, suggesting an acceptable internal consistency.

4. Discussion

Our study provided an appraisal of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among PHCC personnel in Greece (HCWs and AOs) and of factors related to the decision making of health care personnel during the first months in which they were able to access COVID-19 vaccines. During the study period, the vaccination of both HCW and the general public was optional. The target group of our study was expected to play a major role in promoting COVID-19 vaccination to the general population and data concerning their intention to get vaccinated and factors related to their decision were important to be investigated when designing and implementing the vaccination strategy. Vaccination monitoring among health care personnel has shown that approximately 9% of HCW refused the COVID-19 vaccination as of April 2022 [15]. Our study reported an 85.3% vaccine acceptance during the study period (from February to June 2021), while data available from the ECDC COVID-19 vaccines tracker reported that the total vaccination coverage among HCW in Greece is currently 90.7%, which demonstrates an increase of approximately 5%, after the introduction of legislation for the mandatory COVID-19 vaccination of HCW since late July 2021 [15]. Unfortunately, no follow up study was conducted by our team. An ongoing international survey coordinated by WHO is expected to give more insights on changes in vaccination coverage over time and identify factors related to vaccine hesitancy [25].

Vaccine acceptance in our study (85.3%) was found to be higher compared to other studies conducted in Greece. In particular, three studies conducted before the availability of an effective vaccine showed vaccine acceptance to be 51.1% [26], 78.5% [19] and 43% [20]. However, one study conducted after the release of COVID-19 vaccines demonstrated compatible findings (an acceptance prevalence of 85.3%), though this study’s target population included only physicians [27]. During the same period, our research group conducted a similar study (similar questionnaire, different mode of distribution and different target group) among personnel working in Greek hospitals and providing secondary health care services; the vaccine acceptance prevalence among the survey population was 77.7% [28]. The higher level of vaccination acceptance among our study group may be reflective of the primary health care personnel’s greater involvement in the Greek vaccination program, and may have been influenced by the questionnaire’s mode of distribution (online versus paper based). The estimated prevalence of vaccine acceptance in our study was higher than the actual vaccine coverage recorded by the Ministry of Health’s National Registry and communicated to ECDC during the study period (77% at least one dose and 70.8% fully vaccinated) [29]. However, our study estimates both the intention and attainment of vaccination, in contrast to the National Registry data, which show actual vaccinations.

Regarding the global situation, studies conducted prior to vaccination implementation presented generally lower acceptance rates [30,31,32,33,34], even when the studies’ target groups included professionals responsible for national vaccination project implementation [35]. However, a study in South Africa demonstrated a vaccine acceptance of 90.1% [36]. Many studies conducted, for example, in Germany [37], Canada [38], India [39] and the USA [40] following the release of vaccines describe a vaccine acceptance level comparable with our study. However, other studies conducted in Germany [41], the United Arabic Emirates [42], Czech Republic [43] and the USA [44] reveal lower vaccine acceptance levels compared to our study.

In our survey, no association with age, sex and gender variables was detected. However, several studies reported a higher vaccine acceptance by males and individuals of older age [34,38,43,45,46]. One Italian study supported younger age as a predictor of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [33].

Several surveys reported a lower COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among nurses compared to physicians [28,34,38,47], and our study confirms this observation. Nurses’ vaccine hesitancy could be considered as a risk factor for COVID-19 transmission, due to their prolonged and close contact with health facility users. Updating nursing educational curriculum to focus on public health issues and in particular vaccination as one of the most important measures to combat infectious diseases, collective responsibility, risk perception and communicable disease prevention, during both undergraduate and postgraduate studies, could increase nurses’ competencies in health promotion and improve their vaccine acceptance.

The seasonal influenza vaccination of PHCC personnel was one of the predictors for COVID-19 vaccination acceptance. Our results are in line with several similar studies where a strong correlation was observed [11,27,28,33,34,42,43,44,45,48,49].

Our survey revealed that participants who were well informed about COVID-19 vaccines were more likely to accept vaccination. Similar findings were reported by another study conducted in five European countries [11]. However, a better generic knowledge of or positive attitudes towards vaccination in general terms had no association with acceptance or hesitancy. Moreover, major reasons for vaccine hesitancy included inadequate information about COVID-19 vaccines and possible vaccine side effects. Most studies worldwide depict similar results [30,31,35,43,45], which underlines the need for specific and continuous information regarding COVID-19 vaccination, in order to improve relative knowledge and reduce concerns about safety and effectiveness.

According to our study results, participants with fewer concerns about vaccine novelty and the short timeframe for vaccine development were more prone to vaccination.

Concerning geographical data, certain health districts have lower vaccination rates compared to others. Specifically, participants working in health districts located in northern Greece show a greater level of vaccination hesitancy. The results are in line with a survey conducted by our research group in personnel of Greek hospitals [28]. This observation is significant in the context of a relative national vaccination campaign, as it reveals that national campaigns may have variable impacts in different areas.

In late July 2021, the Greek government introduced legislation regarding the mandatory vaccination for personnel working in health care facilities throughout the country. Our study indicates that more than half of the participants agreed with mandating COVID-19 vaccination for health care professionals. However, vaccine mandate studies are divided, both supporting [28,50] and against [41,51] the mandates. By the end of April 2022, more than 8 months after introducing legislation for the mandatory vaccination of HCW, 9.3% of HCW continue to refuse vaccination, despite financial and professional adverse consequences. The results of our survey depicted that mandatory legislation might not be 100% successful in addressing vaccine hesitancy.

Information sources are expected to be a factor for vaccine acceptance. Our study depicted that formal/national source of information may be facilitators for COVID-19 vaccination. Several surveys indicated that relying on traditional sources of information and governmental guidelines positively affects vaccination acceptance, while information sourced from social media and general context websites encourage vaccine hesitancy [19,27,33,37,52]. Intensive research in this field may be necessary and could improve understanding the dynamics of these findings.

Another noteworthy result identified is the strong correlation between PHCC personnel COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and adult population vaccination coverage against COVID-19 in each health district. This finding is similar to another survey that our research group conducted among personnel of Greek hospitals [28]. However, the higher level of correlation in the present survey might demonstrate the vast impact of PHCC personnel behavior in local communities and emphasizes the possibility of PHCC personnel acting as opinion leaders for the general population.

Our study has limitations: The sample was convenient although the response rate was acceptable for a hybrid format (online and paper-based) study [22]. Participation (selection) bias may have occurred, as vaccinated personnel may be more willing to participate, despite the anonymity provided through the online questionnaire. At face value, it seems that our study yields a low response rate, and since we were not able to collect data from non-respondents; this may be a source of selection bias. It should be noted that a low response rate to online surveys has been previously reported [53]. Nevertheless, our survey response rate of approximately 30% could be considered as relatively satisfactory, taking into account the online method of data collection employed during the era of COVID-19. Unfortunately, due to heavy workloads of PHCC personnel during the study period, the length of questionnaires should be limited to maximize participation. For convenience, useful information was not included in the questionnaire: Hepatitis B vaccination, recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination to the general population, revealing elements of character such as altruistic and self-serving behavior, reasons for vaccine hesitancy such religion or trust in pharmaceutical/formal authorities [7]. Despite these shortcomings, our study has the considerable advantages of a nationwide nature of HCWs sampled, and the use of a detailed questionnaire on a wide spectrum of knowledge, attitudes and practices of primary health care personnel towards vaccinations. The primary health care workforce could play a pivotal role in the promotion of vaccination coverage, including COVID-19 related vaccines, since primary care staff have a history of experience successfully delivering immunization programs [54]. Moreover, the primary care setting has the potential to combine facets of knowledge, attitudes, behavior, culture and health in the concept and practice of personalized care. In addition, patients feel comfortable receiving medical care from health care practitioners who are culturally compatible in understanding their concerns [55]. Consequently, the primary care environment is the best source of trusted information for those who are hesitant towards vaccination.

5. Conclusions

PHCC personnel appeared to accept the COVID-19 vaccine during the first months of 2021. However, specific occupational groups, such as nurses, demonstrated a greater hesitancy to the vaccine than others. Efforts should be made to combat the objections of hesitant employees and improve their acceptance towards new vaccines, as there are indications of their being a role model for the community. Several cultural and behavioral barriers might play a significant role to professionals denying COVID-19 vaccination, which seem to be present even after mandatory measures have been taken. Additional studies in the field could provide useful information and tools to tackle vaccine hesitancy more efficiently. Adequate and constant information/education about COVID-19 vaccines could be the major tool to increase vaccination coverage of both HCW and general population. Vaccination strategies should consider the reasons that HCW refused COVID-19 vaccines as reported by the responders of our study. Addressing fears and providing further information about vaccines through information campaigns for HCW could potentially increase vaccine coverage among HCW.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/vaccines10050765/s1, S1 Survey Questionnaire; S2 Table S6. Results of association between sources of information and correct knowledge/perceptions about vaccination and COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination acceptance; S3 Table S7. Results of association between demographical factors and other determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and correct knowledge and perceptions about vaccination and COVID-19 vaccines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A., K.F., M.S., C.H. and V.A.M.; Data curation, I.A.; Formal analysis, K.D.; Methodology, G.R., M.S., K.D., C.H. and V.A.M.; Project administration, I.A.; Resources, I.A., L.A., K.F., A.M., M.K., C.P., M.S., M.B., P.V., S.Z., E.T., F.N. and A.P.; Supervision, C.H. and V.A.M.; Writing—original draft, I.A., L.A., K.D. and V.A.M.; Writing—review and editing, L.A., G.R., M.S., C.H. and V.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics committee of the University of Thessaly (protocol number 49/13 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants of the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- COVID-19 Vaccines: Authorised | European Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-authorised#authorised-covid-19-vaccines-section (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-vaccines?topicsurvey=v8kj13)&gclid=Cj0KCQjwqp-LBhDQARIsAO0a6aKK0KrT5TUttU59Bh0kKEST-vHLAVIt1aNEVQJRCSeFdg5UoXpUbOAaAsoKEALw_wcB (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Hellenic National Public Health Organization: Daily Epidemiological Report of COVID-19 ISO WEEK 49. Available online: https://eody.gov.gr/ (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Number of First Doses Administered to Adults in EU/EEA Countries. Available online: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#uptake-tab (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Summary WHO SAGE Conclusions and Recommendations on Vaccine Hesitancy-Guide-to-Tailoring-Immunization-Programmes-TIP.pdf. 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/2_SAGE_Appendicies_Background_final.pdf?ua=12http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/187347/The (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Mereckiene, J.; Cotter, S.; Weber, J.T.; Nicoll, A.; D’Ancona, F.; Lopalco, P.L.; Johansen, K.; Wasley, A.M.; Jorgensen, P.; Lévy-Bruhl, D.; et al. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccination policies and coverage in Europe. Eurosurveillance 2012, 17, 20064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rachiotis, G.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Kremastinou, J.; Gourgoulianis, K.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. Low acceptance of vaccination against the 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) among healthcare workers in Greece. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patelarou, A.; Saliaj, A.; Galanis, P.; Pulomenaj, V.; Prifti, V.; Sopjani, I.; Mechili, E.A.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; Kicaj, E.; Kalokairinou, A.; et al. Predictors of nurses’ intention to accept COVID-19 vaccination: A cross-sectional study in five European countries. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 31, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danchin, M.; Biezen, R.; Manski-Nankervis, J.A.; Kaufman, J.; Leask, J. Preparing the public for COVID-19 vaccines: How can general practitioners build vaccine confidence and optimise uptake for themselves and their patients? Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National COVID-19 Vaccination Strategy/COVID-19 Vaccination. Available online: https://emvolio.gov.gr/diadikasia-emvoliasmou (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Mouchtouri, V.A.; Agathagelidou, E.; Kofonikolas, K.; Rousou, X.; Dadouli, K.; Pinaka, O.; Agathocleous, E.; Anagnostopoulou, L.; Chatziligou, C.; Christoforidou, E.P.; et al. Nationwide Survey in Greece about Knowledge, Risk Perceptions, and Preventive Behaviors for COVID-19 during the General Lockdown in April 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Available online: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#target-group-tab (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Sample Size Calculator by Raosoft, Inc. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Hellenic Republic Hellenic Statistical Authority Press Release Census of Health Centres and Other Units Providing Primary Health Care Services: Year 2019 Health Centres Health* Units Regional Medical Offices Multipurpose Regional Medical Offices Specialised Regional Medical Offices Local Medical Offices. 2020. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/ (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Aerny-Perreten, N.; Ma, B.; Felicitas Domínguez-Berjón, M.; Esteban-Vasallo, M.D.; García-Riolobos, C.; Mph, B.; Regional, M.; Authority, H. Participation and factors associated with late or non-response to an online survey in primary care. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannis, D.; Rachiotis, G.; Malli, F.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kotsiou, O.; Fradelos, E.C.; Giannakopoulos, K.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination among Greek Health Professionals. Vaccines 2021, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannis, D.; Malli, F.; Raptis, D.G.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Fradelos, E.C.; Daniil, Z.; Rachiotis, G.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices towards New Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of Health Care Professionals in Greece before the Outbreak Period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Callingham, R. Statistical Literacy: A Complex Hierarchical Construct 1. Available online: http://fehps.une.edu.au/serj (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Brtnikova, M.; Crane, L.A.; Allison, M.A.; Hurley, L.P.; Beaty, B.L.; Kempe, A. A method for achieving high response rates in national surveys of U.S. primary care physicians. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Status—ELSTAT. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/home/ (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Covid-19 National Vaccination Registry. Available online: https://emvolio.gov.gr/vaccinationtracker (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- WHO/Europe | Behavioural and Cultural Insights for Health—Publications. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/behavioural-and-cultural-insights-for-health/publications (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Maltezou, H.C.; Pavli, A.; Dedoukou, X.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Raftopoulos, V.; Drositis, I.; Bolikas, E.; Ledda, C.; Adamis, G.; Spyrou, A.; et al. Determinants of intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 among healthcare personnel in hospitals in Greece. Infect. Dis. Health 2021, 26, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinos, G.; Lamprinos, D.; Georgakopoulos, P.; Patoulis, G.; Vogiatzi, G.; Damaskos, C.; Papaioannou, A.; Sofroni, A.; Pouletidis, T.; Papagiannis, D.; et al. Reported COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Associated Factors among Members of Athens Medical Association: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotiadis, K.; Dadouli, K.; Avakian, I.; Bogogiannidou, Z.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Gogosis, K.; Speletas, M.; Koureas, M.; Lagoudaki, E.; Kokkini, S.; et al. Factors Associated with Healthcare Workers’ (HCWs) Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccinations and Indications of a Role Model towards Population Vaccinations from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Greece, May 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumulative Uptake (%) of at Least One Vaccine Dose in the Total Population in EU/EEA Countries. Available online: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html##national-ref-tab (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Szmyd, B.; Karuga, F.F.; Bartoszek, A.; Staniecka, K.; Siwecka, N.; Bartoszek, A.; Błaszczyk, M.; Radek, M. Attitude and Behaviors towards SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study from Poland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unroe, K.T.; Evans, R.; Weaver, L.; Rusyniak, D.; Blackburn, J. Willingness of Long-Term Care Staff to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine: A Single State Survey. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabamba Nzaji, M.; Kabamba Ngombe, L.; Ngoie Mwamba, G.; Banza Ndala, D.B.; Mbidi Miema, J.; Luhata Lungoyo, C.; Lora Mwimba, B.; Cikomola Mwana Bene, A.; Mukamba Musenga, E. Acceptability of Vaccination Against COVID-19 Among Healthcare Workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmatic Obs. Res. 2020, 11, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Murri, R.; Segala, F.V.; Cerruti, L.; Abdulle, A.; Saracino, A.; Bavaro, D.F.; Fantoni, M. Attitudes towards Anti-SARS-CoV2 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: Results from a National Survey in Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneux-Brunon, A.; Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Tardy, B.; Rozaire, O.; Frappe, P.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: A cross-sectional survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 108, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, P.; Scronias, D.; Dauby, N.; Adedzi, K.A.; Gobert, C.; Bergeat, M.; Gagneur, A.; Dubé, E. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: A survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2002047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, O.V.; Stead, D.; Singata-Madliki, M.; Batting, J.; Wright, M.; Jelliman, E.; Abrahams, S.; Parrish, A. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine among the Healthcare Workers in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: A Cross Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann-Littig, C.; Braunisch, M.C.; Kranke, P.; Popp, M.; Seeber, C.; Fichtner, F.; Littig, B.; Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; Allwang, C.; Frank, T.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Germany. Vaccines 2021, 9, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzieciolowska, S.; Hamel, D.; Gadio, S.; Dionne, M.; Gagnon, D.; Robitaille, L.; Cook, E.; Caron, I.; Talib, A.; Parkes, L.; et al. Covid-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal among Canadian healthcare workers: A multicenter survey. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, P.; Ts, S.K.; Bv, M.M.; Ghorai, P.A.; Rupert, E.; Shetty, D.P. Uptake and Impact of Vaccination Against COVID-19 among Healthcare Workers- Evidence from a Multicentre Study. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 50, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth-Manikowski, S.M.; Swirsky, E.S.; Gandhi, R.; Piscitello, G. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among health care workers, communication, and policy-making. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganslmeier, A.; Engelmann, T.; Lucke, M.; Täger, G.; Pfeifer, M.; Scherer, M.A. Attitude of health care workers towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. MMW Fortschr. Med. 2021, 163, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddik, B.; Al-Bluwi, N.; Shukla, A.; Barqawi, H.; Alsayed, H.A.H.; Sharif-Askari, N.S.; Temsah, M.-H.; Bendardaf, R.; Hamid, Q.; Halwani, R. Determinants of healthcare workers perceptions, acceptance and choice of COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-sectional study from the United Arab Emirates. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štěpánek, L.; Janošíková, M.; Nakládalová, M.; Štěpánek, L.; Boriková, A.; Vildová, H. Motivation to COVID-19 Vaccination and Reasons for Hesitancy in Employees of a Czech Tertiary Care Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, D.J.; Ojo, A.; Gurley, T.; Le Master, J.W.; Meyer, M.; Wild, D.M.; Mustafa, R.A. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination Among Health System Personnel. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Mustapha, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Price, J.H. The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohl, A.; Afflerbach, C.; Lurz, C.; Brune, B.; Ohmann, T.; Weichert, V.; Zeiger, S.; Dudda, M. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination among Front-Line Health Care Workers: A Nationwide Survey of Emergency Medical Services Personnel from Germany. Vaccines 2021, 9, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuown, A.; Ellis, T.; Miller, J.; Davidson, R.; Kachwala, Q.; Medeiros, M.; Mejia, K.; Manoraj, S.; Sidhu, M.; Whittington, A.M.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination intent among London healthcare workers. Adv. Access Publ. 2021, 71, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, G.; Blanco, B.; Casas, I.; Huertas, A.; Sánchez, M.A.; Auñón, M.; Viñas, J.; Esteve, M. Attitudes of Spanish hospital staff towards COVID-19 vaccination and vaccination rates. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, D.; Shao, L.; Jin, J.; He, Q. Intention to COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors among health care workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Peruzzi, S.; Balzarini, F.; Ranzieri, S. Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign. Vaccines 2021, 9, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, K.; Gogoi, M.; Martin, C.A.; Papineni, P.; Lagrata, S.; Nellums, L.B.; McManus, I.C.; Guyatt, A.L.; Melbourne, C.; Bryant, L.; et al. Healthcare workers’ views on mandatory SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the UK: A cross-sectional, mixed-methods analysis from the UK-REACH study. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Massey, P.M.; Stimpson, J.P. Primary Source of Information About COVID-19 as a Determinant of Perception of COVID-19 Severity and Vaccine Uptake: Source of Information and COVID-19. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3088–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Yan, Z. Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: A systematic review. Comput. Human Behav. 2010, 26, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, A.; Harnden, A.; Lim, W.S. COVID-19 vaccination programme: A central role for primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, J.G.; Katzman, J.W. Primary Care Clinicians as COVID-19 Vaccine Ambassadors. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 21501327211007026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).