An Online Experiment of NHS Information Framing on Mothers’ Vaccination Intention of Children against COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

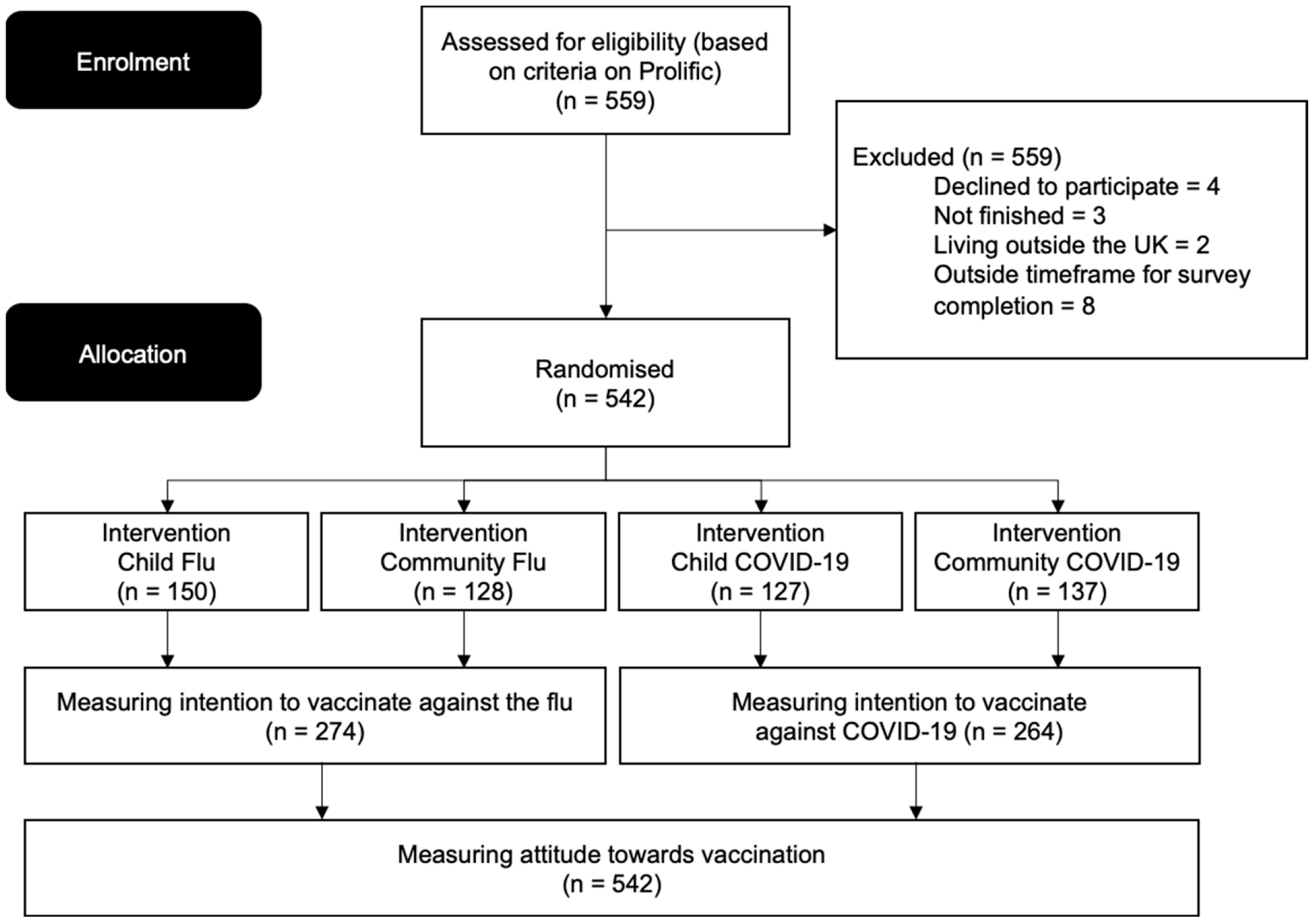

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Sample

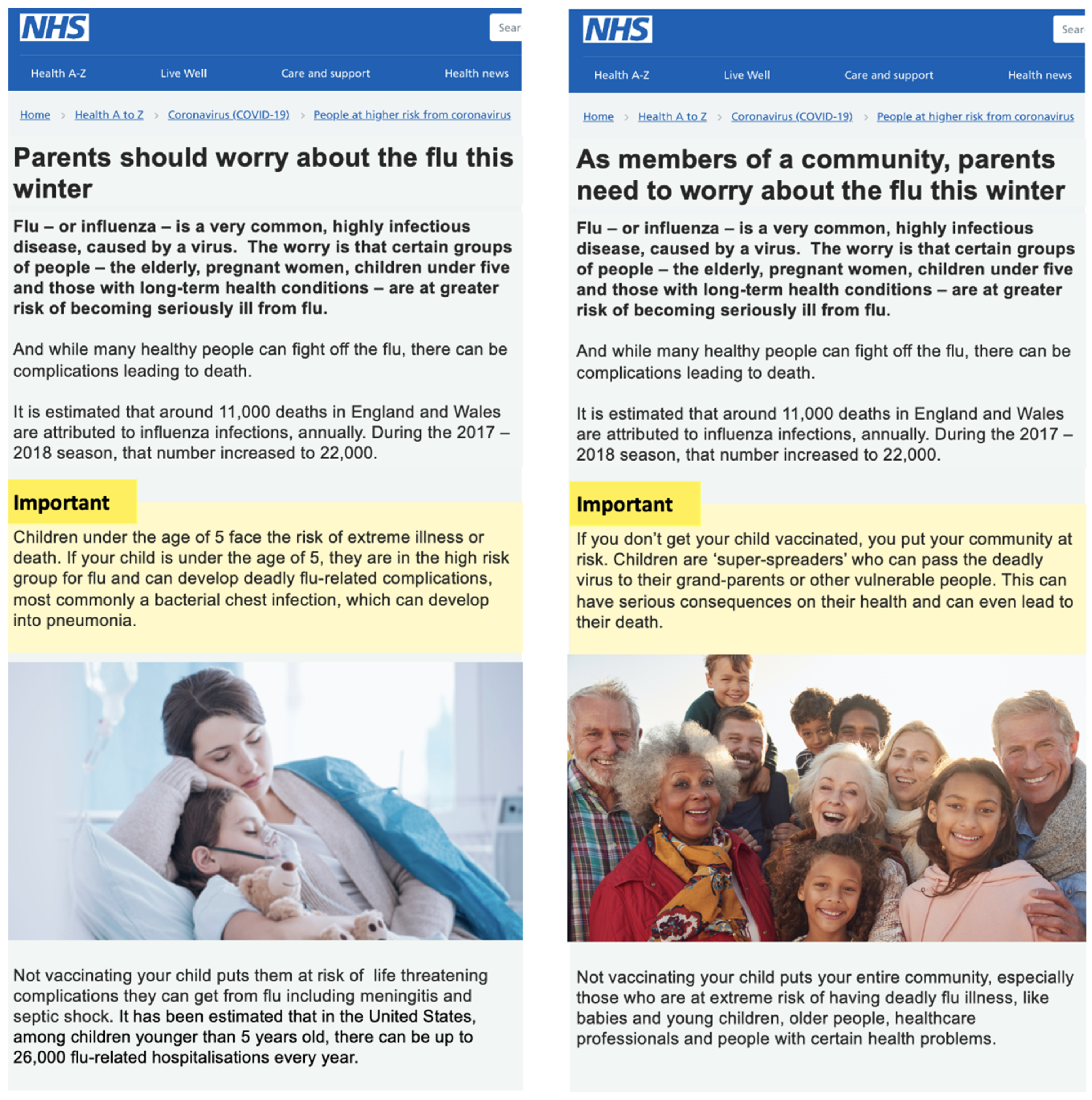

2.2. Design

2.3. Materials

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Intention to Vaccinate

2.4.2. Attitude towards Vaccination

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Ethical Approval

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exclusion Criteria

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2.1. In Relation to Vaccination Intention

3.2.2. In Relation to Vaccination Attitude

3.3. Treatment Effects

3.3.1. On Vaccination Intention

3.3.2. On Vaccination Attitude

3.3.3. Effect on Vaccination Intention & Attitude Controlling for Demographic Factors

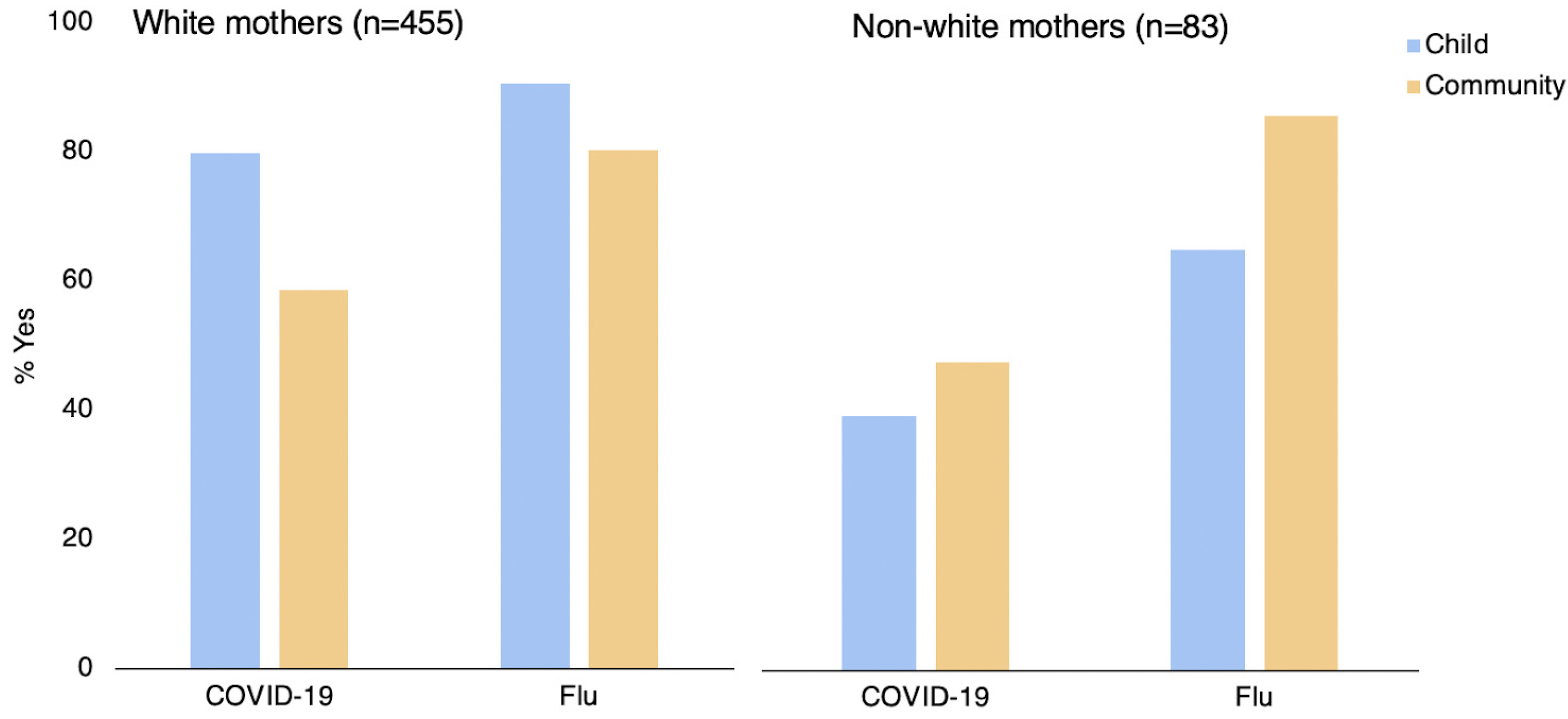

3.4. Exploratory Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Worldmeters. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. 2022. Available online: http://www.worldmeters.info/Coronavirus (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- UNICEF. Child Mortality and COVID-19. 2022. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/covid-19/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Han, B.; Song, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, W.; Ma, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Li, M.; Lian, X.; Jiao, W.; Wang, L.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthy children and adolescents: A double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government; Office of National Statistics. Parenting in lockdown: Coronavirus and the effects on Work-Life Balance. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Gowda, C.; Dempsey, A.F. The rise (and fall?) of parental vaccine hesitancy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Osterholm, M.T.; Kelley, N.S.; Sommer, A.; Belongia, E.A. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Schneider, C.R.; Dryhurst, S.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; van der Linden, S. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 201199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, J.A. Neoliberal Mothering and Vaccine Refusal: Imagined Gated Communities and the Privilege of Choice. Gend. Soc. 2014, 28, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D.; Douglas, K.M. The Effects of Anti-Vaccine Conspiracy Theories on Vaccination Intentions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damnjanović, K.; Graeber, J.; Ilić, S.; Lam, W.Y.; Lep, Ž.; Morales, S.; Pulkkinen, T.; Vingerhoets, L. Parental Decision-Making on Childhood Vaccination. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, A.; Saville, A.W.; Albertin, C.; Zimet, G.; Breck, A.; Helmkamp, L.; Vangala, S.; Dickinson, L.M.; Rand, C.; Humiston, S.; et al. Parental Hesitancy About Routine Childhood and Influenza Vaccinations: A National Survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20193852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, A.; Ernst, K. Story and science. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1795–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laskowski, M. Nudging towards Vaccination: A Behavioral Law and Economics Approach to Childhood Immunization Policy. Tex. Law Rev. 2016, 94, 601. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Rothman, A.J.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science into Action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2017, 18, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dolan, P.; Hallsworth, M.; Halpern, D.; King, D.; Metcalfe, R.; Vlaev, I. Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelfranchi, C. Towards a Cognitive Memetics: Socio-Cognitive Mechanisms for Memes Selection and Spreading. J. Memet.-Evol. Models Inf. Transm. 2001, 2001, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kestenbaum, L.A.; Feemster, K.A. Identifying and Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy. Pediatr. Ann. 2015, 44, e71–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horne, Z.; Powell, D.; Hummel, J.E.; Holyoak, K.J. Countering antivaccination attitudes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10321–10324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J.; Richey, S.; Freed, G.L. Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e835–e842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Healy, C.M.; Pickering, L.K. How to Communicate with Vaccine-Hesitant Parents. Pediatrics 2011, 127, S127–S133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadique, Z.; Devlin, N.; Edmunds, W.J.; Parkin, D. The Effect of Perceived Risks on the Demand for Vaccination: Results from a Discrete Choice Experiment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isler, O.; Isler, B.; Kopsacheilis, O.; Ferguson, E. Limits of the social-benefit motive among high-risk patients: A field experiment on influenza vaccination behaviour. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, M.; Taylor, E.G.; Atkins, K.E.; Chapman, G.B.; Galvani, A.P. Stimulating Influenza Vaccination via Prosocial Motives. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanders, J.G.; Spruijt, P.; van Dijk, M.; Elberse, J.; Lambooij, M.S.; Kroese, F.M.; de Bruin, M. Understanding a national increase in COVID-19 vaccination intention, the Netherlands, November 2020–March 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euser, S.; Kroese, F.M.; Derks, M.; de Bruin, M. Understanding COVID-19 vaccination willingness among youth: A survey study in the Netherlands. Vaccine 2022, 40, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, R.; Betsch, C.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C. Exploring and Promoting Prosocial Vaccination: A Cross-Cultural Experiment on Vaccination of Health Care Personnel. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6870984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luyten, J.; Bruyneel, L.; van Hoek, A.J. Assessing vaccine hesitancy in the UK population using a generalized vaccine hesitancy survey instrument. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2494–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Sheriff, M.; Hendrix, K.S.; Downs, S.M.; Sturm, L.A.; Zimet, G.D.; Finnell, S.M.E. The Role of Herd Immunity in Parents’ Decision to Vaccinate Children: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C. On the benefits of explaining herd immunity in vaccine advocacy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, K.S.; Finnell, S.M.E.; Zimet, G.D.; Sturm, L.A.; Lane, K.A.; Downs, S.M. Vaccine Message Framing and Parents’ Intent to Immunize Their Infants for MMR. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e675–e683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NHS Digital. Childhood Vaccination Coverage Statistics. Childhood Vaccination Coverage Statistics—England 2018-19; NHS Digital: Leeds, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Verelst, F.; Willem, L.; Kessels, R.; Beutels, P. Individual decisions to vaccinate one’s child or oneself: A discrete choice experiment rejecting free-riding motives. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 207, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolific. 2022. Available online: https://www.prolific.co/ (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Palan, S.; Schitter, C. Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2018, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakens, D.D.; Evers, E.R.K. Sailing From the Seas of Chaos Into the Corridor of Stability. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 9, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- List, J.; Sadoff, S.; Wagner, M. So you want to run an experiment, now what? Some simple rules of thumb for optimal experimental design. Exp. Econ. 2011, 14, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K.P. An overview of randomization techniques: An unbiased assessment of outcome in clinical research. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 4, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, J.; Nina, H.; David, M.; Jessica, M.; Laura, S.; Dan, W. Public Satisfaction with the NHS and Social Care in 2019: Results and Trends from the British Social Attitudes Survey. British Social Attitudes: Public Satisfaction with the NHS and Social Care in 2019; Nuffield Trust: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/public-satisfaction-with-the-nhs-and-social-care-in-2019-results-and-trends-from-the-british-social-attitudes-survey (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Kahneman, D.; Thaler, R.H. Anomalies: Utility Maximization and Experienced Utility. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintulová, L.L. The impact of the emotions that frame mothers’ decision-making about the vaccination of toddlers. Kontakt 2019, 21, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schlochtermeier, L.H.; Kuchinke, L.; Pehrs, C.; Urton, K.; Kappelhoff, H.; Jacobs, A.M. Emotional Picture and Word Processing: An fMRI Study on Effects of Stimulus Complexity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, L.B.; Goodwin, R. Determinants of adults’ intention to vaccinate against pandemic swine flu. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinn, S.C.; Parmer, J.; Freimuth, V.S.; Hilyard, K.M.; Musa, D.; Kim, K.H. Exploring Communication, Trust in Government, and Vaccination Intention Later in the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic: Results of a National Survey. Biosecur. Bioterror. Biodef. Strat. Pract. Sci. 2013, 11, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, L. Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Schmid, P.; Heinemeier, D.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C.; Böhm, R. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gallup. Wellcome Global Monitor—First Wave Findings? 2019. Available online: https://wellcome.ac.uk/reports/wellcome-global-monitor/2018 (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Chapman, G.B.; Coups, E.J. Predictors of Influenza Vaccine Acceptance among Healthy Adults. Prev. Med. 1999, 29, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enticott, J.; Gill, J.S.; Bacon, S.L.; Lavoie, K.L.; Epstein, D.S.; Dawadi, S.; Teede, H.J.; Boyle, J. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: A cross-sectional analysis—implications for public health communications in Australia. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The SAGE Working Group. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy; Sage Report; WHO SAGE Working Group: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Devine, P.G. On the motivational nature of cognitive dissonance: Dissonance as psychological discomfort. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government; Office for National Statistics. Families and the Labour Market, UK: 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/familiesandthelabourmarketengland/2019 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- UK Government; Office for National Statistics. Average Household Income, UK: Financial Year 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/householddisposableincomeandinequality/financialyear2020 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- UK Government; Office for National Statistics. Mean Age of Mother at Birth of First Child, by Highest Achieved Educational Qualification, 1996 to 2016, England and Wales. 2018. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/conceptionandfertilityrates/adhocs/008981meanageofmotheratbirthoffirstchildbyhighestachievededucationalqualification1996to2016englandandwales (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- UK Government; Office for National Statistics. Families and Households, UK: 2022. 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/bulletins/familiesandhouseholds/latest (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Karlsson, L.C.; Soveri, A.; Lewandowsky, S.; Karlsson, L.; Karlsson, H.; Nolvi, S.; Karukivi, M.; Lindfelt, M.; Antfolk, J. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: The case of COVID-19. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 172, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, L.; Böhm, R.; Meier, N.W.; Betsch, C. Vaccination as a social contract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14890–14899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunreuther, H. Mitigating disaster losses through insurance. J. Risk Uncertain. 1996, 12, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R. Individualism, Collectivism and Ethnic Identity: Cultural Assumptions in Accounting for Caregiving Behaviour in Britain. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2012, 27, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, J.-W.; Staman, J.; Krouwel, A.P. Increased conspiracy beliefs among ethnic and Muslim minorities. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2018, 32, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, B.; Galizzi, M.M.; Sanders, J.G. Heterogeneity in Risk-Taking During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence From the UK Lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 643653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, C.J.; Tipton, E.; Yeager, D.S. Behavioural science is unlikely to change the world without a heterogeneity revolution. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vietri, J.T.; Li, M.; Galvani, A.P.; Chapman, G.B. Vaccinating to Help Ourselves and Others. Med. Decis. Mak. 2011, 32, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prolific Team. What Are the Advantages and Limitations of an Online Sample? 2022. Available online: https://researcher-help.prolific.co/hc/en-gb/articles/360009501473-What-are-the-advantages-and-limitations-of-an-online-sample- (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Minkov, M.; Hofstede, G. Hofstede’s Fifth Dimension: New evidence from the world values survey. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2010, 43, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Demographic Factors | Vaccination Intention | Demographic Factors | VCI | 4C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | Stand. Est | 95% CI | p-Value | Stand. Est | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White (n = 455) | Reference | White (n = 459) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Non-white (n = 83) | 0.381 | 0.224–0.649 | <0.001 | Non-white (n = 83) | −0.440 | −0.679–−0.202 | <0.001 | −0.457 | −0.695–−0.218 | <0.001 |

| Relationship status | ||||||||||

| In a relationship (n = 480) | Reference | In a relationship (n = 484) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Not in a relationship (n = 58) | 0.661 | 0.346–1.263 | 0.21 | Not in a relationship (n = 58) | −0.237 | −0.525–0.050 | 0.106 | −0.162 | −0.450–0.126 | 0.270 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Higher education (n = 333) | Reference | Higher education (n = 335) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Secondary education (n = 205) | 0.821 | 0.535–1.259 | 0.391 | Secondary education (n = 207) | 0.005 | −0.170–0.179 | 0.958 | −0.106 | −0.281–0.068 | 0.232 |

| Region | ||||||||||

| London (n = 60) | Reference | London (n = 61) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| England outside London (n = 408) | 1.288 | 0.659–2.517 | 0.458 | England outside London (n = 411) | 0.156 | −0.122–0.435 | 0.27 | 0.174 | −0.105–0.453 | 0.220 |

| Other UK (n = 68) | 1.276 | 0.544–2.992 | 0.575 | Other UK (n = 68) | 0.190 | −0.157–0.537 | 0.282 | 0.233 | −0.115–0.580 | 0.189 |

| Employment | ||||||||||

| Employed Full-time (n = 164) | Reference | Employed Full-time (n = 166) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Employed Part-time (n = 191) | 1.012 | 0.600–1.709 | 0.963 | Employed Part-time (n = 192) | 0.067 | −0.137–0.271 | 0.518 | 0.08 | −0.124–0.285 | 0.440 |

| Not working (n = 139) | 0.845 | 0.486–1.469 | 0.551 | Not working (n = 140) | 0.078 | −0.147–0.304 | 0.494 | 0.206 | −0.002–0.432 | 0.074 |

| Mother age | ||||||||||

| 18-24 (n = 34) | Reference | 18-24 (n = 34) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 25-34 (n = 273) | 1.211 | 0.529–2.769 | 0.651 | 25-34 (n = 276) | 0.072 | 0.421–0.277 | 0.686 | 0.02 | −0.329–0.370 | 0.909 |

| 35 or more (n = 231) | 1.467 | 0.633–3.401 | 0.372 | 35 or more (n = 232) | 0.038 | −0.314–0.391 | 0.831 | 0.221 | 0.132–0.574 | 0.220 |

| Number of children | ||||||||||

| 1 (n = 391) | Reference | 1 (n = 395) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 2 or more (n = 147) | 0.73 | 0.468–1.138 | 0.165 | 2 or more (n = 147) | −0.193 | −0.379–−0.007 | 0.042 | −0.241 | −0.427–−0.055 | 0.011 |

| Household income | ||||||||||

| Below £30K (n = 149) | Reference | Below £30K (n = 151) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| From £30K to £50K (n = 193) | 1.523 | 0.888–2.611 | 0.126 | From £30K to £50K (n = 194) | 0.416 | 0.191–0.642 | <0.001 | 0.361 | 0.135–0.587 | 0.002 |

| From £50K to £70K (n = 103) | 1.506 | 0.782–2.898 | 0.22 | From £50K to £70K (n = 104) | 0.499 | 0.231–0.769 | <0.001 | 0.474 | 0.205–0.744 | <0.001 |

| More than £70K (n = 93) | 1.699 | 0.842–3.429 | 0.139 | More than £70K (n = 93) | 0.598 | 0.216–0.781 | <0.001 | 0.398 | 0.115–0.681 | 0.006 |

| Intervention Effects and Demographic Variables | Vaccination Intention | Intervention Effects and Demographic Variables | VCI | 4C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | Stand. Est | 95% CI | p-Value | Stand. Est | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Risk (IV1) | ||||||||||

| Community frame (n = 263) | Reference | Community frame (n = 265) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Child frame (n = 275) | 2.135 | 1.232–3.698 | 0.007 | Child frame (n = 277) | 0.241 | 0.006–0.476 | 0.044 | 0.175 | −0.060–0.411 | 0.143 |

| Disease (IV2) | ||||||||||

| COVID-19 (n =264) | Reference | COVID-19 (n = 264) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Flu (n = 274) | 3.271 | 1.824–5.866 | <0.001 | Flu (n = 278) | 0.119 | −0.113–0.352 | 0.314 | 0.139 | −0.094–0.372 | |

| Interaction | ||||||||||

| IV1–IV2 | 0.783 | 0.327–1.871 | 0.582 | IV1–IV2 | −0.071 | −0.398–0.255 | 0.666 | −0.004 | −0.331–0.323 | 0.982 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White (n = 455) | Reference | White (n = 459) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Non-white (n = 83) | 0.368 | 0.210–0.645 | <0.001 | Non-white (n = 83) | −0.453 | −0.453–−0.692 | <0.001 | −0.459 | −0.684–−0.208 | <0.001 |

| Relationship status | ||||||||||

| In a relationship (n = 480) | Reference | In a relationship (n = 484) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Not in a relationship (n = 58) | 0.624 | 0.315–1.238 | 0.177 | Not in a relationship (n = 58) | −0.254 | −0.542–0.033 | 0.083 | −0.169 | −0.458–0.119 | 0.249 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Higher education (n = 333) | Reference | Higher education (n = 335) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Secondary education (n = 205) | 0.792 | 0.507–1.239 | 0.307 | Secondary education (n = 207) | 0.004 | 0.169–0.179 | 0.956 | −0.108 | −0.282–0.066 | 0.222 |

| Region | ||||||||||

| London (n = 60) | Reference | London (n = 61) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| England outside London (n = 408) | 1.062 | 0.526–2.143 | 0.742 | England outside London (n = 411) | 0.124 | −0.154–0.402 | 0.383 | 0.141 | −0.138–0.419 | 0.321 |

| Other UK (n = 68) | 1.016 | 0.416–2.482 | 0.899 | Other UK (n = 68) | 0.150 | −0.197–0.497 | 0.397 | 0.193 | −0.155–0.541 | 0.277 |

| Employment | ||||||||||

| Employed Full-time (n = 164) | Reference | Employed Full-time (n = 166) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Employed Part-time (n = 191) | 1.077 | 0.624–1.857 | 0.790 | Employed Part-time (n = 192) | 0.078 | −0.126–0.282 | 0.452 | 0.088 | −0.117–0.292 | 0.399 |

| Not working (n = 139) | 0.933 | 0.525–1.659 | 0.815 | Not working (n = 140) | 0.088 | −0.137–0.314 | 0.442 | 0.217 | −0.009–0.443 | 0.060 |

| Mother age | ||||||||||

| 18-24 (n = 34) | Reference | 18-24 (n = 34) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 25-34 (n = 273) | 1.156 | 0.564–2.234 | 0.739 | 25-34 (n = 276) | −0.087 | −0.435–0.261 | 0.624 | 0.002 | −0.347–0.351 | 0.990 |

| 35 or more (n = 231) | 1.443 | 0.438–2.562 | 0.409 | 35 or more (n = 232) | 0.025 | −0.326–0.377 | 0.888 | 0.204 | −0.149–0.556 | 0.257 |

| Number of children | ||||||||||

| 1 (n = 391) | Reference | 1 (n = 395) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| 2 or more (n = 147) | 0.738 | 0.463–1.176 | 0.202 | 2 or more (n = 147) | −0.172 | −0.358–−0.001 | 0.069 | −0.224 | −0.410–−0.038 | 0.019 |

| Household income | ||||||||||

| Below £30K (n = 149) | Reference | Below £30K (n = 151) | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| From £30K to £50K (n = 193) | 1.659 | 0.943–2.919 | 0.079 | From £30K to £50K (n = 194) | 0.421 | 0.196–0.646 | <0.001 | 0.368 | 0.143–0.594 | 0.001 |

| From £50K to £70K (n = 103) | 1.588 | 0.806–3.130 | 0.181 | From £50K to £70K (n = 104) | 0.500 | 0.232–0.768 | <0.001 | 0.477 | 0.209–0.745 | <0.001 |

| More than £70K (n = 93) | 1.725 | 0.830–3.586 | 0.144 | More than £70K (n = 93) | 0.504 | 0.223–0.786 | <0.001 | 0.399 | 0.117–0.682 | 0.006 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Hoecke, A.L.; Sanders, J.G. An Online Experiment of NHS Information Framing on Mothers’ Vaccination Intention of Children against COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050720

Van Hoecke AL, Sanders JG. An Online Experiment of NHS Information Framing on Mothers’ Vaccination Intention of Children against COVID-19. Vaccines. 2022; 10(5):720. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050720

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Hoecke, Audrey L., and Jet G. Sanders. 2022. "An Online Experiment of NHS Information Framing on Mothers’ Vaccination Intention of Children against COVID-19" Vaccines 10, no. 5: 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050720

APA StyleVan Hoecke, A. L., & Sanders, J. G. (2022). An Online Experiment of NHS Information Framing on Mothers’ Vaccination Intention of Children against COVID-19. Vaccines, 10(5), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10050720