COVID-19 Vaccines and Hyperglycemia—Is There a Need for Postvaccination Surveillance?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

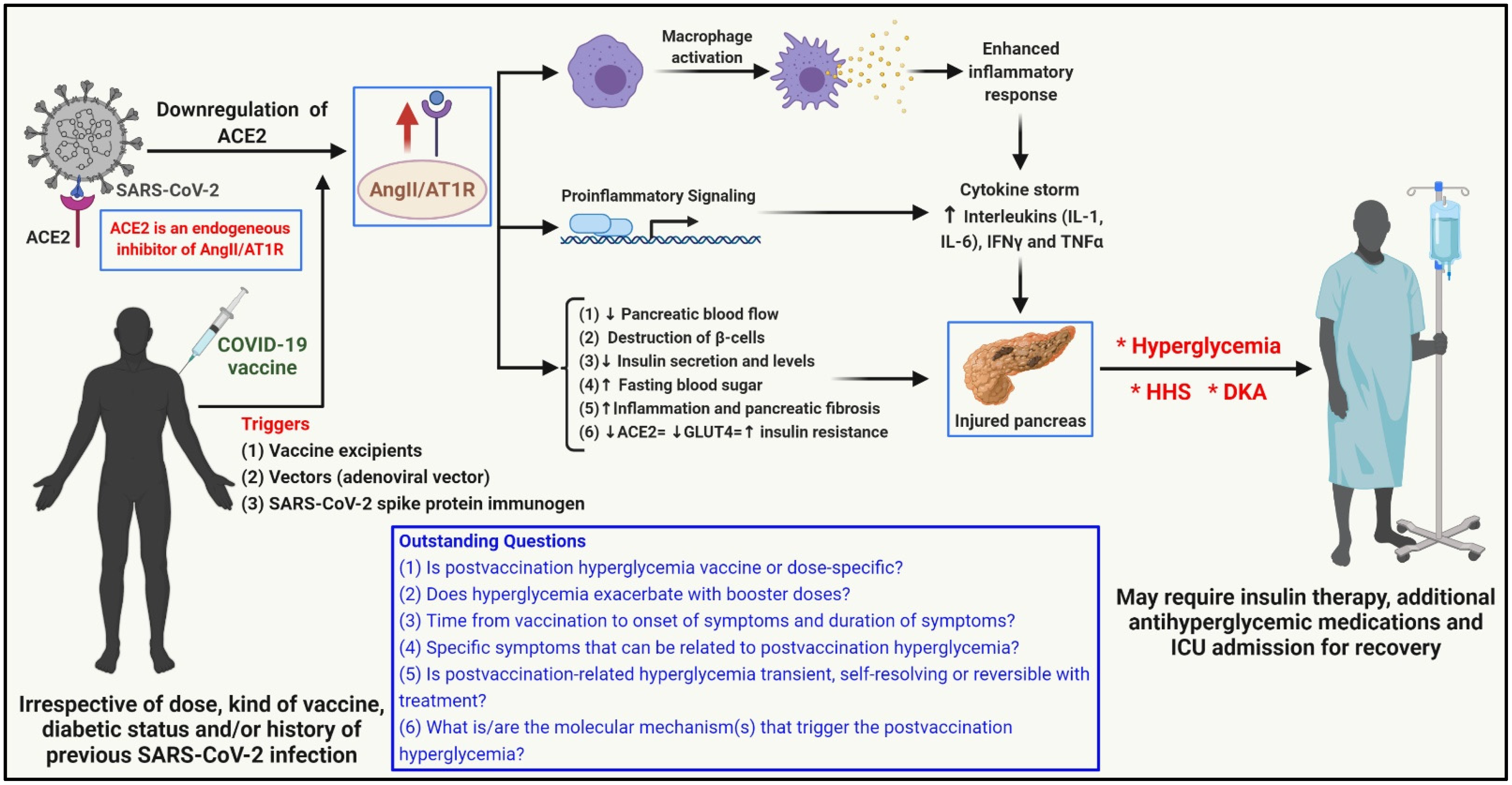

2. Vaccine-Induced Hyperglycemia (ViHG)—Case Reports

3. Possible Mechanism(s) of ViHG

4. Recommendations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| AngII | angiotensin II |

| AT1R | angiotensin II type 1 receptor |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DKA | diabetic ketoacidosis |

| GBS | Guillain-Barré syndrome |

| GLUT4 | glucose transporter 4 |

| HHS | hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| IFNγ | interferon gamma |

| IL-1/6 | interleukin 1/6 |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| RAAS | renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system |

| SAE | severe adverse events |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| ViHG | vaccination-induced hyperglycemia |

| VITT | vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- JHU. Coronavirus Resource Center. 2022. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- WHO. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- WHO. Update on Omicron. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-11-2021-update-on-omicron (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Samuel, S.M.; Varghese, E.; Büsselberg, D. Therapeutic Potential of Metformin in COVID-19: Reasoning for Its Protective Role. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Vaccines Safety. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-vaccines-safety (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- CDC. Selected Adverse Events Reported after COVID-19 Vaccination. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/adverse-events.html#:~:text=A%20review%20of%20reports%20indicates,contributed%20to%20six%20confirmed%20deaths%20 (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Varghese, E.; Samuel, S.M.; Liskova, A.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D. Diabetes and coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): Molecular mechanism of Metformin intervention and the scientific basis of drug repurposing. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.A.; Abbara, A.; Dhillo, W.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the Endocrine System: A Mini-review. Endocrinology 2022, 163, bqab203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunti, K.; Del Prato, S.; Mathieu, C.; Kahn, S.E.; Gabbay, R.A.; Buse, J.B. COVID-19, Hyperglycemia, and New-Onset Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 2645–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rumaileh, M.A.; Gharaibeh, A.M.; Gharaibeh, N.E. COVID-19 Vaccine and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State. Cureus 2021, 13, e14125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.E.; Vathenen, R.; Henson, S.M.; Finer, S.; Gunganah, K. Acute hyperglycaemic crisis after vaccination against COVID-19: A case series. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Sajan, A.; Tomer, Y. Hyperglycemic Emergencies Associated With COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Series and Discussion. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvab141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Ghosh, A.; Dutta, K.; Tyagi, K.; Misra, A. Exacerbation of hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes after vaccination for COVID19: Report of three cases. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2021, 15, 102151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, K.; Spanou, L. Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2011, 5, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ClinLab-Navigator. Hemoglobin A1c. 2022. Available online: http://www.clinlabnavigator.com/hemoglobin-a1c.html#:~:text=HbA1c%20is%20a%20weighted%20average,levels%20within%201%2D2%20weeks (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Brittain, C.; Christian, V.; Mahaseth, H.; Vadlamudi, R. S1674 Recurrent Acute Pancreatitis Following COVID-19 Vaccine—A Case Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, S748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślewicz, A.; Dudek, M.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I.; Jabłecka, A.; Lesiak, M.; Korzeniowska, K. Pancreatic Injury after COVID-19 Vaccine-A Case Report. Vaccines 2021, 9, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkash, O.; Sharko, A.; Farooqi, A.; Ying, G.W.; Sura, P. Acute Pancreatitis: A Possible Side Effect of COVID-19 Vaccine. Cureus 2021, 13, e14741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, T.; Connor, S.; Stedman, C.; Doogue, M. A case of acute necrotising pancreatitis following the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 88, 1385–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lung, D.C.; Ye, Z.; Song, W.; Liu, F.F.; Cai, J.P.; Wong, W.M.; Yip, C.C.; et al. Intravenous injection of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine can induce acute myopericarditis in mouse model. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witberg, G.; Barda, N.; Hoss, S.; Richter, I.; Wiessman, M.; Aviv, Y.; Grinberg, T.; Auster, O.; Dagan, N.; Balicer, R.D.; et al. Myocarditis after COVID-19 Vaccination in a Large Health Care Organization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 2132–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VigiAccess. WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring. 2022. Available online: http://www.vigiaccess.org/ (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Effect of mRNA Based-Covid-19 Vaccine on Blood Glucose Levels Recorded by Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Patients With a History of Diabetes Mellitus Type I and Type II. 2021. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04923386?term=vaccine%2C+hyperglycemia&cond=COVID-19&draw=2&rank=1 (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Glycemic Effects of COVID-19 Booster Vaccine in Type 1 Diabetes. 2022. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05233592?term=vaccine%2C+hyperglycemia&cond=COVID-19&draw=2&rank=2 (accessed on 6 March 2022).

| Gender/Age (Years) | Case 1 [11] Male/59 | Case 2 [11] Male/68 | Case 3 [11] Male/53 | Case 4 [10] Male/58 | Case 5 [12] Female/52 | Case 6 [12] Male/59 | Case 7 [12] Male/87 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 31.12 | 32.51 | 35.05 | Data unavailable | 32.5 | 27.7 | 26 |

| History of diabetes | No | Prediabetic | Prediabetic | No | No | T2DM | T2DM |

| Previous history of COVID-19 infection | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | No | Yes | Yes |

| Type of vaccine | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AstraZeneca) | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AstraZeneca) | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AstraZeneca) | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine | mRNA-1273 Moderna vaccine | mRNA-1273 Moderna vaccine |

| Symptoms | Osmotic symptoms of hyperglycemia (polydipsia/polyuria) | Osmotic symptoms of hyperglycemia (polydipsia/polyuria) | Osmotic symptoms of hyperglycemia (polydipsia/polyuria) | Nocturia, polyuria, and polydipsia, severely dehydrated, disoriented, and significant weight loss | Polyuria, polydipsia, lightheadedness, and dysgeusia | Blurry vision, dry mouth, and polyuria | Fatigue, myalgia, weakness and altered mental status, polydipsia (despite increased fluid intake), confused, and poor appetite |

| Dose of Vaccine—days to presentation/hospitalization | First dose—21 days | First dose—36 days | First dose—20 days | Second dose—6 days | First dose—3 days | First dose—2 days | First dose—10 days |

| Blood glucose levels (mg/dL) at time of hospitalization | 595 | 919 | 577 | 1253 | 1062 | 847 | 923 |

| C-peptide (normal range) | 235 pmol/L (370–1470 pmol/L) | 561 pmol/L (370–1470 pmol/L) | 377 pmol/L (370–1470 pmol/L) | 1.1 ng/mL (1.10–4.40 ng/mL) | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report |

| HbA1c (%) (pre-episode) | 5.6 (~37 months prior) | 6.5 (~24 months prior) | 6.4 (~18 months prior) | Data unavailable (however, FBS ranged 74–120 mg/dL for past 3 years) | 5.5–6.2 (~24 months prior) | 7.5 (~8 weeks prior) | 7.0 (~8 weeks prior) |

| * HbA1c (%) (during hospitalization) | 14.1 | 14.7 | 17.1 | 13.0 | 12 | 13.2 | Data unavailable in case report |

| Diagnosis | Hyperglycemic ketosis | Mixed HHS/DKA | DKA | HHS | T2DM and Nonketotic HHS | HHS | HHS and DKA |

| Treatment/intervention | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | In hospital: Hydration, insulin infusion, transitioning to subcutaneous multiple bolus of insulin. Further transitioning to glargine and insulin. Discharged: On insulin, which was tapered off, then discontinued and further simplified to only metformin. | In hospital: Hydration, insulin infusion, transitioning to subcutaneous basal bolus of insulin. Discharged: On glargine, lispro, and metformin, which was further simplified to only metformin and weekly dulaglutide. | In hospital: Hydration, insulin infusion, transitioning to subcutaneous basal bolus of glargine and lispro. Discharged: On glargine, metformin and sitagliptin, which was further simplified to only metformin. | In hospital: Hydration, insulin infusion, transitioning to subcutaneous basal bolus of insulin. Discharged: On glargine and metformin, which was further simplified to only metformin. |

| HbA1c (%) (postdischarge) | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | 6.7 (after ~7 weeks) | 5.9 (after ~2 months) | Data unavailable in case report |

| Blood glucose levels (mg/dL) (postdischarge) | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | 73 (FBS) | 80–140 | <140 | Data unavailable in case report |

| Postdischarge C-peptide (normal range) | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | Data unavailable in case report | 3.65 ng/mL (1.10–4.40 ng/mL) | 1.45 ng/mL (1.10–4.40 ng/mL) | 6.02 ng/mL (1.10–4.40 ng/mL) | Data unavailable in case report |

| Study origin | UK | UK | UK | USA | USA | USA | USA |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samuel, S.M.; Varghese, E.; Triggle, C.R.; Büsselberg, D. COVID-19 Vaccines and Hyperglycemia—Is There a Need for Postvaccination Surveillance? Vaccines 2022, 10, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030454

Samuel SM, Varghese E, Triggle CR, Büsselberg D. COVID-19 Vaccines and Hyperglycemia—Is There a Need for Postvaccination Surveillance? Vaccines. 2022; 10(3):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030454

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamuel, Samson Mathews, Elizabeth Varghese, Chris R. Triggle, and Dietrich Büsselberg. 2022. "COVID-19 Vaccines and Hyperglycemia—Is There a Need for Postvaccination Surveillance?" Vaccines 10, no. 3: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030454

APA StyleSamuel, S. M., Varghese, E., Triggle, C. R., & Büsselberg, D. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccines and Hyperglycemia—Is There a Need for Postvaccination Surveillance? Vaccines, 10(3), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030454