Awareness, Acceptance, and Associated Factors of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine among Parents of Daughters in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Setting, Design, and Period

2.2. Sample Size Determination

2.3. Sampling Procedure

2.4. Measurement of Variables

2.5. Data Collection and Quality Assurance Procedures

2.6. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Factors Associated with the Acceptance of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine among Parents of Daughters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOR | Adjusted odd ratios |

| ETB | Ethiopian birr |

| GAVI | Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunization |

| HIV | Human immune virus |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| LMICs | Low- to middle-income countries |

| PPS | Probability proportional to sample size |

| SNNPR | Southern Nation Nationality People Regional State |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Science |

| SS | Systematic sampling |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| STI | Sexually transmitted illness |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| WCU | Wachemo University |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Cheung, T.; Lau, J.T.F.; Wang, J.Z.; Mo, P.K.H.; Ho, Y.S. Acceptability of HPV vaccines and associations with perceptions related to HPV and HPV vaccines among male baccalaureate students in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Destaw, A.; Yosef, T.; Bogale, B. Parents willingness to vaccinate their daughter against human papillomavirus and its associated factors in Bench-Sheko zone, southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereje, N.; Ashenafi, A.; Abera, A.; Melaku, E.; Yirgashewa, K.; Yitna, M.; Shewaye, S.; Fasil, T.; Yoseph, Y. Knowledge and acceptance of HPV vaccination and its associated factors among parents of daughters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Infect. Agents Cancer 2021, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, M.E.; Le, Y.C.L.; Fernández-Espada, N.; Calo, W.A.; Savas, L.S.; Vélez, C.; Aragon, A.P.; Colón-López, V. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among Puerto Rican mothers and daughters, 2010: A qualitative study. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, B.; Yuan, S.; Wu, B.; Gong, L. Awareness and attitude towards human papillomavirus and its vaccine among females with and without daughter(s) who participated in cervical cancer screening in Shenzhen, China. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.C.S.; Lee, A.; Ngai, K.L.K.; Chor, J.C.Y.; Chan, P.K.S. Knowledge, Attitude, Practice and Barriers on Vaccination against Human Papillomavirus Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study among Primary Care Physicians in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control A Guide to Essential Practice, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Makwe, C.C.; Anorlu, R.I. Knowledge of and attitude toward human papillomavirus infection and vaccines among female nurses at a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Int. J. Womens Health 2011, 3, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.; Vanya, V.; Bhagat, S.; Binu, V.S.; Shetty, J. Awareness and attitude towards human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine among medical students in a premier medical school in India. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, L.; Hammarstedt, L. Impact of HPV in Oropharyngeal Cancer. J. Oncol. 2011, 2011, 509036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, B.; Yuan, S.; Wu, B.; Gong, L. Inequalities in awareness and attitude towards HPV and its vaccine between local and migrant residents who participated in cervical cancer screening in Shenzhen, China. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 52, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunade, K.S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, J.Y.M.; Fung, T.K.F.; Leung, L.H.M. Social and cultural construction processes involved in HPV vaccine hesitancy among Chinese women: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meites, E.; Winer, R.L.; Newcomb, M.E.; Gorbach, P.M.; Querec, T.D.; Rudd, J.; Collins, T.; Lin, J.; Moore, J.; Remble, T.; et al. Vaccine effectiveness against prevalent anal and oral human papillomavirus infection among men who have sex with men—United States, 2016–2018. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsous, M.M.; Ali, A.A.; Al-Azzam, S.I.; Abdel Jalil, M.H.; Al-Obaidi, H.J.; Al-abbadi, E.I.; Hussain, Z.K.; Jirjees, F.J. Knowledge and awareness about human papillomavirus infection and its vaccination among women in Arab communities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamolratanakul, S.; Pitisuttithum, P. Human papillomavirus vaccine efficacy and effectiveness against cancer. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hviid, A.; Thorsen, N.M.; Thomsen, L.N.; Møller, F.T.; Wiwe, A.; Frisch, M.; Valentiner-Branth, P.; Rytter, D.; Mølbak, K. Human papillomavirus vaccination and all-cause morbidity in adolescent girls: A cohort study of absence from school due to illness. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2014: Risk and Opportunity—Managing Risk for Development. The World Bank. 2013. Available online: http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/978-0-8213-9903-3 (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Central Statistical Agency. Ethiopia Mini Demographic, and Health Survey (EMDHS); Central Statistical Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Report and Performance of Hadiya Zone Health Department 2020/2021; Hadiya Zone Health Department: Hossana, Southern Ethiopia, 2019.

- CSA. Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions at Wereda Level from 2014–2017. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 1, 90–118. [Google Scholar]

- Alene, T.; Atnafu, A.; Mekonnen, Z.A.; Minyihun, A. Acceptance of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and Associated Factors Among Parents of Daughters in Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 8519–8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.C.; Law, C.-K. Revisiting knowledge, attitudes, and practice (KAP) on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among female university students in Hong Kong. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunade, K.S.; Sunmonu, O.; Osanyin, G.E.; Oluwole, A.A. Knowledge and Acceptability of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among Women Attending the Gynaecological Outpatient Clinics of a University Teaching Hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 2017, 8586459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaresmi, M.N.; Rozanti, N.M.; Simangunsong, L.B.; Wahab, A. Improvement of Parent’s awareness, knowledge, perception, and acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination after a structured-educational intervention. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezenwa, B.N.; Balogun, M.R.; Okafor, I.P. Mothers’ human papillomavirus knowledge and willingness to vaccinate their adolescent daughters in Lagos, Nigeria. Int. J. Womens Health 2013, 5, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.S.; Skrastins, E.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Jindal, P.; Oneko, O.; Yeates, K.; Booth, C.M.; Carpenter, J.; Aronson, K.J. Cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccine acceptability among rural and urban women in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e005828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalani, F.F.M.; Rani, M.D.M.; Isahak, I.; Aris, M.S.M.; Roslan, N. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination among Secondary School Students in Rural Areas of Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Int. J. Collab. Res. Intern. Med. Public Health 2016, 8, 420–434. [Google Scholar]

- Africa, S. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among academics at the University of KwaZulu- Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among academics at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2015, 57, 318–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ezat, S.W.P.; Hod, R.; Mustafa, J.; Hatta, A.Z.; Dali, M.; Sulaiman, A.S.; Azman, A. National HPV Immunisation Programme: Knowledge and Acceptance of Mothers Attending an Obstetrics Clinic at a Teaching Hospital, Kuala Lumpur. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 2991–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Variables | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 207 (39.1) |

| Female | 323 (60.9) | |

| Age in years | 18–29 | 80 (15.1) |

| 30 to 39 | 323 (60.9) | |

| ≥40 | 127 (24) | |

| Residence | Rural | 176 (33.2) |

| Urban | 354 (66.8) | |

| What is your marital status now? | Single | 69 (13) |

| Married | 437 (82.5) | |

| Never married | 24 (4.5) | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 86 (16.2) |

| Muslim | 64 (12.1) | |

| Protestant | 365 (68.9) | |

| Catholic | 15 (2.8) | |

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 16 (3) |

| Primary and secondary education | 96 (18.1) | |

| Certificate | 32 (6) | |

| Diploma | 64 (12.1) | |

| Degree and above | 322 (60.8) | |

| Occupation | Civil servant | 354 (66.8) |

| Self-employed | 80 (15.1) | |

| Merchant | 80 (15.1) | |

| Housewife | 16 (3) | |

| Ethnicity | Hadiya | 389 (73.4) |

| Kembata | 50 (9.4) | |

| Amhara | 8 (1.5) | |

| Tigre | 16 (2.1) | |

| Gurage | 10 (1.9) | |

| Oromo | 9 (1.7) | |

| Wolaita | 16 (3) | |

| Gurage | 32 (6) | |

| Silte | 16 (3) | |

| Others * | 41 (5.4) | |

| Number of daughters | One | 112 (21.1) |

| More than one | 418 (79.8) | |

| School type | Government School | 175 (33) |

| Private school | 355 (67) | |

| Information about HPV infection | Yes | 318 (60) |

| No | 212 (40) | |

| Sources of information about HPV infection (more than one possible answer possible) | TV or Radio | 144 (45.3) |

| Health workers | 78 (24.5) | |

| Their friend | 70 (22) | |

| Others ** | 26 (8.2) | |

| Monthly income | ≤ETB 4999 (≤USD 95.24) | 239 (45.1) |

| >ETB 4999 (>USD 95.24) | 291 (54.9) |

| Variables | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever heard about cervical cancer? | Yes | 418 (78.9) |

| No | 112 (21.1) | |

| Does cervical cancer only occur in females? | Yes | 499 (94.2) |

| No | 31 (5.8) | |

| Cervical cancer at an early stage produces no signs or symptoms | Yes | 111 (20.9) |

| No | 419 (79.1) | |

| Cervical cancer is a fast-growing cancer | Yes | 144 (27.2) |

| No | 386 (72.8) | |

| If detected early, is cervical cancer curable? | Yes | 418 (78.9) |

| No | 112 (21.9) | |

| Getting a Pap test helps early detection of cervical cancer | Yes | 371 (70) |

| No | 159 (30) | |

| Human papillomavirus is the main cause of cervical cancer | Yes | 387 (73) |

| No | 143 (27) | |

| Human papillomavirus is very common in women younger than 30 years | Yes | 435 (82.1) |

| No | 95 (17.9) | |

| Human papillomavirus vaccination is available for girls aged 9 to 14 years | Yes | 419 (79.1) |

| No | 111 (20.9) | |

| Cervical cancer risk can be reduced by HPV vaccination | Yes | 434 (81.9) |

| No | 96 (18.1) | |

| Do you know that HPV vaccination should be received before sexual debut? | Yes | 338 (63.8) |

| No | 192 (36.7) | |

| Do you know that HPV infection is a sexually transmitted infection? | Yes | 307 (57.9) |

| No | 223 (42.1) | |

| Do you know that the persistent infection of high-risk HPV could lead to cervical cancer? | Yes | 434 (81.9) |

| No | 96 (18.1) | |

| Do you know the symptoms of cervical cancer? | Yes | 386 (72.8) |

| No | 144 (27.2) | |

| Do you know the time duration that it takes for abnormal cervical cells to turn into cancerous cells? | Yes | 80 (15.1) |

| No | 450 (84.9) | |

| 70% of cervical cancer is caused by HPV types 16 and 18 | Yes | 112 (21.1) |

| No | 418 (78.9) | |

| Do you know the most common and effective treatment to cure cervical cancer? | Yes | 159 (30) |

| No | 371 (70) |

| Variables | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Are you willing to regularly consult a medical doctor for cervical cancer screening? | 175 | 33 | 16 | 3 | 48 | 9.1 | 291 | 54.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Those with multiple sex partners will be at higher risk for cervical cancer | 64 | 12.1 | 15 | 2.8 | 64 | 12.1 | 371 | 70 | 16 | 3 |

| Long-term use of contraceptive pills could cause cervical cancer | 112 | 21.1 | 296 | 55.8 | 5 | 0.9 | 90 | 17 | 27 | 5.1 |

| The use of condoms could reduce the risk of cervical cancer | 16 | 3 | 15 | 2.8 | 80 | 15.1 | 64 | 12.1 | 355 | 67 |

| HPV vaccination can prevent cervical cancers | 48 | 9.1 | 32 | 6 | 64 | 12.1 | 80 | 15.1 | 306 | 57.7 |

| Will you consult a medical doctor in case of abnormal bleeding between menstrual periods? | 274 | 51.7 | 16 | 3 | 80 | 15.1 | 80 | 15.1 | 80 | 15.1 |

| Regular Pap smear test helps early detection of cervical cancer | 16 | 3 | 16 | 3 | 15 | 2.8 | 355 | 67 | 128 | 24.2 |

| Are you willing to get a Pap smear test? | 32 | 6 | 32 | 6 | 32 | 6 | 111 | 20.9 | 323 | 60.9 |

| Are you willing to pay for a Pap smear test? | 64 | 12.1 | 64 | 12.1 | 339 | 64 | 32 | 6 | 31 | 5.8 |

| Government should provide free screening programs to reduce cervical cancer prevalence | 32 | 6 | 31 | 5.8 | 7 | 1.3 | 364 | 68.7 | 96 | 18.1 |

| The HPV vaccine might cause short-term problems, like fever or discomfort | 16 | 3 | 32 | 6 | 386 | 72.8 | 48 | 9.1 | 48 | 9.1 |

| Variables | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Heard of HPV | Yes | 467 (88.1) |

| No | 63 (11.9) | |

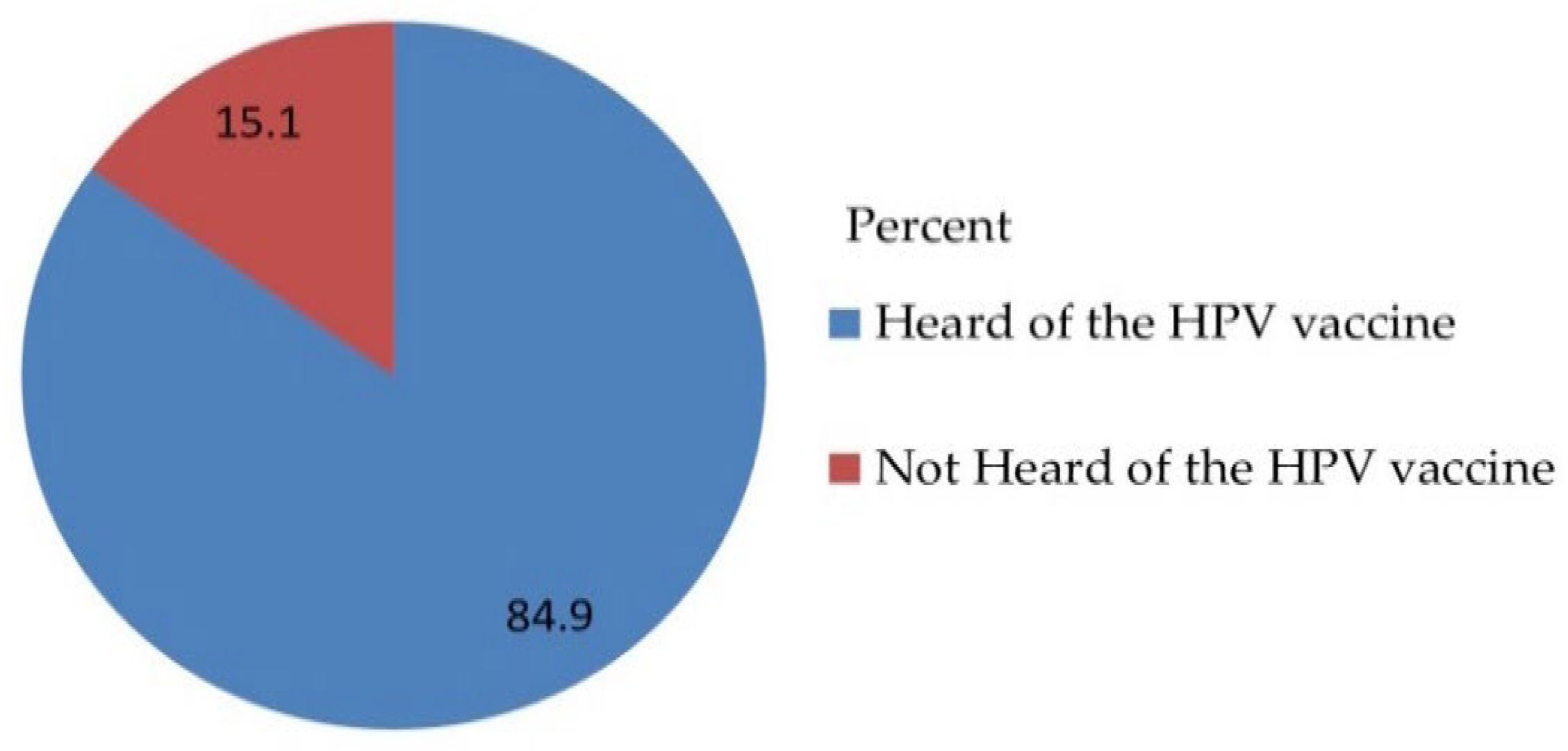

| Heard of the HPV vaccine | Yes | 450 (84.9) |

| No | 80 (15.1) | |

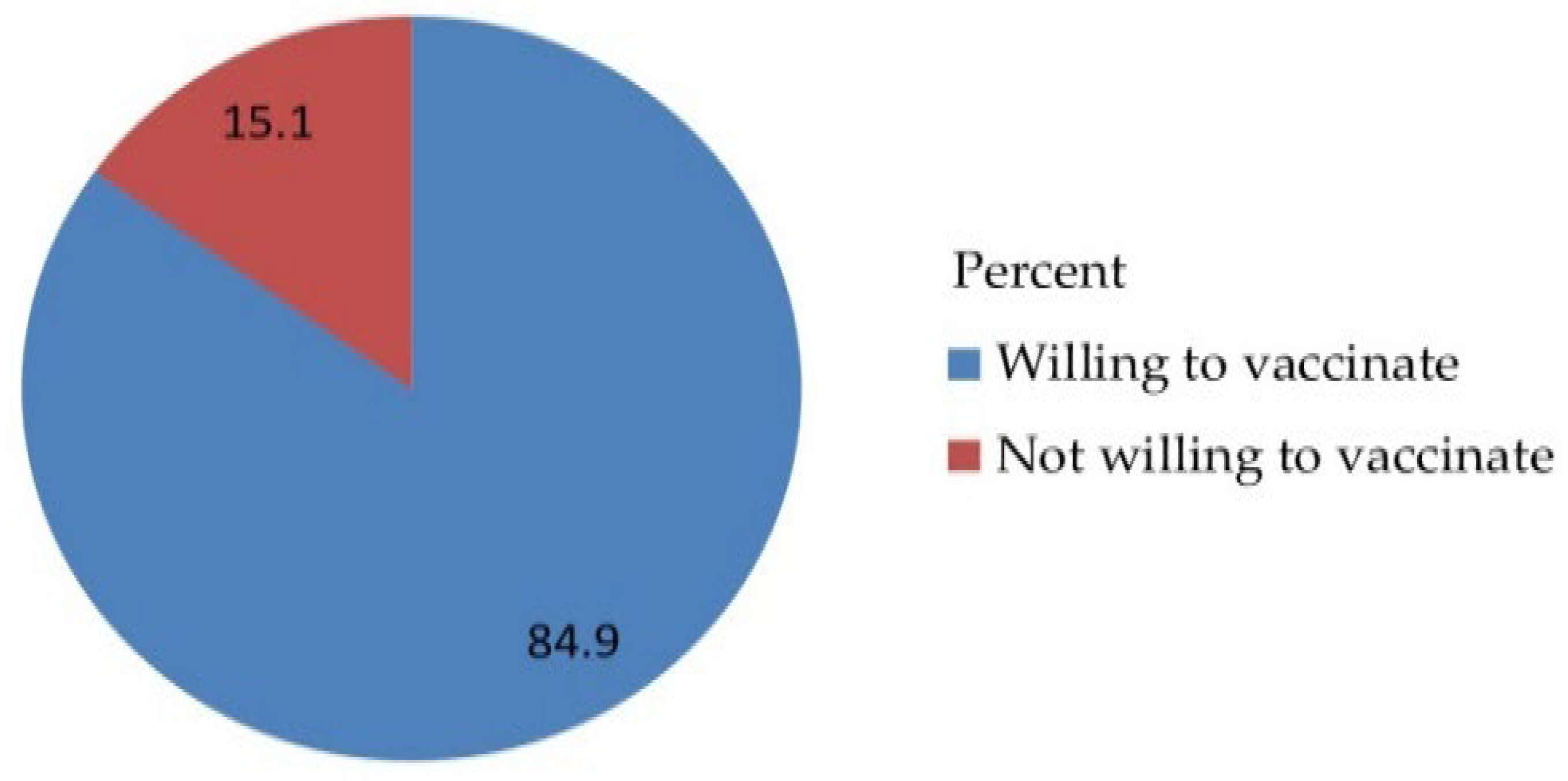

| Are you willing to vaccinate your daughter for HPV? | Yes | 450 (84.9) |

| No | 80 (15.1) | |

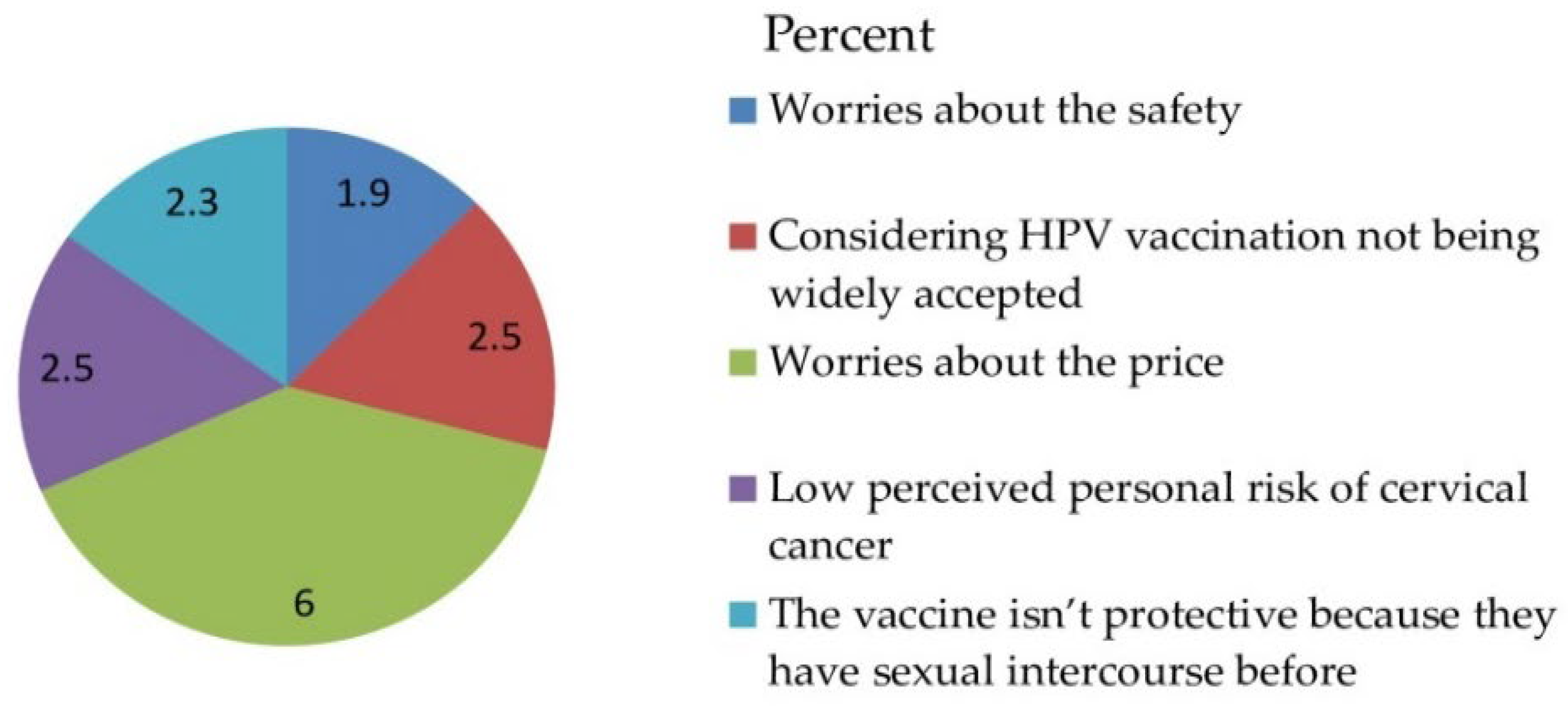

| The reasons for being unwilling to take the HPV vaccine (more than one possible answer possible (obstacles)) | Worried about the safety | 10 (1.9) |

| Considers HPV vaccination not widely accepted | 13 (2.5) | |

| Worried about the price | 32 (6) | |

| Low perceived personal risk of cervical cancer | 13 (2.5) | |

| The vaccine is not protective because they have had sexual intercourse before | 12 (2.3) | |

| Accept that they pay for HPV vaccination by themselves | Yes | 48 (9.1) |

| No | 482 (90.9) |

| Variable | Acceptability of the HPV Vaccination | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | p-Value | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 48 (60) | 159 (35.3) | 0.364 (0.224, 0.539) | 0.407 (0.221, 0.748) * | 0.004 |

| Female | 32 (40) | 291 (64.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Number of daughters | |||||

| One | 32 (40) | 80 (17.8) | 0.324 (0.195, 0.539) | 2.122 (1.221,3.685) * | 0.008 |

| More than one | 48 (60) | 370 (82.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| School type | |||||

| Government School | 48 (60) | 127 (28.2) | 0.262 (0.160, 0.429) | 0.476 (0.263, 0.861) * | 0.014 |

| Private school | 32 (40) | 323 (71.8) | 1 | 1 | |

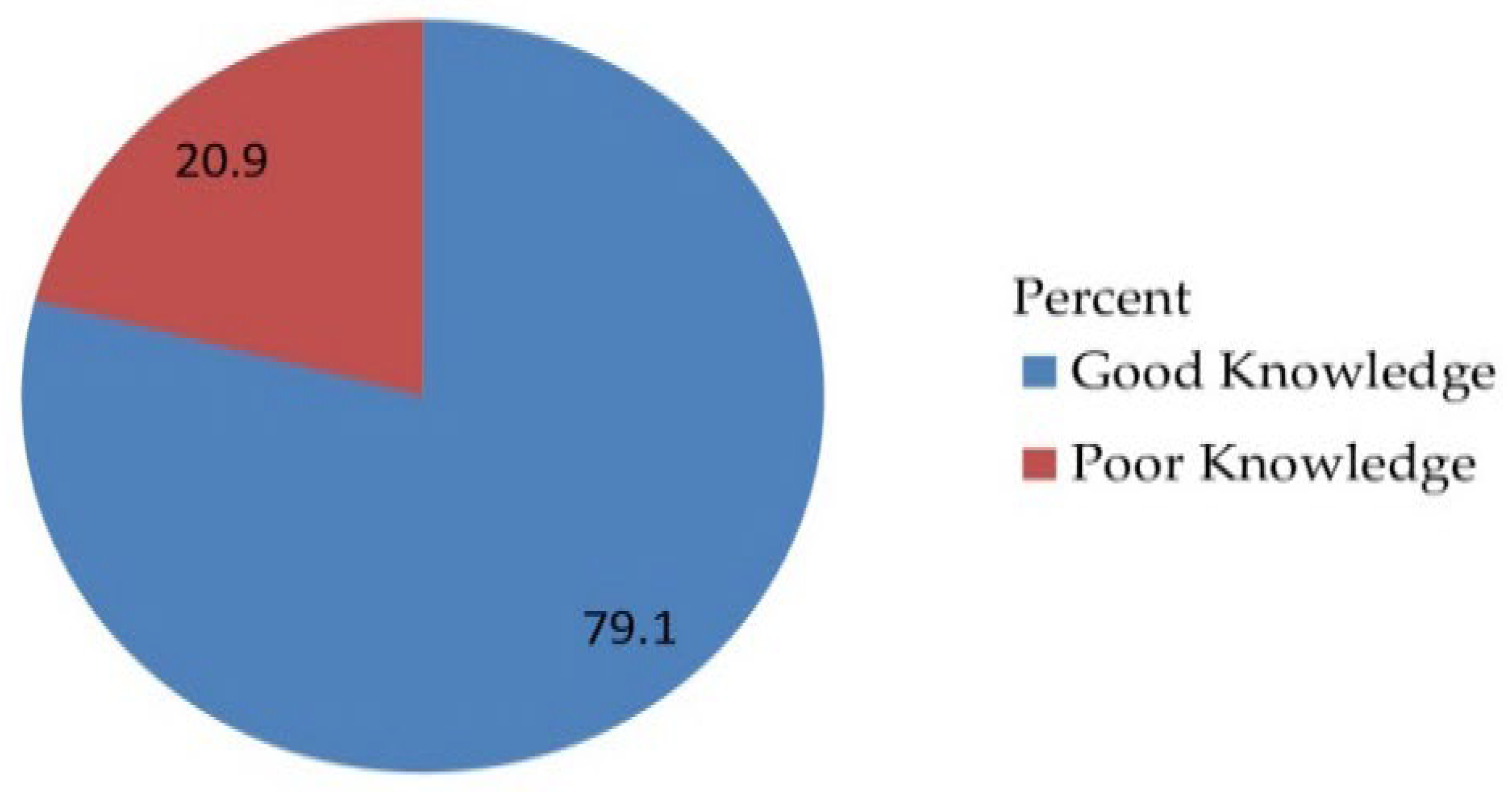

| Knowledge | |||||

| Poor knowledge | 32 (40) | 79 (17.6) | 0.319 (0.192, 0.531) | 0.532 (0.293, 0.969) * | 0.039 |

| Good knowledge | 48 (60) | 371 (82.4) | 1 | 1 | |

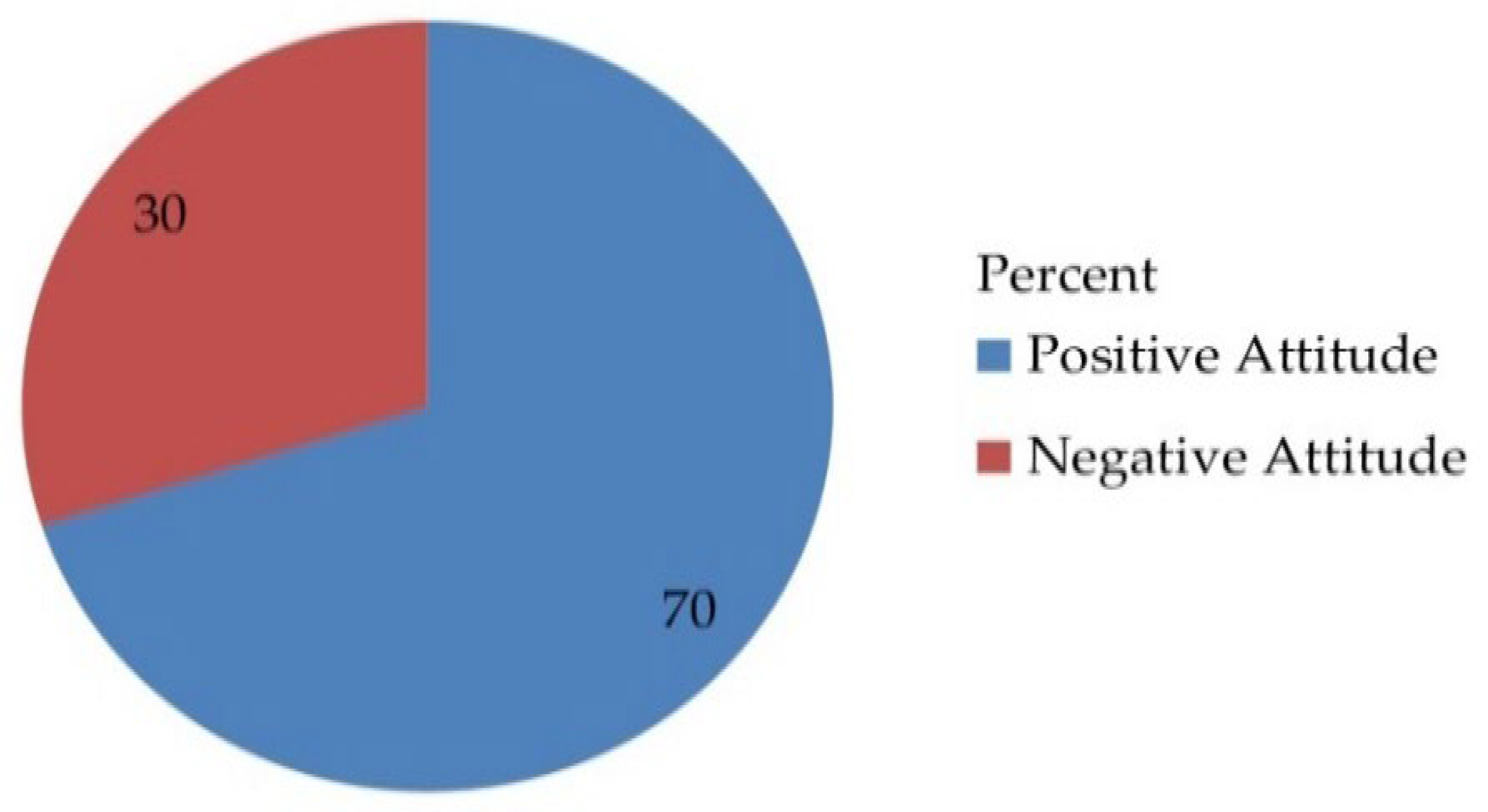

| Attitude | |||||

| Negative Attitude | 32 (40) | 127 (28.2) | 0.590 (0.361, 0.965) | 0.540 (0.299, 0.977) * | 0.042 |

| Positive Attitude | 48 (60) | 323 (71.8) | 1 | 1 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Larebo, Y.M.; Elilo, L.T.; Abame, D.E.; Akiso, D.E.; Bawore, S.G.; Anshebo, A.A.; Gopalan, N. Awareness, Acceptance, and Associated Factors of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine among Parents of Daughters in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1988. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10121988

Larebo YM, Elilo LT, Abame DE, Akiso DE, Bawore SG, Anshebo AA, Gopalan N. Awareness, Acceptance, and Associated Factors of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine among Parents of Daughters in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2022; 10(12):1988. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10121988

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarebo, Yilma Markos, Legesse Tesfaye Elilo, Desta Erkalo Abame, Denebo Ersulo Akiso, Solomon Gebre Bawore, Abebe Alemu Anshebo, and Natarajan Gopalan. 2022. "Awareness, Acceptance, and Associated Factors of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine among Parents of Daughters in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Vaccines 10, no. 12: 1988. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10121988

APA StyleLarebo, Y. M., Elilo, L. T., Abame, D. E., Akiso, D. E., Bawore, S. G., Anshebo, A. A., & Gopalan, N. (2022). Awareness, Acceptance, and Associated Factors of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine among Parents of Daughters in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines, 10(12), 1988. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10121988