Functional Ingredients from Agri-Food Waste: Effect of Inclusion Thereof on Phenolic Compound Content and Bioaccessibility in Bakery Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

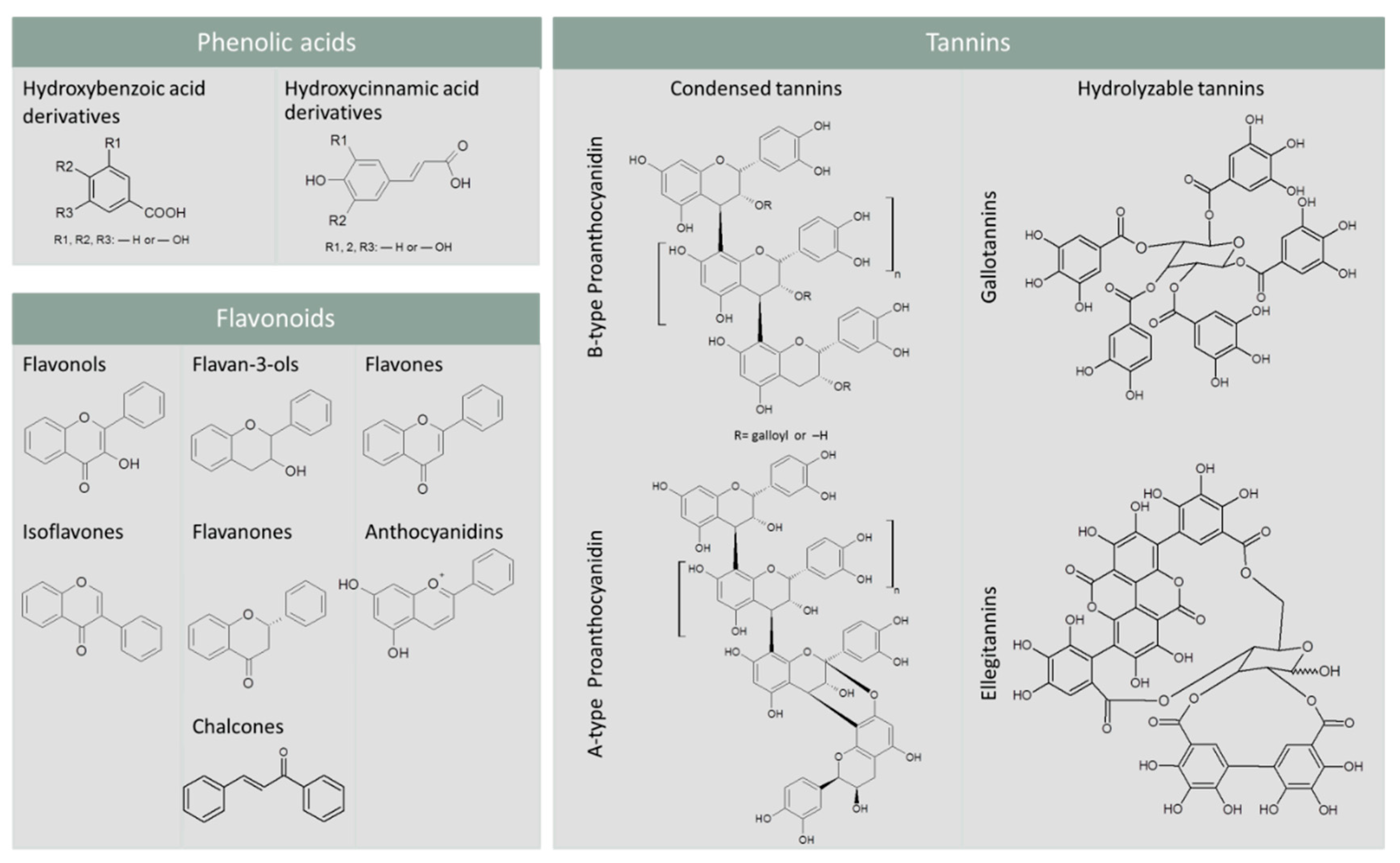

2. Dietary Phenolic Compounds: Classification, Biotransformation, and Health Benefits

3. Functional Ingredients from Agri-Food Waste: Recovery of Phenolic Compounds

3.1. Drying and Size Reduction Techniques

3.2. Extraction Methods

3.3. Fermentation and Enzymatic Treatments

4. Agri-Food Waste Contribution to Phenolic Compound Content and Antioxidant Capacity in Bakery Products

4.1. Fortification of Bakery Products by Functional Ingredients from Fruit and Vegetable Waste

4.1.1. Fruit Waste

4.1.2. Vegetable Waste

4.2. Fortification of Bakery Products by Functional Ingredients from Seed and Oilseed Crop Waste

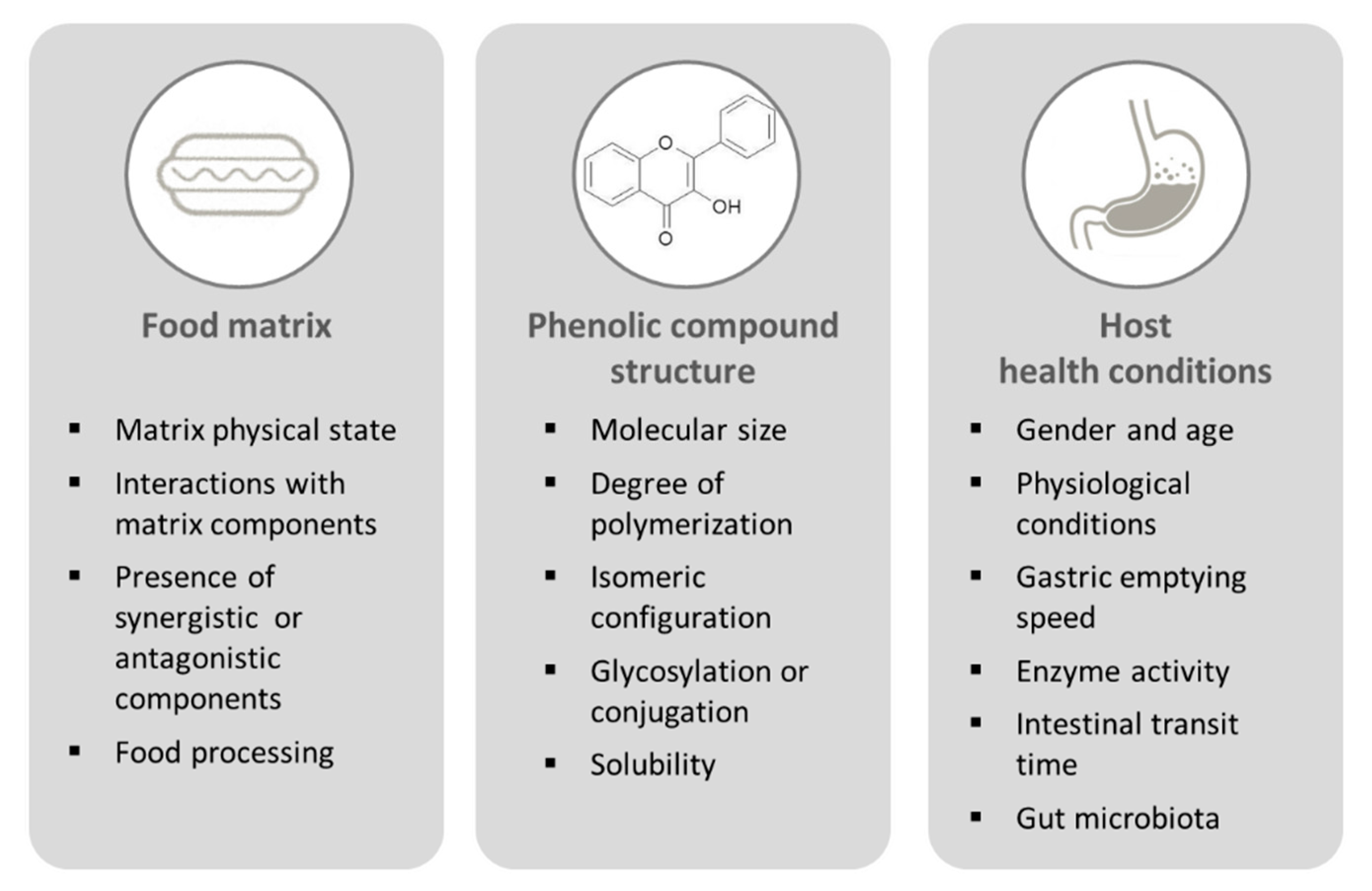

5. Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Phenolic Compounds in Bakery Products Enriched with Agri-Food Waste

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Sustainable Development Goals—Target 12.3. Available online: http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/indicators/1231/en/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Ben-Othman, S.; Jõudu, I.; Bhat, R. Bioactives from agri-food wastes: Present insights and future challenges. Molecules 2020, 25, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzella, L.; Moccia, F.; Nasti, R.; Marzorati, S.; Verotta, L.; Napolitano, A. Bioactive phenolic compounds from agri-food wastes: An update on green and sustainable extraction methodologies. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, W. Dietary polyphenols-important non-nutrients in the prevention of chronic noncommunicable diseases. A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. Sustainable Healthy Diets—Guiding Principles; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, M.; Skendi, A. Introduction to cereal processing and by-products. In Sustainable Recovery and Reutilization of Cereal Processing By-Products; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–25. ISBN 9780081022146. [Google Scholar]

- Melini, V.; Melini, F.; Acquistucci, R. Phenolic compounds and bioaccessibility thereof in functional pasta. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Martinez, M.M. Fruit and vegetable by-products as novel ingredients to improve the nutritional quality of baked goods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2119–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, Z.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I. Food industry by-products used as functional ingredients of bakery products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheynier, V.; Comte, G.; Davies, K.M.; Lattanzio, V.; Martens, S. Plant phenolics: Recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, and ecophysiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 72, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Varatharajan, V.; Oh, W.Y.; Peng, H. Phenolic compounds in agri-food by-products, their bioavailability and health effects. J. Food Bioact. 2019, 5, 57–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Brandão, E.; Guerreiro, C.; Soares, S.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Tannins in food: Insights into the molecular perception of astringency and bitter taste. Molecules 2020, 25, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarowicz, R.; Janiak, M. Hydrolysable tannins. In Encyclopedia of Food Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 337–343. ISBN 9780128140451. [Google Scholar]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhova, V.A.; Chegodaev, Y.S.; Wu, W.K.; Orekhov, A.N. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in atherosclerosis development and treatment. Biology 2020, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Tew, K.D. Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, T.; Ziegler, A.C.; Dimitrion, P.; Zuo, L. Oxidative Stress in neurodegenerative diseases: From molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renaud, J.; Martinoli, M.G. Considerations for the use of polyphenols as therapies in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Nutraceutical and Functional Food Components, 1st ed.; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier—Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stenmarck, Å.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G.; Bukst, M.; Cseh, B.; Juul, S.; Parry, A.; Politano, A.; Redlingshofer, B.; et al. FUSIONS: Estimates of European Food Waste Levels; IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.T. Potential, uses and future perspectives of agricultural wastes. In Recovering Bioactive Compounds from Agricultural Wastes; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vega, R.; Oomah, B.D.; Vergara-Castañeda, H.A. Food Wastes And By-Products: Nutraceutical and Health Potential; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781119534105. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, B.; Bansal, N.; Zhang, M.; Schuck, P. Handbook of Food Powders: Processes and Properties; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Sawston, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780857098672. [Google Scholar]

- Bas-Bellver, C.; Barrera, C.; Betoret, N.; Seguí, L. Turning agri-food cooperative vegetable residues into functional powdered ingredients for the food industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, C. Freeze drying for food powder production. In Handbook of Food Powders: Processes and Properties; Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 57–84. ISBN 9780857098672. [Google Scholar]

- Michalska, A.; Wojdyło, A.; Lech, K.; Łysiak, G.P.; Figiel, A. Effect of different drying techniques on physical properties, total polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of blackcurrant pomace powders. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 78, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglund, E.; Eliasson, L.; Oliveira, G.; Almli, V.L.; Sozer, N.; Alminger, M. Effect of drying and extrusion processing on physical and nutritional characteristics of bilberry press cake extrudates. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 92, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Torres, C.; Díaz-Maroto, M.C.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Pérez-Coello, M.S. Effect of freeze-drying and oven-drying on volatiles and phenolics composition of grape skin. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 660, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struck, S.; Rohm, H. Fruit processing by-products as food ingredients. In Valorization of Fruit Processing By-Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska, M.; Michalska, A. Microwave-assisted drying of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) fruits: Drying kinetics, polyphenols, anthocyanins, antioxidant capacity, colour and texture. Food Chem. 2016, 212, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.D.; Khan, M.I.H.; Karim, M.A. A mathematical model for predicting the transport process and quality changes during intermittent microwave convective drying. Food Chem. 2020, 325, 126932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, E.M.; House, A.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Chatzifragkou, A. Effect of dehydration on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) pomace. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Gou, M.; Xia, T.; Li, W.; Song, X.; Jiang, H. Characteristics of pitaya after radio frequency treating: Structure, phenolic compounds, antioxidant, and antiproliferative activity. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horuz, E.; Bozkurt, H.; Karataş, H.; Maskan, M. Effects of hybrid (microwave-convectional) and convectional drying on drying kinetics, total phenolics, antioxidant capacity, vitamin C, color and rehydration capacity of sour cherries. Food Chem. 2017, 230, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, F.M.; Yüksekkaya, S.; Vardin, H.; Karaaslan, M. The effects of drying conditions on moisture transfer and quality of pomegranate fruit leather (pestil). J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2017, 16, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V.; Yadav, B.S.; Yadav, R.B.; Nema, P.K. Effect of osmotic agents and ultasonication on osmo-convective drying of sweet lime (Citrus limetta) peel. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venskutonis, P.R. Berries. In Valorization of Fruit Processing By-Products; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier—Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis, C.M. Food Waste Recovery: Processing Technologies and Industrial Techniques; Elsevier—Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780128004197. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, V.; Vyas, P.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Food waste: A potential bioresource for extraction of nutraceuticals and bioactive compounds. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinela, J.; Prieto, M.A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Carvalho, A.M.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Curran, T.P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Valorisation of tomato wastes for development of nutrient-rich antioxidant ingredients: A sustainable approach towards the needs of the today’s society. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 41, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trasanidou, D.; Apostolakis, A.; Makris, D.P. Development of a green process for the preparation of antioxidant and pigment-enriched extracts from winery solid wastes using response surface methodology and kinetics. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2016, 203, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosou, C.; Kyriakopoulou, K.; Bimpilas, A.; Tsimogiannis, D.; Krokida, M. A comparative study on different extraction techniques to recover red grape pomace polyphenols from vinification byproducts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 75, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosiljkov, T.; Dujmić, F.; Cvjetko Bubalo, M.; Hribar, J.; Vidrih, R.; Brnčić, M.; Zlatic, E.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Jokić, S. Natural deep eutectic solvents and ultrasound-assisted extraction: Green approaches for extraction of wine lees anthocyanins. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babazadeh, A.; Taghvimi, A.; Hamishehkar, H.; Tabibiazar, M. Development of new ultrasonic–solvent assisted method for determination of trans-resveratrol from red grapes: Optimization, characterization, and antioxidant activity (ORAC assay). Food Biosci. 2017, 20, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratoglou, E.; Malliou, V.; Makris, D.P. Novel glycerol-based natural eutectic mixtures and their efficiency in the ultrasound-assisted extraction of antioxidant polyphenols from agri-food waste biomass. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2016, 7, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, M.; Śliwa, K.; Sikora, E.; Ogonowski, J.; Oszmiański, J.; Kolniak-Ostek, J. Ultrasound-assisted and micelle-mediated extraction as a method to isolate valuable active compounds from apple pomace. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavins, L.; Kviesis, J.; Nakurte, I.; Klavins, M. Berry press residues as a valuable source of polyphenolics: Extraction optimisation and analysis. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 93, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, K.; Pristijono, P.; Golding, J.B.; Stathopoulos, C.E.; Bowyer, M.C.; Scarlett, C.J.; Vuong, Q.V. Screening the effect of four ultrasound-assisted extraction parameters on hesperidin and phenolic acid content of aqueous citrus pomace extracts. Food Biosci. 2018, 21, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodsamran, P.; Sothornvit, R. Extraction of phenolic compounds from lime peel waste using ultrasonic-assisted and microwave-assisted extractions. Food Biosci. 2019, 28, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; de los, Á.; Espino, M.; Gomez, F.J.V.; Silva, M.F. Novel approaches mediated by tailor-made green solvents for the extraction of phenolic compounds from agro-food industrial by-products. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 671–678. [Google Scholar]

- Katsampa, P.; Valsamedou, E.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. A green ultrasound-assisted extraction process for the recovery of antioxidant polyphenols and pigments from onion solid wastes using Box-Behnken experimental design and kinetics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riciputi, Y.; Diaz-de-Cerio, E.; Akyol, H.; Capanoglu, E.; Cerretani, L.; Caboni, M.F.; Verardo, V. Establishment of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from industrial potato by-products using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2018, 269, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agcam, E.; Akyıldız, A.; Balasubramaniam, V.M. Optimization of anthocyanins extraction from black carrot pomace with thermosonication. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, N.; Thakur, S.; Kaur, A. Ultrasound assisted extraction of polyphenols and their distribution in whole mung bean, hull and cotyledon. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharajan, V.; Shanmugam, S.; Ramaswamy, A. Model generation and process optimization of microwave-assisted aqueous extraction of anthocyanins from grape juice waste. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, e12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Dahuja, A.; Sachdev, A.; Kaur, C.; Varghese, E.; Saha, S.; Sairam, K.V.S.S. Valorisation of black carrot pomace: Microwave assisted extraction of bioactive phytoceuticals and antioxidant activity using Box–Behnken design. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda Meija, J.A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Versari, A.; Conidi, C.; Cassano, A. Microwave-assisted extraction and membrane-based separation of biophenols from red wine lees. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 117, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurmanović, S.; Jug, M.; Safner, T.; Radić, K.; Domijan, A.-M.; Pedisić, S.; Šimić, S.; Jablan, J.; Čepo, D.V. Utilization of olive pomace as a source of polyphenols: Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction and characterization of spray-dried extract. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 58, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Manna, L.; Bugnone, C.A.; Banchero, M. Valorization of hazelnut, coffee and grape wastes through supercritical fluid extraction of triglycerides and polyphenols. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 104, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrentino, G.; Morozova, K.; Mosibo, O.K.; Ramezani, M.; Scampicchio, M. Biorecovery of antioxidants from apple pomace by supercritical fluid extraction. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Pardo, F.A.; Nakajima, V.M.; Macedo, G.A.; Macedo, J.A.; Martínez, J. Extraction of phenolic compounds from dry and fermented orange pomace using supercritical CO2 and cosolvents. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 101, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, J.; Storer Samaniego, C.; Wang, L.; Burrows, L.; Tucker, E.; Dwarshuis, N.; Ammerman, M.; Zand, A. Antioxidant potential of Juglans nigra, black walnut, husks extracted using supercritical carbon dioxide with an ethanol modifier. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsea, M.; Stefou, I.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P. Screening of natural sodium acetate-based low-transition temperature mixtures (LTTMs) for enhanced extraction of antioxidants and pigments from red vinification solid wastes. Environ. Process. 2017, 4, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radošević, K.; Ćurko, N.; Gaurina Srček, V.; Cvjetko Bubalo, M.; Tomašević, M.; Kovačević Ganić, K.; Radojčić Redovniković, I. Natural deep eutectic solvents as beneficial extractants for enhancement of plant extracts bioactivity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefou, I.; Grigorakis, S.; Loupassaki, S.; Makris, D.P. Development of sodium propionate-based deep eutectic solvents for polyphenol extraction from onion solid wastes. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanioti, S.; Tzia, C. Extraction of phenolic compounds from olive pomace by using natural deep eutectic solvents and innovative extraction techniques. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 48, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakroun, D.; Grigorakis, S.; Loupassaki, S.; Makris, D.P. Enhanced-performance extraction of olive (Olea europaea) leaf polyphenols using L-lactic acid/ammonium acetate deep eutectic solvent combined with β-cyclodextrin: Screening, optimisation, temperature effects and stability. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alañón, M.E.; Ivanović, M.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. Choline chloride derivative-based deep eutectic liquids as novel green alternative solvents for extraction of phenolic compounds from olive leaf. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 1685–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadh, P.K.; Kumar, S.; Chawla, P.; Singh Duhan, J. Fermentation: A boon for production of bioactive compounds by processing of food industries wastes (by-products). Molecules 2018, 10, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulf, F.V.; Vodnar, D.C.; Dulf, E.H.; Pintea, A. Phenolic compounds, flavonoids, lipids and antioxidant potential of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) pomace fermented by two filamentous fungal strains in solid state system. Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulf, F.V.; Vodnar, D.C.; Dulf, E.H.; Toşa, M.I. Total phenolic contents, antioxidant activities, and lipid fractions from berry pomaces obtained by solid-state fermentation of two sambucus species with aspergillus niger. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3489–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, A.S.C.; Chávez, D.W.H.; Oliveira, R.A.; Bon, E.P.S.; Terzi, S.C.; Souza, E.F.; Gottschalk, L.M.F.; Tonon, R.V. Use of grape pomace for the production of hydrolytic enzymes by solid-state fermentation and recovery of its bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joginder, S.D.; Kamal, M.; Pardeep, K.S.; Pooja, S. Surekha Bio-enrichment of phenolics and free radicals scavenging activity of wheat (WH-711) fractions by solid state fermentation with Aspergillus oryzae. African J. Biochem. Res. 2016, 10, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arte, E.; Rizzello, C.G.; Verni, M.; Nordlund, E.; Katina, K.; Coda, R. Impact of enzymatic and microbial bioprocessing on protein modification and nutritional properties of wheat bran. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8685–8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, R.; Castro-López, C.; Sánchez-Alejo, E.J.; Niño-Medina, G.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G. Phenolic compound recovery from grape fruit and by- products: An overview of extraction methods. In Grape and Wine Biotechnology; InTech: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, I.M.; Roberto, B.S.; Blumberg, J.B.; Chen, C.Y.O.; Macedo, G.A. Enzymatic biotransformation of polyphenolics increases antioxidant activity of red and white grape pomace. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-García, R.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G.; Aguilar, C.N. Enzyme-assisted extraction of antioxidative phenolics from grape (Vitis vinifera L.) residues. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ghandahari Yazdi, A.P.; Barzegar, M.; Sahari, M.A.; Ahmadi Gavlighi, H. Optimization of the enzyme-assisted aqueous extraction of phenolic compounds from pistachio green hull. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, M.; Sultana, B.; Akram, S.; Adnan, A.; Owusu-Apenten, R.; Nigam Singh, P. Enzyme-assisted extraction of polyphenols from pomegranate (Punica granatum) peel. Res. Rev. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 5, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, K.; Akhtar, S.; Ismail, T. Nutritional and organoleptic evaluation of functional bread prepared from raw and processed defatted mango kernel flour. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obafaye, R.O.; Omoba, O.S. Orange peel flour: A potential source of antioxidant and dietary fiber in pearl-millet biscuit. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourekoua, H.; Różyło, R.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Benatallah, L.; Zidoune, M.N.; Dziki, D. Pomegranate seed powder as a functional component of gluten-free bread (Physical, sensorial and antioxidant evaluation). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1906–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Food and Agriculture Data—FAOSTAT. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Talekar, S.; Patti, A.F.; Singh, R.; Vijayraghavan, R.; Arora, A. From waste to wealth: High recovery of nutraceuticals from pomegranate seed waste using a green extraction process. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Bianco, A.M.; Paradiso, V.M.; Summo, C.; Gambacorta, G.; Caponio, F. Physico-chemical, sensory and volatile profiles of biscuits enriched with grape marc extract. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, V.; Christiano, F.D.P.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Tessaro, I.C.; Thys, R.C.S. The effect of the incorporation of grape marc powder in fettuccini pasta properties. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 58, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, V.; Padalino, L.; Nardiello, D.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. New approach to enrich pasta with polyphenols from grape marc. J. Chem. 2015, 2015, 734578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, V.; Padalino, L.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Briviba, K. Red grape marc flour as food ingredient in durum wheat spaghetti: Nutritional evaluation and bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2018, 24, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazzotta, S.; Sillani, S.; Manzocco, L. Exploitation of lettuce waste flour to increase bread functionality: Effect on physical, nutritional, sensory properties and on consumer response. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 2290–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Gallagher, E.; Bademunt, A.; Viñas, I.; Bobo, G.; Villaró, S.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Bioaccessibility, physicochemical, sensorial, and nutritional characteristics of bread containing broccoli co-products. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabińska, N.; Ciska, E.; Szmatowicz, B.; Krupa-Kozak, U. Broccoli by-products improve the nutraceutical potential of gluten-free mini sponge cakes. Food Chem. 2018, 267, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Lim, S. Bin Antioxidant and anticancer activities of broccoli by-products from different cultivars and maturity stages at harvest. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 20, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anal, A.K. Food processing by-products and their utilization: Introduction. In Food Processing By-Products and Their Utilization; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- El Mashad, H.M.; Zhang, R.; Pan, Z. Onion and garlic. In Integrated Processing Technologies for Food and Agricultural By-Products; Pan, Z., Zhang, R., Zicari, S., Eds.; Elsevier—Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 273–296. ISBN 9780128141397. [Google Scholar]

- Prokopov, T.; Chonova, V.; Slavov, A.; Dessev, T.; Dimitrov, N.; Petkova, N. Effects on the quality and health-enhancing properties of industrial onion waste powder on bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 5091–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowiak, T.; Grzelak-Błaszczyk, K.; Bonikowski, R.; Balawejder, M. Optimization of extraction process of antioxidant compounds from yellow onion skin and their use in functional bread production. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 117, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Sustainable Recovery and Reutilization of Cereal Processing By-Products; Elsevier—Woodhead Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 978-0-08-102162-0. [Google Scholar]

- Duţă, D.E.; Culeţu, A.; Mohan, G. Reutilization of cereal processing by-products in bread making. In Sustainable Recovery and Reutilization of Cereal Processing By-Products; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier—Woodhead Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 279–317. ISBN 9780081022146. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualone, A.; Delvecchio, L.N.; Gambacorta, G.; Laddomada, B.; Urso, V.; Mazzaglia, A.; Ruisi, P.; Di Miceli, G. Effect of supplementation with wheat bran aqueous extracts obtained by ultrasound-assisted technologies on the sensory properties and the antioxidant activity of dry pasta. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1739–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călinoiu, L.F.; Cătoi, A.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Solid-state yeast fermented wheat and oat bran as a route for delivery of antioxidants. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassoni, A.; Tedeschi, T.; Zurlini, C.; Cigognini, I.M.; Petrusan, J.-I.; Rodríguez, Ó.; Neri, S.; Celli, A.; Sisti, L.; Cinelli, P.; et al. State-of-the-art production chains for peas, beans and chickpeas—valorization of agro-industrial residues and applications of derived extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, D.; Alonso de Linaje, A.; Herrero, A.; Asensio-Vegas, C.; Miranda, J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; de Luis, D.A.; Martin-Diana, A.B. Carob by-products and seaweeds for the development of functional bread. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño-Medina, G.; Muy-Rangel, D.; de la Garza, A.; Rubio-Carrasco, W.; Pérez-Meza, B.; Araujo-Chapa, A.; Gutiérrez-Álvarez, K.; Urías-Orona, V. Dietary fiber from chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and soybean (Glycine max) husk byproducts as baking additives: Functional and nutritional properties. Molecules 2019, 24, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velioǧlu, S.D.; Güner, K.G.; Velioǧlu, H.M.; ÇelIkyurt, G. The use of hazelnut testa in bakery products. J. Tekirdag Agric. Fac. 2017, 14, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Klingel, T.; Kremer, J.I.; Gottstein, V.; Rajcic de Rezende, T.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. A Review of Coffee By-Products Including Leaf, Flower, Cherry, Husk, Silver Skin, and Spent Grounds as Novel Foods within the European Union. Foods 2020, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmetti, A.; Fernandez-Gomez, B.; Zeppa, G.; Del Castillo, M.D. Nutritional quality, potential health promoting properties and sensory perception of an improved gluten-free bread formulation containing inulin, rice protein and bioactive compounds extracted from coffee byproducts. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, K.H.N.; García, N.V.M.; Vega, R.C. Cocoa By-products. In Food Wastes and By-products; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 373–411. [Google Scholar]

- Jozinović, A.; Panak Balentić, J.; Ačkar, Đ.; Babić, J.; Pajin, B.; Miličević, B.; Guberac, S.; Vrdoljak, A.; Šubarić, D. Cocoa husk application in the enrichment of extruded snack products. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdybel, B.; Różyło, R.; Sagan, A. Use of a waste product from the pressing of chia seed oil in wheat and gluten-free bread processing. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedola, A.; Cardinali, A.; Alessandro, M.; Nobile, D.; Conte, A. Enrichment of bread with olive oil industrial by-product. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2019, 9, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cedola, A.; Cardinali, A.; D’Antuono, I.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. Cereal foods fortified with by-products from the olive oil industry. Food Biosci. 2020, 33, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, M.; Bleve, G.; Selvaggini, R.; Veneziani, G.; Servili, M.; Mita, G. Bioactive compounds and stability of a typical Italian bakery products “taralli” enriched with fermented olive paste. Molecules 2019, 24, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedola, A.; Palermo, C.; Centonze, D.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Characterization and Bio-Accessibility Evaluation of Olive Leaf Extract-Enriched “Taralli”. Foods 2020, 9, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchi, L.; Schuster, N.; Flynn, D.; Bechtel, R.; Bellumori, M.; Innocenti, M.; Mulinacci, N.; Guinard, J. Sensory profiling and consumer acceptance of pasta, bread, and granola bar fortified with dried olive pomace (pâté): A byproduct from virgin olive oil production. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 2995–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nunzio, M.; Picone, G.; Pasini, F.; Chiarello, E.; Caboni, M.F.; Capozzi, F.; Gianotti, A.; Bordoni, A. Olive oil by-product as functional ingredient in bakery products. Influence of processing and evaluation of biological effects. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 108940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colantuono, A.; Ferracane, R.; Vitaglione, P. Potential bioaccessibility and functionality of polyphenols and cynaropicrin from breads enriched with artichoke stem. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agri-Food Waste (AFW) | Functional Ingredient from AFW | AFW-Enriched Product | TPC (mg GAE 100 g−1 DM) and TFC (mg QE 100 g−1 DM) | Antioxidant Capacity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mango seed kernel (raw) | Powder/Flour | Bread added with raw mango seed kernel flour at a substitution level of 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25% (w/w) | TPC (control): 85.00 TPC (5%): 91.13 * TPC (10%): 100.15 TPC (15%): 112.59 TPC (20%): 119.70 TPC (25%): 128.35 | DPPH (control bread): 24.35 1 DPPH (5%): 27.35 1,* DPPH (10%): 29.71 1 DPPH (15%): 33.17 1 DPPH (20%): 37.82 1 DPPH (25%): 41.57 1 FRAP (control bread): 372.6 2 FRAP (5%): 387.4 2 FRAP (10%): 398.6 2 FRAP (15%): 412.4 2 FRAP (20%): 426.9 2 FRAP (25%): 441.4 2 | Amin et al. [81] |

| Mango seed kernel (processed defatted) | Powder/Flour | Bread added with processed defatted mango kernel flour at a substitution level of 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25% (w/w) | TPC (control): 85.00 TPC (5%): 88.39 * TPC (10%): 91.71 TPC (15%): 95.42 TPC (20%): 99.44 TPC (25%): 106.74 | DPPH (control bread): 24.35 1 DPPH (5%): 25.06 1,* DPPH (10%): 27.46 1,* DPPH (15%): 29.53 1 DPPH (20%): 33.49 1 DPPH (25%): 36.39 1 FRAP (control bread): 372.6 2 FRAP (5%): 379.3 2 FRAP (10%): 387.8 2 FRAP (15%): 395.8 2 FRAP (20%): 405.5 2 FRAP (25%): 420.1 2 | Amin et al. [81] |

| Orange peel | Powder/Flour | Biscuits added with orange peel flour at a substitution level of 5, 10, 15, and 20% (w/w) | TPC (control): 584 TPC (5%): 832 TPC (10%): 960 TPC (15%): 1032 TPC (20%): 1187 TFC (control): 120 TFC (5%): 334 TFC (10%): 627 TFC (15%): 784 TFC (20%): 812 | ABTS (control): 117 3 ABTS (5%): 148 3 ABTS (10%): 206 3 ABTS (15%): 219 3 ABTS (20%): 219 3 DPPH (control): 238 4 DPPH (5%): 211 4 DPPH (10%): 197 4 DPPH (15%): 192 4 DPPH (20%): 171 4 | Obafaye et al. [82] |

| Pomegranate seeds | Powder/Flour | GF bread added with pomegranate seed powder at a substitution level of 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10% (w/w) | TPC (control): 88 TPC (2.5%): 129 TPC (5%): 143 TPC (7.5%): 216 TPC (10%): 247 | DPPH (control): 25.97 5 DPPH (2.5%): 29.39 5,* DPPH (5%): 13.55 5 DPPH (7.5%): 14.24 5 DPPH (10%):11.97 5 ABTS (control): 9.95 5 ABTS (2.5%): 6.22 5 ABTS (5%l): 5.99 5 ABTS (7.5%): 5.16 5 ABTS (10%): 6.14 5 | Bourekoua et al. [83] |

| Grape marc | Extract | Biscuits added with grape marc extract (flour:grape marc extract ratio ≈ 2:1 g/mL) | TPC (control): 44 TPC (enriched): 62.9 TFC (control): 3.1 mg CE 100 g−1 DM TFC (enriched): 48.1 mg CE 100 g−1 DM Total anthocyanins (control): nd Total anthocyanins (enriched): 140 mg Mv-3-glcequ kg−1 Proanthocyanidins (control): nd Proanthocyanidins (enriched): 151 mg Cy-Clequ kg−1 | DPPH (control): 33.2 1 DPPH (enriched): 48.1 1 ABTS (control): 472 μmol TEAC kg−1 DM ABTS (enriched): 790 μmol TEAC kg−1 DM | Pasqualone et al. [86] |

| Lettuce waste | Powder/Flour | Wheat bread added with lettuce waste flour at a substitution level of 2, 4, 12, and 40% (w/w) | TPC (control): 43.55 TPC (2%): 58.56 TPC (4%): 73.12 TPC (12%): 135.45 TPC (20%): 340.62 | DPPH (control): 3873.3 6 DPPH (2%): 4486.7 6 DPPH (4%): 4644.4 6 DPPH (12%): 5602.2 6 DPPH (20%): 10290.0 6 | Plazzotta et al. [90] |

| Broccoli stems or leaves | Powder/Flour | Bread added with broccoli by-product powder (stems or leaves) at a substitution level of 2% (w/w) | TPC (control): ≈ 170 TPC (enriched, stems): ≈ 189 TPC (enriched, leaves): ≈184 | FRAP (control): ≈ 3.9 7 FRAP (enriched, stems): ≈ 4.6 7 FRAP (enriched, leaves):≈ 4.4 7 DPPH (control): ≈ 1.65 7 DPPH (enriched, stems):≈ 2.25 7 DPPH (enriched, leaves):≈ 2.31 7 | Lafarga et al. [91] |

| Broccoli leaves | Powder/Flour | GF mini sponge cakes added with broccoli leaf powder at a substitution level of 2.5, 5, and 7.5% (w/w) | TPC (control): 46 TPC (2.5%): 77 TPC (5%): 87 TPC (7.5%): 99 | ABTS (control): 115 3 ABTS (2.5%): 257 3 ABTS (5%): 322 3 ABTS (7.5%): 419 3 FRAP (control): 24 3 FRAP (2.5%): 104 3 FRAP (5%): 173 3 FRAP (7.5%): 277 3 | Drabińska et al. [92] |

| Onion (apical trimmings of the bulbs, and the outer dry and semidry layers) | Powder/Flour | Wheat bread added with industrial onion waste at a substitution level of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5% (w/w) | TPC (control): 49 TPC (1%): 62 TPC (2%): 102 TPC (3%): 124 TPC (4%): 158 TPC (5%): 164 TFC (control): nd TFC (1%): 26 TFC (2%): 57 TFC (3%): 76 TFC (4%): 138 TFC (5%): 168 | DPPH (control): 0.16 8 DPPH (1%): 1.00 8 DPPH (2%): 1.49 8 DPPH (3%): 2.08 8 DPPH (4%): 2.81 8 DPPH (5%): 2.66 8 FRAP (control): 0.70 8 FRAP (1%): 2.12 8 FRAP (2%): 3.40 8 FRAP (3%): 4.33 8 FRAP (4%): 5.27 8 FRAP (5%): 5.41 8 | Prokopov et al. [96] |

| Onion skin | Extract | Bread added with dried onion skin extract at a substitution level of 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5% (w/w) | TPC (control): ≈ 12 TPC (0.1%): ≈ 30 TPC (0.25%): ≈ 55 TPC (0.5%): ≈ 75 | DPPH (control): ≈ 23 9 DPPH (0.1%): ≈ 30 9 DPPH (0.25%): ≈ 100 9 DPPH (0.5%): ≈ 325 9 CUPRAC (control): ≈ 24 9 CUPRAC (0.1%): ≈ 30 9 CUPRAC (0.25%): ≈ 110 9 CUPRAC (0.5%): ≈ 185 9 | Piechowiak et al. [97] |

| Agri-Food Waste (AFW) | Functional Ingredient from AFW | AFW-Enriched Product | TPC and TFC | Antioxidant Capacity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carob germ | Powder/Flour | Bread added with carob germ flour (8% w/w) | TPC (control): 1.73 1 TPC (enriched): 5.53 1 | DPPH (control): 3.77 5 DPPH (enriched): 26.45 5 TEAC (control): 11.45 6 TEAC (enriched): 25.84 6 FRAP (control): 0.06 7 FRAP (enriched): 0.24 7 ORAC (control): 4.59 6 ORAC (enriched): 26.41 6 | Rico et al. [103] |

| Carob pod | Powder/Flour | Bread added with carob pod flour (8% w/w) | TPC (control): 1.73 1 TPC (enriched): 5.95 1 | DPPH (control): 3.77 5 DPPH (enriched): 22.16 5 TEAC (control): 11.45 6 TEAC (enriched): 26.05 6 FRAP (control): 0.06 7 FRAP (enriched): 0.27 7 ORAC (control): 4.59 6 ORAC (enriched): 29.56 6 | Rico et al. [103] |

| Carob seed peel | Powder/Flour | Bread added with carob seed peel flour (8% w/w) | TPC (control): 1.73 1 TPC (enriched): 2.32 1 | DPPH (control): 3.77 5 DPPH (enriched): 18.19 5 TEAC (control): 11.45 6 TEAC (enriched): 12.04 6,* FRAP (control): 0.06 7 FRAP (enriched): 0.09 7,* ORAC (control): 4.59 6 ORAC (enriched): 21.40 61 | Rico et al. [103] |

| Soybean and chickpea husk | Extract | White bread added with soybean or chickpea husk extract (2% w/w) | TPC (control): 23.2 2 TPC (enriched, soybean): 103.6 2 TPC (enriched, chickpea): 110.1 2 | DPPH (control): 0.354 6 DPPH (enriched, soybean): 1.096 6 DPPH (enriched, chickpea): 1.167 6 ABTS (enriched, control): 1.145 6 ABTS (enriched, soybean): 2.567 6 ABTS (enriched, chickpea): 3.035 6 FRAP (enriched, control): 0.819 6 FRAP (enriched, soybean): 1.800 6 FRAP (enriched, chickpea): 1.247 6 | Niño-Medina et al. [104] |

| Hazelnut testa | Powder/Flour | Bread added with hazelnut testa at a substitution level of 4, 6, 8, and 10% w/w | TPC (control bread): 205.7 2 TPC (4%):669.0 2 TPC (6%): 1058.1 2 TPC (8%): 1499.1 2 TPC (10%): 1942.7 2 | - | Velioǧlu et al. [105] |

| Hazelnut testa | Powder/Flour | Cookies added with hazelnut testa at a substitution level of 4, 6, 8, and 10% w/w | TPC (control): 156.8 2 TPC (4%): 497.7 2 TPC (6%): 654.5 2 TPC (8%): 808.0 2 TPC (10%): 977.7 2 | - | Velioǧlu et al. [105] |

| Hazelnut testa | Powder/Flour | Cake added with hazelnut testa at a substitution level of 4, 6, 8, and 10% w/w | TPC (control): 167.8 2 TPC (4%): 645.7 2 TPC (6%): 805.0 2 TPC (8%): 1134.2 2 TPC (10%): 1312.6 2 | - | Velioǧlu et al. [105] |

| Chia seed pomace | Powder/Flour | Wheat bread added with chia seed pomace (5% w/w) at 6 and 15% of fat content | TPC (control):≈ 23 2 TPC (enriched, pomace 6% fat): ≈ 29 2 TPC (enriched, pomace 15% fat): ≈ 28 2 | DPPH (control): 28 5 DPPH (enriched, pomace 6% fat): 35 5 DPPH (enriched, pomace 15% fat): 35 5 | Zdybel et al. [110] |

| Chia seed pomace | Powder/Flour | GF bread (maize and rice flour 1:1) with chia seed pomace (5% w/w substitution) at 6 and 15% of fat content | TPC (control):≈ 30 2 TPC (enriched, pomace 6% fat): ≈ 36 2 TPC (enriched, pomace 15% fat): ≈ 35 2 | DPPH (control): 33 5 DPPH (enriched, pomace 6% fat): 40 5 DPPH (enriched, pomace 15% fat): 40 5 | Zdybel et al. [110] |

| Coffee husk | Extract | GF bread added with coffee husk extract (2.5%) | TPC (control): 54.69 10 TPC (enriched): 121.12 10 Chlorogenic acid (control): nd Chlorogenic acid (enriched): 2 11 | TAC (control): 76.10 10 TAC (enriched): 129.39 10 | Guglielmetti et al. [107] |

| Coffee silver skin | Extract | GF bread added with coffee silver skin extract (2.5%) | TPC (control): 54.69 10 TPC (enriched): 254.92 10 Chlorogenic acid (control): nd Chlorogenic acid (enriched): 2511 | TAC (control): 76.10 10 TAC (enriched): 288.27 10 | Guglielmetti et al. [107] |

| Cocoa husk | Powder/Flour | Corn snack enriched with cocoa husk (5%, 10% and 15%) | TPC (non-extruded, control): 55.17 2 TPC (non-extruded, enriched 5%): 84.37 2 TPC (non-extruded, enriched 10%): 105.14 2 TPC (non-extruded, enriched 15%): 109.91 2 TPC (extruded, control): 48.63 2 TPC (extruded, enriched 5%): 72.25 2 TPC (extruded, enriched 10%): 83.99 2 TPC (extruded, enriched 15%): 105.68 2 | TAC (non-extruded, control): 11.03 5 TAC (non-extruded, enriched 5%): 11.24 5 TAC (non-extruded, enriched 10%): 19.60 5 TAC (non-extruded, enriched 15%): 23.47 5 TAC (extruded, control): 11.25 5 TAC (extruded, enriched 5%): 20.55 5 TAC (extruded, enriched 10%): 25.76 5 TAC (extruded, enriched 15%): 33.08 5 | Jozinović et al. [109] |

| Dry olive paste | Powder/Flour | Bread enriched by dry olive paste flour (10% w/w) | TPC (control): 28 2 TPC (enriched): 196 2 TFC (control): 6 3 TFC (enriched): 85 3 | ABTS (control): 0.24 8 ABTS (enriched): 21.64 8 | Cedola et al. 2019 [111] |

| Olive mill waste water (OMWW) and olive paste (OP) | Water and Powder/Flour | Bread added with i) olive mill wastewater (OMWW) (3:5 water:flour w/w), ii) olive paste (OP) (10% w/w), and iii) OMWW+OP | TPC (control): 14 2 TPC (OMWW): 49 2 TPC (OP): 133 2 TPC (OMWW +OP): 180 2 | ABTS (control): 0.046 8 ABTS (OMWW): 0.08 8 ABTS (OP): 0.42 8 ABTS (OMWW +OP): 0.67 8 FRAP (control): 1.8 7 FRAP (OMWW): 5.6 7 FRAP (OP): 17 9 FRAP (OMWW +OP): 25.3 7 | Cedola et al. 2020 [112] |

| Olive paste | Powder/Flour | “Taralli” added with fermented olive paste (20% w/w) from black olives of cultivar Cellina di Nardò (CdN) or Leccino (LEC) | TPC (control): nd TPC (enriched, CdN): 1377 4 TPC (enriched, LEC): 1016 4 | - | Durante et al. [113] |

| Olive-leaf extract | Extract | “Taralli” added with olive-leaf extract | TPC (control): 43 2 TPC (enriched): 61 2 TFC (control): 9 3 TFC (enriched): 36 3 | FRAP (control): 3.48 9 FRAP (enriched): 4.86 9 | Cedola et al. [114] |

| Olive pomace | Powder/Flour | Bread added with olive pomace (freeze-dried, 5% w/w) | Hydroxytyrosol (control): nd Hydroxytyrosol (enriched): 235 4 Tyrosol (control): nd Tyrosol (enriched): 43 4 | - | Cecchi et al. [115] |

| Olive pomace | Powder/Flour | Whole wheat bread (baker’s yeast fermented or sourdough) added with defatted olive pomace (4% w/w) | Baker’s yeast fermented: TPC (control): 756.1 4 TPC (enriched): 876.7 4 Sourdough fermented: TPC (control): 299.6 4 TPC (enriched): 617.2 4 | - | Di Nunzio et al. [116] |

| Olive pomace | Powder/Flour | Whole einkorn biscuits added with defatted olive pomace (2.5% w/w) | TPC (control): 226 4 TPC (enriched): 316 4 | - | Di Nunzio et al. [116] |

| Agri-Food Waste (AFW) | AFW-Enriched Product | In Vitro Method | Phenolic Compound Bioaccessibility/Bioavailability | Effect of Digestion on Antioxidant Capacity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broccoli stems | Bread enriched with broccoli by-product flour | Three sequential stages including a simulated salivary fluid (α—amylase, pH 7.0), gastric (pepsin, pH 3.0), and intestinal (pancreatin and fresh bile, pH 7.0) phase | TPC: ↑ after gastric stage (66%) ↑ after intestinal stage (164%) compared to the pre-digestion stage. | TAC: ↑ after gastric stage (419%, FRAP and 96% DPPH) and intestinal stage (429% FRAP and 104% DPPH) compared to the pre-digestion stage | Lafarga et al. [91] |

| Broccoli leaves | Bread enriched with broccoli by-product flour | Three sequential stages including a simulated salivary fluid (α—amylase, pH 7.0), gastric (pepsin, pH 3.0), and intestinal (pancreatin and fresh bile, pH 7.0) phase | TPC: ↑ after gastric stage (106%) and intestinal stage (170%) compared to the pre-digestion stage | TAC: ↑ after gastric stage (540%, FRAP and 112% DPPH) and intestinal stage (655% FRAP and 227% DPPH) compared to the pre-digestion stage. | Lafarga et al. [91] |

| Coffee husk | GF bread added with coffee husk extract (2.5%) | Three sequential stages including a salivary step (pH 6.9, 5 min, 3.9 U/mL amylase, aerobic), a gastric step (pH 2, 90 min, 71.2 U/mL pepsin, aerobic), and duodenal step (pH 7, 150 min, 9.2 mg/mL pancreatin and 55.2 mg/mL bile extract, aerobic) | TPC (control, digested): 227.92 mg CGA g−1 TPC (enriched, digested): 222.18 mg CGA g−1 * | TAC (insoluble fractions): ↑ by 34% compared to the digested control | Guglielmetti et al. [107] |

| Coffee silver skin | GF bread added with coffee silver skin extract (2.5%) | Three sequential stages including a salivary step (pH 6.9, 5 min, 3.9 U/mL amylase , aerobic), a gastric step (pH 2, 90 min, 71.2 U/mL pepsin, aerobic), and duodenal step (pH 7, 150 min, 9.2 mg/mL pancreatin and 55.2 mg/mL bile extract, aerobic) | TPC (control, digested): 227.92 mg CGA g−1 TPC (enriched, digested): 265.70 mg CGA g−1 | TAC (insoluble fractions): ↑ by 53% compared to the digested control | Guglielmetti et al. [107] |

| Olive oil paste | Bread enriched by dry olive paste flour (10% w/w) | Three-stage simulated digestion including oral, gastric and small intestinal phase | Bioaccessibility of polyphenols of digested bread with dry olive paste addition was ≈ 70% In digested control bread, bioaccessibility of polyphenols was 60% | - | Cedola et al. [111] |

| Olive-leaf extract | “Taralli” added with olive-leaf extract | Three-stage simulated digestion including oral, gastric and small intestinal phase | TPC (before digestion): 54 mg GAE/100 g TPC (after digestion): 323 mg GAE/100 g TFC (before digestion): 36 mg QE/100 g TFC (after digestion): 88 mg QE/100 g | TAC (before digestion): 4.86 µmol FeSO4 7H2O/g TAC (after digestion): 20.98 µmol FeSO4 7H2O/g | Cedola et al. [114] |

| Artichoke stem powder (ASP) at 3, 6 and 9% (w/w) substitution | Bread enriched with artichoke stem powder | Three sequential stages including a simulated salivary fluid (α--amylase), gastric phase (porcine pepsin, pH 3.0), and intestinal fluid (pancreatin and fresh bile) | TPs (3% ASP bread): 649.3 µg g−1 DM (after duodenal phase) 121.3 µg g−1 DM (after colon phase) TPs (6% ASP bread): 1423.0 µg g−1 DM (after duodenal phase) 321.8 µg g−1 DM (after colon phase) TPs (9% ASP bread): 1958.6 µg g−1 DM (after duodenal phase) 520.5 µg g−1 DM (after colon phase) | - | Colantuono et al. [117] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melini, V.; Melini, F.; Luziatelli, F.; Ruzzi, M. Functional Ingredients from Agri-Food Waste: Effect of Inclusion Thereof on Phenolic Compound Content and Bioaccessibility in Bakery Products. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121216

Melini V, Melini F, Luziatelli F, Ruzzi M. Functional Ingredients from Agri-Food Waste: Effect of Inclusion Thereof on Phenolic Compound Content and Bioaccessibility in Bakery Products. Antioxidants. 2020; 9(12):1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121216

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelini, Valentina, Francesca Melini, Francesca Luziatelli, and Maurizio Ruzzi. 2020. "Functional Ingredients from Agri-Food Waste: Effect of Inclusion Thereof on Phenolic Compound Content and Bioaccessibility in Bakery Products" Antioxidants 9, no. 12: 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121216

APA StyleMelini, V., Melini, F., Luziatelli, F., & Ruzzi, M. (2020). Functional Ingredients from Agri-Food Waste: Effect of Inclusion Thereof on Phenolic Compound Content and Bioaccessibility in Bakery Products. Antioxidants, 9(12), 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121216