Abstract

Mitochondria produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) while also generating high amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) derived from oxygen metabolism. ROS are small but highly reactive molecules that can be detrimental if unregulated. While normally functioning mitochondria produce molecules that counteract ROS production, an imbalance between the amount of ROS produced in the mitochondria and the capacity of the cell to counteract them leads to oxidative stress and ultimately to mitochondrial dysfunction. This dysfunction impairs cellular functions through reduced ATP output and/or increased oxidative stress. Mitochondrial dysfunction may also lead to poor oocyte quality and embryo development, ultimately affecting pregnancy outcomes. Improving mitochondrial function through antioxidant supplementation may enhance reproductive performance. Recent studies suggest that antioxidants may treat infertility by restoring mitochondrial function and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis. However, further randomized, controlled trials are needed to determine their clinical efficacy. In this review, we discuss the use of resveratrol, coenzyme-Q10, melatonin, folic acid, and several vitamins as antioxidant treatments to improve human oocyte and embryo quality, focusing on the mitochondria as their main hypothetical target. However, this mechanism of action has not yet been demonstrated in the human oocyte, which highlights the need for further studies in this field.

1. Introduction

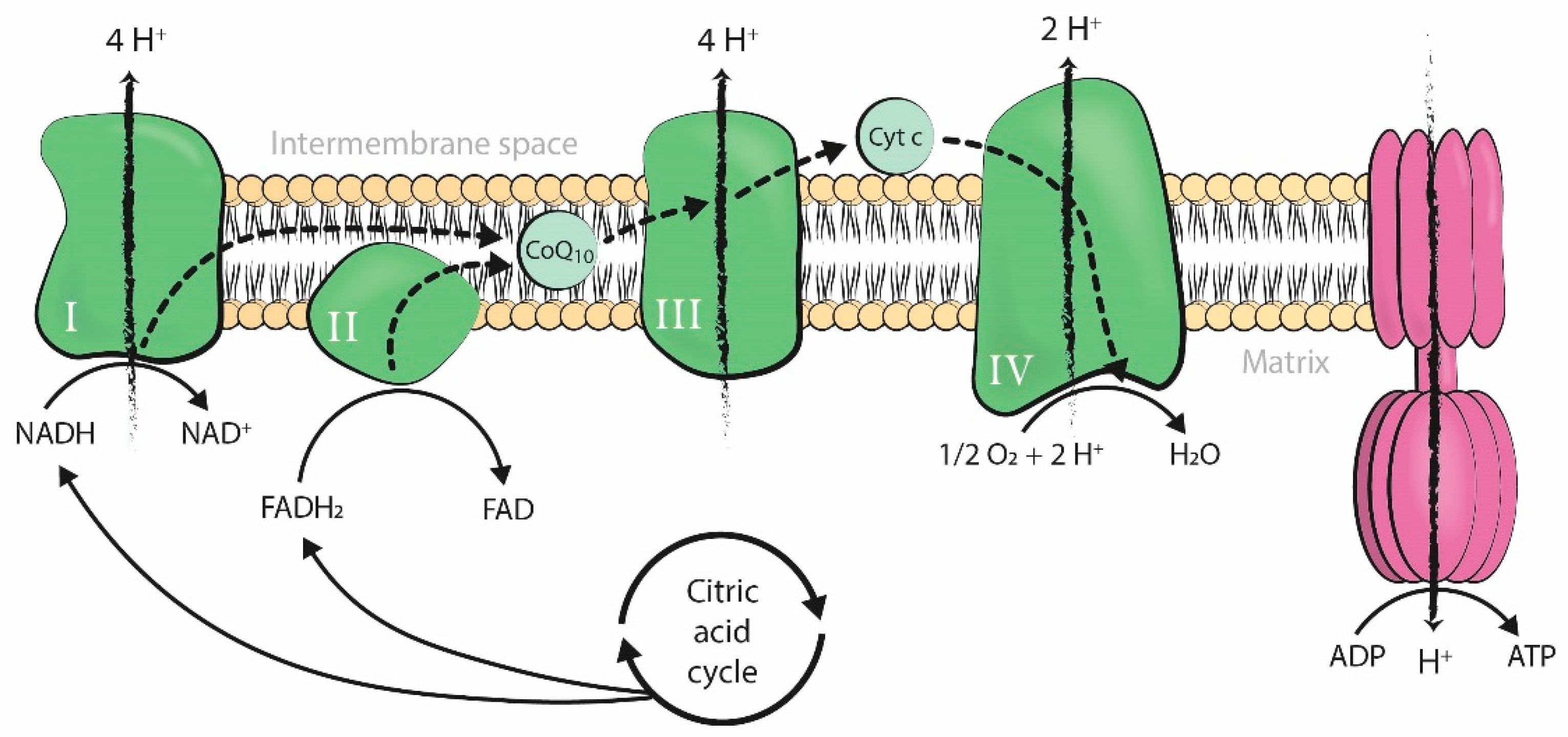

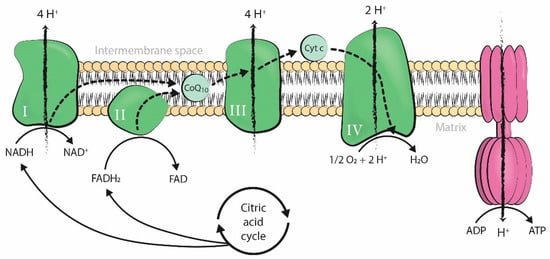

Mitochondria produce the energy required by cells to carry out all cellular processes. Energy is generated in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through oxidative phosphorylation, a process that takes place in the inner mitochondrial membrane under aerobic conditions. Along this membrane, electrons from the controlled oxidation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) or flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2), both products of the citric acid cycle, travel through several enzymatic complexes forming the electron transport chain (ETC). The movement of electrons throughout the ETC is coupled with the transfer of protons across the membrane into the intermembrane space, generating an electrochemical proton gradient over the inner mitochondrial membrane that is harnessed by F1-F0 ATPase to phosphorylate adenosine diphosphate (ADP) into ATP [1] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by oxidative phosphorylation coupled to the mitochondrial electron transport chain. The four enzymatic complexes (I, II, III, and IV) and ATP synthase are represented in the inner mitochondrial membrane. ADP: adenosine diphosphate; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; Pi: inorganic phosphate; H+: hydrogen ion (proton); NADH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form; FADH2: flavin adenine dinucleotide, reduced form; NAD+: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, oxidized form; FAD: flavin adenine dinucleotide, oxidized form; O2: oxygen; H2O: water; Cyt c: cytochrome c; CoQ10: coenzyme-Q10.

Mitochondrial respiration is a form of aerobic metabolism and uses oxygen to produce energy, with oxygen as the ultimate electron acceptor of the electron flow system of the mitochondrial ETC. However, mitochondrial electron flow may become uncoupled at several sites along the chain, resulting in unpaired single electrons that react with oxygen or other electron acceptors and generate free radicals. When these electrons react with oxygen, the resulting free radicals are referred to as reactive oxygen species (ROS). These include the superoxide anion (O2•−), which forms hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and can further react to form the hydroxyl radical (HO•). Unrelated to respiration, there is also a large source of H2O2 in the outer mitochondrial membrane due to monoamine oxidase catalytic activity [1,2].

Physiological levels of ROS are required for normal cellular function [3]. However, ROS are also highly reactive molecules that can damage mitochondrial components, initiate degradative processes, deregulate essential cellular functions, and initiate many pathological conditions if generated uncontrollably [1]. Therefore, many organisms have developed a system of antioxidant defense, in which mitochondria play a major role as antioxidant producers, allowing them to maintain balanced levels of oxidants and antioxidants [3]. An antioxidant is any substance that delays the oxidation of lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, or DNA by directly scavenging ROS or by indirectly up-regulating antioxidant defenses or inhibiting ROS production. There are many different endogenous and exogenous sources of antioxidants [3,4], but the first line of defense is also the main ROS producer in the cell: the mitochondria.

Antioxidants counteract the high levels of ROS derived from mitochondrial metabolism, reducing damage to the cell. However, an imbalance between the amount of antioxidants and ROS produced, in favor of the latter, leads to oxidative stress [3]. Oxidative stress generates lipid peroxidation [5], as well as RNA, DNA, and protein oxidation, which in turn leads to their selective enzymatic degradation by nucleases and proteases [2]. On the one hand, lipid peroxidation affects the integrity of cell membranes [5]. On the other hand, nuclear DNA degradation induces the onset of apoptosis [6] and occurs at the same time as the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c (Cyt c) [2], which is also responsible for the initiation of programmed cell death [7]. Oxidative stress may also interfere with essential mitochondrial functions within the cell by promoting the inactivation of enzymes from the mitochondrial ETC [8] and by increasing mtDNA mutations. In fact, mitochondrial DNA is prone to mutations because it lacks protective histones and is in close proximity to the inner mitochondrial membrane [9]. Finally, oxidative stress has also been related to telomere shortening and senescence [10].

Oxidative stress can be caused by, or be the cause of, mitochondrial dysfunction (MD). MD reduces the production of ATP and synthesis of antioxidant molecules, creating a cycle in which ROS-induced mitochondrial damage results in higher oxidant production and further mitochondrial impairment [11]. MD is involved in the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and atherosclerosis [12,13]. In the reproductive field, MD is related to a decline in oocyte quality [14]. Mitochondria are essential organelles involved in meiotic spindle assembly, proper segregation of chromosomes, maturation, fertilization, and embryo development [15]. Therefore, MD may affect the quality and DNA content of oocytes, embryo development, and pregnancy outcome. The consequences of MD are not limited to the short-term, as oxidative stress exposure during the gestational period is related to long-lasting cardiovascular effects [16].

Regardless of origin, oxidative stress and MD are triggered by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include biological age [11,17], endometriosis [18], polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) [19], and premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) [20]. Extrinsic factors include environmental exposure to ROS inducers or producers, such as diet, professional exposure, and assisted reproduction treatment (ART) techniques [21]. Some of these factors are modifiable and, therefore, offer opportunities for intervention.

ROS are natural products of sperm, oocyte, and embryo metabolism. However, gamete manipulation during ART procedures increases ROS either through indirect intracellular ROS production in response to external stressors or through direct exogenous ROS production by environmental factors. The risk of oxidative stress development is higher in vitro than in vivo, although it remains unclear to what extent ART is responsible for higher levels of oxidative stress [21]. Despite recent advancements in ART techniques [22,23,24,25], the in vitro fertilization (IVF) setting does not recreate the conditions of natural fertilization, which includes tight physiological regulation of oxidative stress by antioxidants. Oxygen concentration, temperature variation, high light exposure, culture media composition, and cryopreservation methods are environmental sources of oxidative stress in the IVF laboratory [21], implicating the need for antioxidant supplementation in the IVF setting. Indeed, human IVF culture media are supplemented with combinations of molecules with antioxidant properties, including human serum albumin, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, folic acid, ascorbic acid, and pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), among others [25] (see Supplemental Data).

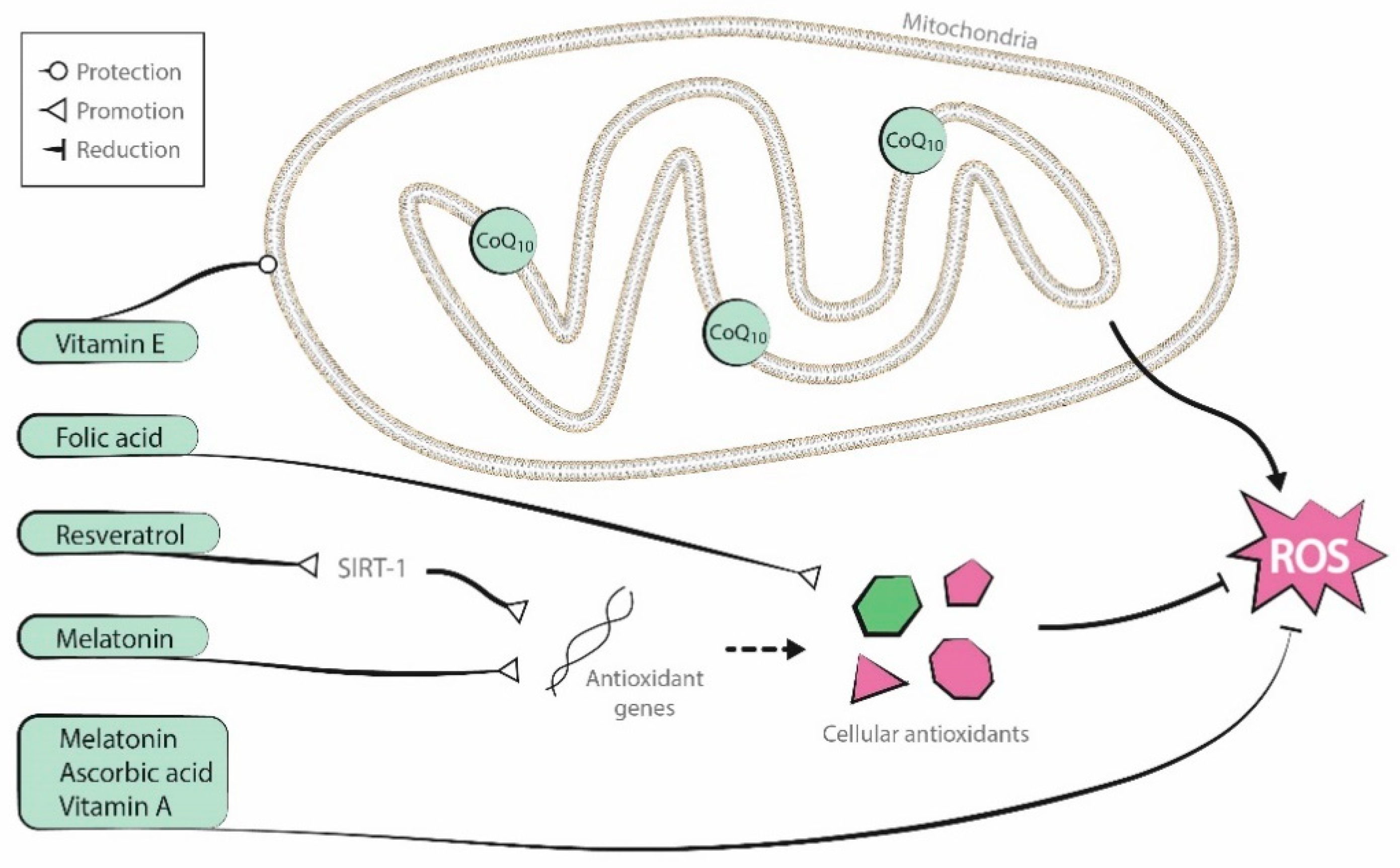

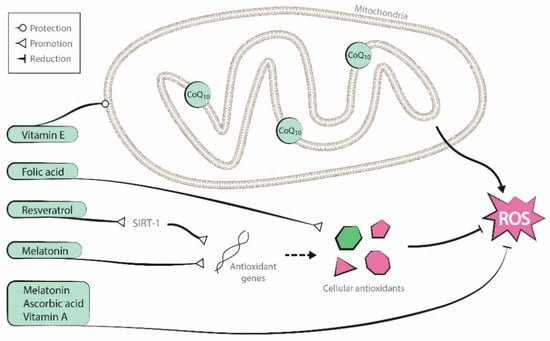

Antioxidants are endogenous to organisms, but it is uncertain if supplementation of these substances can improve oocyte mitochondrial function. Although several supplementary antioxidant molecules have shown promising results [26,27,28], two recent Cochrane reviews described low-quality evidence about the positive effects of oral antioxidant treatment in live birth and clinical pregnancy rates in women attending an infertility clinic [29,30]. In this review, we describe the effects of several antioxidant supplementation treatments in human oocytes and embryos. The antioxidants discussed include coenzyme-Q10, resveratrol, melatonin, and vitamins A, B (folic acid), C (ascorbic acid), D, and E. Figure 2 presents a graphic representation of their antioxidant properties.

Figure 2.

Antioxidant properties of the molecules reviewed (coenzyme-Q10, resveratrol, melatonin, and vitamins A, B, C, and E).

2. Antioxidant Supplementation in Reproduction

Antioxidant treatment in the reproductive field can be carried out either by oral supplementation before infertility treatment or by culture media supplementation during ART. Oral supplementation attempts to improve gamete quality in vivo, while culture media supplementation attempts to do so in vitro. The latter approach can also be used to improve the in vitro maturation (IVM) process and to counteract high ROS production within the IVF setting.

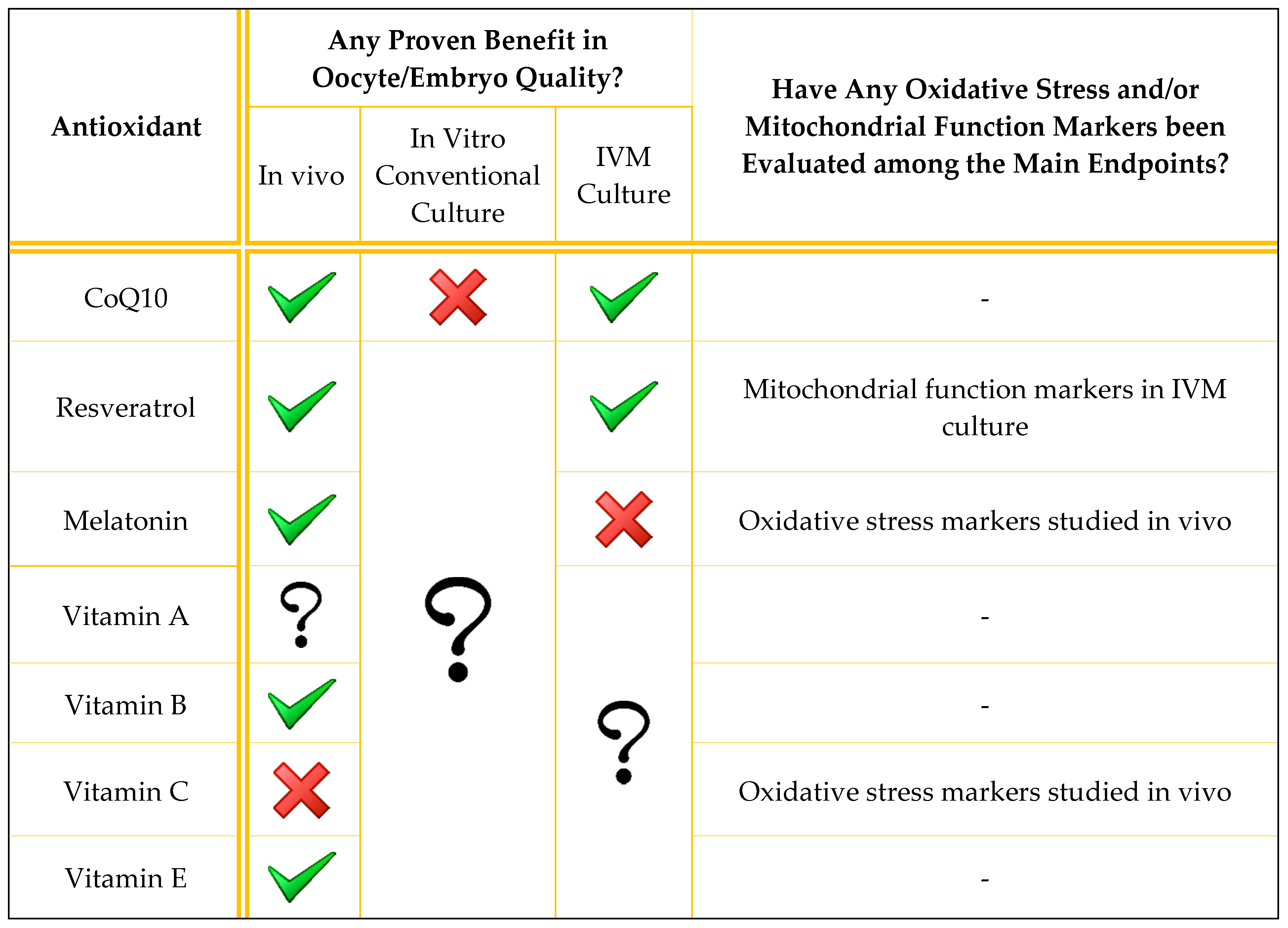

Antioxidant supplementation is generally described in the literature as being applied to the male [31]. In this review, we discuss the use of antioxidants to improve oocyte and embryo quality, both in vivo and in vitro. We focus on mitochondrial function because its enhancement may be the main mechanism by which antioxidants manage to improve gamete quality. However, although mitochondrial function has been restored by different antioxidant molecules in many other tissues [32,33,34,35], this direct association has not yet been demonstrated in the human oocyte. A summary of the main evidence regarding the current utility of each of the antioxidants described is presented in Table 1, while a more extensive summary of the results of the discussed human studies is presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Brief summary of evidence from published studies on the utility of the antioxidants reviewed. Only human studies are summarized. A green tick means that at least one study found beneficial effects on oocyte/embryo quality; a red cross means that the studies reviewed did not find any beneficial effects; a question mark means that the antioxidant effect has not been studied in that scenario.

Table 2.

Summary of clinical trials conducted to evaluate antioxidant supplementation protocols in vitro and in vivo to improve oocyte quality. p-values > 0.05 are presented as p = NS (non-significant). Gr.: group. RCT: randomized controlled trial. y.o.: years old. CPR: clinical pregnancy rate. MR: miscarriage rate. LBR: live birth rate. GV: germinal vesicle. OR: odds ratio. CI: confidence interval. IVM: in vitro maturation. hCG: human chorionic gonadotropin. MII: metaphase II. IVF: in vitro fertilization.

2.1. Coenzyme-Q10

Coenzyme-Q10 (CoQ10) carries electrons from complexes I and II to complex III in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and participates in the synthesis of ATP [36] (Figure 1). CoQ10 is a source of superoxide anion radical, though it also acts as an antioxidant, making it both a prooxidant and an antioxidant. The reduced form of CoQ10, ubiquinol, protects biological membranes from lipid peroxidation by recycling vitamin E and is also an antioxidant [37].

The dual role of CoQ10 in controlling mitochondrial function makes it an essential molecule for cellular performance. CoQ10 plasma levels decrease with advancing age, and this decline coincides with a decline in fertility and an increase in embryo aneuploidies [38]. Supplementation with CoQ10 may improve the reproductive outcome in infertile patients by improving mitochondrial function. Indeed, preovulatory CoQ10 supplementation improves mitochondrial function in aged mice [39] and improves non-aging related MD in mice [40] and other species [41]. In addition, CoQ10 treatment prevented mitochondrial ovarian aging in a rat model [42]. CoQ10 supplementation in culture media also restored the age-induced deterioration of oocyte quality in mice [43] and porcine models [44]. Finally, CoQ10 injected into aged mice increased mitochondrial respiratory activity and glucose uptake in cumulus cells, as well as the number of cumulus cells per oocyte, leading to improved reproductive capacity. These findings suggest that CoQ10 supplementation can benefit not only oocytes but also cumulus cells; this can be translated to humans because the human aging process also leads to reduced CoQ10-synthesis gene expression in cumulus cells [45].

Use of Coenzyme-Q10 in Infertility

In humans, higher CoQ10 levels in follicular fluid are related to improved embryo quality and higher pregnancy rates [46]. However, although CoQ10 supplementation increases CoQ10 levels in follicular fluid in infertile patients [47], clinical outcome results are inconclusive. CoQ10 supplementation (600 mg/day for 2 months and up to the day of oocyte retrieval) in women with infertility of advanced age (between 35 and 43 years old) was insufficient to prevent ROS prolonged exposure effects on the meiotic apparatus because there was no significant difference in aneuploidy rates between the treated and the control groups. However, the study ended prematurely due to concerns related to the possible deleterious effects of polar body biopsy on embryo quality and implantation. The study did not recruit the number of participants initially proposed, which could underlie the non-significant difference in aneuploidy rate (46.5% CoQ10 group vs. 62.8% control group) [26]. Moreover, the dose and duration of CoQ10 treatment were based on mice studies, so humans may require longer exposure or higher doses to achieve remarkable benefits [26].

Similarly, CoQ10 supplementation (600 mg/day for 2 months before ovarian stimulation) increased ovarian response [mean (interquartile range, IQR); 4 (2,5) vs. 2 (1,4) oocytes; p = 0.002], fertilization rates (67.5% vs. 45.1%; p = 0.001), and the number of high-quality embryos [1 (0,2) vs. 0 (0,1.75); p = 0.03] in young women with poor ovarian reserve. However, no differences in clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, or live birth rates were observed [48]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) indicated that CoQ10 oral supplementation, as an IVF pre-treatment, increased clinical pregnancy rates (CPR) in comparison with a placebo or no treatment [28.8% vs. 14.1%; odds ratio (OR) 2.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.30–4.59, p = 0.006]. However, characteristics of the study population, as well as the dose and duration of CoQ10 treatment, were highly heterogeneous between the studies analyzed. No differences were observed in live birth rates (LBRs) (28% vs. 17.4%; OR 1.67, 95% CI 0.66—4.25, p = 0.28), or miscarriage rates (MR) (10% vs. 13.6%; OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.14–2.76, p = 0.52, in treated and untreated women, respectively). The lack of statistical power may be explained by insufficient data regarding these two variables [49].

Additionally, CoQ10 supplementation benefited PCOS patients who exhibited ovulatory disorders and a higher proportion of immature follicles within the ovary [19]. Indeed, an RCT showed a significant increase in the number of follicles ≥14 and 18 mm of clomiphene citrate (CC)-resistant PCOS patients after the addition of CoQ10 as an adjuvant to CC treatment [50].

CoQ10 supplementation is proposed as an adjuvant during IVM, which may promote this technique by improving mitochondrial function in immature oocytes. Despite the initial discrepancies between animal studies [51,52], a 2020 report by Ma et al. described increased maturation rates (82.6% vs. 63.0%; p = 0.035) and reduced post-meiotic aneuploidies (36.8% vs. 65.5%; p = 0.02) after IVM in oocytes from women of advanced age supplemented with CoQ10. They did not find significant differences in young women [53]. However, mitoquinol (a CoQ10 analog) addition to the culture media from fertilization until the blastocyst stage did not improve embryo quality in women of advanced age. There were no significant differences in day 5 (18% vs. 20%) or total (48% vs. 45%) good quality blastocyst development per zygote, total blastocyst development (63% vs. 62%), and euploidy rates (33% vs. 30%) between the control and the treatment groups, respectively [54].

In sum, although CoQ10 is a promising therapy and is non-pharmaceutical, inexpensive, and safe, there is a need for well-designed clinical trials involving a greater number of patients to fully assess the effects of CoQ10 treatment on human fertility.

2.2. Resveratrol

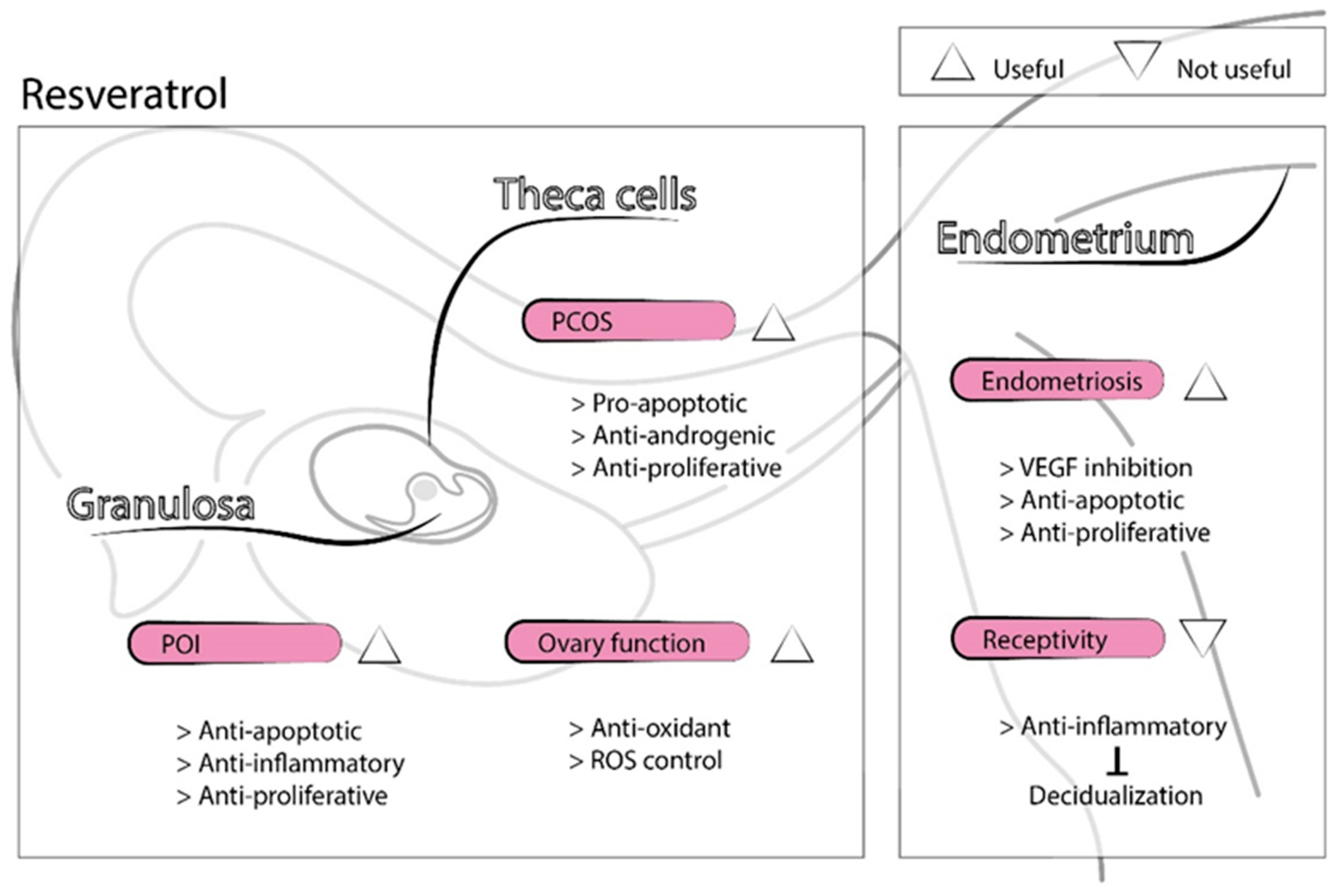

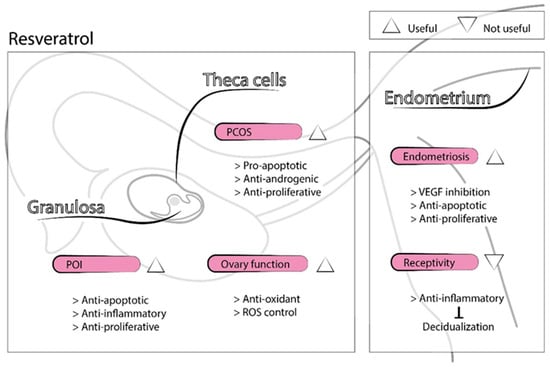

Resveratrol is a natural polyphenol synthetized by several plants in response to pathogens. It is found in grapes, red wine, peanuts, and several medicinal plants [55]. Over the past decade, resveratrol has emerged as a therapeutic treatment for many diseases due to its anti-aging, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, insulin-sensitizing, cardioprotective, vasodilating, and anti-neoplastic properties [56]. In the reproductive field, resveratrol may benefit women with diminished ovarian function, PCOS, endometriosis, and uterine fibroids [55,57,58,59]. Resveratrol may improve age-related decline in ovarian function through the activation of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) [60], a molecule that protects mitochondrial function from oxidative stress and whose levels are undetectable in aged oocytes [61]. In rats, resveratrol supplementation inhibited the process of follicular atresia, increased ovarian follicular reserve, and prolonged ovarian lifespan [62]. Moreover, mice treated with resveratrol for 12 months exhibited a higher number of follicles than controls and improved the number and quality of oocytes, evidenced by proper spindle morphology and chromosome alignment. In addition, telomerase activity, telomerase length, and age-related gene expression in the ovaries of mice supplemented with resveratrol resembled those of younger mice [63]. Resveratrol may also improve ovarian dysfunction caused by POI through the inhibition of the PI3K/AKT [64] and the NF-kB signaling pathways [65]. Resveratrol inhibited oxidative stress and inflammatory events in a rat POI model [66], and its antiapoptotic effect prevented oogonial stem cell loss in a mouse model of POI [67]. Furthermore, the addition of resveratrol to culture media improved oocyte maturation and embryo developmental potential in different animal studies, both in IVM [68,69] and conventional in vitro culture [70], by decreasing ROS production and increasing ATP content. Resveratrol may enhance mitochondrial homeostasis in both oocytes and granulosa cells via SIRT1 activation and regulation of the balance between mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy [69]. Resveratrol may also have an antiapoptotic effect on granulosa cells through the inhibition of NF-kB signaling [65]. Nevertheless, the effects of resveratrol depend largely on cell type [55]. Contrary to granulosa cells, resveratrol exerts a proapoptotic effect on theca cells and counteracts insulin’s stimulatory effect on cell proliferation [71]. In addition, resveratrol inhibits theca-interstitial cell androgen production, primarily by inhibiting the rate-limiting enzyme in the androgen biosynthesis pathway [72]. Therefore, it is useful in PCOS treatment, a pathology related to insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia, theca-interstitial cell hyperplasia, and hyperandrogenism [55]. In vivo studies have demonstrated the antioxidant effect of resveratrol and its ability to return ovarian morphology to normal limits in a PCOS rat model [73].

In the endometrium, resveratrol’s antiapoptotic and anti-proliferative effects inhibited the progression of ectopic endometrium, countering endometriosis [58]. In addition, resveratrol reduced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression [74], improving the treatment of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and endometriosis, both gynecologic disorders associated with excessive VEGF activity [55]. However, its anti-inflammatory properties may inhibit the inflammatory-related process of decidualization [75], leading to decreased endometrial receptivity.

Therefore, resveratrol has the potential to benefit women with diminished ovarian reserve and function through its antioxidant effects and the stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis, though it also has adverse effects on implantation and endometrial decidualization [76] (Figure 3). Human studies involving resveratrol are needed to validate the success observed in animal models.

Figure 3.

Representation of resveratrol’s physiological functions in the reproductive field.

Use of Resveratrol in Infertility

In humans, resveratrol supplementation in the IVM medium of aged immature oocytes demonstrated improved oocyte maturation rates after 24 h (55.3% vs. 37.84%; p < 0.05) and 36 h of culture (71.1% vs. 51.35% in the study and control group, respectively; p < 0.05). Resveratrol also improved oocyte quality, as evidenced by improved mitochondrial immunofluorescence intensity (53.0% vs. 31.1%, p < 0.05) and a reduced proportion of oocytes with abnormal spindle morphology and irregular chromosomal disposition (p < 0.05) [68]. In a double-blind RCT, oral resveratrol (1500 mg/day) supplementation in women with PCOS showed reduced ovarian and adrenal androgen levels [77]. A triple-blinded RCT comparing 800 mg/day of resveratrol to a placebo in patients with PCOS found an increased high-quality oocyte rate (81.9% vs. 69.1%; p = 0.002), increased high-quality embryo rate (89.8% vs. 78.8%; p = 0.024), and reduced expression of the VEGF gene in granulosa cells (p = 0.0001) [78]. Finally, a retrospective study evaluated the impact of resveratrol (200 mg/day) on human pregnancy outcomes during fresh or frozen embryo transfer cycles compared to no treatment. The study group showed significantly lower clinical pregnancy rates (10.8% vs. 21.5%; p = 0.0005), as well as higher miscarriage rates (52.4% vs. 21.8%; p = 0.0022), even after a multivariate logistic regression analysis (CPR: OR 0.539, 95% CI 0.341–0.853; MR: OR 2.602, 95% CI 1.070–6.325). Patients with resveratrol treatment had poor pregnancy outcomes, even though good quality embryos had been transferred [27], which may be related to the suppressor effect of resveratrol on decidualization [75]. This study focused on pregnancy outcomes after embryo transfer and did not evaluate ovarian function before or after resveratrol treatment [76].

Following these results, an alternative resveratrol administration protocol was proposed to avoid negative effects on the endometrium. Because the half-life of resveratrol is between 3 and 9 h [79], it may not affect implantation or pregnancy if its endometrial tissue levels drop before decidualization. Thus, discontinuation of resveratrol intake on the day of ovulation, or the freeze-all policy with a deferred frozen embryo transfer without supplementation, may help overcome these adverse effects [76].

Resveratrol may have adverse effects depending on the dose administered. Some side effects were reported after its administration, including headaches, nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, and liver dysfunction [79]. High-dose resveratrol should not be administered, and its supplementation should be discontinued during pregnancy due to its negative effect on the endometrial decidualization process and scarce data about adverse effects and embryo-fetal toxicity. Randomized controlled trials are needed along with human studies to define a standard dose and duration of treatment since there is a high heterogeneity between all the studies described [55].

2.3. Melatonin

Melatonin is synthesized from the amino acid tryptophan, almost exclusively by the pineal gland. It is released into the blood in a circadian manner, and its production is restricted to nighttime [80]. Melatonin may be produced in high amounts in mitochondria [34], and it has an important role in reducing oxidative stress. Its antioxidant properties come from its excellent free radical scavenging, as well as its capacity to upregulate the expression of antioxidant enzymes and a spectrum of stress-responsive genes. In addition, melatonin indirectly accelerates electron transport through the ETC, decreasing electron leakage and reducing ROS formation, a process called radical avoidance [81]. Moreover, this molecule has antiapoptotic [82], anti-inflammatory [83], and antiandrogenic properties [84].

Melatonin modulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis at different levels, thus modulating reproductive system activity [85]. Melatonin may reduce intrafollicular oxidative stress, and melatonin levels in follicular fluid are suggested as a biomarker to predict IVF outcomes and ovarian reserve [86]. Melatonin production decreases with age [87], and in the ovary, this age-related decline is related to the increase in follicle-stimulating hormone levels associated with menopause [88]. Therefore, melatonin may delay ovarian aging. Interestingly, Song et al. found reduced aging ovary parameters, increased oocyte quality and quantity, and increased litter size in mice treated with melatonin for 12 months [89].

Use of Melatonin in Infertility

In humans, melatonin treatment improves fertility outcomes in infertile women [28,90,91,92], patients with PCOS [84], patients with endometriosis, and many other gynecologic pathologies. In addition, melatonin may help normalize menstrual disorders, such as dysmenorrhea [93]. Further, melatonin supplementation during pregnancy may protect the embryo from oxidative stress since this hormone crosses the placental barrier during pregnancy [94].

Melatonin supplementation is proposed as a treatment for poor oocyte quality due to its antioxidant effect in oocytes and granulosa cells. In 2003, Takasaki et al. found that melatonin treatment (3 mg/day from the previous cycle until the day of triggering) improved oocyte quality in women with a previous IVF failure due to poor oocyte quality. However, this improvement was evidenced only in the number of degenerated oocytes retrieved and not in the number of oocytes or mature oocytes obtained. In the treatment group, melatonin levels were significantly higher in the follicular fluid, while levels of lipid peroxide were reduced [90]. Lipid peroxide is implicated in free radical reactions [5]. Furthermore, melatonin accelerates the action of the maturation-inducing hormone, a molecule important to final oocyte maturation [95]. Thus, melatonin may improve oocyte quality by protecting oocytes from oxidative stress and enhancing the oocyte maturation processes.

Clinical trials found that melatonin supplementation during an IVF cycle significantly increased the number of retrieved (11.5 vs. 6.9 in the control group; p = 0.0001) and mature oocytes (9.0 vs. 4.4 in the control group; p = 0.0001) [28], or at least the proportion of metaphase II (MII)/retrieved oocytes (81.9% vs. 75.8% in the control group; p = 0.034) [92]. In addition, the fertilization success of women with low fertilization rates (≤50%) in the previous IVF cycle was improved by melatonin treatment compared to the previous cycle (29.8% increment in the melatonin group vs. 1.9% increment in the non-melatonin group; p < 0.01) [91]. However, an RCT conducted in 2018 found no difference in the number of oocytes retrieved, number of MII, fertilization rate, embryo quality, clinical pregnancy rate, or live birth rate between the treatment and control groups [96].

In 2019, Espino et al. found reduced concentrations of melatonin at the systemic level and in the follicular fluid of women with unexplained infertility. Interestingly, melatonin levels were correlated with different parameters of oxidative balance in follicular fluid. In comparison with a control group of fertile women, patients with unexplained infertility who underwent melatonin supplementation during ovarian stimulation until the day of oocyte retrieval (one group 3 mg/day and the other group 6 mg/day) had better outcomes than patients with no melatonin treatment. This supplementation restored concentrations of diverse oxidative stress markers, improved oocyte quality, and, consequently, increased the number of transferable embryos and the success of ART [97]. Lastly, melatonin supplementation of culture media also improved outcomes in animal studies in IVM [98] and conventional in vitro culture [99]. IVM of immature oocytes from PCOS patients cultured with melatonin achieved elevated but not significantly higher maturation rates [100].

The main advantage of melatonin antioxidant therapy is its relatively well-documented safety due to its frequent use as a sleep aid [101]. However, studies conducted so far have evaluated melatonin only in the short-term, so long-term clinical trials are needed [102].

2.4. Vitamins

Despite their proven antioxidant properties, the use of vitamins as supplements to improve mitochondrial oocyte function has not been extensively addressed. No human clinical trials have assessed the role of vitamins as antioxidants in improving oocyte and embryo quality in IVF patients.

2.4.1. Vitamin A

Vitamin A is a lipid-soluble vitamin obtained from the diet in the form of vitamin A esters or provitamin A carotenoids. Dietary sources of vitamin A include green and yellow vegetables, dairy products, fish, eggs, and organ meats. There are at least a dozen forms of vitamin A esters and approximately 600 types of carotenoids, although only about 50 forms of the latter have provitamin A activity. Once within the body, physiologically active forms of vitamin A are retinol, retinal, and retinoic acid [103].

Antioxidant activity has been described for retinol, the main physiological form of vitamin A, as well as for α and β carotenes, two examples of provitamin A carotenoids. Vitamin A forms are potent antioxidants that act by scavenging peroxyl radicals, thus reducing ROS levels [103]. In the reproductive field, vitamin A and its metabolites have important roles in follicular growth [104], steroidogenesis [105], oocyte maturation [106,107], and embryo development [108]. Its supplementation has been tested in both in vivo [109,110] and in vitro studies. In vitro studies found that vitamin A addition to IVM medium increased maturation rates by enhancing mitochondrial membrane potential activity, lowering ROS levels, and decreasing apoptosis [111]. Indeed, retinoic acid supplementation to the IVM medium has obtained beneficial results in several species, including cows [112] and mice [113].

Use of Vitamin A in Infertility

In humans, high follicular fluid levels of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), the active metabolite of retinol, at the time of oocyte retrieval, were related to oocytes giving rise to embryos of the highest quality. In addition, follicular fluid ATRA concentrations were positively correlated with patient serum ATRA [114]. A later study from the same group confirmed that this higher oocyte competence was the result of higher ATRA synthesis of cumulus-oocyte complexes, which in turn was positively correlated with higher fertilization rates [115].

Therefore, minimum levels of vitamin A or its metabolites are essential for proper oocyte maturation and acquisition of competence. However, due to the essential role of vitamin A in the signaling pathways that control ovarian function, including oocyte maturation and development [116], it is unknown if its antioxidant properties also play a role in these processes. In any case, human clinical trials assessing the effect of vitamin A supplementation in oocyte quality have not been performed yet, neither in vitro nor in vivo.

2.4.2. Folic Acid

Folate, or vitamin B9, is a B vitamin found in green leafy vegetables, dark green vegetables, beans, and other legumes. The synthetic form of folate, folic acid, is common in dietary supplements in fortified foods due to its high stability and low cost [117]. At the cellular level, folate acts as a methyl donor to support the methylation of homocysteine to become methionine [118], which is a critical intermediary in the production of glutathione, the primary intracellular antioxidant. Therefore, folic acid may protect from oxidative stress by increasing intrinsic antioxidant levels within the cell. In addition, different molecules derived from folate metabolism are also essential to DNA, RNA, protein synthesis, proper epigenetic activity, and chromosome structure maintenance, making folate indispensable during periods of rapid cell growth and proliferation, such as germ cell maturation, pregnancy, and fertilization [119].

In Europe, the recommended folate intake in adult women ranges from 170 to 300 µg/day, and 400 µg/day of supplemental folic acid is recommended for pregnant women [120]. Folate deficiency can occur due to poor dietary intake, either of folate itself or of the micronutrients necessary for its synthesis, and/or malabsorption, mainly by defects in folate-metabolizing genes. Folate deficiency leads to homocysteine accumulation [121] or hyperhomocysteinemia, which is associated with several pathophysiological mechanisms during pregnancy, including oxidative stress [122] and decreased cellular antioxidant potential [123].

Preconception folate deficiency hampered female fertility, as well as embryo and fetal viability, in several animal models. This condition partially inhibits ovulation in rats [124] and increases the number of degenerated follicles in rhesus monkeys [125], suggesting the essential role of folate in folliculogenesis [119]. In humans, women with folate deficiency undergoing ovarian stimulation often have impaired ovarian function, lower oocyte quality, and lower pregnancy rates [126,127]. However, no human studies have hypothesized a relationship between folate deficiency-related mitochondrial impairment and reduced fertility.

Folic acid supplementation, therefore, may be useful in the reproductive field. Its use during pregnancy is widespread, as it seems to prevent fetal neural tube defects [128] as well as heart defects [129], Down syndrome [130], intrauterine growth restriction, and pre-term birth [131]. However, its preconception use is less studied. Recently, the impact of folic acid supplementation was investigated regarding the earlier stages of female reproductive physiology, in particular its role in folliculogenesis [119]. During the preovulatory stage, folic acid decreased the proportion of developmentally delayed embryos in a mouse model [132] and increased glutathione synthesis at the oocyte level in a rat model, although it was unable to revert the altered expression pattern of genes related to mitochondrial function and dynamics [133].

Use of Folic Acid in Infertility

In humans, folate and homocysteine are present in the follicular fluid [134], and these levels correlate with their blood concentrations [135]. Moreover, folic acid supplementation increases serum folate concentration and reduces serum hyperhomocysteinemia [135], exerting the same effect at the follicular level. A negative correlation was found between homocysteine levels in the follicular fluid and oocyte maturity [127], as well as in vitro day-3 embryo quality [136]. Similar results were obtained in a recent study conducted in PCOS patients, where negative correlations between homocysteine concentrations and fertilization rates, as well as oocyte and embryo quality, were observed [137]. Furthermore, higher folate intake was related to higher implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth rates [138].

Supplemental folic acid may improve ART outcomes and is favored over food-based sources due to lower amounts of bioavailable folate in food [139]. However, literature evaluating the impact of folate levels on reproduction analyze the effects of different concentrations within the normal dietary intake range, and folic acid supplementation studies are scarce. A prospective study conducted in women with unexplained infertility found no difference in clinical pregnancy rates (32.8% users vs. 35.7% non-users) and live birth rates (24.1% users vs. 31.0% non-users) after folic acid supplementation, even though folate blood levels were increased [140].

Therefore, a diet rich in folate is essential to achieve good pregnancy outcomes. Its antioxidant properties may have an important impact in folliculogenesis and early embryo development, although folate has multiple other functions that may also assist pregnancy. However, there are no clinical trials confirming its therapeutic advantages as an antioxidant supplement to benefit infertility treatment or its potential to enhance oocyte mitochondrial function.

2.4.3. Ascorbic Acid

Ascorbic acid, also known as vitamin C, is a powerful antioxidant that scavenges free radicals [141]. Its addition to culture and vitrification/warming media significantly improves the quality and survival rates of porcine cryopreserved embryos by regulating some crucial genes implicated in mitochondrial redox status [142]. Despite this, ascorbic acid supplementation to fertilization and conventional culture media did not exert any significant beneficial effect on maturation, fertilization, or embryo development parameters [143].

Use of Ascorbic Acid in Infertility

In humans, ascorbic acid supplementation significantly increased serum and follicular fluid ascorbic acid levels [144,145,146]. However, no differences in implantation or clinical pregnancy rates were found after ascorbic acid supplementation in women undergoing an IVF procedure, either during hormonal ovarian stimulation [144] or during the luteal phase [145]. In addition, this therapy was incapable of reducing oxidative stress markers in women with endometriosis after two months of treatment [146]. Therefore, although promising, vitamin C supplementation in infertile patients has yet to show a beneficial effect on fertility. Further clinical trials are needed to confirm preliminary results.

2.4.4. Vitamin D

Vitamin D plays a crucial role in dietary calcium absorption. In the reproductive field, vitamin D deficiency has been suggested to impact reproductive performance [147], but the evidence is not conclusive. Its potential antioxidant effect in the human female gamete has not been investigated. Currently, an RCT is being conducted in which follicular fluid and cumulus cells samples will be processed in order to evaluate the effect of vitamin D supplementation on oocyte quality, although the main primary endpoint is the clinical pregnancy rate [148]. Because vitamin D shows antioxidant properties [149] and the ability to improve mitochondrial function in other tissues [150], it could become an antioxidant treatment in the future, although its implications as an antioxidant at the oocyte molecular level need to be elucidated.

2.4.5. Vitamin E

Vitamin E is an essential antioxidant mainly found in high-fat vegetable products, and α–tocopherol is its most common form [151]. Its main role is the protection of cell membranes from oxidative damage by reaction with lipid radicals produced in the lipid peroxidation chain reaction [5].

Culture media supplementation with vitamin E increased the blastocyst development rate in a bovine model, presumably by protecting from ROS [152]. Similar results were found in a mouse model, although with less benefit compared to vitamin C supplementation [153]. Interestingly, combined oral supplementation with vitamins C and E successfully prevented ovarian aging in a mouse model [154].

Use of Vitamin E in Infertility

Bahadori et al. described several vitamin E concentration intervals related to higher human oocyte and embryo quality. Follicular fluid vitamin E levels in the ranges 0.35–1 mg/dL and 1.5–2 mg/dL were related to higher oocyte maturation rates (89.2% and 84.9%, respectively, vs. 69.6% in 1–1.5 mg/dL and 76.7% in 2–7.4 mg/dL; p = 0.002) while serum vitamin E levels in the range 10–15 mg/dL were related to a higher proportion of high-quality embryos (87.5% vs. 46.2 in 1–5 mg/dL, 54.9% in 5–10 mg/dL, 42.9% in 15–20 mg/dL; p = 0.007). However, no significant relationship between serum vitamin E levels and oocyte maturation was found, nor was there a correlation between follicular fluid vitamin E levels and embryo quality [155].

A recent RCT showed that the concomitant administration of vitamin E and vitamin D to women with PCOS was associated with higher implantation (35.1% vs. 8.6%; p < 0.001), pregnancy (69.0% vs. 25.8%; p < 0.001), and clinical pregnancy rates (62.1% vs. 22.6%; p = 0.002) compared to a control group [156]. However, these outcomes were not associated with an antioxidant mechanism. Therefore, the findings of this trial do not support the use of vitamins D and E as a dual antioxidant treatment in IVF, and further research is needed to determine whether the antioxidant mechanism of vitamin E can improve mitochondrial oocyte function.

2.5. Antioxidants in Combination

Antioxidants can be supplied alone or in combination, and different cocktails of these molecules were evaluated for their potential to improve oocyte quality both in animal [157,158] and human studies [159,160]. Providing antioxidants in combination may more closely resemble in vivo conditions, where the molecules participate in a complex system with multi-faced interactions and feedback mechanisms [161]. It is important that antioxidants be evaluated both alone and in combination to distinguish which specific antioxidant is responsible for certain benefits.

2.6. Other Antioxidant Mechanisms

The molecules described in this review have been evaluated for their potential to improve mitochondrial function in reproduction, though many additional molecules may also serve this purpose. Many molecules have antioxidant properties, including growth hormone [162], progesterone [163], and curcumin [164], which successfully reduce oxidative stress in the animal model; only the mechanism of action for growth hormone is suggested to be related to mitochondrial activity improvement [162]. In addition, putrescine supplementation improves oocyte quality and reproductive performance in aged mice [165] and is related to improved mitochondrial activity [166]. Because human granulosa cells from aged follicles present periovulatory putrescine deficiency [167], putrescine supplementation is suggested as a novel therapy to restore human ovarian function.

Another method of inducing the antioxidant effect is caloric restriction (CR). CR consists of limiting the daily diet to 25–50% of the normal diet. CR extended the lifespan and delayed aging in rodents [168]. In addition, CR can improve fertility and prolong reproductive life by delaying the process of ovarian aging [169]. However, its implementation is not easy in practice, and there are alternative substances that can induce the same effects [170]. For instance, metformin decreases the production of hepatic glucose by inhibiting the mitochondrial ETC complex I; thus, it mimics CR effects while reducing ROS production [171].

Other compounds enhance reproductive performance, though their potential antioxidant role has not been evaluated. For example, vitamin D [172] and myo-inositol [173] administration to infertile patients undergoing IVF treatments improved clinical outcomes. The addition of myo-inositol to other molecules with proven antioxidant properties also showed promising results in PCOS [174] and IVF patients [175].

In sum, infertility therapy based on antioxidant supplementation is continuously evolving, and new applications of molecules may be adopted to keep oxidative stress in balance. This review covers antioxidants already described in the literature but constitutes only a subset of all molecules with antioxidant properties available. Therefore, continued research in this area is critical to the development of antioxidant therapies and applications.

3. Conclusions

Antioxidants are molecules that are easily obtained from natural sources. Their mechanisms of action are diverse, but they typically enhance mitochondrial function or directly scavenge free radicals, which in turn protects mitochondria and other cellular components from oxidative stress. Given the crucial role of mitochondrial activity in oocyte maturation, fertilization, and embryo development, antioxidants may improve ART outcomes by improving oocyte quality.

In ART, antioxidant supplementation can be prescribed as an oral pre-treatment or as an adjuvant in the media during in vitro culture, although the extent of its effects have not been fully elucidated. Indeed, the majority of studies described throughout this review evaluate the indirect consequences of antioxidant supplementation on oocyte quality, evidenced by endpoints such as oocyte maturation, aneuploidy, and pregnancy rates, which may or may not be related to improved mitochondrial function. Although the direct relationship between antioxidant support and improved mitochondrial function is likely, further studies are needed to fully evaluate the consequence of antioxidant treatment on specific mitochondrial parameters, such as mitochondrial membrane potential, morphology, and distribution, as well as oxidative stress markers. In addition, there is no consensus on the optimal dose and duration of treatment, so further evaluation of these parameters is necessary before clinical application of antioxidant strategies.

Although antioxidant therapy is a promising and safe therapy, well-designed human clinical trials are needed before it is incorporated into routine clinical practice. The population that can benefit from their use must also be clearly defined, and their short- and long-term safety must be evaluated. Further, the mechanisms of each antioxidant’s action at the molecular level and the administration protocol must be clearly defined.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.-V. and E.L.; methodology, C.R.-V.; validation, C.R.-V. and E.L.; investigation, C.R.-V.; resources, C.R.-V. and E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.-V. and E.L.; writing—review and editing, C.R-V. and E.L.; supervision, E.L.; project administration, E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

C.R.V. received a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities in 2019 for the National Programme for Training University Lecturers (FPU). The authors would like to thank Mario Fernandez Bernal for drawing the original figures in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. During the past 12 months, Dr Labarta has received honoraria from Angelini/IBSA, Merck, MSD and Ferring Pharmaceuticals for lecturing. She received a grant from Ferring in 2020, and has provided consultancy services for MSD and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.-B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K.J.A. Mitochondrial Free Radical Generation, Oxidative Stress, and Aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 29, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: An updated overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 651–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin and its metabolites vs oxidative stress: From individual actions to collective protection. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norbury, C.J.; Zhivotovsky, B. DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2797–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Kim, C.N.; Yang, J.; Jemmerson, R.; Wang, X. Induction of Apoptotic Program in Cell-Free Extracts: Requirement for dATP and Cytochrome c. Cell 1996, 86, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Marcillat, O.; Giulivi, C.; Ernster, L.; Davies, K.J.A. The oxidative inactivation of mitochondrial electron transport chain components and ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 16330–16336. [Google Scholar]

- Babayev, E.; Seli, E. Oocyte mitochondrial function and reproduction. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 27, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, J.F.; Saretzki, G.; Von Zglinicki, T. DNA damage in telomeres and mitochondria during cellular senescence: Is there a connection? Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7505–7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, R.S.; Nemoto, S.; Finkel, T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 2005, 120, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.T.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 2006, 443, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lisa, F.; Kaludercic, N.; Carpi, A.; Menabò, R.; Giorgio, M. Mitochondria and vascular pathology. Pharmacol. Rep. 2009, 61, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Panloup, P.; Boucret, L.; de la Barca, J.M.C.; Desquiret-Dumas, V.; Ferré-L’Hotellier1, V.; Morinière, C.; Descamps, P.; Procaccio, V.; Reynier, P. Ovarian ageing: The role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Wang, D.H.; Zou, X.Y.; Xu, C.M. Mitochondrial functions on oocytes and preimplantation embryos. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2009, 10, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Kuhn, C.; Kolben, T.; Ma, Z.; Lin, P.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; von Schönfeldt, V. Early life oxidative stress and long-lasting cardiovascular effects on offspring conceived by assisted reproductive technologies: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarín, J.J. Potential effects of age-associated oxidative stress on mammalian oocytes/embryos. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1996, 2, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngô, C.; Chéreau, C.; Nicco, C.; Weill, B.; Chapron, C.; Batteux, F. Reactive oxygen species controls endometriosis progression. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, L. Polycystic ovary syndrome and mitochondrial dysfunction. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2019, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiosano, D.; Mears, J.A.; Buchner, D.A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Primary Ovarian Insufficiency. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 2353–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampiao, F. Free radicals generation in an in vitro fertilization setting and how to minimize them. World J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Montfoort, A.P.A.; Arts, E.G.J.M.; Wijnandts, L.; Sluijmer, A.; Pelinck, M.-J.; Land, J.A.; Van Echten-Arends, J. Reduced oxygen concentration during human IVF culture improves embryo utilization and cumulative pregnancy rates per cycle. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoz036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Will, M.A.; Clark, N.A.; Swain, J.E. Biological pH buffers in IVF: Help or hindrance to success. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2011, 28, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo, A.; Bellver, J.; Domingo, J.; Pérez, S.; Crespo, J.; Pellicer, A.; Remohí, J. New options in assisted reproduction technology: The Cryotop method of oocyte vitrification. RBMO 2008, 17, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronopoulou, E.; Harper, J.C. IVF culture media: Past, present and future. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentov, Y.; Hannam, T.; Jurisicova, A.; Esfandiari, N.; Casper, R.F. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation and Oocyte Aneuploidy in Women Undergoing IVF-ICSI Treatment. Clin. Med. Insights Reprod. Health 2014, 8, CMRH.S14681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, A.; Kuroda, K.; Ikemoto, Y.; Ozaki, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Nojiri, S.; Takeda, S.; Sugiyama, R. Influence of resveratrol supplementation on IVF–embryo transfer cycle outcomes. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 39, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryilmaz, O.G.; Devran, A.; Sarikaya, E.; Aksakal, F.N.; Mollamahmutoğlu, L.; Cicek, N. Melatonin improves the oocyte and the embryo in IVF patients with sleep disturbances, but does not improve the sleeping problems. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2011, 28, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showell, M.G.; Mackenzie-Proctor, R.; Jordan, V.; Hart, R.J. Antioxidants for female subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, 1–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showell, M.G.; Mackenzie-Proctor, R.; Jordan, V.; Hart, R.J. Antioxidants for female subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcaniolo, D.; Favilla, V.; Tiscione, D.; Pisano, F.; Bozzini, G.; Creta, M.; Gentile, G.; Fabris, F.M.; Pavan, N.; Veneziano, I.A.; et al. Is there a place for nutritional supplements in the treatment of idiopathic male infertility? Arch. Ital. di Urol. e Androl. 2014, 86, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadros Gomes, B.A.; Bastos Silva, J.P.; Rodrigues Romeiro, C.F.; dos Santos, S.M.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Gonçalves, P.R.; Sakai, J.T.; Santos Mendes, P.F.; Pompeu Varela, E.L.; Monteiro, M.C. Neuroprotective mechanisms of resveratrol in Alzheimer’s disease: Role of SIRT1. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Jiang, X.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y. Benefits of Vitamins in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.X.; Rosales-Corral, S.; Galano, A.; Zhou, X.J.; Xu, B. Mitochondria: Central organelles for melatonins antioxidant and anti-Aging actions. Molecules 2018, 23, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.K.; Billings, F.T.; Claessens, A.J.; Roshanravan, B.; Linke, L.; Sundell, M.B.; Ahmad, S.; Shao, B.; Shen, D.D.; Ikizler, T.A.; et al. Coenzyme Q10 dose-escalation study in hemodialysis patients: Safety, tolerability, and effect on oxidative stress Dialysis and Transplantation. BMC Nephrol. 2015, 16, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raizner, A.E. Coenzyme Q10. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J. 2019, 15, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.M.; Smith, R.A.J.; Murphy, M.P. Antioxidant and prooxidant properties of mitochondrial Coenzyme Q. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 423, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.V.; Horn, P.S.; Tang, P.H.; Morrison, J.A.; Miles, L.; Degrauw, T.; Pesce, A.J. Age-related changes in plasma coenzyme Q10 concentrations and redox state in apparently healthy children and adults. Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 347, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Meir, A.; Burstein, E.; Borrego-Alvarez, A.; Chong, J.; Wong, E.; Yavorska, T.; Naranian, T.; Chi, M.; Wang, Y.; Bentov, Y.; et al. Coenzyme Q10 restores oocyte mitochondrial function and fertility during reproductive aging. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, C.E.; Boudoures, A.; Zhang, W.; Drury, A.; Moley, K.H. Obesity-induced oocyte mitochondrial defects are partially prevented and rescued by supplementation with co-enzyme Q10 in a mouse model. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2090–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornos Carneiro, M.F.; Shin, N.; Karthikraj, R.; Barbosa, F.; Kannan, K.; Colaiácovo, M.P. Antioxidant CoQ10 restores fertility by rescuing bisphenol a-induced oxidative DNA damage in the caenorhabditis elegans germline. Genetics 2020, 214, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, P.; Fıçıcıoğlu, C.; Kizilkale, O.; Yesiladali, M.; Tok, O.E.; Ozkan, F.; Esrefoglu, M. Can Coenzyme Q10 supplementation protect the ovarian reserve against oxidative damage? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2016, 33, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; ShiYang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Z.; Xiong, B. Coenzyme Q10 ameliorates the quality of postovulatory aged oocytes by suppressing DNA damage and apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 143, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.J.; Zhou, W.; Nie, Z.W.; Zhou, D.; Xu, Y.N.; Ock, S.A.; Yan, C.G.; Cui, X.S. Ubiquinol-10 delays postovulatory oocyte aging by improving mitochondrial renewal in pigs. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 1256–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Meir, A.; Kim, K.; McQuaid, R.; Esfandiari, N.; Bentov, Y.; Casper, R.F.; Jurisicova, A. Co-enzyme q10 supplementation rescues cumulus cells dysfunction in a maternal aging model. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarsu, S.; Gode, F.; Isik, A.Z.; Dikmen, Z.G.; Tekindal, M.A. The association between coenzyme Q10 concentrations in follicular fluid with embryo morphokinetics and pregnancy rate in assisted reproductive techniques. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2017, 34, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannubilo, S.R.; Orlando, P.; Silvestri, S.; Cirilli, I.; Marcheggiani, F.; Ciavattini, A.; Tiano, L. CoQ10 supplementation in patients undergoing IVF-ET: The relationship with follicular fluid content and oocyte maturity. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Nisenblat, V.; Lu, C.; Li, R.; Qiao, J.; Zhen, X.; Wang, S. Pretreatment with coenzyme Q10 improves ovarian response and embryo quality in low-prognosis young women with decreased ovarian reserve: A randomized controlled trial. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florou, P.; Anagnostis, P.; Theocharis, P.; Chourdakis, M.; Goulis, D.G. Does coenzyme Q10 supplementation improve fertility outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology procedures? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Refaeey, A.; Selem, A.; Badawy, A. Combined coenzyme Q10 and clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction in clomiphene-citrate-resistant polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2014, 29, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhasan, M.K.; Li, Q.; Dai, J.; Abu-Soud, H.M.; Puscheck, E.E.; Rappolee, D.A. CoQ10 increases mitochondrial mass and polarization, ATP and Oct4 potency levels, and bovine oocyte MII during IVM while decreasing AMPK activity and oocyte death. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2017, 34, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maside, C.; Martinez, C.A.; Cambra, J.M.; Lucas, X.; Martinez, E.A.; Gil, M.A.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H.; Parrilla, I.; Cuello, C. Supplementation with exogenous coenzyme Q10 to media for in vitro maturation and embryo culture fails to promote the developmental competence of porcine embryos. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2019, 54, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Cai, L.; Hu, M.; Wang, J.; Xie, J.; Xing, Y.; Shen, J.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.J.; Liu, J. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation of human oocyte in vitro maturation reduces postmeiotic aneuploidies. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kile, R.; Logsdon, D.M.; Nathanson, C.; McCormick, S.; Schoolcraft, W.B.; Krisher, R.L. Mitochondrial support of embryos from women of advanced maternal age during ART. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, I.; Duleba, A.J. Ovarian actions of resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1348, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.R.; Lucio, M.; Lima, J.L.C.; Reis, S. Resveratrol in Medicinal Chemistry: A Critical Review of its Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Delivery, and Membrane Interactions. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 1663–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, C.I.; Nori, S.L. Complementary therapy in polycystic ovary syndrome. Transl. Med. @ UniSa 2014, 9, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahdouz Mohammadi, R.; Arablou, T. Resveratrol and endometriosis: In vitro and animal studies and underlying mechanisms (Review). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.; SH Yang, Y.C.; Chin, Y.T.; Chou, S.Y.; Chen, Y.R.; Shih, Y.J.; Whang-Peng, J.; Changou, C.A.; Liu, H.L.; Lin, S.J.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits human leiomyoma cell proliferation via crosstalk between integrin αvβ3 and IGF-1R. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 120, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra, M.T.; Smith, B.C.; Denu, J.M. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17187–17195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Emidio, G.; Falone, S.; Vitti, M.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Vento, M.; Di Pietro, C.; Amicarelli, F.; Tatone, C. SIRT1 signalling protects mouse oocytes against oxidative stress and is deregulated during aging. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.G.; Luo, L.L.; Xu, J.J.; Zhuang, X.L.; Kong, X.X.; Fu, Y.C. Effects of plant polyphenols on ovarian follicular reserve in aging rats. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 88, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Yin, Y.; Ye, X.; Zeng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Keefe, D.L.; Liu, L. Resveratrol protects against age-associated infertility in mice. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.R.; Uddin, S.; Bu, R.; Khan, O.S.; Ahmed, S.O.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Kuraya, K.S. Resveratrol suppresses constitutive activation of AKT via generation of ROS and induces apoptosis in diffuse large B cell lymphoma cell lines. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, S.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Resveratrol Suppresses TNF-Induced Activation of Nuclear Transcription Factors NF-κB, Activator Protein-1, and Apoptosis: Potential Role of Reactive Oxygen Intermediates and Lipid Peroxidation. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 6509–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Liu, L. Mechanism of resveratrol in improving ovarian function in a rat model of premature ovarian insufficiency. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2018, 44, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ma, L.; Xue, L.; Ye, W.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Jin, Y.; Qin1, X.; Chen, D.; Tang, W.; et al. Resveratrol alleviates chemotherapy-induced oogonial stem cell apoptosis and ovarian aging in mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.J.; Sun, A.G.; Zhao, S.G.; Liu, H.; Ma, S.Y.; Li, M.; Huai, Y.X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, H. Bin Resveratrol improves in vitro maturation of oocytes in aged mice and humans. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Kawahara-Miki, R.; Kawana, H.; Shirasuna, K.; Kuwayama, T.; Iwata, H. Resveratrol-induced mitochondrial synthesis and autophagy in oocytes derived from early antral follicles of aged cows. J. Reprod. Dev. 2015, 61, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabihi, A.; Shabankareh, H.K.; Hajarian, H.; Foroutanifar, S. Resveratrol addition to in vitro maturation and in vitro culture media enhances developmental competence of sheep embryos. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2019, 68, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.H.; Villanueva, J.A.; Cress, A.B.; Duleba, A.J. Effects of resveratrol on proliferation and apoptosis in rat ovarian theca-interstitial cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 16, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, I.; Villanueva, J.A.; Wong, D.H.; Cress, A.B.; Sokalska, A.; Stanley, S.D.; Duleba, A.J. Resveratrol reduces steroidogenesis in rat ovarian theca-interstitial cells: The role of inhibition of Akt/ PKB signaling pathway. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4019–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergenoglu, M.; Yildirim, N.; Yildirim, A.G.S.; Yeniel, O.; Erbas, O.; Yavasoglu, A.; Taskiran, D.; Karadadas, N. Effects of resveratrol on ovarian morphology, plasma anti-mullerian hormone, IGF-1 levels, and oxidative stress parameters in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 22, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, I.; Wong, D.H.; Villanueva, J.A.; Cress, A.B.; Sokalska, A.; Stanley, S.D.; Duleba, A.J. Effects of resveratrol on growth and function of rat ovarian granulosa cells. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 1563–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.W.; King, A.E.; Critchley, H.O.D. Cytokine control in human endometrium. Reproduction 2001, 121, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, A.; Kuroda, K. Preconception resveratrol intake against infertility: Friend or foe? Reprod. Med. Biol. 2020, 19, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszewska, B.; Wrotyńska-Barczyńska, J.; Spaczynski, R.Z.; Pawelczyk, L.; Duleba, A.J. Effects of Resveratrol on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Double-blind, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 4322–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramrezaie, M.; Amidi, F.; Aleyasin, A.; Saremi, A.T.; Aghahoseini, M.; Brenjian, S.; Khodarahmian, M.; Pooladi, A. Effects of resveratrol on VEGF & HIF1 genes expression in granulosa cells in the angiogenesis pathway and laboratory parameters of polycystic ovary syndrome: A triple-blind randomized clinical trial. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boocock, D.J.; Faust, G.E.S.; Patel, K.R.; Schinas, A.M.; Brown, V.A.; Ducharme, M.P.; Booth, T.D.; Crowell, J.A.; Perloff, M.; Gescher, A.J.; et al. Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar do Amaral, F.; Cipolla-Neto, J. A brief review about melatonin, a pineal hormone. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 62, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeland, R. Antioxidative protection by melatonin: Multiplicity of mechanisms from radical detoxification to radical avoidance. Endocrine 2005, 27, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Dong, Y.; Fan, C.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Di, S.; Yue, L.; Liang, G.; et al. Melatonin prevents cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction via a SIRT1-dependent mechanism during ischemic-stroke in mice. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 58, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuffa, G.G.A.; Fioruci-Fontanelli, B.A.; Mendes, L.O.; Ferreira Seiva, F.R.; Martinez, M.; Fávaro, W.J.; Domeniconi, R.F.; Pinheiro, P.F.F.; Delazari dos Santos, L.; Martinez, F.E. Melatonin attenuates the TLR4-mediated inflammatory response through MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways in an in vivo model of ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliaferri, V.; Romualdi, D.; Scarinci, E.; De Cicco, S.; Di Florio, C.; Immediata, V.; Tropea, A.; Santarsiero, C.M.; Lanzone, A.; Apa, R. Melatonin Treatment May Be Able to Restore Menstrual Cyclicity in Women with PCOS: A Pilot Study. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 25, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnacci, A. Melatonin in relation to physiology in adult humans. J. Pineal Res. 1996, 21, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Tong, J.; Li, W.P.; Chen, Z.J.; Zhang, C. Melatonin concentration in follicular fluid is correlated with antral follicle count (AFC) and in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2018, 34, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J. The ageing pineal gland and its physiological consequences. BioEssays 1992, 14, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakkuri, O.; Kivelä, A.; Leppäluoto, J.; Valtonen, M.; Kauppila, A. Decrease in melatonin precedes follicle-stimulating hormone increase during perimenopause. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1996, 135, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Peng, W.; Yin, S.; Zhao, J.; Fu, B.; Zhang, J.; Mao, T.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin improves age-induced fertility decline and attenuates ovarian mitochondrial oxidative stress in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasaki, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Tamura, H.; Shimamura, K.; Morioka, H. Melatonin as a new drug for improving oocyte quality. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2003, 2, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, H.; Takasaki, A.; Miwa, I.; Taniguchi, K.; Maekawa, R.; Asada, H.; Taketani, T.; Matsuoka, A.; Yamagata, Y.; Shimamura, K.; et al. Oxidative stress impairs oocyte quality and melatonin protects oocytes from free radical damage and improves fertilization rate. J. Pineal Res. 2008, 44, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batioǧlu, A.S.; Şahin, U.; Grlek, B.; Öztrk, N.; Ünsal, E. The efficacy of melatonin administration on oocyte quality. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2012, 28, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwertner, A.; Conceição Dos Santos, C.C.; Costa, G.D.; Deitos, A.; De Souza, A.; De Souza, I.C.C.; Torres, I.L.S.; Da Cunha Filho, J.S.L.; Caumo, W. Efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of endometriosis: A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2013, 154, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aversa, S.; Pellegrino, S.; Barberi, I.; Reiter, R.J.; Gitto, E. Potential utility of melatonin as an antioxidant during pregnancy and in the perinatal period. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattoraj, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Basu, D.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Maitra, S.K. Melatonin accelerates maturation inducing hormone (MIH): Induced oocyte maturation in carps. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2005, 140, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, S.; Wallace, E.M.; Vollenhoven, B.; Lolatgis, N.; Hope, N.; Wong, M.; Lawrence, M.; Lawrence, A.; Russell, C.; Leong, K.; et al. Melatonin in assisted reproductive technology: A pilot double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, J.; Macedo, M.; Lozano, G.; Ortiz, Á.; Rodríguez, C.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Bejarano, I. Impact of melatonin supplementation in women with unexplained infertility undergoing fertility treatment. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Ma, T.; Tao, J.; Zhu, K.; Song, Y.; et al. Mitochondria synthesize melatonin to ameliorate its function and improve mice oocyte’s quality under in vitro conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Osorio, N.; Kim, I.J.; Wang, H.; Kaya, A.; Memili, E. Melatonin increases cleavage rate of porcine preimplantation embryos in vitro. J. Pineal Res. 2007, 43, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Park, E.A.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, W.Y.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, W.S.; Cha, K.Y.; You Kim, S.; Lee, D.R.; Yoon, T.K. Does supplementation of in-vitro culture medium with melatonin improve IVF outcome in PCOS. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2013, 26, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, H.M.; Steel, A.E. Adverse events associated with oral administration of melatonin: A critical systematic review of clinical evidence. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 42, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genario, R.; Morello, E.; Bueno, A.A.; Santos, H.O. The usefulness of melatonin in the field of obstetrics and gynecology. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 147, 104337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palace, V.P.; Khaper, N.; Qin, Q.; Singal, P.K. Antioxidant potentials of vitamin A and carotenoids and their relevance to heart disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweigert, F.J.; Zucker, H. Concentrations of vitamin A, β-carotene and vitamin E in individual bovine follicles of different quality. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1988, 82, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves-Hoagland, R.L.; Hoagland, T.A.; Woody, C.O. Effect of β-Carotene and Vitamin A on Progesterone Production by Bovine Luteal Cells. J. Dairy Sci. 1988, 71, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Kitagawa, M.; Imai, H.; Yamada, M. The roles of vitamin A for cytoplasmic maturation of bovine oocytes. J. Reprod. Dev. 2005, 51, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livera, G.; Rouiller-Fabre, V.; Valla, J.; Habert, R. Effects of retinoids on the meiosis in the fetal rat ovary in culture. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2000, 165, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.H.; Dore, J.J.E.; Roberts, M.P.; Krishnan, R.; Hopkins, F.M.; Godkin, J.D. Expression and Cellular Localization of Retinol-Binding Protein Messenger Ribonucleic Acid in Bovine Blastocysts and Extraembryonic Membranes1. Biol. Reprod. 1993, 49, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Whaley, S.L.; Hedgpeth, V.S.; Farin, C.E.; Martus, N.S.; Jayes, F.C.L.; Britt, J.H. Influence of vitamin A injection before mating on oocyte development, follicular hormones, and ovulation in gilts fed high-energy diets. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 78, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, D.M.; Will, W.A.; Godkin, J.D. Retinol administration to superovulated ewes improves in vitro embryonic viability. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 60, 1483–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour, S.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Swelum, A.A.A.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Noreldin, A.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Al-Mutary, M.G.; Arif, M.; Hussein, E.S.O.S. The usefulness of retinoic acid supplementation during in vitro oocyte maturation for the in vitro embryo production of livestock: A review. Animals 2019, 9, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, C.; Díez, C.; Duque, P.; Prendes, J.M.; Rodríguez, A.; Goyache, F.; Fernández, I.; Facal, N.; Ikeda, S.; Alonso-Montes, C.; et al. Oocytes recovered from cows treated with retinol become unviable as blastocysts produced in vitro. Reproduction 2005, 129, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri, E.; Mahmoudi, R.; Bahadori, M.H.; Amiri, I. The Effect of Retinoic Acid on In vitro Maturation and Fertilization Rate of Mouse Germinal Vesicle Stage Oocytes. Cell J. 2011, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pauli, S.A.; Session, D.R.; Shang, W.; Easley, K.; Wieser, F.; Taylor, R.N.; Pierzchalski, K.; Napoli, J.L.; Kane, M.A.; Sidell, N. Analysis of follicular fluid retinoids in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: Retinoic acid influences embryo quality and is reduced in women with endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2013, 20, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, M.W.; Wu, J.; Pauli, S.A.; Kane, M.A.; Pierzchalski, K.; Session, D.R.; Woods, D.C.; Shang, W.; Taylor, R.N.; Sidell, N. A role for retinoids in human oocyte fertilization: Regulation of connexin 43 by retinoic acid in cumulus granulosa cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 21, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damdimopoulou, P.; Chiang, C.; Flaws, J.A. Retinoic acid signaling in ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis. Reprod. Toxicol. 2019, 87, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.M.; Bailey, R.; O’Connor, D.L. Folate. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpad, A.V.; Anand, P.; Dwarkanath, P.; Hsu, J.W.; Thomas, T.; Devi, S.; Thomas, A.; Mhaskar, R.; Jahoor, F. Whole body methionine kinetics, transmethylation, transulfuration and remethylation during pregnancy. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laanpere, M.; Altmäe, S.; Stavreus-Evers, A.; Nilsson, T.K.; Yngve, A.; Salumets, A. Folate-mediated one-carbon metabolism and its effect on female fertility and pregnancy viabilityn ure_266 99..113. Nutr. Rev. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bree, A.; Van Dusseldorp, M.; Brouwer, I.A.; Van Het Hof, K.H.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.M. Folate intake in Europe: Recommended, actual and desired intake. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 51, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P.F.; Bostom, A.G.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Rich, S.; Rosenberg, I.H.; Selhub, J. Determinants of plasma total homocysteine concentration in the Framingham Offspring cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edirimanne, V.E.R.; Woo, C.W.H.; Siow, Y.L.; Pierce, G.N.; Xie, J.Y.; Karmin, O. Homocysteine stimulates NADPH oxidase-mediated superoxide production leading to endothelial dysfunction in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2007, 85, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outinen, P.A.; Sood, S.K.; Pfeifer, S.I.; Pamidi, S.; Podor, T.J.; Li, J.; Weitz, J.I.; Austin, R.C. Homocysteine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and growth arrest leads to specific changes in gene expression in human vascular endothelial cells—PubMed. Blood 1999, 94, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willmott, M.; Bartosik, D.B.; Romanoff, E.B. The effect of folic acid on superovulation in the immature rat. J. Endocrinol. 1968, 41, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, D.; Das, K.C. Effect of folate deficiency on the reproductive organs of female rhesus monkeys: A cytomorphological and cytokinetic study. J. Nutr. 1982, 112, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, C.J.; Budiman, H.; Ruebsamen, H.; Nagel, D.; Lohse, P. Effects of the common 677C>T mutation of the 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene on ovarian responsiveness to recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2006, 55, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymański, W.; Kazdepka-Ziemińska, A. Effect of homocysteine concentration in follicular fluid on a degree of oocyte maturity. Gynekol. Pol. 2003, 74, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrazzi, E.; Tiso, G.; Di Martino, D. Folic acid versus 5- methyl tetrahydrofolate supplementation in pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 253, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]