Annurca Apple By-Products at Different Ripening Stages Inhibit AGE Formation and Protect Against AGE-Induced Cytotoxicity Through Antioxidant Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fruit Collection

2.3. Polyphenol Extraction and Characterization

2.4. AGEs’ Formation

2.5. Fluorescence Measurements

2.6. Cell Cultures and Treatments

2.7. MTT Assay

2.8. Trypan Blue Assay

2.9. Detection of Intracellular ROS

2.10. ABTS Assay

2.11. Immunoblotting

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Annurca Apple Extracts’ Effect on Insulin-AGE Formation

3.2. Annurca Apple Extracts’ Protective Effect in AGE-Induced Toxicity

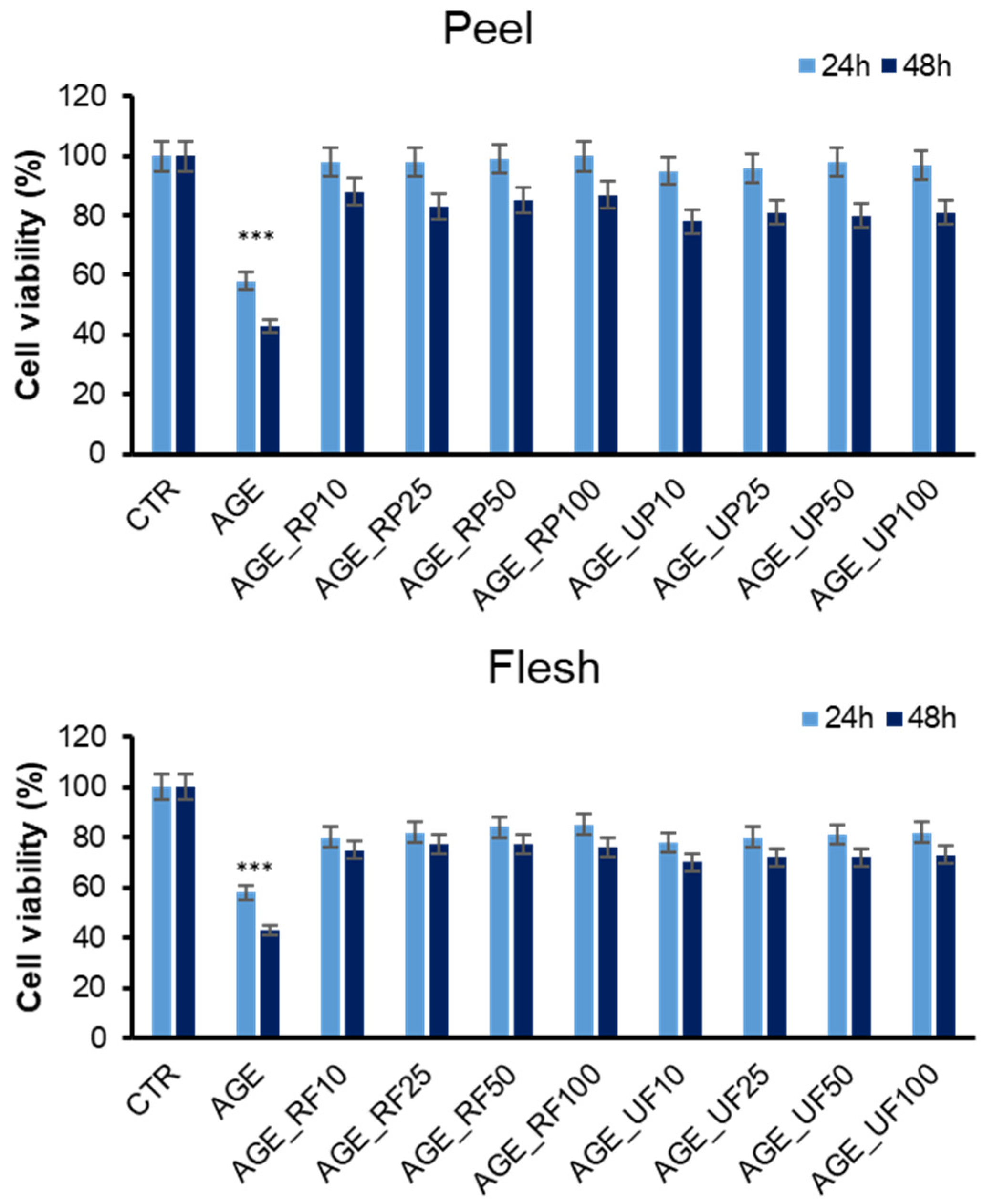

3.2.1. Evaluation of Cell Toxicity of Annurca Apple Extracts at Different Ripening Stages

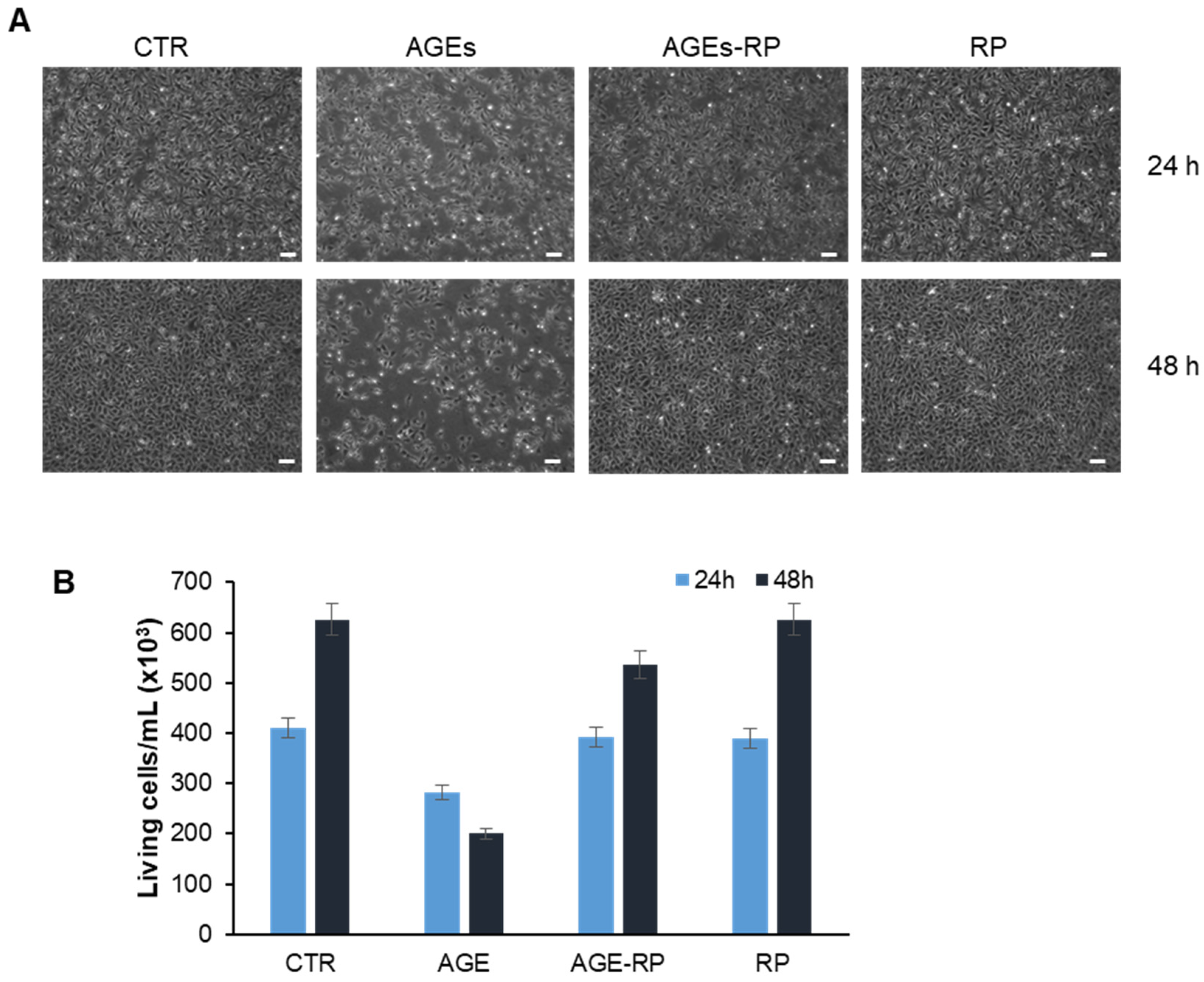

3.2.2. Annurca Apple Extracts’ Protective Effect in AGE-Induced Toxicity

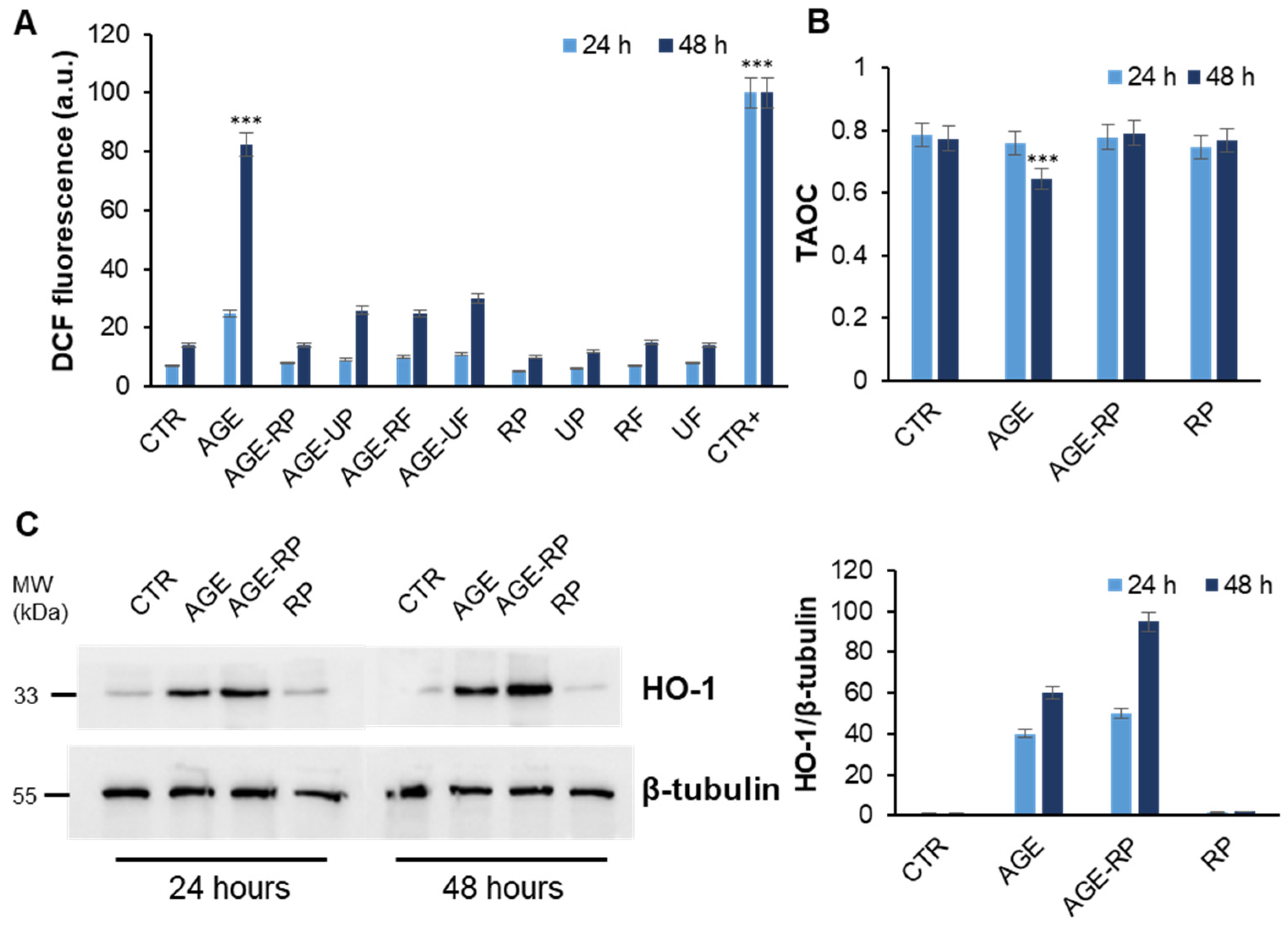

3.2.3. Annurca Apple Extracts’ Protective Effect in AGE-Induced Oxidative Stress

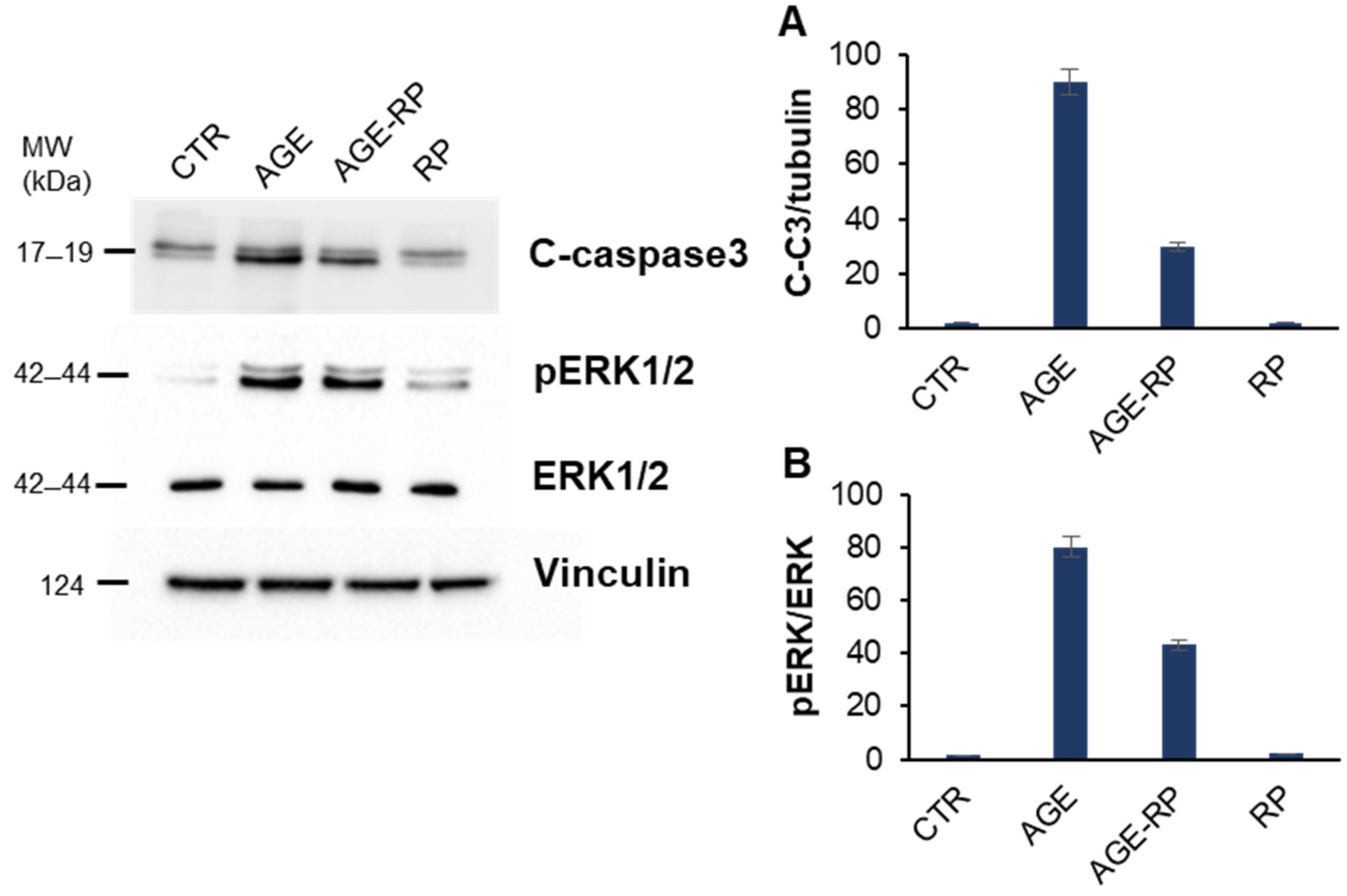

3.2.4. Annurca Apple Extracts’ Protective Effect in AGE-Induced Apoptosis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perrone, P.; Palmieri, S.; Piscopo, M.; Lettieri, G.; Eugelio, F.; Fanti, F.; D’Angelo, S. Antioxidant Activity of Annurca Apple By-Products at Different Ripening Stages: A Sustainable Valorization Approach. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratianni, F.; De Giulio, A.; Sada, A.; Nazzaro, F. Biochemical Characteristics and Biological Properties of Annurca Apple Cider. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; Moriello, C.; Alessio, N.; Manna, C.; D’Angelo, S. Cytoprotective Potential of Annurca Apple Polyphenols on Mercury-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Erythrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.; Martino, E.; Ilisso, C.P.; Bagarolo, M.L.; Porcelli, M.; Cacciapuoti, G. Pro-Oxidant and pro-Apoptotic Activity of Polyphenol Extract from Annurca Apple and Its Underlying Mechanisms in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Assante, R.; De Luca, M.; Ferraro, S.; Ferraro, A.; Ruvolo, A.; Natale, F.; Sotgiu, P.; Petitto, M.; Rizzo, R.; De Maria, U.; et al. Beneficial Metabolic Effect of a Nutraceuticals Combination (Monacolin K, Yeasted Red Rice, Polyphenolic Extract of Annurca Apple and Berberine) on Acquired Hypercholesterolemia: A Prospective Analysis. Metabolites 2021, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, A.; Nasso, R.; Di Maro, A.; Landi, N.; Chambery, A.; Russo, R.; D’Angelo, S.; Masullo, M.; Arcone, R. Identification and Characterization of Neuroprotective Properties of Thaumatin-like Protein 1a from Annurca Apple Flesh Polyphenol Extract. Nutrients 2024, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalzo, J.; Politi, A.; Peelegrini, N.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. Plant Genotype Affects Total Antioxidant Capacity and Phenolic Contents in Fruit. Nutrition 2005, 21, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; Landriani, L.; Patalano, R.; Meccariello, R.; D’Angelo, S. The Mediterranean Diet as a Model of Sustainability: Evidence-Based Insights into Health, Environment, and Culture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uceda, A.B.; Mariño, L.; Casasnovas, R.; Adrover, M. An Overview on Glycation: Molecular Mechanisms, Impact on Proteins, Pathogenesis, and Inhibition. Biophys. Rev. 2024, 16, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, J.; Bains, Y.; Guha, S.; Kahn, A.; Hall, D.; Bose, N.; Gugliucci, A.; Kapahi, P. The Role of Advanced Glycation End Products in Aging and Metabolic Diseases: Bridging Association and Causality. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariya, B.; Nagaraju, G.P. Advanced Glycation End Products in Diabetes, Cancer and Phytochemical Therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1614–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.-Y.; Lu, C.-H.; Wu, C.-H.; Li, K.-J.; Kuo, Y.-M.; Hsieh, S.-C.; Yu, C.-L. The Development of Maillard Reaction, and Advanced Glycation End Product (AGE)-Receptor for AGE (RAGE) Signaling Inhibitors as Novel Therapeutic Strategies for Patients with AGE-Related Diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristoforou, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Maratou, E.; Makrilakis, K. Association of Glycemic Indices (Hyperglycemia, Glucose Variability, and Hypoglycemia) with Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Complications. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 7489795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younus, H.; Anwar, S. Prevention of Non-Enzymatic Glycosylation (Glycation): Implication in the Treatment of Diabetic Complication. Int. J. Health Sci. 2016, 10, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Khan, S.; Almatroudi, A.; Khan, A.A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Rahmani, A.H. A Review on Mechanism of Inhibition of Advanced Glycation End Products Formation by Plant Derived Polyphenolic Compounds. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, R.; Bhadada, S.K. AGEs Accumulation with Vascular Complications, Glycemic Control and Metabolic Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Bone 2023, 176, 116884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalkwijk, C.G.; Stehouwer, C.D.A. Methylglyoxal, a Highly Reactive Dicarbonyl Compound, in Diabetes, Its Vascular Complications, and Other Age-Related Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 407–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Canto, E.; Ceriello, A.; Rydén, L.; Ferrini, M.; Hansen, T.B.; Schnell, O.; Standl, E.; Beulens, J.W. Diabetes as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor: An Overview of Global Trends of Macro and Micro Vascular Complications. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, E.D.; Wagner, E.; Nerlich, A.G. Increased Accumulation of the Glycoxidation Product N(Epsilon)-(Carboxymethyl)Lysine in Human Tissues in Diabetes and Aging. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengstie, M.A.; Chekol Abebe, E.; Behaile Teklemariam, A.; Tilahun Mulu, A.; Agidew, M.M.; Teshome Azezew, M.; Zewde, E.A.; Agegnehu Teshome, A. Endogenous Advanced Glycation End Products in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Diabetic Complications. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1002710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Rahman, T.; Ismail, A.A.-S.; Rashid, A.R.A. Diabetes-Associated Macrovasculopathy: Pathophysiology and Pathogenesis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2007, 9, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, E.J.; Liu, Z.; Khamaisi, M.; King, G.L.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.K.; Hughes, T.M.; Craft, S.; Freedman, B.I.; Bowden, D.W.; et al. Diabetic Microvascular Disease: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 4343–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groener, J.B.; Oikonomou, D.; Cheko, R.; Kender, Z.; Zemva, J.; Kihm, L.; Muckenthaler, M.; Peters, V.; Fleming, T.; Kopf, S.; et al. Methylglyoxal and Advanced Glycation End Products in Patients with Diabetes―What We Know so Far and the Missing Links. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019, 127, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chung, M.; Zhang, L.; Cai, S.; Pan, X.; Pan, Y. Targeting the AGEs-RAGE Axis: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions in Diabetic Wound Healing. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1667620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, S.; Roy, A.S. A Review on Prevention of Glycation of Proteins: Potential Therapeutic Substances to Mitigate the Severity of Diabetes Complications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 195, 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharpour Dil, F.; Ranjkesh, Z.; Goodarzi, M.T. A Systematic Review of Antiglycation Medicinal Plants. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, H.; Choudhary, M.I. Glycation, Carbonyl Stress and AGEs Inhibitors: A Patent Review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2015, 25, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinchansure, A.A.; Korwar, A.M.; Kulkarni, M.J.; Joshi, S.P. Recent Development of Plant Products with Anti-Glycation Activity: A Review. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 31113–31138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciantini, M.; Leri, M.; Nardiello, P.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. Olive Polyphenols: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, M.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Calabrese, V.; Calabrese, E.J.; Bucciantini, M.; Stefani, M. Healthy Effects of Plant Polyphenols: Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. Inhibitory Effect of Phenolic Compounds and Plant Extracts on the Formation of Advance Glycation End Products: A Comprehensive Review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.; Chen, T.; Deng, X.; Chen, N.; Li, R.; Ren, M.; Li, Y.; Luo, M.; Hao, H.; Wu, J.; et al. Polydatin Prevents Methylglyoxal-Induced Apoptosis through Reducing Oxidative Stress and Improving Mitochondrial Function in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 7180943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Dong, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Novel Advances in Inhibiting Advanced Glycation End Product Formation Using Natural Compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Zeng, M.; Luo, M. Metformin Prevents Methylglyoxal-Induced Apoptosis by Suppressing Oxidative Stress in Vitro and in Vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liccardo, M.; Sapio, L.; Perrella, S.; Sirangelo, I.; Iannuzzi, C. Genistein Prevents Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress Induced by Methylglyoxal in Endothelial Cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Scalzo, R.; Testoni, A.; Genna, A. ‘Annurca’ Apple Fruit, a Southern Italy Apple Cultivar: Textural Properties and Aroma Composition. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.M.A.; Lages, A.; Gomes, R.A.; Neves, H.; Família, C.; Coelho, A.V.; Quintas, A. Insulin Glycation by Methylglyoxal Results in Native-like Aggregation and Inhibition of Fibril Formation. BMC Biochem. 2011, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, J.R.; McKillop, A.M.; Mooney, M.H.; O’Harte, F.P.M.; Bell, P.M.; Flatt, P.R. Demonstration of Increased Concentrations of Circulating Glycated Insulin in Human Type 2 Diabetes Using a Novel and Specific Radioimmunoassay. Diabetologia 2003, 46, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.J.; Boyd, A.C.; O’Harte, F.P.M.; McKillop, A.M.; Wiggam, M.I.; Mooney, M.H.; McCluskey, J.T.; Lindsay, J.R.; Ennis, C.N.; Gamble, R.; et al. Demonstration of Glycated Insulin in Human Diabetic Plasma and Decreased Biological Activity Assessed by Euglycemic-Hyperinsulinemic Clamp Technique in Humans. Diabetes 2003, 52, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Olson, D.J.H.; Ross, A.R.S.; Wu, L. Structural and Functional Changes in Human Insulin Induced by Methylglyoxal. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1555–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirangelo, I.; Borriello, M.; Liccardo, M.; Scafuro, M.; Russo, P.; Iannuzzi, C. Hydroxytyrosol Selectively Affects Non-Enzymatic Glycation in Human Insulin and Protects by AGEs Cytotoxicity. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiacevich, S.B.; Pilar Buera, M. A Critical Evaluation of Fluorescence as a Potential Marker for the Maillard Reaction. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubitosa, F.; Fraternale, D.; Benayada, L.; De Bellis, R.; Gorassini, A.; Saltarelli, R.; Donati Zeppa, S.; Potenza, L. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Genoprotective Effects of Callus Cultures Obtained from the Pulp of Malus pumila cv Miller (Annurca Campana Apple). Foods 2024, 13, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirpe, M.; Palermo, V.; Bianchi, M.M.; Silvestri, R.; Falcone, C.; Tenore, G.; Novellino, E.; Mazzoni, C. Annurca Apple (M. Pumila Miller cv Annurca) Extracts Act against Stress and Ageing in S. cerevisiae Yeast Cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóbon-Velasco, J.C.; Cuevas, E.; Torres-Ramos, M.A. Receptor for AGEs (RAGE) as Mediator of NF-kB Pathway Activation in Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2014, 13, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soman, S.; Raju, R.; Sandhya, V.K.; Advani, J.; Khan, A.A.; Harsha, H.C.; Prasad, T.S.K.; Sudhakaran, P.R.; Pandey, A.; Adishesha, P.K. A Multicellular Signal Transduction Network of AGE/RAGE Signaling. J. Cell. Commun. Signal 2013, 7, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaito, A.; Aramouni, K.; Assaf, R.; Parenti, A.; Orekhov, A.; Yazbi, A.E.; Pintus, G.; Eid, A.H. Oxidative Stress-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2022, 27, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darenskaya, M.A.; Kolesnikova, L.I.; Kolesnikov, S.I. Oxidative Stress: Pathogenetic Role in Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications and Therapeutic Approaches to Correction. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 171, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notariale, R.; Moriello, C.; Alessio, N.; Del Vecchio, V.; Mele, L.; Perrone, P.; Manna, C. Protective Effect of Hydroxytyrosol against Hyperglycemia-Induced Phosphatidylserine Exposure in Human Erythrocytes: Focus on Dysregulation of Calcium Homeostasis and Redox Balance. Redox Biol. 2025, 85, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefarelli, G.; D’Abrosca, B.; Fiorentino, A.; Izzo, A.; Mastellone, C.; Pacifico, S.; Piscopo, V. Free-Radical-Scavenging and Antioxidant Activities of Secondary Metabolites from Reddened cv. Annurca Apple Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Mel’nikova, T.I.; Porozov, Y.B.; Terentiev, A.A. Oxidative Stress and Advanced Lipoxidation and Glycation End Products (ALEs and AGEs) in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 3085756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, X.; He, X.; Xing, Y.; Jiang, B.; Xiu, Z.; Bao, Y.; Dong, Y. Protective Effect of Flavonoids against Methylglyox-al-Induced Oxidative Stress in PC-12 Neuroblastoma Cells and Its Structure-Activity Relationships. Molecules 2022, 27, 7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Chen, W.; Chen, B.; Li, X. Resveratrol Promotes Diabetic Wound Healing by Inhibiting Ferropto-sis in Vascular Endothelial Cells. Burns 2024, 50, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martati, E.; Wang, H.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Zheng, L. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) and in Vitro and in Vivo Ap-proaches to Study Their Mechanisms of Action and the Protective Properties of Natural Compounds. Phytomedicine 2026, 150, 157772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.; Wu, X.; Liu, R.H. Antioxidant Activity of Apple Peels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhipa, A.S.; Borse, S.P.; Baksi, R.; Lalotra, S.; Nivsarkar, M. Targeting Receptors of Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE): Preventing Diabetes Induced Cancer and Diabetic Complications. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriello, M.; Iannuzzi, C.; Sirangelo, I. Pinocembrin Protects from AGE-Induced Cytotoxicity and Inhibits Non-Enzymatic Glycation in Human Insulin. Cells 2019, 8, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Q.; Zeng, W.; Yu, B.; Gan, J.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, X. Does an Apple a Day Keep Away Diseases? Evidence and Mechanism of Action. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4926–4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Gong, J.; Wang, M. Phloretin and Its Methylglyoxal Adduct: Implications against Advanced Glycation End Products-Induced Inflammation in Endothelial Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 129, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.A.; Polagruto, J.A.; Valacchi, G.; Phung, A.; Soucek, K.; Keen, C.L.; Gershwin, M.E. Effect of Apple Extracts on NF-kappaB Activation in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006, 231, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.-M.; Huang, D.-Y.; Huang, Y.-P.; Hsu, S.-H.; Kang, L.-Y.; Shen, C.-M.; Lin, W.-W. Methylglyoxal Induces Cell Death through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Associated ROS Production and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016, 20, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Parveen, A.; Do, M.H.; Kang, M.C.; Yumnam, S.; Kim, S.Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Methylglyoxal-Induced Aor-tic Endothelial Dysfunction in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liccardo, M.; Perrone, P.; Perrella, S.; Sirangelo, I.; D’Angelo, S.; Iannuzzi, C. Annurca Apple By-Products at Different Ripening Stages Inhibit AGE Formation and Protect Against AGE-Induced Cytotoxicity Through Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020200

Liccardo M, Perrone P, Perrella S, Sirangelo I, D’Angelo S, Iannuzzi C. Annurca Apple By-Products at Different Ripening Stages Inhibit AGE Formation and Protect Against AGE-Induced Cytotoxicity Through Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(2):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020200

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiccardo, Maria, Pasquale Perrone, Shana Perrella, Ivana Sirangelo, Stefania D’Angelo, and Clara Iannuzzi. 2026. "Annurca Apple By-Products at Different Ripening Stages Inhibit AGE Formation and Protect Against AGE-Induced Cytotoxicity Through Antioxidant Activity" Antioxidants 15, no. 2: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020200

APA StyleLiccardo, M., Perrone, P., Perrella, S., Sirangelo, I., D’Angelo, S., & Iannuzzi, C. (2026). Annurca Apple By-Products at Different Ripening Stages Inhibit AGE Formation and Protect Against AGE-Induced Cytotoxicity Through Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants, 15(2), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020200