NADPH Oxidase 1 Mediates Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension in a Murine Model of Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Availability

2.2. Animal Studies

2.3. Metabolic Phenotyping

2.4. Gene Expression

2.5. Pressure Myography

2.6. Blood Pressure Telemetry

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

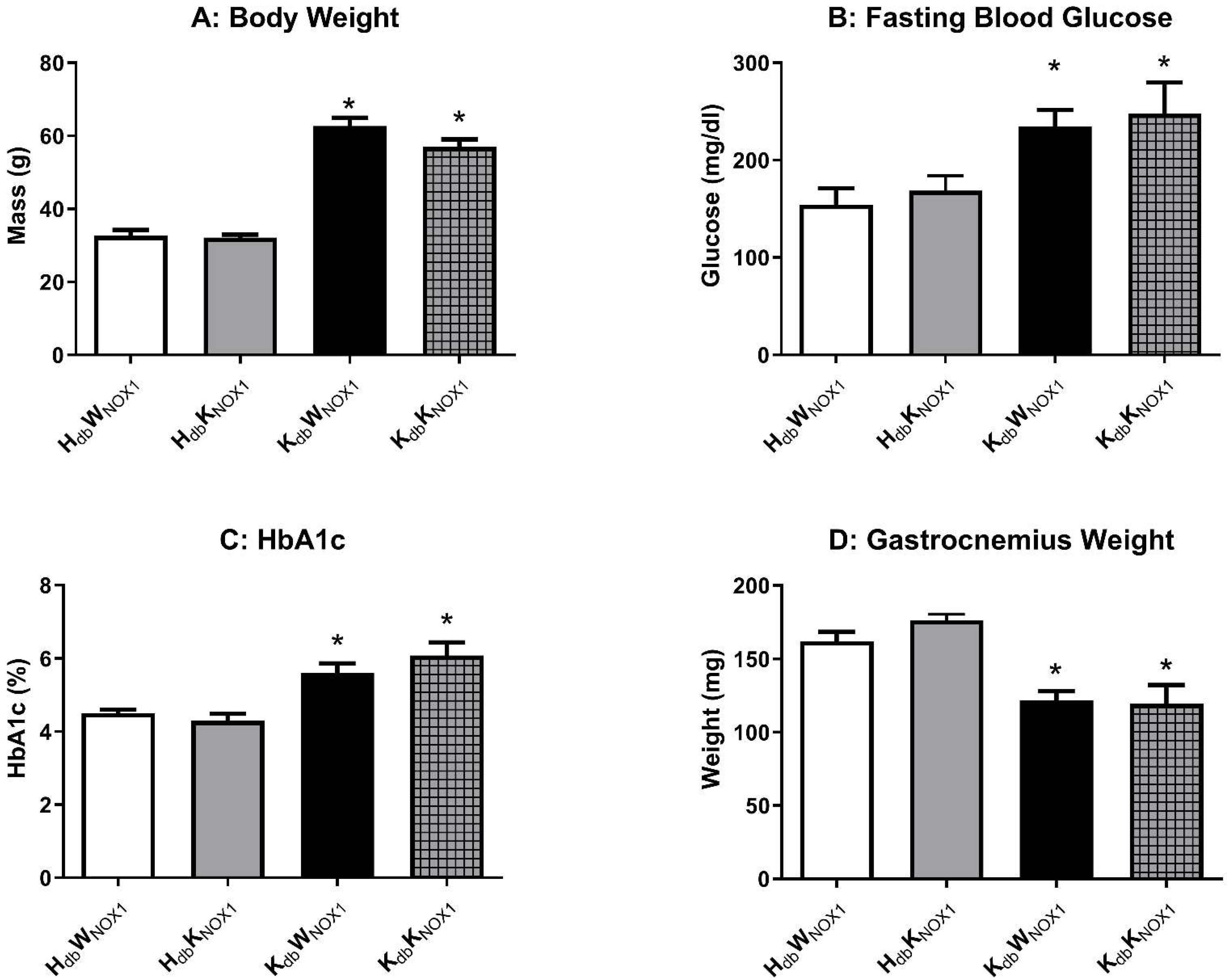

3.1. Obesity-Induced Metabolic Derangement Persists Despite NOX1 Deletion

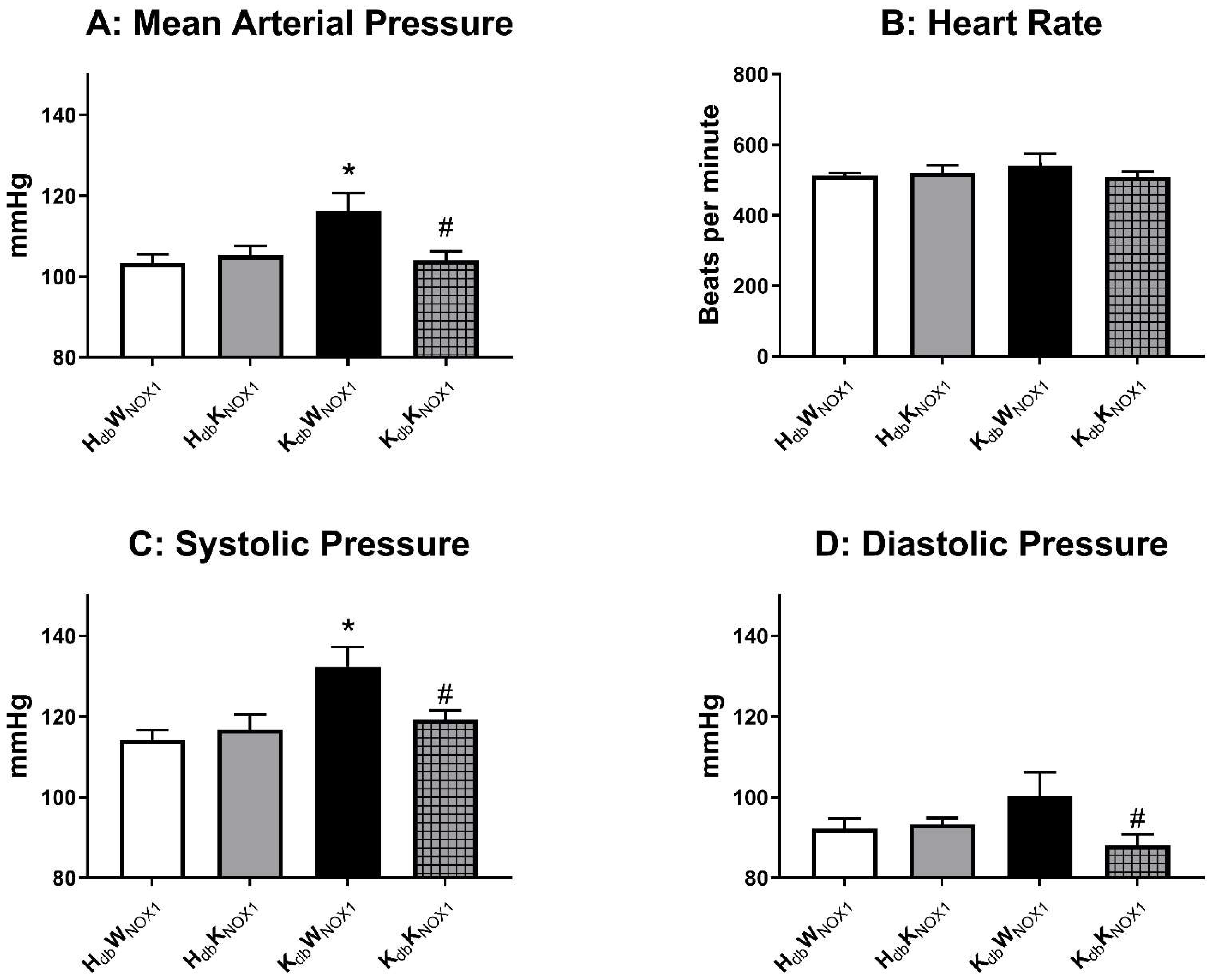

3.2. NOX1 Deletion Abrogates Obesity-Induced Hypertension

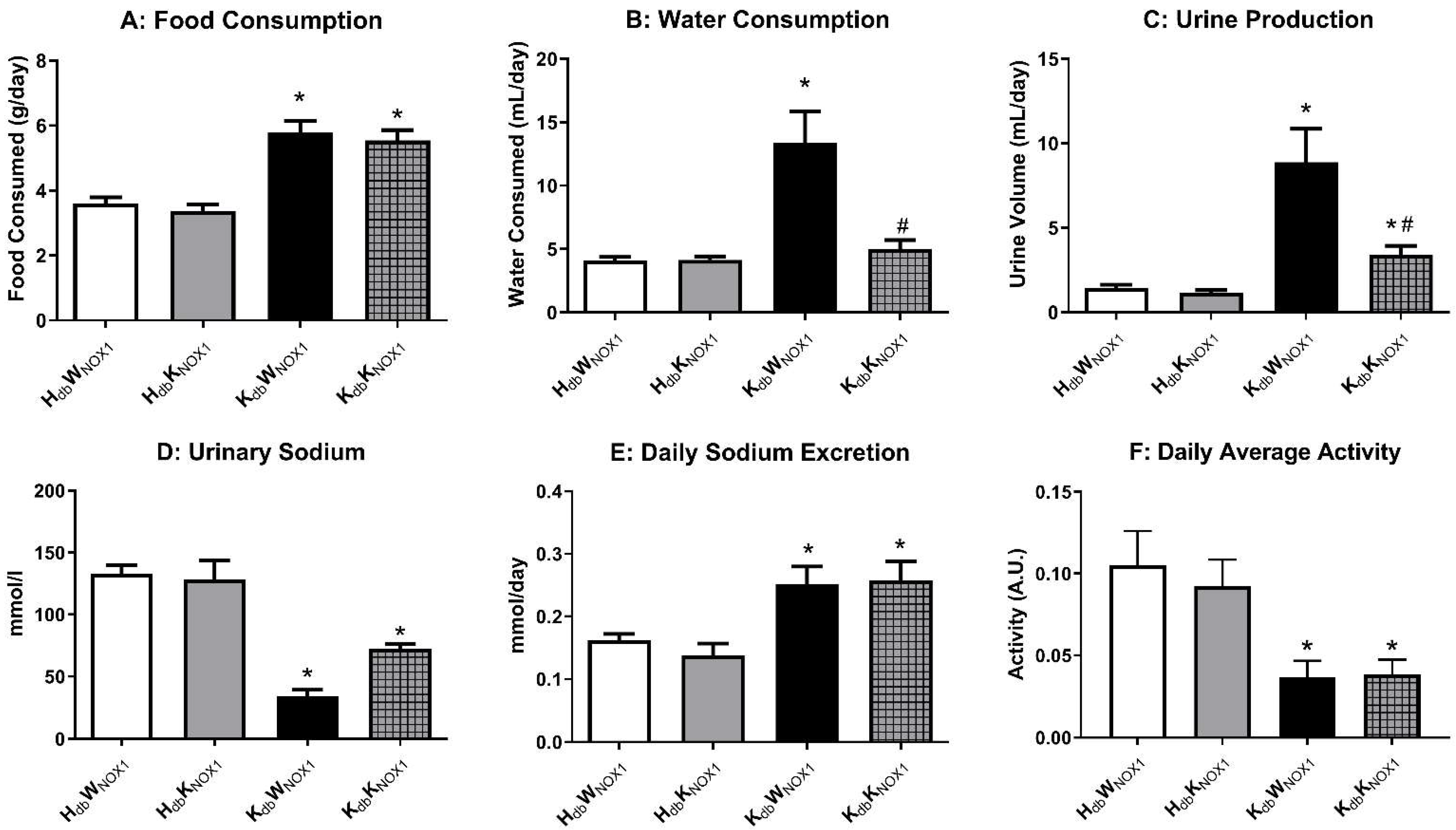

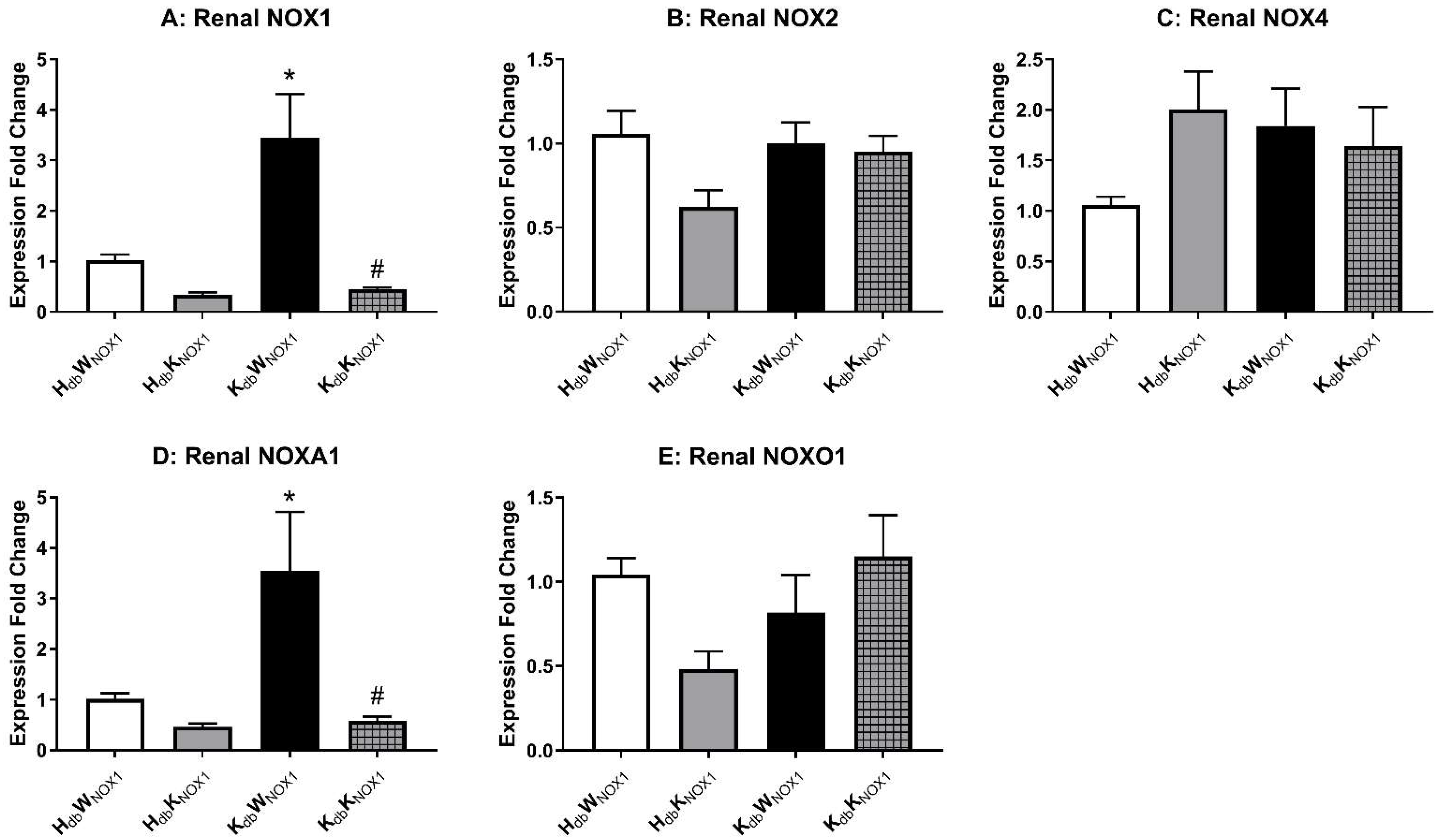

3.3. NOX1 Deletion Improves Renal Function in Obesity

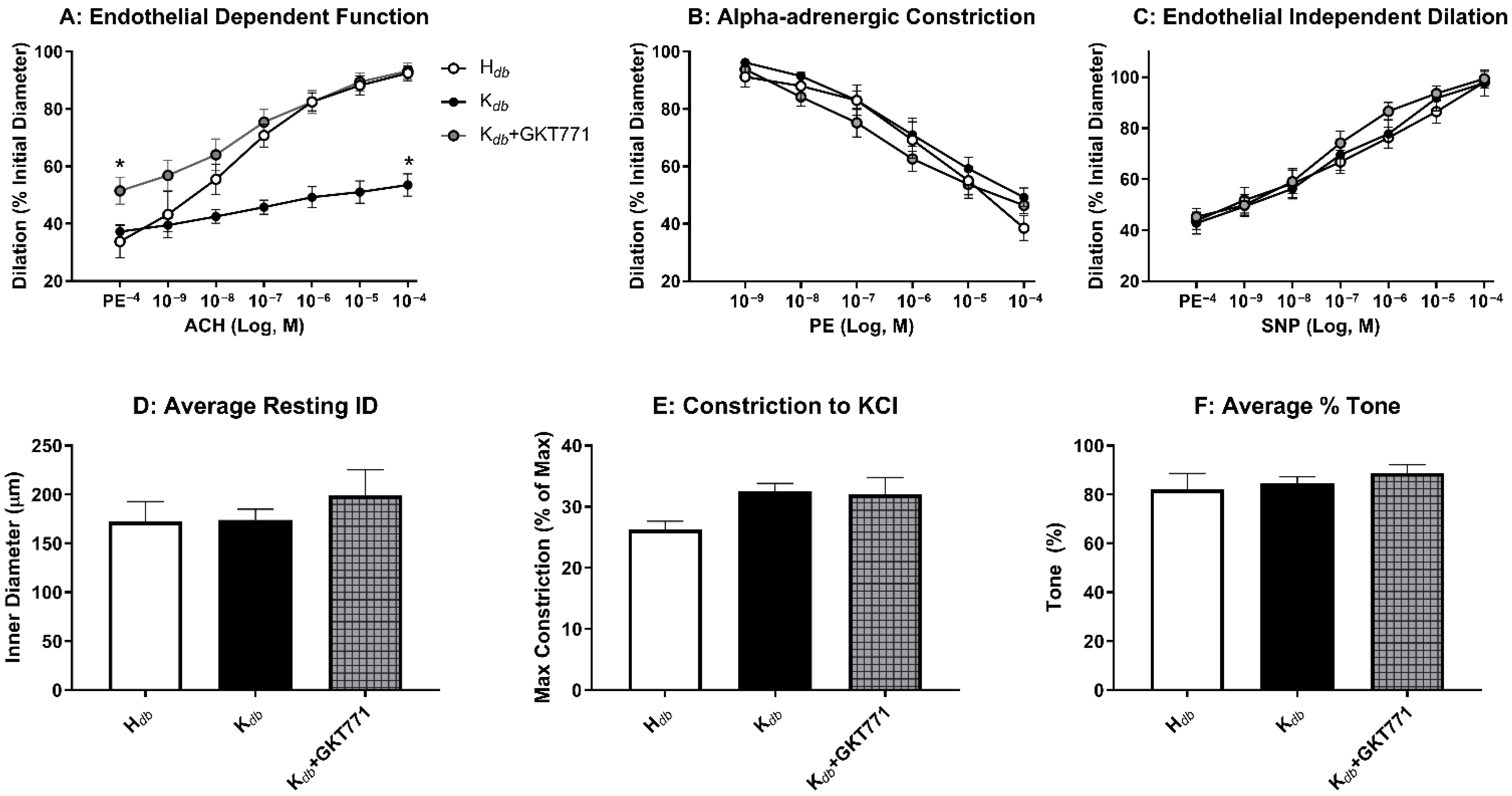

3.4. Pharmacologic Inhibition of NOX1 Rescues Microvascular Endothelial Function

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cawley, J.; Biener, A.; Meyerhoefer, C.; Ding, Y.; Zvenyach, T.; Smolarz, B.G.; Ramasamy, A. Direct medical costs of obesity in the United States and the most populous states. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2021, 27, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Emmerich, S.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Stierman, B.; Ogden, C.L. Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. NCHS Data Brief 2024, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manna, P.; Jain, S.K. Obesity, Oxidative Stress, Adipose Tissue Dysfunction, and the Associated Health Risks: Causes and Therapeutic Strategies. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2015, 13, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Xia, N. The Interplay Between Adipose Tissue and Vasculature: Role of Oxidative Stress in Obesity. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 650214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nunan, E.; Wright, C.L.; Semola, O.A.; Subramanian, M.; Balasubramanian, P.; Lovern, P.C.; Fancher, I.S.; Butcher, J.T. Obesity as a premature aging phenotype—Implications for sarcopenic obesity. Geroscience 2022, 44, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Muñoz, M.; López-Oliva, M.E.; Rodríguez, C.; Martínez, M.P.; Sáenz-Medina, J.; Sánchez, A.; Climent, B.; Benedito, S.; García-Sacristán, A.; Rivera, L.; et al. Differential contribution of Nox1, Nox2 and Nox4 to kidney vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in obesity. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thompson, J.A.; Larion, S.; Mintz, J.D.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J.; Fulton, D.J.; Stepp, D.W. Genetic Deletion of NADPH Oxidase 1 Rescues Microvascular Function in Mice With Metabolic Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Didion, S.P.; Ryan, M.J.; Didion, L.A.; Fegan, P.E.; Sigmund, C.D.; Faraci, F.M. Increased superoxide and vascular dysfunction in CuZnSOD-deficient mice. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Loo, B.; Labugger, R.; Skepper, J.N.; Bachschmid, M.; Kilo, J.; Powell, J.M.; Palacios-Callender, M.; Erusalimsky, J.D.; Quaschning, T.; Malinski, T.; et al. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1731–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pacher, P.; Szabó, C. Role of peroxynitrite in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular complications of diabetes. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 136–141, Erratum in: Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gallo, G.; Volpe, M.; Savoia, C. Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertension: Current Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 798958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Padgett, C.A.; Bátori, R.K.; Speese, A.C.; Rosewater, C.L.; Bush, W.B.; Derella, C.C.; Haigh, S.B.; Sellers, H.G.; Corley, Z.L.; West, M.A.; et al. Galectin-3 Mediates Vascular Dysfunction in Obesity by Regulating NADPH Oxidase 1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, e381–e395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pecchillo Cimmino, T.; Ammendola, R.; Cattaneo, F.; Esposito, G. NOX Dependent ROS Generation and Cell Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santillo, M.; Colantuoni, A.; Mondola, P.; Guida, B.; Damiano, S. NOX signaling in molecular cardiovascular mechanisms involved in the blood pressure homeostasis. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sirker, A.; Zhang, M.; Shah, A.M. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular disease: Insights from in vivo models and clinical studies. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2011, 106, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schröder, K.; Zhang, M.; Benkhoff, S.; Mieth, A.; Pliquett, R.; Kosowski, J.; Kruse, C.; Luedike, P.; Michaelis, U.R.; Weissmann, N.; et al. Nox4 is a protective reactive oxygen species generating vascular NADPH oxidase. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmcke, I.; Heumüller, S.; Tikkanen, R.; Schröder, K.; Brandes, R.P. Identification of structural elements in Nox1 and Nox4 controlling localization and activity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Rittinger, K. Regulation of NOXO1 activity through reversible interactions with p22 and NOXA1. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manea, S.A.; Antonescu, M.L.; Fenyo, I.M.; Raicu, M.; Simionescu, M.; Manea, A. Epigenetic regulation of vascular NADPH oxidase expression and reactive oxygen species production by histone deacetylase-dependent mechanisms in experimental diabetes. Redox Biol. 2018, 16, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Savini, I.; Catani, M.V.; Evangelista, D.; Gasperi, V.; Avigliano, L. Obesity-associated oxidative stress: Strategies finalized to improve redox state. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10497–10538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brand, M.D. Riding the tiger—Physiological and pathological effects of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generated in the mitochondrial matrix. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 55, 592–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thannickal, V.J.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Szyndralewiez, C.; Török, N.J. Pre-clinical evidence of a dual NADPH oxidase 1/4 inhibitor (setanaxib) in liver, kidney and lung fibrosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Streeter, J.; Thiel, W.; Brieger, K.; Miller, F.J., Jr. Opportunity nox: The future of NADPH oxidases as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2013, 31, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, V.T.; Elbatreek, M.H.; Altenhöfer, S.; Casas, A.I.; Pachado, M.P.; Neullens, C.T.; Knaus, U.G.; Schmidt, H.H.H.W. Isoform-selective NADPH oxidase inhibitor panel for pharmacological target validation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 148, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalin, J.; Garrido-Urbani, S.; Heitz, F.; Szyndralewiez, C.; Jemelin, S.; Coquoz, O.; Ruegg, C.; Imhof, B.A. Inhibition of host NOX1 blocks tumor growth and enhances checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201800265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Butcher, J.T.; Ali, M.I.; Ma, M.W.; McCarthy, C.G.; Islam, B.N.; Fox, L.G.; Mintz, J.D.; Larion, S.; Fulton, D.J.; Stepp, D.W. Effect of myostatin deletion on cardiac and microvascular function. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Padgett, C.A.; Butcher, J.T.; Haigh, S.B.; Speese, A.C.; Corley, Z.L.; Rosewater, C.L.; Sellers, H.G.; Larion, S.; Mintz, J.D.; Fulton, D.J.R.; et al. Obesity Induces Disruption of Microvascular Endothelial Circadian Rhythm. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 887559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Larion, S.; Padgett, C.A.; Mintz, J.D.; Thompson, J.A.; Butcher, J.T.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J.; Haigh, S.; Khurana, S.; Fulton, D.J.; Stepp, D.W. NADPH oxidase 1 promotes hepatic steatosis in obese mice and is abrogated by augmented skeletal muscle mass. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2024, 326, G264–G273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sheehan, A.L.; Carrell, S.; Johnson, B.; Stanic, B.; Banfi, B.; Miller, F.J., Jr. Role for Nox1 NADPH oxidase in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2011, 216, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iwata, K.; Ikami, K.; Matsuno, K.; Yamashita, T.; Shiba, D.; Ibi, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Katsuyama, M.; Cui, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. Deficiency of NOX1/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced form oxidase leads to pulmonary vascular remodeling. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Kakehi, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Iwata, K.; Ibi, M.; Ohshima, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Wen, X.; Taye, A.; et al. NADPH oxidase NOX1 is involved in activation of protein kinase C and premature senescence in early stage diabetic kidney. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 83, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorin, Y.; Cavaglieri, R.C.; Khazim, K.; Lee, D.Y.; Bruno, F.; Thakur, S.; Fanti, P.; Szyndralewiez, C.; Barnes, J.L.; Block, K.; et al. Targeting NADPH oxidase with a novel dual Nox1/Nox4 inhibitor attenuates renal pathology in type 1 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2015, 308, F1276–F1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cipriano, A.; Viviano, M.; Feoli, A.; Milite, C.; Sarno, G.; Castellano, S.; Sbardella, G. NADPH Oxidases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Current Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 11632–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liang, S.; Ma, H.Y.; Zhong, Z.; Dhar, D.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Koyama, Y.; Nishio, T.; Karin, D.; Karin, G.; et al. NADPH Oxidase 1 in Liver Macrophages Promotes Inflammation and Tumor Development in Mice. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1156–1172.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, H.; Jiang, T.; Ding, M.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, W.; Ou, H. Nox1/PAK1 is required for angiotensin II-induced vascular inflammation and abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Redox Biol. 2025, 79, 103477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, J.M.; Do, V.Q.; Seo, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Nam, J.H.; Yin, M.Z.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.J.; Griendling, K.K.; Lee, M.Y. NADPH Oxidase 1 Mediates Acute Blood Pressure Response to Angiotensin II by Contributing to Calcium Influx in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, e117–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuno, K.; Yamada, H.; Iwata, K.; Jin, D.; Katsuyama, M.; Matsuki, M.; Takai, S.; Yamanishi, K.; Miyazaki, M.; Matsubara, H.; et al. Nox1 is involved in angiotensin II-mediated hypertension: A study in Nox1-deficient mice. Circulation 2005, 112, 2677–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versari, D.; Daghini, E.; Virdis, A.; Ghiadoni, L.; Taddei, S. Endothelial dysfunction as a target for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, S314–S321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| HdbWNOX | HdbKNOX | KdbWNOX | KdbKNOX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 43 ± 3 | 39 ± 4 | 209 ± 13 * | 207 ± 13 * |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 27 ± 1.5 | 28 ± 4 | 104 ± 5 * | 119 ± 10 * |

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.001 | 2.7 ± 0.3 * | 1.9 ± 0.03 * |

| NEFA (mEq/mL) | 1.5 ± 0.04 | 1.68 ± 0.07 | 5.7 ± 0.2 * | 5.2 ± 0.3 * |

| TNF-a (pg/mL) | 58 ± 5 | 64 ± 5 | 119 ± 17 * | 98 ± 10 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Padgett, C.A.; Butcher, J.T.; Larion, S.; Mintz, J.D.; Fulton, D.J.R.; Stepp, D.W. NADPH Oxidase 1 Mediates Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension in a Murine Model of Obesity. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010060

Padgett CA, Butcher JT, Larion S, Mintz JD, Fulton DJR, Stepp DW. NADPH Oxidase 1 Mediates Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension in a Murine Model of Obesity. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010060

Chicago/Turabian StylePadgett, Caleb A., Joshua T. Butcher, Sebastian Larion, James D. Mintz, David J. R. Fulton, and David W. Stepp. 2026. "NADPH Oxidase 1 Mediates Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension in a Murine Model of Obesity" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010060

APA StylePadgett, C. A., Butcher, J. T., Larion, S., Mintz, J. D., Fulton, D. J. R., & Stepp, D. W. (2026). NADPH Oxidase 1 Mediates Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension in a Murine Model of Obesity. Antioxidants, 15(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010060